13 Ready Reaction and Specialisation Australia, 1980–90

David Horner

The beginning of 1980 brought fundamental changes in the role and organisation of the regiment’s six battalions. There were two key concepts: the introduction of battalion and brigade specialisations, and the formation of a rapidly deployable ready reaction force available for use by the government at short notice. The introduction of these concepts and specialisations took a few years to complete, but the result for one battalion was vividly demonstrated by the events of May 1987.

May 1987 was the 22nd anniversary of the deployment of 1 RAR to Vietnam. Since the final withdrawal from Vietnam in February 1972 the regiment had been involved in peacetime activities for fifteen years. Members of the regiment had served with UN peacekeeping forces in the Middle East and Kashmir, and had contributed to the Commonwealth Monitoring Force in Rhodesia in December 1979 and the Commonwealth Military Training Team in Uganda in 1982–84. The possibility of active service, however, seemed remote. The military coup in Fiji on 14 May 1987 was to shatter the belief of many that in the midst of peace the regiment was unlikely to see operational service for many years.

The Operational Deployment Force (ODF), based on the 3rd Brigade in Townsville, had been raised in 1980 to provide a ready reaction force. As the events in Fiji unfolded in May 1987, the brigade commander, Brigadier Peter Arnison, and the commanding officer of 1 RAR, Lieutenant Colonel John Salter, were attending an exercise in north-west Australia. In addition, four company commanders, four company sergeant majors and seven platoon commanders were absent from the unit, while one company was on exercise in Hawaii. As usual, a company was on seven days’ notice to move, but Major Gary Stone, the battalion second-in-command, had been given no indication that any deployment was being considered. Indeed the brigade was specifically told that there would be no army involvement in Fiji, and there was to be no unit activity that might unduly alert the public.

Then, without warning, at 9.30 am on 21 May Stone was called to Brigade Headquarters, where the brigade major ordered him to bring the advance company group (B Company) to immediate readiness for possible air deployment to Fiji to assist with the evacuation of Australian nationals. There was to be a deception plan and no one below the rank of major was to be informed of the operation. Returning to the battalion, Stone assembled a small planning group, and at 1.00 pm he issued battalion orders. At 3.42 pm a formal warning order from Land Command placed the company group on two hours’ notice to move from 3.00 pm. Subsequently, 4 Platoon was recalled from the High Range Training Area, and since B Company had only 79 men available, reinforcements were obtained from the remainder of the battalion.

Stone was increasingly uncomfortable with the requirement to maintain secrecy and to keep from the troops the fact that in a matter of hours they might be embroiled in a civil war. Then at 5.30 pm the local radio station broadcast an announcement from the Prime Minister that an ODF company had been placed on stand-by to deploy to Fiji. But it was not until 7.00 pm that Stone obtained permission to advise the troops of the operational situation. Half an hour later he formally advised the B Company soldiers that they had been ‘warned for operational service in the Fiji area. We are to deploy to Fiji to provide protection to Australian nationals and protect the evacuation of Australian nationals from Fiji.’ The company was to fly by C–130 to Norfolk Island, where it would rendezvous with a naval task force. As Stone recalled, ‘there was stunned silence and I could almost hear their hearts pounding. There was still lots to be done; equipment to be tested, personal property to secure, farewells to be said. We worked through the night.’

Within seven hours of warning B Company was ready for deployment, but it did not begin to fly out of Townsville until 7.30 am on 23 May. Although Lieutenant Colonel Salter had returned from Broome, Stone was appointed contingent commander and the company commander was Major Bruce Scott, originally officer commanding D Company. The 1 RAR group arrived at Norfolk Island late in the afternoon of 23 May and began transferring to HMA Ships Success and Tobruk. On 26 May the troops in Tobruk were transferred to Success, Sydney and Parramatta on the RAN patrol line fifteen nautical miles south-west of Fiji. They remained on station until 29 May by which time the situation in Fiji had stabilised and the Australian force began to withdraw.1 By 7 June the contingent was back in Townsville and the following week the Prime Minister, Bob Hawke, and the Minister for Defence, Kim Beazley, visited the battalion to thank it for its contribution. The visit afforded the RSM, WO1 ‘Blue’ Milham, some notoriety when he announced the Prime Minister to the assembled battalion in the other ranks’ mess as ‘The Prime Minister of Australia, the Honourable Bob Menzies’. The RSM had been reminiscing shortly before about a time early in his career when Sir Robert Menzies had visited 1 RAR.

Operation Morrisdance in May 1987 involved the deployment of a company group of 1 RAR in RAN ships off the coast of Fiji to evacuate Australian nationals if that became necessary. It was an excellent validation of the battalion’s operational readiness. Corporal Williamson, B Company, 1 RAR disembarking from HMAS Parramatta in June 1987 after returning from the operation (photo: 1 RAR).

Operation Morrisdance, as it was known, was a validation of the battalion’s operational readiness. With minimal notice the company group had been deployed by air and sea some 4000 kilometres to undertake tasks that had not been specifically addressed in training. The deployment was not, however, without its problems. Rifle sections that had trained with nine men deployed with only seven or eight men. There were shortcomings in the level of training for the specific tasks and in the state of equipment and stores within the battalion. Except for the MAG 58 machine-gun the other weapons were the same as those carried by the regiment in the jungles of Vietnam.

There were also difficulties with joint service procedures. The battalion officers believed that the navy lacked an understanding of army operations, and that some of the directions from Canberra indicated a lack of understanding of the ODF’s methods. HQ ADF staff in Canberra, however, believed that the difficulties were due as much to the army’s lack of training with the navy, and that political requirements overrode the wishes of the ODF.2 Nonetheless, when the problems of preparing 3 RAR for operations in Korea in 1950 and 1 RAR for operations in Vietnam in 1965 are recalled, it is clear that despite a rather benign strategic environment and little operational experience, the readiness of this part of the regiment in the 1980s revealed a high level of professionalism.

The battalion’s ability to react quickly and effectively in May 1987 was not developed overnight, but was the result of a deliberate policy that had begun almost ten years earlier. As described in the previous chapter, by the end of the 1970s the battalions had acquired greater versatility, and were well on the way to mastering the skills and developing the capabilities needed to fight over open spaces and vast distances. But there was little correlation between defence policy, strategic concepts and battalion training. A new direction was required.

The impetus for change had come with the appointment of Lieutenant General Donald Dunstan as Chief of the General Staff in April 1977, barely five months after the release of the government’s White Paper, Australian Defence. The paper emphasised a policy of self-reliance in which it was no longer expected that Australian forces would ‘be sent abroad to fight as part of some other nation’s force, supported by it’. The government did ‘not rule out an Australian contribution to operations elsewhere if the requirement arose’, so long as Australia’s presence would be effective and forces could be spared from their national tasks. But it believed that operations were ‘more likely to be in our own neighbourhood than in some distant or forward theatre’, and that they would be conducted as joint operations by the ADF.

This policy posed difficult problems for army planners, and since Australia’s was essentially an infantry army, these problems were strongly reflected in the regiment. The White Paper stated that the first element of the government’s policy was ‘the maintenance of a substantial force-in-being, which is also capable of timely expansion to deal with any unfavourable development’. But what was the shape to which the army had to expand? What was the threat for which the army had to prepare? And what were the tasks that the army might need to undertake in peace?

These questions took some years to resolve, but in the meantime Dunstan realised that he could not afford to wait for direction from the government or the Department of Defence. By November 1977 he had concluded that despite the fact that the 1st Division had been restructured at the end of the Vietnam War to improve the army’s capability to operate within Australia, it needed further modification. First, the organisation was too heavy in both manpower and equipment; it needed to be trimmed down. Second, the army was losing its expertise in operating on light scales; the division was becoming tied to trucks and APCs and Dunstan believed that at least part of the army had to be capable of moving quickly and without heavy equipment. And third, the army was losing its expertise in operating in tropical terrain; there had been no progress in developing close country warfare techniques beyond those used in Vietnam, and new technology had not been exploited. Further, the Australian Army might need to operate in northern Australia in the wet season, which posed particular mobility difficulties.

Dunstan explained later that the big problem was the distribution of limited resources between the expansion base and the requirements for contingency deployments. After Vietnam the army had been kept broadly based, spreading resources evenly in the expectation that it could regroup for a task as it arose. But the reaction time was too slow. As he put it: ‘I could not guarantee to provide a task force of two battalions in less than about three months, or a battalion group in less than a month.’3 On 25 June 1979, the Chief of the General Staff ’s Advisory Committee (CGSAC) endorsed a proposal that the 3rd Task Force in Townsville, comprising 1 RAR and 2/4 RAR, become the nucleus of an operational deployment force that would be on short notice to move. One battalion was to be the vanguard to move ahead of the rest of the ODF. The task force was to be placed on a tropical establishment and was to train for tropical warfare. It had to develop a particular capacity to operate on light scales and be air portable in medium range transport (C–130 Hercules aircraft).

The 6th Task Force (6 RAR and 8/9 RAR) at Enoggera Barracks in Brisbane was to specialise in open country warfare, establish a limited parachute capability, and also train for operations in built-up areas. It was to be prepared to provide a battalion to the 3rd Task Force on the same degree of notice as the rest of the ODF.

The 1st Task Force at Holsworthy near Sydney was to develop a capability for armoured and mechanised infantry operations, involving the eventual mechanisation of 5/7 RAR at Holsworthy, and exercises with the 1st Armoured Regiment, based at Puckapunyal, north of Melbourne. Meanwhile 3 RAR, then located at Woodside, South Australia, was to move to Holsworthy, eventually to become part of a mechanised brigade.4 By September 1979 Dunstan had a paper prepared for the Minister for Defence in which he argued for ‘changes in the organisation, role and training of 1st Division’. Dunstan explained that until recently the army had considered that the skills, techniques and equipment for special roles could be readily adapted from the standard organisation and training. But he had now concluded that this was not always the case. Armies were sensitive to the terrain and climate in which they operated, and therefore ‘a combat formation which enjoyed a high mobility in one area could become immobile in another; or indeed in the same area with changes in season, such as are found in the north of Australia’. The army had to be trained and equipped for a wide range of environments. Dunstan concluded that there was a requirement for three basic specialisations: ‘a light organisation, air portable, tactically air mobile and air supportable’, which was also trained to deploy by sea; ‘a standard infantry organisation which would become the repository of the state-of-the-art of conventional infantry operations’; and ‘an armoured/mechanised organisation to develop the tactics and organisations appropriate to mobile ground operations in Australia’. The army envisaged ‘light’, ‘medium’ and ‘heavy’ task forces, as the task force was the lowest organisational level where the necessary all-arms components might be brought together to develop and test doctrine, tactics and procedures.5 Dunstan’s proposal reached the Cabinet at almost precisely the time that ministers were dealing with the international crisis caused by the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in late December 1979. Earlier that year China had attacked Vietnam and had received a painful rebuff in a series of bloody border engagements. Then the Shah of Iran had been overthrown in a revolution that led to an increase in the worldwide price of oil. In October President Park of South Korea had been assassinated, and this was followed by civil disturbance and the restoration of order by the armed forces. Also, during the year, the Soviet Union had continued the deployment of its SS20 missiles in Europe.

These events had important implications for Australian defence, and in a speech to Parliament on 19 February 1980 the Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser, pointed to the consequences of the Soviet move: ‘Russian military power is now 250 miles closer to the Gulf than it was two months ago. It is now within 300 miles of the Straits of Hormuz, the choke point through which the bulk of the world’s oil supply must move.’ A month later Fraser reminded Parliament that ‘It would be folly to believe that the events which have culminated in the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan leave our longer term strategic prospects unaltered.’

The government responded quickly to this changing strategic climate and in March 1980 the Defence Minister announced an increase in Defence spending of about 7 per cent a year in real terms over the next five years. The Army Reserve was to be expanded to a strength of 30,000 by mid-1981. The government decided not to accede to a request from the US government to commit forces to the US Rapid Deployment Force, then being put together for possible operations in the Middle East, but the episode focused discussion on the need for Australia to possess such a force.

On 21 February 1980, the government announced the reorganisation of the 1st Division. In essence Dunstan’s plan had been accepted and the government had decided to provide resources for a further 850 men, thus bringing the 3rd Task Force, with its two battalions, up to full strength. Both 1 RAR and 2/4 RAR were to be expanded to their war establishment of four rifle companies. Priority was to be given to the development of the ODF brigade, based in Townsville.

The Operational Deployment Force

In anticipation of this decision, in 1979 the 3rd Task Force commander, Brigadier Ray Burnard, had nominated 1 RAR as the first battalion to be prepared for the ODF role. When Lieutenant Colonel Pat Beale had assumed command of 1 RAR in December 1978, he had found a battalion of three rifle companies with a reasonable strength and well trained for operations in open country. But only 27 officers and NCOs had served in Vietnam, and there was a very low level of experience in jungle warfare.

Beale saw two priorities. First, the battalion had to be prepared to operate in any of the areas to which it could be deployed, including tropical and jungle areas. And second, the battalion had to be prepared to deploy with little notice. Beale therefore began re-establishing the skills necessary to operate successfully in the jungle, and training moved from the more open terrain of the High Range Training Area to the close country of Mount Spec, north of Townsville. For the young soldiers it was a new, and to some, disconcerting experience, to move into thick jungle, where navigation depended more on compass and pacing than map reading. As of old, rations again had to be carried on the back; no longer were hot meals brought forward by vehicle from A Echelon each evening. Contact and ambush drills had to be practised. And platoon commanders had to learn to operate independently from their company headquarters.

Meanwhile, the battalion second-in-command, Major Jim Connolly, was writing the orders to enable the battalion to deploy quickly by air. Load lists had to be prepared, equipment shortfalls identified and rectified, and each soldier had to have his personnel administration finalised; that is, he needed to be dentally and medically fit, have his inoculations brought up to date, and provision had to be made for the care of his family and effects should he be deployed at short notice.

Recalling his experience with 3 RAR in Malaysia in 1964 and 1965, Beale was determined that his battalion should be ready for action within 24 hours of orders being given, even though he was not required to be ready with such short notice.6 By January 1980, when the battalion was to assume the ODF responsibility, Beale was confident that he could provide a well-trained force at short notice. During the early months of 1980 the battalion was quickly brought to full strength. The fourth rifle company already had its complement of officers and senior NCOs. Trained soldiers, initially to bring three companies to war establishment, were posted in from the battalions in Brisbane and Sydney. On 29 March the 10th Independent Rifle Company (RAR) at the Land Warfare Centre, Canungra was reduced from an establishment of 60 personnel with two platoons to one platoon with 40 men to provide soldiers for the 3rd Task Force.

The commanding officer of 8/9 RAR, Lieutenant Colonel Fred Pfitzner, recalled that the demand for soldiers caused ‘a lot of heartburn’ in both 6 RAR and 8/9 RAR. ‘I determined to send a fair cross-section of experience, quality and talent to the north’, he said, but ‘the build-up of the ODF had a debilitating effect on 8/9 RAR. By the time I handed over the battalion to Rollo Brett its strength had reduced to some 500 men, from a take-over high of, as I recall, about 650 or so.

Under Rollo the battalion dwindled in 1981 to a low of some 450—arguably the most difficult time in the battalion’s history.’7 As far as the ODF soldiers were concerned, initially the new role had little impact.

In dress, personal equipment and weapons the soldiers appeared little different to those who had served in Vietnam ten years earlier. They still wore green uniforms, carried SLRs and M16s, and were equipped with M60s, M72s, M203 grenade launchers and Carl Gustavs. After years of use the M60 machine-guns were in poor condition and much of the soldiers’ personal equipment was shoddy. However, as the ramifications of the ODF duty became obvious, it gave the soldiers a great sense of purpose, and they responded well, buying equipment from disposal stores to rectify army supply deficiencies.

In July 1980, new establishments were announced for the regiment’s battalions. The ‘standard’ battalion establishment was to apply to 3, 5/7, 6 and 8/9 RAR, while 1 and 2/4 RAR were to adopt a ‘light’ establishment. The war establishment of each battalion comprised four rifle companies, a support company and an administration company. Support Company consisted of mortar, sustained fire machine-gun, assault pioneer and signals platoons. (A little later the anti-armoured platoon was restored to the standard battalion.) The main difference between the standard and light establishments was that the standard battalions had 43 light and seventeen medium vehicles while the light battalions had only 39 light vehicles and no medium vehicles. The standard battalions had 38 officers and 710 other ranks, while the light battalions had 36 officers and 644 other ranks.

The practical difference was that the light battalions of the ODF were manned to war establishment (680 personnel) while the standard battalions were restricted in peace to three rifle companies and the support company platoons were reduced accordingly; the battalions were restricted to a strength of 547. In 8/9 RAR the 106 mm RCLs were retained after Corporal Fred Remin gave Major General Ron Grey, GOC Field Force Command, a forceful ‘over the barrel’ briefing. In the standard battalions the fourth rifle company sometimes had its complement of officers and senior NCOs and became the training company for the battalion. Of course battalion commanders continued to make their own modifications; for example, in 1 RAR Beale raised a reconnaissance platoon, which he considered important for the operations likely to be faced by the ODF.8 At the beginning of 1980 Brigadier Neville Smethurst assumed command of the 3rd Task Force and in May 1980 he received his directive for raising the ODF. His primary objectives were to develop a capability for operations on light scales, and to be ready to deploy the task force element of the ODF. His secondary objectives were: to develop a capability for operations in tropical areas including jungle warfare; to develop the capability for amphibious deployment; and to be prepared to undertake tasks in aid to the civil power. For protracted deployment within Australia or overseas he was required to maintain a company group, including an administrative support element, at seven days’ notice. The remainder of a battalion group, including administrative support, was to be maintained at fourteen days’ notice, while the balance of the task force was to be at 28 days’ notice.9

These capabilities could not be developed quickly. During the 1970s battalions had trained for conventional operations in open country in a divisional setting, and had developed procedures, establishments and equipment to facilitate these operations. For example, the divisional artillery was commanded centrally by the divisional artillery commander so that the full weight of fire could be directed to the most appropriate area. Similarly, the combat elements of the division expected to be resupplied through the normal divisional administrative system supported by the lines-of-communications units, and these supplies were to be brought forward by the divisional transport resources.

The ODF, however, had to be able to operate independently. It was envisaged that the main combat element of the ODF would be the two infantry battalions of the 3rd Task Force with the capability of being reinforced by another infantry battalion from 6th Task Force. These battalions had to be air portable and therefore needed to readjust their establishments to eliminate much of their dependence on wheeled transport. The main form of wheeled transport would have to be the Land Rover, which was easily carried in the RAAF Hercules. To provide battlefield mobility once the ODF was deployed it would have to rely on utility helicopters, more of which would have to be stationed in Townsville for training and to develop the close working relationship that would be necessary in operations. The ODF would require its own organic fire support (it would not be able to rely on centrally controlled divisional artillery) and this would have to be transported by air. The task force would also have to develop the ability to command and deploy a small brigade maintenance area. Smethurst was the driving influence in getting the task force moving, and at the beginning of 1981 an additional major (OC Brigade Maintenance Area) was added to his staff to facilitate ODF planning.10

While the 3rd Task Force formed the main component of the ODF, the ODF was somewhat larger than the task force, including a separate logistic support group and a tactical air support force. If one battalion was deployed it was probable that the commander of the 3rd Task Force could command both the deployed battalion and the total ODF. But if the entire 3rd Task Force were to be deployed it was considered that he would be fully occupied commanding it, without the additional burden of the total ODF. In that situation it might be necessary for someone else (such as the commander of the 1st Division or Field Force Command) to command the ODF, with its additional responsibilities of administrative support, liaison with other services and the civil community, and responding to the demands of the government and the Department of Defence.

With these concerns, plus the need to develop procedures for the rapid deployment of the task force headquarters and its administrative support, Smethurst gave his battalion commanders a relatively free hand in training their units. During 1980 1 RAR conducted a series of exercises to prepare for the wide range of possible operational circumstances that it might have to face. The need to consolidate and maintain jungle warfare skills partly contributed to the establishment, under Lieutenant Colonel ‘Jungle’ George Mansford, of the 1st Division Tropical Training Centre (later Battle School) at Tully, to teach, exercise and test the ODF battalions in jungle warfare in a tough, combat-like environment.

Throughout 1980 1 RAR was the designated ODF battalion on fourteen days’ notice to move and received priority in men and equipment. But 2/4 RAR, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Ross Bishop, was also part of the ODF and would have to follow closely behind 1 RAR. Whereas 1 RAR was brought up to strength by the posting in of ready-trained infantry soldiers from southern battalions, 2/4 RAR received newly trained recruits from the 1st Recruit Training Battalion and had to conduct initial employment training in the battalion. To their chagrin, the southern battalions had to provide some experienced junior NCOs to help man 2/4 RAR. The battalion’s training was similar to that of 1 RAR, but it was not until about November 1980 that all four rifle companies were fully manned and well trained. On 1 December 1980, 2/4 RAR relieved 1 RAR as the ready reaction battalion.

Troops of 3 Platoon, A Company, 1 RAR training at the Battle School at Tully. The formation of the Operational Deployment Force based on the 3rd Brigade at Townsville, the increased emphasis on training for jungle operations, combined with a reduction in the available jungle training areas around the Land Warfare Centre at Canungra, resulted in the establishment of the 1st Division Tropical Training Centre, later to become the Battle School (photo: 1 RAR).

The most important exercise during 1981 was Kangaroo 81, held in the Shoal-water Bay Training Area in October–November. In one of the largest exercises held in Australia since the Second World War, 20,000 servicemen from three countries deployed under the command of the 1st Division. Along with the 3rd Task Force, the Blue forces included US Marines, US Army units and New Zealanders, and the exercise was therefore the last substantial ANZUS exercise before New Zealand effectively withdrew from the alliance. The 6th Task Force (6 RAR and 8/9RAR) provided the enemy, while the 1st Task Force provided the umpire organisation. The exercise, described officially as training for ‘conventional low-scale mid intensity conflict’, was the culmination of the training of the 1970s, with its emphasis on conventional operations in more open terrain. The deployment of the 3rd Task Force by air and road to the exercise area tested deployment procedures but not the command arrangements for the ODF. The exercise also demonstrated that the 3rd Task Force was severely hampered by its lack of tactical mobility in comparison with the 6th Task Force battalions that at times were mounted in APCs. For the first time since Vietnam in 1965–66, 1 RAR, now commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Barry Caligari, came under the operational control of a US formation.

During the following years the 3rd Brigade (in 1982 the term ‘brigade’ had replaced the term ‘task force’) continued the development of the ready reaction force, and the two battalions refined their techniques for rapid deployment. Unexpected deployment tests and exercises became commonplace. For example, by the time Brigadier Murray Blake was brigade commander in 1983, each battalion had to undergo operational readiness tests involving shooting, physical fitness and deployment tests and a full DP1 administrative check at the Townsville airport. Within each battalion there were constant checks to ensure that the stand-by companies were ready for action. Sometimes there was a brigade operational readiness check involving activities such as a quick deployment of both battalions to attack an enemy position.

The formal brigade deployment exercises, known as Exercise Swift Eagle, were conducted each year with the battalions deploying by air to isolated airfields in northern Queensland. For example, in May 1982 with fourteen days’ notice 1 RAR, with a small tactical headquarters from the 3rd Brigade (Brigadier John Deighton), was deployed by Hercules to an old Second World War airstrip at Macrossan, near Charters Towers. Caribous and helicopters then redeployed the battalion group to the High Range Training Area. A team from Field Force Command evaluated the exercise. Then the money for exercises dried up, and for the remainder of the year all activity was restricted to within 100 kilometres of Lavarack Barracks.11 The first major exercise to test the deployability of the brigade over long distances was Exercise Kangaroo 83, held in the Pilbara area of Western Australia in September–October 1983. The exercise was designed to test the ability of the ADF to react quickly to a low level conflict and to operate in an environment that would be demanding of the men and equipment involved, and in an area distant from the main sources of supply and infrastructure support. The army units involved included the 3rd Brigade, three Army Reserve units, elements of the SAS Regiment, and two regional force surveillance units: NORFORCE and the 5th Independent Rifle Company. The enemy was provided by 1 RAR. Using hired commercial vehicles the troops acted as insurgents, conducting raids and harassment across the Pilbara, but trying to avoid contact with the ADF elements deployed to deal with them. The ODF, comprising 2/4 RAR (Lieutenant Colonel Mike Keating) and the headquarters of 3rd Brigade, was deployed from Townsville to support the Army Reserve and local security forces in the area. The commanding officer of 1 RAR, Lieutenant Colonel Peter Cosgrove, thought that it was the best exercise he had been involved in during his service, in that it related directly to roles and tasks that they might have to cope with in real life; but he was the enemy commander and most of the Blue Force found it fairly dull.12

The ODF procedures were tested further in Exercise Kangaroo 86, held in the Emerald–Blackwater area of central Queensland in October–November 1986. For the first time the full ODF was deployed, and elements of Land Headquarters were deployed to command the ODF, which comprised 3rd Brigade (two battalions, artillery, engineers, aviation and logistic units), a tactical air support force (seventeen utility helicopters, six medium helicopters, six Caribou aircraft), and the 1st Logistic Support Group (1000 personnel). In addition there was an SAS squadron, an Army Reserve battalion, a squadron of APCs, an electronic warfare squadron, and transport resources from the three services. The exercise scenario was based on insurgents disrupting the export of coal from the Bowen basin.

Kangaroo 86 was the culmination of six years of training for the ODF battalions in Townsville, and showed that they had reached a high state of readiness. They were close to full strength, and as mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, within six months of Kangaroo 86 a company group of 1 RAR was deployed on Operation Morrisdance.

The lessons of Morrisdance were absorbed, and in May 1988 2/4 RAR was placed on stand-by to be part of a force to be deployed to Vanuatu if, as a result of civil disturbances, the lives of Australian citizens were in danger. As part of Operation Sailcloth, at 10.15 pm on 19 May the commanding officer of 2/4 RAR, Lieutenant Colonel Ian Ballantyne, was directed to have A Company on two hours’ notice, and the remainder of the battalion on four hours’ notice with effect from midnight. The force was not required, but it was an excellent test of ODF procedures.13

The rapid deployment to the Fiji area in May 1987 and the alert of May 1988 justified both the decision to raise an ODF, and the government’s allocation of resources to bring the ODF battalions to war establishment. But while the government had endorsed the army’s plan for specialised task forces (brigades), the provision of resources for the mechanised brigade in Sydney was not automatic.

The mechanised trial in 5/7 RAR in 1977–78 had shown that an infantry battalion mounted in APCs could never be a substitute for a fully trained and integrated mechanised battalion, but due to resource constraints since that time the battalion had been able to maintain only one mechanised company on rotation. While the army staff in Canberra mounted the case for additional resources, the 1st Brigade at Holsworthy was considering how best to develop the required expertise. At that time 5/7 RAR, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Geoff Skardon, had only one mechanised company, and using APCs from the 2nd Military District pool, could mount another company in APCs. Brigade headquarters had four armoured command vehicles. The problem was exacerbated by the fact that the 1st Armoured Regiment, with which the mechanised battalion had to operate, was located at Puckapunyal in Victoria.

The 1st Brigade had little opportunity to develop new concepts before Exercise Drought Master in the Bourke region of New South Wales in October 1980. Held over a large area, the exercise involved a tactical crossing of the Darling River. Although 5/7 RAR was mounted in APCs, 3 RAR (Lieutenant Colonel Stan Krasnoff ) spent much of the exercise on foot. The mechanisation decision tended to leave 3 RAR out in the cold. While it was appreciated that 3 RAR might not be given a full complement of APCs, there was talk of it becoming a motorised battalion. By the time of Drought Master, Krasnoff was considering the possible commitment of 3 RAR as a heliborne/airborne force in a short term contingency. In December 1980, however, the Commander 1st Task Force, Brigadier Wally Campbell, cautioned Krasnoff that the proposal to train 3 RAR for parachute operations had not progressed beyond the stage of an initial staff study, and that there would be little progress with this capability until after 3 RAR moved to Holsworthy at the end of 1981.14

The movement of families began in September 1981, and continued for the next four months. There was a small, but moving farewell parade at Kapyong Lines on 4 December 1981, and the battalion closed officially at Woodside on 29 January 1982, opening the next day at Holsworthy. The battalion moved into the Finschhafen Lines previously occupied by 8/12th Medium Regiment, and renamed them Kapyong Lines. The construction of the new 8/12th Medium Regiment lines was delayed and for a while accommodation was so crowded that some soldiers lived in tents. Some long-serving 3 RAR soldiers, particularly those with families, chose to remain in Adelaide, and the new single soldiers in the battalion put an additional strain on the live-in accommodation. About 200 families moved to Sydney.

Lieutenant Colonel Peter Arnison, who took command of 5/7 RAR in early 1981, approached the task of mechanisation enthusiastically, but resources were extremely limited and unrealistic expectations were building up, not only in 5/7 RAR, but in the whole brigade. Early in 1982, 1st Armoured Regiment was placed under command of the 1st Brigade (Brigadier John Sheldrick), which started to develop concepts for the command and control of mechanised operations. The army, however, had still not gained approval for the capability.

By early 1983 the CGS, Lieutenant General Phillip Bennett, had won the battle to develop a mechanised capability based on the 1st Brigade. The capability was to be developed in three phases. The first phase was to begin in July 1983 when 5/7 RAR was to be issued with additional APCs and personnel to allow training up to unit level. It was expected that by mid-1984 another company and battalion headquarters would be mechanised. In the second phase additional personnel and APCs would be provided to Headquarters 1st Brigade and some combat support units to allow training, with 1 Armoured Regiment, at up to formation level. The third phase would involve the mechanisation of other combat support and logistic units.15

Lieutenant Colonel Peter McGuiness, who took command of 5/7 RAR in January 1983, had been battalion second-in-command during part of the mechanisation trial in the 1970s, and had the task of expanding the mechanisation capability. When he assumed command, 5/7 RAR had an authorised strength of 25 armoured fighting vehicles (AFVs). After full mechanisation it was planned that the battalion would have 79 AFVs. However, the first step was the mechanisation of another company and battalion headquarters, and in July the new vehicles began to arrive in the battalion transport compound. Battalion training began, with the emphasis on the development of the many skills needed to maintain the vehicles and conduct mechanised operations. Many soldiers seemed to be perpetually on courses.16

It was not possible for the 1st Brigade to conduct brigade exercises during 1983 or 1984, but companies of 5/7 RAR visited Puckapunyal throughout the period, and each year the whole of battalion exercised on the Puckapunyal range. Infantry soldiers learned to care for their vehicles and to think quickly on the move, but still had to maintain the normal battalion commitments, such as providing a rifle company for Butterworth. One company exercised with a British mechanised company in Germany. By this time 5/7 RAR was developing in a different way to the rest of the regiment, and NCOs posted out were likely to return because of their mechanisation training. In barracks soldiers usually wore rifle green berets, and in the field tended to wear ‘baseball’ style caps, or peaked ‘kepis’ rather than the bush hat.17 It was not just a matter of berets and baseball caps. Lieutenant Colonel John James, commanding officer in 1987 and 1988, set out to develop a philosophy of battle group manoeuvre that suited the Australian environment and equipment.

I had to get it into the minds of all NCOs and officers that mechanisation was not simply the conducting of standard infantry tactics at a faster rate—we had gone from fighting for ground to beat the enemy, to using ground to outmanoeuvre and destroy him! To this end the battalion embraced the philosophy of ‘directive control’ well before it became understood (if it has yet been) by the remainder of the Army.

James also emphasised that his battalion had far more firepower than the other battalions. As a consequence of his constant reminders to the battalion that they were the most powerful, quickest reacting and hardest hitting battalion in the army, a unit T-shirt was developed; along with a tiger’s head it stated simply, ‘199 machine guns can’t be wrong’.18

Although mechanisation was not to be a priority for the army, by the beginning of 1986 the Infantry Information Letter noted that 5/7 RAR was ‘now fully mechanised and capable of conducting mechanised operations in conjunction with armoured units’, and the battalion title was changed to 5/7th Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (Mechanised), or in its abreviated form, 5/7 RAR (Mech). At that time the battalion was equipped with 3 ACVs, 56 APCs, 4 APC(M)s, 4 APC(F)s, an armoured recovery vehicle and 7 TLCs. By 1989 the battalion had one rifle company designated each year as the supporting mechanised infantry subunit which regrouped under command of the 1st Armoured Regiment as required. Also, 5/7 RAR received a squadron of tanks on the same basis. This arrangement, together with the allotment of the 101st Medium Battery as direct support battery and the provision of a mechanised engineer troop from the 1st Field Squadron enabled the battalion to exercise regularly in a battle group setting. Early in 1988 the battalion assumed responsibility for anti-armoured skills, following the transfer of the Milan anti-tank weapons from B Squadron, 3/4th Cavalry Regiment.19

When the reorganisation of the 1st Division had first been discussed by the CGS Advisory Committee in June 1979 it had been proposed to develop a limited parachute capability in the 6th Task Force, as it was realised that there was a need for a force to secure remote airstrips, such as on Christmas Island, if the government wished to move a larger force there. But when General Dunstan had put his proposal to the government in late 1979 he had not raised the requirement for a parachute capability. Nonetheless, he was in no doubt about the need for a parachute capability; as he explained at the CGS Exercise in 1980, there ‘could be a number of contingencies where we might need to use an airborne force, the most likely being to secure an airfield through which to deploy the ODF’. He added that ‘a useful byproduct of an airborne unit would be as a recruiting ground for the SAS Regiment’, which was expanding to meet counter-terrorist commitments.20

It will be recalled that in 1974 6 RAR had formed an airborne company, and although that capability had not been maintained, it seemed logical to continue the training in that battalion. Consequently, in 1980 6 RAR was given the task of developing the doctrine for the deployment of a parachute company group, and since Major David Christie was a parachute jump instructor, the role was allocated to D Company, which he commanded. Later that year 6 RAR conducted Exercise Dusty Canyon in the Katherine–Tindal area of the Northern Territory to examine the operational and logistic problems associated with independent unit operations, and D Company conducted its first parachute deployment.21

The first full-scale parachute exercise, Exercise Distant Bridge, was conducted in April 1981. Led by the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Mattay, D Company and attached troops flew 1500 kilometres from Amberley to Tasmania in four C–130 aircraft and 162 parachutists descended at first light onto an old Second World War airfield at Ross. The company group then covered 80 kilometres by foot to secure an area. Some weeks earlier the Minister for Defence, James Killen, had said that the introduction of airborne operations in the army was part of the ‘requirement to develop a versatile and mobile land force with the capabilities and preparedness needed for the defence of Australia’.22 The lessons from Distant Bridge provided a firm basis for continuing development, which was tested both in Exercise Kangaroo 81 in October 1981 and early in 1982 when the company group successfully took part in Exercise Bounty Hunter in northern New South Wales.

However, as described earlier, by late 1980 there was talk of developing a parachute capability in 3 RAR. Brigadier Sheldrick was quick to remind 3 RAR that the concept, which was yet to be agreed, was that 3 RAR would remain as a normal infantry battalion but with a parachute capability. It was intended that D Company, 6 RAR would retain their parachute capability and would be available to 3 RAR should a four-company battalion deployment be necessary.23 Plans for a parachute capability began to solidify during 1981, and at the end of the year Dunstan directed that studies be undertaken to develop not just a parachute-capable battalion, but a full parachute or airborne battalion.24

Although 6 RAR had developed and maintained a parachute company group against considerable difficulties, there were advantages in giving this role to 3 RAR. Once it was based in Holsworthy it would be close to both the RAAF tactical transport squadron at Richmond air force base and the Parachute Training School at Williamtown. But perhaps more importantly, it seemed that there would never be sufficient resources for 3 RAR to be mechanised, and if the battalion did not have a clear role it could possibly be disbanded. Although 6 RAR fought a tough rearguard action to retain the capability, 3 RAR had support in Canberra.

Meanwhile, during 1981, 3 RAR had begun sending soldiers for training at the Parachute Training School. Lieutenant Colonel Jim Connolly, who had been nominated to take command of 3 RAR early in 1982, decided that ‘the best way to concentrate the attention of the battalion and maintain its spirit at a time of instability and movement was to focus on the parachute role’. In mid-1981 he discussed this approach with the CGS, General Dunstan, who did not demur.25 By June 1982, 80 soldiers from 3 RAR, led by Connolly and the RSM, WO1 M. Martin, were able to conduct parachute continuation training at Richmond.26

Throughout 1982 the army staff in Canberra worked to justify an airborne battalion, discovering that there was little difference in the resources needed to move from a parachute-capable battalion to a fully airborne battalion. Army staff argued that in both mid and low level conflicts the minimum requirement was an airborne battalion with artillery, engineers, communications and logistic support, and since the resources required could be covered within the extant finances, the capability was approved. On 29 June 1983, both 3 RAR and 6 RAR were officially informed that from 31 December 1983 the requirement to provide a parachute capability for the ADF would pass from 6 RAR to 3 RAR. It was planned that during the 1983/84 financial year 3 RAR would form a parachute company group with its allocation of engineer and signal support. In the following financial year 3 RAR was to form another parachute company, and by 30 June 1987 the battalion was to have a third company trained.27

By the end of 1983 the battalion, from October officially titled a ‘Parachute Infantry Battalion’, had approximately 290 trained paratroopers, plus a number of specialists (PJI, SLD, freefall), and over 3200 descents had been conducted by 3 RAR personnel. As the editor of the battalion magazine, Kapyong Kronicle, wrote, ‘It clearly demonstrates what a unit can do by driving a concept from below rather than waiting for the uncertainty above to clear.’28

Under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Kerry Gallagher, 3 RAR further developed its parachute capability during the next two years. On 16 April 1985, for the first time since Nadzab in 1943, a conventional Australian military force parachuted onto foreign soil when a company group flew direct from Richmond to the North Island of New Zealand. Perhaps the most significant event of 1985, however, was the decision to issue all para-trained members with the cherry coloured wings previously worn by the 1st Australian Parachute Battalion in the Second World War, and the battalion was authorised to wear the ‘dull cherry beret’. By the end of the year over 400 soldiers were para-qualified.

While 3 RAR was forging ahead with its own concepts, army planners in Canberra were still developing a role for the battalion to support the ODF. From the beginning it had been realised that the ODF would require the support of a third battalion and in July 1986 the CGSAC agreed that 3 RAR should be able to provide ‘point of entry security for an ADF group operationally deployed in response to shorter term contingencies’ and would also ‘provide a third battalion for augmentation of the ODF brigade’.29 The battalion group was to be on 28 days’ notice to move with a company on shorter notice. As an official ODF augmentation unit 3 RAR could therefore expect an increased priority in the allocation of resources.

With this additional direction 3 RAR was now able to focus more clearly on possible roles, and these were spelt out by the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Peter Abigail, in his training directive for 1987. The battalion’s primary objectives were: first, to maintain the capability to deploy by parachute, with limited supporting arms elements, to secure a point of entry for the ODF or other elements of the division; second, to develop the capability to conduct ‘crash action’ independent operations to destroy concentrated enemy groups, including groups in an offshore territory; and third, to provide the third manoeuvre element for the 3rd Brigade if required. It was likely that the battalion group would include A Battery, 8/12th Medium Regiment (air-landed), 2 Troop, 1st Field Squadron, a signals detachment from HQ Squadron, 1st Brigade, a detachment from 176 Air Despatch Squadron, 39 Air Delivery Equipment Maintenance Platoon (personnel parachute packers) and 1st Parachute Surgical Team from the 1st Field Hospital.30

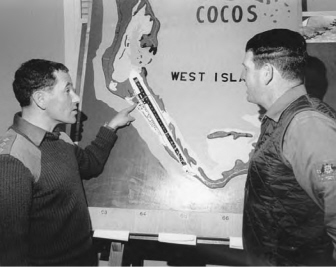

In August 1986, a company group from 3 RAR parachuted into Cocos Island in the Indian Ocean. The photograph shows the adjutant, Captain Steele Brown, and the RSM, WO1 Colin Lee, during the planning phase of the exercise (photo: 2 MD PR SYDA/86/232/11).

These modified roles had already been tested by two major exercises. First, in August 1986, a company group had carried out a long range insertion into Cocos Island to test the battalion’s role in independent operations and to demonstrate that Australia had the capability of exercising sovereignty over its remote territories. The second exercise, Exercise Far Canopy, was held at Shoalwater Bay in September 1986 and practised the battalion in seizing a point of entry for other elements of the ADF.31

Although 3 RAR was not involved in Operation Morrisdance in May 1987, the battalion’s value as a ready reaction force was confirmed in May 1988 when a company group was placed on stand-by for Operation Sailcloth. With a crucial role in the ODF’s deployment plans 3 RAR’s future as a parachute battalion seemed assured.

This development was confirmed on Exercise Far Canopy 89 in June 1989, when the 3 RAR battalion group, commanded by the airborne force commander, Brigadier Frank Hickling (Commander 1st Brigade), launched at short notice from RAAF Richmond and parachuted directly onto the airfield at Nowra. The battalion secured the airfield, accepted a ten-sortie heavy drop and air-landed the guns from A Battery and other stores, while conducting an evacuation of ‘Australian nationals’, proving that a sizeable force on light scales could deploy at short notice over considerable distance.32

It will be recalled that under the 1980 reorganisation plan 6th Brigade in Brisbane was to continue training as a standard infantry formation, concentrating primarily on training for open country warfare, with the aim of being prepared to reinforce 3rd Brigade. Its secondary objectives were to develop capabilities for operating with ships of the navy’s amphibious squadron, and in built-up areas (military operations in urban terrain or MOUT).33

During the 1980s both 6 RAR and 8/9 RAR followed somewhat similar training patterns. Generally each year the battalions’ field training began with section level activities and built up to sub-unit and unit level exercises. In addition, each year the brigade conducted Exercise Diamond Dollar, usually in the Shoalwater Bay Training Area, designed to exercise the brigade in open warfare, usually with the assistance of a squadron of tanks from 1 Armoured Regiment. Diamond Dollar also enabled the battalions to exercise sea transport by sailing from Brisbane to Shoalwater Bay in HMAS Tobruk or in the landing craft of the RAN Amphibious Squadron based at HMAS Moreton in Brisbane. In late 1985 the Amphibious Squadron was mothballed and Tobruk was relocated to Sydney, thus making joint exercises less frequent.

Both battalions acted as enemy during Kangaroo 81 in October 1981, and both were heavily involved with the Brisbane Commonwealth Games in September and October the following year. While 8/9 RAR provided the Royal Guard for Her Majesty the Queen at the opening ceremony, 6 RAR provided the ceremonial flag party for the opening and closing ceremonies.

Overseas exchanges became a feature of the training for not only the Brisbane battalions but for all the battalions of the regiment. Every eighteen months each battalion was required to send a rifle company group for three months’ duty at Butterworth in Malaysia. In addition, there was a company exchange with the 25th US Infantry Division in Hawaii; for example, D Company, 6 RAR visited Hawaii in both 1980 and 1985. In July 1981, a company of Gurkhas from Hong Kong arrived in 6 RAR for six weeks’ training with the battalion. In 1985 the exchange became reciprocal, and in July 1987 A Company, 6 RAR changed places with B Company, 10th Gurkha Rifles in Hong Kong. Various battalion headquarters were routinely involved in Exercise Tropic Lightning in Hawaii, the annual command post exercise conducted by the 25th US Infantry Division. From 1983 company groups from the Royal Thai Army began to visit the Brisbane battalions, and in March–April 1989 for the first time an Australian company, C Company, 3 RAR, exercised in Thailand. During 1982 Major Tony Casey and Sergeant Peter Orth of 8/9 RAR spent six months in Uganda developing and conducting the first courses for officers and SNCOs at the Uganda Infantry Centre under the control of the multinational Commonwealth Training Team Uganda, and they were replaced by WO Gary Hunter and Sergeant Rod Smith, also of 8/9 RAR.

Perhaps the biggest test was Exercise Caltrop Force, held in California in April 1989. Apart from providing a unique opportunity for training in a combined operations setting with allies, this was the first large scale validation of ABCA (America, Britain, Canada, Australia) operating procedures and standardisation agreements held outside Australia, and involved battalions from the four ABCA countries. Australia was represented by 6 RAR, the first time an Australian battalion had deployed overseas since 6 RAR had served as part of the ANZUK Brigade in 1973. It was a new-look Australian battalion with disruptive pattern uniforms and the recently issued 5.56 F88 Steyr individual weapon. The MAG 58 had also replaced the interim L7 as the section machine-gun.

The ultimate purpose in this training was to contribute to the defence of

Lieutenant Colonel David Mead at the beach landing of 6 RAR during Exercise Caltrop Force in California in April 1989. Behind Mead are three Marine AAVP7s. Notice the Miles laser projector on the rifles and the laser sensors on the helmets and torso harnesses to enable firers to register hits against the targets. The equipment was on loan from the US Army (photo: 6 RAR).

Australia, and this was given focus by the Dibb Review of 1986 and the subsequent Defence White Paper of 1987. As a result, all the battalions were deemed to be an essential part of the ADF and 6 and 8/9 RAR received more attention than earlier in the decade. These battalions were seen as ‘follow-on’ battalions for the ODF and accordingly were given enhanced readiness status. To facilitate this mission 49 RQR joined the two regular battalions as the third battalion of an integrated regular– reserve 6th Brigade.

A key exercise in developing concepts for low level conflict was Diamond Dollar in October 1987. Held on Cape York peninsula, the exercise involved the deployment of Headquarters, 1st Division and 6th Brigade (6 and 8/9 RAR) with both 1 RAR and 3 RAR as enemy. The exercise was good preparation for Kangaroo 89, conducted across the north of Australia from the Pilbara to Cape York peninsula in August 1989, and involving all six battalions of the regiment. The exercise was designed to test the concepts espoused in the government’s 1987 White Paper and the new command and control arrangement for the ADF.

The 1980s saw increased emphasis on military competitions, both within the regiment and with other armies, and the Duke of Gloucester Cup, for example, was keenly contested by the battalions.34 The victory of 1 RAR in 1986 gave it the right to represent the regiment in the Cambrian Patrol Competition, an arduous military skills competition run by the British Army in Wales. It is open to all regiments and corps of the British Army and also some foreign armies. The 1 RAR team comprised the victorious Gloucester Cup team, led by Corporal R.A. Modystack, plus Lieutenant A.D. Blumer, WO2 J.R. Sheehan and Sergeant B.F.H. Vandenhurk (a later RSM of the regiment). Despite unfamiliar NATO procedures and British equipment, 1 RAR won. The British Army changed the competition format for subsequent years. In 1987 Corporal M.F. Conlon’s section from 1 RAR represented Australia and in appalling weather won a Silver Medal, while Corporal Wischusen’s section from 3 RAR won a Bronze Medal in 1988, the last year Australia competed.35

As the regiment approached the 1990s its battalions were considerably different from those that had first been raised in the aftermath of the Second World War.They had now experienced almost twenty years of peace. When Lieutenant Colonel Mike Smith assumed command of 2/4 RAR on 9 December 1988 he became the first commanding officer of a regular Australian infantry battalion not to have seen active service. He had graduated from Duntroon in 1971 and had been a United Nations observer in Kashmir. The other commanding officers in 1989 reflected the changing nature of the regiment. John Petrie (1 RAR) had served as an SAS soldier in Vietnam before attending Portsea. Simon Willis (3 RAR) had graduated from Duntroon in 1970 and had served as a platoon commander in Vietnam in 1971. Rod Margetts (5/7 RAR) was a national serviceman who had served with the AATTV in 1972. David Mead (6 RAR) was a direct-entry pilot and Scheyville graduate who had commanded a platoon in Vietnam in 1969 until seriously wounded in a mine incident and who returned to Vietnam in 1971–72 with the AATTV. Gary McKay (8/9 RAR) was a national serviceman who had been wounded and awarded a Military Cross while commanding a platoon in Vietnam in 1971. When Willis and Mead finished their tours in command at the end of 1989 they were succeeded by Duntroon graduates who had been too young for service in Vietnam.

There were similar changes in the ranks of the senior NCOs. For example, in 1988, only six of the 36 company sergeant majors in the regiment had seen active service. Nevertheless, all the RSMs in 1989 had had at least one tour of duty in Vietnam.

From the earliest days the higher direction of the regiment had been divided between Regimental Headquarters, at the Directorate of Infantry in Canberra, and the Infantry Centre, located since 1972 at Singleton, New South Wales. Through the Depot Company (RAR) the Infantry Centre provided the indoctrination and infantry training for the soldiers who had completed recruit training at Kapooka, while the Infantry School provided higher level specialist training. Regimental Headquarters in Canberra was well placed to argue the regiment’s cause in the corridors of power; but the Director of Infantry, as Regimental Colonel, was not ideally located to plant his own personality on the development of the regiment. The argument for collocating Regimental Headquarters and the Infantry Centre was never compelling, but in 1989, to reduce the number of higher ranking officers in Canberra, the CGS relocated the Director of Infantry to Singleton. In December 1989, Colonel Peter Cosgrove became the first Regimental Colonel to be located at the Infantry Centre, which for the first time, in all respects, became the regimental base. Cosgrove had the dual roles of Head of Corps/Regimental Colonel and Commandant of the Infantry Centre. This was a significant development, with the expectation that there would be increased cohesion and direction within the regiment.

By 1990 the regiment’s battalions were considerably different from those a decade earlier. Not only had the battalions retained their regimental standards, traditions and ethos, their soldiers were fitter, better trained, better equipped and more versatile than they ever had been. The officers were more politically aware and had a better grasp of defence policy and the general purpose of the ADF. But the officers and men had also been put under additional strain by an increasing divergence between attitudes in society and the standards that are essential for success in battle. The battalions were training more frequently in the remote areas of northern Australia, and overseas training was being conducted on a regular basis in Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, Hawaii and Hong Kong. Nonetheless, at the end of the decade, active service overseas seemed almost as remote as it had been ten years earlier. The deployment of 1 RAR during the 1987 Fiji crisis, however, was a hint of things to come. The next decade was to bring more upheaval, and uncertainty; and significantly, it was to find the battalions once more on active service.