11 Pacification in Phuoc Tuy Vietnam, 1969–72

Jerry Taylor

At 7.00 pm on 11 August 1970, 8 Platoon, C Company, 8 RAR left Nui Dat by vehicle and moved south along Route 2 to Baria. After dusk they then went back the way they had come. As they neared the village of Hoa Long the platoon dropped from the moving vehicles and disappeared into the dark. By 7.45 pm they were in an ambush position barely 1000 metres south-west of the village. As they waited in fire positions behind the paddy bunds, moonlight gave them visibility of about 200 metres with the naked eye, and up to 500 with Starlight scopes. At 9.00 pm the rear protection group reported 50 to 60 enemy soldiers moving east towards Hoa Long. They were crouched and alert, moving fast in open file along parallel bunds about 100 metres away.

The dilemma that faced Sergeant Chad Sherrin, the platoon commander, was whether to open fire now at this range and risk losing the bulk of the enemy as they fled; to let them go and miss any chance at all of inflicting at least some casualties on them; or to wait, in the hope that they might re-emerge from the village along a similar route later in the night. Sherrin decided to wait, and moreover to relocate his men closer to the route the enemy had used into the village. By 11.00 pm the platoon was redeployed into its new positions, in four groups of five men with a machine-gun.

At 3.15 am the watching infantrymen saw the dark figures leaving the village in two groups of about 25, approximately 30 metres apart. They were bunched up, heavily laden and moving without caution. When the enemy was ten metres away the second ambush group fired its claymore mines and those left standing came under fierce crossfire from the other groups. A second enemy party was also engaged and when all movement had ceased 8 Platoon moved forward under artillery and mortar illumination to clear the killing grounds.

Nineteen enemy bodies were recovered, together with a large quantity of weapons, supplies and food. Subsequent searches in and around Hoa Long by national police and regional force units resulted in more enemy soldiers and supporters being captured and detained. Such attacks weighed heavily on the enemy and it was later found that they suffered from ‘a marked lowering of morale, even to the stage where enemy soldiers malingered to avoid participation in resupply missions’.1

The Commander, Australian Force Vietnam, Major General C.A.E Fraser, congratulates Sergeant Chad Sherrin on his successful conduct of an ambush in August 1970 in which nineteen enemy were killed by 8 Platoon, 8 RAR. On the right is the commanding officer of 8 RAR, Lieutenant Colonel K.J. O’Neill. Sherrin was awarded the Military Medal for his command during the ambush (AWM photo no. War/70/670/VN).

This ambush, for which Sergeant Sherrin received the Military Medal, was a successful example of the types of operations that the task force had been undertaking in Phuoc Tuy province since the start of the Pacification Program that had started in May 1969. The program sought to increase and improve the government’s control over the rural population of South Vietnam, and included the goals of maintaining rural security, reasserting local political control, and fostering local economic and social activity, including the development of local infrastructure.2

Pacification was not a new concept. In 1955 the Diem regime introduced a series of programs to improve rural security and in 1966–67 the government restated the need for pacification with the Revolutionary Development Program. The program stressed the need for community development projects including land reform and agriculture, public works, health, education, and most important of all, the security of the people against enemy exploitation and attack. Despite the initial psychological effects of the Tet offensive, especially in the rural areas, the pacification effort was expanded. This now also included increased recruiting and better training for the regional forces (RF) and popular forces (PF) whose inadequate leadership, resources and training had rendered them until now largely ineffective.

With President Nixon’s emphasis on ‘Vietnamisation’ and the end of the major Tet battles of 1968, the task force’s focus shifted back to Phuoc Tuy and its pacification. Consequently, on 16 April 1969, the Commander 1 ATF, Brigadier Sandy Pearson, received a new directive that changed his operational priorities. The first was to be pacification; the second was to improve the quality and effectiveness of South Vietnamese forces in the province; and the third was to continue military operations within Phuoc Tuy.3 So, between May and September 1969, task force operations were characterised by a sustained effort to seal off and contain the enemy from the population centres that were traditional sources of food, money, materials and recruitment. The aim was to make movement for the enemy between their bases and the villages as difficult and dangerous as possible. As an adjunct to this, the local RF and PF units would be made more efficient and effective in carrying out their roles in preparation for a more active part in the war.

With this in mind, on 6 May 9 RAR, less C Company, deployed from Nui Dat with the mission to assist with population security in the Long Dien and Dat Do districts, and other districts from time to time. C Company remained under command but had the task of training the 2/48th ARVN Battalion; except for one instance, C Company did not take part in the population security mission. The battalion set up a fire support base on the Horseshoe to cover the deployment and then moved to FSB Thrust in AO Aldgate. The area of operations covered Long Dien, Dat Do and the villages that spread southwards to Lang Phuoc Hai on the sea. The first stage of the operation was mainly to conduct ambush patrols on likely enemy routes of movement by day and night, particularly from the Long Hai hills, which were a well-established enemy haven for replenishment and training.

Most of the pacification operations in 1969 and 1970 centred on the area between Dat Do and the coast, and this area was dominated by the fire support base at the Horseshoe, the rim of an extinct volcano just north of the village of Dat Do, a known hotbed of VC activity. The photograph, taken looking south-south-west, shows the Horseshoe in the foreground, the large area of trees in the centre is Dat Do, and across the paddy fields in the distance are the Long Hai hills. Patrolling out from the Horseshoe the Australian battalions tried to intercept the movement of VC between the Long Hais, the surrounding villages and the jungle to the north and east of the area (photo: A. Mattay).

Working with 9 RAR was a troop of tanks of B Squadron, 1st Armoured Regiment; a section of A Squadron, 3rd Cavalry Regiment; three combat engineer teams; and a land clearing team from 1st Field Squadron. A company of the battalion together with the section of APCs was always deployed as part of the land clearing team and assisted in protection and movement. The tanks provided additional protection for the land clearing team when its operations were threatened from the high ground of the Long Hai hills. As the operation developed it was necessary to allot one company to work with and train the RF/PF posts in Dat Do. This then left only one company for ambush tasks.

On 15 May sector authorities advised that two enemy companies had entered Dat Do; 9 RAR deployed in block and ambush positions around the village to assist the 1 ATF ready reaction force (W Company, 4 RAR/NZ), which came under command. C Company, 9 RAR participated in the block. Nothing eventuated during the night of 15 May and the following day B Company, 9 RAR assaulted selected areas in the south-west of the village to drive the enemy into the block, but there was no result. On 17 May two ARVN battalions swept through the town also without result.

Two types of patrolling were conducted in Dat Do: both ambush and ‘soft shoe’ patrols were used in the built-up areas. No contact was made with the latter method but perhaps the VC kept clear of the village at night because of the presence of these patrols. Nevertheless throughout the operation 9 RAR had frequent contact with enemy moving along tracks to and from the population centres. Training the RF/PF was very successful and land clearing greatly hindered enemy movement by night and day. As 9 RAR was the first of the Australian battalions to engage in a new series of pacification operations on the scale required by 1 ATF, much time was spent establishing contact with the ARVN elements, the district chief and senior officials of the population who were willing to help. The results of the operation could not be measured after only four to five weeks but it seemed that there was a hopeful change in the attitude of the local officials and a slight improvement in acceptance by some of the people.

Pacification operations continued in Operation Esso in June–July 1969, when the companies of 5 RAR were required to provide small training teams to RF/PF posts throughout Dat Do district. Their task was to help train these local forces in individual skills and sub-unit drills, and by their presence to bolster morale and encourage a more professional and aggressive attitude of local forces towards their role. At the same time government agencies were pressed to provide greater supervision over the rice control programs. Police, RF and PF, and agency officials were persuaded to man checkpoints on the roads and tracks leading in and out of Dat Do, Baria and the other principal villages. These methods, combined with the relentless ambushing carried out by the 5th, 6th and 9th Battalions, were successful, and over the ensuing months captured documents revealed that enemy units were finding it increasingly difficult to operate and to feed themselves. Nevertheless, the operations were not without cost to the Australians. Casualties from mines were considerable, and were causing concern in Canberra.4 This growing threat to the task force came from mines lifted from the barrier minefield laid in 1967 by 1 ATF, and re-laid by the enemy in areas where the most damage could be done to Australian troops.

But it was not solely ambushing operations that occupied the battalions. Enemy units in their bases throughout the province still had to be pursued and brought to battle so that they could not develop their own operations against the task force, South Vietnamese forces, or the civilian population. Accordingly, on 29 July 1969, 5 RAR began Operation Camden, the main aim of which was to locate and destroy enemy units operating in the Hat Dich Secret Zone. It will be recalled that this was one of the main enemy operational and logistic base areas situated in the north-west of the province. The principal targets of 5 RAR were 274th VC Regiment, known to be about 700 strong, and the Headquarters of Sub-Region 4, which with its units numbered about 1100.

Lieutenant Colonel Colin Kahn’s plan was that one company of 5 RAR would remain in a night defensive position to provide security for the land clearing teams and to patrol by day and night. A second company was ordered to locate and destroy any enemy found in the areas that were to be land cleared in future. A third company was to conduct reconnaissance in force in AO Mindy (within the Hat Dich Zone), while the fourth company was detached to train members of 2/52nd Regiment, 18th ARVN Division at the Horseshoe. The battalion deployed on 29 July, and contact with the enemy came quickly. On the afternoon of 31 July, 7 Platoon, C Company fought a spirited bunker battle; 12 Platoon, D Company sprang a well-planned ambush on 6 August; and a composite force consisting of 3 Platoon, A Company and the Tracker Platoon, commanded by Captain Bill Grassick, fought another bunker battle with the 1/274th VC Regiment on the 8th.

3 Platoon, accompanied this time by the pioneer platoon, was again in the thick of it on 21 August, and when Grassick was severely wounded in the leg Lieutenant John James of 3 Platoon took over. Now it was the 3/274th Regiment, and only the determination and courage of the composite company, together with the use of sustained artillery fire, helicopter gunships, and fighter ground attack aircraft, eventually persuaded the enemy to withdraw.

During the course of the operation 5 RAR fought 40 separate actions. In addition, the land clearing teams cleared 3354 acres of jungle, destroyed 1029 bunkers, 379 weapon pits, 900 metres of tunnels and 600 metres of trench. Most importantly, enemy routes in and out of the area, until now concealed, were exposed to observation, and their use, though not terminated altogether, was made particularly hazardous.

Nevertheless, the principal lesson of the operation to 5 RAR and the rest of the task force was that the enemy, in this part of Phuoc Tuy at least, was far from beaten. The battalion found that:

Rather than breaking contact and withdrawing, the enemy stayed and fought in his prepared positions and defied the immense support of air and artillery to dislodge him. He then withdrew under cover of night . . . [and] he tenaciously clung to the Diggers as they pulled back to evacuate casualties and take resupply of ammunition. This tactic was well executed and consequently . . . [the enemy] avoided most of the artillery and air ordnance.5

While 5 RAR was engaged in operations in the Hat Dich, 6 RAR/NZ Battalion (which had arrived in Vietnam in May to relieve Lee Greville’s 4 RAR) was ordered to continue the work of pacification begun by the 5th and 9th in the enemy resupply areas around Dat Do and the Long Hai peninsula. Operation Mundingburra, beginning on 14 July, was to deny enemy access to these areas by deploying a screen of rifle companies well out from the population centres; to isolate local guerilla units from the population by deploying inside the villages; and having gained increased security within them, to assist local and district forces to increase their operations against enemy units and infrastructure. The overall objective of Mundingburra was to increase the confidence of the population towards local government. This would be a particularly exacting operation for the battalion and its commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel David Butler.

Dat Do had always been an important link in the enemy’s supply and tax collection chain. Control of supplies out of the village and its surrounding hamlets was a constantly difficult task, despite curfews, identity checks, and civilian and food controls. The population of the area was about 24,000, and to control this the RF and PF were able to muster only sixteen officers and 626 other ranks.

For the operation, W Company (Major L.G. Williams) was to operate in and around Dat Do to assist the civilian administration and police; and members of the Anti-tank Platoon were positioned in the RF posts at Long Thanh and Tam Phuoc to commence their training programs.

While these tasks continued inside the villages, 6 RAR was also busy in the surrounding areas. A Company ambushed routes and then began a reconnaissance-in-force to block major movements in and out of the villages. At the same time V and D Companies (Majors L.J. Lynch and I.T. Stewart) were ambushing, patrolling and calling down fire missions onto observed enemy movement from the Long Hais to the villages along Routes 23 and 44. D Company had also been allotted an additional task: to protect the land clearing teams who were removing the scrub which for so long had provided cover for enemy movement into the population centres. Meanwhile B Company was established in a small fire support base on Nui Dat near Xuyen Moc, and was patrolling vigorously to locate the Xuyen Moc Guerilla Unit (C 23) and the Xuyen Moc (VC) District Party Chapter, the destruction of which would break the logistic line between Dat Do, the surrounding villages, Xuyen Moc and the supply bases in the north of the province.

The operation got into full swing on 15 July and continued until 1 August.

Though short it had a profound effect on the enemy and his capacity to resupply himself and conduct his operations. Also, Route 326 was reopened for civilian access to the fishing industry of Phuoc Hai. Windmills erected in Hoi My, Phuoc Hai, Phuoc Lot and Tam Phuoc produced a badly needed water supply system. A fence constructed round Dat Do made the supervision of the rice control program more efficient and effective; the bunkers placed round the villages and manned by RF and PF soldiers increased the safety of the civilians, especially along Route 44.

At the same time the effectiveness of the local administration, the police, and the RF and PF had been extended. Moreover, constant and vigorous patrolling and ambushing had mauled the D 445th Battalion and other guerilla units.

The experience of B Company, 6 RAR, commanded by Major Mick Harris, was typical. Operating independently, some distance from the rest of the battalion, Harris had deployed his company over a wide area to locate the enemy. Contact was quickly made. Following a series of successful engagements between 14 and 17 July, Harris established that there was an enemy base camp in the thick jungle nearby.

On 18 July the camp was located and skilful reconnaissance revealed the enemy was disposed in an extensive bunker system. Harris realised that normal preparatory fire support could result in the premature withdrawal of the enemy, so he decided to launch a silent attack. Next day the assault began, and while moving forward the company made three separate contacts. Harris continued with the assault, which, after moving 50 metres, came under heavy rocket, machine-gun and small arms fire. The momentum of the assault was maintained when Harris committed his small reserve. The enemy, subsequently found to be a battalion headquarters and an infantry company, fled, leaving their dead behind.

During 6 RAR’s operation 22 enemy soldiers were killed and five others, including the company commander of C 2/D 445th, surrendered; equipment, weapons and documents had been captured; base camps were located, and these the land clearing teams destroyed. Enemy movement from and to the Long Hais and the Light Green, tax gathering, resupply and recruiting throughout the area was now a difficult and dangerous occupation.

Regrettably, losses to the ANZAC Battalion had been high. Five had been killed in action and a further four had died of their wounds. Another 42, including the commanding officer, had been wounded. Two engineers had been killed while supporting the battalion, and twelve more were wounded. As with 5 RAR’s operations in the same area, most of these casualties were from mines. As part of the enemy’s own operations, these were placed in and around population centres and in areas where Australian and South Vietnamese troops were operating. The purpose was to diminish further the confidence of the people in the civil and military authorities. While much had been achieved during Mundingburra in mastering the techniques of finding and dealing with mines, the cost had still been high, and the battalions would continue to lose more men to them in future. Throughout the regiment’s involvement in the war it was mines that were detested most.

It will be remembered that the Horseshoe minefield and fence had been constructed in 1967. Its purpose was to assist in separating the enemy from their traditional sources of supply in the main population centres around Dat Do. Minefields must be covered by observation and fire in order to be effective and prevent enemy sappers from breaching it or removing mines for their own use. But the South Vietnamese units, which were now responsible for the security of the minefield, were neither patrolling nor observing it to the required degree. As a consequence, M16 mines were turning up all over the province, and Australian casualties were steadily increasing. One task force commander estimated that between September 1968 and May 1970 half of the Australian casualties were from our own mines. Finally, in February 1970 during operations in the Long Hais, 8 RAR suffered two mine incidents that caused the Chief of the General Staff to send a forthright signal to COMAFV. It was the last time that Australian troops operated there.6

A typical mine incident is recalled by the commander of A Company, 6 RAR/ NZ, Major Peter Belt:

It was 22 April 1970: our last operation, TOWNSVILLE, about three weeks before we came home. We’d moved into a new area south of Xuyen Moc, and there didn’t seem to be much current intelligence about it. I had three platoons out searching, with CHQ [Company Headquarters] by itself on a separate axis. The nearest platoon was about 300 metres away. It was fairly early in the morning—about 9 or 10 am— and we were following a faint foot-track out of the timber into a sandy area.

My FO, Lieutenant Bernie Garland, stood on it. There was this stomach lurching bang, then complete silence. Not a sound. But you knew instantly what it was, because many of us had been through it before. The immediate action on mines was to stand absolutely still—where there was one mine there were always others—then begin prodding your way out. Two people did move, though. My medic went straight to Bernie, and my CSM, Smiler Myles, came up from the rear because he thought it was me that’d trodden on it. Smiler was badly wounded himself—he’d been hit in the stomach by fragments. Besides Bernie and the CSM, both the FO signallers, my two Company sigs, and two others were wounded also. Even so, discipline, common-sense, and training exerted themselves, and we all began prodding.

After the initial shock I think it was the anger and frustration that was worst. If it had been a contact we could’ve fought the enemy on equal terms. Now we’d taken casualties without being able to retaliate. Our medic felt it most. Bernie had taken the full force of the mine about waist height: the main arteries of both legs had been severed and he bled to death in a very short time. There was nothing that would stop the bleeding. It was the third one our medic had lost in a similar way. Bernie’d been married in Singapore about ten days before.

Eventually we’d prodded ourselves out of the immediate area, then cleared a small pad for a helicopter, and my support section commander, Corporal Paul Peterson, got on the radio and organised a Dustoff. The first one came very quickly and took the casualties away. The second backloaded their weapons and equipment in a slung load, but as it lifted off it dragged the gear into the uncleared area. It was the only time we came close to panic.

The after-effects hit us that night. The APCs had pulled us out of the area and we were joined by the tanks. They put in a night harbour with CHQ and one platoon in the middle—they understood that we needed to be looked after. We all felt very tired, lethargic. It was difficult to take an interest in anything, even minor tasks took an enormous effort of concentration. It was probably the backwash of the adrenalin that’d hit our systems when the mine detonated. I suppose it was another three days before we got completely back to normal . . .

It’d been a bad day, though. A thing you don’t forget.7

Mines posed a constant threat against which vigilance was the only protection. But when lone platoons came upon an occupied enemy bunker system, the ensuing firefight demanded great skill and courage from young leaders if the platoon was to escape heavy casualties. For example, on 28 February 1970, a platoon from 6 RAR made contact with an enemy force well entrenched in a bunker system. Bitter fighting at very close range ensued. The enemy, later learned to be of battalion strength, directed rocket, claymore mine, machine-gun and small arms fire from very close range at the platoon, which suffered twelve casualties, including the platoon commander. Corporal Hans Fleer, twenty years old and on his second tour of Vietnam, skilfully directed covering fire onto the enemy position and reorganised his section. He then moved out under his section’s covering fire to initiate the recovery of the wounded men. Having extracted the wounded from their exposed position, he directed the withdrawal of the platoon. During the withdrawal another section came under heavy enemy fire, but with skilful use of fire and movement Fleer withdrew this section as well.

Eight days later 10 Platoon, 6 RAR was patrolling in very close country when signs were found indicating that there was an enemy defended position nearby. Shortly afterwards, newly constructed bunkers were sighted and, with one section deployed to provide fire support, the remainder of the platoon moved forward to investigate. Contact was made immediately with a well-entrenched enemy force. Sustained and accurate small arms and rocket fire was received from the left flank and a section commanded by Corporal Peter Ashton, a 21-year-old national serviceman, was ordered to cover the flank. In succession Ashton saw three of his soldiers fatally wounded while manning the section machine-gun. Realising that it was critical that the enemy fire in the area be suppressed, Ashton moved forward under heavy fire, retrieved the machine-gun, gathered the ammunition around it, re-sited the weapon, and then operated the machine-gun with great skill and accuracy. For the next 30 minutes he completely dominated the battle in his sector by fearlessly standing in the contact area and engaging every likely enemy position. Rallying the remaining three members of his section he advanced on the enemy, drove them from their positions and completed the section’s task.

In November 1969, 8 RAR, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Keith O’Neill, relieved 9 RAR, and in February 1970 7 RAR, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Ronald Grey, took over from 5 RAR for its second tour in Vietnam.

Keeping the Pressure on the VC

The pacification effort, begun in May 1969, continued with equal vigour throughout the following year, and the constant flow of documents captured by the battalions proved how successful this type of operation could be in a guerilla war. Nevertheless, the task force commander, Brigadier Stuart Weir, realised the need to mount major operations against enemy units in their base areas; it was essential to harass them relentlessly, to inflict maximum casualties, and to keep them always on the move and off balance.

Operation Concrete was one such activity. Beginning on 19 April 1970 and continuing through until 7 May, it committed to battle all three battalions of the task force: the 6th, 7th and 8th Battalions, with their normal supporting elements as well as A Squadron, 1st Armoured Regiment and B Squadron, 3rd Cavalry Regiment. The area of operations centred on Xuyen Moc, and the aim was the destruction of the D 445th Batallion, which had been given the task, throughout 1970, of undermining the pacification program.

The mission of 7 RAR was to carry out reconnaissance-in-force and ambushing throughout the enemy base area known as the Tan Ru. Lieutenant Colonel Grey’s plan was to insert the companies on foot, thereby obtaining a degree of security impossible when sub-units were air-landed. It was a technique that had been used frequently by the battalions in Phuoc Tuy, and it invariably yielded quick results in the early stages of each operation.

On 15 April C Company was detached to 1 ATF to continue the training of units of the 18th ARVN Division at the Horseshoe, and in addition was tasked to patrol out from there and to ambush. On 19 April A and B Companies left Nui Dat on foot, while D Company moved first to the Horseshoe in APCs and then dismounted to complete the deployment to an area north of Nui Nhon. On the 20th, Support Company, followed by Battalion Headquarters, moved in APCs to FSB Discovery, four kilometres north of Route 23 along Route 328, and all deployment was complete by midday.

At 1.45 pm that day 4 Platoon, B Company contacted six enemy four kilometres west of the FSB, killing one enemy soldier while the others fled. On 22 April at 1.15 pm, B Company saw two more enemy not far from 4 Platoon’s contact.

Pursuing them, the company began the battalion’s first bunker battle, which continued throughout the afternoon supported by artillery and air strikes. A troop of Centurions joined the battle at 6.12 pm, but by then the light was fading. During the night B Company sent out patrols to the east to cut likely enemy withdrawal routes from the bunker complex, and at first light they assaulted and occupied it.

There were the inevitable blood trails and dressings to show that the enemy had suffered casualties, and captured documents indicated that C 3/D 445th and K 6/D 440th Battalions had defended the position.

Meanwhile C Company, based at the Horseshoe, had not been idle. On Anzac Day a twelve-man patrol from the company ambushed a well-armed group of 50 to 60 enemy outside the village of Lang Phuoc Hai. Skilful use by the patrol commander of artillery, air, and a tank troop forced the enemy to withdraw leaving several dead behind them. A search of the bodies showed them to be members of the Phuoc Hai and Long Dat guerilla units.

Contacts continued until 7 May, when the operation finished. In all, nineteen enemy had been killed, three wounded, one taken prisoner and another had surrendered. In addition, numerous bunkers were located and destroyed and an assortment of weapons and equipment was captured. Two infantrymen of the battalion were killed and nine wounded, one of whom subsequently died. But the battalion had achieved all its aims, as had 6 RAR and 8 RAR; the enemy had been pursued relentlessly; been harried in and around their base areas; and had lost more men and equipment, as well as their freedom of movement.

Concrete was the last operation for 6 RAR, which in May 1970 was replaced by 2 RAR, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Church. Shortly before the changeover of these two battalions, the Prime Minister, John Gorton, announced on 22 April that 8 RAR would not be replaced when the battalion departed in November. Thereafter the number of infantry battalions in 1 ATF would remain at two. Mr Gorton also said that this partial withdrawal would require some modification of the role played by the task force in Phuoc Tuy. This modification, he said, was made possible by the success of Vietnamisation in the province. However, the new task force commander, Brigadier Bill Henderson, was sceptical. As the time neared for 8 RAR to depart, he said that ‘Withdrawal will merely mean that we will have to work very much harder than at the moment, which is already pretty hard.’ And in November he commented again that ‘although the Vietnamese forces were now more efficient, the withdrawal of the 8th Battalion had not in any way altered the role of the task force. The problem is that we still have the same area to cover.’8 During its tour in Vietnam, 8 RAR lost eighteen members killed in action. On 29 October 1970, shortly before leaving Vietnam, the battalion was presented with the Meritorious Unit Commendation of the Vietnamese Armed Forces.

A major operation in the second half of 1970 was Operation Cung Chung (Together), involving cooperation between the Australian battalions and the local South Vietnamese forces, in pacification operations in the east of the province. 7 RAR was heavily involved in the various stages of the operation which lasted for some months. This photograph shows Private Darryl Blackwell of 8 RAR and a South Vietnamese national policeman examining each other’s weapons while resting after a village search in July 1970 (AWM photo no. FAI/70/554/VN).

Mr Gorton’s announcement in April came at a time when task force operations had again shifted in emphasis; the sustained effort against D 445th and D 440th Battalions in the period September 1969–April 1970 resulted in those units becoming essentially inactive, and subsequently they were removed from the province for rest, reinforcement and retraining. At about the same time American operations began in Cambodia, and caused shortages in the resupply of weapons and ammunition to the enemy units in and around Phuoc Tuy. Accordingly, Brigadier Henderson decided to deny the enemy any chance of resupply by close ambushing of the principal villages throughout the province, especially Dat Do and Hoa Long, of which 8 Platoon’s ambush, recounted at the beginning of this chapter, was an example.

Another was an ambush of seventeen men from 2 RAR, commanded by Second Lieutenant Peter Gibson, near the Courtenay rubber plantation on 15 December 1970. At 9.00 pm a group of about twenty enemy approached the ambush and were engaged with claymore mines and fire from the one machine-gun carried by the patrol. A firefight, which lasted for 45 minutes, ensued between the enemy group and the patrol. The enemy fled leaving ten dead on the battlefield. The patrol suffered two lightly wounded casualties. By no means all the ambushes mounted were so successful, however. Ambushing is one of the most difficult operations of war, and luck, as well as good planning and preparation, is an essential ingredient.

Indeed most ambushes yielded little more than long hours of discomfort.

On 1 February 1971, 2 RAR/NZ Battalion began Operation Phoi Hop (Cooperation), which saw the handover of a large part of the battalion’s AO to RF and PF units, including the Rung Sat Special Zone and the area round Hoa Long. On 20 February RF units were also given responsibility for the area of Phuoc Tuy from the Nui Dinhs to Route 23 southwards, and this marked the final change in emphasis in the operations of the task force. With South Vietnamese forces now responsible for the security of the major centres of population, the battalions were once more free to turn their attention to seeking out their old adversaries: the D 445th Provincial Mobile Battalion, the 274th VC Regiment and the 33rd NVA Regiment.

Return to Main Force Operations

On 25 February the main body of 3 RAR arrived to replace 7 RAR. Commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Peter Scott, the battalion was given the responsibility for the eastern half of the province, except for the areas immediately around the villages. At the same time 2 RAR/NZ Battalion took responsibility for the western half.

In March the D 445th was reported to have left the May Tao Hills and re-entered the province after its period of rest and retraining. Throughout March and April 2 RAR/NZ and 3 RAR worked together recording several fierce contacts with the newly reconstituted Provincial Mobile Battalion. Captured documents identified the main body of the D 445th, and indicated that the mobile battalion’s most likely mission at this time was to mount an attack in the Duc Thanh area.9 In May 2 RAR departed for home, and was replaced by 4 RAR, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Jim Hughes.10 Also in May, and again in June, intelligence reports indicated that the D 445th and the 33rd NVA Regiment were located to the east of Route 2 along the border between Phuoc Tuy and Long Khanh. Their aim was the disruption of the continuing pacification program and its concomitant, Vietnamisation. On 5 June 1 ATF therefore mounted a ‘hammer and anvil’ operation, titled Overlord.

For this, the rifle companies of 4 RAR/NZ Battalion were deployed along the line of the Suoi Ran, with A Squadron, 3rd Cavalry Regiment to their west, and 2/8th Battalion, 3rd Cavalry Regiment (US) to the north-east. The tanks of C Squadron, 1st Armoured Regiment and 3 RAR were given the task of driving the enemy onto these blocking positions. But although B and D Companies of 3 RAR made contact with the 3/33rd, C Company found 31 bunkers which had been occupied by the D 445th, and the ANZAC Battalion reported small groups of enemy trying to penetrate their blocks, the operation yielded little.

Operation Hermit Park followed immediately and 4 RAR was this time better rewarded. The area of operations was the north-east of the province along both sides of Route 2. Contact was made with 274th Regiment, and 1 Troop, A Squadron, 3rd Cavalry, who were under command of the battalion, mounted an APC ambush which contacted 25 members of Sub-Region 4, killing thirteen of them and capturing five others. A bunker system belonging to the Chau Duc guerillas was seized and destroyed; and finally V, B and C Companies located the headquarters of the 274th Regiment in a system along the Suoi Quit and forced their withdrawal.

On 28 July, 3 RAR and the ANZAC Battalion deployed for Iron Fox, another task force hammer and anvil operation. Now 3 RAR provided the blocking positions west of Route 2, and on the afternoon of 29 July and again next day, C and D Companies of 4 RAR, accompanied by the tanks of C Squadron (again demonstrating that tanks can be used in jungle to great advantage), fought lively battles with the 1/274th along the Song Ca. By the end of these operations on 5 August, the plans of the 274th Regiment to set up bases in the north-west of the province and use them for attacks along Route 2 had been completely disrupted. Nevertheless the task force commander, now Brigadier Bruce McDonald, maintained the pressure: Operations North Ward, Inverbrackie and Cuddle Creek kept up relentless pressure on the enemy along both sides of Route 2 in the north of the province.

On 18 August 1971, the Prime Minister, William McMahon, announced that 1 ATF would cease operations in October, and that 1 ALSG would be withdrawn from Vietnam by the following March. It was planned that 3 RAR would depart aboard HMAS Sydney on 6 October, and that 4 RAR would go the same way on 8 December, leaving behind their D Company to secure the 1 ATF/ALSG base at Vung Tau until that too ceased to operate on 29 February 1972.

One of the first units to be withdrawn, much to the regret of the battalions, was the men and tanks of C Squadron. The respect and admiration in which the tanks were held by the infantrymen is summed up in a letter from the commanding officer of 4 RAR to the tank squadron commander:

The effort and outstanding esprit-de-corps of your unit have truly been a major factor in the operational success of 1ATF combat units. There is no doubt in my mind that casualties would have been much greater without your unfailing sup port and willingness to accept calculated risks to assist my men, especially in bunker contacts and thereby carry the day in the true spirit of armoured/infantry cooperation.11

Before the withdrawal of the task force, though, there was still one more major battle to be fought. During Operation North Ward, which lasted from 5 August to 18 September, V Company of the ANZAC Battalion contacted sappers of both the Chau Duc and Ba Long units. A short time later D Company ambushed a senior cadre member of the Ba Long Province Headquarters; and C Company located freshly constructed bunkers in the Song Ca–Suoi Soc areas where contact with the 274th Regiment had been made on Operation Iron Fox in July. At the same time mine incidents and ambushing by the enemy of civilians and RF units along Route 2 became commonplace. In the second week of September D Company in the Nui Le area found foot-tracks of groups of enemy moving east to west, and as a result of minor contacts reported the enemy to be navigating, unusually, with the aid of maps and compasses. No unit identities could be established from these sightings and contacts, and this fact was also unusual and disquieting.

Obviously something was going on, but just what that might be was as yet unclear.

As 4 RAR’s history comments, ‘it was apparent that a new and active force had commenced reconnoitring the area, and shortly afterwards, Operation Ivanhoe was commenced . . . this operation will be hard to erase from the memories of those who participated’.

In the small hours of 19 September, the 626 RF post on Route 2 received an attack by fire from 75 mm recoilless rifles and 82 mm mortars, and at the same time the village of Ngai Giao came under sapper attack. Early on the 20th, a detachment of APCs from 1 Troop, A Squadron, 3rd Cavalry was ambushed on Route 2 by approximately twenty enemy soldiers using RPGs and small arms fire. Meanwhile there were minor contacts for D Company, 4 RAR under the shoulder of Nui Le, but as one platoon commander observed, things ‘started to look decidedly spooky . . .’.12 Then, early on the 21st, D Company, commanded by Major Jerry Taylor, found itself in the middle of a large bunker complex occupied by the 2/33rd NVA Regiment, while Major Bob Hogarth’s B Company came into heavy and sustained contact with the 3/33rd about four kilometres to the south. These battles raged all day and well into the night, when, as was so often the case, the enemy melted away.13 According to a platoon commander of C9 Company, 3/33rd who was captured later, what had happened was that the attacks on the RF post and the APCs on 19 and 20 September were part of a plan to lure the 1 ATF Ready Reaction Force into an area where it could first be ambushed by the 3/33rd, then brought north to the Nui Le–Nui Sao bunker system where a resounding defeat would be inflicted. However, when D Company made contact with Regimental Headquarters and the 2/33rd in the north, the 3/33rd was ordered to abandon its ambush position in the south and withdraw. It was during this withdrawal that the enemy found themselves confronted by B Company. The enemy had been defeated and forced the 33rd NVA Regiment to abandon its local efforts, but it had been a near-run thing.

The last operation conducted by 1 ATF was appropriately named South Ward and was the withdrawal from Nui Dat to Vung Tau. On 6 October, 3 RAR boarded HMAS Sydney for the return journey to Australia, having had four members killed in action during its eight-month tour. In early October 1971, control of all operations in Phuoc Tuy was handed over the province chief. After the bulk of the task force moved to Vung Tau 4 RAR was given the responsibility for the security of Nui Dat and the immediate surrounding area. On 16 October the ANZAC Battalion was retitled 4 RAR/NZ (ANZAC) Battalion Group, and now consisted of the battalion; 104th Field Battery; 1 Troop, A Squadron which included a detachment of fire support vehicles; 1 Troop, 1 Field Squadron; a detachment from 161 Renaissance Flight; a forward air traffic operations centre; personnel from 10 Military Intelligence Detachment; and some service detachments.

Before the battles of 21 September, and increasingly after, there had been much debate in Parliament and the media as to the safety of Australian troops during this most critical time of withdrawal. The activities of the enemy in the north of Phuoc Tuy in September and the casualties there (five Australians had been killed and another 29 and one New Zealander were wounded) led to speculation that there might be a serious effort made to interfere with the withdrawal. It was therefore now even more important to maintain an appearance of normal activity in and around Nui Dat. Even though the area round Nui Dat continued to be quiet there was little need to remind the battalion group of the importance of aggressive and sustained vigilance.

On 6 November the battalion’s advance party, together with all bulky or heavy items, completed an uneventful administrative move to Vung Tau, leaving only the fighting elements at Nui Dat for one more night.

It was planned that the 946th Regional Force Company would take over SAS Hill as soon as D Company withdrew next day. To that end a platoon from the RF Company came up as an advance party on the last evening. As a member of D Company recalls,

They wore an assortment of uniform, civilian clothes, and webbing, all in varying degrees of shabbiness and disrepair. One of them had the torso of a monkey wired to the foresight of his M16: his evening meal, presumably . . . I felt overwhelmingly sorry for them. I think we all did, because nobody said anything and nobody laughed.14

Next day, 7 November 1971, the battalion group left Nui Dat for the last time and made an unchallenged withdrawal to Vung Tau. In four months of operations, 4 RAR/NZ had lost nine men killed, including one New Zealander.

There was still much to be done before the battalion left: the cleaning, accounting for, and packing of stores and equipment into Conexes; personal trunks to be painted and addressed; malaria eradication courses to be completed by all, and blood tests for those who felt they needed them; and the briefing and reinforcement of D Company, which was to remain behind for another three months. And there was, inevitably, much socialising to be done, during which the members of all messes said goodbye to their many friends. Upon departure those aboard HMAS Sydney were farewelled by President Thieu, and Lieutenant Colonel Jim Hughes received a signal from the Colonel Commandant of the Royal Australian Regiment, Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Daly, which he passed on: ‘[M]y sincere congratulations on the success of your tour of duty in Vietnam. 4 RAR is the last battalion to leave Vietnam and as such has written with distinction the final chapter in the splendid story of the Regiment’s participation in the Vietnam conflict.’

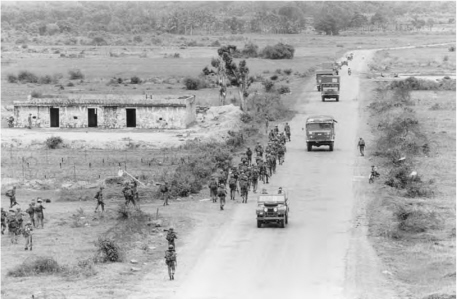

The changing of the guard at Nui Dat in October 1971. For more than five years the battalions of the regiment had occupied the task force base at Nui Dat. While troops of the task force move south by vehicle along Route 2 towards Vung Tau as a further stage of the Australian withdrawal from Vietnam, South Vietnamese troops move north to take over the Australian positions (AWM photo no. FOO/71/513/VN).

Now, as Sydney sailed out of Vung Tau harbour, the D Company Group was on its own. On a continuous basis the company was required to have a platoon at fifteen minutes’ notice to move, with the remainder ready to follow within the hour, though where they would go, what they would do when they got there and what artillery or air support would be available, was never revealed. But, as luck would have it, D Company was ‘reacted’ only once during those three months, and after an anxious hour was stood down again.

Nevertheless there was a compelling need to keep everyone usefully employed. So three one-month courses were devised: mortar, signal and a general course which required all ranks to pass their battle efficiency, weapon handling, and shooting tests, and to practise battle first aid and other individual skills. These were conducted each morning, the afternoons being devoted to sport, for which there were excellent facilities at the Badcoe Club, where the company was accommodated. There was even an inter-platoon swimming carnival at which the company’s Vietnamese typist presented the prizes clad in a barely perceptible bikini.

The company’s rugby and cricket players went regularly to Saigon to compete against combined teams from the Australian, British and French embassies. There was also a nearby orphanage, run by Catholic nuns, and to this the men of D Company supplied unskilled but willing labour. And, as the withdrawal gathered pace, the company also provided stevedoring parties to help load the various ships which took heavy equipment and stores back to Australia.

At last, though, the moment for D Company Group to withdraw from South Vietnam arrived, and by lunchtime on 29 February 1972, everyone was safely aboard the Sydney.

The regiment’s involvement in the Vietnam War demonstrated yet again, if such is necessary, that the brunt of the battle falls on the infantrymen. It proved, too, that while techniques and weapons change, the basic skills do not. Physical and emotional fitness and toughness are of fundamental importance; so is the ability to handle weapons swiftly, instinctively, and with maximum effect under all conditions. As is always the case, it demonstrated the need for decisive and resolute leadership at all levels; plans and orders that are clear and unambiguous; and the determination, ability and offensive optimism of everyone concerned to carry those orders through to a successful conclusion. Training was culminated there and the lone months of individual, sub-unit and unit training in Australia, which may have seemed grinding at the time, bore good results in battle.

Nevertheless, the efforts and results of the infantrymen of the regiment would not have been nearly so noteworthy without those who supported them; artillery, armour, cavalry and engineers spring most readily to mind, but their efforts too would have been only partially successful were it not for the vital contribution made by the corps and other servicing units; by the troop-lift, gunships, and casualty evacuation aircraft flown by the RAAF and the Americans. The part played by the infantrymen of the RNZIR as members of the ANZAC Battalions, and the RNZ Artillery, was also a significant one.

As HMAS Sydney got under way, groups of men from D Company gathered at her stern and stood watching as the unhappy coastline of Vietnam receded. After a while it could only be seen as a thin grey line, except where the hills of Phuoc Tuy thrust up. Soon even they had vanished beneath the rim of the sea.