6 Consolidation and Reorganisation Australia, 1950–65

John Blaxland

The winding down of the BCOF during the late 1940s meant that the regiment had to find a home back in Australia. During this time 1 RAR was located at Ingleburn, NSW and 2 RAR at Puckapunyal, Victoria. The outbreak of the Korean War, however, upset hopes that there might be some stability in the regiment, and soon these two Australia-based battalions were busy training reinforcements for 3 RAR on operations in Korea, before they too found themselves preparing for overseas service.

By September 1951, when 1 RAR was warned for operations in Korea, over 1000 men had passed through the battalion for service in 3 RAR. With the commitment of 1 RAR, 2 RAR took up the full training responsibility, conducting both recruit and infantry corps training for the reinforcements for the two battalions in Korea. By the time 2 RAR set sail for Korea on 5 March 1953, some 300 officers and 4500 other ranks had passed through the battalion. One soldier, Private G. R. Belleville, stowed away on board before the ship sailed because he had been posted out of the unit a few days before. He was fined £5 and was taken back on strength. He subsequently attended the Officer Cadet School at Portsea, became an officer in the SAS Company (RAR), and was killed on active service with the Australian Army Training Team, Vietnam in February 1966.

The decision to increase the Korean commitment to two battalions posed considerable problems as it was generally accepted that one battalion was required in Australia to maintain another overseas. To ease this problem it was decided to form a Royal Australian Regiment Depot from the rump of 1 RAR remaining at Ingleburn. The RAR Depot was formed on 18 January 1952, and in July 1952 the role of infantry corps training passed from 2 RAR to the RAR Depot, which although it had a permanent strength of only about 40 personnel, trained large numbers of reinforcements for Korea. Lieutenant Colonel John McCaffrey assumed command of the depot on 18 February 1952. Two months later the RAR Depot was redesignated 4 RAR to carry out ‘depot’ duties and McCaffrey was appointed commanding officer with effect from 7 May 1952.1

It was clear that once the Korean War ended, accommodation would have to be found for the returning battalions, and construction of the new barracks began at Enoggera, in Brisbane. By the time 1 RAR returned from Korea in April 1953 the new barracks were ready. After leave and reposting the battalion recommenced training, but by September elements of the battalion were at Bowen in north Queensland, where the local waterside workers (and soon the train drivers and meat workers also) were on strike. There the members of the battalion found themselves stevedoring and train driving. In 1954 the battalion began preparation for its return to Korea and also for the visit to Australia of Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II, for which it lined the Brisbane streets. On 20 March 1954, 1 RAR marched through Brisbane, embarked that night in MV New Australia, and arrived at Pusan on 31 March.

On 6 April 1954, 2 RAR embarked in Korea and arrived back in Brisbane on 16 April to take over the Enoggera lines recently vacated by 1 RAR. Like 1 RAR, 2 RAR went through the same cycle of leave, postings and training in preparation for its next overseas tour. The Jungle Training Centre (JTC) had recently been re-established at Canungra, south of Brisbane, and 2 RAR was the first unit to pass through the centre, beginning with A Company in January 1955. Colours were presented to 2 RAR on a parade at Victoria Park, Brisbane, on 28 September 1955 by the Governor-General, Field Marshal Sir William Slim, and thus 2 RAR became the first regular army unit in Australia to receive its colours. After the parade the battalion marched through the city of Brisbane, its last public appearance before once again proceeding overseas, destined for Malaya.

Following its first tour in Korea, 1 RAR had spent only eleven months in Australia before returning for garrison duties along the armistice line. 2 RAR had spent a little longer in Australia—seventeen months—before it too returned to overseas service.

Although some members of these battalions had found time to be married during their short stay in Brisbane, neither battalion had time to establish links with the community. And 3 RAR, which arrived back in Australia six months after 2 RAR, had not served in Australia since it was formed as 67th Battalion in 1945.

The Korean War armistice was signed in July 1953 and after a period of garrison duty in Korea 3 RAR arrived in Brisbane on 20 October 1954, paraded through the city and was welcomed by the Governor-General, Sir William Slim. The unit then re-embarked and proceeded to Sydney where it marched through the city on 22 October. From February 1955 4 RAR and 3 RAR were at Ingleburn, and at the end of 1955 4 RAR was absorbed into 3 RAR. On Kapyong Day 1956, Sir William Slim presented the Queen’s and regimental colours to the battalion, and in June 1957, the battalion moved to Holsworthy, NSW, taking over the former national service barracks. There were only a few months before the battalion was to move to Malaya so training was stepped up until the unit set sail on 24 September 1957.

With the departure of 3 RAR, the RAR Depot, still officially called 4 RAR, was re-formed as an infantry training centre, and when the School of Infantry moved from Seymour to Ingleburn in 1960 it absorbed the RAR Depot and took over its role of corps training. During its short existence 4 RAR had never been a proper infantry battalion, but for many young soldiers it provided a lasting introduction to life in the regiment.

The formation of the RAR Depot and its title of 4 RAR emphasised the fact that it was not envisaged that the regiment would always remain at only three battalions, and by the mid-1950s another RAR element had been in existence for several years. Towards the end of the Second World War the army had raised a parachute battalion, and there were a number of advocates for raising a similar capability in the postwar period. Eventually it was decided to raise an airborne platoon in the Royal Australian Regiment. Formed on 23 October 1951 at the School of Land–Air Warfare at Williamtown, NSW, the platoon initially comprised one officer and nine soldiers, drawn from 2 RAR. On 1 January 1953, the platoon became a separate unit and severed its link with 2 RAR. By this time it had expanded to a normal platoon size of approximately 33 soldiers. The platoon had the roles of land–air warfare tactical research and development, demonstrations to assist land–air warfare training and AMF recruiting, airborne firefighting, airborne search and rescue, and aid to the civil power. An effort was made to ensure that volunteers had seen active service, preferably in Korea, but there does not appear to have been an operational role for the platoon.2

Captain C.P. Yacopetti, MC, instructing Lance Corporal J. Lynan of the 42nd Infantry Battalion in April 1958 during an assault pioneer course at Enoggera, conducted by the School of Infantry. Captain Yacopetti was awarded the MC and was mentioned in despatches as a result of actions in Korea with 3 RAR (AWM photo no. CUN/180/NC).

In April 1956 1 RAR, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel O.D. Jackson, returned to Brisbane from Korea. A long period of retraining and resettlement followed. In November and December of that year the battalion went on a series of marches aimed at raising the profile of the army in such places as the Darling Downs, the Brisbane Valley and the north coast area of New South Wales. On 30 March 1957, now under Lieutenant Colonel W.J. Finlayson, the battalion received its colours from Sir William Slim, at a parade on the Brisbane Exhibition Ground. Throughout the next three years 1 RAR was occupied with training as part of the 1st Independent Infantry Brigade. The battalion was also responsible for training the reinforcements for 3 RAR, then serving in Malaya, and a large part of this training was conducted at JTC, with the assistance of the centre’s staff.

On 31 October 1957, 2 RAR returned to Australia from Malaya, moved into the barracks at Holsworthy and, with Lieutenant Colonel W.G. Henderson as commanding officer, became part of the new 1st Independent Infantry Brigade Group. Alongside 1 RAR, 2 RAR took part in the two brigade exercises in 1958 and 1959. During this period the regimental colours were trooped at the Sydney Showground on 11 October 1958 and the Queen’s colour was trooped before Princess Alexandra at the Sydney Showground on 11 September 1959. The battalion thereby became the first regular Australian unit to troop the colours before royalty and the first unit to perform this ceremony with the new FN 7.62 mm SLR.

Though the regiment maintained one battalion in Malaya from October 1955, the conclusion of the Korean War meant that for the first time a degree of stability and predictability was developing within the life of the battalions. For the first time attention could be given to the development of the regiment within the army and in accordance with defence thinking. The result of this attention was to be three significant army reorganisations over the next ten years that would have far-reaching implications for the shape of the regiment.

As described in the previous chapter, the end of the war in Korea, the French defeat in Indo-China and the formation of the South-East Asia Treaty Organisation caused a reappraisal in strategic thinking, putting greater emphasis on possible military activity in the South-East Asian region.3 But if the army was to have forces available for such deployments at short notice, the structure of the army’s operational forces had to be reviewed. The conclusion reached in 1956 was that the minimum requirement would be a ‘mobile, hard-hitting’ regular brigade group in addition to the battalion group with the strategic reserve in Malaya. To free personnel for the regular brigade group some of the regular army manpower, then devoted to the Citizen Military Forces and national service, would have to be reassigned, and amendments would need to be made both to the CMF and the national service scheme. On 31 October 1956, the Military Board presented this plan to the Minister for the Army, Mr J.O. Cramer. It was proposed that a new headquarters for the brigade be raised and that the brigade group would consist of two infantry battalions, one armoured regiment, one field artillery regiment, one field engineer squadron, one special air service squadron, and elements of signals, supply, transport, medical, ordnance and workshop units. The complete strength was to be 252 officers and 4331 other ranks.

Consequently, in September 1957 Cramer announced a new mobile regular brigade group organisation, ‘designed to produce the best balance [of capabilities] for possible operations in the varied terrain of the South-East Asian area’. In this respect its role differed from that of the previous conventional brigade type, which was not designed for independent operations. The regular army field force had, in theory, consisted of a ‘brigade group’ of sorts since 1947, which in effect was a standard brigade with certain attachments, but plans to build on this never came to fruition due to operational commitments.4 This new brigade group, the 1st Infantry Brigade Group, was to be mobile, hard-hitting and air portable to the greatest possible degree. The concept was in line with the general trend being followed in the United States and Britain, where emphasis was being placed on both mobility and firepower. The new regular army brigade commander (Brigadier J.S. Andersen, from its inception in 1957 to late 1959, and Brigadier W. Wearne from late 1959 to 1960) would now have a substantial number of units under his command, including an infantry brigade headquarters, two infantry battalions (1 RAR and 2 RAR), 1 Armoured Regiment, one field engineer squadron, the Special Air Service (SAS) Company, one independent field squadron and various service and support units. These units were mostly based in Eastern Command but were spread out between Swanbourne (Perth) and Enoggera (Brisbane). 1 RAR was based at Enoggera and 2 RAR at Holsworthy.5 To enable the formation of this group, the National Service Training Scheme was scaled down to release 2000 regular soldiers. The money saved from these cutbacks could be used, it was argued, to buy modern equipment. For the first time, the battalions were allocated specific roles within the framework of the field force. Furthermore, the battalions were given the necessary equipment and freedom from other commitments (support of the CMF) to train effectively. The new brigade group was headquartered at Gallipoli lines, Holsworthy, in barracks formerly occupied by a national service battalion and later to be shared with 2 RAR upon their return from Malaya.6 The first brigade exercise was held in February 1958 at Holsworthy and at Kangaroo Valley, south of Sydney. The 1959 brigade exercise—Exercise Grand Slam in the Mackay area of Queensland—was the first major brigade exercise conducted in Australia since the Second World War, and was extremely valuable, particularly for 1 RAR, which had again been warned for active service in Malaya.

The battalions serving in Australia during the period from 1957 to 1965 acted as the home base for battalions on overseas service in Malaya, but with the end of the Malayan Emergency in 1960, the regiment faced no formal operational commitment (except for the occasional operations interspersed between training for the battalion on rotation in Malaya) until the period of Confrontation with Indonesia in 1965. It was therefore an appropriate time for the army to consider implementing a further reorganisation of the field force.

Introduction of the Pentropic Organisation

On 26 November 1959, the Minister for Defence, Athol Townley, announced a new three-year defence plan, including the abolition of the National Service Training Scheme, a 50 per cent increase in the volunteer strength of the CMF, and a 35 per cent increase in the strength of the regular army brigade group. He also foreshadowed the introduction of the pentropic reorganisation, which army planners were in the process of finalising and preparing for promulgation. The Chiefs of Staff, in June 1959, argued that ‘the primary emphasis must henceforth be placed on the Regular Army itself, its secondary task being to train and administer a CMF to support it if necessary’. This was the reverse of what had been the case until 1959 and was to signify a major advance in terms of the priority of planning which was to be placed on the regiment.7

Following this announcement, the organisational emphasis was temporarily placed on increasing the strength of the two-battalion brigade group by adding an extra battalion, as the final plans for the introduction of the pentropic organisation, foreshadowed by Mr Townley in his speech in November 1959, were still being prepared. It was decided that the brigade would be increased from 4000 to 5500 men, with a logistic support force of 3000.8 This was to be in addition to the battalion group maintained in Malaya as part of the British Commonwealth Far Eastern Strategic Reserve. These plans, however, were overtaken in 1960 by the implementation of the pentropic division.

In Britain, in the late 1950s, a new tactical concept, based on brigade groups that would be largely mechanised, had been developed to replace the standard infantry division. The Australian battalions had been training to fight in South-East Asia within the framework of an organisation very similar to the now obsolete British standard infantry division. It was therefore considered that the army had to be reorganised and there were three alternatives: maintain compatibility with the British; develop its own organisation; or follow the United States’ lead by adopting a pentagonal structure which eliminated the brigade echelon and relied on large pentagonal battalions. The Americans had turned to a pentagonal structure known as the ‘pentomic’ organisation in 1956.9 The Chief of the General Staff finally selected the third alternative in December 1959 for a number of reasons.

With the formation of the 1st Infantry Brigade Group in 1957, greater emphasis was put on all-arms cooperation and conventional warfare. The photograph shows troops of 2 RAR advancing in a cloud of dust beside a Centurion tank of the 1st Armoured Regiment during an infantry–tank cooperation exercise known as Exercise Sabrefoot (AWM photo no. BEN/114/HQ).

One feature which commended itself to the political and military decision makers was that the pentomic ‘battle group’ (a battalion with supporting arms under command) was a force large enough to be noticed, to ‘count for something’ politically and militarily. The provision of anything smaller for a commitment overseas would have been militarily unimportant and politically embarrassing. The battle group was also larger than the traditional Australian battalion, which some servicemen considered to be too small to be effective in jungle operations. It had further been suggested that the United States could guarantee to supply in bulk what Australia needed in terms of expensive military equipment whereas the United Kingdom could not. The need for Australia to be compatible with a future ally had been an important factor in the decision-making process. As Sir Ragnar Garrett, Chief of the General Staff from 1958 to 1960, pointed out in 1963, ‘it [was] only commonsense that our equipment should be similar to, or at least compatible with [the United States]’. The 1960 pentropic plan was seen as representing a genuine attempt at modernisation and integration with our major ally.10 Another significant factor was that Garrett had been faced with the need to obtain more funds for the army, which at the time was still using worn-out Second World War weapons, equipment and vehicles. According to General Sir Arthur MacDonald (commanding officer of 3 RAR from March 1953 to February 1954, and Chief of the General Staff in the 1970s) the pentropic restructuring did achieve this result; and Garrett may not have otherwise been able to obtain the necessary funds from parliament. Furthermore, from the army’s viewpoint it ensured that the money saved from the abolition of national service training did not go to navy or air force projects. There was a feeling that a ‘reorganisation’ would invite a lot more interest and support than mere cutbacks in national service, and this certainly appears to have been the case.11

The Minister of Defence, Townley, officially announced the reorganisation of the field force along ‘pentropic’ lines on 29 March 1960, and the February 1960 edition of the Australian Army Journal was devoted solely to explaining the workings of the new organisation. In the introduction it was claimed that the organisation was being implemented ‘to reduce the vulnerability of our field forces to nuclear attack, and to improve their capacity to meet the particular requirements of a war in South-East Asia’. It was supposedly a ‘lean, powerful, versatile organisation, readily adaptable to any type of operation in which it is likely to be involved in South-East Asia’. The army subsequently began field tests to determine whether or not the organisation would be the best possible for its requirements. Officers responsible for assessing the organisation’s efficiency on exercises were exhorted in the journal to match the flexibility inherent in the organisation with a flexibility of thought on their part.12

The pentropic division’s establishment strength was approximately 14,000 as compared with 13,000 in the previous jungle division. It was envisaged that on active operations the forward echelon of divisional headquarters would normally be deployed in two locations at once, that is, at both the main and the task force headquarters, to reduce the possibility of both headquarters being destroyed in a single atomic attack. It was further planned that the divisional commander would establish a small tactical command post in any rapidly moving situation.

These changes gave the commander greater flexibility in grouping for combat, allowing him to tailor the various divisional elements to meet the specific requirements of his plan. The five infantry battalions, the armoured regiment, the reconnaissance squadron and the five artillery regiments could be combined in varying proportions into battle groups, along with engineer, aviation and service elements as required.

The concept of a battle group was the central innovation associated with the pen-tropic division. Effective control was to be gained by grouping the various elements under the command of the infantry battalion commander (a colonel), who would act as the ‘battle group’ commander (with a lieutenant colonel as his second-in-command). This structure was, however, to prove more cumbersome than the planners had envisaged. Infantry battalion commanders such as Colonel C.M.I. Pearson, commanding officer of 1 RAR from July 1962 to May 1964, were later to testify that the pentropic organisation failed precisely because of the problems of command associated with such a large and diverse organisation as the battle group.13

Numerically each new battalion was equal to about one and a half of the old battalions but with more than twice the firepower, as each now contained 80 assault sections as opposed to the original 36. There were now an extra 76 infantry assault sections in the new division, bringing the total to 400. The larger battalions supposedly made for extra manoeuvrability, offensive action and protection, while allowing for the customary loss of manpower on operations. When the battalions were formed into battle groups, (including supporting arms such as armour, engineers and artillery), they provided a hard-hitting and relatively self-contained force for any independent operations, or as a contribution to an allied force.14

With the abolition of the brigade headquarters, the battalion headquarters was augmented to include an extra three staff officers headed by the executive officer (a lieutenant colonel). The executive officer and his staff, together with the support company and administration company commands, stood in the place of the original brigade headquarters staff and provided a more rapid dissemination of information than previously. The smaller size of the headquarters compared to the old brigade headquarters facilitated easier concealment, movement and defensibility than previously. On the other hand, it was comparatively more cumbersome and difficult to conceal than the old battalion headquarters.15 The most fundamental of all the changes were within the rifle companies. The pentropic battalion had five of these, each of which was comprised of four rifle platoons, a weapons platoon and a headquarters commanded by a major. Each of the platoons contained four sections. (The previous structure had contained only four rifle companies, each of three platoons, with each of these made up of three sections.)

The introduction of the pentropic division in 1960 resulted in the conversion of 2 RAR and 3 RAR from their standard establishment of some 800 men to pentropic battalions, each of 1300 men. When supporting arms were added a battle group numbering about 1800 men was formed. This photograph shows the 2 RAR battle group parading through Sydney past the Governor-General, Lord De L’Isle, in 1961. Parades in steel helmets and webbing were common in this period (AWM photo no. LES/159/HQ).

Supporting weapons (including two mortars and three medium anti-tank weapons) were removed from the rifle platoons and placed in the weapons platoon, and an extra assault section was added in their place. This gave the platoon commander increased flexibility and enabled him more easily to achieve depth in both offensive and defensive operations. The assault sections remained basically unchanged, still carrying FN 7.62 mm rifles; however, they did gain the 7.62 mm M60 general purpose machine-gun, two of which were also carried by company headquarters. This meant that platoon commanders were responsible for a powerful and large force that could operate with greater dispersion and more flexibility than before, but their relative inexperience meant that controlling their command, particularly in thick scrub, was difficult.16 Company commanders were, in general, content with the larger sized companies and the role apportioned to them. According to Pearson, they had a ‘powerful little force to handle, with greater flexibility (due to the larger number of sub-units) and more autonomy’.17 From the battalion commander’s point of view matters were more complex.

The majority of officers seemed to enjoy the additional responsibilities that came with the increased span of command in the organisation; however, there were also a number of problems associated with it. Colonel W.J. Morrow pointed out that ‘a commanding officer needs personal contact . . . it’s not enough to just pass orders over the radio—they want to see your face’. Colonel Pearson considered that ‘the span of control was not right . . . the battle group commander lost touch with the bottom because he had to deal with two or three thousand people. I don’t think it would have ever worked because of that.’ On the other hand, Pearson and Morrow wrote in 1964 that a unit to unit comparison did not ‘really hold water, because the battle group commander thinks differently from the old battalion commander.

He commits his sub-units somewhat like the brigade commander did his units, knowing their capacity is almost double that of the old companies.’18 Major General A.L. Morrison (GSO 2 in 1962–63 and then executive officer in 1964 to Colonel Pearson commanding 1 RAR) has stated that the organisation was very difficult to understand initially, yet when mastered it became quite easy to operate. Its strength was that the five companies could perform ‘meaningful’ tasks, as there was now ‘a proper reserve’ as well as an immediate exploitation force for a deliberate attack. The battalion could now protect a defensive position and still have four companies available for other deployment. Furthermore, in an advance the battle group commander now had the means of protecting his echelons and soft-skinned vehicles, or picketing their route, without seriously affecting the balance of the rest of the force.19 The support company of each new infantry battalion was also reorganised to consist of an anti-tank platoon, an assault pioneer platoon, a mortar platoon and a signals platoon. The machine-gun platoon was eliminated, as the new M60 machine-guns allotted to each rifle company as replacements for the old Bren guns were also considered adequate to fulfil the role previously performed by the old Vickers machine-guns. This was in spite of the fact that the new gun’s range was 800 metres less, and that its rate of fire per minute, 1500 rounds, was less than the Vickers. An anti-tank platoon was introduced, using 120 mm recoilless rifles, which were later changed to the 105 mm recoilless rifles, able to immobilise enemy tanks at ranges up to 1200 metres. This platoon was designed to supplement the 70 mm rocket launcher capability of the assault (rifle) sections.20 The assault pioneer platoon was increased from four to five sections (one per rifle company) each being equipped with a motor digger, a chain saw, and explosive foxhole diggers with the single bulldozer and tipping truck being eliminated. The mortar platoon remained unchanged, with the exception of the 3-inch mortar, which was replaced by an 81 mm weapon with a range of 3600 metres as opposed to the 2500 metres of the original. The signals platoon was reduced in strength by passing responsibility for line maintenance to the companies, and for the unit signal centre to the signal troop, which was allotted to support the battalion from the divisional signals regiment.

The battalion’s entire communications system was significantly improved at this time as a result of the introduction of the new VHF PRC series of portable radios (PRC 9, 10, and 25). These enabled commanders at all levels to have a greater degree of flexibility and control than was previously possible. Although it was contended that the new radios made the pentropic organisation possible, many felt that the communications technology did not match the requirements of these big battalions operating in a dispersed setting. The range of the VHF signals equipment, for instance, was about fifteen kilometres in jungle terrain while the battalion could be spread out over a 30-kilometre area, making it necessary for orders to be relayed.

The administrative company received six wheeled ambulances (to help with the expected longer turnaround time for casualty evacuation in dispersed operations), a bearer officer, and all the hygiene dutymen, who went to the medical platoon. Furthermore, the large stores holding in the quartermaster’s platoon was transferred to the ordnance field park, thus eliminating the need for a B echelon for the supply and maintenance of the battalion.

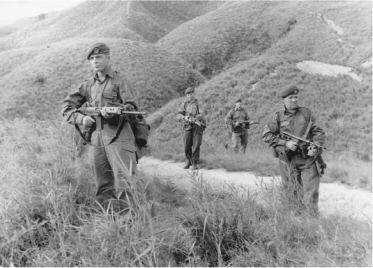

From November 1960 until September 1964 the SAS Company at Swanbourne, Perth was part of the Royal Australian Regiment. In May 1964, the SAS Company joined a major SEATO exercise, Exercise Ligtas, on the island of Mindoro in the Philippines. The photograph shows members of the company on reconnaissance during the exercise wearing red berets with RAR badges (AWM photo no. LES/159/HQ).

One outcome of the reorganisation was the recommendation from the Director of Infantry that the SAS Company be shown as a unit of the Royal Australian Regiment. He argued that the infantry (and major) component of 1st SAS Company relied wholly for its personnel on the RAR and that all ranks normally transferred to a battalion of the regiment when moving out of the company for promotion or any other reason. This change was resisted by the SAS but was approved by the DCGS on 14 November 1960. The company therefore changed its beret badge from infantry corps to that of the RAR. The activities of the 1st SAS Company (RAR) have been described in the history of the Australian Special Air Service.21 The SAS parted ways with the RAR in September 1964 when a separate SAS regiment was formed.

Another outcome of the reorganisation, and the decision announced in November 1959 to terminate the National Service Training Scheme, was the radical restructuring of the CMF and the integration of the CMF and the ARA. Out of the 31 standard infantry battalions and nine brigade headquarters only eight reconstituted pentropic battalions remained, organised into state regiments bearing the ‘Royal’ prefix.22 For the first time regular and CMF units were required to work closely together, and General Sir Arthur MacDonald recalled that the reorganisation had ‘the effect of bringing the Regular Army and the CMF closer together . . . as divisional supporting arms, such as engineers and signals were integrated at unit level’.

However, as Major General P.A. Cullen, CMF Member of the Military Board from 1964 to 1966, argued, ‘integration . . . was clumsily done, and was an additional factor causing [CMF] disillusion, discontent, disruptions and resignations’.23 The disillusion felt in many quarters of the army was accentuated by an unexpected report on 3 June 1961 that the United States Army was abandoning the pentomic organisation.24 But despite the fact that the army would once again possess an organisation that was incompatible with that of its allies, the Australian Military Board argued that ‘no new factors have arisen in Australia which make necessary any changes in basic structure of the pentropic division and none are proposed. Study and evaluation will continue, however, with the aim of improving the pentropic organisation.’ Three years of further study and evaluation provided hard evidence that the suspicions of many regarding the pentropic establishment were justified. According to Sir Arthur MacDonald, General Wilton, then Chief of the General Staff, agreed in late 1963 that change was needed. But Wilton realised that ‘in the light of all that had been said in support of the pentropic organisation and the equipment orders which had been placed as part of its implementation, it would not be practical at that time to revert to a “three brigade” division. That would have to be a matter for the future, but he did not doubt that the change would come about. In the meantime it was the army’s job to get on with what it had and make it work as best we could.’ Thus it was the responsibility of the battalions to do their best under these circumstances.25 It was not until 1 RAR returned from Malaya in October 1961, having been relieved by 2 RAR, that it was placed on the pentropic establishment. The battalion, now based at Holsworthy, remained on the pentropic establishment, with a strength exceeding 1300, until the reorganisation in 1965. During this time its training included major exercises every year such as Sky High and Nutcracker. 1 RAR also provided the House Guard at Government House, Canberra, during the Royal Tour of 1963. Exercise Sky High was conducted in the Colo–Putty Training Area in October and November 1963, under the command of Brigadier A.L. MacDonald, the Deputy Divisional Commander, with the visiting Royal Ulster Rifles taking part. The year of 1963 marked a change in emphasis toward the development of doctrine and tactics for counterinsurgency operations.

The major exercise in 1964, Exercise Longshot, was held during September and October in the Tianjara area south-west of Jervis Bay. This was a joint tri-service exercise slanted at the logistic and administrative aspects of the maintenance of a force overseas. For 1 RAR under Colonel Don Dunstan (commanding officer of 1 RAR May 1964 to February 1965) this was largely a company training exercise with a firepower demonstration. By then, according to MacDonald, the pentropic organisation was ‘on the way out’ and therefore the exercise was not of much consequence. As Colonel Pearson, commanding officer of 1 RAR from July 1962 to May 1964, noted, ‘the main problem was the size of the battalion and the extra commands, which made it almost impossible to command every single element’.

In mid-1960 2 RAR, based at Holsworthy, was reorganised along pentropic lines while under the command of Colonel K.R.G. Coleman. The former commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel A.S. Mann, became the battalion’s executive officer.

2 RAR was warned for service in Malaya in 1961 and therefore had to be reorganised on the tropical establishment (TE). This meant it would include four rifle companies, rather than the five in the pentropic battalions, so as to be compatible with the British and New Zealand units that were part of the BCFESR. The battalion left for Malaya in October 1961 and returned to Australia in August 1963, when it was, once again, reorganised on the pentropic establishment. This time the battalion was based at Enoggera and was under the command of Colonel O.D. Jackson.

In mid-1964, at Tin Can Bay in Queensland a major battle group exercise— Crusader—was held, employing about 3000 troops (including a squadron of Centurion tanks), under the command of Colonel Jackson, the 2 RAR battle group commander. According to MacDonald, then the deputy commander of the 1st Division, ‘it was patently obvious that the battle groups with their supporting arms and services were far too unwieldy and (that they) prevented, or at least hindered effective tactical control of the battle group commander . . .’.26 In July 1960, 3 RAR, based at Enoggera following its return from Malaya in October 1959, was organised on the pentropic establishment. Sergeant Barry Caligari recalled that ‘almost overnight the battalion changed from a big family in which most faces were familiar to a large, cold, forever changing organisation, where faces were familiar only in one’s own company’.27 Training as a battalion and a battle group was carried out culminating in major exercises in 1961 and 1962. One of these, Exercise Nutcracker, was a conventional war exercise involving nearly 8000 troops, based on an advance on three axes. It was held jointly with 1 RAR in the Colo–Putty area and was commanded by HQ 1 Task Force. In this exercise 3 RAR operated quite differently to 1 RAR. 3 RAR moved in two-company groups, with the fifth company and administration company in the echelon area.

On the other hand, the commanding officer of 1 RAR believed that the companies were strong enough to operate independently and so the companies operated separately. Problems arose as sub-units, including the artillery batteries, had to leap-frog to fire positions using a single track as their axis, and this created extreme traffic control problems. Colonel W.J. Morrow, commanding officer of 3 RAR from July 1960 to December 1962, observed that ‘we suddenly had a large number of vehicles which we had not experienced before. Having worked out our road movement and vehicle control, we suddenly found that when in the tropics, the last thing we wanted was a large number of vehicles. It was cumbersome in close country.’28 The military police were under command during the exercise and the watchword was traffic control.

During this period 3 RAR also conducted a number of other activities. In early 1961, for instance, company groups conducted recruiting drives throughout Queensland. Later in 1961 companies undertook armoured-infantry training at Puckapunyal, Victoria, and during both 1961 and 1962 the battalion participated in Army Week celebrations in Northern Command, involving mechanised parades, assault river crossings and displays involving the use of helicopters. Then in 1963 E Company moved to Cape York peninsula to take part in Exercise Blowdown, an exercise simulating the effects of an atomic blast and the subsequent fallout under tropical conditions. Soon after this exercise the battalion was reorganised on the TE establishment and in July and August was airlifted to Malaya for its second tour of duty there, this time under the command of Lieutenant Colonel B.A. McDonald.

To alleviate the problem that had arisen with the rotation of the pentropic battalions in Australia, a new battalion, 4 RAR, was raised at Woodside in 1964 on the tropical establishment. Each time a battalion was sent to Malaya it had to change from the pentropic to the tropical establishment, causing unnecessary turmoil and disruption to unit cohesion, and it was hoped that the creation of 4 RAR would solve the problem. The decision to raise the battalion had been made in 1963 and the raising instructions stated that the battalion was to be at full strength by 31 March 1964. The first regular battalion raised in Australia, its inauguration parade was held at Woodside Barracks on 1 February 1964 with Lieutenant Colonel D.S. Thomson as the first commanding officer. The next eighteen months were spent at Woodside in preparation for the relief of 3 RAR in Malaysia.

The End of the Pentropic Organisation

The pentropic organisation was not introduced with a great deal of preliminary assessment or testing through map and model exercises, and this lack of foresight resulted in much frustration and disappointment within units; it risked the very preparedness it had sought to gain. One of the stated advantages of the pentropic organisation was the supposed increase in mobility afforded by the new organisational structure. Its simplified vehicle and weapon families were intended to reduce administrative overheads, making it easier to move by land, air or sea. In practice, however, the pentropic division was not equipped with an APC lift capability of even one battalion until 1964. Instead, each infantry battalion was allocated 70 vehicles (Land Rovers, weighing three-quarters of a tonne each) which, while increasing the battalion’s road lift capability, tied it to the main roads, and reduced the commander’s off-road flexibility. The problem was further exacerbated by the fact that, as a result of the increase of the numbers of vehicles in the battalion, divisional wheeled transport resources became increasingly hard to obtain. Consequently, Land Rovers were often overloaded (particularly those assigned to the mortar platoon) as there were no trucks immediately available.29

According to Brigadier Morrow, the army was trying to employ a cumbersome organisation, designed for open atomic conditions, in a tropical environment where it was constrained by the roads and subject to ambush. Moreover, although it was not so difficult in open country with plenty of roads, the problem of command and control of the pentropic battalion in a tropical environment was its downfall.

General MacDonald, Commandant of the Jungle Training Centre from March 1959 to July 1960, recalled that ‘we, at Canungra, could not visualise its ready application for jungle warfare’. And whatever its virtues might be in a nuclear situation, ‘the pentropic organisation was not the best for conditions in which the Australian Army was likely to fight’.30 Major General D. Vincent, Director of Staff Duties in 1960, believed that the pentropic organisation was not successful because of four factors: commanders failed to see the significance of the five big battle groups and the independence of the five-rifle-company battalion; they failed to regard the battle groups as small brigades rather than big battalions; they failed to exploit fully the new communications equipment (which made the pentropic concept possible); and the ambivalence of the Chief of the General Staff, Lieutenant General Pollard, who never gave the necessary instruction to develop a light scale pentropic division for operations against insurgencies. In late 1964 the need for a light scale division was highlighted as a factor contributing to the need for another reorganisation.31 The Australian pentropic organisation had disrupted the promotion and command posting prospects of infantry corps officers, as it removed the opportunity for lieutenant colonel level command experience. Streamlining of positions associated with the pentropic reorganisation and the elimination of the National Service Training Scheme was further publicly blamed, with some justification, for the forced retirement of eight senior army officers in 1960. It was another factor contributing to growing discontent with the pentropic establishment.32 By late 1964 the Chief of the General Staff, Lieutenant General Sir John Wilton, had decided that there were four main factors justifying a reorganisation of the field force. First, under the new strategic basis the 1st Division was more likely to operate in two separate strategic areas than fight as one cohesive formation. Second, the emphasis on the Cold War implied a need for smaller, lightly supported, infantry battalions. Third, the constantly increasing availability of tactical air support allowed an overall reduction in road transport. And fourth, there was the possibility, although by no means assured, of an alleviation of the manpower problem through some form of selective service. Wilton went on to point out several ‘weaknesses’ with the pentropic division, including ‘the lack of intermediate headquarters between division and battalion’; and the overly wide span of control at various levels.33 At the sixth Quadripartite Infantry Conference in 1964, the problem of interoperability of infantry units of the American, British, Canadian and Australian (ABCA) armies was examined. As a result, the United States (with its three-rifle- company battalions) and Australia (with its five-rifle-company battalions) were invited to examine the concept of a battalion organisation containing four rifle companies, following the pattern of both the United Kingdom and of Canada. Pressure for a reorganisation was mounting.34 In the end, perhaps one of the most significant factors leading to the elimination of the pentropic organisation was that, in General Wilton’s words, ‘it’s not the size of the battalions that counts: it’s the number’. Australia was in need of a greater number of units so that it would be capable of deploying independent forces to a number of different places at any one time. The change from the pentropic to the triangular (Tropical Warfare—TW) division (in addition to the reintroduction of national service) enabled the size of infantry battalions to be reduced to approximately 800 men and permitted an additional four regular battalions and at least six CMF battalions to be raised.35 The abandonment of the pentropic organisation followed the completion in November 1964 of a report by Major General J.S. Andersen, Commander of 1st Division, to review the army’s field force organisation. The Andersen Report saw the infantry division reverting more to the style of the triangular division with a cavalry regiment, three field regiments, three field squadrons of engineers, a completely redesigned signals regiment and ten infantry battalions, controlled by three task force (or brigade) headquarters. The report also flagged, for the first time, the need for an aviation wing to be organic to the division, comprising a light aircraft squadron and a utility helicopter squadron, commanded and manned by army personnel.36 The subsequent Military Board review of the army’s field force organisation of 11 December 1964 stressed that ‘the announcement of the change must be handled with great care’. Such care was required ‘to avoid criticism that the Army had not been able to make up its mind and that the change was a retrograde step’. This was one reason the army favoured using the term ‘task force’ to avoid the use of the term ‘brigade’, a term analogous to earlier organisations. Major General Falkland recalled that ‘we all sighed with relief ’ when the army reverted to the standard (triangular) organisation.37 The Australian ‘Task Force’ was to be a balanced force, based on a nucleus of two or more battalions and commanded by a headquarters supposedly capable of operating indefinitely in an independent role (although presumably still within the division). Low priority was given to the division fighting en masse in any limited war engagement. The new tropical warfare organisation was oriented towards counter-revolutionary warfare and the division was organised to meet an operational requirement for an air mobile formation. It relied heavily upon RAAF air transport support to enable it to realise its full potential. As part of the three-year defence program of 1962–63 to 1964–65, eighteen Caribou aircraft, eight heavy lift helicopters, 24 Iroquois helicopters and twelve C–130E Hercules were acquired for this purpose.38 The eventual composition of the new division included ten battalions (although one battalion was allocated to the division for protection tasks) and an armoured cavalry regiment (previously a squadron). The armoured regiment became part of corps troops and the utility helicopter squadron was retained by the RAAF for the time being.

The Andersen Report also made a number of other recommendations, which were implemented, including: the reduction of the divisional artillery to three regiments, each of three batteries containing six guns (totally 54 guns); the reduction of the infantry battalion to 841 all ranks; the restriction of the number of vehicles in a battalion to 29; the reversion of the rifle company to three platoons and a small headquarters (basically reverting to the organisation that preceded the pentropic organisation); the reduction of the platoon to three sections (as the maximum that a platoon commander could efficiently command); the addition of one M79 grenade launcher to each section; and the reduction of the mortar platoon to six 81 mm mortars.39 Most military personnel welcomed the demise of the pentropic organisation in December 1964. The United States’ abandonment of the pentomic organisation had helped to set Australians’ minds against the pentropic division from the earliest stages. And since Australia was equally likely to be fighting alongside the British in the BCFESR (particularly with the onset of ‘Confrontation’ with Indonesia), as with the US, Australia’s compatibility with the UK had become a serious matter. There had also been constant difficulties relating to control and supply of the pentropic organisation. In the minds of many, there was a need to revert to an organisation with which they would ‘feel more comfortable’, and which would be more useful in terms of Australia’s foreign policy.

As the army moved away from the pentropic organisation, a selective national service scheme was introduced. This scheme was unlike its predecessor of the 1950s in that the conscripts were to serve with the regular army and not the CMF.

Throughout 1964 it had been noted that the army was losing manpower at an alarming rate while its commitments were increasing. It was imperative that, for the problems of the previous scheme to be avoided and the army’s capabilities to be maintained, there should be a limited call-up only, with two years’ service. Moreover, everyone called up had to be available to be sent overseas if the scheme was to be of any value. The reintroduction of national service and the abandonment of the pentropic organisation resulted, in the view of Major General Stretton (Chief of Staff Australian Force, Vietnam from April 1969 to April 1970), in an organisation ‘eminently suitable for the war in Vietnam’.40 The pentropic experiment occurred at a time when there was a low level of operational commitments and the risks involved in such a reorganisation may not have been taken had there been a greater demand placed on the regiment during the early 1960s. The period from 1960 to 1965, however, was marked by a long period of training, which allowed infantry officers and soldiers to develop the necessary skills whereby the army could expand rapidly in 1965 without a serious lowering of standards. It was a period in which the manpower base of trained soldiers was developed prior to the Vietnam commitment. For example, a soldier who joined a battalion as a private in 1960 may have spent five years’ training at either Enoggera or Holsworthy by 1965.

Despite the disruption of the pentropic experiment, for the regiment the early 1960s had been a period of consolidation. Although the battalions had rotated, many soldiers accepted Enoggera and Holsworthy as home and the local community had become used to their presence. At last the army was coming to grips with fostering, maintaining and supporting a long-service regular infantry force.

As a result of the government’s initiative, on 1 March 1965, 1 RAR was reorganised on the tropical warfare establishment and gave up half of its officers and men to the newly formed 5 RAR in the same lines at Holsworthy. 2 RAR, still based at Enoggera, was reorganised on 6 June 1965 and many of its members were transferred to form 6 RAR. 1965 marked the end of a chapter in the history of the regiment, as the pentropic establishment was abandoned, and the beginning of a new one, as a selective national service scheme was introduced, as the regiment was expanded from to four to seven battalions, and as 1 RAR went to Vietnam in May 1965. But before describing the expansion and the operations in Vietnam, the story must return to Malaysia, where a battalion of the regiment, largely immune from the reorganisation in Australia, was still serving after the end of the Emergency in 1960.