2 British Commonwealth Occupation Force Japan, 1946–48

Wayne Klintworth

Memories of the heat and boredom of Morotai were soon forgotten when the members of 34th Australian Infantry Brigade arrived in Japan in February 1946. Their task as a part of the Australian component of the British Commonwealth Occupation Force was about to begin; the conclusion to long years of war and hardship. They had been, as had most Australians, conditioned by racial fear and the threat posed by Japan ever since it emerged as a major Asian power at the start of the century. That threat had become very real in 1942 and the memories of the bombing of Darwin, the submarine attack on Sydney, the bitter fighting in the islands, and the atrocities and inhuman treatment of prisoners, including Australians, were not forgotten or forgiven. The Japanese had now suffered the first defeat in their history and had surrendered virtually unconditionally after the intervention of the Emperor and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.1

Some resistance to the occupation was expected. Weapons and stores had been secreted away in anticipation of invasion and the suicidal determination of the Japanese was demonstrated at Iwo Jima and Okinawa as US forces closed on the home islands. Warnings of the possibility of some active operations were provided during briefings and training on Morotai. In the event, the occupation of Japan following the war was to be uniquely successful and without major incident, reflecting not only the nature of the occupation and the performance of the occupying forces but also the culture of discipline in Japanese society. The tour of duty with BCOF was historically and geopolitically important at the time, and although there were real dangers, it was also an operation for which the participants would subsequently have to struggle to receive full recognition.

At first, however, the Australian forces were wary and distrustful and had little sympathy, and indeed great bitterness and hatred towards the Japanese people. They expected that they would have to be harsh in their treatment of the Japanese and anticipated some form of enmity, perhaps open hostility.2 Arriving off southern Honshu, the Australians lined the decks of the transports and surveyed the beauty of the island-studded Inland Sea. As the ships came closer to Kure though, the evidence of a defeated nation became apparent. They were greeted by grim sights of the partly sunken remnants of the Imperial Japanese Navy and the gutted industrial shoreline of what was once the largest naval base in Japan. Scattered around in the sea were the remains of several battleships, cruisers and two aircraft carriers sunk at anchor in the US bombing attacks that coincided with the Potsdam Declaration of 26 July 1945. Included was the hull of the 11,000 tonne cruiser Aoba, which had led the Japanese squadron into the Savo Strait, near Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, on the night of 8 August 1942 where they sank the Australian cruiser HMAS Canberra and three US cruisers.3

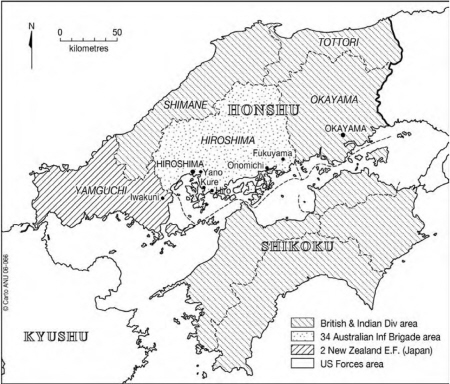

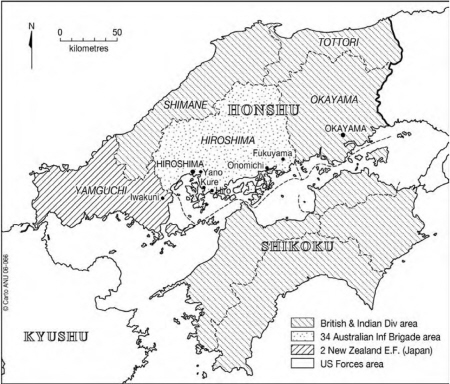

MAP 2: Southern Japan. The 65th, 66th and 67th Battalions served in the British Commonwealth Occupation Force in Japan in the Hiroshima prefecture. The 65th and 66th Battalions returned to Australia at the end of 1948, and until it was deployed to Korea in September 1950, the 67th Battalion, renamed 3 RAR, remained in the Hiroshima prefecture.

The advance party of 34th Brigade, travelling in the USS Stamford Victory, arrived at Kure, on the Inland Sea on 13 February 1946. As noted in the previous chapter, for many soldiers, their arrival brought feelings of satisfaction, happiness and triumph, tempered by a sense of hostility and memories of the war. There was also the sense of adventure and a great deal of curiosity in seeing Japan. On disembarking they were welcomed by the strains of a Royal Navy band playing ‘Waltzing Matilda’, and the clicking of cameras by Japanese newspaper photographers. There were shouts of ‘You’ll be sorry’ from the crew of HMAS Hobart to which the troops answered with the song ‘You’d Be Far Better Off In A Home’.4

The bulk of the troops of 34th Brigade arrived at Kure over the next eight days in HMS Glengyle, USS Pachaug Victory and USS Taos Victory. On arrival they were marched from the wharf to the railway station through streets lined with sombre Japanese who warily observed the battle-hardened veterans in their broadbrimmed hats. One member recalled that there was ‘no noise, except muffled footsteps in the slush and snow . . . the Japanese were apprehensive on the day of our arrival, they were [very] aware of our presence’. The Japanese referred to the Australians as ‘Gorshu Jin’ meaning ‘man of the south’ and avoided the connotations of the term occupation forces by referring to them as ‘Shinshugun’ meaning ‘a forward element’.5

Initially BCOF was located so as to be self-contained in southern Honshu, in the Hiroshima prefecture. Despite the lack of facilities and amenities, the prefecture was accepted as it was the only remaining area of some prestige value with port access that General Douglas MacArthur was willing to offer to BCOF. Much of the southern part of the BCOF area had been badly damaged by bombing, particularly Kure, and of course Hiroshima, the centre of which had been devastated by the atomic bomb.6

The brigade was taken to temporary barracks at Kaitaichi, a former Japanese Army stores dump. Kaitachi was by the sea, about 24 kilometres north of Kure, and only a few kilometres from Hiroshima. The wooden buildings to be occupied had been storage sheds and some were without floors. ‘Space was their only attribute; otherwise they were cold, draughty and comfortless. It was a most depressing area, made worse by the hinterland of paddyfields and small unprepossessing villages.’ To make matters worse some of the Australians arrived for the Japanese winter clothed for the tropics; extra blankets and clothing arrived later. These circumstances combined with the snow and intense cold indicated that the tour of duty in Japan was going to be difficult as well as demanding. Despite the highly critical newspaper reports back in Australia about the conditions in Japan, there were few complaints from the troops who quickly got on with their job.7

Throughout its existence an Australian officer always commanded BCOF. Initially Lieutenant General J. (later Sir John) Northcott was Commander-in-Chief until 15 February 1946 when he became Governor of New South Wales. Lieutenant General H.C.H. (later Sir Horace) Robertson replaced him until November 1951 when Lieutenant General W. Bridgeford took command until the end of the occu-pation. Although under the operational control of the US Eighth Army, the Commander-in-Chief BCOF had direct access to General MacArthur on matters affecting the operational control of the force. The Commander-in-Chief was also responsible for the maintenance and administration of the BCOF. On matters of policy and administration he was responsible to the various contributing governments through the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Australia (JCOSA), established in Melbourne.8

The primary objective of the occupation forces was to ensure the implementation of the terms of the unconditional surrender that ended the war in September 1945. The task of exercising military government over Japan was the responsibility of the US forces. In its area of responsibility, BCOF was required to maintain military control and to supervise the demilitarisation and disposal of the remnants of the Japanese war machine. In addition, BCOF was ‘to represent worthily the British Commonwealth . . .’ and ‘to maintain and enhance British Commonwealth prestige . . .’, not only in the eyes of the Japanese but also of the rest of the world, particularly those in Asia. They were also to ‘impress on the Japanese people, as far as possible, the democractic way and purpose in life . . .’, which they would be shown for the first time only by virtue of the presence of the allied occupation forces. To Lieutenant General Northcott the job in Japan was ‘to play our part in the winning of the peace which is just as important as the task we had in winning the war . . . The success of our job will depend a great deal on the behaviour, discipline, military efficiency of every individual in the force as part of the Commonwealth team.’9 These were high ideals, but it remained for the soldiers to put them into practice.

Temperatures in February and March often did not rise much above freezing point and it was not long before braziers and fires were burning to provide warmth. The camp at Kaitaichi and its routine were quickly established. Japanese contractors and labourers were employed under strict supervision to assist in construction and maintenance. Instructions were issued on the treatment of the Japanese camp labourers, on routine, local leave, on dress, bearing, health, hygiene and the black-market. There were also warnings about VD and the dangers of locally brewed spirits. Particular attention was to be given to restrictions on fraternisation. This was to cause some controversy and resentment among the Australians, because the restrictions on the US forces were less rigorously applied, and because there was an initial lack of recreational facilities.

These restrictions were aimed at establishing a strict and ‘proper’ relationship between the occupation forces and the Japanese. As one historian later observed, the ‘conduct of Australian troops in Japan could have had a disastrous and lasting influence on post-war relations . . . had the troops not behaved with scrupulous correctness, very strong discipline . . . [had to be] maintained’. The need for strict discipline was to place great pressures on junior officers and NCOs requiring them to set and maintain the necessary standards and the level of activity through training, sport and recreation programs. According to one occupation force officer, ‘the real success came from keeping the units busy . . . [and] an excellent level of discipline was maintained’.10

Once the initial reconnaissance and planning were completed, the three battalions of 34th Brigade were deployed to conduct their occupation duties. The prefecture was divided into three areas of unit responsibility. The 65th Battalion was to be responsible for the eastern area, the 66th Battalion for the centre and the 67th Battalion was given the western area.11 Because of the remoteness of the eastern area and the availability there of the former naval air station barracks, it was decided to relocate 65th Battalion, and in late March the bulk of the battalion moved from Kaitaichi to the barracks at Fukuyama.

The congestion at Kaitaichi was further eased when the Brigade Headquarters and 66th Battalion moved to Hiro in July after the troops of the British and Indian Division (BRINDIV) had moved out. The 67th Battalion continued to use the barracks at Kaitaichi for the next two years, although its sub-units were to be widely dispersed throughout its area of responsibility.

With the departure of the BRINDIV troops from Hiroshima prefecture in June 1946, 34th Brigade took over responsibility for the whole of the prefecture. In July the Brigade Headquarters moved from Kaitaichi to Hiro, on the shores of the Inland Sea, where it remained throughout the occupation. During these first few months there was an important command change within the brigade as Nimmo was promoted to major general and recalled to Australia to command the 1st Military District. Brigadier R.N.L. Hopkins replaced him from 18 April.

Enforcing SCAP Directives—65th Battalion

Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel R.H. ‘Drover Dick’ Marson, 65th Battalion had a short period to settle into their barracks at Fukuyama. At the time the battalion was no more than two-thirds of its full strength with 24 officers and 408 other ranks. Most would be required almost immediately for guard duties to escort trainloads of Koreans travelling from northern Japan to be returned home. The trains carrying the Koreans (usually about 720 on each) and their escorts travelled on a thirteen-hour trip from Fukuyama to Hakata or to Moji, where they were met by American forces. By the end of March some 13,395 Koreans had been escorted to Hakata.

‘Sakura’ (cherry blossom) season was just beginning to transform the countryside in April as 65th Battalion began its regular duties to confirm Japanese compliance with the directives on disarmament and demilitarisation. The requirements were outlined in an instruction issued on 25 April, which directed that any military stores and installations were to be located and secured, black-market activities were to be stopped and general surveillance of the Japanese was to be maintained. Furthermore, ‘Every Japanese will be regarded as a potential agent for . . . subversive Japanese organisations or under cover espionage, or organisations of other nations. All ranks should . . . adopt an attitude of suspicious alertness . . .’12

Each week a census of civilian attitudes was conducted within the battalion area. It soon was apparent that while most Japanese were indifferent or resigned to the presence of the occupation forces, some regarded it as good. In general, they cooperated with the requirements of the occupation and in return they were free from unwarranted interference with individual liberty and property rights. In accordance with SCAP decrees, historical, cultural and religious objects and shrines were protected and preserved, and subject to the requirements of military security, freedom of speech, press, religion and assembly were allowed.

In view of the presence in Japan of hundreds of thousands of repatriated soldiers and the potential for the formation of subversive organisations, the possibility of some organised resistance or guerilla activities could not be ignored. In anticipation of such eventualities, all units had to prepare and rehearse defensive plans.

65th Battalion’s plan for the Fukuyama–Onomichi area was prepared in April, and though events were to prove there was never any danger of an uprising by the Japanese, this was unknown at the time. Greater danger emerged from the possibility of natural disasters, such as typhoons, floods, earthquakes and tidal waves. Disaster plans for these events were also prepared in each area to protect the occupation forces and their installations, and to provide assistance and relief to the Japanese.13 The battalion began regular patrols and road reconnaissances around Fukuyama.

As two battalion officers later explained:

The Intelligence Section would be given ‘targets’ to investigate by BCOF HQ, in the form of grid references for dumps of Japanese war materials. Int[telligence] Section would be given an interpreter from the Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Section (usually a Sergeant) . . . [They] would locate the dump and then recommend the appropriate disposal action . . . [The] usual approach was to ask for the headman of the village or the ‘responsible person’. The ‘responsible person’ was the man who at the end of the war had been entrusted with the key to the store, but often would be unaware of the contents. The gear was usually untouched. It might be vacuum tubes for radios or even mustard gas . . . Warlike stores were destroyed. Other stores were kept for use by the administration or returned to the Japanese economy.

Information on ‘targets’ came from US Counter Intelligence, which received most of its data from the Japanese themselves.14

The collection of weapons was also carried out with the assistance of the Japanese.

In each area the local police chief was instructed to collect and label all arms in his area and display them in his police station. Swords classified as ‘works of art’ were returned to their owners while the remainder of the weapons were confiscated.15 One of the most important tasks of the occupation forces was to supervise the democratisation and political reform of Japan. The involvement of the Australians, however, was limited to supervising elections, and the first general elections in postwar Japan were held in April 1946. Each battalion provided several small teams of observers to cover the elections and despite some extremely vigorous campaigning by some of the parties no serious incidents were noted. The number of voters turned out to be higher than had been forecast and although the proportion of women who voted was low, it was regarded as better than had been hoped for.

Later in April, D Company, under the command of Captain C.H.A. East, was deployed to Onomichi on the coast, south-west of Fukuyama. The population of Onomichi was approximately 80,000 and D Company was given responsibility for the enforcement of SCAP directives and ensuring that law and order prevailed. It was known to Captain East that Onomichi was a black-marketing and smuggling centre with contraband being shipped from Japan to places such as Formosa. Such criminal activities involved mainly Koreans and Formosans with the Japanese police themselves being quite afraid of the former. The company started work and met with immediate success. In one raid on some warehouses they found about 100 tonnes of foodstuffs while a patrol on the island of Mukai Shima came across a large oil dump containing about 14,000 drums of oil. One of the most successful Australian operations was conducted on 5 July, when at 1.00 am the company raided two 80-tonne ships off Onomichi. With information from a Korean national, a joint operation was planned and put into effect by Captain East. ‘One understrength platoon plus interpreter was nominated as the strike force, on a commandeered motorised fishing boat. One other platoon was earmarked as a reserve, while . . . [the] Headquarters was set up with the Chief of Police at his Police Station. An observation team of plain clothes Japanese police watched the activities of both vessels.’ When one of the vessels slipped its moorings the pursuit by the strike force began. ‘After ignoring calls to heave-to, Captain G. McLean (company second-in-command) ordered a Bren gun mounted in the bow [to open fire] . . . a half magazine was fired . . . the target vessel stopped and was searched.’ The search revealed a hoard of contraband, including £7,000 worth of gold, $2,000 in US currency, a bag of pearls, a quantity of medical supplies and about 80 bags of rice. The second vessel was also searched but no contraband was found.16 Although this raid was unopposed, the risks became apparent when divers later recovered a number of weapons that had been thrown overboard by the crews of the raided vessels. The success of the operation was in part due, surprisingly, to the effective and efficient cooperation of some of the ‘former enemy’. Results such as these proved to be a great boost to morale.

Many of the occupation duties, particularly in 1946, involved activities designed to reinforce upon the Japanese the lesson of their defeat. In addition to normal guard requirements in their own areas of responsibility, the brigade provided guards in Tokyo in rotation at various locations in the city including the Imperial Palace with the other units of BCOF. Large crowds of Japanese and of other occupation force members often turned out to watch the occasions and be impressed by the drill and bearing of the guards with their blancoed webbing. In May–June, A Company represented the 65th Battalion in a composite AIF battalion and in September the complete battalion went to Tokyo. Accommodated at Ebisu Camp, the duties in Tokyo also allowed off-duty members of the battalion an opportunity for local leave in the city. A former member recalled that: ‘Guard duty in Tokyo was popular, not only for social reasons. The soldiers enjoyed the ceremonial [aspects] . . . the symbolic message to the Japanese was unmistakable . . . [and] it was the New Zealanders, not Australians, who went fishing in the Imperial Palace Moat using hand grenades (and then sold the Imperial carp!).’17 After the Tokyo guard, companies of the battalion were deployed for guard duties in Kure, Hiro and on Eta Jima. Another task, which was carried out by all the battalions throughout the prefecture, was the flag march. Units or sub-units, bearing arms and carrying flags, would parade through the cities, villages and countryside. D Company of the 65th Battalion conducted such a march through Onomichi on 4 May led by the battalion band and met an ‘enthusiastic’ response from the Japanese who watched.

Towards the end of the year, construction work began on permanent barracks at Fukuyama, and this continued for the next seven months before the battalion was able to move in. In the meantime the battalion was scattered in a number of locations carrying out duties, mainly providing guards. In January 1947, A Company was at Hiro, B Company and C Company on Eta Jima, D Company, less one platoon, was at Onomichi, Battalion Headquarters was at Onomichi, Headquarters Company at Fukuyama, and one platoon of D Company was at Kobe Base.

Members of the 65th Australian Infantry Battalion marching off to relieve guard posts outside the Imperial Palace, Tokyo, 26 September 1946. The battalion had just taken over guard responsibilities from the 2/5th Royal Gurkha Rifles (AWM photo no. 131480).

It was noticeable that even during the last months of 1946 the occupation duties were changing and becoming less onerous. Less effort was required to conduct the supervision of the demilitarisation of Japan and most activity centred on the guard duties, which enabled the battalion to devote more time and attention to training.

The fighting efficiency of the battalion was not Lieutenant Colonel Marson’s only concern. By October 1946 he was concerned at the increasing involvement of members in minor crime and black-market activities. The rising incidence of petty crime in 1946 was a problem throughout the occupation forces including the Australian component. To a large extent it was a result of the circumstances the occupation forces were placed in. There was a great deal of temptation in the widespread black-market in postwar Japan; army rations, equipment and clothing were much sought after. Bartering and exchange of cigarettes or food, sometimes for yen, were common occurrences. The latter was partly reduced by the introduction of British Armed Forces Special Vouchers, a sterling paper currency that was used to pay soldiers. Incidents of involvement in larger scale criminal activities did occur amongst the occupation forces. Australians who were caught were disciplined, some were court-martialled and returned to Australia. An important part of the answer to the problem, however, lay in the provision of amenities and entertainment, the organisation of sport and particularly the conduct of training.18 Training routine within the 65th Battalion was established and the companies began a series of field firing and range practices for the first time since arriving in Japan. The field firing took place at Hachihonmatsu, some sixteen kilometres north-east of Kaitaichi.

Training continued during 1947, and although the sub-units were scattered and there were many personnel changes, individual training began to include minor tactics, map reading, fieldcraft, as well as drill and weapons training. Specialist training for signallers, mortarmen and machine-gunners also commenced. Sport and competitions remained regular afternoon activities, and were important in building esprit de corps. The institution in 1947 of the Gloucester Cup, a military skills competition between the regular battalions, attracted considerable attention and keen competition as the platoons sought to represent the battalion.19 The new barracks at Fukuyama were not quite completed in May 1947 when the battalion moved in, but for the first time in many months the unit was together in one location. The barracks were much more suitable and comfortable, and posed less of a fire risk than previous accommodation. Eventually the facilities would include a rifle range, swimming pool and tennis courts. The barracks were named Vasey Barracks in honour of the commander of the 7th Division, 1942–44, Major General George Vasey, who was killed in an aircraft crash on 5 March 1945; it was from the 7th Division that the majority of members of the battalion had come when it was raised in 1945.

With the withdrawal of the British and Indian forces in 1947, the 65th Battalion’s area of responsibility was expanded to include the island of Shikoku. No garrision was maintained on the island; however, control over it was maintained by frequent visits, patrols and raids. On 25 June, for example, the commanding officer led a party to raid the Demobilisation and Repatriation Centre at Zentsuji. The area and buildings were cordoned off and searched but nothing was found.

The battalion strength in March 1948 was 30 officers and 426 other ranks; by July 1947 it had fallen to 28 officers and 232 other ranks. This rundown in strength was initially to prove a blessing in disguise, for whereas the occupation duties in 1946 required a large number of personnel, by 1948 this was no longer necessary. The changing nature of the duties in Japan became more pronounced in 1948. The changes allowed the units to be drawn in closer to the headquarters and the central area of Hiroshima without prejudicing their occupation responsibilities.

In March the 65th Battalion was notified that it was to move to Eta Jima after nearly two years at Fukuyama. Lieutenant Colonel Marson regretted the move ‘as the camp [at Fukuyama] and area are as perfect as could be desired’. Notice of the move coincided with the departure of Marson on 19 April, after 30 months as the commanding officer. Major T.E. Archer, the battalion second-in-command, assumed command and remained in this capacity until after the battalion returned to Australia in December 1948.

The move to Eta Jima was completed in May with Vasey Barracks being handed over to the US Army. The remaining months in Japan were to be onerous because of the low strength of the battalion. Guard duties were divided between Eta Jima and Tokyo, and in July it was necessary to send the whole battalion to Tokyo, because of its reduced strength.

Meanwhile, in response to severe manpower problems within the army back in Australia and because the cost of maintaining the bulk of the army in Japan could no longer be sustained, in June instructions had been received outlining the reduction and reorganisation of BCOF. This included the withdrawal and return to Australia of most of the major Australian units. The Citizen Military Forces (CMF) were to be re-formed in 1948 and would require large numbers of regular soldiers to train and administer them. It had also become apparent that most of the major tasks of the allied occupation were complete. The Australian government therefore decided to reduce the commitment of BCOF but hoped to retain some influence over the final settlement with Japan by the continued presence of at least a significant component of the Australian Army. In September 1948, it was advised that both 65th and 66th Battalions would be withdrawn from BCOF. The next few months were taken up with preparations for the return to Australia and the transfer of some men to the 67th Battalion, which was to remain in Japan. The move back to Australia began on 24 September when an advance party departed in MV Australia. On 7 December the battalion sailed for Australia in HMAS Kanimbla.

Guard Parades and Guard Duty—66th Battalion

Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel George Colvin, 66th Battalion arrived in Japan with a strength of 27 officers and 553 other ranks. After settling in to the camp at Kaitaichi the battalion began its duties in March 1946 with local patrolling and the deployment of A, B and C Companies under the command of Major R.G. Jenkinson to Kure for six weeks. This force, known as Jenko Force, was tasked to guard various tunnels and dumps in Kure and Kure wharf. The tasks very rapidly took on the seriousness expected. By the end of March there had been several occasions when shots were fired at suspects who refused to halt at night when challenged; in addition, a number of Japanese civilians who were found in the vicinity of the ammunition dumps were arrested. Some of the Japanese were found to be in possession of stolen food and were handed over to the Japanese police. A mobile picquet consisting of one officer and 25 other ranks was also maintained on stand-by at all times in case of emergency. On many occasions they were employed to put on demonstrations of strength to the Japanese. On 21 March, for instance, under Lieutenant D.R. McLeod, they deployed to the railway station in Kure. Armed in battle order with rifles and bayonets, Owen submachine guns and light machine-guns, all with charged magazines, they leapt from their transport and secured and searched the buildings. After ten minutes they returned to their vehicles and moved on to a market place where a similar demonstration was put on. On such occasions, however, the response of the Japanese might have seemed disconcerting. They did not appear impressed with these displays of military efficiency and either ignored them or looked on with little expression.

Troops of the 66th Australian Infantry Battalion (Jenko Force) overlooking Ninoshima on 27 May 1946. The inlets, islands, pine trees and terraced fields became familiar to the Australians who were carrying out reconnaissance and security patrols on the various islands of the Inland Sea (AWM photo no. 129959).

From April the battalion was widely scattered with elements in Kaitaichi, Hiro, Hachihonmatsu, Tokyo and on the island of Eta Jima. Companies were rotated through the patrolling and guard duties on Eta Jima, with C and D Companies deployed there in late April. Their tasks were to guard the Headquarters BCOF area and the extensive Japanese weapons and ammunition dumps on the island. Once established they prepared inventories of the ammunition and equipment and then assisted with the disposal of the ammunition; many thousands of cases of mixed ammunition were dumped at sea. Some of the ammunition was found to have come from Britain, France, Germany, Japan, Italy as well as some consigned from ordnance depots in Sydney. As it was usual for one of these companies to be fully employed providing guards and the other to provide patrols to secure the arsenal, there was little time for training. During the absence of C and D Companies, security patrols around Kaitaichi were maintained by the remainder of the battalion and in May–June B Company went to Tokyo to represent the battalion in the combined guard. Work to refurbish the proposed new barracks at Hiro began in May.

Another task required a platoon to occupy the Hachihonmatsu area to guard the ammunition dumps at Kawakami and Yonemitsu. 7 Platoon, A Company, under the command of Lieutenant J.W. King, was the first platoon to be given this task, and was confronted with a variety of activities. On 2 May patrols in Saijo were required to disperse crowds of Koreans who had taken advantage of their ‘free’ status and were demonstrating against any form of Japanese authority. Platoon patrols collected information on the terrain and civilian activities, and observed the movement of many demobilised Japanese servicemen passing through Saijo each day. The major task was, however, to guard and later assist with the transfer and disposal of the tonnes of ammunition, explosives and poisonous gases in the magazines. In August 12 Platoon, B Company, under the command of Lieutenant H.M. Fox (who had been a prisoner of the Japanese during the war) took over this duty, and assisted in the disposal of 508 tonnes of mustard and lewisite gases, 267 tonnes of explosives, and the transfer to BCOF units of 92,000 litres of gasoline and oils. The destruction of the ammunition and explosives took place at Haramura, formerly a Japanese Army manoeuvre area, which was to become the main field training area for the three Australian battalions during the occupation and later for the Commonwealth forces during the Korean War.

Members of the 66th Australian Infantry Battalion (Jenko Force) at Kanokawa on Eta Jima inspecting Japanese midget submarines along with a large quantity of 16-inch naval shells lying on the beach (AWM photo no. 129967).

On 10 July the main body of the battalion moved the short distance from Kaitaichi to their own camp, known as North Camp at Hiro. The barracks here had previously been part of a Japanese arsenal and provided accommodation for workers. They were an improvement on the warehouse accommodation at Kaitaichi; however, work on improving the amenities at Hiro began almost immediately. This included establishing a sportsground, theatre, a unit beer garden and a snack bar. In September construction work on the permanent barracks began.

The move to Hiro was greeted with mixed feelings. They had been in Kaitaichi for six months and the Hiro area was found to be uninteresting and, being poorly drained, unhealthy. The battalion now had an area of responsibility of approximately 2080 square kilometres in the centre of Hiroshima prefecture. Because this area included some 60 islands in the Inland Sea, patrols included visits to some of them. From August the battalion, except for the platoon at Hachihonmatsu, was together at Hiro, and for the remainder of the year was active with occupation duties. Two major operations during this period were Operation Foxum and Operation Ludo. Operation Foxum was a brigade operation intended to detect any contravention of SCAP Directives 519 and 642 on education and prostitution. The operation began on 2 September with teams conducting a snap inspection of nineteen schools searching for and confiscating militaristic and ultra-nationalistic propaganda and books. Phase two of the operation involved the surprise investigation of brothels to detect the forbidden practice of licensed prostitution. The SCAP Directive had abolished licensed prostitution and declared null any contracts binding women to serve as prostitutes.20 Operation Ludo was conducted on 26 September when B Company (Captain A.P.A. Denness) raided the town of Kinoe and the shipping in its harbour. The raid, in response to the discovery of a smuggling boat on 19 September, was less successful and revealed no further contravention of directives.

Training was limited for the remainder of the year but an NCO training cadre was established to train junior NCOs in their responsibilities, particularly drill, military law, instructional method, sentry and guard procedures. In August companies began field-firing exercises and field training at Haramura. Activity programs for the companies now comprised four hours of formal training each day, including organised PT, drill and lectures. The emphasis changed to drill in December as the battalion prepared for guard duties in Tokyo, beginning on 6 January 1947. November and December 1946 were also a period of reorganisation and administration as replacements from Australia arrived and members prepared to go home on leave or discharge. By mid-November the battalion strength had risen to 30 officers and 885 other ranks.

The availability of amenities improved later in the year when the Anzac Club in Hiro was opened for all BCOF other ranks and the Brigade Holiday Club began offering hotel accommodation in Tokyo, Kyoto, Kobe and Beppu. Local leave had to be curtailed in September due to outbreaks of cholera and many areas were placed out of bounds. Two buildings of the new barracks at Hiro were completed in late October and by the end of December the whole battalion had moved there. The Pioneer Platoon helped transform the area by constructing sports fields, and even ‘managed to convert a static fire fighting water tank into an adequate swimming pool, which was no mean feat in view of the controls on resources’.21 Despite the improving conditions and increasing attention to training, there was a disturbing increase in petty crime and an unenviable record of venereal disease. These problems applied generally amongst the Australian component of BCOF and not only within the three battalions of the brigade. Those members involved in crime were dealt with accordingly; preventing the troops from catching venereal diseases was a more difficult problem.

The limited amenities and provisions for leave were closely associated with an increasing incidence of venereal disease among the Australians in 1946. Prostitution was a common occurrence in the Hiroshima area; it had always been permitted by the Japanese, and in the economic conditions that existed after the war it was the only way some women could survive. By June 1946, the rates of incidence (ten to fifteen cases confirmed per week within the brigade) were of such concern to Brigadier Hopkins and the unit commanders that a concerted campaign was begun to reduce the incidence and alert soldiers to the dangers. The steps taken included placing brothel areas out of bounds, lectures and films, disciplinary action, loss of privileges, the establishment of unit anti-VD teams and treatment centres, and the issuing of a brigade instruction on the control of VD on 28 June 1946. Although the incidence of VD was reduced the problem persisted and was adversely reported in Australia. The reports were eventually raised in parliament and resulted in special investigations being initiated. These concluded that the press reports were greatly exaggerated and that the incidence of crime and venereal disease was relatively lower than that in major Australian cities.22 Duties in Tokyo began on 6 January 1947 with the ceremonial guard change at the Imperial Palace. The battalion took over their responsibilities from 5th/1st Punjab Regiment. One of the highlights of the tour was the battalion parade on 27 January on the Plaza to commemorate Australia Day. A number of important guests were in attendance and witnessed the investiture by Lieutenant General Robertson of members of the battalion with decorations awarded during the war.

The flag march at Saijo on 20 September 1946 by C Company, 66th Battalion. Spectators watched from the doorways and windows and ‘clapped as the Australians marched by, but the applause was obviously too well rehearsed to be sincere’. Above the saluting base of the Saijo branch of the Geibi Bank were hung the flag of the 66th Battalion, the Union Jack and the Australian flag. The salute was taken by the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel G.E. Colvin. The local chief of police, mayor and town officials were invited to be present. In the photograph, 14 Platoon, led by Lieutenant D.R. McLeod, is marching past (AWM photo no. 131987).

For 66th Battalion, the period after returning from Tokyo was marked by a more vigorous training program. General education in arithmetic, English and social studies was required for six hours each week and individual training for all ranks was given increased emphasis in preparation for unit training in the coming summer. The battalion established an NCO school at Hachihonmatsu and conducted range practices and courses in small arms at Haramura. During this period of activity command of the battalion passed from Lieutenant Colonel Colvin to Lieutenant Colonel Malcom McArthur. McArthur actively supported the battalion band, then under Sergeant H.J. Silk, and selected the Japanese popular tune ‘The Apple Song’, now entitled ‘Ringo’, as the battalion march.23

Training activities expanded in August with a battalion-controlled training program commencing on 10 August. The battalion, less D Company which remained on guard duties at Hiro, marched to their respective company training areas near Haramura and at Sambe Yama (Shimane prefecture). Using tactical doctrine that emphasised the techniques employed in north-west Europe in 1944–45, the collective training culminated with Exercise Bunger on 25–26 August, which was a demonstration of a company attack supported by RAAF Mustangs, a troop of guns from A Field Battery and the supporting weapons of the battalion.

Much of the remaining months of 1947 and 1948 were taken up with increasingly onerous guard duties and then preparations for the return to Australia in December 1948. Guard detachments were sent to Kaitaichi, Eta Jima, Kobe and the battalion went to Tokyo in November 1947, in May and in September 1948. The strength of the battalion had fallen substantially (22 officers and 208 other ranks in July 1948) and the organisation of training became very difficult. One of the main activities of this period was the preparation and competition for the Gloucester Cup. McArthur’s command of 66th Battalion ended in February 1948 when he returned to Australia.

The second-in-command, Major C.F.G. McKenzie, assumed command until the appointment of Lieutenant Colonel Stuart Graham, in August.

After the announcement in September that the battalion would be withdrawn from BCOF, preparations began for the return to Australia. As with the 65th Battalion, an advance party departed in September and transfers to the 67th Battalion began. The battalion sailed with the 65th Battalion in HMAS Kanimbla on 7 December.

Training in Japan—67th Battalion

On arrival at Kaitaichi, 67th Battalion occupied accommodation vacated by the 186th US Infantry Regiment. Shortly afterwards they escaped the draughty huts and moved into the nearby workmen’s quarters of the Nippon Steel Company, which were found to be more comfortable with four or five men to a room. The battalion, in February 1946, was about two-thirds of its full strength with 28 officers and 513 other ranks, and was under the command of Lieutenant Colonel D.R.

Jackson. Occupation duties commenced at the beginning of March when A, B and D Companies where deployed to Otake and Ujina for tasks which were to occupy the battalion for much of the next two years. A Company, under command of Captain R.R. Escott, went to Otake, about 56 kilometres south-west of Kaitaichi, with the task of supervising the Japanese repatriation centre in the former naval barracks. B and D Companies, both under command of Captain J.C. Paterson, had a similar task at Ujina, which was a waterfront suburb of Hiroshima. Ujina itself was used as a repatriation centre for non-Japanese, including Koreans, Ryukuans and Formosans before they returned to their homelands. The island of Ninoshima, three kilometres offshore from Ujina, was used for the processing and quarantine of Japanese returning from overseas. Ujina was the largest of the two main repatriation centres for the whole of Japan.

The role of Otake Force and Ujina Force, as they were known, was to ensure that the repatriation centres were conducted as required by allied policy. It was necessary to ensure customs, quarantine and medical procedures were carried out, and that the incoming Japanese were made aware of the presence of the occupation forces. Brigadier Hopkins described the arrival of the incoming Japanese soldiers, sailors and civilians:

Here we saw the reception, customs search, medical examination and demobilisation of nearly half a million Japanese soldiers returned from operational areas overseas.

The delousing system was necessary, not only against lice, but to prevent the introduction of insect-borne tropical diseases . . . Picture a large shed with files of soldiery waiting in front of a row of young women, each armed with a high-pressure DDT spray! The whole effect was rather like a shearing shed. The victim was literally seized and a jet of DDT powder sprayed on his hair, down his neck, front and back, beneath his waist-belt front and back. He was then pushed out of way, and the next in line took his place.24

HQ and C Companies of the battalion were also deployed in March, but their task was on the island of Eta Jima. Under the command of Major I.B. Ferguson, they were required to obtain information about the military installations on the island and to destroy anti-aircraft guns, powder, ammunition and equipment. Known as Eta Jima Force, they were accommodated in the former Japanese Naval Academy. Patrols soon confirmed the island to be a huge arsenal, honeycombed with tunnels, warehouses and factories all containing many thousands of tonnes of materials. The local population consisted of some 60,000 people, most of whom were fishermen or farmers. In general, these Japanese were also found to be apathetic towards the occupation, although some were friendly and others were obviously afraid. Major Ferguson also had the duty of regularly inspecting several former Imperial Japanese Navy warships at anchor nearby, some of which still had their crews onboard.25 The task on Eta Jima ended on 26 March when the 2nd New Zealand Division Cavalry Regiment arrived to take over the responsibility.

Training opportunities were limited during the first few months of 1946. Nonetheless, drill and weapons training were daily activities, and a training cadre was established to assist in unit training. By May, range practices were being conducted; and in July, field-firing practices began at Haramura. In May the battalion was represented by C Company in the AIF battalion on guard duties in Tokyo. This was the first occasion that Australian or BCOF troops were to carry out this task and it had been decided that it was appropriate for the first guard to be a composite battalion. The AIF battalion included troops from the three battalions and was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Jackson.

Private Gallagher of the 65th Battalion watches over repatriates coming ashore on 27 June 1946. The repatriates were formerly Japanese prisoners of war from Singapore. On arrival at Ujina ‘they received inoculations, DDT sprays and a cup of tea’ (AWM photo no. 131645).

Aside from the continuing commitment to supervise the repatriation centres in 1946, the battalion also carried out a number of patrols into the western and northern sectors of Hiroshima prefecture. Although concentrating on Hiroshima and its surrounding areas, reconnaissance patrols extended to Miyoshi, Yoshida, Kake and Shobara. A number of these patrols were known as ‘mob recce’ and involved surveillance of demonstrations, particularly by Koreans, but also by Japanese workers protesting about their poor working conditions. Other major responsibilities were the provision of guards at the British Commonwealth Base in Kure and HQ BCOF on Eta Jima, and assistance with the disposal of equipment on Itsukushima. It was during one of the guard duties in Kure that one of the most serious accidents involving Australian troops occurred. On 24 June two members of the battalion were killed and fifteen were injured when a train at a level crossing struck their truck. In September the battalion participated in the brigade’s Operation Foxum. For much of this time, however, the battalion was widely scattered in the areas of company responsibilities.26 The attitude of the Japanese was continually observed and reported by all the occupation forces. Initial impressions of the men were of apathy and disinterest; later it was noticed that there appeared to be a desire amongst many of the Japanese to see the occupation continue, quite probably because they found that they fared better under the new administration. Attitudes were generally found to be favourable and a survey of public opinion conducted in Hiroshima City on 5 September appeared to confirm this fact. The Japanese seemed particularly impressed by the bearing and discipline of the occupation forces.

By January 1947 the strength of the battalion had increased to 32 officers and 958 other ranks. As the other battalions had found, occupation force duties were becoming less demanding on the unit and more routine. Training, particularly of the reinforcements and junior NCOs, was given a higher priority. Time was also now available for the conduct of unit specialist courses such as for signals operators, regimental police, intelligence staff and medical orderlies. On 5 March, Lieutenant Colonel Jackson departed from the battalion and was replaced on 21 March by Lieutenant Colonel Fergus MacAdie. In the intervening period, the second-in-command, Major Ferguson, administered command as he was to do on many occasions.

In April the battalion took its turn in providing the ceremonial and non-ceremonial guard duties in Tokyo, relieving the 1st Battalion, Mahratta Light Infantry Regiment on a ceremonial parade on the Plaza on 3 April. They were in turn relieved by the 4th New Zealand Guard Battalion on 3 May. The battalion then returned to Kaitaichi and began once again its duties at Ujina and Otake. Additional duties were to provide a platoon as guard at the Brigade Field Punishment Centre on Ninoshima and the provision of demonstration troops for the British Commonwealth Army Training School (BCATS). Warning was also received in May that the battalion would move to Okayama in November following the withdrawal of the 268th Indian Infantry Brigade.

In July the battalion established a training camp at Nippombara, a former Japanese field-firing range. Under the supervision of Major Ferguson, the companies rotated through concentrated training and field-firing exercises. Training for the first Gloucester Cup competition at the end of the year was begun in September. In a closely contested competition, 67th Battalion were eventual winners. The significance of this competition, however, lay more with its contribution towards the development of team spirit within the battalions.

One of the battalion’s more significant operations was conducted at the end of September 1947. Operation Cave was a raid on a large copper mine at Niihama, on Shikoku Island. A and C Companies under command of Major A.F.P. Lukyn carried out a surprise seaward approach to isolate the mine area. They then searched unsuccessfully for precious metals, war materials and black-market food supplies. In November the battalion began its move to Okayama where black-market activities had flourished and the battalion patrolled the areas where it occurred.

The diminishing nature of duties and the reduction in the strength of the occupation forces in 1948 were reflected in the tasks of the 67th Battalion. In February and March there were guard duties in Tokyo, and in May, after seven months at Okayama, the battalion, now with only 276 members, moved to Hiro after handing over Okayama prefecture to US Forces. With the announcement of plans to reduce and reorganise BCOF, preparations were made for rebuilding the battalion to full strength. The strength of the battalion, however, continued to fall as it was not possible to disband the other battalions, and recruiting in Australia was very low. By October the battalion consisted of only 24 officers and 212 other ranks. In July 1948, command of the battalion passed to Lieutenant Colonel Ken Mackay.

In the latter months of the year the battalion conducted field-firing practices at Haramura and range practices at Hiro. With the impending withdrawal of the other two battalions, NCO cadre training began in anticipation of an infux of reinforcements. However, the slowness of the arrival of reinforcements caused Mackay to make representation to Brigadier Hopkins and the battalion was forced to use Japanese guards to secure their lines in October when they were required for guard duty in Tokyo.

On 20 November the brigade marched through the streets of Kure for the last time, and the final parade in Japan was held on 22 November on the parade ground in Hiro. The occasion was not regarded as a festive one. The conditions and fortunes of the BCOF had changed over the previous two years. Now the number of troops on parade was few and the spectators numbered only a couple of dozen. When 65th and 66th Battalions departed on 7 December, 67th Battalion was still well under strength. In December reinforcements from the other Australian components of BCOF brought the battalion up to 23 officers and 324 other ranks, enabling it to re-form its second rifle company. Guard duties were still required but the task had been made less burdensome with the reduction of the requirement in Tokyo to about one company. A guard company was established within the battalion for this purpose.

The battalion continued its other occupation duties in December. B Company, under command of Major East (recently arrived from the 65th Battalion), was ordered to Ube on the coast to re-establish control following a series of violent demonstrations by large numbers of Koreans. In ‘a display of strength . . . the company paraded through Ube’s main thoroughfares with fixed bayonets twice over a three day period’.27 No further incidents occurred and the company returned to Hiro with the grateful thanks of the mayor and the chief of police.

The battalion also took part in Operation Interception involving sea patrols to parts of Shikoku Island in search of illegal Korean immigrants. Nine illegal immigrants were apprehended and contraband worth approximately ¥8 million (less than $8000) was seized. Guard duties were also provided to Kure docks and Tokyo.

The close of 1948 brought with it an end to the major Australian contribution to the military occupation of Japan. The conduct and success of the occupation leading to the emergence of modern Japan was unique in history and a tribute to all involved, and particularly to the administration of General MacArthur. From an Australian viewpoint, these events have never been adequately recorded and/or recognised. The commitment was a significant event in Australia’s postwar foreign relations at a time of very active involvement in world affairs.

It also had significant implications for the development of the regular army in Australia. The commitment to BCOF meant that Australian forces were maintained on ‘active service’ from the conclusion of the war, thus allowing the nucleus of the Australian Regular Army to develop and become established, albeit outside of mainland Australia. The basis of the current regular army was therefore laid directly on the experience and knowledge of men who had served through the war, whether originally enlisting as a part of the Permanent Military Forces (PMF), the Australian Imperial Force or the Citizen Military Forces, and who had then volunteered for service in Japan. The traditions and experience were duly passed on and embodied in the Australian Regular Army, which was now established, and increasingly officered by men trained at the Royal Military College, thus making a significant break with the traditional role of the PMF. The Australian component of BCOF, particularly the 34th Australian Infantry Brigade, established from the wartime forces, carried on the traditions and standards that had come to be expected of Australian forces. It was shown to be disciplined and highly professional in the performance of its occupation duties.