5 The Malayan Emergency Malaya, 1955–60

Jim Dolan

The commitment of an Australian infantry battalion to operations against the communist terrorists in Malaya in October 1955 was only partly related to events in Malaya. The Malayan Emergency had been under way since 1948, and in 1950 Australia had committed RAAF units.1 Initially Australia had resisted sending ground troops and the outbreak of the Korean War had made such a commitment impossible without conscription. By October 1954, when, following the decision of the US to reduce its commitment Australia withdrew 3 RAR from Korea, the British were clearly winning their war in Malaya. An Australian infantry commitment to this new theatre would be useful but not crucial. However, the communist victory in North Vietnam in 1954, closely following the armistice in Korea, seemed to offer communist China the opportunity for further aggression in South-East Asia. In response, efforts were undertaken to provide for collective security against this threat, and on 8 September 1954, the Australian Minister for External Affairs, Richard Casey, signed the South-East Asia Collective Defence Treaty, soon to be known by the organisation it set up, SEATO.

As early as 1952, under the auspices of ANZAM, the British had raised the possibility of creating a Far East strategic reserve and the formation of SEATO in 1954 seemed to provide the umbrella for creating such a force.2 Established soon after the Second World War, ANZAM was an informal Commonwealth arrangement based on the common defence interests of Australia, New Zealand and Britain in South-East Asia and the South-West Pacific. The ANZAM Defence Committee was chaired by the Secretary of the Australian Department of Defence and included the Australian Chiefs of Staff and the Chiefs of Defence Staffs of New Zealand and Britain. Throughout 1954 the ANZAM staff worked on plans for the British Commonwealth Far East Strategic Reserve (BCFESR) and in October 1954 Australia agreed in principle to the establishment of the force.

At the Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Conference in London in January 1955 it was decided to establish the BCFESR and Australia undertook to contribute two destroyers or frigates, an aircraft carrier on an annual visit, additional ships in an emergency, an infantry battalion with supporting arms, a fighter air wing of two squadrons, a bomber wing of one squadron and an airfield construction squadron.

But while Australia had agreed to contribute forces to Malaya, it had not yet decided whether these would be used against the communist terrorists.3 The ANZAM Defence Committee met on 26 April 1955 to produce a draft directive for the BCFESR and on 15 June the Australian Cabinet met with the Chiefs of Staff to consider this and other aspects of the commitment. It was agreed that the primary role of the reserve was to ‘provide a deterrent to, and be available at short notice to assist in countering, further communist aggression in South East Asia’. At the discretion of the Commander-in-Chief, Far East, the BCFESR could be employed in defensive operations in the event of any armed attack on Malaya or Singapore. Its secondary role was to assist in the maintenance of the security of Malaya by participating in operations against the communist terrorists so long as this did not prejudice the readiness of the reserve to perform its main role. However, this did not extend to use in civil disturbances or other internal matters in Singapore or Malaya. Indeed the possibility of disturbances in Singapore meant that it was necessary that a British battalion be stationed there and Cabinet decided the army component would go to Penang Island at first and later to Malacca.4 The land component of the BCFESR was to consist primarily of the resurrected 28th Commonwealth Infantry Brigade Group that had operated during the Korean War as part of the 1st Commonwealth Division. Disbanded in Korea in 1954, it was re-formed at Penang the following year and consisted of Australian, British and New Zealand battalions, each with their supporting elements, and an initially British commanded integrated headquarters. While the Australian battalion commander was under operational control of this British commander, he had the ‘right of appeal’ through the Commander, Australian Army Forces, Far East Land Forces, in Singapore to the Australian government, if need be.

An Outline of the Malayan Emergency

Despite the SEATO role of the BCFESR, there is no doubt that the Australian government expected that its forces would be involved in counter-terrorist operations and it is necessary to provide some background to the Malayan Emergency. The roots of the Emergency lay in the formation of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) in 1927. When the Japanese occupied the Malayan peninsula in 1942 the communists were one of the few groups able to be armed and organised by the Allies into a guerilla force. Chin Peng, the Secretary-General of the Communist Party of Malaya during the period of the Emergency, worked with the wartime guerilla groups and for his activities was awarded the OBE and participated in the Victory March in London in 1946.

Postwar Malaya was a racially divided community and the communists skilfully exploited the tensions between the Malay, Chinese and Indian communities. The MCP was essentially a Chinese movement but to widen its appeal the fighting arm was called the Malayan Races Liberation Army (MRLA). In 1948 this organisation numbered approximately 4500 active members armed with British weapons supplied during the Japanese occupation. Supporting the fighting arm was the Min Yuen, or ‘masses movement’, a supply and intelligence organisation in the villages and the cities numbering, perhaps, half a million persons who were the eyes, ears, hands and feet of the army.5 The MCP plans to establish a Soviet state had followed communist revolutionary doctrine, and the Japanese occupation had only caused them a brief pause. They accelerated their plans after the Second World War, and a state of emergency was declared in 1948 as the result of the murder of a group of white rubber planters at Sungei Siput in Perak state (see map 5). The Emergency Regulations, which the state of emergency brought into being, were special laws covering such activities as possession of firearms, powers of arrest and detention, control of foodstuffs and clearing of undergrowth.

The initial reaction of the security forces, a term used to cover both army and police units, was to conduct ineffective large unit operations. Eventually small unit patrols were introduced, and with few exceptions, this became the method of operation for the rest of the Emergency. Control of the population was essential and in Malaya this was undertaken by the resettlement of 423,000 isolated Chinese ‘squatters’ from their homes on the jungle fringe, where they were susceptible to communist influence, to 400 New Villages where their movement could be controlled. Begun in 1951 this took eighteen months to complete. In the early stages of the Emergency, the communist terrorists (or ‘CTs’) were able to operate in groups up to 200 strong but by the end of 1951 the resettlements and small unit operations based on an extensive intelligence effort had generally reduced them to operations involving groups of no more than 20 to 30 people.6 By 1954, two-thirds of the guerillas had been eliminated and the murder rate was down from 100 per month in the early years, to 20 per month.7 In 1953 the first ‘white area’, an area declared free from Emergency Regulations due to the low level or eradication of communist threat, had been declared. By 1956 most of eastern Malaya had been declared white and troops were redeployed to concentrate on the ‘blacker’ areas.

By 1957 there were thirteen overseas battalions (five British, six Gurkha, one New Zealand, and one Australian) in addition to eight Malay battalions and a police field force of approximately 3000 members. Nine years of war had reduced the fighting component of the MCP from a peak of 8000 in 1951 to about 2000 members. This force was concentrated in the southern state of Johore (approximately 500), in the north-western state of Perak (about 500), in the Betong salient in Thailand (about 200) and with the remainder in small, scattered groups throughout the peninsula. A measure of the effectiveness of counterinsurgency operations to this time was that the main preoccupation of these groups was searching for food.8 In the mid-1950s, Malaya was in the last stages of colonial government. The supreme commander of all land, sea and air forces in 1951 and 1952, General Sir Gerald Templer, saw the fighting of the war and civil running of the country as ‘completely and utterly interrelated’. The war in Malaya during the Emergency was notable for the high level of cooperation between the three arms of government: civil, police and military, at every level. Malaya was divided into states and the states were further divided into districts. When the Australians first arrived the federation had a high commissioner (the Governor) and each state was ruled by a Malay sultan aided by a number of British and Malay officials, and the district officers were British.9 However, it was an integral part of the war strategy that independence would be granted to Malaya as soon as possible.

The most obvious manifestation of the civil control of the war was the State and District War Executive Committees (SWEC and DWEC). The chairman of the committee in each case was the senior administrator, the state prime minister or the district officer. Members of the committee were the police and military commanders of local forces, and community leaders such as business or racial representatives.

In the case of a SWEC, the resident brigade commander was a member and the commander of the battalion permanently allocated to a district sat on the DWEC.

The full committee met weekly but an operations subcommittee consisting of, for example, the commanding officer of the resident battalion, his operations and intelligence staff, the police commander and the local Special Branch officer met daily. This meant that all parties were continually informed and that any intelligence could be acted on immediately.

The geography of the area in the north-west of the peninsula where the battalions of the Royal Australian Regiment were to operate consisted of a coastal strip of predominately rice paddy cultivation inhabited almost entirely by Malays. Inland were a number of cultivated valleys where the rubber estates, the tin mines and the tapioca plantations were worked predominantly by Chinese and Indians living either in rubber estate ‘lines’ or in ‘new villages’. Towards the centre of the peninsula were areas of dense mountainous jungle inhabited by aborigines in isolated settlements, not far from the Thai border. Apart from three frontier posts in cultivated land, most of this area consisted of dense mountainous jungle stretching for kilometres on either side. This area was a sanctuary for Chin Peng and several hundred of his hard-core guerillas whom he held as a reserve force for the Central Committee of the MCP.

Life in the New Villages, with populations of between 500 and 1000 persons, was governed by a strict curfew which required all villagers to be out of the rubber plantations by 4.00 pm, to be inside the village area between 6.00 pm and 6.30 pm, and to be inside their houses between 10.00 pm and 5.30 am. The Emergency

MAP 5: North-West Malaya. This map shows the Malayan states of Kedah and Perak, where the Australian bat talions generally operated during the Malayan Emergency. The Australian battalions were based on Penang Island. Company rotations to the RAAF base at Butterworth were maintained exclusively by the regiment for many years.

Regulations also strictly rationed rice that was delivered to the shopkeepers by escorted convoys and for which each shopkeeper had to account. The stringency of the regulations meant that tinned food had to be opened in the shop so that it could not be stored and smuggled to the communists, and workers on their way to the plantations were subjected to strict searches. Only the aboriginal inhabitants of the deep jungle who lived in small settlements in the most isolated areas, sometimes three or four days’ walk away from the populated river valleys, avoided these regulations. Because of their susceptibility to terrorist influence and their potential as a food source for the communists the government located police camps, or ‘forts’, in the midst of the aboriginal villages.10

Jungle Patrolling—2 RAR in Malaya

This was the situation in Malaya when 2 RAR left Australia in the MV Georgic as the major component of a 1400-man force, arriving in Malaya on 19 October 1955. The ship docked the next day and the unit was transported to its new home, Minden Barracks, in the foothills on the eastern side of Penang Island. Because of long periods spent on operations, Minden Barracks was only the nominal home of the three RAR battalions that served in Malaya during the Emergency. It was, however, normally the location of the rear echelon, including a family liaison officer and his staff, and a security force.

The commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel James Ochiltree, aged 36, was a Duntroon graduate who had served in the Middle East, New Guinea and in the occupation force in Japan. His RSM was WO1 W. Mills.

With a strength of 35 officers and 739 soldiers, the battalion was conventionally organised for counterinsurgency operations with four rifle companies each of three platoons, a support company with signals, assault pioneer, mortar (3-inch) and medium machine-gun (Vickers) platoons, and a headquarters company.11 The soldiers were armed with the Bren light machine-gun, the No. 5 (Lee-Enfield) .303 rifle (which was issued to replace the No. 1 rifle after arrival in Malaya) and the Owen machine carbine. Forward scouts were armed with five-round magazine shotguns and platoon commanders were given the low muzzle velocity M1 carbine, possibly, as one platoon commander later noted, ‘to encourage [them] to command their platoons and to discourage them from getting involved in any fire-fights . . .’.

In 1956 the FN rifle was provided on a scale of one per section for familiarisation, with subsequent battalions being fully equipped with the SLR.12 Some families accompanied the battalions on the troopships but most arrived by sea or air in the next few months—though a few families did not sail from Australia until June 1956. Apart from a number of hired quarters in the outskirts of Georgetown, most were assigned newly acquired married quarters at the Tanjong Tokong Estate on the coast north of Georgetown. Apart from the separations, most memories of family life were pleasant. Those with families were provided with furnished bungalows on Penang Island and the local government paid for amahs (two for officers, one for ORs). One platoon commander recalled that as a result married men sometimes ‘found it hard to adjust to a pattern of weeks on patrol interspersed with bouts of pampered living’. Single men could also go to Penang or Ipoh but had to remember that the ‘main towns and their “out of bounds” areas [were] patrolled by British–Australian military police patrols’.13 Following an acclimatisation period of about three weeks sub-units of 2 RAR were deployed to training areas on the island of Penang. Small numbers of terrorists were known to be operating in these areas so everyone carried live rounds and NCOs had magazines on their weapons. While the battalion trained under the company and platoon commanders, the commanding officer and his staff made a series of visits to familiarise themselves with the operational situation. Administration would prove challenging as the battalion was to be supplied through the British supply system which the Australians were not familiar with.

The commanding officer was keen to have the battalion in operations as soon as possible and in late November the battalion prepared for Operation Kedah, but this was cancelled and the battalion instead used the period for training. In early December the battalion was again ordered to prepare for operations in the Jeniang region, but this was also cancelled. On 28 December, however, Lieutenant Colonel Ochiltree returned from a conference at brigade headquarters with orders for Operation Deuce, the first of a series of operations that was to keep the battalion active for the next two years.

Operations in which 2 RAR and the subsequent battalions took part were concentrated in the north-west of the Malayan peninsula, in the tin and rubber producing river valleys of Perak, and the mountainous jungles of Perak and Kedah. The type of operation was a reflection of a strategy decided on in 1954, which was to concentrate initially on the areas where communist influence was weakest, that is, the eastern and central parts of the peninsula where the Chinese were fewest. Having substantially reduced or eradicated communist influence from these areas, resources could then be allocated to areas in the rubber and tin states astride the road and railway on the western side of the mountains.

Operations conducted in Malaya were generally of two types. Routine activities carried out by every resident battalion in each district were known as ‘framework operations’. Operations that concentrated larger forces in the worst areas, and which took about six months to prepare for, were known as ‘Federal priority operations’.

Watched by the crew of an armoured car which escorted their vehicles to the jumping-off spot, diggers from the ‘stand-by’ platoon from B Company, 2 RAR head off through a rubber plantation on the trail of a recently sighted gang of communist terrorists. For 24 hours they had been ready to move, awaiting the word to ‘saddle up’. Front right is Corporal Wally Thompson, later to be the first RSM of the Army (AWM photo no. HOB/751/MC).

The district chosen for the operation, which would normally have had one resident infantry battalion, saw no increase in troops in this early stage but an increase in police Special Branch officers in order to improve the flow of intelligence. The resident battalion would then work to reduce food supplies to the guerillas and then the operation would begin. A brigade-sized force would join the original battalion and with the use of cordons and rice rationing further pressure was put on the guerillas to force them to move. Guerillas on the move were highly vulnerable both to a chance encounter on a jungle path and to the discovery of a camp. It was generally considered that the most effective way to inflict casualties was to locate an enemy jungle camp without being seen, to deploy ambush parties on surrounding tracks and then to launch a small but determined assault.

In either type of operation a battalion’s resources could be stretched. The resident battalion in each district would establish three or four company-sized bases. At any one time the battalion could have four or five platoons (sometimes more) living in the jungle, each for two to four weeks at a time, listening and watching for movement or signs of the enemy’s presence. Other platoons patrolled the rubber estates, checking passes and watching for anything unusual. After the rubber curfew at 4.00 pm, half a dozen ambush parties moved out onto likely enemy tracks.

Supporting these operations were the police posts of ten or twelve Malay constables in each Chinese village and the locally recruited Home Guard of about 35 men in each village, of which five were normally on duty each night.

Patrolling in the jungle was often geared to looking for any sign of recent terrorist activity such as recent use of tracks, or a vine wrapped around a tree that may indicate the nearby presence of a food dump. From the company base, platoons were sent out and the platoon commander would set up a platoon base from which his sections would then patrol. It was necessary to be so thorough in searching jungle for signs of the enemy that one platoon could search only a thousand square metres daily.14 Patrolling in primary or secondary jungle in the tropics was exhausting and to maintain the high standards of necessary battle discipline in such terrain and in such an enervating climate was a test of leadership.15 Ambushing was the most demanding form of jungle activity and for the individual ‘it meant hours of lying motionless and alert to respond instantly’.

However, the enemy was not the only hazard. One ambush was compromised when a tiger walked into the ambush and unknowingly put his paw onto the Bren gun.

Another ambush had to be aborted when an elephant began tramping around in the killing ground, threatening to crush soldiers. Depending on the content and reliability of the intelligence, an ambush could be laid for a specific short period, or continuously over many days. For 24-hour ambushes a platoon would be organised into day and night groups to allow for rest.16 Life in the jungle followed a strict routine, as Lieutenant Colin Bannister recalled:

Daily routine for a platoon patrol would follow the pattern of stand-to 30 minutes before first light when shelters were struck, equipment donned and weapons to hand. At first light, clearing patrols would sweep the perimeter, then the platoon commander and sergeant would move around the perimeter to check each man and administer paludrine (a malaria suppressant). Stand down would follow the return of the clearing patrols when weapons were cleaned and breakfast taken. Patrols for the day would be briefed and depart, leaving a small protective element in base. At all times weapons were carried and noise was kept to a minimum—communication was by field signals or whisper.

Usually by 4 pm patrols would return, be debriefed and the daily SITREP sent while the men washed, changed clothes and prepared the evening meal . . . Thirty minutes before last light would be stand-to, clearing patrols, commander and sergeant distributing the nip of rum would check the perimeter, and signal vines would be tested. At stand-down, shelters would be erected, the sentry roster started while the rest settled down to sleep.17

Those not patrolling or ambushing may have been involved in establishing radio contact with the company base, preparing for the inevitable night ambush, taking an air drop of supplies, or providing a protection party for aboriginal porters conducting a resupply of another platoon. Those more fortunate were the ready reaction forces waiting in company bases to deploy in the event of a contact. On anti-terrorist operations members of Support Company were normally required to provide foot patrols, either being allocated an area by their headquarters or, as platoons, being placed under command of a rifle company. Patrols were also conducted by administrative and headquarters personnel, and also by the attached engineer troop. Patrols were normally of two to four weeks’ duration and sometimes required carrying up to ten days’ rations.

On the third day of Operation Deuce, Support Company found an enemy camp, and on 6 January 1956, a C Company patrol was shot at, but the first deadly contact was B Company’s, on 9 January.18 A patrol of thirteen men had three armed terrorists under observation and opened fire when the group were about 60 metres away, managing to wound and capture one. The battalion’s first death occurred on 31 January when Sergeant K.H. Ewald of the mortar platoon was accidentally shot while in an ambush position. Throughout February there were a number of small inconclusive contacts, and on 14 February 9 Platoon killed a Malay civilian who wandered through their ambush site after curfew.

During February the battalion was joined by a contingent of twelve native Iban trackers of the Sarawak Rangers. These experts had been lent by the colony of Sarawak to Malaya for service against the terrorists, and served alongside all the regiment’s battalions in Malaya. The trackers were either allocated to platoon patrols or were kept centrally with the battalion tracker team to react to a contact and follow up any discovered signs.

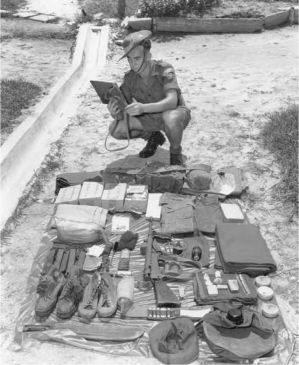

Private J. Smithergale, 9 Platoon, C Company, 2 RAR checks over his equipment as he prepares for a helicopter drop into the jungle for a fourteen-day patrol. When packed and loaded a man’s load would have been 30 kilograms for an Owen gunner and 38 kilograms for a Bren gunner (AWM photo no. HOB/659/MC).

On 4 March A Company was involved in a significant contact when a patrol from 2 Platoon struck a terrorist camp and were fired on by a number of terrorists.

In the ensuing 45-minute fight Sergeant C.C. ‘Charlie’ Anderson was mortally wounded. Quickly 11 Platoon moved to the sound of the firing and contacted six terrorists, killing one and wounding two.

Operation Deuce ended on 30 April when responsibility for the battalion’s area was handed over to the 1st Battalion of the Royal Malay Regiment, and 2 RAR was redeployed from Kedah to the state of Perak for an operation that was to continue, nearly uninterrupted, for the next thirteen months: Operation Shark North. A myriad of lessons had been learned and relearned, the most important of which were related to safety and competence in weapon handling that were stressed through the ‘Seven Simple Rules for Safety’.19 The need for good marksmanship, due to the fleeting nature of most contacts, was apparent and now all not on operations were to shoot daily as well as take part in daily weapons training.

Operation Shark North was a federal priority operation aimed at destroying communist influence in the Kuala Kangsar and Upper Perak districts, traditional strongholds of the communists. For it 2 RAR, less D Company, was redeployed to Perak with the battalion command post and Support Company being located at Kulal Kangsar, A Company at Lintang, C Company (less 7 Platoon) at Sungei Siput, 7 Platoon at Jalong Tinggi, and B Company at Kroh near the border. A Company had the first success in a contact, when on 14 May 1956 one terrorist was wounded and another killed. D Company was deployed to Minden Barracks for rest and security duties and A Company replaced it two weeks later. The operation proceeded through the rest of May and into June with a Support Company ambush, which contacted ten terrorists and killed one, being the only notable incident.

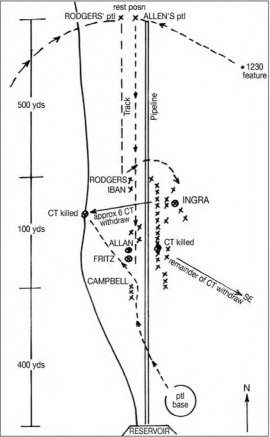

On 22 June 1956, the largest incident in 2 RAR’s tour occurred. At first light on 21 June, 1 Platoon, commanded by Lieutenant A.W. ‘Wally’ Campbell, had entered the jungle from an area of rubber in the police district of Sungei Siput. Campbell’s new platoon base, a thousand metres in from the jungle edge, was in the vicinity of a reservoir from which a pipeline ran north through the jungle to the rubber (see map 6). The next day Campbell despatched two patrols to search the jungle edge, remaining in the patrol base himself with four other soldiers. Corporal J.N. Allan commanded the first patrol of five men, and Corporal L.H. Rodgers commanded another of six men. The two patrols searched to the east and to the west of the pipeline between the reservoir and the jungle edge. At about 3.00 pm the patrols had met just inside the jungle edge where the pipe and a parallel track emerged. Allan’s patrol then moved south down the pipeline track towards the patrol base. Ten minutes later they were ambushed by a group of 23 to 25 terrorists from prepared positions on the edge of the track. The ambush was initiated by Sten and Thompson submachine gun fire and by the detonation of a mine. Most of Allan’s five men were blown over by the force of the explosion but there were no fatalities, and they scattered to fire positions. Corporal Allan was then killed by automatic fire as he tried to cross the track to get to a better fire position. Although mortally wounded, Private G.C. Fritz fired three magazines from his Owen before he died. The remainder of the patrol, although pinned down, returned fire. Private L.A. Pennant, the Bren gunner, having been blown over by the mine, was then blown off his feet a second time by a terrorist hand grenade, but kept his gun in operation and continued to rake the enemy position.

On hearing the ambush both Rodgers’s patrol and Campbell, with two soldiers from the patrol base, moved from opposite directions along the track to the sound of the firing. Rodgers’s party hit the northern flank of the ambush and he and an Iban were both wounded and pinned down. Private Arthur Falk, a member of Rodgers’s patrol, swung the remaining three men and himself around to the left, crossed the pipe and the track and assaulted the flank of the ambush. In the assault Private C.C. Ingra was killed. The assault party killed one terrorist and wounded another (who had been Ingra’s killer) as he tried to flee into the jungle. Having gained a position above the ambush site the three remaining men poured rifle, Owen and Bren fire into the enemy position.

MAP 6: 2 RAR Contact. The original sketch from the 2 RAR war diary showing the contact by Lieutenant Campbell’s platoon on 22 June 1956. A patrol led by Corporal J.N. Allan was advancing south along the pipeline when it was ambushed by a group of terrorists and two Australians were killed. A patrol led by Corporal L.H. Rodgers came to their assistance from the north while Campbell and two men advanced from the south. A further Australian was killed. The bodies of two dead terrorists were recovered and the remainder escaped.

As Campbell and his two men ran down the track from the other direction they were fired on from the ambush position, and returned fire. Campbell then threw two grenades into the area from where the fire came and those enemy withdrew.

The remainder of the enemy, reacting to a series of whistle blasts, also withdrew from the ambush. Campbell and his two men then swept into the ambush position where they located and killed one CT and recovered a Thompson submachine gun.

The number of CT casualties could not be determined.20 The remainder of Operation Shark North was less dramatic. In August there were two contacts, one saw Private A.W. Sands shot in the shoulder and he had to be carried for eight and a half hours before he could be evacuated, and the second was by a D Company patrol. Neither contact resulted in known terrorist casualties.

From 19 September the emphasis on Operation Shark North was changed from ‘scrub bashing’ to concentrate on the villages and the labour lines on the rubber estates in the Sungei Siput area, using static checkpoints on village gates, snap checks on roads and night patrols and night ambushes to deny food and supplies to the terrorists. On 21 October a Headquarters Company ambush party attached to A Company ambushed four terrorists and killed one in an incident reported in the commander’s diary as reflecting ‘the greatest credit on their courage and fire discipline which were exemplary’. In November B Company wounded one terrorist and in two separate incidents, C Company wounded two terrorists and killed one.

By December 1956, 2 RAR had been in the field all year and it was decided to withdraw the battalion to Minden Barracks for retraining until February 1957. The aim of the retraining, according to the training instruction, was to ‘ensure that all ranks return to operations rested, refreshed and fit with a view to eliminating as quickly as possible the CTs in the area of operations’. This was to be achieved by antiterrorist training concentrating on weapon handling and ambushing, on a complete overhaul of all aspects of unit administration, and organised sport and recreation.

February 1957 found the battalion deploying once again on Operation Shark North. Headquarters 2 RAR, Headquarters Company and B Company were located at Kuala Kangsar, tactical headquarters and A Company went to Sungei Siput, D Company went to Lasah, and Support Company to Sungei Kuang. The battalion began the now familiar procedure of settling into an area, embarking on familiarisation patrols and carrying out aerial reconnaissance. In mid-February a police patrol working with the battalion killed one terrorist, and on the 20 February B Company had a bloodless chance contact with a terrorist.

Helicopters were an important factor in enabling the rapid deployment of troops. In February 1957, a large number of communist terrorists were reported in the Sungei Siput area and about 70 men of A Company, 2 RAR were deployed by air in an endeavour to locate them. With their equipment, the soldiers board one of the two RAF helicopters which were running a shuttle service into a remote jungle landing zone. A Company was not successful in locating the enemy, but B Company had a contact (AWM photo no. MEL/215/MC).

Shark North was interrupted in mid-February when, based on exceptionally accurate information from the Special Branch, the commander 28th Brigade suddenly and secretly concentrated nine companies from his three battalions plus supporting troops into a narrow jungle salient in the Kuala Kangsar–Kinta districts.

2 RAR provided a tactical headquarters, Support Company, B and D Companies, with the remainder of the battalion remaining on Operation Shark North.

Operation Rubberlegs was aimed at disrupting and inflicting casualties on the 9th MCP District organisation, and to do this, all elements had to deploy secretly into the area, which involved 2 RAR carrying out a night crossing of the Sungei Perak in assault boats. Of note was the technique used to assist jungle navigation at night by the use of vertical searchlight beams as the basis for resections. As well, patrols operated much closer than was normal using strict rules of engagement and wearing distinguishing yellow headbands when there was a likelihood of a patrol clash. The overall operation resulted in the death of two terrorists and the wounding of two others. 2 RAR’s contribution was the discovery of a well-equipped armourer’s workshop. The operation ended on 7 March for most, though five 2 RAR ambush parties remained behind in the jungle for another ten days.

Throughout March and April 2 RAR returned to anti-terrorist activities as part of the continuing Operation Shark North. In late May elements of 2 RAR were again diverted from Shark North to follow up information given by a surrendered terrorist about the location of a camp for 72 terrorists located on the Thai border. Operation Eagle Swoop, as it was called, planned that an eighteen-man patrol, commanded by Lieutenant Campbell, would act on the surrendered terrorist’s information and move with him to the border area, while another patrol of thirteen men, under Lieutenant James Burrows, acted as support and as a radio relay when Campbell discovered the camp. Campbell’s patrol was assisted on the first day so that the hard climb to the ridgeline that marked the border was achieved quickly. Thereafter progress was slower, as much from the need for stealth and silence as from their heavy load of fourteen days’ rations, water, ammunition and equipment. Unfortunately, the terrorist’s information was stale and no contacts were made.

After about three weeks Campbell’s patrol returned to Kroh and a Support Company patrol under Lieutenant Alex Orr was despatched to search an area where Campbell had seen fresh footprints. On 24 June 1957, four men from Orr’s patrol came across a camp occupied by 30 terrorists and in the initial exchange of fire Privates T.B. Hellard and J.F. Potts were killed, and two others were wounded. Corporal Des Kennedy showed great personal courage and leadership in the contact and was subsequently awarded the Military Medal. Other patrols were inserted into the area in an attempt to cut off the terrorists before they could make good their escape, but to no avail.

On 1 August, 2 RAR was withdrawn from operations in Perak and concentrated on training for ‘major warfare’ prior to its embarkation for Australia in October. The aim of the training, according to the Training Directive, was to prepare for ‘. . . major warfare against a first class Asian power with a predominance in manpower and with an atomic potential up to 2 kilotons’. The specialist platoons of the battalion were deployed to the FARELF Training Centre for various periods over the next few months, the rifle companies trained from their company bases and a battalion exercise was conducted.

The departure of 2 RAR corresponded almost exactly with a milestone in the Federation of Malaya’s political history when on 31 August 1957 the country celebrated its independence. The 2 RAR band played at the celebrations in Penang and the battalion provided a guard at the retreat ceremony marking the last lowering of the British flag in the colony. During two years in Malaya, the battalion had lost seven soldiers killed in action, and a plaque to their memory was erected in the chapel at Minden Barracks.21 On 15 October 1957, two years to the day since the MV Georgic had anchored in Penang Harbour, the battalion embarked in the MV New Australia for the return journey to Australia. The battalion arrived in Sydney on 31 October 1957 and was given a ticker-tape welcome as 100,000 people lined the streets when it marched through the city. Meanwhile, their replacement, 3 RAR, was already training in southern Malaya.

Denial Operations—3 RAR in Malaya

On 2 September 1957, the advance party of 48 3 RAR soldiers had left Sydney Airport for the FARELF Training Centre in Malaya, and on 13 September the party was followed by the battalion recce party, comprising the 38-year-old commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel J.F. White, and the intelligence officer, Captain James Hughes, with their families. John White had graduated from Duntroon in June 1941 and had served in the AIF, including a period with the 1st Australian Parachute Battalion. He had been a company commander with 3 RAR in Korea and the brigade major of the 28th Commonwealth Brigade. The RSM was initially WO1 L.C. ‘Darkie’ Griffiths, with WO1 Joe O’Sullivan taking over from him during the tour. The battalion’s second-in-command, Major Max Simkin, had already been in Malaya for several months on operations with 2 RAR.22 On 20 September the administration advance party left Australia for Nee Soon Camp in Singapore to organise the arrival of the main body of the battalion that left Sydney on 25 September 1957.

Despite a collision between the battalion’s troopship, MV New Australia, and a tanker near Thursday Island, and a subsequent period of repairs, on 11 October the troops and their families disembarked at Singapore with the troops being trucked immediately for training at the FARELF Training Centre at Kota Tinggi in Johore.

The accompanying families went on by air and rail to Penang.

On 22 November the battalion departed the training centre in Johore by train for the north of the peninsula. A and B Companies and the battalion command post detrained at Sungei Siput where B Company, the assault pioneer platoon and the command post stayed, while A Company moved by road to Lasah. The remainder of Battalion Headquarters, Administration Company, and C and D Companies continued on to Kuala Kangsar, while the remainder of Support Company detrained at Prai, and took the ferry to Minden Barracks. On 1 December, 3 RAR became operational and began routine anti-terrorist activities as part of the ongoing Operation Shark North. The only contacts during this period were made by 2 Platoon. The first occurred on 7 January when a group of terrorists approached a section position and were challenged by a sentry. The terrorists opened fire and then appeared to form an assault line. The section returned the fire but before the communists broke contact, Corporal M.A. Smith was wounded. Two days later, a similar incident occurred when, late one evening, a section’s sentry fired at a group of terrorists walking down the track towards him. They escaped but it was later confirmed that two were wounded.

Soon after arriving in Malaya in October 1957, 3 RAR underwent training at the Far East Land Forces Training Centre at Kota Tinggi, in eastern Johore. This photograph shows members of the assault pioneer platoon moving out of the jungle into a stream on their way to a ‘jungle lane’ for firing practice under realistic conditions (AWM photo no. 1957/ELL/18/MC).

In mid-January 1958, the emphasis of operations in North Perak changed to that of food denial carried out by the whole of the brigade over its entire area, and all of 3 RAR was involved except some Support Company and Administrative Company elements at Penang. Operation Ginger, as it was known, involved all of 28th Brigade, 2nd Federal Brigade who also operated in Perak, police, Royal Artillery and Royal Australian Artillery units and the troop of Royal Australian Engineers.23 The area of operations covered 3100 square kilometres and, it was estimated, contained approximately 195 CTs and hostile aborigines. The goal was to deny food to the terrorists while ground patrols searched between their bases and their supply sources.

On 16 February Corporal Wally Brown and ten soldiers ambushed a party of at least two communists. In the brief exchange of fire Private F.S. Warland was wounded in the leg but no known casualties were inflicted on the enemy. On 10 March Sergeant Ron Jepperson and ten soldiers from the Machine Gun Platoon in an ambush heard four to six terrorists 50 metres away. The ambush was sprung but no results were achieved.

On the day before Kapyong Day 1958, 3 RAR killed its first terrorists. A jeep patrol of C Company soldiers led by Corporal Wally Brown temporarily under command of B Company contacted three communists and in a running engagement through the rubber killed one Chinese and one Indian terrorist.24 Kapyong Day, the only day during the two-year tour when the battalion was together, was celebrated in an appropriate way. In May the mortar and machine-gun platoons took part, at different times, in exercises with other brigade units in the Kinta Valley to test skills for the battalion’s major war role.

On 3 July 6 Platoon, commanded by Lieutenant Claude Ducker was using three-man patrols. One of these was fired upon from a camp occupied by four terrorists. One of the scattering enemy then headed towards Sergeant Moyle’s patrol and was shot by Private O’Brien. On 27 July a three-man ambush patrol from the assault pioneer platoon, consisting of Lance Corporal M.P. ‘Max’ Hanley, Private Ramsey and Private Mullings, and operating with B Company, killed three terrorists and wounded one. This ambush was set as the result of the company commander, Major Ron Garland, noticing a large drum of sweet potatoes left in the corner of a mangling shed in the rubber. Garland located the ambush position in the shed and at about 9.00 pm the party was alerted by the imitation of a dog barking. Half an hour later, four terrorists appeared out of the darkness. As the terrorists entered the shed to collect the sweet potatoes, Hanley sprung the ambush at three metres range by shooting the first man. The second and third terrorists were also killed by the first burst at the edge of the shed. Hanley then shot a fourth terrorist as he disappeared into the jungle, wounding him.25

The next day the wounded CT and his wife surrendered to a 3 RAR road patrol mounted in a Ferret scout car driven by Private ‘Ossie’ Osborne, with one of the batmen in the turret manning the .30 calibre machine-gun. Coming unexpectedly upon the wounded terrorist and his wife, Osborne halted the Ferret close to the pair and leapt out, yelling to the batman in the turret to cover them with the machine-gun. As the batman did this he quietly informed Osborne that the gun was not loaded and, anyhow, he did not know how to operate it. Osborne pulled out his own pistol, covered the two terrorists as he disarmed them, then surreptitiously loaded his own weapon, a step he had omitted to take in his haste to leave the company base.26 The terrorist was Lam Poh, a hard-core branch committee member who was subsequently induced to give information. He agreed to lead security forces to his comdrades’ camps, and during July and August he led directly to the elimination of his Jalong Armed Work Force, and 31 Independent Platoon, either through capture or surrender, with the remnants being forced to cross the Thai border. However, the success of this operation was not revealed in the Malay papers until late September, once the full intelligence value had been obtained from Lam Poh.

In August and September 1958, there were three inconclusive contacts by 1, 3 and 6 Platoons but soon the tracker team had a success. Such a team had not been used by 2 RAR but in April 1958 it was decided to integrate the dogs, their handlers and the Iban trackers into a single unit. Most of the team, which consisted of ten Australians, four Ibans and four dogs, had received individual training for their tasks at the FARELF Training Centre. It was initially raised by Lieutenant Peter Phillips, who was replaced by Lieutenant Ducker in August. Normally held centrally at Lasah Camp on five minutes’ notice to move, and then deployed when a track was found, the team, in October, followed enemy tracks for nine days over 30 kilometres of jungle until the tracks were wiped out by monsoonal rain.

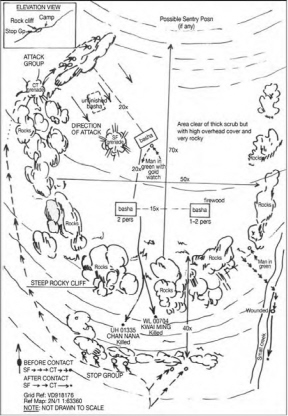

On 20 November 1958, a patrol from 3 Platoon found signs of an enemy group and an eleven-man tracker team, led by Lieutenant Ducker, was deployed.

A few hours later, while moving up a rocky ridgeline, the patrol saw two sheets of new green plastic obviously being used as shelters, about 40 metres ahead (see map 7). Ducker left six of his men under command of Corporal Noel Peck at the lower edge of the camp as a stop group, and took the other four round by the left flank to the rear of the CT camp. During the eight minutes that it took Ducker’s group to move to the flank, the stop group were able to locate and cover individual terrorists within the camp. Ducker’s intention was to assault from the high ground and drive the enemy onto the stop group. The assault was initiated by Ducker throwing a grenade at a terrorist group which had been seen, and then his group moved, firing, into the camp. Almost simultaneously the communists reacted by also throwing a grenade and for some seconds returned the Australians’ fire before they fled downhill. As soon as the grenades exploded Private Colin Kinch shot one communist. Directly after this the stop group killed another two flushed out by Ducker’s group. The significance of the kills became apparent when it was discovered that the terrorist killed by Kinch was a district committee member who had been involved in the 1951 assassination of Sir Henry Gurney, the British High Commissioner.

MAP 7: 3 RAR Contact. The original sketch from the 3 RAR war diary showing the contact by the Tracker Platoon on 20 November 1958. The platoon commander, Lieutenant Ducker, left a stop group at the southern edge of the communist terrorist camp, took four men to the left, around the camp, and advanced south through the camp.

In the first months of 1959, when the battalion began rotating one company at a time through a two-month ‘major war training’ program, the counterinsurgency operations continued. On 21 April 1959, Operation Ginger, the food denial operation which had provided the framework for most of 3 RAR’s activities since January 1958, ended. The total eliminations from all units involved was 150, of which the 3 RAR share was nine kills, two captures and two surrenders. The overall result of these efforts was the declaration of Perak as ‘white’—a secure area.

In early May in the Grik district near the Thai border, the assault pioneer platoon and 8 Platoon were operating with two platoons of 1st Battalion, New Zealand Regiment (1 NZR). On 5 May two terrorists approached an ambush set up by the pioneers. Springing the ambush killed one terrorist but the other escaped.

In late July and early August, C Company with 6 Platoon, two A Company platoons and the tracker team under command, participated with other 28th Brigade units in Operation Hammer, an attempt to locate two enemy camps located in the midst of hostile aboriginal settlements. Following a 40-kilometre walk through mountainous jungle in three days, security was lost when a Sakai tribesman, apprehended by the tracker team, escaped from the base camp. Also, while troops were crossing a tributary of the Sungei Perak, a group of about twenty tribesmen on a raft came around a bend in the river. 6 Platoon, commanded by Lieutenant Des Mealey, apprehended the entire group but the noise of the tribesmen accompanying the platoon did not help the chances of surprising a communist camp, especially after one of the women noisily gave birth at Mealey’s headquarters.

On 12 September 1959, 3 RAR was withdrawn from operations in preparations for its departure, content in the knowledge that it had killed ten CTs for the loss of two soldiers wounded in action. Four soldiers had died, none as the result of enemy action.27 Earlier that year, Major John Milner, the second-in-command of 1 RAR, destined to replace 3 RAR, had been posted to 3 RAR as officer commanding A Company, to gain experience. On 23 September the commanding officer of 1 RAR, Lieutenant Colonel W.J. Morrow, visited 3 RAR. On 2 October the MV Flaminia arrived and disembarked 1 RAR in Singapore. Two days later the vessel arrived in Penang and by 6.00 pm and next day, having embarked A Field Battery, 2 Troop RAE, 3 RAR and families sailed for Australia.

Maintaining Pressure—1 RAR in Malaya

The last battalion of the Royal Australian Regiment to serve in Malaya during the Emergency was 1 RAR, commanded by the 38-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Bill Morrow, who had graduated from Duntroon in 1941, served as a platoon commander in New Guinea and Borneo in the Second World War, as a 3 RAR company commander and a brigade major in Korea, and was among the first five officers to march into the battalion the day it was formed in Balikpapan. The RSM was WO1 F.G. Buchanan, who had been in the regular army since 1938 and had served in the Middle East, Darwin and Balikpapan.

The battalion had served in Korea twice and had only returned to Australia in April 1956. Based at Enoggera, 1 RAR was, as one journalist put it, ‘practically regarded by Queenslanders as their private property’.28 Leaving Septimus, its Shetland pony mascot, at Gatton Agricultural College but taking the colours, 1 RAR embarked in the MV Flaminia on 20 September 1959. Following an uneventful trip broken only by physical training and lectures, the 468 soldiers (of whom 219 were Queenslanders) and four wives, disembarked in Singapore on 2 October. Ultimately some 200 families moved to Malaya.

After disembarkation, the battalion went to Nee Soon Camp on Singapore Island, where the battalion spent ten days acclimatising and being kitted out.

In-country training for 1RAR was carried out in Kota Tinggi at Nyassa Camp, using the resources of the Jungle Training School. On 9 November the battalion was ready for operations and deployed to Perak State. Battalion Headquarters, Support Company and Administration Company were based at Kuala Kangsar, A Company went to Lasah, B Company went to Sungei Siput and C Company went to Lintang. These bases were only a brief stop along the way to where 1RAR was to spend most of its tour, and soon the soldiers found themselves being driven, flown, being carried by boat or walking to the Thai–Malayan border area. By 23 November 1 RAR had taken over all positions of the 1st Battalion, the Loyal Regiment on the border and operations began. As well, the battalion inherited a tiger cub as a mascot.

1 RAR’s first operation was Operation Bamboo, a deep jungle operation in Upper Perak in country abutting the Betong salient, for which an advanced battalion headquarters was set up at Grik. The existence of large numbers of terrorists in the Betong salient was well known and camps had been located by visual reconnaissance within 300 metres on the Thai side of the border. In these initial stages the communists enjoyed a form of sanctuary in Thailand as the security forces were not permitted to cross the border.

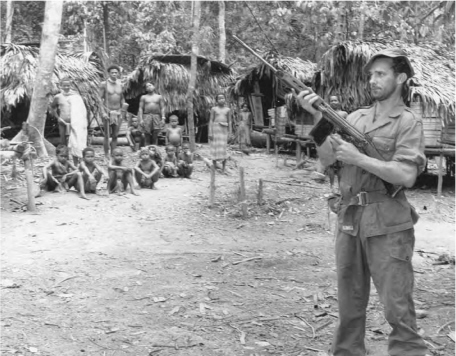

As they lived deep in the jungle and were an obvious source of food and intelligence for the communists, the support of the Malayan aborigines was crucial. Private J. McLear of A Company, 1 RAR stands guard in an aboriginal village in northern Malaya. In return for information about the terrorists’ movements the troops kept a protective watch on villages to prevent possible retaliation (AWM photo no. CUN/401/MC).

The border is an area of extremes with rainforest-clad mountains reaching as high as 1500 metres. Roads were virtually non-existent although there were numerous animal tracks on ridgelines used by both the communists and the security forces. In places the valleys were so steep that it was too hazardous for the supply-dropping Valettas to manoeuvre, and sub-units had to choose alternative dropping zones.

Generally the rivers and creeks ran from north to south and for most of the year were almost impassable torrents, but in the dry season they were often reduced to a trickle. The population consisted of a few aborigines, some of whom supported the communists with food and intelligence.29 The aim of the operation was to eliminate the courier system that the communists were using between their remnants in Malaya and the party hierarchy in Thailand.

1 RAR was deployed immediately south of the border and the two other battalions in the brigade, 1 NZR and 2/6th Gurkha Rifles, attempted to squeeze the communists from the south. As soon as the operation started the majority of the communists fled to Thailand leaving only a token presence, and of course the couriers. The difficulty of the task was that the brigade was trying to intercept courier traffic that amounted to no more than a few people a month. Although the terrorists were not aggressive there was always the chance that a terrorist unit would ambush an unwary security force element. In November a patrol from 4 Royal Malay Regiment, working on an adjoining stretch of border, had contacted a group of between fifteen and twenty terrorists with blue hatbands (which was the recognition symbol of 1 NZR) and called on the Malay patrol, in English, to surrender. The terrorists then opened fire on the patrol but fled back across the border when the Malay patrol charged them.

Between November 1959 and the official end of the Emergency on 31 July 1960, 1 RAR carried out exhaustive patrols along the border. As one area was searched the battalion would be redeployed to another area. Signs of the enemy were frequently found, some only hours old and some many months. The battalion tracker team was frequently deployed and spent days following trails that were ultimately lost in rough country or were washed out by heavy rain. Contact with the enemy eluded the battalion. Even when the mortar platoon saw two figures crossing some rapids at night using a torch, and fired on them, it eventuated that they were aborigines.

The frustration of working on the border was heightened by the fact that patrols frequently could see campfires, hear shots being fired, wood being cut, voices and even, on one occasion, a dam being built just across the border. In February, 7 Platoon found a complete CT armourer’s workshop that they then ambushed unsuccessfully for some time. In March, a section of the assault pioneer platoon was forced to abandon its ambush site because of heavy tree falls in a particularly fierce storm.30

A variation to the daily routine of border patrols occurred in April with Operation Magnet. This operation was noteworthy as it was the first where a Malay unit was to cross into Thailand and attempt to drive the communists south to where 28th Brigade units were waiting. However, 1 RAR again had no contact with the enemy. In June a similar operation was tried, this time with a platoon from 1 RAR on the Malayan side of the border and a police field force unit moving parallel on the Thai side. This was known as Operation Jackforce. On 6 July, 4 Platoon fired on a man wearing green shorts and a green jacket, with no result. On 28 June Lieutenant Colonel Stuart Weir assumed command of 1 RAR, when Lieutenant Colonel Morrow returned to Australia to command 3 RAR during its pentropic reorganisation.

On 31 July 1960, the Prime Minister of Malaya, Tunku Abdul Rahman, signed a proclamation ending the Emergency. Next day there was a great victory parade in Kuala Lumpur where the King of Malaya took the salute as 6000 Malayan and Commonwealth Troops, 400 vehicles and 70 aircraft passed in review. Although the majority of 1 RAR remained on operations the colours were on parade carried by Lieutenants Peter White and Ian Teague. For Malaya, the Emergency had ended, but for 1 RAR, patrols on the border were to continue, without enemy contact, for another twelve months.

The battalions of the Royal Australian Regiment came late to the Malayan Emergency, a war that had been running for seven years and four months before Australian infantry involvement. When 2 RAR arrived in Malaya in October 1955, it joined an infantry force that had risen from ten battalions in 1948 to a peak of 23, two-thirds of the communist terrorists had been eliminated, and most of the peninsula had been declared free from communist influence. Only two months before 3 RAR arrived, in July 1957, a significant milestone was achieved in Malayan security when for the first time since the Emergency began a month passed without a single soldier, policeman or civilian being killed by terrorists. As 1 RAR began operations the military situation was described by one historian as having ‘been reduced to the level of a mopping-up operation’. In all of 1960 there were no military, police or civilian casualties.31 Still, it must be remembered that it had been a long, vicious little war. When the Emergency ended 6398 terrorists had been killed and 2760 wounded. The security forces suffered 1851 killed and 2526 wounded. Civilian casualties were 2461 killed, 1383 wounded and 807 missing.32 During the Emergency, Australian infantrymen of three battalions over a period of almost five years were involved in 45 contacts and killed seventeen communist terrorists. Seven members of the regiment were killed in action.33 Killing, wounding or capturing terrorists was only part of the picture, however. The truth was that the contribution of the battalions of the regiment that served in Malaya during the Emergency cannot be summarised accurately in such terms. The Lam Poh incident, where the initial contact resulted in just a small number of dead and wounded, but which subsequently led to a most significant number of successes over a wide area, was a good example of the types of accomplishments that counted. Furthermore, no battalion could view its results in isolation. They were always part of a larger operation in which the final result was not necessarily obvious to the individual soldier in the jungle. In these operations the Australian battalions played their allotted roles effectively as part of the 28th Brigade.

Success in such an environment demanded a high degree of discipline and professionalism by all ranks. Many of the officers and soldiers had previously served in Korea, and their expertise was valuable. But the Emergency also provided the young officers and soldiers, who had not served in Korea, with operational experience that was to stand them and Australia in good stead in later years. Just to locate the terrorists in vast tracts of jungle and mountains required a high standard of bushcraft and perseverance. To conduct an ambush successfully against an elusive foe, who had already survived years of similar attempts, required patience, discipline and often plain luck. It was a patrol commander’s war demanding highly competent junior NCOs. The members of the regiment were learning what it meant to be a regular soldier when their country was nominally at peace, and they could feel proud of their achievement.

For the Royal Australian Regiment, the Malayan Emergency required the painstaking application of careful training. There were two major results from this grinding attention to the detail of infantry soldiering over five years in Malaya. The first was the continuing existence of Malaysia as a stable and democratic country.

The second was the opportunity experienced by infantrymen of the regiment to absorb, and then develop, the jungle warfare skills evolved by the British Army in its most successful counterinsurgency war. The contribution of the Malayan Emergency to the development of professionalism in the Royal Australian Regiment cannot be overstressed. Many of the platoon commanders and soldiers in Malaya served in infantry battalions ten years later in Vietnam and the grounding in Malaya proved invaluable.