FIFTEEN

Central Asia after the Mongols

153

THE SHÏBĀNIDS (SHAYBĀNIDS) OR ABU ‘L-KHAYRIDS

906–1007/1500–99

Transoxania and northern Afghanistan

| c. 842–72/c. 1438–68 | Abu ’l-Khayr b. Dawlat Shaykh b. Ibraāhīm, khān at Tura (Tiumen) in Western Siberia, then ruler also in northern Khwārazm |

| ⊘ 906/1500 | Muḥammad Shïbānī b. Shāh Budaq b. Abi’l-Khayr, Abu ’1-Fath, Shāh Beg Özbeg, conqueror of Transoxania, k. 916/1510 |

| ⊘ 918/1512 | Köchkunju Muḥammad b. Abi ’l-Khayr |

| ⊘ 937/1531 | Abū Sa‘īd b. Köchkunju, Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 940/1534 | ‘Ubaydallāh b. Maḥmūd b. Shāh Budaq, Abu ’1-Ghāzī |

| ⊘ 946/1539 | ‘Abdallāh I b. Köchkunju |

| ⊘ 947/1540 | ‘Abd al-Laṭif b. Köchkunju |

| ⊘ 959/1552 | Nawrūz Ahmad or Baraq b. Sunjuq b. Abi ’l-Khayr |

| ⊘ 963/1556 | Pīr Muḥammad I b. Jānī Beg, great-grandson of Abu ’l-Khayr |

| ⊘ 968/1561 | Iskandar b. Jānī Beg |

| ⊘ 991/1583 | ‘Abdallāh II b. Iskandar |

| ⊘ 1006/1598 | ‘Abd al-Mu’min b. ‘Abdallāh II |

| ⊘ 1006–7/1598–9 | Pīr Muḥammad II b. Sulaymān b. Jānī Beg |

| 1007/1599 | Succession in Bukhārā of the Toqay Temürids or Janīds, descendants of the Khāns of Astrakhan |

When Toqtamïsh and his White Horde moved westwards and united with the Golden Horde in South Russia, Western Siberia fell to the descendants of Jochi’s youngest son Shïban. Later, these descendants came to be known as the Shïbānids (Arabised, perhaps with a hope of suggesting a fictitious connection with the ancient Arab tribe of Shaybān of Bakr, as Shaybānids). One branch of them remained in Siberia as Khāns of Tura or Türnen (Tiumen) until extinguished in the late sixteenth century, but much of the Horde of Shïban moved into Transoxania, where its members acquired the name of Özbegs (presumably after the famous Golden Horde Khan Muhammad Özbeg, 713–42/1313–41, see above, no. 134), becoming the progenitors of the greater part of the indigenous inhabitants of the present-day Uzbek Republic.

Abu ’l-Khayr took over northern Khwārazm and unsuccessfully attacked the Tīmūrids (see above, no. 144) in Transoxania, but his grandson Muhammad conquered Transoxania by 906/1500 from the last Tīmūrids and temporarily occupied Khurasan also. This last was retaken by Shāh Ismā‘īl Ṣafawī (see above, no. 148), but for much of the sixteenth century the Sunnī orthodox Shïbānids carried on warfare against the Shī‘ī Ṣafawids of Persia, and their alliance was courted by other Sunnī empires such as those of the Ottomans and the Mughals of India. The Shïbānid khanate in fact formed a loose family confederacy, with powerful appanages granted out by the ruling supreme khān to various junior members. These appanages were centred upon Balkh, Bukhara, Tashkent and Samarkand, and these local centres became the capital of the whole khanate when their holders moved up and became recognised as supreme ruler.

Abu ’1-Khayrid power reached its peak under ‘Abdallāh II b. Iskandar, effective ruler for nearly forty years, under whom Transoxania experienced much cultural and commercial progress. This Shïbānid clan ruled until 1007/1599, when its last member, Pīr Muḥammad II, was killed by his rival for control of Transoxania, Bāqī Muḥammad b. Jāni Muḥammad, a descendant of Jochi’s son Orda and a connection of the Shïbānids in the female line. The family of Bāqī Muḥammad, the Toqay Temürids or Jānids, then assumed power in Bukhara (see below, no. 154).

However, a collateral line of Shïbānids, the ‘Arabshāhids, ruled in Khwārazm during this period. These were the descendants of ‘Arabshāh b. Pūlād, Pūlād being the great-grandfather of Abu ’1-Khayr. One of them, Ilbars b. Büreke, became khān at Ürgench in 917/1511. The ‘Arabshāhids soon controlled the whole of Khwārazm as far south as northern Khurasan. In c. 1008/c. 1600 the khāns moved their capital to Khiva (Khīwa), and thus there began the khanate of that name which was to endure until the early twentieth century; the ‘Arabshāhid line itself seems to have ended around the end of the seventeenth or the beginning of the eighteenth century.

Lane-Poole, 238–40, 270–3; Zambaur, 270–1, 274–5; Album, 62–3.

EI1 ‘Shaibānī Khān’ (W. Barthold), EI2 ‘Shïbānids’ (R. D. McChesney); EIr ‘‘Arabšāhf (Y. Bregel), ‘Central Asia. VI. In the 10th–l2th/16th–l8th centuries’ (RobertD. McChesney), with a genealogical table of the Abu ’1-Khayrids.

W. Barthold, Histoire des Tures d’Asie Centrale, Paris 1945, 184–8.

N. M. Lowick, ‘Shaybānid silver coins’, NC, 7th series, 6 (1966), 251–330, with a genealogical table and a list of rulers at pp. 255–6.

154

THE TOQAY TEMÜRIDS OR JĀNIDS OR ASHTARKHĀNIDS

1007–1160/1599–1747

Transoxania and northern Afghanistan

| ⊘ 1007/1599 | Jānī Muḥammad b. Yār Muḥammad |

| ⊘ 1012/1603 | Bāqī Muḥammad b. Jānī Muḥammad |

| ⊘ 1014/1605 | Walī Muḥammad b. Jānī Muḥammad |

| ⊘ 1020/1611 | Imām Qulī b. Dīn Muḥammad b. Jānī Muḥammad as Great Khān in Transoxania, with Nadhr Muḥammad b. Dīn Muḥammad as lesser Khān in Balkh |

| 1055–61/1645–51 | Nadhr Muḥammad, as ruler of the reunited khanate, then in Balkh only |

| 1061/1651 | ‘Abd al-‘Azīz b. Nadhr Muḥammad, Khān in Transoxania only, after Great Khān, with Ṣubḥān Qulī b. Nadhr Muḥammad as lesser Khān in Balkh |

| 1092/1681 | Ṣubḥān Qulī as ruler of the reunited khanate |

| 1114/1702 | ‘Ubaydallāh b. Ṣubhān Quli |

| ⊘ 1123–60/1711–47 | Abu ’1-Fayḍ b. Ṣubḥān Qulī |

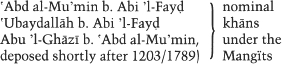

| 1160/1747 | De facto transfer of power to the Mangïts |

| (1160–c. 1163/ | |

| 1747–c. 1750 |

|

| 1164–5/1751–2 | |

⊘ after 1172/1758 |

|

It was a Toqay Temürid force which killed the last Abu ’1-Khayrid Pīr Muḥammad (see above, no. 153). This group, under the leadership of Jānī Muḥammad, descendant of a prince from the ruling house of Astrakhan (see above, no. 131) (whence the name of Ashtarkhānids given to the family which was now to rule in Transoxania and the lands along the upper Oxus), then assumed the khanate for itself, with the general acquiescence of the Özbeg amīrs of Transoxania and Balkh, who regarded its members as being suitable continuers of the Chingizid system. Members of the Jānī Begid family of the Abu’l-Khayrids were elbowed aside. As in previous régimes, appanages were distributed to princes of the new ruling family; but for two considerable stretches during the seventeenth century, there was something like a double khanate system, with one brother in Transoxania as Great Khān and another brother in Balkh as lesser Khān. The Khāns in Bukhara had to preserve their authority against internal elements such as the Qazaqs and external powers like the ‘Arabshāhids of Khwārazm (see above, no. 153), activist and aggressive in the mid-seventeenth century under Abu ’1-Ghāzī and his son Anūsha Muḥammad, while those in Balkh were involved in relations with the Ṣafawids and the Mughals.

Latterly, the rise of powerful Özbeg chiefs and the ravages of the Qazaqs led to a serious decline in order and prosperity in Transoxania. After the death of the last powerful and significant Jānid ruler, Ṣubḥān Qulī, real political power at Bukhara fell more and more into the hands of the Khāns’ Atalïq or Chief Minister Muḥammad Ḥakim Biy Mangït and his son, and it was from the Mangïts that the ultimate line of Khāns of Bukhara was to arise (see below, no. 155). But at least two puppet khāns from the Jānid family were retained by the Mangïts after Abu ’1-Fayd b. Subḥān Qulī’s time (sc. after 1160/1747), and such fainéants seem to have continued on the throne at Bukhara until almost the end of the eighteenth century.

Lane-Poole, 274–5; Zambaur, 273; Album, 63.

EI2 ‘Djānids’ (B. Spuler); EIr ‘Central Asia. VI. In the 10th–l2th/16th–18th centuries’ (Robert D. McChesney). ‘VII. In the 12th–13th/18th–19th centuries’ (Y. Bregel).

Hélène Carrére d’Encausse, Islam and the Russian Empire. Reform and Revolution in Central Asia, London 1988, with a list of the rulers in Bukhara at p. 193.

1166–1339/1753–1920

The Khanate of Bukhara

| 1160/1747 | Muḥammad Raḥīm Atalïq b. Muḥammad Ḥakim Biy, at first with puppet khāns, after 1166/1753 as sole ruler and Amīr, in 1170/1756 Khān |

| ⊘ 1172/1758 | Dāniyāl Biy Atalïq b. Muḥammad, uncle of Muḥammad Raḥīm, at first as regent for his nephew Fāḍil Tora, then with puppet Jānid khāns |

| ⊘ 1199/1785 | Shāh Murād b. Dāniyāl Biy, Amīr-i Ma‘ṣūm |

| ⊘ 1215/1800 | Sayyid Ḥaydar Tora b. Shāh Murād |

| ⊘ 1242/1826 | Sayyid Ḥusayn b. Ḥaydar Tora |

| 1242/1827 | ‘Urnar b. Ḥaydar Tora |

| ⊘ 1242/1827 | Naṣr Allāh b. Ḥaydar Tora |

| ⊘ 1277/1860 | Muẓaffar al-Dīn b. Naṣr Allāh |

| ⊘ 1303/1886 | ‘Abd al-Aḥad b. Muẓaffar al-Dīn |

| ⊘ 1328–39/1910–20 | Sayyid ‘Ālim Khān b. ‘Abd al-Ahad |

| 1339/1920 | Overthrow of the Khānate |

The Mangïts of Bukhara arose from an Özbeg tribe of the same name which became influential under the Toqay Temürids or Jānids (see above, no. 154), so that in the early eighteenth century Khudāyār Biy Mangït became Atalïq or Chief Minister to Abu ’1-Fayḍ Khān, being followed in this office by his son Muḥammad Ḥakīm and his grandson Muḥammad Raḥīm. Very soon the family became the real rulers in Bukhara, although they continued to enthrone puppet khāns from the Jānids until the end of the eighteenth century. Shāh Murād, however, ended this pretence and himself reigned as fully sovereign Amīr; this last title was borne by all the remaining members of his line, indicating that they saw themselves as Islamic monarchs par excellence and not as khāns in the Turkish steppe tradition.

The greatest single event in the history of Central Asia during the nineteenth century was, of course, the territorial and military advance of Imperial Russia. The Amīr Muẓaffar al-Dīn was crushingly defeated by the Russians, lost some of his territory and in effect lost his independence (1285/1868). The Khanate survived, within somewhat shrunken boundaries, with little Russian interference in its internal affairs, so that the Amīrs remained as despotic and capricious and the religious classes as fanatical and ignorant as before. But in September 1920 the Amīr’s rule was overthrown and a ‘People’s Republic of Bukhara’ set up, soon to be replaced by a forcibly imposed Bolshevism; the last ruler, ‘Ālim Khān, fled to exile in Kabul.

Lane-Poole, 276–7; Zambaur, 273–4; Album, 63.

EI2 ‘Mangits’ (Y. Bregel); EIR ‘Central Asia. VII. In the 12th–13th/18th–19th centuries’ (Yuri Bregel).

Hélène Carrère d’Encausse, Islam and the Russian Empire, with a list of rulers at p. 193. Edward A. Allworth, Central Asia: 130 Years of Russian Dominance, 3rd edn, Durham NC and London.

1184–1338/1770–1920

The Khanate of Khiva (Khiwa)

| 1184/1770 | Muḥammad Amīn as Ïnaq for puppet khāns of the Qazaq Chingizids |

| 1204/1790 | ‘Awaẓ b. Muḥammad Amīn, Ïnaq |

| 1218/1803 | Eltüzer b. ‘Awaẓ, Inaq and then in 1219/1804 Khān |

| ⊘ 1221/1806 | Muḥammad Raḥīm b. ‘Awaẓ |

| ⊘ 1240/1825 | Allāh Qulī b. Muḥammad Raḥim |

| 1258/1842 | Raḥīm Qulī b. Allāh Qulī |

| ⊘ 1261/1845 | Muḥammad Amīn b. Allāh Qulī, Abu ‘l-Ghāzi, called Medemīn |

| 1271/1855 | ‘Abdallāh b. ‘Ubaydallāh, great-grandson of ‘Awaẓ |

| 1272/1856 | Qutlugh Murād b. ‘Ubaydallāh |

| ⊘ 1272/1856 | Sayyid Muḥammad Bahādur b. Muḥammad Raḥīm |

| ⊘ 1281/1864 | Sayyid Muḥammad Raḥīm b. Sayyid Muḥammad Bahādur |

| 1328/1910 | Isfandiyār b. Sayyid Muḥammad Raḥīm |

| ⊘ 1336–8/1918–20 | Sa‘īd‘Abdallāh |

| 1338/1920 | Overthrow of the Khanate |

By the mid-eighteenth century, power in the Khānate of Khiva, covering essentially the older province of Khwārazm, was disputed by two powerful families of the Qazaq Chingizids. In 1176/1763, the leader of the Qungrat tribe of the Özbegs, Muḥammad Amīn Ïnaq (the old title ïnaq ‘trusted adviser [of the ruler]’ was by now given to tribal chiefs), became chief of all the local Özbeg tribal chiefs. As Atalïq of Khiva, he subdued the Yomud Turkmens and became virtual ruler, installing puppet khāns from the Qazaq Chingizids. He and his son ‘Awaẓ nevertheless did not themselves assume the title of Khān, but Eltüzer b. ‘Awaẓ felt strong enough to dispense with Chingizid puppets and proclaim himself Khān, founding a new, and the ultimate, line of rulers in Khiva. As in the other two Central Asian khanates, the rulers were by now able to behave more despotically through a declining reliance on Özbeg and other tribal forces and the use of their own personal forces of guards. The Khāns of Khiva were for a while able to expand as far south as Merv (Marw); they continually raided Persian territory in northern Khurasan; and they expanded northwards into the Qazaq Steppe.

But the Khāns were totally unable to withstand Russian pressures. In 1290/1873, a Russian army occupied Khiva with minimal resistance, and stringent peace terms were imposed on what now became a vastly-reduced khanate. The Russians did not interfere internally at Khiva, but the Khāns had no independent status and were far more circumscribed than their fellow-Khāns of Bukhara. In April 1920 the last Khān Sa‘īd ‘Abdallāh was deposed and a ‘People’s Republic of Khiva’ proclaimed, to be replaced a year later by a Bolshevik regime.

Lane-Poole, 278–9; Zambaur, 275–6; Album, 64.

EI2 ‘Khīwa’ (W. Barthold and M. M. Brill), Suppl. ‘na![]() ḳ’ (Y. Bregel); EIR ‘Central Asia. VII. In the 12th–13th/18th–19th centuries’ (Yuri Bregel).

ḳ’ (Y. Bregel); EIR ‘Central Asia. VII. In the 12th–13th/18th–19th centuries’ (Yuri Bregel).

Edward A. Allworth, Central Asia: 130 Years of Russian Dominance, 3rd edn.

1213–93/1798–1876

The Khanate of Khokand (Khoqand)

| 1213/1798 | ‘Ālim b. Nārbūta Biy |

| ⊘ 1225/1810 | Muḥammad ‘Umar b. Nārbūta Biy |

| ⊘ 1238/1822 | Muḥammad ‘Alī b. Nārbūta Biy |

| 1258/1842 | Shīr ‘Alī b. Ḥājjī Biy |

| ⊘ 1261/1845 | Murād b. ‘Ālim |

| 1261/1845 | Muḥammad Khudāyār b. Shīr ‘Alī, first reign |

| ⊘ 1274/1858 | Mallā b. Shīr ‘Alī |

| ⊘ 1278/1862 | Shāh Murād, nephew of Mallā |

| 1278/1862 | Muḥammad Khudāyār, second reign |

| ⊘ 1280/1863 | Sayyid Sulṭān or Sulṭān (Mīr) Sayyid b. Mallā |

| ⊘ 1281/1865 | Muḥammad Khudāyār, third reign |

| 1292–3/1875–6 |

|

| 1293/1876 | Suppression of the Khānate by Russia |

During the later eighteenth century, a third Özbeg khanate, in addition to those of Bukhara and Khiva (see above, nos 155–6), emerged under leaders of the Ming tribe in Farghāna. The rise of the ruling family is usually traced back to Shāh Rukh Atalïq (d. between 1121 and 1133/1709–21). His son ‘Abd al-Karim Biy in 1153/1740 founded the town of Khokand, which was to become the capital of his family’s khanate. His grandson Nārbūta united Farghāna under Ming rule, so that his son and successor ‘Ālim could assume the title of Khān and formally begin the dynasty. His brother and successor Muḥammad ‘Umar went even further and claimed the title of Amīr al-Mu’minīn on his coins. The Mings soon came to control very extensive territories, beginning with the capture of Tashkent, of great strategic and commercial importance, in 1224/1809, and continuing with expansion northwards into the Qazaq Steppe and across the T’ien Shan into Eastern Turkestan, where the Khāns controlled customs duties from the so-called ‘six towns’ there, and into the Pamirs region. Khokand thus became greater in territory than its two fellow-khanates, if not in population.

Like the other khanates, Khokand was racked by internal tribal and other feuds, and was at one point briefly occupied by Bukhara. It was also threatened by Russian imperial expansion. In 1282/1865, Tashkent was captured and a commercial treaty imposed by Russia on Khokand. In 1292/1875, an internal rebellion brought the Russian army into the Khanate, and early in the next year it was suppressed and its territories annexed to the governorate-general of Turkestan as its Farghānan province.

Lane-Poole, 280; Zambaur, 276; Album, 64.

EI2 ‘Khoḳand’ (W. Barthold and C. E. Bosworth); EIR ‘Central Asia. VII. In the 12th–13th/18th–19th centuries’ (Yuri Bregel).

Edward A. Allworth, Central Asia: 120 Years of Russian Rule, 3rd edn.