14

Upheaval, Uncertainty and Opportunity

UN Operations and Australia, 1990–99

Craig Stockings

During the 1990s three fundamental forces shaped the Royal Australian Regiment. First, a string of official policy papers and reviews confirmed a new strategic agenda for the army. Second, an incessant search for ‘efficiency’, necessitated by restricted government spending, influenced defence decision making. Third, the deployment of formed bodies of infantrymen on operational service for the first time since 1972 had a significant impact on the regiment. Through the course of the decade these three factors had considerable implications for force structuring, equipment procurement and training. The 1990s was a difficult period for the regiment, but as a consequence of the disruption and transformation forced upon it, it emerged a more vigorous, focused and potent organisation than it had been since Vietnam.

Strategic Direction and Cost-cutting

Evolving strategic imperatives had a marked influence on the development of the RAR throughout the 1990s. Due to the ideas espoused in the 1987 Defence White Paper, The Defence of Australia, for most of the decade the army was guided by the principles of self-reliance, the defence of northern Australia and the absence of any foreseeable conventional threat. Importantly, the application of these principles changed the training and preparedness orientation of the regiment’s battalions from an ‘expansion-base model’ to ‘one better suited to low-intensity conflict’.1 The ability to react to and repel small-scale incursions now took primacy of place. A ‘terminal force’ model whereby the army was expected to engage and defeat an enemy without relying on pre-operational expansion replaced the ‘core force’ concept, in place since 1976.2 The focus on low-intensity conflict was derived from an assessment of likely regional risks, capabilities and credible ‘raid-type’ contingencies rather than a vague and unlikely full-scale invasion.3

Reflecting this shift there followed a series of strategic reviews based upon the idea that the key role was defending northern Australia from low-level incursions. The 1994 White Paper called for a re-examination of combat force structures and the army’s resultant report, The Army in the Twenty-First Century (Army 21), was presented in 1996. Of central importance to the regiment, Army 21 sought to examine ‘the number and readiness of infantry units . . . the balance between Regular and Reserve elements and the resource implications required for future change’.4 The government response to this review was the Restructuring the Australian Army (RTA) initiative. In launching the RTA program the Minister for Defence, Ian McLachlan, noted that ‘elements of the force are hollow’ and that current army structures were ‘inadequate to meet the demands of widespread concurrent operations’.5 For the regiment this heralded a range of significant and far-reaching structural reforms.

Despite the changes, however, the RTA left the regiment poorly placed, in terms of training, equipment and structure, for another late 1990s shift in strategic orientation. A new White Paper, Australia’s Strategic Policy 1997, shifted the focus from the defence of northern Australia towards one that emphasised engagement in the Asia-Pacific region. Importantly for the regiment, preparedness and readiness levels were, from that time, to be ‘determined more by the requirements of regional operations . . . than by the needs of defeating attacks on Australia’.6 A decade of reasonably firm strategic guidance, first concentrating on defending the north, followed by a late transition to regionalism, was an important and enduring influence on the development of the RAR.

As always, government spending also had its impact. With falling government expenditure on defence as a whole, the army made concerted and repeated efforts to cut costs. Such internal parsimony was necessary, as in an era of continental and maritime strategies the army found it more difficult to define its role than the other services, and subsequently bore the brunt of cutbacks.7 In 1989 Alan Wrigley was commissioned to report on how money might be saved by better integrating civilians into the Defence Force with the resultant funds to be spent on equipment modernisation and combat training. His June 1990 report advocated the commercialisation of non-combat duties, a reorganisation of the Army Reserve, and self-sufficiency; all of which had significant implications for the regiment.8 In one key argument, for example, Wrigley contended that regular forces would be unable to sustain operations for any length of time and, in order to save money, proposed to reduce their number by around one-third while doubling the number of reservists.9

The Wrigley Report was followed in May 1991 by the Force Structure Review, which again sought to increase combat effectiveness by shifting funds from non-combat activities. In reality, however, it became an exercise in slashing the army’s regular establishment.10 The search for savings continued throughout the decade. In October 1996, in order to secure departmental funding and as a means to finance the RTA initiatives, McLachlan instituted the Defence Efficiency Review.11 The report, in its recommendations to contract out non-core army business to civil agencies, was in many ways an extension of Wrigley’s proposals.12 The effort to ‘cut the tail to strengthen the teeth’ achieved little more than further reductions to regular numbers, which now stood at 23,000.13 Subsequent discontent saw, by the end of 1998, some 20 per cent of regular lieutenant colonels submit their resignations.14

Cost-cutting and shifts in strategic guidance, however, were but two of the three forces that guided the development of the regiment. The third concerned a series of operational UN deployments.

UN Deployments—Somalia, Cambodia and Rwanda

Before and throughout the 1990s individual Australian infantrymen had served in a range of peacekeeping missions in the Sinai, the Balkans, Western Sahara and Bougainville. What was new for the regiment in this period, however, was the operational deployment of formed infantry units and sub-units for the first time since Vietnam, the first of which was to the troubled east African nation of Somalia.

On 15 December 1992, the government announced an Australian contribution to the US-led, UN-sanctioned Operation Restore Hope in Somalia. In the wake of civil war the country was suffering from famine and sectarian strife with rival ‘warlord’ gangs terrorising the population in an effort to control the flow of food and humanitarian aid provided by the UN and international non-government organisations (NGOs).15 At first the UN sought to alleviate suffering by providing protection for NGOs distributing food and other essentials (United Nations Operation in Somalia—UNOSOM 1). The deteriorating security situation soon necessitated a more powerful response, however, and in late 1992 the US was authorised to lead a coalition to protect the aid effort and enforce peace if necessary. It was as part of this Unified Task Force (UNITAF) that an Australian Army contingent was committed under Operation Solace.16 The contribution consisted of a national headquarters in Mogadishu, the coastal capital of Somalia, and a battalion group of 653 personnel based on 1 RAR (including 52 soldiers from 2/4 RAR).17 The deployment was restricted ‘on political grounds’ in terms of size, cost ($17 million), and time (seventeen weeks).18 Two factors helped tip the government’s hand in favour of deploying an infantry battalion. First was a security situation that warranted a capable combat force. Second was a feeling within the army that the ODF needed to be deployed, after such a long absence from operational service, for ‘morale and readiness reasons’.19

Lieutenant Colonel David Hurley, commanding 1 RAR, received formal warning for Operation Solace in mid-December 1992. While the battalion was geared to react quickly, it was an inopportune time as most of the unit had commenced its annual stand-down.20 Being so close to Christmas, Hurley decided to modify existing procedures by initially recalling only the online company, A Company, and elements of BHQ while leaving the remainder of the unit on leave.21 The spirit surrounding the upcoming operation was well captured by Private Manvell Newton who recalled: ‘I was very excited at first, I was going to be able to do my job and a lot of attention was focused on us at the time before we went and when we went. So I was very eager to go over.’22

Major Doug Fraser’s A Company embarked in HMAS Jervis Bay on 24 December without any clear idea of their mission or the rules of engagement (ROE). Hurley conceded that the company was left ‘pretty much high and dry’ and that, at this stage, even he had ‘not much idea of what we were going to be required to do’.23

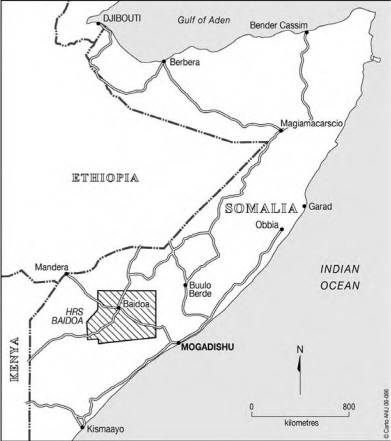

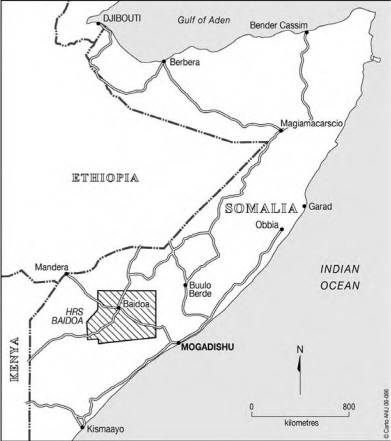

MAP 10: 1 RAR Area of Operations in Somalia. From 19 January 1993 the 1 RAR Battalion Group took responsibility from the US Marines for the Humanitarian Relief Sector (HRS) established around the township of Baidoa. Within the HRS the battalion group oversaw the delivery of over 8000 tonnes of aid to 137 villages, and through an active program of foot, battalion vehicle and APC patrols, exercised its control of the area until returning to Australia in May 1993.

Meanwhile, at Lavarack Barracks the rest of 1 RAR was busy with pre-deployment orders, rehearsals, inoculations, weapons preparation, intelligence briefings, skills revision and the issuing of additional equipment. Scenario-based playlets in which individuals had to react to varying ‘peacekeeping’ situations were used as a tool to prepare soldiers for their likely tasks.24Jervis Bay and A Company arrived offshore from Mogadishu on 12 January 1993. The commanding officer and his advance party departed Australia on 8 January and the main body followed in two groups, one each on 15 and 18 January.25

In Mogadishu 1 RAR came under the operational control of the US 10th Mountain Division, much the same way it had come under the control of the US 173rd Airborne Brigade when deployed to South Vietnam in 1965. After a night in transit lines, BHQ and A Company flew into the battalion’s area of operations with the remainder of the unit following over the next three days. The battalion group was given responsibility for a Humanitarian Relief Sector (HRS) in the southwest of the country and tasked with providing security, protecting humanitarian operations, and promoting the establishment of a functional civil infrastructure.26 In many ways the area bore a physical resemblance to parts of northern Australia, except for the ubiquitous camel bushes, the thorns of which had ‘incredible strength in piercing tyres, flak jackets and legs’.27 Baidoa, nicknamed the ‘City of Death’ thanks to the 30,000 shallow burials in and near the town, and nestled in a ‘dry dusty sea of red dirt’, was the most established town in the area with a population of 60,000 to 80,000 people including refugees.28 After a quick handover with 3/9th Battalion, US Marine Corps, the 1 RAR group took responsibility for the HRS on 19 January.29

The scene that greeted the battalion in Baidoa was one of almost complete devastation. Public and government buildings were gutted, wreckage littered the streets and there was no electricity. Few locals ventured out of doors in daylight and fewer still at night. Lieutenant Colonel Hurley remembered the scene as resembling ‘a big garbage dump’ with refugees ‘living under piles of rubbish, twigs and grass interlaced over the top of plastic bags, cardboard over the top, whatever they could get their hands on’.30 The first priority was to secure the Baidoa airfield, selected as the battalion group’s firm base location, which had been fortified by a series of strong points and observation posts with wire strung around the perimeter to delineate it as a military compound. Accommodation there consisted primarily of canvas tents with BHQ initially in a roofless building close to the runway with tarps stretched over the walls for shade.31 A lingering memory of airfield life for the adjutant, Captain G. Babington, was the latrines that, filled with an oil/diesel mix, ‘were burnt every morning but never smelled like victory’.32 Although the observation posts gave a good visual coverage, ‘given the way the Somalis could penetrate the wire fairly quickly’, it was never truly ‘secure’.33

The battalion group’s mission, to ‘provide a secure environment for the distribution of humanitarian relief aid in the HRS’, was not an easy proposition given the 17,000-square-kilometre sector and the desperate need of the locals. Lieutenant Colonel Hurley’s plan consisted of four key assignments through which the rifle companies rotated every seven to ten days. These tasks were to protect the Baidoa airfield, provide security to the township, in-depth patrolling of the HRS, and escorting aid convoys within it.34 Additionally, one platoon in modified 6x6 vehicles was committed to mobile counter-ambush patrols at night.35 Nearly all of these tasks entailed independent platoon and section operations.36

Somalia, March 1993. Corporal Leroy Meulengraff (centre), Lance Corporal Peter Larsen (left) and an unknown soldier, all of D Company, 1 RAR, record the details of weapons confiscated during Operation Restore Hope. Removing weapons from the local community was one of the key activities undertaken by the battalion group in Somalia (AWM photo no. P01735.274).

Three issues complicated the battalion’s four-pronged plan. The first was uncertainty over the loyalty and reaction of the locals. The second was the ROE that precluded the use of mines, ambushing and snipers in their traditional roles. Though unit consensus was that ‘one or two good ambushes could have resolved a lot of problems in the early days’, these rules were not a major constraint and patrols remained free to prosecute and follow up contacts and detain suspects. 37 The third problem was bands of roving gunmen, often in modified vehicles known as ‘technicals’, which plundered and terrorised locals and aid workers.38 On around twenty occasions Australian patrols exchanged fire with them, mainly at close range, resulting in a small number of Somali casualties and one Australian wounded in action. An unpredictable 24-hour patrolling schedule, and aggressive prosecution of contacts, did much to discourage any large-scale action on the part of these bandits.39

To provide security in Baidoa township a foot-patrolling program was quickly established. These were usually around three hours long, conducted by day and night, and supported by a platoon-sized reaction force. Initially they were coordinated by a traditional battalion ‘patrol master’ and conducted from the airfield base. Given the two-kilometre entry/exit routes to the town, however, this method was soon altered so that a ‘patrol company’ was irregularly relocated to an NGO compound in Baidoa. More time was therefore available and an element of uncertainty was introduced into the minds of potential adversaries.40 At the height of unrest in the town two companies were deployed to patrol it. Patrols were exhausting and exhilarating with few passing without some kind of incident. Many patrols soon noticed that in some areas radios, torches and music were used to warn of their approach and with the individual soldier’s burden of helmet, flak jacket and webbing it was not surprising that few offending locals were chased down. Moreover, temperatures were often in excess of 30 degrees by mid-morning and ‘you could feel your concentration being tested after three hours patrolling’.41 There was plenty of variety, however, and patrols in Baidoa were involved in unexploded ordnance incidents (and related accidents), crowd control, searches, preventing extortion at markets, robberies, vehicle accidents and ‘contacts’.42 A number were fired upon at night but often the distance and lack of visibility prevented an engagement. On the first occasion where a section on patrol was able to return fire one bandit was killed and two injured. On another occasion a soldier had his night vision goggles ‘shot out’ while a section-mate found a number of bullet holes in his pants without suffering any injury.43

With the airfield and Baidoa relatively secure a system of ‘in-depth’ patrolling of outlying areas was established. The aim of these dispersed operations was to dominate the villages and areas in the extremities of the HRS with a mind to establishing a presence and rapport with the locals as well as keeping an eye out for weapons and suspicious characters. Such patrols, deployed by APC, truck, or in one case by helicopter at night, often included a cordon and search of a village and it was during these actions that some interesting operational techniques were developed. As the ROE precluded ambushing, for example, sections often laid in wait for suspected bandits and then hit them with intense white light before questioning and searching them.44 Company commanders were almost autonomous during these six- to nine-day tasks and regularly found snipers, reconnaissance, intelligence and liaison teams attached.45 As security around the airfield and Baidoa improved, an increasing number of troops were committed to patrolling in depth.

With the battalion established in Baidoa and various out-stations, enemy action tended to focus on ambushing the Mogadishu road from Bracaba to the HRS boundary.46 Accordingly the protection of aid convoys became important and it was in this way that the battalion most directly supported the humanitarian effort. Food escorts were hectic with Somalis at most distribution sites starving, malnourished and desperate. Villagers regularly rioted when food arrived and sometimes attempted to push through barbed-wire barriers to access it. In many cases a simple and effective food distribution method was used where NGO trucks were backed towards each other to create a corridor blocked at all points but its ends. At the same time Somali men were separated from women, who then had their ration cards stamped before they progressed through the corridor to be issued with food and cooking tools, as nurses checked the health of any babies present.47 Initially, quite large escorts of up to a company size were used, but when the battalion felt more secure, platoons would often ‘look after three or four vehicles, or more at times’.48

Complementing the four basic rotating company tasks were a number of battalion-level cordon and search, sweeps and clearing operations designed to have a psychological effect on the Somalis.49 Similarly, civil affairs operations were conducted on top of other duties including a ‘clean up Baidoa’ campaign, the protection of water supplies, an effort to encourage locals to hand in weapons pillaged from nearby ammunition dumps, and eventually the establishment of a judicial system, a prison and an auxiliary security force. In the last six weeks of the deployment this local force was incorporated into the town patrolling program.50

Operation Solace was a demanding deployment. Apart from a difficult climate and terrain in a primitive and disease-ridden country, the troops lived in crowded and basic conditions with next to no recreational facilities.51 For the first two months the rate of activity was similar to an annual two-week exercise and by mid-March the need to regulate the pace and commence a rest program had become obvious.52 The commanding officer was always cognisant of this fact but, given the time limit of the deployment, concluded that the unit could sustain the high rate of effort.53 In particular, a lot was asked of the battalion’s section and platoon commanders. Hurley reflected:

I’d often give a platoon commander a section of APCs, his platoon and an area of 25 to 30 kilometres square and that was his area to look after. Not only might he have a convoy for a day that he was looking after, but for a week he could own a piece of turf with his own platoon, have sufficient assets to do the job there, and get on with it.54

During the deployment the Somali bandits never seriously challenged 1 RAR. According to Lieutenant J.A. McTavish, commanding 5 Platoon, enemy response to contact was ‘either to withdraw in a disorderly manner with no real attempt at fire and movement, or to drop their weapons and surrender’.55 One more notable action, however, involved a section pinned down by enemy fire during an obstacle crossing at a crossroad in Baidoa. Corporal Bill Perkins asked his forward scout if he could engage with a 66 mm anti-armour weapon but he was within arming distance of the rocket. Perkins then ‘deployed my other 66 from the number one rifleman behind me. I gave the section the order to rapid fire, he stuck his head out and fired the 66 and it went high on the building but it caused the rubble to come down on top of them’.56 The deployment was not without tragedy, however, when on 2 April 1993 Lance Corporal Shannon McAliney was shot and killed by an accidental discharge while on patrol.

Operation Solace effectively ceased on 4 May 1993, the date on which the UNOSOM II mission assumed command of UN activities in Somalia.57 After handing their responsibilities over to a French unit, all Australian troops had returned home by 23 May. The battalion group was generally regarded as one of the most effective of the national contingents deployed under UNITAF. Within its HRS it conducted over 400 convoy escorts to 137 villages distributing around 8000 tonnes of food, seed, clothing and tools. An embryonic law and order system was established which included 250 policemen, regional courts and a prison. Over 70 bandits were arrested and a potentially large maize crop planted. Commerce was commenced and over 900 weapons, ranging from pistols to a 106 mm recoilless rifle, were captured.58 1 RAR’s display of professionalism, compassion and aggression where needed reinforced its commanding officer’s ‘faith in our soldiers and our training’.59

A number of lessons learned by 1 RAR in Somalia influenced the future direction of the regiment and the wider army. Hurley noted after the operation that insufficient urban warfare training was conducted before the deployment with tactics and techniques developed on the run.60 A much greater training focus was subsequently given to this type of operational environment culminating in the construction of a dedicated urban warfare facility at High Range Training Area in Townsville in 1997.61 The lack of integral aviation support was also considered ‘quite limiting’ for both tactical mobility and casualty evacuation.62 Such observations no doubt helped facilitate the establishment of new Black Hawk helicopter squadrons and airmobile doctrine in the early 1990s. During the operation, in urban environments, B Company used a variation of the British ‘brick’ method whereby half platoon patrols were broken down into three four- or five-man ‘bricks’.63 The success of this tactic helped ease the passage of new infantry section ‘fire team’ doctrine. The continued importance of infantry–armour cooperation in low-intensity conflict was illustrated and the presence of APCs was ‘quite overwhelming to the Somalis’.64 Finally, the destructive impact of setting deployment ‘end-dates’ was also noted by military authorities who acknowledged many Somali warlords simply awaited ‘the withdrawal of UNITAF before returning to their inter-factional rivalries’.65

As the soldiers of 1 RAR were returning home a second important operational deployment was taking place, although for the regiment it was on a much smaller scale. In March 1992, the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) was established to monitor a civil war ceasefire and subsequent elections.66 The Australian contribution to UNTAC consisted of a force communications unit (FCU) of over 500 personnel under Operation Gemini. The mission of the FCU was to provide communications between Cambodian factions and from those factions to the UN. From January 1992 5/7 RAR was used to train around 200 FCU personnel, of which 54 were drawn from the unit’s Support Company. The commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Peter Pedersen, described the deployment as 5/7 RAR’s ‘biggest operational contribution for almost 20 years’.67 Individual soldiers were also drawn from the other battalions of the regiment. All were allocated to various signals squadrons and troops with the mainstay of work being the manning of base radio stations and communications centres. The deployment had a profound personal effect on many infantrymen. Private D.C. Jess of 5/7 RAR recalled of his time in Cambodia: ‘I learned there [were] no good guys or bad guys, but a lot of shady grey areas.’68 In May–July 1993 the Australian UNTAC contingent was strengthened by the arrival of an additional 155 soldiers and six Black Hawk helicopters. The reinforcement included 12 Platoon, D Company, 2/4 RAR, whose role was to ‘secure the helicopters, including static defence tasks, security patrols and the provision of a ready reaction force’.69 The Australian contingent to UNTAC returned home in November 1993.

Less than a year after UNTAC a third noteworthy operational deployment took place. On 6 April 1994, the President of the small central African nation of Rwanda was killed when his aircraft was shot down near the capital, Kigali. The incident sparked genocide as the majority Hutu population set out to eliminate the Tutsi ethnic group, branded as ‘enemies of the state’. In response to this human disaster Australia agreed to send an army medical team to support the peacekeepers of the

Two members of D Company, 2 RAR man a sentry post at night near the barracks at Battambang, Cambodia on 25 June 1993. The company deployed to Cambodia to provide security for the Black Hawk helicopters sent to bolster the Australian contingent in the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (AWM photo no. P01744.164).

Major General Guy Tousigant (left), military commander of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda, presents Corporal Brendan Reilly (right) of 2/4 RAR with his United Nations Medal. The medals were awarded after 90 days’ continuous service with the mission. The infantrymen of the contingent provided security for the medical contingent based in Kigali and escorted its members throughout the countryside (AWM photo no. MSU/94/0050/14).

United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR).70 From August 1994 to August 1995 two contingents were sent on six-month tours. Both were made up of a headquarters element, a large medical team, and a rifle company. The first group included A Company, 2/4 RAR and the second B Company, 2 RAR. The rifle companies were to ‘provide security at the Australian base at Kigali and to escort the Australian medical teams whenever they travelled to Rwandan villages providing medical assistance’.71 In 1995 six soldiers from 5/7 RAR were also deployed to Rwanda to provide APC crews for the company quick reaction force.72

Tragically, from 20 to 23 April 1995, a 50-member detachment, including infantrymen from 5 Platoon, B Company, 2 RAR were forced to witness a massacre of around 4000 Hutu refugees at the Kibeho refugee camp by members of the Rwandan Patriotic Army. Vastly outnumbered and frustrated by a mandate that did not allow them to engage the perpetrators, the infantrymen were forced into a passive role during the massacre. Throughout the carnage, however, they worked under fire attempting to assist wounded refugees. It was to their credit that the soldiers maintained discipline and restraint under circumstances that might have tempted them to take direct action.73 Only 1500 survivors of a camp of 120,000 displaced persons remained in place following the attack. In May 1995, the decision was made to cease Australian involvement in UNAMIR. Of their efforts Major General Peter Arnison, the Land Commander, noted: ‘your presence, courage, steadfastness, discipline, skills and compassion saved many hundreds of lives that would have been lost had you not been there’.74

Throughout the 1990s a combination of strategic and financial imperatives, and to a lesser extent operational experiences, encouraged a series of radical and far-reaching reorganisations within the regiment. First, by 1990, in response to the focus on defending northern Australia, the army had divided itself into a series of force element groups including Land Headquarters, the ODF, an ODF Augmentation Force, a Manoeuvre Force, a Follow-on Force and a Logistic Force Group. The highest priority group was the ODF which, based on the 3rd Brigade, now included 3 RAR. The non-ODF battalions were allocated to lower priority groups. Importantly, each group was assigned a level of preparedness in accordance with its priority that, in turn, determined manpower and resource allocations.75 This hierarchical structure ensured 1 and 2/4 RAR continued to enjoy the readiness, capability and morale implications of their ODF (RDF) status.76 Early in the decade, for example, the Townsville battalions still maintained a ‘war’ establishment of four rifle companies rather than the usual three. The commanding officer of 1 RAR in 1991, Lieutenant Colonel John Petrie, summed up the focus and confidence of 1 and 2/4 RAR in explaining that ‘as the priority . . . we must be ready to deploy quickly and successfully conduct appropriate operations’.77

With time 3 RAR’s categorisation as the third ODF infantry battalion had similar implications for its resource allocation and operational focus. Maintaining just three rifle companies in 1991 resulted in severe manning problems, with platoon strengths of between ten and fourteen in A and B Companies.78 By 1994, however, the situation had started to improve with A Company’s manning up from 50 to 101.79 According to the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Roger Tiller, in the mid-1990s 3 RAR felt the rejuvenating effects of a clear operational orientation with an ‘urgency to be ready’ giving ‘a real focus in our training’.80 Indeed, in 1996 fully manned and resourced A Company became the first to be placed ‘online’ in accordance with revised readiness requirements.81

The remaining battalions of the regiment received no such invigoration. In 1991 5/7 RAR’s A Company was designated as a training company while B Company ended the year with only two platoons and a strength of five officers and 57 men.82 The Brisbane battalions verged on obscurity. Manning difficulties forced the commanding officer of 6 RAR, Lieutenant Colonel Jim Molan, to reduce his three rifle companies to two platoons each before disbanding B Company completely in 1990. Molan complained that ‘no one sent us soldiers’ while his RSM noted the profound problem of maintaining an ‘incentive to train for war in the absence of the likelihood of operational service’.83 The early 1990s were equally difficult for 8/9 RAR with perpetual manpower problems encouraging the unit to embark on an ambitious scheme to recruit local south-east Queensland residents.84 Such ‘direct enlistment’ soldiers were to serve a minimum of four years with the unit before being considered for posting. While the concept had some success, an upcoming restructure of the 6th Brigade saw many of these ‘local’ soldiers posted away.85

The army attempted to address the clearly unsatisfactory personnel problems of the Brisbane battalions through what came to be known as the Ready Reserve (RRes) scheme. With origins dating back to the ‘latent force’ concept of the 1980s, the RRes was publicly announced by the Prime Minister, Bob Hawke, on 2 October 1991.86 In addition to resolving the 6th Brigade’s manning issues, the scheme also reflected strategic and financial imperatives in that it was to provide a low-cost solution to the manpower intensive roles and tasks of operations in northern Australia while offsetting ARA reductions resulting from the Force Structure Review.87 RRes soldiers cost around half the price of their ARA equivalents and a RRes brigade about 63 per cent of a regular formation; this meant a potential annual saving of around $76 million.88 Circumstances meant a greater concentration on reserves was inevitable and the RRes was considered the best option available.89

Under the RRes scheme soldiers enlisted for twelve months’ full-time service followed by a part-time obligation of four years (during which time they were obliged to train for 50 days per annum, a proportion of which was devoted to continuous collective activities).90 The scheme was designed to attract new recruits, particularly university students, and to encourage ARA soldiers to remain in the army upon completion of their enlistments. Financial, job search and higher education incentives were offered in the hope of building a RRes force of around 3200 soldiers over five years.91 With the 6th Brigade selected to transition to RRes status, 6 RAR, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Mark Evans, and 8/9 RAR, led by Lieutenant Colonel Peter Leahy, prepared their units for the unknown. Under the scheme the plan was for both battalions to maintain three RRes rifle companies and a support company on part-time service, along with one RRes rifle company on full-time service which, depending on the time of year (and training cycle) might be undertaking individual or collective training.92 Uncertain of what was to come many looked on the RRes with trepidation. The previous commanding officer of 6 RAR, Lieutenant Colonel Jim Molan, however, acknowledged the reality of the situation at the end of 1991 when he noted that ‘we have all discussed the Ready Reserve and we know it is better than the alternative, that is, the disbandment of the 6th Brigade’.93

The RRes enlistment target of 1056 for 1992/93 was easily met.94 Indeed, according to army recruiters about 21,000 enquiries were received for the initial intake alone. This success was partially due to an economic downturn and the fact that ARA recruitment had all but ceased.95 As well as enlisting many infantrymen who would not have otherwise joined, the regiment also benefited from many RRes soldiers opting to transfer to the ARA upon completion of their full-time year. A shortage of regular positions meant, however, that though around 630 (60 per cent of the first intake) wanted transfer only 389 were accepted.96

The first RRes soldiers began recruit training at Kapooka on 17 July 1992. Despite initial scepticism, RRes recruit training was conducted to the same program, to the same standards, and with the same emphases as its regular army equivalent. The only differences were that RRes recruits were corps ‘batched’ before they arrived at Kapooka and grouped according to their geographic area of origin. These groups were then sent to particular units to promote a sense of identity and to facilitate follow-up contact during part-time service.97 Of the 1056 RRes recruits that marched into Kapooka in 1991/92, 955 successfully marched out with the majority of graduates sent to the 6th Brigade (93 per cent). Any negative preconceptions concerning RRes recruits were soon proven false and no doubt remained that these soldiers could ‘stand beside any regular soldier and be counted as an equal’.98

Despite its achievements the RRes system was not destined to last, with the newly elected Howard Government terminating the scheme in 1996. The overall success of the experiment was difficult to measure. Certainly, the RRes increased the combined operational effectiveness of the 6th Brigade. The capability of the two RAR infantry battalions, however, did not benefit to the same extent as it fluctuated dramatically depending on the annual training cycle. The injection of numbers was, in any case, a welcome change for the Brisbane units and meant, for example, that C Company, 6 RAR was re-raised in 1992 for the first time since the Vietnam era.99 A formal Review of the Ready Reserve Scheme, submitted on 30 June 1995, concluded that it was ‘viable and should be retained’ in that it represented ‘an important intermediate capability between the ARA and GRes [General Reserve]’.100 Many ex-RRes soldiers lamented the demise of the scheme. Private Alex Scholton, 8/9 RAR, for example, noted: ‘I’m disappointed, I really am. I think the RRes was a positive influence on the defence force. I think it could have been more cost-effective but it worked’.101

Not all observers had been convinced that the RRes was the answer to the 6th Brigade’s problems. Elements within the regiment considered RRes soldiers to be motivated by money and benefits rather than loyalty or service ethic and saw the scheme as an excuse to downsize and replace ARA units.102 Such arguments were flimsy. The fact remained that the RRes ameliorated what would have been a significant reduction in army capability as reductions in the ARA were inevitable. The idea of fully manned regular infantry battalions in Brisbane was a myth and not a viable alternative. More legitimate concerns focused on the frustration and difficulties associated with adaptation on the behalf of ARA personnel unaccustomed to the RRes environment. Lieutenant Colonel Greg Baker, commanding 6 RAR in 1994, recognised this when he remarked of the scheme that ‘change within the battalion and the army is inevitable—adapting to the change is the hardest part’.103

The RRes was not the only structural imposition forced on the Brisbane battalions in the early 1990s. A second key decision was the ‘motorisation’ of the 6th Brigade. Strategic guidance demanded ‘mobile land forces to meet and defeat armed incursions at remote locations’.104 The army, therefore, required elements ‘capable of rapid deployment . . . to conduct protracted and dispersed operations’.105 The concept of a motorised formation, based on US and other international examples, evolved to fulfil this requirement. Again, financial realities lent weight to this decision. In an atmosphere of ever-tightening defence spending it was clear that the procurement of additional mobility assets like helicopters or mechanised vehicles was unlikely. The concept of motorisation, as a cost-effective option, was an attractive alternative and given the proximity of helicopters to the ODF, the strategic mobility of 3 RAR and the organic capability of 5/7 RAR, the Brisbane battalions were the logical choice. Initially there was considerable misunderstanding throughout the regiment over exactly what ‘motorisation’ meant, and, in particular, whether it might in some way equate to or replace mechanisation. The two were, however, completely different concepts. Motorisation was about strategic mobility while mechanisation concerned tactical ‘battlefield’ manoeuvre. The idea was to create a force capable of driving itself to a hostile area of operations and to rapidly redeploy within it, not one capable of mounted combat.106

Although the motorisation concept was trialled by a company from 8/9 RAR during army-level exercises in northern Australia in 1989, 6 RAR was chosen as the first unit to convert to the new role. In 1992 modified 6x6 Land Rovers were introduced into the battalion in order to develop appropriate doctrine, tactics and techniques, until the roll-out of a purpose-built infantry mobility vehicle.107 The provision of these ‘interim’ Land Rovers, at a cost of $63 million, was Phase One of a three-stage motorisation program known as ‘Project Bushranger’.108 By the end of 1992 the 6 RAR vehicle fleet had grown from 30 to 150 with the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Mark Evans, noting how far the unit had come by self-deploying into and patrolling a 200-square-kilometre area of operations during its annual exercise (a light infantry unit could patrol about twenty square kilometres). In the process the battalion was able to feed, repair, recover and refuel itself, which was ‘no mean feat for a novice motorised unit’.109 At the end of 1993 Evans reflected that ‘what motorisation has done for 6 RAR is give us the capability to pick up the battalion . . . and move it about 800 km a day for a number of days’.110 Drawing on its sister unit’s experiences, 8/9 RAR commenced its conversion in 1996.

Like the transition to RRes status not all members of 6 or 8/9 RAR understood or welcomed motorisation. Again, however, most reticence was derived from uncertainty. Corporal Scott Houstin, 6 RAR, recalled: ‘we thought it was the end of long route marches . . . but it didn’t turn out that way . . . we still do the walking and everything else . . . the vehicles are only there to get us from point A to point B. When we were first told about motorisation we didn’t realise that.’111

Misgivings were not helped by the interim Land Rovers which, designed as store carriers, had their share of problems.112 Such doubts were eased with time, familiarity and recognition of the future potential of the motorisation concept.113

As the RRes and motorisation occupied 6 and 8/9 RAR an event of considerable importance to the regiment was unfolding further north. A key product of the Defence White Paper of 1994 was the decision to raise a fifth regular army battalion. Lieutenant Colonel Ray Smith was directed to carry out detailed planning for the establishment of the new unit, subsequently identified as 4 RAR, with an initial plan to man one GRes and two ARA rifle companies in a light infantry role. A formal directive to raise the unit was released in December 1994 with Smith designated as its commanding officer and Holsworthy barracks in Sydney its home.114 The battalion was officially reborn in Townsville on 1 February 1995 with the de-linking ceremony of 2/4 RAR at Lavarack Barracks.115 With a plan to achieve full strength by the end of 1997, BHQ and Admin Company were established first, followed by the GRes A Company. In November 1995, the nucleus of B Company (ARA) was established with the second ARA sub-unit, C Company, formally raised in May 1996. Although plans to raise Support Company and D Company began in November that year, all further action was halted at this point by the implications of the RTA trial on the future role of the unit.116

As 4 RAR settled into Holsworthy barracks 5/7 RAR was ordered out. The relocation of the mechanised unit from Sydney to Darwin, as part of the wider move of the 1st Brigade, was yet another product of the strategic concentration on defending northern Australia. The issue of increasing army’s presence in the north had existed since the 1980s with the rationale that low-level threats would most likely come from that direction. A serious presence would provide familiarity with potential areas of operations and also reduce response times to any incursions.117 The battalion’s advance party moved in August 1998 and was followed by the main body between October 1998 and February 1999. The relocation involved around 500 soldiers and 250 families and was marked with a series of ceremonial activities.118 The sombre mood of the ‘goodbye to Holsworthy’ parade in late 1998 was brightened, however, by hints of an increase in priority and readiness requirements for 5/7 RAR once the move was completed.119 The relocation was a considerable dislocation for the unit in more than geographic terms. Foremost among a range of social or technical difficulties was the remoteness of the new barracks from southeastern friends, families and facilities. The ‘frontier town’ reputation of Darwin and its limited educational facilities were particularly troubling aspects for many families.120 Concerns also abounded over the stability of ammunition in extreme temperatures, training opportunities in the wet season, and live firing bans on non-government owned land.121 Such difficulties, however, while not unfounded were generally overcome. The critics were proven wrong with the battalion well and truly ensconced in its new home by the end of 1999.

While the RRes scheme, the motorisation of 6th Brigade, the re-raising of 4 RAR and relocation of 5/7 RAR were all crucial developments for the regiment, the ramifications of the Army 21 review of 1996 and the RTA plan it inspired were even more extensive. Though the RTA proposals were based on the need to detect incursions, protect key infrastructure, and use mobile response forces to intercept and defeat enemy raiders in the north, they were also motivated by fear that the army was seen as clinging to past philosophies and structures and that it was losing the battle for resources to the navy and air force.122 At its heart the RTA program involved a fundamental reorganisation of the army’s combat force. It called for mobile self-reliant battle groups capable of dispersed operations without traditional divisional or brigade organisational umbrellas.123 The concept of embedding armour, artillery and other specialist elements at a battalion level was also embraced.124 Emphasis was placed on mobility and reservist integration, while command and control capabilities were to be improved by modern military technology.125 To minimise risk a series of experiments and evaluations were conducted to assess whether the RTA initiatives ought to be implemented across the whole of the army. During this trial period high readiness units like the RDF battalions were generally left alone.

One immediate outcome of the RTA plan was the replacement of the RRes with a number of integrated GRes–ARA units.126 At formation level, the 6th Brigade was amalgamated with the GRes 7th Brigade to become the 7th Task Force. Decisions were also taken to transform 4 RAR in Sydney from a light infantry battalion to a commando unit, while 8/9 RAR was to be disbanded in July 1997.127 The dissolution of 8/9 RAR was the first time a regular infantry battalion had been removed from the army’s order of battle since the establishment of the ARA and RAR. The despair of current and ex-serving members of the unit was overwhelming at the time and lingers to this day (although in 2006 the government foreshadowed the re-raising of 8/9 RAR). On 18 June 1997, a final tribute parade to the battalion colours was conducted before they were laid up at the infantry corps museum at Singleton.128

Responsibility for trialling RTA command-and-control arrangements resided with the 1st Brigade, while 6 RAR was chosen to evaluate integration at a battalion level.129 Within the 1st Brigade the trials had a particular impact on the newly relocated 5/7 RAR. RTA experiments immediately reduced the battalion from three mechanised companies to two, with Reconnaissance Platoon and B Company amalgamated and redesignated as Reconnaissance Company.130 The unit’s mortar fire controllers and signals platoon detachments were absorbed into the mechanised companies and a sniper section was introduced for the first time.131 Already in a state of transition due to its move to Darwin, the unit had to deal with a degree of uncertainty. With uncertainty, however, came opportunity. The commanding officer in 1998, Lieutenant Colonel W.T. Bowen, considered that

the trial offers us the opportunity to demonstrate the vital capability offered by mechanised infantry . . . the role of mechanised infantry has always been down-played within our army, due to the . . . excessive interest in light infantry organisations. There now appears to be an understanding of the technology offered, and the combat capability provided, by modern mechanised infantry.132

In Brisbane the RTA trials had an even greater impact on 6 RAR as it tested the integration of various non-infantry arms and services within the motorised battalion group from July 1997. Armoured, artillery, intelligence, engineer and signals corps personnel—along with their attendant equipment—were all placed under the command of the commanding officer. The unit’s infantry-manned Support Company was replaced with ‘Fire Support’ and ‘Reconnaissance/Surveillance’ companies. The former contained towed artillery and a troop of LAV–25 light armoured vehicles. The latter held a troop of engineers (replacing Assault Pioneer Platoon) and a dedicated Reconnaissance/Surveillance Platoon containing a number of six-man patrols, a sniper section, an unmanned aerial vehicle section and mix of surveillance devices including unattended ground sensors and ground surveillance radars.133 In BHQ the old infantry positions of intelligence officer, intelligence sergeant and regimental signals officer were replaced with intelligence and signals corps personnel.134 These embedding experiments were tested in a range of ‘protective’ exercise scenarios in 1998.135 These led the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel John Edwards, to conclude that while organic artillery or armoured assets were successful, they gave no advantage over traditional ‘direct’ support relationships. Meanwhile there were some clear costs in barracks, mainly in relation to economies of scale, breadth of training and equipment management. Edwards concluded, however, that ‘combat engineers, and the signals, intelligence cell and nursing officer should be introduced to all infantry battalions’.136

In the end the RTA experimentation amounted to little. Towards the end of 1999 the government’s strategic reorientation and a developing situation in East Timor focused the army on offshore readiness. As a consequence ‘the Regiment’s battalions in the north received all the attention’ and interest in the RTA trials subsided.137 Scheduled evaluations had ceased in the 1st Brigade at the end of 1998 and in the 6 RAR embedding trial in November 1999. Two key factors militated against widespread uptake of the RTA concept. First, the decentralisation of specialists and their equipment ran contrary to long-established military wisdom and, second, the question remained as to how effective structures tailored specifically to defend northern Australia from low-level threats would be in operating in conventional or coalition operations overseas.138 The new requirement was for a flexible force capable of overseas deployment and a return to a more familiar force structure was deemed most appropriate.139

While the experimental structures trialled by 5/7 and 6 RAR may not have endured, the RTA plan for 4 RAR in Sydney certainly did. With no testing or evaluation caveats, the newly re-raised unit was ‘increased in strength and converted into a regular commando battalion’.140 At its birthday parade on 1 February 1997, the Land Commander, Major General Frank Hickling, officially re-titled and re-roled it 4 RAR (Commando).141 According to the Commander Special Forces, Brigadier Jim Wallace, the special forces community had always intended 4 RAR to take such a path and viewed giving the regiment a slice of ‘special’ capability as a necessary concession in order to overcome the intransigence of mainstream infantry-oriented decision makers. He noted:

our first priority was, of course, to raise a second commando regiment, but it soon became clear that to get the infantry ‘mafia’ behind the proposal we needed to re-raise 4 RAR and make it a commando regiment. Like good Special Forces soldiers we decided the objective was what mattered and took the path of least resistance.142

For many observers the requirement for an infantry-based capability trained in commando-style operations such as securing sea points of entry had been highlighted by Operation Morrisdance in May 1987. Although vindicating 1 RAR’s readiness and conventional training, a lack of expertise in amphibious warfare and ship-to-ship transfers was clearly evident. The need to free the SAS of some responsibilities and adding to the nation’s counter-terrorist capability also carried weight.143

Following the announcement of its new role 4 RAR embarked on an immediate structural overhaul. C, D and Support Companies were disbanded to swell B Company into its new establishment of 172 personnel. Regular members of the former light infantry unit were given a choice of attempting commando training or transferring to other battalions. With GRes positions no longer available part-time personnel were discharged or posted. Much of this transformational period was supervised by Lieutenant Colonel Neil Thompson as commanding officer and WO1 Al Forsyth as RSM. The SAS experience of both men, and that of the second-in-command, Major Marty Colyer, eased 4 RAR’s passage into the special forces community considerably.144 The soldiers of B Company, under the command of Major Shane O’Brien, began individual commando training in March 1997 with the first group gaining their qualifications by June.145 Lance Corporal D.R. Etheridge became the first 4 RAR soldier to attain a commando classification with around half of the company’s original 121 volunteers eventually achieving similar success.146 The pace of battalion life during these developmental years was hectic. Corporal Brian Smith noted that ‘doing course after course and losing your mates to injury along the way can get pretty depressing’.147 Nonetheless, by 1998 4 RAR had raised two commando companies (B and C Company), on an alternating high readiness notice.

The 1990s were characterised by significant technological innovation for the infantrymen of the regiment. Procurement of high technology equipment occurred (despite an overall scarcity of financial resources) as a result of an understanding that new technology was essential to protecting the country’s northern approaches, and secondly, because operational experience had shown the clear utility of suitable technology to the infantry. Immediately prior to its deployment to Somalia 1 RAR received a considerable amount of advanced equipment that proved invaluable during the operation, including a data transfer system, thermal imagers and global positioning systems (GPS).148 Night vision technology in particular provided an important tactical edge and many important activities, like night counter-ambush patrolling, would have been far less effective without it.149 Whilst Somalia highlighted the value of these technologies, it also underscored the army’s shortcomings in this regard, and providing the battalion with enough equipment had stripped the rest of the army bare.150 Early in the deployment the contingent also found itself unable to receive information, including operational orders, because it possessed no computers able to link with the US network.151 These visible technological deficiencies were a warning for the army that was, in the main, heeded.

Evidence of the army’s desire to modernise the infantry force following Operation Solace was abundant. Project Ninox, for example, was initiated to equip the army with modern third generation night vision technology on a far greater scale than previously. Ninox trials ran throughout the decade with equipment coming into service in 1999. The project introduced not only night vision goggles but also night aiming devices for individual weapons, night observation systems, perimeter surveillance equipment, new thermal imagers and unattended ground sensors. These tools gave the battalions a true ability to operate round the clock and gave them hitherto unachieved flexibility.152 Another useful item of equipment brought into service throughout the 1990s was the ‘Infantry Weapons Effects Simulation System’ which, by virtue of a laser/sensor system linked to blank firing weapons, added realism in training and helped teach infantrymen the finer points of cover, fire and movement.153 New communications equipment was also introduced. New high-frequency and very high-frequency radios replaced their Vietnam era equivalents, while the new Pintail lightweight radios were procured for intra-platoon communications.

Perhaps the most important technological innovations of the decade concerned weapons. The Steyr AUG (F88) assault rifle and the FN Minimi Light Support Weapon (F89) replaced SLR and M16 rifles, M60 and FN MAG 58 General Purpose Machine-Guns, and the F1 submachine gun within the infantry battalions.154 6 RAR received F88s in January 1989 and F89s in April 1990 in order to conduct field trials before they entered wider service in 1991–92, giving every infantryman in the regiment a personal automatic weapon.155 There was some initial debate as to what these new weapons added to the combat capability of the individual soldier, section and rifle platoon. There was no doubt that with its compact ‘bullpup’ design, optical sight and light recoil the F88 brought much higher shooting standards but, despite this, many ‘old timers’ feared the reduced ‘hitting’ power of the new weapons as compared to their predecessors. Ballistic evidence and operational experiences in Somalia showed they need not have worried.156 Importantly, the allocation of two individually operated F89s rather than one crew-served MAG 58 represented a significant increase in combat power, flexibility and tactical versatility for the basic infantry section. Rather than a ‘scout group’ and ‘rifle group’ manoeuvring under the cover of automatic fire from a ‘gun group’, the F89 allowed for the creation of two equally capable ‘fire teams’ under the direction of ‘command group’. The F89 was also specifically designed to engage point targets, by far the most likely to be encountered by an infantry section on most operations, rather than area targets envisaged under the ‘machine gun theory’ of the MAG 58. It was only in area defence or suppression of area targets where the older weapon’s superior range and strike patterns were a distinct advantage, and it was this characteristic that ensured the MAG 58 remained in battalion support companies in a sustained fire role.157

As new infantry weapons were introduced a number of antiquated systems and capabilities were withdrawn from service. First, given the focus on low-level operations in northern Australia and the limited armoured threat it implied, the anti-armoured and sustained fire machine-gun platoons, with the exception of 5/7 RAR, were merged into direct fire support (DFSW) platoons which, armed with the MAG 58 and 84 mm Carl Gustav, assumed both roles.158 The Milan anti-tank guided missile inherited by 5/7 RAR in 1988 was also retired during the early 1990s due to the cost of live firing the missiles during peacetime training.159 Unfortunately, despite a clear and continuing requirement no replacement weapon was identified for the M203 grenade launcher, lost with the introduction of the F88, while stocks of M2A1–7 flamethrowers were removed from the battalions due to political and social sensitivity over the employment of this nature of weapon.160

In the second half of the decade particular attention was paid to technologies to improve the capability of the individual infantryman. Project Wundurra, for example, began in the late 1990s to exploit a range of emerging technologies. Under this program, in May 1997, a platoon from C Company, 5/7 RAR was used to evaluate a range of equipment including electronic weapon sights and mounted thermal imagers linked to ‘heads-up-displays’. Section commanders used small computers with digital maps and inbuilt GPS while intra-section communications, video imaging equipment, thermal camouflage and positive location devices were scheduled for future evaluation.161 In late 1998 the British AW-F sniper rifle system (SR98) replaced their aging Parker Hale equivalents while, from 1999, two F88s and both F89s within each infantry section were fitted with the Picatinny Rail sight mount allowing for the attachment of the Wildcat enhanced optical sight and additional night vision equipment.162

The manner in which the regiment trained in the 1990s was also subject to influence by high-level strategic/financial guidance and operational experience. At the highest levels Exercises Kangaroo 92 and Kangaroo 95 were the last of the series of nine conducted from 1971 to test the army’s ability to defend continental Australia. The former, although on a smaller scale than its predecessors, was a diverse experience for the RAR battalions. It provided the opportunity for 6 RAR to showcase its new motorised capability and strategic manoeuvrability.163 On the other hand, without such mobility, the soldiers of 3 RAR saw precious little action. The unit’s DFSW Platoon reflected: ‘we were prepared for the expected . . . onslaught but alas we had to make do with sand flies and ticks’.164 The Townsville battalions were more central to the activity. 1 RAR conducted amphibious landings, clearing operations on Bathurst and Melville islands, and a battalion attack to conclude the exercise.165 As usual oppressive heat and humidity were a challenge to all participants as infantrymen endured two-metre-high spear grass on patrol and boiled in static armoured vehicles or in weapon pits where temperatures soared to the mid-50s.166

Exercise Kangaroo 95 was the most complex, largest, and last of its type conducted. The activities of 2 RAR during the exercise represented those of the regiment as a whole. The battalion was tasked with protecting the coastline of the Gulf of Carpentaria while defending industrial interests and the civilian population around Weipa. Aggressive patrolling was seen as the key to preventing enemy incursions and foot, vehicle and water operations, along with observation posts and vehicle check points, featured heavily in the unit’s plans. A reaction force was maintained and reconnaissance assets deployed deep into the area of operations. The flexibility of the fledgling DFSW concept was well illustrated through the provision of mobile gun lines and convoy protection. Interestingly, given the ongoing development of motorisation by the Brisbane battalions, the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Dick Wilson, reflected that ‘it was difficult to operate in Cape York with the limited mobility we had . . . the exercise highlighted the battalion needed a more tactical, mobile vehicle’.167

The other army-level exercise of importance to the regiment in this era was Exercise Phoenix conducted in the Northern Territory in September 1998 to validate a range of RTA concepts.168 Phase One of the exercise saw the 1st Task Force (1st Brigade) and 6 RAR pursuing small enemy patrols around northern Australia while Phase Two scripted a series of small-scale attacks against 1st Task Force assets. Phase Three was to be the culmination of the activity with around 2000 task force troops scheduled to attack 3 RAR in Tennant Creek. The exercise, however, was beset with problems with the final phase not physically executed and 3 RAR returning home without a fight. The battalion’s operations officer, Major Grant Sanderson, cynically observed that ‘1 Task Force proved 2,000 could beat 250 as long as they stood still long enough and were good enough to only come lightly armed’.169 Despite its limitations the exercise identified a number of important lessons for dispersed operations.170

At the brigade level a number of quite distinct and stylised exercises were a feature of regimental training. For the RDF the Exercise Swift Eagle series, as a deployment test activity, was the premier event. Exercise Swift Eagle 98 was an illustrative example of the size and nature of the series towards the end of the decade. It involved an amphibious lodgement to assist the government of a failing

Two soldiers from 1 RAR train at the MOUT (Military Operations in Urban Terrain) facility at the High Range Training Area near Townsville in 1998. The facility had been completed in 1997 largely as a result of operations in Somalia where the lack of training in this type of operations had been evident. The deployments of the 1990s influenced the training directions later in the decade and did much to prepare the regiment for the challenges in the new century (Department of Defence photo no. TOWD_98_003_18).

Pacific neighbour while evacuating Australian nationals. It began with a seaborne lodgement by 1 RAR, quickly reinforced by 2 RAR, followed by airmobile deployment throughout the troubled fictional province. The friendly force then attempted a five-pronged simultaneous services protected evacuation (SPE) under pressure from ‘locals’ making the operation as difficult as possible. Following the SPE a range of conventional skills were practised.171

Because of the RRes scheme, brigade level training for 6 and 8/9 RAR was based for much of the decade on an annual concentration period of 30 to 35 days known as Exercise Ready Shield. Reflecting the current thinking, these exercises were generally orientated towards low-level operations and vital asset protection. The last such activity, Exercise Ready Shield 97, was the largest motorised exercise ever conducted in Australia, and a mix of 2500 RRes and 1150 ARA soldiers (with 824 vehicles) deploying 2200 kilometres from Enoggera to an area of operations that stretched from Woomera to Port Augusta to Broken Hill. A range of tactical concepts were practised including security at points of entry into an area of operations, vital asset protection, and live firing at the Woomera rocket range. The redeployment back to Brisbane after the exercise signalled the wind-down of the RRes and the end of the Ready Shield series.172

In the 1st Brigade the Predator and Tiger family of exercises were used to practise combined arms mechanised infantry/armoured operations between 5/7 RAR, 1st Armoured and 2nd Cavalry Regiments. In 1994, 5/7 RAR featured in Exercise Desert Tiger, which involved the biggest mechanised battle group deployment outside of the Kangaroo series. The activity highlighted the unit’s ability to deploy rapidly using organic and external transport (including C–130 aircraft) and introduced the battalion to low-level operations.173 Given the nature of mechanised operations purely ‘unit’ training was a rare event for 5/7 RAR. More often than not even sub-unit training involved a level of mechanised infantry/armoured cooperation. Reinforcing this, from 1993, the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Gary Byles, deliberately encouraged a narrow ‘mechanised’ focus.174 Although conceding this was done ‘at the expense of other skills’ he believed ‘our priorities must lie in providing that unique capability that no other unit can offer’.175

Following the 5/7 RAR example, at the unit level individual battalion specialisations and characteristics tended to encourage unique training schemes. The exception to this rule were the sister RDF battalions, 1 and 2/4 RAR (2 RAR from 1995). Both were light infantry units with an emphasis on amphibious and airmobile operations and both tended to follow an annual cycle working on two-month periods, with section and platoon training in February through to unit-level training in July.176 The early 1990s brought a concentration on SPEs in the 3rd Brigade that, in time, was replicated across the regiment. The Townsville soldiers, being used to more traditional roles, did not initially embrace such a focus. According to the commanding officer of 1 RAR, Lieutenant Colonel Hurley, ‘to be placed in a situation where they were in the front line facing and assisting a lot of civilians was a bit of a shock’.177 Emphasis was placed on reducing levels of aggression and developing appropriate skills for managing civil–military interaction. Fortuitously, this emphasis stood 1 RAR in good stead for Operation Solace. After the deployment Hurley admitted ‘the long hours in helmet and flak jacket paid dividends in the streets of Baidoa’.178

Unit training programs at 3 RAR roughly paralleled those in Townsville without the concentration on amphibious and airmobile operations. In their place the unit practised its airborne role, which was annually put to the test in the Swift Canopy exercises. The training differences between 3 RAR and the Townsville battalions, therefore, revolved primarily around the means of entry into an area of operations rather than any difference on the ground. Exercise Swift Canopy 98 illustrated how 3 RAR’s airborne capabilities were an adjunct to, rather than a replacement for, traditional light infantry training. There a company airborne assault secured an airfield point of entry for the remainder of the battalion, which was followed by a 50-kilometre tactical advance to contact. Patrolling (including mounted APC and water patrols) was a feature with a comprehensive live firing program supported by F–111, artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire.179 The activity proved, according to the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Nick Welch, that ‘as a light infantry battalion’ 3 RAR was both ‘capable and adaptable’.180

For 4 RAR from 1997, as part of the special forces organisation, unit and sub-unit collective training activities became important. It was some time, however, before they could get under way with the exhaustive range of individual training required to achieve commando qualifications keeping such activities to a minimum. In 1998 4 RAR focused its training on consolidating a commando capability at a company level (B Company) while continuing to support the individual commando training courses. Exercise Red Pegasus, in March that year, was the first opportunity for the battalion to collectively exercise its commando role, and all parachute-qualified personnel conducted a series of combat water descents designed to build up skills for future parachute operations.181

Before the RRes scheme, unit training for 6 and 8/9 RAR was conducted as best it could given the serious manpower constraints of the 6th Brigade. The commanding officer of 6 RAR, Lieutenant Colonel Jim Molan, described his yearly program in 1990 as ‘exposing the current generation of 6 RAR soldiers to tactical activities in the four phases of war’.182 This included a continuing concentration on combat fitness with the conduct of annual 80-kilometre route marches.183 While 6 RAR marched 8/9 RAR was deeply involved in the Papua New Guinea Training Program. Under this scheme the battalion provided instruction in close country and conventional operations to PNG infantrymen.184 Following the introduction of the RRes, when not exercising collective skills during the annual Ready Shield concentration, both 6 RAR and 8/9 RAR busied themselves with individual and small group training made necessary by the inability of the School of Infantry to cope with the expanded number of new RRes infantrymen coming to the corps.185 Following the collapse of the RRes and disbandment of 8/9 RAR, 6 RAR focused its attention on low-level operations, motorisation and the RTA trials.186

The 1990s was a tumultuous time for the regiment. The decade was characterised by the ramifications of a strategic concentration on protecting northern Australia at minimum government expense. Ironically, despite this inward focus, significant operational opportunities were presented in Somalia, Cambodia and Rwanda. The experiences gained from these deployments became a third influential factor in shaping the regiment in this period. Protected by their RDF status, the Townsville battalions suffered far less structural upheaval than the remainder of the regiment during the decade. After a period of consolidation in the early 1990s, and once it had fully grown into its role as a supplementary battalion of the RDF, the same was true of 3 RAR. The period was far less stable for the other RAR battalions. The RRes, RTA trials, the relocation of the 1st Brigade to Darwin, motorisation, the raising of a commando capability and the disbandment of 8/9 RAR brought both opportunity and uncertainty to the regiment. Strategic, financial and operational developments had the additional function of encouraging the embrace of emergent military technology. Similarly, these three factors influenced and conduct of infantry training at all levels. Turbulent as the 1990s were, the regiment emerged from the decade as a more specialised, operationally ready and capable combat force than it had been in 25 years.