9 The Build-Up Vietnam, 1965–67

Bob Breen

Between June 1965 and March 1972, sixteen battalions of the Royal Australian Regiment served in action in South Vietnam. The first seven battalions each had two twelve-month tours, while 8 RAR and 9 RAR each had one. During this period, 14,325 Australian infantrymen served in Vietnam, and the overwhelming majority of these were with the battalions of the regiment. Of the 415 soldiers who died on active service, 323 came from the regiment. As far as Australia was concerned and within the context of the price paid, it was an infantryman’s war. This chapter covers the operations of 1 RAR in 1965–66, 5 RAR and 6 RAR in 1966–67, and 2 RAR and 7 RAR in the last half of 1967.

For the belligerents in Vietnam, 1965 was a pivotal year—one of important decisions and a rapid increase in American and allied military commitments. This was the seventh year of the Second Indo-China War.1 The Republic of North Vietnam was sending regular army formations into the central provinces of South Vietnam to cut the country in two in an effort to force the collapse of the beleaguered Saigon government. In anticipation of the arrival of these North Vietnamese forces, Viet Cong guerilla units, under the direction of the National Liberation Front, an organisation directed from North Vietnam, had begun to consolidate into approximately 1000-strong main force regimental and 4000-strong divisional-sized formations.2

North Vietnam was pushing South Vietnam to the abyss of political and military collapse in order to reunite Vietnam under communist rule.3 Following military advice, President Lyndon Johnson authorised the bombing of North Vietnam and the despatch of a brigade of Marines and an airborne brigade from the Okinawa-based US Pacific Area Reserve to Da Nang and Bien Hoa air bases respectively in April and early May 1965. These formations would protect the air bases, find and fight the Viet Cong and spearhead a massive American escalation of the war. Australia decided to support President Johnson. On 13 April the Menzies government offered an infantry battalion group and announced acceptance of this offer to the United States as a request from the South Vietnamese government on 29 April.4 Prime Minister Robert Menzies promised rapid deployment. In a manner similar to 1950 when he ordered 3 RAR to Korea, his government left little time for preparation.

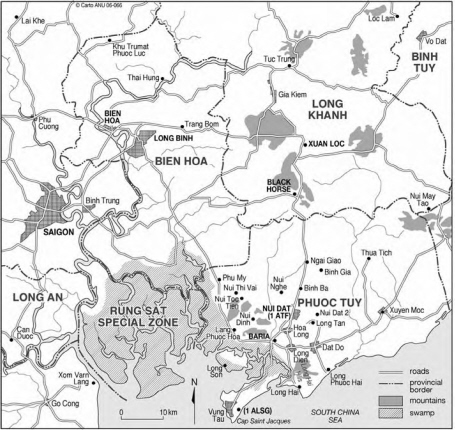

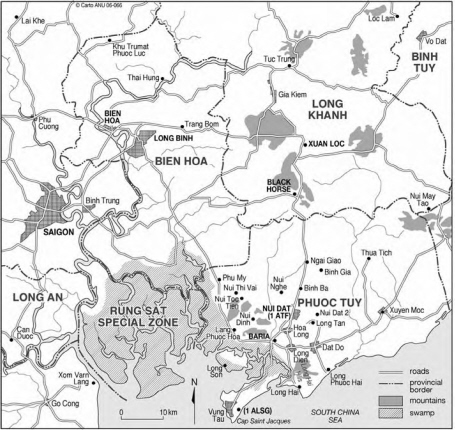

MAP 9: Area of Operations in Vietnam. From June 1965 to June 1966 1 RAR was based at the US air base at Bien Hoa. It patrolled near the base but eventually operated throughout Bien Hoa province and also took in the surrounding provinces. In June 1966, the 1st Australian Task Force was established at Nui Dat in Phuoc Tuy province. The first battalions, 5 RAR and 6 RAR in 1966–67, and 2 RAR and 7 RAR in the second half of 1967, operated almost exclusively in Phuoc Tuy. During 1968 and the early months of 1969, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7 and 9 RAR operated across the borders in Bien Hoa and Long Khanh, and during the VC offensives in January–February and May–June 1968 operated astride the northern borders of Bien Hoa. From mid-1969 to late 1971 operations were generally restricted to Phuoc Tuy with some operations along the neighbouring borders.

Ian McNeill, the official historian, and Bob Breen, author of a history of 1 RAR’s first tour, vary in their views about 1 RAR’s preparedness for service in Vietnam.5 The army had not trained 1 RAR in combined arms tactics employing armour, helicopters and combat engineers, or artillery and close air support.6 The battalion had not conducted any live firing range practices of its sections, platoons or subunits, or employed artillery fire or close air support in the past twelve months. Blank ammunition was in such short supply that machine-gunners had to simulate firing their weapons by operating wooden First World War gas warning clackers during training in infantry minor tactics.7 Some weapons, communications equipment and personal clothing and equipment were obsolete.8 The 1st Australian Division in 1914 and 6th Australian Division in 1940 were better armed and equipped by the standards of their times than 1 RAR was in 1965.

After a rushed period of training and administration, 1 RAR joined the newly arrived 173rd Airborne Brigade (Separate) at Bien Hoa air base as its third manoeuvre battalion during the first week of June 1965.9 Located 40 kilometres north of Saigon, the Viet Cong had attacked Bien Hoa air base with mortar fire in November 1964, causing millions of dollars worth of damage to aircraft and facilities. General William Westmoreland, the American commander in South Vietnam, ordered the brigade to protect the air base from a similar attack now that Operation Rolling Thunder, the American air offensive against North Vietnam, had begun. As the Australians arrived by air and sea, the North Vietnamese began their thrust into the Central Highlands and several towns in the central provinces. Westmoreland put the 173rd on full alert in anticipation of deploying them at short notice to support South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) formations opposing the North Vietnamese.

The first battalion to be deployed to Vietnam was 1 RAR, which began to arrive in the first week of June 1965. It became part of the US 173rd Airborne Brigade, and a soldier from that brigade stands by as troops of 1 RAR step ashore from a Vietnamese landing craft after disembarking from HMAS Sydney (AWM photo no. HIN/2/VN).

The 173rd was a unique 3000-strong all-arms independent formation, trained to deploy quickly by air and to parachute in, if necessary, to anywhere in the South-East Asian and Pacific region, and to use firepower and bold tactics to ‘get in, get the job done and get out’. Its organisation included two airborne battalions with artillery, engineer and armoured units and sub-units integrated into its organisation.10 Initially, Australian officers and NCOs joined the paratroopers on patrol around Bien Hoa. They soon realised that American and Australian patrolling tactics and techniques were very different. The Americans patrolled in an aggressive and obvious manner—like a noisy hunting party—eagerly seeking battle. Their smoking, talking, firing into suspicious areas, and wearing of the bright red, white and blue airborne shoulder patch, said to the Viet Cong, ‘You know where we are, take us on, and pay the price.’ The Australians patrolled silently and carefully so as not to give away their location and to engage the enemy on their terms. They were saying to the Viet Cong, ‘You will never know exactly where we are, but we will find you and kill you.’

The first operation into a Viet Cong redoubt centred on the intersection of Binh Long, Phuoc Long and Bin Duong provinces known as War Zone D, early in July 1965 typified many that were to follow. Artillery and bombs set the scene by pounding a number of landing zones before troops arrived. The paratroopers jumped out of the helicopters and concentrated into large hunting parties and swept forward along roads and tracks. The Viet Cong ambushed several American companies, but they had not counted on the courage of the paratroopers at close quarters. The Americans charged headlong into ambushes, took casualties, but were able to inflict heavy casualties on the Viet Cong on every occasion, assisted by artillery fire, helicopter gunship fire and bombs and napalm dropped by jets. In one action, an approximately 800-strong Viet Cong force killed or wounded a third of an American company. During this battle, the paratroopers, supported by American gunners and jet and helicopter gunship pilots, inflicted substantial casualties on the ambushers.11 In contrast, the Australians also arrived by helicopter but then dispersed into smaller platoon-sized patrols and combed their areas meticulously and quietly, avoiding roads and tracks. The Viet Cong were not able to set ambushes because they did not know where the Australians were and could not predict their movements. Because of inadequate intelligence and their dependence on noisy helicopter arrival, preceded by bombardment, the Australians were unable to find and fight sizeable Viet Cong units. Thus, they and the Viet Cong were in a tactical stand-off, neither side able to bring the other to battle on their own terms.

Brigadier General Williamson summarised his attitude to Australian tactics later:

The Aussies taught us a lot about small unit operations and we taught them quite a lot about the co-ordination of large-scale operations. Our job in those days was not to pussy foot around the jungle hoping to bump into the Viet Cong. Our job was to get in there and bring him to battle—to keep him off balance, show the ARVN [South Vietnamese Army] what to do and clear areas for the build-up of other American units.12

For the next two months, 1 RAR defended Bien Hoa air base while the remainder of the brigade fought in the highlands. During that time, the Australian patrol program succeeded in reducing Viet Cong activity around the air base to an all-time low. The paratroopers successfully kept the North Vietnamese at bay in the central provinces, moving around in helicopters, eagerly seeking battle, and bombing and shelling suspected enemy locations.

Meanwhile, back in Australia, large numbers of national servicemen joined 5 RAR and 6 RAR in September 1965 after their recruit training. The regulars began to train them for operations in Vietnam, although the government was reluctant to make a public announcement on when they might fight there. Lieutenant Colonel John Warr, commanding 5 RAR, assumed his battalion would relieve 1 RAR in June 1966 after the battalion had served in Vietnam for twelve months.

Meanwhile, the dangers increased in Vietnam. After two weeks of inconclusive operations near Ben Cat, the 173rd swept into another Viet Cong redoubt called the Iron Triangle on 8 October 1965. Corporal Lex McAulay summarised what happened in his diary: ‘Constant stream of casevacs [casualty evacuations by helicopter]. Companies that went out to the north and west came in savage and blood thirsty—losing blokes to bloody booby traps [typically trip wires that detonated anti-personnel mines], never coming to grips with the VC, who were constantly sniping . . . Any VC that confronts this mob will be torn from limb to limb.’13 In the Iron Triangle operation, 1 RAR lost two killed and 36 wounded, with many of the wounded maimed for life and having to have limbs amputated.

Brigade records show that anti-personnel mines caused 90 per cent of the nineteen deaths and 110 woundings during the operation.14 The brigade was unable to draw the Viet Cong into battle, but did succeed in patrolling through the area before the arrival of the US 1st Infantry Division.

For the next operation, the Viet Cong stood and fought to defend their supply lines. On 4 November 1965, the brigade flew by helicopter to an area that was the junction between the Ho Chi Minh Trail that ran along the Cambodian side of the South Vietnamese border and the main communications and supply routes to War Zones C and D in South Vietnam. The Viet Cong 271st Main Force Regiment protected this area in a series of well-established bunker complexes.

On 8 November, the 1/503rd Battalion walked into a U-shaped bunker system and for the next three hours engaged in savage and desperate close quarters combat. The Viet Cong not only fired at them from trenches but also counterattacked them repeatedly, supported by machine-gun fire from prepared positions. The Viet Cong employed new tactics. They came in close to the Americans, inside artillery and mortar range, in order to negate American advantages in firepower. In the words of Ian McNeill, ‘the Viet Cong held the waist belt of 1/503rd Battalion with one hand and punched hard with the other’. However, once again, accurate American and Australian artillery and mortar fire falling on troops located behind the forward edge of the fighting swung the battle in favour of the paratroopers. By late afternoon, the Viet Cong regimental commander ordered his men to abandon the bunkers. The paratroopers reported that 400 enemy corpses lay on the battlefield and drag marks and blood trails verified that the Viet Cong had taken the bodies of more of their comrades with them from the carnage and evacuated hundreds of their wounded. The price: 49 paratroopers killed and over 100 wounded. The acknowledgement: a United States Presidential Unit Commendation. The accolade: ‘the largest kill by the smallest unit in the shortest time in the war to date’.15 The strategic dilemma: ‘no matter how many North Vietnamese regulars or Viet Cong guerrillas were wiped out, public opinion would eventually react against increasing American losses’.16 On the same day A Company, 1 RAR patrolled into a branch of the Ho Chi Minh Trail across the river from the American battle and moved up to a hidden bunker complex. After suffering two killed and four wounded in an opening burst of fire and the subsequent firefight, Major John Healy withdrew his men under the cover of artillery and mortar fire.17 Despite the heroic efforts of Sergeant Colin Fawcett, a platoon sergeant, the bodies of the two killed were not recovered.18 It was not until the next operation in late November that the Australians were able to bring the Viet Cong to battle on their terms. In a series of brilliantly executed battalion manoeuvres, 1 RAR captured the southern area of the La Nga Valley as a part of an operation to prevent the Viet Cong stealing a rice harvest (Operation New Life). The Australians suffered only light casualties and forced the Viet Cong to withdraw after inflicting heavy casualties on a main force company. They created the optimum conditions for success, using deception, stealth, initiative, and surprise to force the Viet Cong to abandon prepared ambush and defensive positions.19 In January 1966, 1 RAR continued to outmanoeuvre and outfight the Viet Cong. They assaulted a large Viet Cong headquarters complex in the Ho Bo Woods (Operation Crimp). The Americans hailed the capture of this headquarters, with its tonnes of military supplies and thousands of documents, as their first strategic intelligence victory of the Vietnam War.20 The Australians spent several days discovering more supplies and documents, while they destroyed an extensive three-level tunnel system.21 In Australia the men of 5 RAR read of 1 RAR’s exploits. Lieutenant Colonel John Warr, commanding 5 RAR, had visited 1 RAR and knew what was ahead. The army did not inform Lieutenant Colonel Colin Townsend, commanding 6 RAR, until January 1966 that 5 RAR and 6 RAR would deploy together to Vietnam by the end of May that year.22 As 5 RAR and 6 RAR prepared for their final field exercises before leaving Australia, 1 RAR came under the operational control of the US 1st Infantry Division in early February to protect an engineer battalion building all-weather roads connecting the forward brigades. By day, Viet Cong snipers were killing and wounding American sappers and, at night, small teams of Viet Cong sabotaged their plant, machinery and other vehicles and equipment. Each morning the Americans found new mines that the Viet Cong had laid overnight. General Dupuy, the commanding general, had selected the Australians personally because of their dispersed, aggressive patrolling attributes.23 On 22 February Lieutenant Colonel Alex Preece, who had taken over from Lieutenant Colonel ‘Lou’ Brumfield as commanding officer in December 1965, informed General Dupuy and an American brigade commander in the vicinity that a major attack was imminent. The Australians had killed and wounded several members of the Viet Cong’s 761st Main Force Regiment in overnight ambushes.

They were well equipped, carrying new AK-47 rifles and full loads of ammunition, rations, and medical supplies.24 By last light that day, Dupuy had rushed in one of his infantry battalions, reinforced with a platoon of M48 Patton tanks and a field gun battery, to defend the American brigade headquarters that was located next to the Australian camp.

Corporal Lex McAulay recorded his impressions of the first few seconds of the attack on the American headquarters in a letter he wrote the next day:

At 0225 hrs the most fantastic outbreak of firing from the tanks, guns and mortars, HMGs [Heavy Machine-Guns], grenades, LMGs [Light Machine-Guns], rifles— the lot—became a waterfall of firing, which died down to one or two guns and then swelled up again. Thousands and thousands of rounds—many of which were coming in our direction, cutting leaves and branches, plunking into the dirt, putting holes in hutchies [Australian-pattern two-man tents]. Great flaming .50 calibre tracers whizzing overhead.25

The Viet Cong regimental commander, who had been unable to conduct last-minute reconnaissance because the Australians had ambushed his pathfinders, sent assault wave after assault wave into the combined firepower of an American field artillery battery firing directly over open sights, and two platoons of tanks supported by a company of infantry. The carnage was horrendous as round after round of anti-personnel canister, flechette and splintex rounds scythed through the closely packed Viet Cong ranks.26 The Australians poured small arms fire into the flanks of what was turning out to be a futile and costly attack. The Viet Cong commander withdrew his shattered force before dawn and the inevitable arrival of marauding American helicopter gunships and jets.

Australian clearing patrols discovered 89 Viet Cong bodies and eleven wounded enemy soldiers forward of the Australian position just after first light. There were countless chunks of flesh, severed limbs and other human remains between the Australian and American positions. Red pulp, running with blood and latex, covered the shredded rubber trees that were still standing. The Americans bulldozed over 150 Viet Cong bodies into a B–52 bomb crater near the Brigade Headquarters position. Possibly shocked by the ferocity of the battle, the Americans and Australians did not pursue the Viet Cong regiment as it withdrew from the battlefield carrying hundreds more dead and wounded.27 The American defenders lost eleven killed and 72 wounded. Once again, they had won an impressive victory. The decisive factor had been timely artillery and tank firepower. A stray bullet, courtesy of either the Viet Cong attackers or the American defenders, grazed one Australian, who remained on duty.

On 8 March, a few weeks after decisively winning a national election that gave him a mandate to support the Americans in Vietnam, Prime Minister Harold Holt announced an increase in Australia’s contribution from 1700 personnel from all three services to a total strength of 6300 personnel.28 The core of this contribution would be an independent task force of 4500 personnel that would be responsible for the defence of Phuoc Tuy province, located on the coast 60 kilometres southeast of Saigon next to Bien Hoa province.29 Holt declared that the main body of this formation would depart on 6 June, giving the army less than three months to prepare a two-battalion task force with its headquarters and supporting logistic elements.30 This formation had to be raised within a numbers cap of 4500. Army Headquarters staff had offered this figure for use in Cabinet submissions without analysis of possible military roles and tasks in Vietnam.31 During the following busy three months, the army sowed the seeds for ‘consequential difficulties’ that were ‘to cause many problems when the task force deployed to Vietnam’.32 On 10 March 1966, 1 RAR flew by helicopter into an area 25 kilometres north of Bien Hoa on the southern banks of the Song Be and secured LZ Bugs Bunny. After the Americans pounded the opposite banks with artillery, mortar and helicopter gunship fire, the Australians crossed the river in American landing craft protected by thick fog. Viet Cong riflemen killed one Australian and an American as forward troops secured the far banks for the passage of the brigade’s airborne battalions into War Zone D.

For the next week, the Australians waged an intense patrol battle with reconnaissance elements of the Viet Cong 9th Division and local force guerillas around the brigade fire support base, the location of field guns and mortars and their ammunition, as well as supplies for patrolling troops. Australian ambushes successfully prevented the enemy gaining information on the layout of the base.

Lieutenant Colonel George Dexter, commanding 2/503rd Battalion, later contrasted the American and Australian operating methods:

When we [the paratroopers] found something, we shot at it. We did not wait and establish the patterns, look for opportunities after out-thinking the local Viet Cong commander. We were just not patient enough—there was too much to do in too little time. We did not use reconnaissance enough. Our ambushes were for security, not to kill. Australians were quiet hunters—patient, thorough, trying to out-think the Viet Cong. I would not have liked to operate at night and know there was a chance of ending up in an Aussie ambush.33

During this operation, the paratroopers captured and destroyed a major Viet Cong headquarters while the Australians foiled Viet Cong efforts to attack the fire support base. Williamson had blended American and Australian tactics. He established a fire support base deep in enemy territory knowing that the Australians would make it safe from attack. He then let his paratroopers loose to sweep forward, knowing that he had artillery, mortar and logistic support on hand.

Late in March General Westmoreland ordered the 1st Infantry Division (known as the ‘Big Red One’), reinforced by the 173rd Airborne Brigade and several South Vietnamese regiments, to search for and destroy the Viet Cong 5th Division in Phuoc Tuy province, where the 1st Australian Task Force would operate in two months’ time. The new commander of the 173rd, Brigadier General Paul Smith, directed the Australians to protect a sprawling fire support and logistic base that General Dupuy had established in the Courtenay plantation for the operation. During this operation, 1 RAR conducted the first of many Australian cordon and searches of the village of Binh Ba, detaining 33 local force guerillas. At the conclusion of the operation, the Australians had killed more Viet Cong protecting the divisional fire support base (fourteen killed, twelve wounded and 33 captured) than the sweeping brigades of the Big Red One.34 The Viet Cong 5th Division had not risked battle with the Americans as their comrades in 9th Division had done the month before in War Zone D.

The 1 RAR group returned to Australia in June 1966 after a demanding twelve months of almost continuous patrolling. Eighteen young Australians had lost their lives. The battalion group pioneered the development of new tactics and techniques for Vietnam that would become the standards for the following battalions of the regiment, as well as the supporting arms and services.35 This battalion also provided scores of combat-hardened officers, NCOs and soldiers who would teach newly raised Australian battalions how to fight in Vietnam. Those battalions would comprise a combination of newly trained national service riflemen and machine- gunners, and mostly newly promoted section commanders. Many 1 RAR veterans not only made sure that their protégés knew what was ahead of them, but also commanded and supported them during their tours of duty.

1 ATF Establishes its Presence

The arrival of 5 RAR and 6 RAR at Vung Tau, a port located on the south-east coast of Phuoc Tuy province, in May 1966 showed that the regiment was expanding and transforming from a conventionally trained, jungle-experienced force of volunteer professionals to an integrated force of regulars and conscripts, trained specifically for the operations in Vietnam. It also marked the first time that the Australian Army had had to establish forward operating bases overseas without substantial assistance from the British or American armies. Having relied on allies for just over 80 years, there were many problems with the occupation, establishment and operation of Australian bases.36 The choice of Nui Dat as a forward operating base and Vung Tau, 30 kilometres away on the coast, as a logistic support base, created a number of challenges and had some negative repercussions—especially on the infantry.

There was some debate at the time, and among historians later, about separating the forward operating and logistic support base.37 Nui Dat offered a Korean Warlike defensive position in the centre of the province astride a major route, away from population centres with their brothels and bars, as well as the prying eyes of enemy agents and saboteurs.38 The Australian task force commander, Brigadier David Jackson, would be able to launch operations from Nui Dat with a degree of surprise. However, Jackson displaced thousands of villagers to construct his base. Subsequently, he was obligated to defend it with 50 per cent of his infantry.39 Australian intelligence assessments stated that the key to success would be breaking the close relationship between the locals and the Viet Cong.40 The clearance of Vietnamese citizens, who were unlucky enough to be located on the approaches to the Nui Dat base, probably left many locals angry.41 Arguably, this outcome created an opportunity for the Viet Cong to mount attacks against the Australian base in secrecy.42 There were no Vietnamese to displace at Vung Tau—an inferior location in scrubby sand dunes—described by Lieutenant Colonel Rouse, commander of the logistics support group, as ‘disgusting’.43 On 5 June 1966, Brigadier Jackson flew into Nui Dat with his tactical headquarters and took command. The intelligence officer of 5 RAR, Captain Robert O’Neill, later wrote:

This force [1 ATF], as distinct from Australia’s earlier commitments, was supposed to contain sufficient elements to be essentially self-supporting, although certain foodstuffs and ammunition were supplied in bulk from the Americans . . . [However] shortages of essential items rapidly developed . . . Consequently, the forward troops lived in needlessly miserable conditions through their first wet season and some important aspects of security were not provided for.44

The security requirements for a two-battalion task force, located in enemy territory, reduced the Australian task force’s offensive capabilities significantly. Lex McAulay, a veteran of 1 RAR’s first tour, summarised the situation aptly:

Jackson could not get enough infantry for the many tasks necessary: to guard the developing base camp; to patrol close to and far from it; to carry out search operations for the enemy in nearby towns and villages; to be in readiness to move at once to engage located enemy; to be held ready to exploit any advantage from such an engagement; if needed, to guard the engineer and logistics activities; and to perform the thousand-and-one other tasks for which infantry are called.45

The first priority for the Australian task force was to ensure its own security.

Australian insistence on operating independently in Phuoc Tuy province created self-protection responsibilities. Jackson had to construct adequate fixed defences as well as put effective security arrangements in place to secure his supply route to Vung Tau. It would be a major military and political setback for the American and Australian build-up in Vietnam, if the Viet Cong attacked the Australian task force soon after arrival and caused significant casualties and damage. After arrival, Jackson and his battalion commanders, supported by artillery, armour, and engineer subunit commanders, conducted an aggressive, high-tempo patrolling program.

In early July, 5 RAR patrolled through the Nui Nghe area to the north and 6 RAR cleared the Long Phuoc area to the south of Nui Dat. By late July, the Viet Cong were hitting back. 6 RAR had its first taste of combat when A Company, D 445th Provincial Mobile Battalion engaged Bravo and Charlie Companies in a series of intense firefights to the east of the task force base. The Australians lost three killed and nineteen wounded, but were able to inflict thirteen killed and nineteen wounded before the Viet Cong dispersed.46

By the last week of July, 6 RAR was engaging well-trained and disciplined groups of Viet Cong in brief but fierce firefights in and around the home base of the 350-strong D 445th Battalion near the village of Long Tan, located six kilometres east of the Nui Dat base.47 However, the Americans and Australians did not expect a substantial attack on the base. The former inhabitants were gone, it was fortified and the perimeter patrolled regularly, under the cover of artillery and on-call helicopter gunships, jets and fighter-bombers.48 However, an unanswered question was where were the Viet Cong’s 1800-strong 274th and 1200-strong 275th Main Force Regiments of the Viet Cong 5th Division? Both were responsible for the defence of Phuoc Tuy province. Given the amount of disruption the Australians were causing, a response was a case of ‘when’, not ‘if ’.49 In early August, Brigadier Jackson directed 5 RAR to cordon and search the village of Binh Ba, located astride the northern approaches to the task force base. This operation made a deep impression on 5 RAR.50 Like their predecessors in 1 RAR in the La Nga Valley in November 1965, Lieutenant Colonel Warr and his men used stealthy movement and surprise. They sealed the village off before first light. South Vietnamese authorities told Warr later that they had identified and detained over 70 Viet Cong cadres, guerillas and sympathisers because of this operation. The South Vietnamese government now had 2000 people back under its control. The Australian operation had also re-established road access north to south through the province. For Warr and his staff this was an important precedent because the battalion had achieved these impressive results without one Australian casualty.51

By mid-August members of both 5 RAR and 6 RAR were tired after two months of patrolling by day and night, with no respite from base defence duties.52 A roster of recreation leave had begun, resulting in an absence of several platoons on leave that further stretched infantry resources and left gaps in capability. Coincidentally, the commander of the Viet Cong’s 5th Division ordered 275th Regiment to strike the Australian base.53 On 16 August he pre-positioned his regiment, just outside field artillery range, east of the Nui Dat base.54 Though Australian signals intelligence had pinpointed the location of the headquarters radio of the 275th correctly, Jackson’s staff did not react.55 The Viet Cong commander sent an emphatic and explosive calling card. In the early hours of 17 August, his gunners, mortar men and infantrymen bombarded the Nui Dat base for 22 minutes with 82 mm mortars, a Japanese Second World War-vintage howitzer and a number of recoilless rifles, wounding 24 Australians, and damaging seven vehicles and 21 tents.56

Jackson reacted to his opponent’s first move. On the morning of 18 August, he redeployed 5 RAR back to Nui Dat urgently from Binh Ba and directed 6 RAR to send out company patrols to search for the gunners and mortar crews who had perpetrated the attack. Delta Company, 6 RAR left after lunch to relieve another company. Late that afternoon at 4.00 pm, the advancing battalions of the 275th Regiment, reinforced by D 445th Battalion to an estimated strength of 2000 troops, ran into D Company in teeming monsoon rain. A ferocious battle began. Just over 100 diggers stood in the way of a Viet Cong regiment, intent on overrunning them so that they could attack the Australian base. The dispersal of the platoons made it difficult for the enemy to find D Company’s flanks and roll them up. This spreading may have also led to the Viet Cong commander assessing that he was facing a larger Australian force.57 It did not take Jackson or Townsend long to assess that the Viet Cong would overrun D Company if they did not organise reinforcement quickly. However, there was no quick reaction force prepared and rehearsed to deploy. There was just not enough infantry to have kept such a force in reserve and on stand-by. It took several hours for them to organise an ad hoc relief force of A Company, 6 RAR, mounted in armoured personnel carriers (APC).

By 6.45 pm, two and a half hours after the battle had been joined less than five kilometres east of the task force base, D Company had regrouped into a defensive circle with their wounded. The Viet Cong had them boxed in on three sides. If they were able to attack from several directions at once in the next fifteen minutes, under the cover of late afternoon gloom and sheets of rain, they would split defensive artillery fire. In so doing, they might get sufficient attackers through the ring of Australians to slaughter them.58 By this time, the rescue force had just arrived.

Vehicle commanders began firing 50 calibre heavy machine-guns at elements of D 445th Battalion located on the flank of 275th Regiment, while infantry in the back joined in with machine-guns and rifles.

After a number of impromptu and uncoordinated APC movements, Lieutenant Colonel Townsend arrived in an APC and took command. He directed Lieutenant Adrian Roberts, commander of the APC troop, to assault the flank of the main enemy force confronting D Company with infantry remaining in the back. Roberts did so, with infantrymen firing rapidly from open hatches into the Viet Cong ranks lining up to attack D Company.

The arrival of armoured vehicles broke the Viet Cong’s will to continue the battle.

Their commander ordered his troops to leave the area carrying most of their dead and wounded. After a difficult period handling the Australian dead and wounded in the dark, Townsend’s force moved by APC and on foot at 10.45 pm to a nearby landing zone—seven hours after some men had been seriously wounded. Leaving the dead, wounded, and possible survivors of D Company’s forward platoon on the battlefield that night was a bitter ending to what Jackson and Townsend initially interpreted as a military disaster: one platoon destroyed and—by Australian standards—heavy casualties sustained by the remainder of the company with nothing to show. At the Long Tan rubber plantation, the Australians replicated several of the battles fought by the 173rd Airborne Brigade in 1965 and in the first half of 1966 where artillery fire had saved paratroopers from massacre. The Americans had justified their sacrifices and claimed victory by reporting large body counts. It was now the Australians’ turn to do the same.

On the clear and bright morning of 19 August, Townsend returned to the battle site with a large force. The body count of 113 Viet Cong by 11.00 am confirmed that, in the official historian’s words, ‘D Company had achieved a stunning victory.’59 By 6.10 pm, the number of enemy dead counted reached 188 bodies. Drag marks, blood trails and the amount of abandoned weapons and equipment on the battlefield showed that there had been many more casualties. The Australians had lost seventeen killed and 21 wounded with two of the wounded having spent a terrifying night lying among the bodies of their mates and Viet Cong dead, watching the Viet Cong stretcher-bearers and scores of Vietnamese villagers drag away bodies and evacuate casualties.60

Following the battle of Long Tan, 6 RAR conducted Operation Smithfield in an attempt to follow up the withdrawing Viet Cong. Troops of the battalion move past Australian APCs as part of the operation (AWM photo no. CUN/66/692/VN).

The meeting engagement with D Company had not only postponed a Viet Cong attack on the Australian base indefinitely, but had effectively deprived the 275th regimental commander of the strength of two battalions.61 A combination of the battle discipline and bravery of the members of D Company, the cover provided by torrential rain and low ground, and the effect of hundreds of artillery and mortar rounds falling among the Viet Cong attackers delivered the victory. The battle of Long Tan was a further enhancement of the fighting tradition of the Australian army in general and Australian infantry, artillery and armour in particular as well as confirmation of the bravery of Australian air force and American army helicopter pilots. The battle also highlighted the professionalism and decisive role played by New Zealand gunners from 161st Field Battery and their forward observer attached to D Company, Captain Maurice ‘Morrie’ Stanley, in support of their ANZAC comrades. The Americans acknowledged this Australian feat of arms through the award of the United States Presidential Unit Citation.

Jackson was unable to mount an operation immediately after the battle to pursue the mauled 275th Regiment because of the vulnerability of the Nui Dat base to an attack from the 275th’s comrades, the 274th Regiment. However, seven days later the US II Field Force decided to launch a large-scale sweep of Phuoc Tuy province, called Operation Toledo, to find and fight the 274th and 275th Regiments. The Americans deployed two brigades of the 1st Division, the 173rd Airborne Brigade, a Marine battalion, several South Vietnamese battalions and 5 RAR. O’Neill wrote:

[T]he battalion had been keyed up to the possibility of a major encounter with the Viet Cong—a battle which would have had a decisive effect on the Viet Cong in Phuoc Tuy Province. Instead, all we found was dense jungle with no trace of any large Viet Cong force ever having been in the area.62

After September 1966, task force operations fell into three categories: conventional, pacification and security. Conventional operations involved patrolling and ambushing in remote areas of the province to search for and destroy main force Viet Cong units, their bases and supplies. Pacification operations involved patrolling and ambushing close to population centres to separate the Viet Cong local forces and cadres from the people and to disrupt the Viet Cong’s ability to move about and supply their forces. These operations were often characterised by cordon and searches of villages and the conduct of civic action programs.63 There was close cooperation with local South Vietnamese authorities, police and militia units. In effect, the Australians confined the inhabitants of villages within a circle of soldiers and armoured vehicles and protected South Vietnamese government officials, police and militia while they screened people and interrogated suspects. Security operations ensured that the Nui Dat base and the routes to and from it were safe and clear from enemy interference. These operations were constant, boring, manpower intensive and time consuming.

The constant feature of all of these types of operations was long patrols carrying heavy weights. The 6 RAR illustrated history observed:

Patrolling is the bread and butter of the infantryman. No one of 6 RAR can remember his tour in Vietnam without thinking of patrols . . . To protect the First Australian Task Force Base, complete security out to medium mortar range had to be assured. This could only be done by constant patrolling: infantrymen on the ground, walking in the pouring rain or through intense heat; struggling across swollen rivers and paddy fields or tearing their way through thorny bamboo or jungle. These were the men who kept the Viet Cong at arms length. It was a common sight for other members of the Task Force to see these patrols returning [from ambushes] first thing in the morning, unshaven, red-eyed and still wet either from rain or sweat, making their way towards their lines . . . It was a soul-destroying job.64

Jackson favoured conventional operations: short-duration search and destroy sweeps. He wanted to find and fight the D 445th Provincial Battalion and its local force sub-units. However, the Viet Cong were elusive and difficult to bring to battle and they reoccupied base areas soon after the Australians left.

[The pattern was] a multitude of contacts with small groups of Viet Cong, by all companies. The larger forces had withdrawn, the smaller caretaker members of the enemy using delaying tactics such as Claymore mines [an anti-personnel mine that blasted thousands of small metal fragments at troops] and booby traps, to slow down the battalion’s advance and cover their own withdrawal . . . Mines were a constant hazard.65

Jackson also employed cordon and search tactics. In October and November, 5 RAR and 6 RAR companies surrounded several villages. South Vietnamese authorities and police subsequently netted five Viet Cong, eleven suspects and a number of South Vietnamese Army deserters and draft evaders.

In December 1966, Lieutenant Colonel Warr and his staff reassessed their operational aim in order to come up with better tactics and techniques for operating successfully in Phuoc Tuy province.66 Warr considered that:

The most fundamental question seemed to be the determination of our aim. Was it to kill Viet Cong, to bring the main force to battle, to isolate the main force from the people, to assist in civic reconstruction, to restore Government control to the villages or to cut the Viet Cong supply lines? . . . Quite clearly, the fundamental element in the Viet Cong strategy was the people. They were fighting the war for the control of the people . . . In eight conventional operations in which we were fighting Viet Cong main and mobile force troops, we [5 RAR] suffered six killed and 31 wounded while the Viet Cong lost 33 killed and two captured. In five cordon and search operations, we suffered one death and none wounded for a loss to the Viet Cong of 16 killed, 47 captured and 112 suspects taken.67

Warr wanted to move away from conventional operations and focus on population control and disrupting supply lines and Viet Cong freedom to move among the population.68 He assessed that 1 ATF did not have the strength to destroy the Viet Cong 274th and 275th Main Force Regiments in combat. He favoured cordon and search operations to eliminate Viet Cong cadres and disrupt the outflow of rice from the villages to the enemy.69 In December 1966, the situation in Binh Ba typified Warr’s concerns:

[A]t night the area [Binh Ba] is penetrated almost at will by small groups of village and at times district level VC guerillas. Such bands have been involved in clashes with RF [South Vietnamese militia] patrols but generally, such incursions are aimed at harassment of the civilian population, tax gathering, and the dissemination of propaganda.70

In early January 1967, Warr discussed his ideas with Brigadier Stuart Graham, who had succeeded Brigadier David Jackson as Commander 1 ATF, and received approval for his concept of operations. On 9 January 1967, 5 RAR returned to Binh Ba. Robert O’Neill, who served with 5 RAR, later observed that:

[A] new cadre-in-embryo composed mostly of persons under twenty was dissolved and our determination to keep the Viet Cong out of Binh Ba was demonstrated . . . they [the Viet Cong] had not come back into the village to make another attempt to establish a cadres before we [5 RAR] finished our period of duty in Vietnam [June 1967].71

McNeill and Ekins opined:

Operation Caloundra ended in mid-afternoon and was considered a complete success. Not a shot was fired, and of some 1500 villagers screened, 591 were interrogated. Nine confirm[ed] members of the Viet Cong identified and taken prisoner. They were mostly people under 20 years old. A further five draft dodgers were detained.72

Balancing Tactics and Techniques

In February 1967, Brigadier Graham decided to focus task force operations on the Dat Do area and the south-east of the province.73 He initiated a comprehensive program of conventional and pacification operations. Apparently ascertaining the mood and preferences of each of his battalions, he directed 5 RAR to concentrate on cordon and search operations and civic action, and employed 6 RAR more as a search and destroy battalion.

For the first week of February 1967, 6 RAR ambushed Route 23 between the town of Dat Do and the Suoi Tre River. This operation was a pre-emptive deployment to forestall Viet Cong attacks in the area to mark the Tet (New Year) holiday period. Though results were inconclusive, D Company, 6 RAR suffered further casualties when a misplaced artillery mission from the New Zealand 161 Field Battery killed four and wounded thirteen members. Among the dead was the company sergeant major, Jack Kirby, who had received the Distinguished Conduct Medal for bravery at Long Tan in August.74 5 RAR was having some success with cordon and search operations. On 13–14 February, the battalion helped South Vietnamese authorities apprehend fourteen suspects, five sympathisers, two South Vietnamese Army deserters and a draft dodger during a cordon and search of the village of An Nhut, just west of Dat Do. However, the deaths of C Company’s commander, his second-in-command, and a New Zealand artillery forward observer from a mine marred this result. After this operation, O’Neill commented that 5 RAR had captured 40 Viet Cong in six days for the loss of these three lives.75

In contrast to 5 RAR’s operations against Viet Cong cadres in villages, Graham sent 6 RAR after D 445th Battalion. Townsend mounted Operation Bribie in mid-February as a response to D 445th Battalion elements attacking a South Vietnamese regional force compound in Lang Phuoc Hai area, near the village of Hoi My.76 He deployed C Company mounted in APCs to the area and assembled the remainder of the battalion for a move by helicopter to engage the Viet Cong attackers and block their escape routes. It turned out that the Australians became the prey. Helicopters dropped A Company into an unsecured landing zone adjacent to dense jungle where a large group of Viet Cong, reinforced with North Vietnamese regulars, was resting in well-prepared, dug-in defensive positions. They opened fire with machine-guns and rifles as an Australian platoon approached them. A third of the platoon fell dead or wounded in the initial volley and following firefight.

While the company commander, Major Owen O’Brien, withdrew his platoons under heavy fire from what he described as an enemy camp, Townsend decided on a battalion attack plan. Employing the agility of helicopters, good communications, armoured mobility and artillery support, he ordered B Company to land on the flank of the Viet Cong position and prepare to assault it. He directed D Company to occupy a blocking position, and C Company, in the APCs, to move into another blocking position. B Company attacked the Viet Cong company, while A Company advanced and engaged the enemy again in order to provide fire support from a flank and to split enemy fire.

A five-hour-long battle at close range ensued until night fell. The Viet Cong dispersed, once again dragging away many dead and evacuating their wounded. During the battle, Australian platoons had assaulted enemy positions, taking and inflicting heavy casualties using frontal tactics more typical of the First World War than patrolling operations in Vietnam. Armoured personnel carriers were also involved and took both vehicle and personnel casualties.

This battle exemplified the difficulties the Australians had in destroying Viet Cong regular units. Despite Townsend’s pre-positioning of cut-off forces, the Viet Cong force withdrew safely carrying casualties. They had resisted Australian assaults and withstood the weight of artillery, mortar and aerial bombardment. 6 RAR lost the operational strength of a platoon: eight killed and 27 wounded. The Viet Cong probably lost the operational strength of a company.77 The question was whether this form of attrition would free the inhabitants of Phuoc Tuy province from Viet Cong control and allow the South Vietnamese government to govern. Brigadier Graham opined later that Operation Bribie was a victory. D 445th Battalion was not able to mount a full battalion operation for the remainder of 1967; the morale of local South Vietnamese regional force and popular force soldiers received a boost; for the first time, local people in this area realised that membership of D 445th Battalion was hazardous and more North Vietnamese regulars had to fill gaps in the ranks.78 The official Australian historians assessed that Bribie ‘was no Australian victory—at least to the soldiers involved’.79

As 6 RAR returned to Nui Dat on 18 February from another traumatic battle experience like the battle of Long Tan, Brigadier Graham sent 5 RAR to the Long Hai hills ‘to clear a substantial part of the hills complex’ before a cordon and search of a nearby village of Phuoc Hai.80 This operation began a long and tragic association between members of the regiment and the Long Hai hills.81 It began with a massive B–52 bomber strike. The Australians arrived by APCs and patrolled along the road in search of their opponents. Viet Cong units had already left the area, warned by preliminary APC reconnaissance activity the day before. They countered the Australian advance with an improvised explosive device and anti-personnel mines.82 On 21 February a Viet Cong operator detonated a 500-pound American bomb under an APC with a section from B Company aboard—killing three and injuring nine more. When nearby soldiers rushed to help their fallen comrades, someone detonated an American ‘jumping jack’ anti-personnel mine that was designed to maim and cut off lower limbs, rather than kill. However, this mine explosion killed two more soldiers and wounded nineteen more. The Australian death toll now stood at seven killed with 22 men seriously wounded and needing immediate medical evacuation. There were many acts of bravery in the coming hours as every one of these men was evacuated amidst the ever-present danger of further mine detonations.

Prompted by intelligence reports that regiments of the Viet Cong 5th Division were on the move to attack the task force base at Nui Dat, Brigadier Graham hastily redeployed 5 RAR back to Nui Dat to join 6 RAR manning the base’s defences. For many members of 5 RAR, this hasty move back to Nui Dat smelt of defeat, despite their commanding officer assuring them that this was not so.83 After a few days, Graham assessed that the Viet Cong had abandoned their attack plans. Several officers within the task force, including Graham, were now convinced that the task force needed a third infantry battalion, a squadron of Centurion tanks and more support troops to increase capability. There was just too much to do with only two light infantry battalions and an APC squadron. Though it was not Australian doctrine to support infantry with tanks for counterinsurgency warfare, the experiences of the Battle of Long Tan, and on Operation Bribie, were exhibits A and B for change. In June 1967, Major General Vincent sent a detailed submission to Lieutenant General Sir John Wilton, Chairman, Chiefs of Staff Committee, requesting a reinforced independent tank squadron of four troops of Centurion tanks and asking for them to be operational in two months’ time.84

Final 5 RAR and 6 RAR Operations

During the final months of their tours of duty, Brigadier Graham employed 5 RAR and 6 RAR as he had done from the beginning of his period of command. He also decided to enhance the security of the task force base by constructing a forward base at a place called ‘the Horseshoe’ and interfere with enemy movement by laying an eleven-kilometre barrier minefield enclosed by a thick barbed-wire fence from the Horseshoe to the sea. When completed, this minefield contained a total of 22,592 M16 anti-personnel mines, 12,700 of which were fitted with anti-lifting devices. Unfortunately, this minefield would not meet Brigadier Graham’s expectations and would become an Australian military tragedy.85

In March 1967, the Australians, accompanied by a number of American infantry and cavalry units, went out after the Viet Cong 275th Regiment again. Operation Portsea was a response to this regiment’s attack on the small popular force outpost of Lo Gom, a few hundred metres north of the village of Phuoc Hai on the coast. Graham’s Task Force Headquarters coordinated a large-scale sweep by a brigade from the US 9th Infantry Division, the US 11th Armoured Cavalry Regiment and 6 RAR. The 275th Regiment evaded sweeping American and Australian forces and pre-positioned blocking forces. This indecisive search and destroy operation marked the end of 6 RAR’s tour of duty. The battalion’s history concluded with the ‘butcher’s bill’:

For 6 RAR, it had been a busy year. Thirty-six members of the battalion had died during that time, and its members had won 13 decorations and awards. It had five major clashes with the Viet Cong, and had fought some decisive battles. D Company had won the battle of Long Tan, and A and B Companies had been involved in grim struggles with main force units during Operation ‘BRIBIE’. All told, the battalion had accounted for 302 enemy dead in 21 operations.86

5 RAR ceased operations on 26 April and set sail for Australia four days later. The battalion’s self-assessment also contained a ‘butcher’s bill’, but included additional measures of success as well.

We [5 RAR] killed seventy Viet Cong for a loss of twenty-three of our men. If one views the war in terms of dead bodies counted, then these results do not justify the employment of 800 Australians at war for 12 months and an uninformed observer might jump to the conclusion that the war was at a stalemate. On the other hand, if one accepts that the goal of the war is the support of the people, these body count comparisons are the wrong statistics to consider. The important figures in this war are the numbers of people who support the Government, the degree of Government control and the speed with which the support of more South Vietnamese is won.87

5 RAR’s chronicler had correctly identified the political objectives of the Vietnam War. However, South Vietnamese authorities, military forces and police were unable to deliver security, law and order, or effective governance. The Viet Cong were still able to infiltrate towns, villages and hamlets, despite the presence of seventeen regional force companies and 47 popular force platoons in Phuoc Tuy province.

There is also evidence that local South Vietnamese authorities and security forces may have aided or at least ignored this infiltration.88 On 12 May, 5 RAR arrived in Sydney, and marched through the city to what the official historians, Ian McNeill and Ashley Ekins, described as ‘a tumultuous welcome by a huge crowd, reportedly numbering 400,000 people, who cheered the soldiers and showered them with confetti and streamers’.89 The citizens of Queensland turned out for 6 RAR in Brisbane on 14 June. A crowd of 100,000 people gave the battalion ‘a ticker-tape welcome’ as they marched through the city.90

Operations of 2 RAR and 7 RAR in 1967

It was now the turn of the newly raised 7 RAR, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Eric Smith, and reorganised 2 RAR, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Noel ‘Chick’ Charlesworth, to maintain a deterrent presence in Phuoc Tuy province and continue the work of the Australian infantry with their special force colleagues.91 By this time, there were even more national servicemen among the ranks. Unlike other armies containing conscripts, an extremely selective process resulted in a ‘high-calibre of national service soldiers’.92 Less than 2 per cent of those men who registered for national service, and less than one-quarter of those actually called up, served in Vietnam.93 Anzac Day 1967 marked the second occasion in the history of the regiment that three of its battalions were on parade in a theatre of operations. In April 1953, 2 RAR had paraded with 1 RAR and 3 RAR in South Korea. On 25 April 1967, three new battalions of the regiment, 5 RAR, 6 RAR and 7 RAR, paraded at Nui Dat. It was a visible reminder of the continuity and expansion of the regiment, as well as the importance of Australia’s infantrymen in representing Australia’s national interests on overseas military campaigns.

An Anzac theme continued after 2 RAR’s arrival in Vietnam in May. The New Zealand government had directed 1st Battalion, Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment (1 RNZIR) to raise a composite infantry company to serve in Vietnam with the Australians. Victor (V) Company arrived to join 2 RAR as a fifth rifle company. This was the first time that there was an official integration of Australian and New Zealand infantry soldiers into an Anzac battalion, sharing the risks of combat, side by side under one name with one purpose, and commanded by an Australian.94 In June 1967, like their predecessors, the first operations for the newly arrived battalions focused on maintaining the security of the task force base. After acclimatising to field conditions in Vietnam and conducting local search and destroy sweeps, they were ready to conduct their first large-scale operations with American units in the May Tao mountain area, the home base of the Viet Cong 5th Division. Once again, the mission was to bring the 275th Viet Cong Regiment to battle.

While 2 RAR and 7 RAR occupied blocking positions north-east of the village of Xuyen Moc, American and South Vietnamese battalions attempted to drive Viet Cong forces towards them. Lieutenant Colonel Smith commented to journalists at the time: ‘We were in a blocking position, and the enemy just did not run our way—much to the disgust of our boys.’95 Conventional tactics of ‘hammer and anvil’ had not worked once again.96 After this operation, Brigadier Graham allocated Charlesworth the area east of Route 15 and directed Smith to operate west of Route 15.97 During August 1967, Smith and Charlesworth conducted independent search and destroy operations.

2 RAR began its account with Operation Cairns in the area of the ‘Long Green’, east of the town of Dat Do.98 Viet Cong main force units used the concealed jungle tracks and trails of the area to infiltrate into southern Phuoc Tuy province from their bases in the north. The area contained supply dumps of equipment, arms and food as well as camps and staging areas. Of equal importance was its proximity to a large population and its function in the local economy as a rice, fish, salt and fruit producing centre.

On 25 July, 2 RAR entered the area silently, on foot and by night, surprising several small Viet Cong sentry groups in the morning. Once the enemy knew the Australians were in the vicinity, they disappeared into the tunnel systems and hides, leaving behind booby-trapped mines. These devices killed two Australians and wounded seven others. The Australians found and neutralised 22 mines that morning. Some of them came from the barrier minefield constructed by fellow Australians three months before.99 The net results of their operations were the deaths of a small number of local men and youths serving with the Viet Cong and the disruption of enemy operations in the area for a week.

Members of A Company, 7 RAR cross a paddyfield south-east of the 1 ATF base at Nui Dat in September 1967. The patrol, along the coastal strip of Phuoc Tuy province, was part of a move of the battalion to prevent Viet Cong reinforcements, supplies and equipment entering the province by sea (AWM photo no. CAM/67/804/VN).

On 4 August 1967, 7 RAR moved south-west of Nui Dat to gather intelligence on the enemy’s activities and habits’.100 Companies entered their areas of operation on foot, in silence and carrying five days’ rations. Their stealthy arrival caught several Viet Cong sentry groups by surprise. Major Ewart ‘Jake’ O’Donnell’s A Company patrolled up to the forward company and reconnaissance platoon of 3rd Battalion, 274th Viet Cong Regiment, accompanied by a group of local force guides who happened to be moving through the area.101 The Battle of Suoi Chau Pha ensued.

The initial firefight began with the Australians taking the initiative. Second Lieutenant Graham ‘Pud’ Ross’s platoon made a quick attack on a squad of Viet Cong who had gone to ground after Ross’s men had shot at them. The attacking Australians hit a wall of fire from a Viet Cong platoon that had gone to ground after hearing the firefight ahead of them.

Major O’Donnell went forward to find the flank of the platoon that had halted Ross’s platoon assault. After indicating an axis of attack to Second Lieutenant Rod Smith, he ordered a right flanking platoon attack into the enemy platoon. As Smith’s assault line drew level with Ross’s platoon, they found themselves facing a Viet Cong platoon doing the same as they were trying to do. O’Donnell’s opposing company commander had ordered a flanking attack on Ross’s platoon that now coincided with Smith’s assault on the flank of the Viet Cong platoon. Two Viet Cong platoons and two Australian platoons now stood at ‘toe to toe’ in a shoot-out at a range of 20 to 30 metres.102 ‘Our boys cried out in pain when they were hit’, wrote Captain ‘Nobby’ Clark, the company’s artillery forward observer, ‘but the enemy screamed. You could hear them above the sound of battle—piercing and soul-destroying.’103 Like the Battle of Long Tan, a monsoonal downpour as well as a rain of artillery shells determined the course of the battle in favour of the Australians. Clark observed that ‘The noise [of enemy small arms fire] was appalling, the visibility down to a few metres and all I could think of was, “Jesus, make it stop.”’104 After hearing shouted reports that scores of Viet Cong were massing for an attack, Clark ordered an artillery mission that resulted in rounds falling among the Viet Cong and members of Smith’s platoon. Fortunately, the point of impact resulted in the shrapnel scything forward through the enemy assault troops who were standing up and running. One round hit a tree, slightly wounding a few Australians, who were lying on the ground firing their weapons. This artillery strike convinced the Viet Cong battalion commander to withdraw. He had taken too many casualties from Australian small arms fire, grenades and artillery shells that not only fell on his forward attacking troops, but also on those gathered behind them to join in the attack.105 The Viet Cong had killed six Australians and wounded another nineteen. For their part, the Australians recovered several Viet Cong bodies and estimated that artillery and mortar fire as well as air strikes had caused a further 200 casualties to their opponents.106

Resettlement and Reorganisation

From August until September 1967, the Australian task force conducted an operation that was to prove to be ‘one of the most ambitious the Australian force conducted during its entire time in Vietnam’. The aim was to relocate about a thousand villagers from an area known as ‘Slope 30’ to a purpose-built hamlet. This operation and its consequences would become ‘an enduring source of controversy [as it] served to impose greater hardships and insecurity on the villagers while also alienating them’.107 The Australian infantry found themselves in the unaccustomed role of conducting a census of the families living in and around the village of Xa Bang north of Nui Dat on Route 2 and then providing protection while South Vietnamese authorities moved them in trucks to a newly constructed hamlet, Ap Soui Nghe, just north on the Nui Dat base. The objective was to resettle just over a thousand peasants in order to isolate them from Viet Cong influence and break up a supply system that the Viet Cong had set up in the Xa Bang area. Both battalions and the full resources of the remainder of the task force, coordinated by the civil affairs unit, resettled these villagers. However, the new hamlet was a miserable ‘soulless’ place that became a haven for Viet Cong.108

In September 1967, there was a significant turnover of national servicemen in 2 RAR and 7 RAR, causing massive disruption to established, cohesive fighting teams in platoons and sections. The departure of many fine young NCOs was a blow to morale and operational effectiveness. This turnover was to occur again in March 1968 as national servicemen completed their two-year obligation. A total of 1460 personnel served in 7 RAR during the battalion’s twelve months in Vietnam.109 Operations for the remainder of 1967 were similar to those the Americans and Australians had conducted over the previous two years. 2 RAR and 7 RAR deployed on several search and destroy operations aimed at disrupting Viet Cong activities east and west of Route 15. These operations also included searching villages in order to isolate the population from the Viet Cong during national elections.

The higher levels of American command persisted with operations intended to bring the main force Viet Cong units to battle. On 26 October, 7 RAR joined the US 9th Division and the 18th ARVN Division on Operation Santa Fe, a major thrust into the May Tao Secret Zone to find and fight elements of the Viet Cong 5th Division.110 American, Australian and South Vietnamese units unearthed and destroyed many tonnes of foodstuffs and military supplies, and over a thousand bunkers and military structures.111 After Operation Santa Fe, 2 RAR and 7 RAR conducted several search and destroy operations in areas near Nui Dat until Christmas 1967. These operations now included activities that 5 RAR had favoured the year before. The Australians cordoned off and searched villages for foodstuffs and military supplies. 2 RAR supported large-scale screening operations by South Vietnamese authorities to identify Viet Cong political cadres and sympathisers. There were no major battles during this period and only sporadic contact with armed groups.

For eighteen months, the Australian task force had concentrated on reducing the Viet Cong’s influence in Phuoc Tuy province through conventional, pacification and security operations. From July until December 1967, 2 RAR and 7 RAR followed precedents set by their predecessors in 5 RAR and 6 RAR. The largely unheralded Battle of Suoi Chau Pha repeated the conditions of the Battle at Long Tan on a smaller scale, but with similar displays of courage and battle discipline.

Brigadier Graham reportedly stated to his successor, Brigadier Ron ‘Wilbur’ Hughes, that the Viet Cong were virtually finished in the province.112 This was an optimistic assessment. The 275th and 274th Regiments of the Viet Cong’s 5th Division were still as elusive as ever and North Vietnamese regulars were reinforcing them steadily. The D 445th Provincial Battalion still thumbed its nose at the Australians. In addition, the Viet Cong’s political and administrative network still had control over much of the population. They continued to murder South Vietnamese government officials and local leaders, as well as members of their families. Ominously, the Viet Cong had already begun to lift mines from the Australian barrier minefield for use against American and Australian forces.

In December 1967, Lieutenant Colonel Jim Shelton, a Korean War veteran who had been a company commander during the battle of Maryang San, arrived with ‘Old Faithful’—3 RAR—to bring the task force up to three infantry battalions. A squadron of Centurion tanks was also on the way. This would prove to be a timely reinforcement, as the Second Indo-China War was about to enter a new phase. Since the American and allied escalation in 1965, the communists had worked out how to offset American superiority in mobility and firepower. According to McNeill and Ekins, there were a number of factors that diminished allied technological superiority that would now make the war a test of wills—a war of bloody attrition.113 The North Vietnamese and their Viet Cong surrogates were building up for an offensive during the Vietnamese New Year, called Tet, in January–February 1968. The Australian task force was about to return 1 RAR’s operating areas of 1965–66 to defend the approaches to Saigon. Well-trained and fully equipped main force Viet Cong formations awaited them, supported by North Vietnamese Regular Army units, who were about to join the Viet Cong throughout South Vietnam in a bid to drive the population into armed uprising.