CHAPTER 5

QUEEN VICTORIA STUDIES TV

Acupuncture is a living and stubborn challenge to established “scientific” knowledge. Its roots are at least four thousand years old, and it is based on a philosophy and view of the body-mind that is entirely different from modern views. It is a total anachronism but it refuses to disappear. If Qi and channels really exist, then modern “scientific” views of the body-mind clearly need to be revised. —GIOVANNI MACIOCIA

Function versus Structure

The natural consequence of the current surge in Eastern medicine is the requirement to pursue modern scientific research into the underlying mechanisms. At first glance, modern scientific basic research into acupuncture would appear to entail seeking an explanation for the workings of the ancient therapy. On closer inspection, however, this pursuit represents a collaborative synthesis between Eastern and Western culture. Modern science and conventional Western medicine were wholly developed in, and based on, Western culture and thinking. As such, this research necessitates attempting to understand a system of medicine derived from Eastern thinking from the viewpoint of Western people and culture.

One of the biggest differences between Eastern and Western culture is that Eastern medicine, in particular acupuncture practice and theory, pays more attention to function than to structure. This inclination stems from a deep-seated principle that as long as a form of medicine works well, it is a good one. Conversely, Western medicine is more focused on structure, based on its entrenched conviction that, in the words of French philosopher René Descartes, “Man is machine”—the human body is merely a complicated machine and medical doctors are engineers. The more the engineers understand the structure of the machine, the better they are able to repair it.

The conviction that the body is a machine provides powerful motivation to disassemble the machine into smaller and smaller parts. Anatomy dissects the human body into various organs, then cellular biology dissects the organs into their various microscopic cells and components, and finally molecular biology dissects cells into their various molecules. As things currently stand, anatomy, cellular biology, and molecular biology have laid down a very solid and reliable structure for modern Western medicine.

If the structure that corresponds to the function of Eastern medicine can be discerned, both Eastern and Western medicine will enjoy a common base. This simple motivation initiated modern scientific basic research into acupuncture after World War II. The journey of discovering the structure that corresponded to the function of acupuncture can be divided into five steps, discussed under the following headings.

Are There Little Puppets inside the TV?

Researching acupuncture is not a simple matter of translating between two languages. The function of acupuncture was not based on the workings of a rationally designed machine, but instead developed entirely from experience and intuitive insight. Difficulties arose when scientists attempted to disassemble “the machine” of the acupuncture system.

Initially, scientists believed they could reveal the mechanics of the acupuncture system as soon as they employed the powerful methods and knowledge systems of anatomy, cellular biology, and molecular biology. Unfortunately, some functions of acupuncture exist beyond the scope of these disciplines, and the research consequently became an extremely difficult task.

To illustrate the early period of this research, from the 1950s to the 1980s, let us explore an analogy where scientists in the time of Queen Victoria attempt to come to terms with the mechanism of television. Suppose the queen was fortunate enough to be given a television set by an alien civilization. Aside from powering itself and tuning to a signal beamed in from the alien home world, this television was identical to those of our everyday experience. It functioned, but the inhabitants of the era, unaware of the concept of electromagnetic fields and waves, did not understand the working principle.

The queen invited a group of prominent scientists to devise a method to investigate the mechanism behind the mysterious playing-box. Their first, very reasonable, supposition would be that there were small puppets acting behind the window of the box. Thus, as soon as they opened the box, they could immediately capture these miniature actors and display them.

The underlying logic of scientists’ suppositions at the onset of modern science’s investigation of acupuncture was almost identical. Initially, many scientists hypothesized that acupuncture meridians might be a kind of pipeline or cable, like a blood vessel or nerve fiber. In this context, the acupuncture point would be a node on the cable, like a nerve node.

In 1963, North Korean biologist Bonghan Kim announced that he had found a new system composed of “Bonghan corpuscles,” which corresponded to acu-points, and “Bonghan ducts,” which corresponded to acu-meridians. Cold War dynamics led to his work being prematurely overpropagated by newspapers and magazines in North Korea and the Soviet nations, establishing him as a national hero. Given the potential contribution to the development of medicine, it was also captivating news among the international scientific community.

According to the criteria of modern science, any experiment has to be reproducible by other scientists under the same conditions. If an experiment is reproducible, it is regarded as a true and reliable result. The importance of this discovery led many scientists in China, Germany, France, Austria, and the United States to repeat his method, but no one else could confirm his discovery.

After carefully repeating Kim’s experiment, noted Austrian histologist Gottfried Kellner wrote a long paper titled “Structure and Function of Skin.” In his opinion, the “Bonghan corpuscle” was actually the end body, the residual stump of a capillary remaining after embryo development. Similarly, the “Bonghan duct” was the corresponding residual capillary. While these are real structures in the skin and other parts of the body, and would react to acupuncture stimulation, they do not possess the function of the acupuncture system. This groundbreaking news became a major scientific scandal that led Kim to commit suicide.

A balanced assessment of the incident would concede that Kim was an important pioneer and a victim of the demanding task of scientifically exploring acupuncture. It is, of course, a sad story, but his mistake served as an important lesson in pursuing this research. Attempting to locate a visible anatomical entity that corresponded to the acupuncture system was natural and logical. Mistakes are common in science, particularly in the exploration of a completely new area. The scandal of Kim’s work was a result of premature and overexuberant reporting.

Are Acupuncturists Swindlers and Their Patients Deranged?

The scandal involving Kim’s research dealt a substantial blow to acupuncture research, steering it into a dark period. Instead of delving into the mechanisms underlying acupuncture, the question became “Does the acupuncture system exist objectively?” Common opinion in the scientific community at the time held that “neither evidence for its efficacy nor a plausible hypothesis for its action can be advanced.”1 This attitude also implied that the theoretical framework of acupuncture was imaginary, the needling procedures based on fantasy, and any effects on patients purely placebo.2 The ultimate implication was that the entire history of acupuncture was one of swindling practitioners and deranged patients.

An example illustrating the attitude of scientists at the time occurred during the First National Conference of Acupuncture in China in 1977. Patients who reported a sensation being propagated along a meridian after being stimulated by needles were required to undergo psychological testing to ensure they were not suffering from a mental disorder. Naturally, this suspicious attitude was insulting to acupuncturists and other traditional Chinese medical practitioners. Patients’ sensations of propagation along meridians are the most important indication used by acupuncturists to judge the effectiveness of a needling operation. It is untenable that countless numbers of patients had been misleading acupuncturists for thousands of years.

In order to prove that the acupuncture system was not a fantasy, a large-scale investigation was organized in China during the 1970s, focusing on the phenomenon of sensation propagation along meridians. The project marked the first time that the reliability of acupuncture theory was assessed from the viewpoint of modern science, and thus from the viewpoint of Western culture and thinking. It is also the largest research project undertaken in China to date, involving twenty-eight institutions and thousands of medical doctors from all over China, even extending to Chinese medical teams in Africa. In a period spanning six years, 63,228 people of varying gender, age, and race were tested.

In the context of acupuncture, “sensation” refers to the feeling patients experience during needling operation. When successfully directed to the correct position, a special sensation occurs that moves slowly along the corresponding meridian. The feeling is usually experienced as something like sourness, swelling, numbness, pain, warmth, coldness, or an electric shock. Occasionally, one of these sensations occurs in isolation, but normally it is experienced as a mixture of sourness, swelling, and numbness. In terms of the ancient theory of acupuncture, these sensations are attributable to Qi.

In some ways, this form of investigation resembles a public opinion poll. However, even though it is related to subjective experience rather than objective measurement, it complies with modern scientific standards. The methodology of the investigation was also fully standardized in accordance with the criteria of modern science. For example, the methodology stipulated the feeling of Qi stimulated by a low-frequency-pulse electronic instrument using a silver electrode of 0.1 to 0.2 inches in diameter. These electrodes were applied to “well-points,” which are on the tops of fingers and toes, or “source-points,” usually on the joints of wrists or ankles. The vast majority of scientists in the project conformed to this standard. However, some used needles or hand pressure to stimulate, and some stimulated other acu-points instead of well-points or source-points.

The degree of sensation and the forms to record results were also standardized to enable statistical analysis. The investigation found that 78 percent of the subjects experienced the feeling of sensation propagation along meridians. Obviously it is difficult to assert that over 40,000 people were all deranged in the same manner. As it is established that a purely placebo effect plays, at most, a role in 25 to 30 percent of cases, the result of 78 percent experiencing sensation propagation far exceeds what could be attributable to that.

Asking the Questions Ancient People Didn’t

The outcomes of this project extended far beyond the original scope, and many investigators took the opportunity to ask a number of questions not asked in ancient times. For two thousand years China was dominated by Confucianism, which served as both the official national religion and a standard of human behavior in society. According to its principles, it was forbidden to question the word of an authority, let alone to criticize or challenge it.

While very effective in preserving the power of large central governments and totalitarian rulers, Confucianism did not facilitate the development of science. The first questions concerning the veracity of acupuncture were asked by Chinese scientists who were educated in Western science and the principles it derives from Western culture. They took the opportunity to look for answers in their observations, allowing them to clarify many vague concepts in acupuncture. This ultimately helped scientists reveal the secrets behind the mysterious acupuncture system.

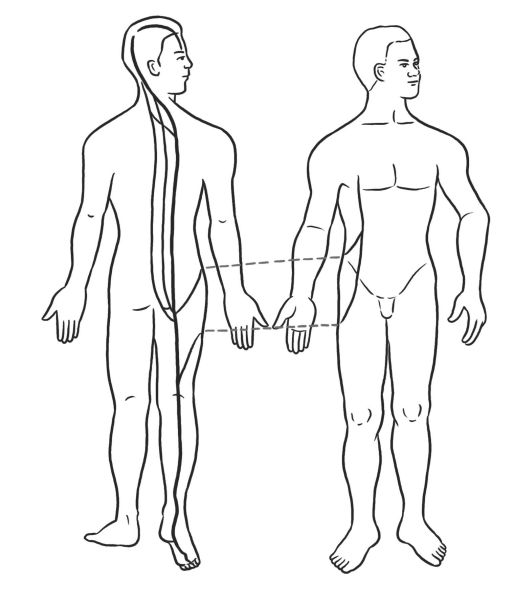

Figure 5.1. Superposition of the routes of sensation propagation along the Bladder Meridian, from one hundred test subjects.

Accuracy of the Ancient Records

One of the questions that were forbidden at colleges of Traditional Chinese Medicine was whether the classical texts contained any errors in their description and teaching of acupuncture. The network of the meridian system is clearly depicted in the ancient texts, and the researchers in the project, unfettered by the strictures of Confucianism, took the opportunity to evaluate their accuracy by comparing the routes of sensation propagation with the locations of meridians stipulated in the texts.

Generally speaking, the routes of sensation propagation and the corresponding meridians in the classic texts coincided closely on the limbs. On the trunk, however, they were somewhat shifted, and the difference on the head was quite significant. The routes of sensation propagation also differed among subjects, although in most cases the difference was minor.

Stability and Flexibility of the Route of Sensation Propagation

Interestingly, when a person is seriously ill, the routes of sensation propagation can be completely altered (fig. 5.2). Instead of the original paths, the sensation propagation usually travels directly to the focus of the disease. This easily observable phenomenon was recorded in the ancient texts and indicates that a meridian is not a fixed channel, like a blood vessel or a nerve fiber, but rather something variable that adapts to one’s physical state. Unfortunately, most scientists searching for the structure of the acupuncture system ignored this important phenomenon.

Figure 5.2. Sensation propagation moves to the location of the focus of disease.

Figure 5.3. Major changes in the routes of sensation propagation.

In rare cases, even larger changes in the path of sensation propagation can be observed (fig. 5.3). Consequently, it is unnecessary to search for a fixed structure that corresponds to the acupuncture meridian network.

Repeat observations, where the same needling operations were performed every day on the same person, were also made during this project. They revealed that, provided experimental conditions are consistent, the routes of sensation propagation are relatively stable, on the order of 86.7 percent, while other cases exhibited 0.4- to 0.8-inch deviations. This implies that the routes of sensation propagation can vary from one day to another, even if the same point is stimulated on the same person.

These observations suggest that the record in the ancient texts is essentially correct, but not perfectly so. Another conclusion that may be inferred is that, contrary to what many once believed or expected, the meridian is not a material entity. These two conclusions were important for the subsequent research into the mechanics of acupuncture.

Width and Depth of the Route of Sensation Propagation

The ancient records of acupuncture contain no information concerning the width and depth of the meridians. In the 1970s research project, however, the width and depth of the route of sensation propagation were observed and recorded.

For most people, the route of sensation propagation is not the thin thread demonstrated in the texts, but rather a band with a central region and a margin (at left in fig. 5.4). The width of the central region is narrow, at 0.08 to 0.2 inches, and is associated with a clear feeling of sensation propagation. The margin is broad, at 0.8 to 2 inches, and is associated with incidents of weaker, vaguer sensation propagation. Another interesting phenomenon is that when the needling location is shifted slightly from the center of the acu-point, the route of sensation propagation also shifts slightly to a parallel position (at right in fig. 5.4).

Figure 5.4. The route of sensation propagation along the Lung Meridian.

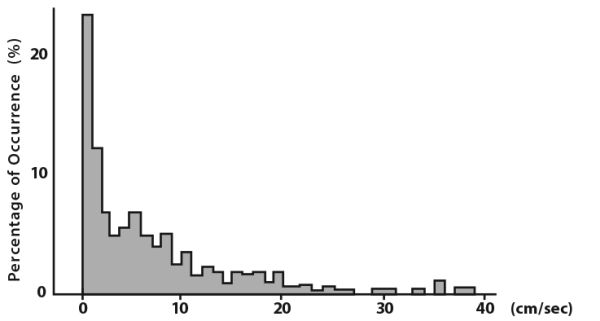

Figure 5.5. Speed distribution of sensation propagation.

Direction and Speed of Sensation Propagation

Unlike blood circulation, sensation propagation usually progresses simultaneously in both directions, proximally (toward the center of the body) and distally (away from the center of the body). At around 0.4 to 8 inches per second (fig. 5.5), the speed of the progression is usually quite slow compared to signals in nerve fibers, which travel at 6 to 400 feet per second. It is worth noting that the speed of signal propagation along meridians later proved to be the key to revealing the mechanism behind the acupuncture system.

Ear-Needling and Sensation Propagation

Many investigators in this research project found that stimulating different acu-points in the ear that corresponded with different meridians could induce several routes of sensation propagation. The sensation propagation initially progresses inside the ear, then across the outer ear and along the related meridian.

Enhancing Sensation Propagation

This project also revealed that sensation propagation could be enhanced by numerous factors: increasing body temperature using a bath; injecting certain drugs such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP), coenzyme A (CoA), and cytochrome c; ingestion of some Chinese herbal remedies; and even meditation.

A Real Event in the Body, or Merely an Illusion in the Brain?

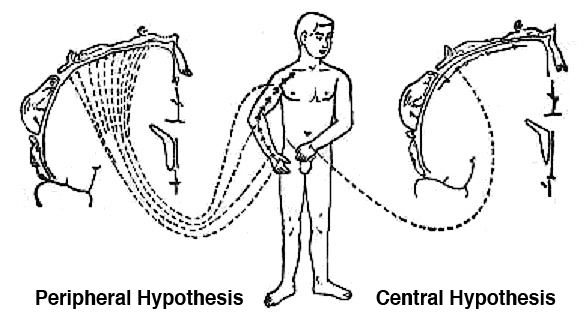

The evident contradiction between the established presence of the function of acupuncture and the absence of a corresponding structure posed a major conundrum for scientists engaged in acupuncture research. The question arose whether the phenomenon of sensation propagation along meridians was a real event in the body or merely an illusory sensation caused by activity in the brain.

Figure 5.6. Competing hypotheses to explain sensation propagation.

There are two major schools of thought in explaining the cause of sensation propagation. These are generally referred to as the central hypothesis and the peripheral hypothesis. The central hypothesis (at right in fig. 5.6) asserts that sensation propagation along meridians exists only in the brain and does not involve the body. On the surface it would appear that the central hypothesis is a variation of the opinion that acupuncture is merely a fairy tale. Adherents concede the objective existence of the acupuncture system but think it is only the activity of the cerebral cortex:

1. The stimulation of an acu-point is transmitted by nerve fiber to a corresponding position in the cerebral cortex.

2. This site in the brain then secretes certain chemical compounds, which diffuse to neighboring locations and trigger a response in those areas.

3. These neighboring locations are connected by nerve fibers to locations on the body that correspond with the route of sensation propagation.

4. Thus, chemical-triggered responses within the brain provide the feeling of sensation propagation.

This is an attractive and elegant hypothesis, and physiologist W. J. S. Krieg produced an impressive diagram to demonstrate it. It divides the skin into twelve regions that are reflected in the cerebral cortex and correspond to the twelve major meridians in the body (fig. 5.7).3

As elegant as it is, the central hypotheses must answer some challenges. For instance, inconsistencies in the relationship between the routes of meridians and their projection in the somatesthetic receptive field of the cerebral cortex must be addressed. It is evident from figure 5.8 that the sensation projection on the somatesthetic receptive field of the cerebral cortex would have to leap over the wide area assigned to feelings from the arm and hand when sensation propagates along any of the three Yang meridians, which run from foot to head.

Figure 5.7. Krieg’s assumed distribution of somatosensory areas corresponding to the somatic cortex.

While numerous cases of sensation propagation can be explained by the mechanism outlined in the central hypothesis, it has more difficulty explaining many other experimental results. These include visible physiological and pathological change along meridians and other measurements outlined below.

On the other hand, there is plenty of experimental evidence to support the peripheral hypothesis (fig. 5.6), which holds that sensation propagation is a process occurring in the body rather than the brain. For example, the correlation between areas of lower resistance and lines of lower resistance on the skin with acu-points and meridians, discovered by Croon and Nakatani, is well established, and is discussed in depth in chapter 6. Vol’s subsequent systematic development of this discovery has seen it widely applied in Germany and other countries since 1953 as a standardized diagnostic method.

Also, since the 1926 invention of Kirlian photography, which captures high voltages and high frequencies, many scientists have employed it to detect acu-points and meridians. Continued improvements in this technique now allow meridians to be clearly demonstrated in a darkened room (fig. 5.9).

Figure 5.8. Comparison of the three Yang meridians of the foot and the somatesthetic receptive field of the cerebral cortex.

Figure 5.9. High-voltage, high-frequency photograph of a meridian.

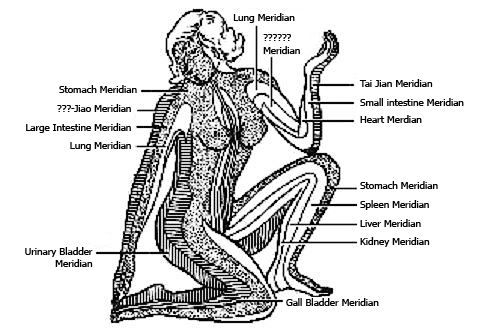

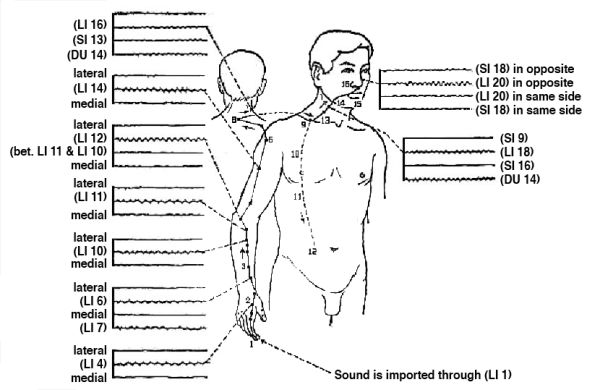

Additionally, doctors and medical practitioners using soft laser therapy in the West have found that the meridians coincide with channels of light. Chinese physicist Bi-wu Zhang found that the meridians appear as channels of microwaves. Various other observations reveal that in addition to appearing as channels of electromagnetic waves, meridians are also a channel for acoustic waves (fig. 5.10).

Figure 5.10. Acoustic signals propagation along meridians.

The phenomenon of areas of lower electrical resistance correlating with acoustic channels is not only observable on human skin but also on the skin of animals and plants (plates 5 and 6 in the color plate section).

Finally, isotope tracing techniques, which involve inserting radioactive isotopes into the body and using the radiation emitted to track their movement through the body, show that meridians are not only a channel for waves but are also the path taken by some chemical components. There is no physical channel in the body that can explain why the isotopes follow these paths. Plate 7 in the color plate section shows an isotope following the Kidney Meridian.

Is There Something Beyond Our Present Knowledge?

The contradiction between acupuncture’s established function, supported by both clinical success and rigorous scientific observation, and the absence of a corresponding structure is a major challenge to scientists. In terms of chapter 1’s analogies, the absence of a physical subject makes the research more difficult than the one facing the blind world’s scientists researching the elephant, but similar to their research into the rainbow. This has led many medical doctors and scientists, particularly physiologists, to employ the “ostrich approach.” When contemplating acupuncture, they consider only those phenomena that are consistent with current physiological understanding and bury their heads in the sand when confronted with phenomena that contradict this understanding.

Some scientists, sensing the opportunity to extend scientific understanding, paid special attention to these contradictory phenomena. To restate the words of Maciocia that opened this chapter, “Acupuncture is a living and stubborn challenge to established ‘scientific’ knowledge. . . . If Qi and channels really exist, then modern ‘scientific’ views of the body-mind clearly need to be revised.”

Third Balance System Hypothesis

In 1983, Chinese physiologist Mon Zhao-Wei asserted that the critical factor of sensation propagation is its speed, usually in the range of 0.8 to 2.8 inches per second. This corresponds neither with the speed of the nervous system nor the speed of bodily fluids. He proposed that the acupuncture system is something new, which he called the third balance system.

According to his framework, outlined below in Table 2.1, the first balance system is the motor nervous system, which controls the movement of voluntary muscles, allowing for dynamic balance in rapid movements, like those occurring in sports and daily work, with a transmission speed of around 230 to 400 feet per second. The second balance system is the autonomic or vegetative nervous system; this regulates the slower dynamic activity of internal organs, such as breathing, digestion, and heartbeat. The third balance system is the meridian system, which transmits stimuli from the surface of the body to the internal organs, allowing for harmonious coordination between these two aspects of the body, thereby maintaining an even slower dynamic balance. The fourth balance system is the endocrine system, which maintains the slowest balance in bodily systems.

Table 2.1. The four balance systems in the body and the speeds of their signals, in feet per second.

| Balance System | Speed | Function |

|---|---|---|

|

first balance system: motor nerves |

330 feet/second transmission |

rapid posture balance |

|

second balance system: autonomic nervous system |

3.3 feet/second transmission |

balance of organ activity inside the body |

|

third balance system: meridians |

0.3 feet/second sensation propagation |

balance between organs and the body’s surface |

|

fourth balance system: endocrine system |

0.003 feet/second diffusion |

slow balance of the whole body |

While he did not elaborate details about this new balance system, he was the first physiologist who clearly stated that the mechanism of the acupuncture system could be an unknown new structure. If this new structure was discovered, it would necessitate a completely new chapter in physiology.

The third balance system predicted by Wei is in fact the dissipative structure of electromagnetic fields in living systems, discovered ten years later. To some extent this discovery reconciles the function of the mysterious acupuncture system with its corresponding structure. The discovery of this dissipative structure, which can be thought of as an invisible rainbow and inaudible music inside and around the body, is not limited to opening a new chapter in physiology; it will also facilitate revision of the scientific views of biology, psychology, and medicine.

Wave Guide Channel Hypothesis

On a personal note, I was surprised when my research revealed the existence of another visionary who made a similar prediction long before Wei and Maciocia. In 1959, Chinese physicist Bi-wu Zhang, from Qingdao Medical College, contended that modern medical research focused too heavily on the interactions of materials and not enough on the interactions of energy, that Western medicine overemphasized the importance of solid particles—molecules and atoms—while almost completely ignoring the waves in human bodies and the influence of changing factors such as light, electromagnetic fields, and cosmic rays.

The key point of his wave guide channel hypothesis was that the human body contains many tubelike and sheetlike structures, which are composed of heterogeneous media. These media interact with visible light in differing ways. Stated scientifically, they possess varying reflection coefficients, refraction coefficients, and polarization spectra toward visible light. These varying properties allow us to study these structures with the naked eye and the microscope. It can be assumed that these structures also vary in their interactions with infrared rays and microwaves, which are plentiful in the body. Therefore, the structures formed by these different materials interact to create a wave guidance system that directs the transmission of electromagnetic waves inside a body.

Figure 5.14. Chinese physicist Bi-wu Zhang (1920–1992), the first person to point out the important role of electromagnetic waves in the acupuncture system and other holistic forms of medicine.

Zhang regarded the concept of internal Qi in the theory of Traditional Chinese Medicine to be electromagnetic waves within the human body and named these electromagnetic waves Qi-photons. He speculated that:

• Qi-photons in the body had the same importance as materials—molecules and atoms.

• The relationship between different meridians, between meridians and their acu-points, and between meridians and corresponding organs could be explained in terms of a wave guidance system.

• The line with the highest probability of finding Qi-photons would be the axis of a meridian, around which there may be a tubelike distribution of Qi-photons that form its boundary.

• The slow speed of Qi or sensation propagation along meridians could be attributed to the “group speed” of the traveling waves as they progressed along their path.

I first encountered Zhang’s work in China in 1994, after I had developed the idea of the electromagnetic structure in the body in Germany in 1992. I was stunned by the visionary brilliance of his hypothesis. He had proposed almost the entire mechanism of fields and waves within the human body. The only aspect that he had overlooked was the relatively minor step of considering dissipative structures of electromagnetic fields, although labeling this omission an oversight is unfair. The theory of dissipative structures was only developed in the 1970s by Belgian scientist and Nobel laureate Ilya Prigogine. The integration of the role of dissipative structures into an empirical analysis of the human body depended on subsequent mathematical advances such as chaos theory, fractals, and many other nonlinear mathematical problems, discussed in chapter 7.