3 Formation of the Royal Australian Regiment Australia and Japan, 1948–50

Wayne Klintworth

Development of the Postwar Army

The dramatic experiences of the Pacific war and the victory over Japan had a fundamental influence upon Australia’s postwar defence and foreign policies. For both the Chifley government and, after December 1949, the Menzies government, the motivations for postwar defence and foreign policies were similar. They considered Australia’s interests would be secured by ensuring that the military potential of Japan was totally eliminated, they supported the United Nations Organisation in its peacekeeping role and attempted to establish regional defence arrangements with powerful allies. These were the main issues in the continuing search for security after 1945. The main difference between the two governments was that Menzies was less confident in the effectiveness of the United Nations to keep peace. His government was to place greater faith in the development of close alliances with Britain and particularly with the United States.

The development of Australia’s defence forces and policies between 1945 and 1950 is discussed elsewhere, but in summary this was a slow response to the changing circumstances and relationships with which Australia was presented.1 It was a period of increasing uncertainty as the regional power structure was being transformed due to an intensifying Cold War confrontation. By September 1950 Menzies was solemnly warning Australians of the possibility of a third world war with ‘our sinister opponent’.2 Yet after having had a substantial field army in 1945 and a major change in the organisation of its defence forces in 1946–47, events were to prove that Australia’s defences were run-down and poorly prepared in June 1950.

Both the Labor government, and the Liberal-Country Party government which succeeded it, acknowledged the requirement for strong defence forces and the need for an ‘advanced state’ of readiness. Traditionally, volunteer expeditionary forces had been raised in Australia to fulfil imperial commitments. In this way Australian contingents had served in the Sudan campaign, the South African War and the First World War. The 2nd Australian Imperial Force (AIF) had been raised in similar fashion in 1939. The capability of Australia’s defence forces prior to the war, therefore, depended upon there being sufficient advance warning of a threat to allow the necessary build-up and training of the Citizen Military Forces (CMF). In 1938 the strength of the Australian Army was 35,157 CMF and 2586 Permanent Military Forces (PMF), neither of which could be compelled to serve overseas. The PMF were mostly employed on fixed coastal defences or as cadre and specialist staff with the CMF. The Defence Act had also specifically excluded infantry from those units which could be raised in peacetime.

The rapid advance of the Japanese in 1941–42 seriously threatened Australia’s interests and for the first time raised the possibility of an invasion of Australian soil. It was a situation that Australia, initially without the assistance of a major ally, found itself ill-prepared to meet alone. The experience of the war had shown the inadequacy of defence preparations based on being given ‘adequate’ warning and the provision of volunteer forces to serve overseas.

The first plan presented for the organisation and composition of the postwar army was produced by the General Staff in 1946. The plan was based on the need to raise five standard divisions in the first year of a war, and required a PMF strength of 34,000 men in two brigade groups and one armoured regiment. Cadre staff for the CMF, staff for headquarters and fixed establishments were included. The CMF strength was to be 42,000 men maintained by a national service scheme. The 1946 plan was rejected in March 1947 because its annual cost was estimated at £90 million and because of strong objections within the Labor government to national service. The government directed that the plan be reconsidered on the basis that only £50 million annually would be available. The Defence Committee subsequently advised the services that they each should plan on £12.5 million per year and that the postwar army should be raised on an entirely voluntary basis. The committee directed that Australia’s defence effort in the interim would be to maintain the strength and organisation necessary, with existing weapons, to provide for the commitment to BCOF, for forces on the mainland for administrative purposes, and ‘to carry forward the organisation of the peace time forces’.3 When hostilities ended on 15 August 1945, Australia had an army of 398,594 men. More than half of these men were overseas, mainly in the South West Pacific area and Borneo. Included in this army were members who had enlisted in the prewar PMF, the AIF and the CMF. They were known collectively as the Australian Military Forces (AMF). Demobilisation of the wartime army began on 1 October 1945 and by the time it ended on 15 February 1947 a total of 349,964 members had been discharged. Because of the considerations of the nature of the postwar army and as a stop-gap measure, it was decided to adopt a non-permanent organisation known as the Interim Army. The Interim Army included all members of the AMF serving on continuous full-time duty on 1 October 1945 and all who joined after that date. Recruiting for the Interim Army began on 15 February 1946. This development was essential in view of the rapid demobilisation and high wastage rate if the army was to meet its postwar commitments, particularly to BCOF. By 15 February 1947 the strength of the Interim Army was 36,790, including 10,436 new recruits who had enlisted for a two-year engagement.4 The consideration and debate on Australia’s postwar defence forces in 1946–47 culminated in the decision to establish a regular army field force and to reintroduce the CMF as the basis for wartime expansion. While both the Chifley and Menzies governments intended to make ‘full and adequate provision for post war defence’, it was apparent that this had to be based on the prewar concept of large reserves supported by a small regular army. The plan adopted in 1947 gave first priority to the establishment of the CMF field force and then the PMF cadre to train them.

The national service scheme announced in July 1950 was primarily intended to add to Australia’s defence preparedness by ensuring that in the event of an ‘emergency’ trained men would be available within the first few weeks of a war.

The regular defence forces established in 1947 were immediately confronted with the realities of peacetime financial restrictions and a national manpower shortage.

Demobilisation and economic reconstruction would be the main concerns of the government at the time. The result, however, was that the large commitment to the BCOF and then to the national service scheme in 1951 worked to reduce the operational capability of the army at a time of heightened international tensions.

The commitments to the BCOF and particularly to the Korean War were to be more notable for the quality of the Australian forces rather than the quantity. By 1950 the army was struggling to maintain one full battalion in operational readiness.

The plan for the postwar defence forces was approved by the government and announced by the minister on 4 June 1947. The program covered the period 1947– 48 to 1951–52, and was to cost no more than £250 million or an annual average of £50 million. Subsequently, financial provision for the program was increased to a total of £295 million because of rising costs. The PMF was to consist of one independent brigade group (including three infantry battalions and an armoured regiment), fixed establishments and CMF cadre staff. The CMF was to consist of two infantry divisions, one armoured brigade group, selected corps troops and fixed establishments. The total strength of the army was to be 69,000 men including 19,000 PMF and 50,000 CMF. Enlistment to both the PMF and CMF was to be voluntary, with recruiting beginning for the PMF almost immediately. Enlistments into the postwar CMF began for the first time in July 1948.

Recruiting was far from successful for both the Australian Regular Army and the CMF. The term ‘Permanent Military Forces’ had become a misnomer in view of the new engagement periods adopted for the postwar army. Use of the term ‘regular army’ was recommended by the Military Board and approved by the Minister for the Army on 13 September 1947. The PMF subsequently became known as the Australian Regular Army or ARA.5 By the end of 1947 it was apparent that the flow of recruits would not meet ARA requirements. The poor recruiting meant that enlistments for all services were not keeping pace with wastage and the inability to achieve manpower targets led to significant underspending. The shortage was keenly felt by the Australian component of BCOF. The supply of reinforcements to the units with BCOF in 1948 was so low that the battalions of 34th Brigade were reduced to barely a third of their full strength by the middle of 1948. They were able to carry out their tasks only because the nature of the occupation duties now required fewer men.

Although the ultimate strength of the ARA was to be 19,000 men, including a field force brigade of over 3000 infantry soldiers, on 12 October 1949 the Minister for Army, Cyril Chambers, confirmed that there were only 1000 infantrymen in the entire army.6 Most of them were at that time located in Japan. In an attempt to retain the services of experienced serving NCOs and tradesmen the Regular Army Special Reserve (RASR) was established in April 1948 to recruit members who did not want to undertake a six-year engagement with the ARA. When the RASR ceased recruiting in November 1948 a total of 5483 men had enlisted.

The manpower situation did not improve and by October 1949 the total ARA strength had fallen to 14,850 while the target strength for the year had risen to 17,000. Included in the actual ARA strength were members of the RASR and Interim Army, both of which were dwindling towards extinction. At this time the Military Board recommended that recruits be sought in the United Kingdom. The proposal was not supported by the Chifley government but was accepted by the new Menzies government in early 1950. Recruiting in Britain began in August 1950. By 25 June 1950, when the Korean War began, the strength of the ARA, including RASR and Interim Army members, was only 14,651.7

Manpower difficulties and financial limitations were dictating the development of the postwar army. By June 1950 the army had not achieved the operational capacity intended by the 1947 plan. Although subsequent events justified the decision to form an ARA field force, government complacency thereafter ensured that financial restrictions rather than strategic priorities directed development. The most immediate implication was that Australia in effect did not have the forces available to meet the type of contingencies likely to arise.8 The Korean War found Australia remarkably unprepared; however, it was fortuitous that the major part of the army field force was on duty in Japan when it broke out.

The basis of the postwar regular army accepted in 1947 was the infantry brigade then located in Japan. When the decision was taken to withdraw two of the battalions in 1948, attention turned to the status and designation of the ARA battalions.

After consulting the commanding officers, Brigadier Hopkins sought to have the matter settled before the two battalions arrived back in Australia. Concerned that despite the unit prestige and regimental spirit developed since October 1945, it would be undesirable to have the ARA units the highest numbered, without battle honours or colours, and with precedence after militia units, he recommended the adoption of designations of CMF units that had not been raised when the CMF was re-formed. It was therefore proposed that the 65th Battalion be designated the 1st Infantry Battalion, City of Sydney’s Own Regiment; the 66th Battalion, the 1st Infantry Battalion, Royal Melbourne Regiment; and the 67th Battalion, the 1st Infantry Battalion, the Oxley Regiment.

The infantry cell within the Directorate of Staff Duties (the predecessor of the Directorate of Infantry) submitted an alternative proposal. With the planned 1949 royal visit in mind it was suggested that it would be appropriate for the 65th Battalion to become the 1st Battalion, King George VI’s Australian Rifle Regiment; the 66th Battalion, the 1st Battalion, Queen Elizabeth’s Australian Foot-guards; and the 67th Battalion, the 1st Battalion, Princess Margaret’s Australian Infantry Regiment.9 Ultimately it was decided to adopt a regimental system, along the lines of the British Army, and the existing units were to be numbered sequentially as a part of one regiment. The three battalions in Japan were designated the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the Australian Regiment (AR) with application made for a royal title.

This redesignation was approved by the minister and took effect on 23 November 1948. The title ‘Royal’, granted by His Majesty King George VI, was announced on 10 March 1949. The Royal Australian Regiment (RAR) thus came into being as Australia’s first regular regiment of infantry. Regimental colours were subsequently presented to the battalions and in accordance with its new status the regiment did not adopt any existing battle honours. The regiment now had the task of establishing its own traditions and was very soon to win its own honours.10 The design of the regimental badge was selected from a number of suggestions considered by the Director of Infantry, Brigadier I.R. Campbell, in early 1949.11

The design was drawn up by Sergeant E.J. O’Sullivan of the 1 RAR intelligence section and had originally been intended for 1 RAR only. The design featured the kangaroo and wattle wreath as distinctly Australian symbols; the boomerang, which had been used in the tactical signs of the 2nd AIF from which the original units of the 34th Brigade were raised; the crossed rifles signifying the personal weapon of the infantryman; and the crown because of the royal title of the regiment. Major K.B. Thomas of 1 RAR suggested the simple but highly appropriate motto ‘Duty First’. This motto was adopted and included on the badge. Although the badge was reproduced on Christmas cards in 1949, it was not until early 1954 that the new hat badge was issued to replace the Rising Sun badge.

The 65th and 66th Battalions arrived back in Australia on 21 December 1948 as the 1st and 2nd Battalions respectively of the AR; from 10 March they were to become the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the RAR. There was little time to notice or celebrate the changes of designation. They were acknowledged at the time by the members, many of whom had served in the AIF, and who were now proud to be part of the first regular infantry battalions of the army. 1 AR moved into barracks at Ingleburn, New South Wales, while 2 AR went to Puckapunyal, Victoria. Because many members of both battalions had remained in Japan with 3 AR, and because of the large numbers of personnel discharged on arrival home, the unit strengths were very low. 1 AR had departed from Japan with a strength for little more than one rifle company with elements of Battalion Headquarters and Headquarters Company.

When Lieutenant Colonel C.A.E. Fraser took command of 2 AR on 11 January 1949 the battalion consisted of about 80 all ranks. Rebuilding the battalions began immediately and by March 1949 2 AR consisted of ten officers and 200 other ranks.12 With such limited manning the battalion organisation included only a headquarters, headquarters company and one rifle company. The lack of other rank personnel and the requirements for routine camp duties and ceremonial guards, such as at Victoria Barracks in Sydney, meant that unit training over the next eighteen months was not possible. Officer and NCO training was conducted, as were range practices at Greenhills, near Holsworthy, along with some specialist weapons training. In May 1949, however, a new training responsibility was given to the battalions. With the closure of the Recruit Training Battalion at Greta, recruit training companies were established within the battalions. Captain C.D. Kayler-Thompson formed the 1st Recruit Training Company at Ingleburn and Captain F. Ahearn formed the 2nd Recruit Training Company at Puckapunyal. These companies were responsible for training army recruits during a twelve-week course before they went to their corps schools for further training.13 The reduced strengths were not the only difficulties confronting the battalions in Australia. Another was the need to rebuild unit esprit de corps. Between the original members who returned from Japan and increasingly, those new recruits who began arriving in 1949, there was initial resentment and friction that had to be overcome. There was also a requirement to re-establish the reputation and cohesion of the battalions. The ‘BCOF mob’ were resented, believed to be riddled with venereal disease and spoiled by an ‘easy life’ in Japan.14 The state of the accommodation and facilities provided were poor. The barracks at Ingleburn were ‘temporary wartime, wooden constructions, unlined and cold in winter and hot and dusty in summer . . . There were very few married quarters . . . (which) resulted in the loss of some good soldiers . . . There seemed to be a constant shortage of funds for urgent works. There were long delays in building repairs, and in providing security for Q stores and the transport compound . . . The filling of holes in the sealed road through the lines was regarded as a major achievement.’15 It was even reported that the 2 AR advance party survived at Puckapunyal by shooting rabbits while 1 AR regimental funds had to assist with the provision of basic items such as toilet paper. The circumstances that the two battalions found themselves in at this time were not happy, particularly coming so close after the occupation duties in Japan.

On 22 March the redesignated 1 RAR had the distinction of mounting the first guard by a regular Australian infantry battalion in Australia when a guard of honour was mounted at Victoria Barracks in Sydney for Lieutenant General Sir John Northcott, Governor of New South Wales. 2 RAR made its first public appearance in Australia when a guard of honour was provided for the Anzac Day ceremony in the town of Seymour near Puckapunyal. On 6 May command of 1 RAR passed to Lieutenant Colonel J.L.A. Kelly.

Battalion activities were interrupted by the coal strike, which began in New South Wales on 27 June 1949. The decision of the Chifley Labor government to use ARA soldiers to break the nationwide strike was an historic political and industrial event. On 12 July, by Cabinet direction, army began organising to assist in the transportation of coal in New South Wales and Victoria. On 27 July, when attention was focused on the New South Wales coalfields, Operation Excavate was initiated.

A special force of 2800 men had been organised and was deployed to begin mining operations at 0001 hours on 2 August 1949. The army force consisted primarily of men from the corps of Royal Australian Engineers (RAE), Royal Australian Army Service Corps (RAASC), and the Royal Australian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (RAEME). The force was employed working the open-cut northern mines around Muswellbrook (Norforce) and the western mines around Marangaroo (Wesforce). Their total output for the thirteen-day operation was 107,188 tonnes of coal. Included among the army force was a large security component consisting mainly of infantrymen from 1 and 2 RAR armed with submachine guns and rifles.

They were deployed to the mines to provide guards, escorts, cooks and drivers. The 990 men of Norforce conducted their operations from Muswellbrook and were commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Kelly.16

From the end of 1948 BCOF was maintained solely by Australian forces until it ceased operation with the signing of the Japanese Peace Treaty in San Francisco in September 1951. The successful progress of the occupation and the requirements for their troops elsewhere, particularly in Malaya, had led to the withdrawal of the British after little more than one year. In July 1947, the withdrawal of all Indian Army forces was announced because of the pending constitutional changes that led to Indian independence and partition. Finally, in November 1948, the last of the New Zealand contingent was withdrawn because of demands for manpower at home. Despite its dwindling strength and the increasing ‘formality’ of its duties, the Australian government persisted in retaining troops in Japan for as long as the occupation continued. The maintenance of the presence of Australian forces in Japan was an exercise of power and prestige; but more important was the postwar foreign policy objective of establishing a secure strategic position for Australia in the Pacific. This search was to be increasingly frustrated as the original terms of surrender were compromised. While Australia still regarded Japan as a potential threat it was becoming clear that the Americans had another purpose.17 The strength of the Australian component of BCOF was to change in 1948. At its meeting on 28 April 1948, the Council of Defence concluded that the Australian component of BCOF should be reduced to one AMF battalion, one RAAF squadron and a naval support unit of one ship, with administrative units to maintain them. The total strength was to be about 2750 men with the reduction being effected by 31 December 1948. Their conclusions were based upon consideration of the state of the demilitarisation of Japan and the reality of the dwindling strength of the army. The Commander-in-Chief, BCOF had advised that an army strength of 5000 was the minimum strength compatible with the original objects of the force. Ultimately the council decided that only a token force would be provided.18 The Menzies government, elected in December 1949, decided to end the contribution to the occupation. It was a decision made against the background of Cold War confrontation which saw the increasing determination of the US to use Japan as a bastion against communism. The government decided to complete the withdrawal of Australian troops by the end of 1950 to reduce the financial and manpower burden of maintaining the force in Japan. The withdrawal would also facilitate the development of the CMF and assist with the implementation of the national service scheme by providing additional manpower resources of the regular army. The outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950 occurred at the time BCOF had been reduced to little more than 2750 men including one understrength battalion. This event at once increased the significance of BCOF, its facilities, command and logistics organisation, and allowed Australia to respond almost immediately with men and equipment to support the United Nations resolution of 27 June 1950.

The main achievements of BCOF included the disarming, demilitarisation and military control of five prefectures of the main island of Honshu, and the whole of the Shikoku in accordance with SCAP Directives; ‘repatriating through ports in its area of 750,000 Japanese “surrendered personnel”’ and other foreign nationals, particularly Koreans; extensive ‘patrolling by air, sea and land to uncover smuggling . . . and black marketing’; and the provision ‘of expert advice on engineering, town planning . . .’ and assistance in reconstruction. At its peak, BCOF controlled 20 million Japanese in an area of 60,000 square kilometres.19

The 3rd Battalion in Japan—1949–50

Despite being seriously undermanned, the burden of the remaining BCOF occupation duties from 1949 fell upon the 3rd Battalion, the Australian Regiment. The battalion was about half strength and was particularly in need of junior officers. The task of building and training the battalion throughout 1949–50 was to be hampered by the lack of reinforcements, the turbulence accompanying discharges and the influx of new personnel, and commitments to occupation duties. Despite this, a core of officers and senior NCOs remained within the battalion and were to make a significant contribution to its spirit. Many, such as the battalion second-in-command, Major Ferguson, and the regimental sergeant major, WO1 J. Harwood, had extensive wartime experience.20 Reinforcements had been arriving from other units returning to Australia but a larger number marched out from the battalion to return to Australia for discharge. This latter group of men belonged mainly to the Interim Army and were due for discharge because their term of enlistment had expired.

Despite the priority given to the rebuilding of the ARA brigade group, particularly the battalion in Japan, the supply of reinforcements remained inadequate. In February 1949, however, 28 reinforcements arrived directly from Australia, the first such reinforcements since October 1947. The pending arrival of fourteen young officers from the 1948 RMC graduation was also eagerly awaited. Most of these young officers were to be the platoon commanders with which the battalion would go to war in eighteen months’ time.21 In May 1950, just prior to the announcement of the proposed withdrawal, the battalion strength totalled only 545 all ranks, including 386 ARA, 92 RASR and 67 Interim Army.22 Occupation tasks required one company to be committed permanently to guard duties in Tokyo, and one company to provide guards at the Kure docks and in Hiro at the Commander-in-Chief’s residence, at the BCOF General Hospital and a unit quarter guard. Plans were prepared for the defence of the Hiro area in case of civil disorder, and troop deployments to crisis points in the prefecture were rehearsed. Fortunately there were to be no serious incidents for the remainder of the occupation, and duties were very much of a routine nature. Responsibilities in Tokyo were reduced after 13 May 1949 when the last allied guard was mounted at the Imperial Palace. Thereafter, the Japanese civil police performed guard duties at the palace. When the new occupation routine and commitments were established attention then focused on reorganisation and training.

Training in 1949 was initially limited to immediate requirements, particularly the training of reinforcements by the Cadre Company. As the reinforcements were distributed within the battalion, A and B Companies were brought to full strength and in April the third rifle company (C) was re-formed. The reorganisation allowed greater flexibility to carry out training by freeing one company at a time from occupation duties. From April, as the weather improved, the companies began rotating through the Haramura training area to conduct six weeks of range practices, assault courses and field training. Despite these efforts collective training often did not progress further than platoon level. At the completion of its training period each company marched the 32 kilometres back to Hiro. Officer training began in April and was conducted every Monday evening. Also in April, a training cadre was established at Haramura to conduct a series of courses to raise the general standards of conduct, knowledge and discipline of NCOs. At the end of the month Lieutenant Colonel Mackay noted in the unit diary the ‘healthy rivalry’ developing between the companies and the rising esprit de corps of the battalion. This was actively fostered during the following months. Unit activities were emphasised, such as the Australians’ participation in the American Independence Day Parade on 4 July reviewed by General MacArthur, along with unit training.

Beginning in August with Exercise Olympic, the battalion began a series of live firing exercises to practise and demonstrate the company in defence and attack. RAAF Mustang fighters of No. 77 Squadron as well as the machine-guns and 3-inch mortars detachments formed from within the battalion provided fire support.23 The new commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel F.S. Walsh, who took over command on 12 August, insisted on unit muster parades each week to further bring the otherwise independent sub-units together as much as possible. A reallocation of duties in December meant that one rifle company, Battalion Headquarters and Headquarters Company would provide the occupation guard duties, allowing the remaining two rifle companies the opportunity to carry out training. The culmination of the training program for 1949 was a battalion bivouac on a number of small, uninhabited islands in the Inland Sea in October.

In the new year training recommenced in February when B Company departed to conduct field training at Haramura. Also in February a small detachment from the battalion escorted a group of 93 Japanese war crimes suspects from Sugamo Prison in Tokyo to Yokohama and then by ship to Manus Island to stand trial. The next two months were dominated by the preparations for and the conduct of the 1950 Gloucester Cup completion. With judges sent from Australia to assess the battalion, 3 RAR was successful in retaining the cup for the second time in succession. Because of subsequent operational commitments this was to be last occasion on which the competition was conducted until 1972.

In February, 3 RAR had three large RAR badges cast out of spent brass shell cases. One of these was placed above the entrance to the barracks at Hiro, while the others were sent to the two battalions of the regiment then in Australia.

In May the bulk of the battalion went to Tokyo for duties and to participate in the ceremonial parades marking Empire Day and the king’s birthday. The visit also provided the opportunity to make use of the range facilities at Camp Palmer. By the time the battalion returned to Hiro at the beginning of June, planning for the unit summer training program was well advanced, but these plans were to be interrupted by the government’s announcement on 11 June that the remaining Australian component of the BCOF would be withdrawn by the end of the year. 3 RAR was to return to Enoggera in Brisbane where new barracks were to be constructed, and preparations for the return to Australia began immediately. The remaining 67 Interim Army members marched out of the battalion to return to Australia and the movement of reinforcements to BCOF was suspended.

The sudden outbreak of war on the Korean peninsula on 25 June altered the immediate plans. On 28 June the government announced that the withdrawal from BCOF was to be delayed and two days later the commitment of Australian air and naval forces to Korea was announced.

The period of the occupation of Japan thus came to an end with the battalion, like the rest of the RAR, under strength, under equipped and collectively poorly prepared for war.

The immediate threat to 3 RAR after the outbreak of war in Korea was from the possibility of North Korean air raids and internal disorder in Japan.24 Plans for air defence and dispersal were prepared and rehearsed; ammunition was issued, LMGs mounted and air sentries posted. With B Company on guard duty in Tokyo and C Company conducting training, most of the early tasks fell to A Company under the command of Captain J.W. Callander. On 3 July a group of fifteen men under Lieutenant D.M. Butler were deployed to guard the cipher office, control tower and ammunition stores at the RAAF Base at Iwakuni. Another group of sixteen men were sent to guard the Japan Oil Storage Company area at Yoshiura near Kure. A third group under Lieutenant R.F. Morison were given eight 20 mm Polsten anti-aircraft guns with which to conduct live firing practices at Haramura. A member of the battalion later wrote:

Within a remarkably short time, nine days in fact, the crews had received a measure of training and had fired at a moving target prepared by the Pioneer Platoon. Their aim it seems might have been too good because one report ruefully says that the target was ‘unfortunately destroyed in the early stages of practice and firing had to be continued against a stationary target’.25

The number of anti-aircraft guns was increased to 21 and after training they and their crews were deployed to Iwakuni RAAF Base. The duties at Iwakuni lasted until the end of the month, during which time the men enjoyed RAAF messing and were thrilled by the sight of RAAF Mustang aircraft taking off and returning from operations against the North Korean forces or escorting American bombers that attacked the Han River bridges.

For most of July the battalion continued in the belief that it would return to Australia from Japan. Lieutenant Colonel Walsh attended a conference at BCOF Headquarters in Kure on 11 July to discuss the proposed accommodation arrangements at Enoggera Camp in Brisbane and the disposal of stores. ‘There were other things too, like a bingo night for the NSW Flood Relief Fund; and inter-company swimming (won by C Company); the threat of typhoon Grace, and the photgraphing of six selected soldiers for ARA recruiting posters. And there were routine orders listing such matters as Japanese shops that were out of bounds, regulations concerning use of bicycles, and the keeping of pets.’26 Meanwhile, Lieutenant General Robertson had warned his superiors in Australia that ‘an urgent call [for troops] may be made to anyone who has anything to offer . . . I know that [MacArthur, then Commander United Nations Forces in Korea] would like Australians and would reason that if he got some he could expect more following his wartime experience.’27 When on 25 July Lieutenant Colonel Walsh attended a conference at HQ BCOF, he learned that Macarthur had indeed requested the use of BCOF forces in Korea. The request was passed immediately to the Chiefs of Staff in Australia, while Robertson directed 3 RAR to prepare to move to Korea pending a reply from Australia.

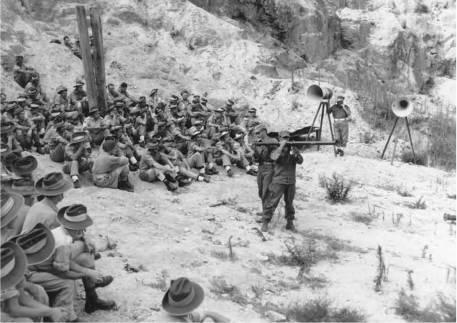

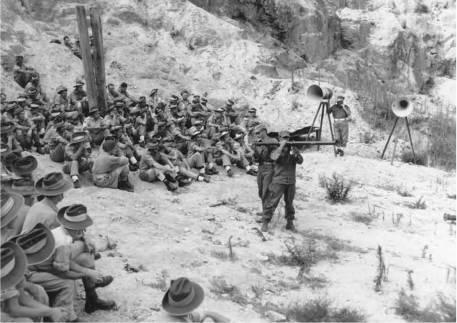

With events deteriorating in Korea 3 RAR was provided with new equipment including US rocket launchers. The photograph shows members of the battalion being instructed on the 2.5-inch Bazooka by a US Army instructional team in August 1950 (AWM photo: Robertson Collection).

Preparations began on 26 July with plans prepared to reinforce the battalion and raise its strength from twenty officers and 530 men to a total war establishment of 39 officers and 971 men. Much of the administrative and organisational work fell to the second-in-command, Major Ferguson. Equipment such as maps, radios, line stores, mortars, medium machine-guns, 3.5-inch Bazookas, Bren gun carriers, motorcycles, 17-pounder anti-tank guns and about three times the existing motor transport had to be obtained. The majority of the men and equipment would have to come from Australia and would take some time to arrive. In the meantime essential guard duties in Tokyo were taken over by those older men for whom it was judged, after much ‘soul-searching’, that the rigours of Korea might prove too severe.

Support Company was a sub-unit most members knew existed only in training pamphlets. A Company was temporarily disbanded to form Support Company, which was raised under Captain A.F.P. Lukyn with the assistance of the newly appointed platoon commanders, Captain D.P. Laughlin (mortars) and WO2 W.A.M. Ryan (medium machine-guns).

At the end of July, members were asked to volunteer for operational service in Korea because as ARA, RASR or Interim Army personnel they had only enlisted for service in Australia and Japan. All but 26 members of the battalion signed on for Korea; those members who did not sign on joined those on guard duties in Tokyo.

At least three members who wished to go to Korea, one the battalion second-in-command, did not sign on, choosing deliberately to ignore what they regarded as a rather ridiculous administrative requirement; the appropriate papers subsequently pursued them around Korea for some months afterwards.

Training began in earnest in August despite the shortages of men and equipment, for it was not known how much time the battalion would have. All band personnel and medical orderlies began a stretcher-bearer’s course, including hygiene and first aid. Exercise Experimental began with C Company moving to Haramura for range practices and company training in delaying tactics. On 4 August the remainder of the battalion, less B Company who were still in Tokyo on guard duties, deployed by marching the 32 kilometres to Haramura to reinforce C Company. The exercise ended on 5 August when C Company completed a withdrawal to rejoin the battalion after the Assault Pioneers had ‘demolished’ a bridge after C Company’s passage across.

The exercise provided valuable experience in the layout of Battalion Headquarters, the issue of orders, water discipline, road movement and the operation of both the F and B Echelons. The whole battalion, now including B Company, exercised on 10–11 August in the Gobara area occupying defensive positions. Between the battalion training activities, the companies conducted their own training exercises emphasising attack and defence.

The battalion situation in August was still far from satisfactory in view of the rapidly deteriorating events on the Korean peninsula. The task of developing the battalion into a fighting force was taken extremely seriously and conducted with urgency by all involved. Although reinforcements from Australia were still awaited, major equipment such as radios and rocket launchers had begun arriving, mostly from US Army stores. Inoculations against cholera were made and anti-malarial tablets distributed. Motor transport began to arrive in mid-August, and altogether the battalion received 56 jeeps and 26 trucks. The jeeps were provided in place of the Bren gun carriers with which the battalion should have been equipped.

On his return trip to Australia in August 1950 the Prime Minister, Mr Menzies, visited Japan and addressed 3 RAR on their task in Korea. The photograph shows the Prime Minister inspecting a 3 RAR guard of honour. Left to Right, Lieutenant J.M. Church, Captain W.M. Stone, Corporal J.D. Parsons, Private A.T. Gallaher, Mr Menzies, and Private H.C. Lyon (AWM photo no. 146500).

In late August the battalion prepared to conduct a unit exercise in the Sambehara area. B Echelon was deployed on 22 August when later that morning the exercise was suddenly cancelled by Headquarters BCOF. The situation in Korea was such that the battalion was ordered to concentrate in Hiro and given a warning order to be prepared to move to Korea at first light on 25 August.

The situation in Korea had become so serious around the Pusan perimeter that the British government had decided to send the 27th Infantry Brigade, then on garrison duties in Hong Kong, to support the US Eighth Army in Korea. This brigade, under the command of Brigadier B.A. Coad, was under strength and consisted of two battalions: the 1st Battalion, the Middlesex Regiment and the 1st Battalion, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

The announcement by the British government prompted the Australian Acting Prime Minister, Arthur Fadden, to offer to place 3 RAR under command of 27th Brigade to bring the brigade up to its operational level of three battalions and thus form a Commonwealth brigade. The offer was accepted and the battalion frantically started making preparations and completed packing on 23 and 24 August. Additional cold weather clothing was issued (underclothing and leather jerkins), inoculations completed and attachments marched in. The move, however, did not eventuate as the view of the Defence Committee did not support the immediate commitment and on 26 August the battalion was advised that it was to remain in Japan until it was brought up to strength and had received all essential stores and equipment.

On being stood down, the battalion returned to intensive sub-unit and specialist platoon training. Colonel Walsh noted:

Company field training consisted in the main of exercises on the advance, encounter battle, the attack, defence on a wide and narrow front, counter attack, withdrawal and relief in the line, also the maintenance of direction, movement over rough country and occupation of high features at night . . . In addition all companies carried out range practices on all weapons and the platoons of Support Company underwent intensive training with their respective specialist equipment.28

Lieutenant Colonel C.H. Green, on exercise with 3 RAR in Japan on 15 September 1950, three days after he assumed command of the battalion. He died of wounds on 1 November 1950 while on operations in Korea, the only commanding officer of a battalion of the regiment to die on active service (AWM photo no. 146724).

Reinforcements began to arrive towards the end of August, with the first draft comprising 48 men from 1 RAR under the command of Major A.R. Gordon. The second draft consisted of 29 personnel specially enlisted for services in Korea (K Force enlistees). Recruiting for Korea had began on 7 August for the one thousand men required to serve for three years. Finding recruits was not difficult as young men and many others with wartime experience sought to join up.

Over the next two weeks, the battalion received 22 officers and 450 reinforcements or replacements.29 Later drafts included men who had volunteered from 2 RAR. By the end of August the battalion strength was 582 all ranks. This reinforcement enabled A and D Companies to be re-established in early September, mainly with ‘K Force’ volunteers. The rapid influx of reinforcements and replacements rebuilt the battalion and also brought with it command changes. The new appointments included the commanding officer, four company commanders, the acting officer commanding Support Company, and the regimental sergeant major. By September the battalion had reached its establishment strength, and other reinforcements who subsequently arrived in Japan were to be held there to form the battalion’s first line reinforcements.

On 12 September Lieutenant Colonel Charles Green, DSO, replaced Lieutenant Colonel Walsh.30 Despite a typhoon and heavy rains, from 13 to 16 September the battalion deployed on Exercise Bolero to Haramura where they occupied defensive positions before conducting a withdrawal back to Hiro. Valuable lessons were learned, particularly with regard to difficulties in the movement of vehicles and the protection of Battalion Headquarters from the elements.

This photograph was ‘Picture of the Week’ in the Women’s Day and Home magazine of 30 October 1950. It shows Australian troops in Japan interrupting their final battle exercise for Korea to allow two civilians to proceed along the road (La Trobe Collection, State Library of Victoria, SHF 052.9 AU 7A).

Final training, between 19 and 23 September, comprised a series of section, platoon and company exercises and demonstrations at Nomingo and Haramura.

During the exercise the battalion received their six 17-pounder anti-tank guns and their prime movers, to replace the 6-pounders. Although cumbersome and heavy, recent American experience had confirmed the need for the guns to deal with the T–34 tanks used by the North Koreans.

On 23 September Lieutenant General Robertson ordered the battalion to return to Hiro and prepare to move to Korea. At 1730 hours that evening, the battalion began the 32-kilometre march to Hiro, the first company arriving at 11.30 pm.

Final preparations for the move entailed the issue of new automatic weapons, ammunition and clothing and equipment, the crating of equipment and stores, preparation of embarkation rolls, loading of vehicles and the packing of personal kit not required in Korea. On 25 September Lieutenant Colonel Green left for Iwakuni where he joined General Robertson. Both flew across to Korea where Green remained to await the arrival of the battalion. A small logistic force, Australian Forces in Korea Maintenance Area (AUSTFIKMA) had already been established in Pusan to support the battalion from the time it arrived.

The loading of stores into the USS Aiken Victory began at 7.00 pm on 25 September and continued until 27 September. Embarkation of the battalion began at midday on 27 September and was completed by 4.00 pm. After a special order of the day from the Chief of the General Staff, Lieutenant General S.F. Rowell, was read to all ranks, they were addressed by Lieutenant General Robertson. The Aiken Victory sailed at 7.45 pm and was farewelled by a large number of BCOF personnel and dependants, and some curious Japanese. The intelligence officer recalled that the

[B]attalion which sailed that evening had a wealth of individual experience in it, many of its soldiers had World War Two experience and on average were older than those in today’s battalions. Many NCOs wore ribbons and all majors and captains (excluding the RMO) had served in World War Two. Of the twelve rifle platoon commanders, however, only one had been on active service.31

The battalion, fully equipped and at full strength, was off to war.