15

Near and Far

Operations, 1999–2006

John Blaxland

For the Royal Australian Regiment the 1990s had been tumultuous. Though 1 RAR had a tour of duty in Somalia in 1993, and elements of 2 RAR served in Rwanda in 1994–95, in the main the battalions followed the pattern of the post-Vietnam period, concentrating on training and enduring periodic reorganisations. In the seven years from 1999, however, the battalions of the regiment experienced an unprecedented period of operational service. The ethos of the battalions underwent a remarkable change. Officers, NCOs and soldiers now expected to be deployed on operations at some stage in their service. The operational experience also resulted in further changes to the battalions’ structures and operational concepts. These changes proved to be some of the most fundamental to affect the regiment since the restructure of the army in 1964 after the abandonment of the pentropic experiment.

This chapter reviews how that took place, considering the RAR’s experience in East Timor, the Solomon Islands, the wider Pacific area and the Middle East, as well as the raising of 4 RAR as a commando unit and the organisational challenge associated with the Hardened and Networked Army (HNA) concept. The chapter ends with the announcement of the expansion of the regiment by two battalions. One of the key events to shape the RAR in this regard was the commitment to East Timor, commencing in September 1999.

2 RAR and 3 RAR in East Timor from September 1999

In 1999 Indonesia, under President B.J. Habibie, agreed to a ballot over East Timor’s future as part of Indonesia. It was conducted on 30 August 1999 under the auspices of the unarmed United Nations Assistance Mission in East Timor (UNAMET). A few days prior, the online parachute company—B Company, 3 RAR under Major Stephen Grace—was ordered to prepare to deploy to an as yet unannounced destination. Pre-positioned at RAAF Base Tindal, south of Darwin, the company joined an SAS squadron to form Joint Task Force 504 for a potential service protected, or assisted, evacuation. The evacuation plan, named Operation Spitfire, was not well known to the public at the time as the media remained more interested in events at Robertson Barracks on the outskirts of Darwin.1

The ballot, the result of which was announced on 4 September, indicated that 78.5 per cent of those who voted refused Indonesia’s special autonomy offer. This seemed to lay the path to East Timorese independence, but within hours militia gangs started a rampage, killing hundreds if not thousands in the process. Within the next few days the overwhelming majority of international observers, journalists and civilian personnel of UNAMET fled from the territory. By 7 September, a seaborne evacuation option was being considered and half of B Company, 3 RAR— accompanied by a special forces liaison team and an intelligence detachment— moved to Darwin to board the high-speed catamaran HMAS Jervis Bay. The half-company group sailed in Jervis Bay three times, each time approaching the territorial waters of East Timor before being ordered back to Darwin.2

In the meantime, the 3rd Brigade ready battalion group, 1 RAR, under Lieutenant Colonel Mark Bornholt, had been conducting extensive force preparation in case of a short notice requirement to deploy to East Timor. Its ready company group, B Company under Major Jim Ryan, was the first element called for under Operation Spitfire and it prepared to deploy to Dili on 7 September to provide security to the Australian consulate, only to be held at Tindal like B Company, 3 RAR, awaiting further clearances. The wait at Tindal turned from days into weeks as the company was allocated different missions that never eventuated.3 In the end, the well-publicised evacuation operation proceeded on a greatly reduced scale, utilising RAAF C–130 aircraft, a handful of SAS soldiers and one member of 3 RAR, Sergeant Shane Armstrong, who was attached as a sniper and to conduct a reconnaissance.

Under intense international pressure, Habibie announced on 12 September 1999 that Indonesia would accept an international peacekeeping force for East Timor. Then, on 15 September, the United Nations Security Council authorised the deployment of a peace enforcement force under Chapter 7 of the UN Charter. The International Force in East Timor (INTERFET) was authorised to deploy with the intention of being replaced as soon as practicable by a United Nations peacekeeping mission. As Operation Warden, INTERFET started to deploy on 20 September, with contingents from Australia, Britain, the United States, the Philippines, Canada, New Zealand, Thailand, Italy, Brazil and France under the command of Major General Peter Cosgrove. The force would eventually include representatives from 22 nations.

Meanwhile, in Townsville, a dejected 1 RAR handed over responsibilities for being the Ready Deployment Force’s ready battalion to 2 RAR on 13 September as per the brigade commander’s predetermined handover for ready-battalion responsibilities. On 23 September B Company, 1 RAR returned to Townsville having spent almost four fruitless weeks in Tindal on stand-by for three different operations, including two weeks as the INTERFET reserve.4

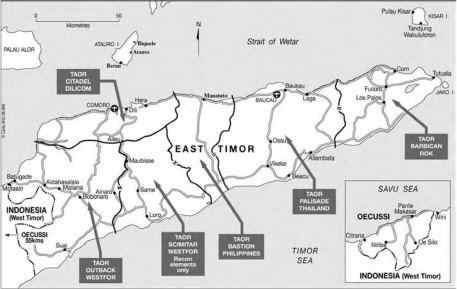

MAP 11. East Timor. The first Australian troops, part of INTERFET, deployed to East Timor in September 1999. 2 RAR, 3 RAR and 5/7 RAR all served as part of INTERFET during 1999–2000. Subsequently 1RAR, 2 RAR, 3 RAR, 4 RAR, 5/7 RAR and 6 RAR all served in East Timor under the series of UN missions to the country (UNTAET and UNMISET) from 2000 to 2003. In 2006, 3 RAR, with elements of 1 RAR, 2 RAR and 4 RAR, deployed again to East Timor as part of Operation Astute.

2 RAR, under Lieutenant Colonel Mick Slater, and the remainder of 3 RAR were soon warned for deployment to East Timor, however. On 20 September the special forces response force, based around a SAS squadron, deployed to secure Dili’s Comoro airfield. They were soon followed by Major Dick Parker’s A Company, 2 RAR, the battalion tactical headquarters, and two APCs from B Squadron, 3/4th Cavalry Regiment, flying straight from Townsville. The rest of the battalion soon followed by C–130 Hercules flights. Shortly afterwards, C Company, 2 RAR, under Major Jim Bryant, deployed from the airport, under Indonesian military (Tentara Nasional Indonesia—TNI) escort, to the landing point for 3 RAR, the port facilities in central Dili. Lieutenant Colonel Nick Welch’s 3 RAR arrived in HMAS Jervis Bay on 21 September, having been pre-positioned in Darwin as a battalion by 17 September—partly in case their parachute capability was required. 3 RAR relieved 2 RAR of the task at Dili Harbour pier, INTERFET’s sea entry point, before expanding into the town to occupy what was aptly named AO Faithful.

The deployment of the two battalions (with 108th Field Battery operating as an infantry company as part of 3 RAR), supplemented by a reinforced British Gurkha company group and RAAF airfield defence guards, enabled INTERFET to begin the process of restoring law and order. This involved conducting patrolling, vehicle checkpoints, disarming members of the militia and apprehending them. Sporadic gunfire continued and smoke still billowed from gutted buildings as patrols uncovered bodies, some mutilated, around the Dili area. With news of unrest continuing in the eastern end of East Timor, on 22 September A Company, 2 RAR, under Major Parker, conducted an air mobile operation to secure Baucau airfield, thus demonstrating INTERFET’s ability to move swiftly and decisively. Three days later the company handed over the airfield to Filipino infantry and returned to Dili.

In the meantime, on 24 September, Commander 3rd Brigade, Brigadier Mark Evans, became concerned that his forces did not have the initiative and organised a brigade-level sweep of Dili called Operation Brighton, involving 2 RAR, 3 RAR and the Gurkhas, in conjunction with the available aviation assets. The sweep, conducted despite the continued TNI presence inside the cordoned area, served to imprint INTERFET’s authority across Dili without a shot being fired in anger. As a result TNI roadblocks were removed and considerable numbers of militia weapons were recovered. As Evans’s brigade major, Marcus Fielding, observed, ‘the previous night there were trucks, rifle fire and arson. 24 hrs later later, nothing—beautiful! It was a real watershed.’5

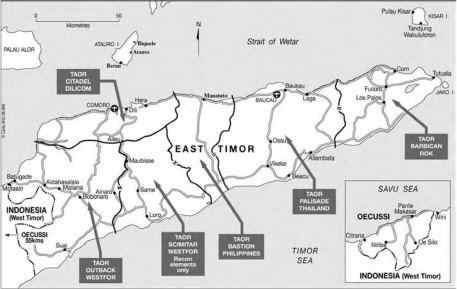

Members of 3 RAR searching buildings for pro-Indonesian militia members in Dili, East Timor in September 1999. Ending the chaos brought by the militias and detaining their members were among the most important tasks undertaken by the regiment during the early days of the INTERFET mission, the first major deployment of the army since the Vietnam War (photo: Stephen Dupont, AWM photo no. P04315.040).

Following the success of the sweep General Cosgrove felt confident to commence planning to redeploy elements from Dili to the western border region of East Timor adjoining the Indonesian province. For Brigadier Evans the concept of operations on the border was to cascade battalions from north to south.6 West Timor was where the militia were known to have fled along with tens of thousands of East Timorese who were forcibly removed between the time of the ballot and the arrival of INTERFET. On 27 September D Company, 2 RAR, under Major Terry Dewhurst, deployed by air to the border region supported by a road move through the coastal village of Liquica.

On 30 September 2 RAR handed over their remaining responsibilities in Dili to 3 RAR and prepared to relocate to the border area. Operation Lavarack took place on 1 October with the insertion of 2 RAR battalion headquarters and the remaining three rifle companies into the largely deserted Balibo region. The headquarters was established in the 400-year-old Portuguese fort at Balibo overlooking the coastal border strip between East and West Timor, and adjacent to the site where Australian journalists had been killed in 1975.

As part of the same deployment Major Bob Hamilton’s B Company, 2 RAR moved by road from Dili to Batugade, a town that had suffered much devastation during the post-ballot period. The next object, under Operation Chermside, was the deployment of A Company, 2 RAR to the deserted town of Maliana. Shortly afterwards, on 15 October, 3 RAR conducted an air mobile insertion to relieve A Company, 2 RAR in Maliana with the rifle companies of 3 RAR deploying into dispersed areas of responsibility.

Before the relief was in place by 3 RAR, however, elements of 2 RAR became involved in a border incident. On 10 October 1999, C Company, under Major Jim Bryant, conducted a patrol, following reports of Indonesian military and militia activity in the village of Motaain, adjacent to the border with West Timor. Accompanying Bryant was the officer commanding Support Company, Major David Kilcullen, a fluent bahasa Indonesia speaker. 8 Platoon, under Lieutenant Peter Halleday, was tasked to patrol along the main road, with linguists in support, and secure the entrance to the village. The linguists were then to ascertain whether or not reports of ill treatment of villagers were accurate. As the platoon approached the village the militia fired upon it from its front and right, as well as sporadically from the rear. The platoon returned fire, prompting the militia to withdraw from the village by truck. As a result of the contact an Indonesian police sergeant was killed and two others seriously wounded. The lead Australian section commander, Corporal Paul Teong, was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his leadership under fire.

Shortly afterwards, on 16 October, an SAS patrol was fired upon in 2 RAR’s area of operations near the village of Aidabasalala, north-east of Balibo. The incident has correctly been portrayed as involving much bravery on the part of the SAS soldiers involved, but it also undermined an imminent battalion operation planned by 2 RAR aimed at not only stirring but also capturing the remaining active militia in the area.7 The lack of coordination with 2 RAR left many frustrated that an opportunity to capture a significant militia element had been missed. Indeed the response force’s tendency for moving through other units’ areas without clearance or permission, with its inherent potential for fratricide, was a source of considerable concern for the infantry battalions. The incident demonstrated the need for closer collaboration between the ‘special’ and ‘conventional’ forces.

A few days later, on 21 October, Major David Rose’s C Company, 3 RAR set out on Operation Strand. This operation was conceived as a show of force in an area allocated to the 1st Battalion, Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment (1 RNZIR), which was not yet in place except for the lone New Zealand company in Suai. Deploying to Belulik Leten by Black Hawk helicopters, the company came under fire from militia heading from West Timor into East Timor wearing dark coloured uniforms and carrying M–16 and AK–47 rifles. Rose ordered one of his platoons to flank the militia using dead ground, but the militia withdrew back into West Timor, firing at the Australians and using civilians as shields from return fire. Due to restrictions on INTERFET movement up to and beyond the border there could be no pursuit and no militia were captured or killed. Nonetheless, the operation did demonstrate that the militia groups were no longer free to roam with impunity. The incident also involved the first shot fired in anger by 3 RAR since the Vietnam War.8 Incidentally, the WESTFOR group, under the Townsville-based Headquarters 3rd Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Evans, which included forces from Australia, Britain, Canada, New Zealand and even a small element from the United States, was the first time since the Korean War that the forces of all these nations had served on operations in the same formation.

A few weeks after the Belulik Leten incident, on 10 November 1999, 2 RAR was reassigned responsibility for Maliana to allow Major Stephen Grace’s B Company, 3 RAR, to participate in Operation Respite, a two-phased air mobile insertion into the Oecussi enclave. 3 RAR was to relieve the British Gurkha company and the enclave headquarters element based on Lieutenant Colonel Mick Crane’s Headquarters, 4th Field Regiment. The redeployment to the enclave required a handover of 3 RAR’s AO to 2 RAR and elements of 1 RNZIR, which had now completed its arrival into East Timor. Incidents occurred on the border of the Oecussi enclave over subsequent weeks but the Australians under Lieutenant Colonel Nick Welch, and subsequently Peter Singh, gradually asserted greater control over the border areas and checked the occasional militia incursions.9 The remaining time in East Timor for 2 RAR and 3 RAR saw the companies conduct extensive patrols in their respective border areas prior to their return to Australia early in 2000. Their important work and quick deployment out of Dili to the border areas could not have been possible, however, without the prompt and capable support and relief of duties in the Dili area provided by 5/7 RAR.

5/7 RAR in East Timor, 1999–2000

The first few months of 1999 saw 5/7 RAR completing its move from its home of 26 years in Holsworthy to new purpose-built lines in Robertson Barracks, in the Darwin suburb of Palmerston. The potential crisis looming in East Timor had demanded that 1st Brigade train and be resourced to be part of the Ready Deployment Force. This meant a considerable amount of additional work for the soldiers of 5/7 RAR, already under some pressure to settle quickly into their new home.10 That readiness process stood the battalion in good stead for what lay ahead because 5/7 RAR, under Lieutenant Colonel Simon Gould, was warned for service in East Timor with 21 days’ notice to move in September 1999. The battalion reached East Timor fourteen days after the soldiers of 2 RAR and 3 RAR, with the advance party arriving on 7 October and the first companies landing on 9 October. Within hours of arrival, the first of 5/7 RAR’s M113 APCs started patrolling around Dili. The vehicles moved slowly and very deliberately, generating a rumble that left a distinct impression on all sides. With four mechanised rifle companies, 5/7 RAR was able to dominate an area that previously had taken several battalions to control.11

With HQ 3rd Brigade deployed to the border region, an ad hoc formation, Dili Command, under the command of the New Zealander Brigadier Martin Dunne, was established to provide security to the capital and surrounds. 5/7 RAR was allocated to Dili Command as its only infantry battalion and therefore carried the bulk of the required work. On 23 October 5/7 RAR was tasked to provide the coordination and security for the return of Xanana Gusmao to Dili, together with specialist elements of Lieutenant Colonel Tim McOwan’s response force. A week later the battalion was fully occupied with ensuring that the last remaining elements of the TNI were ushered away from Dili without destroying prominent buildings, barracks and, potentially, the evidence of their previous activities. Having lost the ability to provide for their own safety, the Indonesians needed a secure environment provided to them to enable them to depart unmolested. As arrangements constantly changed the flexibility of the mechanised companies proved critical. There was a great sense of relief amongst the battalion as the last of the TNI and officials departed East Timor in the early hours of 31 October 1999 under the careful eye of the mechanised infantrymen.12

In January 2000, the battalion moved into the northern sector of the border area with West Timor, the primary tasks being to control passage across the 57-kilometre length of border assigned to the battalion and to maintain security in the area. Their predecessors, 2 RAR, had approached its task essentially as a counterinsurgency operation, using an ‘ink spot’ method of deploying stealthy company and platoon patrols. But once it was assessed that neither the militia nor the TNI posed a serious threat, and buoyed by the success of their approach of the last three months under Dili Command, 5/7 RAR took a different approach. This involved taking steps otherwise considered tactically unsound but intended to build confidence among the locals—such as using white light at guard posts at night.13 Conscious of the challenges 2 RAR had encountered in coordinating events with response force elements, Gould invited the collocation of a response force headquarters element with him in Balibo to enhance coordination. It was accepted as marking the beginning of a close working relationship.14

When INTERFET handed control of East Timor to the United Nations Transitional Authority in East Timor (UNTAET) on 21 February 2000, 5/7 RAR became part of UNTAET’s multinational peacekeeping force, donning blue berets and UN sleeve badges. The force came under the command of Thai Lieutenant General Boonsrang Niumpradit, with Australia’s Major General Mike Smith (a former commanding officer of 2/4 RAR) as the deputy force commander. During this period, in an apparent attempt to test the UN’s mettle, a spate of provocations took place, with returning refugees being intimidated and shots deliberately fired over the heads of troops and refugees at a pre-planned ‘family reunion’ at a border checkpoint. In that instance, Gould, the operations officer, Major Shane Gabriel, and the RSM, WO1 Rod Speter, boldly strode forward towards the Indonesians calling for them to cease fire—which they did after expending more than 600 rounds over the crowd’s heads. In another instance, in early March, harassing fire was directed from about 300 metres at a section from B Company near Batugade. Fire was not returned as the soldiers could not see the muzzle flashes through the thick forest. Several small groups of the militia also infiltrated across the border prompting Gould to despatch patrols in pursuit—although the militia managed to elude them.15

Acknowledging the benefits of deploying mechanised infantry in such operations, Gould observed that ‘the mech[anised] battalion is more capable in a peace-support environment than a standard battalion’, echoing similar comments made by Murray Blake when he was commanding 5/7 RAR 22 years earlier. Gould argued that ‘we have our own organic mobility and we use that mobility, in this AO particularly, to be everywhere all the time’. Coupled with the range of communications and the new Battlefield Command Support System fitted to the M113, the ‘40 very strong rifle-section commanders’ in the unit provided the ‘flexibility, adaptability and good sense to respond proportionately’.16

Reflecting the validity of Gould’s assertions, subsequent battalion rotations were provided with nearly 30 armoured vehicles in the armoured group, with ASLAVs and M113 APCs in support, as well as a ten-man detachment to operate the Coyote surveillance suite loaned by Canada. That group provided the successive Australian battalions (AUSBATTs) with a range of options and reliable assets capable of reaction over the majority of the AO, regardless of weather conditions.

The tour of 5/7 RAR in East Timor straddled the changeover from INTERFET to UNTAET, and between April 2000, when it returned to Australia, and June 2004, by which time battalions of the regiment had completed eight tours of duty in East Timor, each of about six to seven months.

6 RAR in East Timor, April to October 2000

6 RAR as AUSBATT II, under Lieutenant Colonel Mick Moon, took over 5/7 RAR’s area of operations on 25 April 2000. In preparing for deployment 6 RAR had received about 200 General Reserve soldiers on fifteen months’ full-time service from reserve battalions in Western Australia, Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania and Queensland. To prepare the battalion for its rotation Moon had been allocated four months to do what had taken his predecessor, Lieutenant Colonel Colin Townsend, twelve months to achieve before 6 RAR deployed to Vietnam in 1966.17

Following a fairly quiet period during the tail end of 5/7 RAR’s tour of duty, another quiet period was not an unreasonable expectation. But Moon’s rigorous pre-deployment training regime would prove invaluable. Moon also implemented a very active patrolling program, following the practice of his former commanding officer in Somalia, Lieutenant Colonel David Hurley, who stated ‘when in doubt, patrol’.18 As it turned out, 6 RAR saw the most number of contacts and militia activity of any battalion under UNTAET. Conscious of the tight rules of engagement mandated for UNTAET’s forces, the militia had developed tactics to exploit the constraints imposed, such as using grenades and small arms fire at night and having the lead man in a militia patrol travel unarmed, with the remainder following behind remaining armed in order to deceive UNTAET troops.

Four incidents stand out during this period. The first was a grenade attack at Nunura Bridge on 28 May 2000, resulting in Lance Corporal Wayne Harwood being injured from a grenade explosion. The second incident took place in June 2000, in Major John McCaffery’s area of operations, shortly after his B Company had taken over responsibility for the area from D Company. This incident involved a night-time militia attack on Corporal David Hawkins’s section post at Aidabasalala. Hawkins, a veteran of Somalia and Rwanda, had hastily sandbagged and screened his post under McCaffery’s instructions only hours prior. Hawkins led his section of mostly reservist soldiers with restraint in the face of a surprise attack that included six grenades thrown at the post (one of which exploded in the empty sleeping bag of a man on piquet) and several magazines of small arms ammunition fired from a second firing point before the militia withdrew. In recognition of his fortitude and discipline under fire, Hawkins was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross. The third incident occurred close to the border near Suai on 23 July when militiamen opened fire and killed a soldier of a New Zealand tracking team, Private Leonard Manning. His body was recovered the next day, having been mutilated. There were feelings of anger, apprehension and revulsion following this incident, and attitudes hardened against the militia. The fourth incident occurred on 2 August 2000 and involved five to six militia members walking into an Australian patrol that had temporarily halted for lunch. The militia group was engaged with machine-gun fire from Lance Corporal Brad Wilkins, who had been watching their advance towards his position. The machine-gun fire killed two militiamen, and the platoon commander, Lieutenant Mike Humphries, aggressively pursued the fleeing militia—he was later awarded a Distinguished Service Medal for his role in this action. A few days later, a tragic accident occurred in the battalion’s AO, when Corporal Stuart Jones died from gunshot wounds from his rifle, which accidentally discharged while he was riding in an ASLAV.19

By the time the 6 RAR Battalion Group completed its tour, they had killed or wounded seven infiltrators. They had also deterred many others from infiltrating into, and through, the Bobonaro district. In addition, they had experienced some close calls.20

1 RAR in East Timor, October 2000 to April 2001

On 25 October 2000, 6 RAR handed over responsibility for an area of 1138 square kilometres along the northern border region of East Timor that had become known as AO Matilda to AUSBATT III, 1 RAR. Having just been replaced as the ready battalion group prior to INTERFET in 1999, the soldiers of 1 RAR were eager to make up for the opportunity they had narrowly missed out on earlier. Conscious of the challenges that 6 RAR had faced, 1 RAR, under Lieutenant Colonel John Caligari, also adopted a robust posture of patrolling to deny militia access into East Timor across the Tactical Coordination Line (TCL). This posture proved the correct one. In December 2000, for instance, a station established near Balibo to prevent infiltration and exfiltration was fired upon by militia. Operation Valiant was launched in response using A Company, under Major Jamie Patten-Richens, to establish a covert stationary blocking force and overt patrols intended to drive the militia toward the blocking force. The tactic worked, resulting in the death of a militia member on the operation’s first day with no loss or injury to the platoon involved: 3 Platoon, A Company, under Lieutenant Steve Thorpe. The section commander concerned, Corporal Jonathan Griffiths, was a veteran of 1 RAR’s tour of duty in Somalia seven years prior. Caligari subsequently praised Griffiths for acting decisively and engaging effectively. Notwithstanding their fine performance, Thorpe and Griffiths faced a thorough and unsettling investigation by Dili-based staff officers, which, in the end, validated the actions they had taken.21

Such dispersed actions did not prove unusual as the size of the AO and the nature of the tasks meant that the battalion group was spread widely. To command such a dispersed group effectively, Caligari avoided being anchored to his headquarters and delegated responsibility for running his headquarters to the battalion second-in- command, Major Steve Ferndale. Like Moon before him, Caligari’s approach was influenced by his experience working for Hurley with 1 RAR in Somalia in 1993. Hurley, lacking integral aviation support and burdened with a large number of administrative, governance and reporting tasks, had been effectively prevented from getting out to visit his troops on operations. With Ferndale performing many of the administrative and reporting functions, Caligari was free to be in the field on operations.22

1 RAR’s largest event was Operation Diamantina, a battalion cordon and search conducted on 15 April 2001. To the delight of people such as the battalion operations officer, Major Mick Mumford, this operation involved the deployment of the battalion tactical headquarters for the first time on the battalion’s tour. The deployment included over 300 soldiers, two Kiowa reconnaissance helicopters, 27 armoured vehicles, 23 civilian police and other UNTAET agencies operating in and around the village of Tonobibi.23 Hand in hand with such operations, the efforts of the civil military affairs team were maximised as well, along with the humanitarian assistance actions, known as ‘WHAM’ Patrols, aimed at winning hearts and minds. The end result was the confiscation of contraband as well as some minor weapons and military equipment. When the search was complete, the commander, Sector West, Brigadier Ken Gillespie, wrote to Caligari that ‘the operation was successful by any measure and I was very happy with the attitude and professionalism displayed by your officers and men’.24 To Caligari, there were other memorable aspects as well. For instance, ‘the malaria trial we conducted (tefenequine) resulting in zero malaria (the only battalion to achieve this)’; and ‘the special relationship I had with [the commanding officer of ] 131 Agung given his good English and friendship with Glen Babington from [his] time at Indonesian Staff College’.25

One of the most remote places that soldiers on most rotations passed time at was ‘Retransmission Site 1’ on ‘Everest’, the high peak that served as a key commu nications link across the rugged terrain along the border area. Everest had commanding panoramic views deep into Indonesian West Timor and, to the north, the beaches along what the soldiers aptly called ‘the Mosquito Coast’. The site consisted of three medium-sized tents and two large tarpaulins under which stores were kept. Access was usually by Black Hawk helicopter with teams taking weeklong turns at providing security for the site. However, because Everest was frequently cloud shrouded and exposed to strong winds and heavy rains, soldiers often found themselves staying there several days longer than originally intended.26

4 RAR in East Timor, April to October 2001

One unit particularly capable of responding flexibly to challenges was 4 RAR. When notified to replace 1 RAR in East Timor, 4 RAR had not long previously been raised as a commando battalion, developing special forces capabilities to supplement those of the SAS. With the commitment to East Timor continuing, however, 4 RAR was re-roled as a light infantry battalion for deployment to East Timor as AUSBATT IV. This involved reorganising from the existing two commando-companies structure to a light infantry model with four companies and a growth in the unit from 220 to 670 personnel. With attachments, that number would grow to 1100. Under Lieutenant Colonel Jeff Sengelman, 4 RAR took control of AO Matilda on ANZAC Day 2001 in the presence of the Governor-General, Sir William Deane. 27

The first task was to establish a genuine security partnership with the East Timorese and the battalion strongly emphasised languages, maintaining relationships established by previous battalions as well as using new technologies. This ‘intelligence-led’ but people-focused approach saw the battalion group conduct the majority of its operations in close proximity to the TCL. This approach was in contrast to earlier AUSBATT rotations that had to contend with challenges further inside East Timor. The focus on the border itself was warranted because of the number of incidents that took place there. These included a TCL violation on 5 May 2001 intercepted by Corporal J.C. Whitebread and his section from D Company. Other incidents involved an outbreak of violence involving a grenade attack by militia members at the Maubasa markets on 29 May (with several fatalities and about 50 people wounded) and shallow cross-border militia raids in June, including an attack on an A Company patrol led by Corporal K.T. Campbell.28

Thankfully, the focused operational approach, based on good intelligence and

A patrol from D Company, 4 RAR in the East Timorese border town of Memo in the days before the new nation’s first elections on 30 October 2001. 4 RAR had reorganised from the commando role it had been given in order to provide a ‘traditional’ battalion for its tour of East Timor (Department of Defence photo no. EM107).

enhanced cooperation with the local East Timorese, enabled the battalion to provide timely responses to warnings of impending incidents. With parliamentary elections scheduled, several operations were launched in the lead-up period through August 2001 to prevent militia disruption. With the onset of the elections, Operation Fullback was launched as an AO-wide deployment from 27 August to 9 September. Troops were pre-positioned in strategic locations including polling booths across the AO, supplemented with forces on stand-by ready to react in support of the police. The battalion group’s efforts helped ensure that the election took place without any security concerns and over 95 per cent of the registered electorate voted on election day. By the end of 4 RAR’s tour there were clear signs that stability was returning to East Timor, not the least of which was the peaceful resettlement of over 5000 refugees and more than 700 former militia in AO Matilda.29 Addressing the battalion Sengelman observed that ‘when they see us they smile. When we drive by, they wave and despite our rifles, the children run to be near us when we enter their villages. It’s this sincere and heartfelt trust in who you are, what you have done and ultimately represented which draws them so willingly in friendship.’30

In pursuing this approach, a particularly useful adjunct to the battalion group during this period was the four-man military information support team, tasked with providing public information and information operations support. The team provided this support through the provision of printed products—including a weekly news-sheet, posters and leaflets—and by loudspeaker broadcasts, the gift of novelty products and by personal interaction with locals. Indeed, the information support team had deployed with INTERFET and would remain an important component of the AUSBATTs for the remaining rotations also.

2 RAR’s Return to East Timor, 2001–02

As AUSBATT V, 2 RAR deployed to the Bobonaro district of East Timor from October 2001 to April 2002. Lieutenant Colonel Angus Campbell, commander of 2 RAR, claimed his battalion’s tour of duty ‘was the high water mark of Australia’s contribution’ to UNTAET. In providing a synopsis of activities during their tour of duty, Campbell stated that the 2 RAR battalion group continued conducting ‘ongoing and arduous patrol operations’. In addition, it ‘overcame challenges of the wet season, moved the headquarters from Balibo to Moleana, guaranteed the safety of reconciliation and refugee operations, facilitated development assistance to local and isolated communities, rebuilt most of AUSBATT’s forward operating bases, maintained the road system and provided security and logistic support to the presidential elections—to mention only some of our tasks.’ Campbell thus argued that ‘upon our handover to the 3rd Battalion Group, some two years since the successful INTERFET operation and the creation of UNTAET, the staged draw-down of forces commenced’.31

One returning soldier, Sergeant Paul Smedley, captured the feelings of many who returned after having served with INTERFET. ‘We all soon realised just how things had changed. We now had new buildings, showers, flushing toilets, air con and much, much more. The job seemed so much easier from Peace Enforcement to Peacekeeping. Whilst living conditions have greatly improved, some things will never change for an infantry soldier: the large and heavy packs, big hills, ration packs, a lack of resources and a great deal more.’32

Given the nature of the deployment, the battalion’s Support Company was re-roled as the Reconnaissance and Surveillance Company, incorporating the Mortar Platoon as the aviation security platoon, the Signals Platoon, as well as the Reconnaissance Platoon with its four patrols. Additionally, the Sniper Platoon provided the immediate reaction force that could be transported by Black Hawk, ASLAV or APC. The company also worked closely with the radar and thermal imagery capabilities from 131st Locating Battery, as well as the tracker dogs from the military police and RAAF dog sections.33 These same capabilities were also available to 2 RAR’s successor battalion, 3 RAR.

3 RAR Returns to East Timor, 2002

3 RAR, under Lieutenant Colonel Quentin Flowers, returned to East Timor as AUSBATT VI, taking over from 2 RAR in April 2002 during the dry season. East Timor became self-governing during this period. This was an event that not only created widespread celebrations for the Timorese people, but also induced a sense of achievement for AUSBATT members. During the six months’ deployment, the four companies of the battalion worked within two different areas of operations, enabling members to broaden their experiences.34

For all battalions the repetitive nature of many of their tasks meant the vernacular term, ‘ground hog day’, was used frequently to describe their experiences.35 For some, billycart races were the distraction of choice. For others, it was playing Gameboy or trying to teach locals some English, attending the ever-popular ‘Tour de Force’ concerts arranged by the Forces Advisory Committee on Entertainment, occasionally having a swim at the beach, taking part in inter-unit sports matches or playing harmless pranks on each other. With the establishment of telephone services and internet terminals, contact with loved ones at home became easier over time as well, particularly as the force became more established.36

5/7 RAR Returns to East Timor, 2002–03

5/7 RAR deployed for the second time, once again following on from 3 RAR. This time, however, the battalion deployed under the mandate of the United Nations Mission in Support of East Timor (UNMISET) in October 2002 as AUSBATT VII, under Lieutenant Colonel Mick Tucker. Their assigned area remained AO Matilda in the north-western corner of the country. A company-strength general reserve force deployed as part of the battalion. The selection process followed a 90-day selection phase involving volunteer soldiers from 8/7th and 5/6th Battalions, the Royal Victorian Regiment, as well as from 2/17th and 41st Battalions, the Royal New South Wales Regiment. On completion, the soldiers were re-badged with RAR badges at a beret parade with the Chief of Army, Lieutenant General Peter Leahy, in attendance.37

The battalion group included the range of attached elements, as with the previous AUSBATTs, including the battalion engineer group that incorporated a field engineer troop with a trade section and plant section, support troop and a forward repair team. Given the nature of tasks and the engineers’ virtually permanent association with the battalion group, the assault pioneer platoon was grouped with the engineer group as well.38 The engineer group proved to be fundamental to the effectiveness of the successive AUSBATTs. For instance, the engineers and sappers were instrumental in improving the living standards at all operating bases, and were responsible for the increase in physical security through the construction of protective works. In addition, their road maintenance work enhanced the battalion’s freedom of manoeuvre.39

While the situation in East Timor was becoming routine and relatively benign there were still sporadic incidents. For instance, 5/7 RAR had to respond during their tour when a milita group crossed from West to East Timor and attacked civilians. The battalion conducted a massive search operation during which the Royal Fiji Military Forces (RFMF) company attached to 5/7 RAR captured the militia group—an incident that caused Australian and United Nations planners to defer their plan to downsize the size of the AUSBATT VIII.40

1 RAR Returns to East Timor, 2003

Under these circumstances, 1 RAR, under Lieutenant Colonel Stuart L. Smith, redeployed to East Timor taking over as AUSBATT VIII between 7 and 17 May 2003. Smith’s force was built around three infantry rifle companies and a range of attachments from 3rd Brigade. The force spent the next six months watching, patrolling, liaising, building and sustaining. During Operation Marson,41 for instance, the battalion established patrol bases in the major district population centres and conducted regular vehicle and foot patrols in the local villages and along the TCL. During Operation Badcoe,42 the civil–military cooperation (CIMIC) teams operating as part of the battalion group established border agencies coordination meetings and provided training, liaison and support to the Timor Police border patrol unit at border junction points. Operation Cosgrove,43 a combined APC and infantry operation in June 2003, provided liaison and security along the TCL for a joint Indonesian–Timor Leste government survey team to map the official border between the two countries. Operation Macgregor,44 in August 2003, involved CIMIC teams and engineers developing the infrastructure in each district, with a focus on promoting community aid projects, constructing schools, repairing roadways and refurbishing market buildings. In October 2003, 1 RAR also assumed responsibility for the Oecussi district.45

According to Smith, the battalion group benefited greatly from the fact that many of the corporals and sergeants had deployed previously to Timor as junior soldiers. Their experience proved essential for the battalion’s success in dealing with an operational environment that was now more complex than before because of increased civil and military interaction. On any day a corporal patrol commander was expected to deal with civilians, aid agencies and a variety of security forces. On 19 September 2003, for instance, a rifle section from C Company responded to an incident on the TCL where a West Timorese was shot dead by the East Timorese police. The section commander was required to adjudicate a tense stand-off between angry civilians, aggressive Indonesian police, East Timorese police, UN observers and TNI. He relied on his experience and training to deal with this strategically sensitive matter in a neutral manner and his timely actions were recognised by a UNMISET Force Commander’s commendation.46

6 RAR Returns to East Timor for the last AUSBATT

Following 1 RAR, in November 2003, 6 RAR returned to East Timor as the last AUSBATT, initially under Lieutenant Colonel Glen Babington and, from early in 2004, under Lieutenant Colonel Shane Caughey. The threat was less than previously, but a two-thirds’ reduction in the number of troops deployed combined with a threefold expansion of the area of operations kept the task challenging for the battalion. In addition to AO Matilda (the Bobonaro district), the Australian area of operations encompassed the Liquica, Ermera, Ainaro, Cova Lima and Oecussi districts, with a population of approximately 403,000. This area covered the entire length of the TCL delineating the border between East Timor and Indonesia. In other words, two rifle companies were required to cover an area that had previously been covered by three full battalions. In addition, this was to be the longest rotation of Operation Citadel, with the first troops arriving in October 2003 and the last to leave in June 2004.47

Caughey, who took command of AUSBATT IX in January 2004, observed that ‘the challenges of maintaining operational capability versus the administrative pressure to draw down early to meet end of mission time lines required careful management and some good lessons were learnt’. For instance, in order to maximise operational experience and share the load, the rifle companies were rotated on a three-month basis. D Company deployed first, followed by C and then A Company. Other force elements followed similar rotation plans, with a select few remaining in East Timor for the duration of the battalion’s tour of duty. The draw-down in numbers also led to the incorporation of a Fijian infantry company into the battalion group. The international flavour and the increased area of responsibility led to the redesignation of the battalion group from AUSBATT to WESTBATT. Yet to maintain coverage of such a large area, the standard attached elements from other units remained crucial to the effective function of the force. 48

With its expanded area of operations, three forward operating bases were specially constructed: a permanent one at Moleana, and temporary locations at Aidabaleten and Gleno. These bases were used for ‘green hat’ patrols (that were associated with stealthier surveillance tasks) and ‘blue hat’ patrols (that involved chatting with locals). Indeed, the range of responsibilities and the array of potential threats in East Timor meant that soldiers were required to be just as perceptive, responsive and flexible as those deployed on other operations. Supporting the local security agencies was the main emphasis for these patrols. The Border Patrol Unit and the Timor Leste police force were the primary focus as these agencies were to become responsible for security in the western region once WESTBATT departed. WESTBATT also provided training advice to the Timor Leste Defence Force while also working closely with UNMISET agencies, including the UN police and military observers. In the end, however, some of the hardest work involved preparing to extract the force from an area where Australian troops had been on operations for nearly five years.49

East Timor overview

Operations in East Timor from 1999 to 2004 had a significant impact on the battalions of the RAR. For the first time since the Vietnam War, all the active battalions had taken turns on deployment and the wealth of experience gained gave the RAR and the wider army a new lease on life. The operational imperatives saw the hastened introduction into service of critical new equipment that significantly enhanced the capabilities of individual soldiers, the battalion as a unit, as well as for the wider combined-arms team. Particular benefit was gained from working with otherwise rarely deployed assets such as the military information support teams, the geomatic, special communications, human intelligence, media and civil affairs teams, as well as the medical and aviation assets and engineer support elements. This experience reinforced many of the lessons of counterinsurgency operations from the Vietnam War era and helped refine tactics, techniques and procedures. The experience also provided a proving ground for the soldiers and commanders of the army. That experience would prove invaluable on other operations both far afield and closer to home in places such as the Solomon Islands and again in East Timor in 2006.

Two years after the withdrawal of 6 RAR from what had become known as Timor Leste, the security situation deteriorated dramatically following the sacking of several hundred soldiers from western East Timor. ADF units were pre-positioned for a rapid response in mid-May 2006 in anticipation of a possible breakdown of law and order. As part of the newly christened Operation Astute, units of the regiment were once again called on to deploy at short notice to Dili.

The Australian deployment to Timor Leste followed the receipt of a formal request for military assistance to the Australian government late on 24 May 2006. Following the immediate approval of this request, the Vice Chief of the Defence Force, Lieutenant General Ken Gillespie, travelled to Timor Leste on the next day to negotiate the terms and conditions of the ADF deployment. The ADF’s mission was specified as being ‘to assist the Government of Timor-Leste to facilitate the evacuation of Australian and other foreign nationals as is appropriate and necessary; stabilise the situation and facilitate the concentration of the various conflicting groups into safe and secure locations; and create a secure environment for the conduct of a successful dialogue to resolve the current crisis’.50

As the negotiations for the mission were taking place, a company from 4 RAR (Commando), as the forward element of the Australian force, secured the Comoro

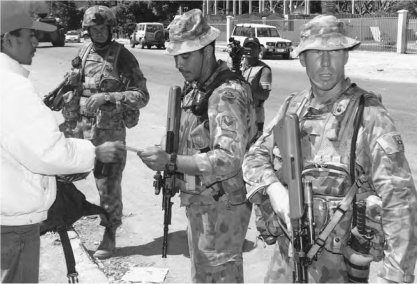

Corporal Antonio Goncalues (centre) of D Company, 3 RAR checks the identification of a local man in Dili in May 2006 upon the return of the regiment to East Timor (Timor Leste) as part of Operation Astute (Department of Defence photo no. 20060530adf8161479_097).

airfield in order to enable the follow-on force to establish a presence in Dili before fanning out across the city. Brigadier Michael Slater, Commander 3rd Brigade, was appointed commander of all Australian forces in Timor Leste. Slater, who had commanded 2 RAR during the initial INTERFET deployment, faced a challenging and more complicated situation than he had in 1999. This time the threat was harder to identify and contain as local police and soldiers had taken to fighting each other. Even when these forces were contained armed gangs roamed the streets, making it particularly challenging for the Australian forces to restore security without the use of lethal force. The problem was compounded by murky local political wrangling of which the Australians, at first at least, had only a limited understanding.

The force at Slater’s disposal included a strong Australian presence in and around Dili with around 1300 ground troops conducting security operations, supported by 500 Malaysian troops and a company of New Zealand infantry. The Australian contribution consisted of an infantry battalion group, based on 3 RAR under Lieutenant Colonel Mick Mumford, who had served as the 1 RAR operations officer with UNTAET in 2000 to 2001. The force deployed with two companies from 2 RAR and one from 1 RAR as well as a commando company group from 4 RAR and ‘G’ Company—re-roled gunners from the 4th Field Regiment. Support was provided by Black Hawks from the 5th Aviation Regiment as well as the RAAF (including airfield defence guards), and RAN support from all the fleet’s amphibious ships (HMA Ships Manoora, Kanimbla and Tobruk).51 The breakdown in law and order faced by Slater’s force was indicative of deep-seated problems within the fledgling nation which would not be addressed in one six-month deployment. It was soon evident in East Timor, Canberra and in UN headquarters in New York that Australian military engagement would be required for an extended period.

With a longer term mission in mind, the Australian government committed to maintaining a ‘green helmet’ force, under direct Australian rather than UN control, to assist the East Timorese to restore stability. Colonel Mal Rerden was selected as the officer to command the follow-on force and later deployed as Slater’s deputy commander. On the completion of Slater’s term and as the Australian force was being drawn down to near 800 personnel in late 2006, Rerden was promoted to brigadier and command of the residual force, based around the recently deployed 6 RAR, under Lieutenant Colonel Scott Goddard. Goddard’s battalion group included a rifle company from 1 RAR as well as another G Company—a re-roled battery from the 16th Air Defence Regiment. By the end of 2006, 6 RAR was working closely with UN police elements moving towards a handover of responsibilities to the Timor Leste Defence Force, and the Timorese police. But with elections scheduled for mid-2007 and several problems that contributed to the May breakdown left unresolved, the force’s work remained incomplete at the end of 2006. In the meantime, the deterioration of the situation in Dili in May 2006 had occurred only shortly after a crisis had emerged in the Solomon Islands, but problems there had been exercising Australian military minds for some time.

Table 15.1: East Timor infantry battalion/battalion group rotations

(CO in brackets)

| Deployments 1999–2004 | |

| 20 September 1999 | 2 RAR (Slater) deploys to Dili |

| 21 September 1999 | 3 RAR (Welch/Singh) deploys to Dili |

| 4 October 1999 | 5/7 RAR (Gould) deploys to Dili (AUSBATT from |

| Feb 2000) | |

| January 2000 | 2 RAR (Gould) returns to Townsville |

| February 2000 | 3 RAR (Singh) returns to Sydney |

| April 2000 | 6 RAR (Moon), AUSBATT II to replace 5/7 RAR |

| October 2000 | 1 RAR (Caligari), AUSBATT III to replace 6 RAR |

| April 2001 | 4 RAR (Sengelman), AUSBATT IV to replace 1 RAR |

| October 2001 | 2 RAR (Campbell), AUSBATT V to replace 4 RAR |

| April 2002 | 3 RAR (Flowers), AUSBATT VI to replace 2 RAR |

| October 2002 | 5/7 RAR (Lean/Tucker), AUSBATT VII to replace 3 RAR |

| May 2003 | 1 RAR (Smith), AUSBATT VIII to replace 5/7 RAR |

| November 2003 | 6 RAR (Babington/Caughey), AUSBATT IX to replace |

| 1 RAR | |

| June 2004 | 6 RAR (Caughey) returns to Brisbane |

| Operation Astute, 2006– | |

| May 2006 | 3 RAR (Mumford), with companies from 1, 2 and 4 RAR |

| (Cdo), and 4 Fd Regt | |

| November 2006 | 6 RAR (Goddard), including companies from 1 RAR and |

| 16 AD Regt, with a platoon from 4 RAR (Cdo) |

While East Timor had stolen the regional limelight, particularly in 1999 and 2000, developments in the Solomon Islands drew considerable attention as the security situation deteriorated. The signing of the Townsville Peace Agreement in October 2000 led to the deployment of the unarmed International Peace Monitoring team between October 2000 and June 2002. The ADF contribution, as part of Operation Plumbob, was led by 1 RAR under Lieutenant Colonel John Caligari. Caligari’s operations officer, Andrew Gallaway, recalled that ‘on that trip we sailed on HMAS Manoora for its first operational voyage. Major Pete Connolly was OC C Company (RCG). The RSM, WO1 Steve Ward, also accompanied the CO on this trip.’ Caligari recalled that ‘it took us out of our battalion exercise and offshore for 3 weeks’. He further observed that the raison d’être for the 1 RAR group being left behind when 3rd Brigade deployed in late 1999 finally came to pass.52 By early 2003, however, the situation had once again deteriorated and the former police commissioner, Sir Fred Soaki, was assassinated in February. The Solomon Islands were in a parlous, weak and vulnerable condition by mid-2003 when pressure mounted for outside assistance to be provided. By July the Solomons’ Prime Minister requested a ‘strengthened assistance’ mission from the Australian Prime Minister. In July the then online battalion of the Ready Deployment Force, 2 RAR, under Lieutenant Colonel John Frewen, was warned for service in the Solomon Islands. The response by Australia and its regional partners was called the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI), the military support of which was Operation Anode.53

On 24 July 2003 over half of 2 RAR deployed with RAMSI as the nucleus of Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF) 635.54 This force included four rifle companies— one each from Australia, New Zealand and Fiji and a composite company from Australia, based on D Company 2 RAR with platoons from Tonga and Papua New Guinea. Frewen added ‘we have also had most of Support and Admin Companies from 2 RAR here at various stages’.55 CJTF 635 was a unique organisation that reflected the increased complexity of modern operations. It included 1800 military personnel from five nations, with maritime and air elements under command of Frewen’s battalion headquarters, including the entire New Zealand contribution under full operational control from the outset. Australian air and maritime forces were initially only allocated as being ‘in support’ although they were eventually placed under operational control as well.56 RAMSI, or as it was known locally, Operation Helpem Fren, was exceptional in that it was preventative, breaking new ground in lowering the threshold for intervention in the indisputably internal affairs of a sovereign state to a degree not witnessed in international peacekeeping.57 RAMSI was created as a police-led mission, but one of the reasons that the Participating Police Force was able to do its work effectively was the cover provided by the large military force deployed with the police.58 As Special Coordinator, the diplomat (and later Secretary of Defence) Nick Warner observed, ‘we came in with a very large potent military force . . . We did that quite deliberately so that we didn’t have to use military force during this operation, and it worked.’59

The military force adopted a fairly low profile. They arrived in the Solomon Islands at dawn, deploying onto the infamous Second World War battle sites of Henderson Field by C–130 Hercules aircraft, and nearby Red Beach by landing craft and Sea King helicopters from the amphibious landing ship HMAS Manoora.60 Once deployed, the forces remained, for the most part, located in an old resort near the airport, unobservable from the road. This placement was in contrast to the buildings at the centre of town occupied, for instance, by the United Nations in Dili.61 Nevertheless the deployment ‘sent an unambiguous message of resolve to the local criminal elements and rendered resistance futile’. In fact, argued Frewen, ‘the use of military force in this instance was about messages and required subtle application. The substantial military presence, including land, air and sea assets, signalled to criminals and law-abiding citizens alike that the intervention in the Solomon Islands was to be taken seriously.’62

Soldiers from 2 RAR on patrol in the Solomon Islands in 2004 as part of the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands. Elements of the battalion had first deployed to the islands in mid-2003 with infantry from New Zealand, Fiji, Tonga and Papua New Guinea to make up the bulk of the land element of Combined Joint Task Force 635. The military aspects of this mission were generally kept low-key and were geared to support the police and other civilian agencies deployed (Department of Defence photo JPAU30 MAR04AB03).

A key part of the mission was reducing the prospect of further armed violence. There followed a three-week gun amnesty that drew in almost 4000 weapons, including 700 high-powered military weapons. Visiting police made over 360 arrests for serious crimes and sixteen police outposts were also established in all provinces. Essentially, Frewen argued, ‘a small war was taken off the streets without the use of financial inducements or force’. The high point, however, came with the celebrated arrest of ringleader Harold Keke, on 13 August, three weeks after the intervention commenced. Open days also proved effective. Through these events, noted Frewen, ‘we promoted awareness of our technological edge over potential adversaries’. This included the demonstration of night vision goggles, ground sensors and the tactical unmanned aerial vehicles that, Frewen observed, ‘were a potent psychological tool that clearly played on people’s minds’.63

When the main elements of 2 RAR departed in December 2003, leaving B Company, RAMSI was as popular as it was when it arrived. Testament, argued Frewen, ‘to the skilful and balanced execution of operations by commanders and all ranks throughout the deployment’. Until April 2004 all of 2 RAR’s companies participated on Operation Anode, whereupon a platoon from 5/7 RAR formed the Australian contribution to the Pacific Islands Company alongside soldiers from Tonga, PNG, Fiji and New Zealand to form the RAMSI quick response force.64

By late 2004 the situation in the Solomon Islands seemed sufficiently calm for a reduced military presence and CJTF 635 was reduced in size to a platoon of infantry from New Zealand working alongside an eleven-nation PPF. On 22 December, however, an Australian Federal Police Protective Services officer, Adam Dunning, was shot and killed while conducting a vehicle patrol with RAMSI. The 3rd Brigade ready company group was A Company, 1 RAR in Townsville, which was put on alert on the same day. The government quickly decided to support the reinforce ment of Operation Anode with the RCG, and within eighteen hours of the government’s decision, 100 men, vehicles and equipment arrived in the Solomon Islands by air.65

With 1 RAR’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Chris Field, appointed Commander CJTF 635, A Company, 1 RAR stayed in the Solomon Islands just over a month, until 25 January 2005, operating on the basis of three premises. First was the need to reinforce RAMSI. Second was the intention to enhance the security environment. This involved conducting over 300 tasks in support of the PPF, including foot and mobile patrols, supporting special response and investigative operations, conducting provincial patrols and providing a quick response to assist any high value search operations. The third premise was that the deployment was an effects-based operation, that is, it was geared to producing results.66

Conscious of the need to maintain a visible presence in the Solomon Islands, 3 RAR deployed a company to replace the soldiers from 1 RAR. 3 RAR’s deployment, however, was marred by the death of Private Jamie Clark, who was killed on patrol when he tragically fell down a mine shaft.67 Other battalions of the RAR also took their turn in the Solomon Islands, allowing many junior leaders to gain additional experience.

By April 2006, however, the military presence was becoming too small in a period of growing unrest. It was then, on 18 April, following riots in Honiara, that the ready company group, this time D Company, 1 RAR under Major Simon Moore-Wilton, was deployed to the Solomon Islands. The commanding officer of 1 RAR, Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Gallaway, convened a planning conference one hour after being warned for a possible deployment. His battalion was called in from a well-deserved stand-down after having helped clean up Innisfail after Cyclone Larry. With support from the brigade commander, Brigadier Mick Slater, and dedicated headquarters staff, pre-deployment preparations continued through the night and the force was ready to deploy by 0730 hours the next morning.68

Lieutenant Colonel Gallaway took command of CJTF 635. More soldiers from 3 RAR, as well as two Iroquois helicopters from the 5th Aviation Regiment, soon joined the soldiers from 1 RAR. Once on the ground, choke points, key points and the most dangerous trouble areas were patrolled and controlled in support of the PPF. To many, reported Captain Al Green, the friendly faces of Australian soldiers ‘was a reassuring sight to the residents who just wanted the violence to stop’.69 The views of Lance Corporal Charles Boag, second-in-command of 7 Section, captured much of the feelings of the soldiers deployed there. He said they enjoyed being deployed, even at short notice and the locals ‘were so happy to have us here’.70 Clearly, the Solomon Islands would remain a point of enduring concern, pointing to the need for continued Australian attention. Nonetheless, the responsiveness and capability of the units involved stood in stark contrast to the limited joint capability demonstrated following the Fiji coup in 1987, when a 1 RAR company was positioned on warships. In the meantime, the regiment had developed a range of other capabilities that further demonstrated its versatility and adaptability.

On return from Operation Tanager with UNTAET in East Timor, 4 RAR was restructured to the commando battalion organisation assumed in 1997. The rationale for raising 4 RAR had grown out, in part, of the difficulties experienced during the Fiji coup of 1987, which was, in the view of the former Commander Special Forces, Brigadier Jim Wallace, a ‘Keystone cops-like exercise’ that reflected the lack of training in amphibious operations and validated the raising of a regular force commando unit.71

Notwithstanding the improvements that had been made in amphibious operations in 1 RAR and 2 RAR since 1987, and the inherent capabilities of 3 RAR, 4 RAR returned to being a commando unit, with capabilities that complemented and augmented the SAS Regiment’s ability to conduct special operations. The battalion was designed to be a self-contained flexible force able to be deployed at short notice to undertake offensive operations in support of Australia’s national interests. The unit was structured for both domestic counter-terrorism and conventional operations, with Battalion Headquarters, Tactical Assault Group (TAG) East, two commando companies, a logistic support company, an operational support company and a signal squadron.72

The regiment had only a minor role in the US-led invasion of Iraq in March 2003 when 4 RAR was directed to deploy an element of about 40 troops as part of the special forces task group, which was based on a Special Air Service squadron. Initially 4 RAR was warned to plan for two responsibilities. The first was force protection at the task force forward operating base, and the second was the formation of an alert force in conjunction with US Army aircraft, including Chinook and Black Hawk helicopters. Following acclimatisation and familiarisation with some new equipment, the force element assumed their responsibilities with the commencement of hostilities. As the operation progressed, other tasks began to present themselves. Commando teams were required to provide security to humanitarian assistance missions and other security operations at short notice. For instance, the force element was tasked with providing ‘sensitive site exploitation’ at the Al Asaad air base after it had been captured and cleared by other coalition forces. Once Baghdad had been captured and the Australian ambassador had taken up residence, the 4 RAR force element was given initial responsibility for security tasks in Baghdad until replacements from 2 RAR arrived. Other responsibilities included convoy protection using the 6x6 wheeled special reconnaissance vehicles prior to the deployment of an ASLAV detachment from the 2nd Cavalry Regiment.73

Security Detachment Rotations, Baghdad

As the security situation deteriorated in Iraq following the capture of Baghdad, a combined organisation, which included an infantry platoon, was raised and deployed to Baghdad to form the Australian Security Detachment or SECDET. The initial SECDET, under command of Major Mick Birtles, consisted of personnel from 2 RAR, 2nd Cavalry Regiment, 1st Military Police Battalion and 3rd Combat Engineer Regiment. The SECDET took up residence near the city heart at a place called Al Karadah among a population still in shock over events surrounding the fall of Saddam. The short notice for deployment left no time for pre-deployment training as a unit. Nonetheless, the SECDET members quickly managed to work together smoothly. Vehicle checkpoints were established and Iraqi civilians were often detected with weapons carried without coalition authorisation. Managing this challenge required the display of calm, confidence and discipline. Foot and ASLAV-mounted patrols were carried out by the SECDET as well. Birtles observed that ‘soldiers patrolled with weapons poised, observing their arcs of responsibility, and if required, ready to return fire. They correctly employed field-craft skills so as not to make themselves a target.’ To Birtles, ‘this was the Australian way of conducting operations and the same basic principles applied just as well in the streets of Baghdad as they do in the jungle, desert or rolling plains.’74 Incidentally, with other parts of the unit in Solomon Islands, this was the first time an RAR battalion had formed bodies deployed in two theatres on opposite sides of the globe, running two operations at once.

The SECDET rotated on a six-monthly basis from May 2003 onwards, with the detachments shrinking and then expanding again as the threat grew in mid-2004. The increase was from three to twelve ASLAVs and a platoon-sized to a company-sized infantry force.

A contact occurred on 13 April 2004. According to Major Kahlil Fegan, OC A Company, 3 RAR and then the SECDET commander, ‘It involved a SECDET ASLAV engaging a mortar base plate that was in the process of firing a number of mortar rounds into the Green Zone. The base plate was neutralised with 25 mm fire. This was the first time the main armament from an Australian ASLAV had been fired in a contact. A very successful contact that directly contributed to enhancing security within the local area and the Green Zone.’75 On 25 October 2004, a bomb detonated as a three-vehicle ASLAV patrol drove by, wounding three 2nd Cavalry Regiment crewmen (one seriously), seriously damaging the ASLAVs as well as killing a number of Iraqi bystanders.76 On 19 January 2005, a vehicle rammed the barricades outside the SECDET’s headquarters and accommodation flats. The driver escaped and detonated a 500-pound bomb, wounding two soldiers in the blast and killing two Iraqi civilian bystanders. Cement barricades prevented the attack from being much worse. On 24 January a suspicious truck loaded with drums was parked outside the flats and the driver left the vehicle, refusing to obey orders from the troops. In accordance with the rules of engagement the suspicious Iraqi was shot. On inspection of the truck, a large amount of petrol was found loaded in the drums—enough for a large bomb. That Australia Day another convoy of three ASLAVs was hit— this time by a vehicle-borne improvised explosive device—while running between Baghdad airport and the Green Zone. Ten SECDET personnel were wounded (three seriously) and the three ASLAVs were damaged. As the officer commanding SECDET 6, Major Matt Silver observed, ‘all the incidents have shaken everyone up

Corporal Nathan Heckel (right) and Private Stewart Alpert (back to camera) of the sniper section, 6 RAR, serving with Security Detachment 7 in Baghdad, Iraq in August 2005. The members of the regiment, along with military police and ASLAVs and crew from the RAAC, were deployed to Baghdad to provide security for the Australian embassy and its associated personnel (Department of Defence photo no. 20050729adf8243116_618).

Table 15.2 Security Detachment (SECDET) Baghdad Rotations, Infantry

Components (OC in brackets)

| SECDET 1 | 5 Platoon B Company, 2 RAR May to Sep 2003 (Mick Birtles) |

| SECDET 2 | A Company, 2 RAR 2003 (Mark Horne) |

| SECDET 3 | A Company, 3 RAR 2004 (Kahlil Fegan) |

| SECDET 4 | 5/7 RAR 2004 (Chris Sampson) |

| SECDET 5 | 5/7 RAR 2004 (Spencer Norris) |

| SECDET 6 | A Company, 6 RAR 2004 (Matt Silver/ Steven Tetley) |

| SECDET 7 | C Company, 6 RAR 2004–05 (Paul O’Donnell) |

| SECDET 8 | B Company, 1 RAR 2005 (Malcolm Wells) |

| SECDET 9 | Support Company, 3 RAR 2005–06 (Kyle Tyrell) |

| SECDET 10 | A Company, 3 RAR 2006 (Terry Cook) |

a bit—the reality of being over here, the fact that it’s probably the most dangerous place in the world today’.77 Following the attacks, the Australian Representative Office and the SECDET relocated from the original site at Al Karadah to a more secure site at Camp Victory (Presidential Palace North) and within the International Zone (Green Zone).78

Operations in Iraq clearly demonstrated the particular value of being able to understand the situation by communicating with the locals, and as a result, several SECDET members attended the ADF School of Languages Basic Arabic Course. As Major Spencer Norris observed, these language-trained personnel ‘were essential in providing interaction with locals, from authorities such as the Iraqi Police Force, to children playing in the street’. Gaining the locals’ trust and earning their respect, observed Norris, ‘enabled the Australians to better provide security and increase force protection’.79

Force protection remained a major focus, but in April 2006 Australia’s run of good luck in Iraq ended abruptly with the tragic death of Private Jacob ‘Jake’ Kovco, a soldier who had deployed from 3 RAR as part of SECDET 9. Lieutenant Colonel Mick Mumford, commanding officer of 3 RAR, explained that ‘the death of Private Kovco has hit the battalion hard, especially following the death of Private Clark in the Solomon Islands last year and a non-military related death in the battalion a month ago’.80 Investigations were initiated to explain the circumstances of his death, as well as the unfortunate and widely publicised mishap with the delayed return of his body for burial in Australia and are still underway.

Forces in Southern Iraq

While circumstances proved challenging in Baghdad, pressure was mounting for an additional substantial Australian land force contribution in Iraq. With the imminent

MAP 12. Iraq areas of operations: 4 RAR was the first battalion of the regiment to deploy to the Middle East when it supported the SAS during its operations during the invasion of Iraq in March 2004. It subsequently took on the first security duties in Baghdad. This role was taken over by the various Security Detachments, which included, in order of rotation, elements of 2 RAR, 3 RAR, 5/7 RAR and 1 RAR. In the country’s south the Al Muthanna Task Group (ATMG) deployed in 2005, where elements from 5/7 RAR and 2 RAR then served. In September 2006 ATMG’s title was changed to Overwatch Battle Group (West) when it took on the role of supporting Iraqi control of Dhi Qar province, a task it had already taken on in Al Muthanna that July.

withdrawal of the Dutch from southern Iraq in mid-2003, Prime Minister Howard announced the additional force commitment in February 2005. Members of B Company, 5/7 RAR were advised that in eight weeks’ time they would deploy with the Al Muthanna Task Group (AMTG), led by the 2nd Cavalry Regiment, to the province of Al Muthanna in southern Iraq. B Company, under Major Mick Garraway, formed Combat Team Tiger, the infantry combat team in the AMTG Battle Group, with a company headquarters, two rifle platoons, a cavalry troop, a reconnaissance patrol and a sniper pair. An infantry platoon was also included as part of Combat Team Eagle, the cavalry combat team. Coined Task Force Eagle, the AMTG, with its 40 ASLAVs, joined a British battle group commanded by a British Army colonel and accommodated in Camp Smitty, the forward operating base built just outside of As Samawah. This would be the first time units of the RAR had served on operations under British command since Confrontation in Borneo in 1965.81

The initial focus for operations was to augment the security of the Japanese Iraqi Reconstruction Support Group (JIRSG), and to provide security to Camp Smitty.

This involved establishing routines and procedures for the manning of guard towers and the front gate as well as work aimed at further developing the camp’s existing security measures. In support of the Japanese, mounted and dismounted patrols were conducted in combination with the use of observation posts. Of concern was the threat of vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIED), which, although not prevalent in Al Muthanna, was always a threat. Of more immediate concern, however, was the threat from stand-off attacks using mortars or rockets as the majority of attacks prior to the AMTG’s arrival were of this nature.82

To minimise the threat from such potential attacks an active patrolling program was put in place. Used in conjunction with the latest night fighting equipment and recently introduced personal role radios, the patrols were able to exercise an unprecedented level of influence in the province. The effectiveness of such patrols was also enhanced by the use of interpreters and the dissemination of information leaflets that helped build rapport with the locals. Stemming from the motorisation trials of the 1990s the army’s recently acquired Bushmaster armoured vehicles were rushed into service to provide improved levels of infantry protection, mobility, communications and comfort. Used in conjunction with the ASLAVs, the Bushmaster-mounted patrols provided the AMTG with great flexibility to respond to issues as they arose.83 Indeed, as the commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel Roger Noble observed, ‘the key aspect of AMTG was integration of combined arms at the lowest level. Infantry “bricks” (4 men) operating with 3x ASLAV—cavalry patrols as the basic tactical unit [sic]. There was no independent employment of either arm.’84

The city of As Samawah, near the AMTG’s base, remained fairly quiet but occasional incidents occurred. In fact, as Noble recalled, ‘There were 7 deliberate enemy actions against the Coalition in Al Muthanna during our tour.’85 On 12 October 2005, for instance, an AMTG patrol mounted in ASLAVs was conducting a routine security run through the outskirts of As Samawah just before midnight when the vehicle was fired upon. Two armed insurgents were seen running from the area, but the ASLAVs broke contact and did not return fire—no damage or casualties resulted.86

As the need became clear to form a second rotation of the AMTG, 5/7 RAR, under Lieutenant Colonel Peter Short, was selected in May 2005 to form the basis for the 450-personnel group. As with AMTG I, the second rotation, which deployed during the period from late October to early November 2005, consisted of a headquarters, two combat teams, a training team, an operational support squadron and a wide variety of specialist capabilities. The combat teams were based around C Company, 5/7 RAR and A Squadron, 2nd Cavalry Regiment. Preparation culminated in a mission rehearsal exercise with the various components under the task group headquarters’ command. That rehearsal was just as well, because the battalion received a substantial amount of new equipment in preparation for the deployment, including the remote weapon station mounted on the personnel carrier variant of the ASLAVs, automatic grenade launchers, Javelin medium range direct fire weapon system, thermal weapon sights, ‘surefire’ torches, and the Australian developed off-axis viewing devices for infantry small arms. Other new items included the multiband inter/intra team radio and tactical satellite communications systems, as well as new helmets, body armour and chest webbing. Additional intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance elements were also attached to the group.87

The Skylark miniature unmanned aerial vehicle (MUAV), for instance, proved particularly versatile in supporting patrols and base security. Lieutenant Colonel Short was full of praise for the MUAVs supplied by 131 Surveillance and Target Acquisition (STA) Battery of 20 STA Regiment, saying ‘it is an excellent capability and I could not imagine deploying without a UAV capability again’.88 Reflecting on the versatility of his battalion, Colonel Short observed that ‘5/7 RAR can operate at the higher end of conventional warfare as Battle Group Tiger’. Conversely, ‘the battalion can deploy to complex, non-conventional environments including peace support operations as demonstrated recently in Iraq’.89