Warrant Officer Class 1 Brian Betts (from the 1990 edition)

It all started for me when a letter arrived at my home in Sydney stating, ‘You are to report to Rushcutter’s Bay Recruiting Depot at 10 am 12 December 1953’. I had waited for about a month for this to arrive, ever since I had completed my national service commitment. On arrival at Rushcutter’s Bay, complete with cut lunch and shaving gear, I found I was waiting with two other nervous young men, one for the army and one intending to go into the navy. I hope that Tex has forgiven me after all of these years for talking him into joining the army instead.

After a medical, and filling in a number of forms, we were sworn in as part of the Australian Army, placed in a truck, driven to Marrickville personnel depot and issued with our uniforms. Because two of us were ex-national servicemen, we were placed on the next night’s guard roster. We were waiting until a group marched out of Kapooka to form a platoon for training at 4 RAR (the reinforcement battalion).

The beginning of the new year, 1954, started with a trip to Ingleburn to join up with the platoon with which we were to commence training. And what a platoon it was, a mixture of raw young men like myself, others coming into the infantry corps from other corps, and ex-diggers from the Second World War, all wanting to serve in Korea. At our first briefing, the company commander, Arch Dennis, asked the assembled group if anyone had had previous rank. I knew a few were ex-corporals and sergeants and even one was an ex-warrant officer, but not one hand was put up. Then up crept one. ‘OK, son, what rank were you?’ barked Arch. ‘I was a lance corporal in national service, sir,’ was the reply. Arch looked him up and down and explained to all what a disgusting rank it was. Thus our training started. We learned all about infantry tactics at section and platoon level, all about infantry weapons (Bren, rifle, 2-inch mortar, Owen gun, etc), and we were marched out to Green Hills from Ingleburn to learn to dig holes at Little Korea for a week or two at a time.

During this time we were a rather mixed bag: corps converts, UK enlistees and of course regular army trainees, which made the stay at Ingleburn rather interesting. On one occasion a platoon member released the prisoner when he was on guard duty because he felt sorry for him. On another occasion a Scotsman (Jock) had the duty of filling the water buckets one morning but forgot. When questioned by the OC as to why they were empty, he explained that the birds were real thirsty that morning. The battalion at this time had a terrific football team, in which I had the privilege to play.

About this time I also had the privilege of observing the RSM (WO1 Tom Muggleton) and decided that I would like to make the army a career and try to become a WO1. I can honestly say that Tom had a tremendous impact on my life and career, and for this I am truly thankful.

After about seven or eight months’ training we were all ushered into the lecture room one morning, warned for service overseas and given fourteen days’ pre-embarkation leave. This is what all the training we had done was all about.

Before leaving 4 RAR all reinforcements had a farewell dinner, which consisted of a slap-up feed and booze, and continued until we boarded the trucks to take us to the airport and off on the great adventure. The plane departed at 9.30 pm and went via Port Moresby, Guam and then to Japan, landing at Iwakuni. We crossed the Inland Sea by boat to Kure, and then went by truck to Hiro, where our training started again, this time to get us fit. The training consisted of marching up Hill 254 and running down, then long marches carrying all sorts of gear, 3-inch mortars, Vickers machine-guns, as well as all our gear, and culminated in attending the Battle School at Haramura. What an experience that was! The live firing exercises were great, and I have never been involved in anything so realistic, except for the real thing. It is a pity that the army could not continue with something like it now. On completion of this training we were all declared ready for Korea. I am afraid a few of us had to stay behind to finish the football season, which we ended with a victory.

The trip from Kure to Inchon in Korea in the MV Wo Sang was slow and uneventful. Then we went by truck to 1 RAR at the peace camp, where I arrived in April 1955. I suppose I can honestly say that until we sailed to return to Australia in 1956 it was fairly uneventful; a lot of hard work on the defence line called the Kansas Line, a lot of patrolling of the Demilitarised Zone, and a couple of R&Rs in Japan thrown in. A promotion course was squeezed in and I was promoted to temporary corporal.

When the battalion packed up and moved to Inchon to board the New Australia, it was rather a sad day as it took away an overseas posting where Australian soldiers could mix with troops of other nations and learn their trade. I believe this is now lacking in our forces. The trip to Sydney was uneventful and I do not think I will ever forget the morning we sailed into Sydney, one of the most delightful sights I have ever seen. The welcome we received when we marched through the city was tremendous, and of course it was extra great for me as I met my future wife.

Once the battalion re-formed, training started again, which was very interesting. There were trips to the field-firing area at Noosa, Queensland, and the senior soldiers were given specialist weapons courses, Vickers MG, 3-inch mortars, and signals. About this time I was posted to a national service unit in Sydney to become an instructor.

In about January 1957, I returned to 1 RAR at Enoggera camp to take over a section in D Company. The battalion was building up and training for service in Malaya and it was a rather hectic time. In the meantime the battalion played rugby union in the local civilian reserve grade competition and won it. The following year the battalion team formed the basis of an army team in the A Grade competition where they were very successful and produced some very good football players. The battalion took part in a number of large exercises during this period, both near Sydney, and in 1959 near Mackay in north Queensland. Around September 1959 the battalion boarded SS Flaminia and sailed to relieve 3 RAR in Malaya.

After our acclimatisation in Singapore and our compulsory stint at the Jungle Warfare School we moved up country and my company, now B Company, was sent to Sungei Siput where we began two years on operations in Malaya.

I believe that these were two of the most frustrating years I have ever put in. The constant patrolling, not seeing sight nor sound of any CTs, was soul destroying. I can now tell everyone who has heard the story of the patrol that walked backwards into Thailand in bare feet, that it was true; I know because I was part of that patrol. Take it from me, it happened.

Members of 1 RAR search a ‘CT’ in July 1959 in a ‘Malayan village’ constructed at Enoggera to prepare the battalion prior to its departure for Malaya (AWM photo no. CUN/796/NC).

During this time B Company was selected to take part in a SEATO exercise with the Royal Marine commandos in HMS Bulwark. This was a terrific opportunity for the troops to work with the commandos, and it was excellent value. So off we went to Singapore to train and prepare to board the aircraft carrier; even our sergeant cook went, as a private!

While in Singapore the NCOs were required to do a duty with the Royal Military Police (RMP) because the RMP had no jurisdiction over the Australian troops from up country. After our lectures on out-of-bounds areas and so forth, we went on leave, except for me who had the duty for that night, selected alphabetically of course. After patrolling around all the areas of Singapore and Johore Bahru, the patrol went into an out-of-bounds area in Singapore where two people in a trishaw were seen. The MP patrol stopped to question them and after a few minutes I was called to go forward. On arrival I found, sitting in the trishaw, my company commander and his second-in-command, quite obviously lost and being taken through the out-of-bounds area. There were very red faces but no charges were laid.

The company boarded the carrier and went off to sea to become ‘Australian Marine Commandos’. The trip was really an eye-opener, with the fleet being attacked by air and submarine, but one thing that really stuck in all our minds, I believe, was the many ways the British cooks could cook potatoes.

We landed on Borneo and began our advance inland with B Company taking over the point when the weather became bad and the other troops could not fly in their gear. The Australian troops had everything on their backs including five days’ rations, so off we went. By gee, there are some bloody big hills in that country. At the end of the stunt, after a bit of a dust up with the US Marines, the Australian troops were taken back on board and all went back to Singapore where we said our sad farewells to 42 Commando, Royal Marines and headed up country again.

The two years I spent in Malaya were of tremendous value to me. From landing on an LZ cut out of the jungle and going up and down river by long boat, to going on a two-man patrol for ten days with my heart in my mouth all the time and getting a bad report when I protested: it all made for a very interesting tour. Then there was the tiger that walked into the base camp ambush, resulting in a large number of huchies and dixies being shot up and the tiger returning about twenty minutes later to scout around again. That story made the Straits Times.

The families of the soldiers had a hard time as their husbands were out on patrol for about 30 days, back home for five and then off again. As I think about it, and remember my talks with the wives while I was at the Infantry Directorate many years later, I wonder if the modern day wife of the serviceman could put up with that type of life. But it made a very solid marriage in some cases and a very dedicated army.

At the end of 1961 my family and I moved to Butterworth, boarded a Super Constellation aircraft, and flew home to Australia, thus closing the chapter on the 1 RAR’s tour of Malaya and starting another chapter in the battalion’s history when we became a pentropic battalion. I was promoted to the rank of sergeant and transferred to the Mortar Platoon.

The period from 1962 to 1965 was taken up with trials, exercises and reequipping the battalion. We had a couple of very nice scenic walks over the Gosper Range on exercises such as Icebreaker and Nutcracker; we had a good trip from Jervis Bay to Eden on a landing craft, and a large number of helicopter trials lifting the battalion mortars, which consisted of twelve tubes in three sections, each of four mortars.

During this period we had a number of visiting units with us for exercises, and during one of these visits a tradition was born. After a visit from an Irish unit we had a farewell in the sergeants’ mess and the RSM of the unit presented our RSM, ‘Macka’ McKay, with a shillelagh, to be carried by all RSMs of 1 RAR on a battalion parade, close to or on St Patrick’s Day. I believe it is still in the 1 RAR sergeants’ mess.

Early in 1965 the battalion went through a tremendous upheaval. We went back to being a conventional battalion and we split to form 5 RAR at Holsworthy. This ended my career in 1 RAR and started my short stay in 5 RAR.

During our exercises in the Gospers we had many a humorous experience: I remember the Irish soldier with the Irish battalion who was found wandering around poking the ground and muttering that he believed he was on the moon instead of Australia and I can recall the time the troops of the Mortar Platoon told the Irish mortarmen, as they relieved them, that wombat holes were made by snakes that only came out at night and to set trip flares across the entrances to warn them when they were coming out. I believe that a large number of Irish soldiers never slept on that exercise.

Early in 1965 I went off on my warrant officer’s course, and 1 RAR was warned for service in South Vietnam. I came back to 5 RAR on completion of a guard in Martin Place to learn that I was to move to Scheyville as a warrant officer instructor. I did not get back to the regiment until 1969. In the meantime I served at the Officer Training Unit at Scheyville, with the AATTV, and with the 13th Cadet Battalion, before I found myself on the way to Woodside to help re-form 3 RAR for its second tour in South Vietnam.

On arrival at 3 RAR I helped form C Company then went back to New South Wales to pick up my family. On return I was appointed CSM of D Company, and with the OC started the Red Devils of 3 RAR. This period was, I think, one of the most rewarding of my career. One thing I must put straight for the record: the idea of the Red Devils of D Company was discussed by me and the OC, Keith Sticpewich, and my wife embroidered a badge for each of us. This was, I believe, the only company emblem ever to receive government approval. The Minister for the Army, Andrew Peacock, was to visit the company during training, and when he arrived by helicopter the GOC Central Command, Brigadier O.D. Jackson, was with him. The GOC questioned me about the object on my hat and I explained to him that it had been introduced to engender esprit de corps and to raise morale. Immediately Mr Peacock gave his approval for it to be worn. Thus the Delta Devils came into being and the badge was worn by all the soldiers with, I believe, pride.

I will not go into our tour of South Vietnam, as a lot has been written, except to say that after our first week there, we had a company of veterans, and after that tour I am proud to say that I served with a great bunch of soldiers.

The remainder of my service was spent away from the regiment, but while I was serving in the Directorate of Infantry, I looked forward to the trips back to the battalions of the RAR, even if it was only for a couple of days.

Often I am asked whether I miss the army, and what was the most memorable time of my career. The answer is ‘yes’ I do miss the comradeship and mateship of the army. My fondest memory is my service in the Royal Australian Regiment. Given my life to live again, I would do it all over and enjoy it just as much.

Major General David Butler, AO, DSO (from the 1990 edition)

The Korean War is all so long ago now that it is difficult to recall it, even more so to sort out the details sufficiently to compare one’s experience there with that of Vietnam. However, reading Robert O’Neill’s official history to refresh my flagging memory has proved a salutary experience. I became engrossed with his description of the difficult time we experienced in that long and bitter withdrawal in the first winter of the war. One sentence, dealing with events north of Pyongyang in early December, 1950 absolutely gripped me. ‘Shortly after midnight, communications were restored and Coad and Ferguson learned that the three companies of 3 RAR were the only force still east of the Taedong (River).’1

Thirty-eight years after the event, the effect of that sentence on me was electric. I was seized with a feeling of dread so intense as to make me shiver. Such a reaction after all those years, and in the quiet of my own home, disconcerted me. The reaction was foreign to my nature and I had not been quite so worried at the time. At first I was inclined to write it off as a function of my age, as a trick of the memory. Then I realised that I had been reading very carefully, attempting to put myself into the mind of the commanding officer. It must have heightened my awareness of another dimension of the peril the unit had faced at that time. Whatever the reason, I gained a deeper understanding of the burden carried by Bruce Ferguson in the opening campaign. To have been commanding the only Australian unit in the theatre and facing likely catastrophe must have been almost overwhelming for him. Lou Brumfield’s command of 1 RAR in 1965 could not have been any easier.

The severity of the Chinese counterattack devastated the US Eighth Army in late November 1950. Fortunately, 27th British Commonwealth Brigade had been in reserve when the Chinese struck and thereafter was committed to a series of rearguards conducted in the most trying circumstances. It was cruelly cold and many of the allied units around us were absolutely demoralised.

On a bitter, icy 2 December, after the frustration of a false start earlier in the day, 3 RAR deployed to defend a bridge over the Taedong River at a village called Yopa-ri. We were to hold it for the withdrawal of US 7th Cavalry Regiment, reportedly badly knocked about, and the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders from our brigade, who had gone to help them.

A US air strike on Yopa-ri was in progress as we moved into position, which was hardly a good omen. The company in which I was serving, C Company, remained with Battalion Headquarters west of the river and watched harassing fire fall on the three forward companies throughout the afternoon. Conditions steadily deteriorated, the river froze over and communications were lost with neighbouring units and formations. Towards the end of the afternoon, air reconnaissance checking on the targets of those earlier strikes reported that there were several thousand Chinese in the valley in front of us and several thousand in the valley to our flank. All of them were only a few thousand metres away from us. The report chastened us all. I remember our US forward air controller agitatedly claiming it was no place for a fighter pilot as he got into his jeep and departed down the hill in a hurry.

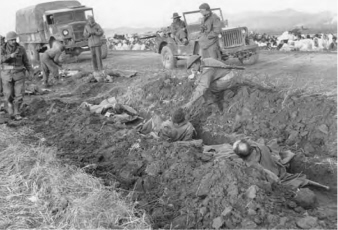

During the clearing of the roadblock about five kilometres south of Pakchon on 5 November 1950, wounded members of 3 RAR were brought back from the scene of action and placed in shallow trenches to protect them from North Korean mortar fire. The vehicles await clearance to move through while a large group of refugees sit in the background (AWM photo no. 146963).

In the evening the harassing fire continued and it started to snow quite heavily. About midnight communications were re-established with the news that the 7th Cavalry and the Argylls had gone back on another route. The battalion was dangerously exposed.

When woken to go back for orders I discovered I was covered in about a foot of snow and my boots were frozen solid. They would not yield to my clumsy attempts to knead them so, in absolute frustration, I forced my feet into them by jumping up and down on them. My sergeant, Don Parsons, watched and never fails to remind me of it whenever he sees me. There was little else that was funny on that night.

We withdrew at 5.30 am and not a moment too soon. The path of Chinese footprints in the snow around all our positions showed in the moonlight. Nobody spoke on the way out.

We reassembled some distance back and commenced preparations for the complete break in contact that was to take us south of Pyongyang. The orders puzzled and dispirited us because it was all so different to Commonwealth doctrine. Most of the soldiers looked on the big break of contact as running away and did not like it at all. We had so far bested any enemy that had been put against us.

It was during those preparations that the commanding officer, for the first and only time I can recall, came round and spoke to each of the assembled companies. We were obviously in deep trouble. He put it all quietly to us, reminded us of the reputation Australian battalions enjoyed in previous wars and enjoined us to be sensible, despite all the ominous rumours around us. He told us there was a physical limit to the number of enemy that could be put against us, the whole of the Chinese army could not attack 3 RAR at once and that was all we had to think about.

We then embarked on what turned out to be a twelve-hour trip in the most awful conditions. We were not told where precisely we were going, simply that our advance parties would meet us down the road. C Company travelled on the top of American tracked artillery tractors and I could not imagine a colder or more uncomfortable ride. The column crawled along a road choked with refugees and demoralised ROK soldiers in such abject conditions as to defy description. There were babies lying frozen among the bodies alongside the road. As the war diary reported we found the move ‘most miserable and cruel . . . due to the intense cold and [it] will most likely be recalled as the Battalion’s bleakest day in Korea’.2 It was nearly midnight when our adjutant, Bill Keys, appeared on the road calling for all Australians to get off the vehicles. We had arrived at Hayu-ri. It was hardly a staff college performance, but the battalion was intact, not a soldier was missing and it was the end of a pretty awful day.

To my mind what was most remarkable about all this was that the battalion that endured this trial had only assembled two months before. On 25 July 1950, when it was announced Australian troops would serve in Korea, 3 RAR’s strength was twenty officers and 530 other ranks. It would have to be brought to 39 officers and 971 other ranks for operations.3 The first reinforcements, a draft from 2 RAR, arrived on 30 August 1950, the vanguard of 21 officers and 440 other ranks who were to march in by 18 September. Four rifle company commanders, the Support Company commander and the RSM came in those drafts. The commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Green, arrived on 10 September, we sailed on 28 September and he died of wounds on 1 November.4

There had been time for two short battalion exercises before departure. The first, 13–16 September, was severely interrupted by torrential rain and flash floods. It was the first time a Support Company had been deployed in the army and was hardly auspicious. The Support Company elements detached to the rifle companies and the Battalion Headquarters (including the commanding officer) were not fed for the whole exercise. God knows what the commanding officer thought about his new command! It came as no surprise that Support Company had a new CQMS by the time they got back to barracks. The second exercise, 21–22 September, was devoted to company demonstrations and practice of the phases of war and Support Company weapon demonstrations.

The exercises were of the most elementary nature, just simple deployments. The brand new communications network could not have handled much more. Within the battalion only C Company remained intact. The other companies had come together, with men from the three battalions of the regiment and the specially enlisted K Force, in the last few days. We were still drawing stores and getting to know one another. By any standards, by AIF experience or Vietnam, 3 RAR should hardly have had a chance. Perhaps we were too busy to reflect on our circumstances, but there was no lack of confidence in the unit. I suspect that those of us who had not been to war rather took it that things always happened that way.

Mark you, I was later with 2 RAR at Puckapunyal when that battalion went to Korea and, even by 1952, the system was not a whole lot better. Whereas the companies had done a lot of training, there was only one battalion exercise, which was not much more advanced than the 3 RAR exercises in September 1950. By then, I was signal officer and I recall I could not get any signal cable, there was none in Australia. Eventually I tracked down, and was given, by the School of Signals, then at Balcombe, three miles of D3 twisted cable, which had been declared beyond local repair. We had to pick the cable up ourselves and then spent nearly a week repairing it sufficiently for it to be gingerly nursed through that exercise. The local brigadier’s boast that we were the finest trained battalion ever to leave Australia was widely reported.

Nonetheless it remains that 3 RAR in that first year of the war achieved the impossible. In hindsight I still cannot believe that the army had been allowed to decline to such a state by 1950. By comparison, the arrangements for the manning, training and despatch of 6 RAR to Vietnam in 1969 were superb, not only in their technical quality, but also in the spirit in which they were provided.

Just as 3 RAR in 1950 was a practical balance of Second World War experience and young regulars, 6 RAR in 1969 was a match of competent regulars, many with a tour in Malaysia and Vietnam under their belts, and well-trained national servicemen. The unit came to strength in a nicely regulated pattern, bearing in mind the balance of national service intakes three months apart was discontinuous. We had to plan for their departure/replacement at three-monthly intervals in the theatre. By 1969 the army was experienced in this pattern and we were allowed to corps-train two intakes of our own national servicemen. It was in everybody’s best interest for them to have as long an uninterrupted stay in the unit as possible.

The training cycle was excellent and quite testing, but it had to be adjusted for us. We were the first battalion to train and embark from the isolation of Townsville. The local headquarters was small and inexperienced so we had largely to write our own program and arrange our own embarkation. It was some comfort that the battalions that followed adopted the cycle we developed.

I would not want to make light of our time in Townsville. We had to overcome considerable difficulty in almost every area of battalion life, but that is a separate story. Sufficient to state the battalion succeeded and was absolutely self-reliant as a result of it. However, I would be remiss if I failed to make special mention of the sergeants’ mess and their contribution to all that we achieved. Largely intact from the first tour in Vietnam, ably lead by a superb RSM, Jim Cruickshank, they

The commanding officer of the newly arrived 6 RAR, Lieutenant Colonel David Butler, is welcomed by the commanding officer of the outgoing 4 RAR, Lieutenant Colonel Lee Greville, on HMAS Sydney, at Vung Tau in May 1969 (AWM photo no. BEL/69/331/ VN).

were a tower of strength in Townsville and absolutely without peer in operations in Vietnam.

After all that build-up I have finally come to the real point I wish to make in my story. Operation Lavarack, 6 RAR’s first operation in 1969, because of the unexpectedly heavy demands it imposed on the soldiers and on the whole framework of the battalion, was reminiscent to me of 3 RAR’s first experience in 1950.

In the manner of first operations it was intended to be a comfortable shakedown. Deployed into an area north of the task force base which had been quiet for some time, the battalion ran slap-bang into both the 33rd and the 274th NVA Regiments. The contacts were immediate and heavy. The largest enemy main force incursion into Phuoc Tuy province since Long Tan in 1966 was to prove a stern test for the new battalion. In a series of sustained actions though May and June 1969, involving over 100 separate contacts, 6 RAR/NZ (ANZAC) drove the enemy from the province.

The operation was unusual not only because of its intensity and the numbers of enemy involved but also because of the way it unfolded. Long Tan had convinced enemy commanders to never allow the Australians to fix them in place in daylight. Thereafter they operated in small groups to dissipate task force effort and evolved complex bunker systems that enhanced their protection against our formidable artillery and gave them enough depth to delay rapid deployment against them. It was rare therefore to find the enemy moving in strength and fortunate for us to be deployed astride their routes.

Within one week the five rifle companies had become heavily engaged. What we did not realise at the time was that one enemy objective was to attack the village of Binh Ba and that we were deployed on their approaches. Needless to say our actions severely interrupted the enemy deployment and forming up, and resulted in their attack being badly coordinated and late, so much so that the battalion of the 33rd Regiment was still in the village next day.5 Since all five companies of 6 RAR/NZ were in contact or facing imminent contact, D Company, 5 RAR was deployed, initially under command of 6 RAR, to carry out the brilliant attack with armour that is such a proud part of our regimental history.

Several days later the other battalion of the 33rd Regiment, after a heavy bunker action with B Company, 6 RAR/NZ, strongly supported by the 101st Field Battery, broke and fled north in daylight right across the front of a very aggressive V Company, 6 RAR/NZ and was again hammered. The enemies’ agony did not end there as captured documents revealed their commanding officer was severely censured for so dangerously exposing his battalion through this incompetence and lack of battlefield discipline.

There were so many actions of a similar nature during Lavarack it would be impossible to single out any as highlights without wronging those not mentioned. At the time, we recalled with wry amusement Brigadier Bill Weir telling us after our final exercise in Shoalwater Bay that no operation in Vietnam would match the tempo of that artificially contrived for the exercise. Lavarack began at a fierce pace and did not slacken until the enemy were driven out a month later.

There is no way the good brigadier could have foreseen that Rodney Chandler and his platoon would carry out the largest Australian ambush of the war against over 100 of the enemy. I have a clear recollection of a company commander reporting one night that his headquarters (then five strong, we operated extended area ambushes) was in the path of 100 approaching enemy. His terse transmission ended ‘Engaging, out’. Nor was wide prominence given in the battalion to his second-in-command, one of the five, who went well forward that night on his own on several occasions to replace expended claymore mines. The whole battalion gave and expected that sort of commitment.

The victory of Operation Lavarack was achieved, just as the challenge was met by 3 RAR in North Korea in 1950, by the unrelenting determination of every soldier to keep going. The demands made on each individual tested them to their limit and beyond. The companies were widely dispersed so there was a heavy daylight patrolling burden and every night was spent in ambush. The chance of contact was ever present so there was no respite for that long month. Lavarack was a memorable victory and a unique offensive success for the regiment previously so noted for its stubborn defences against overwhelming strength in places like Kapyong, Long Tan and Coral.

Private Montey Paul, attached to a 400-strong battalion of the 18th ARVN Division, moves cautiously down a jungle stream on Operation Quyet Thang in November 1969. The exercise was the culmination of six weeks’ intensive training by the ARVN battalion (AWM photo no. BEL/69/805/VN).

How different those Vietnam battles were to the essentially main force battles fought in Korea: classic attack, defence and withdrawal in the move to the Yalu and back; the orthodox divisional attack in Operation Commando in 1951 to secure the line held for the rest of the war. From then on it was static defence: intensive patrolling, occasional raids and sometimes limited attacks and counterattacks. All was supported by plenty of artillery.

Not unnaturally the regiment’s skills developed with the experience. The detailed planning and disciplines demanded by two years of intensive night patrolling in 1952–53 were extended by the precise and careful demands of the Malayan Emergency from 1955 on. The great virtue of patience was added to the regiment’s repertoire. The regiment was ready for Vietnam. The result of many years of almost unbroken contact with the Queen’s enemies was evident for all to see. It remains to this day.

I leave you with a thought that has intrigued me over the years. By my count, the regiment in that long stint of active service, 1950–72, filled 27 battalions. Although four members of the regiment had won Victoria Crosses while serving with the AATTV, no VC had been won by any of the battalions. The record shows battalions have endured more than their share of adversity in that time and, on many occasions, have faced overwhelming odds. Whereas it may well be some sort of commentary on the honours and awards system, it also has to be a measure of the quality of all those fine young men who have served in the regiment. On all those occasions of dire emergency, there has never been a shortage of men who would and could move on the battlefield or of leaders who were unhesitating and adept tacticians in battle. ‘Duty First’ is truly the measure of the regiment.

Lieutenant Colonel Barry Caligari and Brigadier John Caligari, DSC (for the 2008 edition)

Dad (Barry) and I (John) are able to offer an interesting and perhaps unique perspective of the Royal Australian Regiment in peacetime and on operations. In total we’ve served the Royal Australian Regiment for over 50 years and at family gatherings often discuss the constants and contrasts over that time. When Dad and I get together we laugh and shake our heads in disbelief or amazement at what has and has not changed in the regiment.

Dad enlisted as a soldier in June 1956 and ended his career in the army as commanding officer of the 1st Battalion in 1983. I graduated from the Royal Military College in December 1982 and marched into 1 RAR as OC 2 Platoon, A Company, 1 RAR, under Dad’s command—a regimental first. Our experiences in 1 RAR are the link between our two careers. We have both served over 27 years in the Australian Army, with over twenty years between us in battalions of the regiment.

Similarities and Differences

In many respects our careers have been similar but at the same time many of our experiences have been vastly different. We were both assault pioneers, did staff college overseas, served in the Office of the Chief of Army (or was that Chief of the General Staff!) as military assistants and both commanded the 1st Battalion— in fact we are led to believe we are the only father and son combination ever to command the same battalion of the regiment! However, the opportunities afforded the younger by the sacrifices and experiences of the older characterise the differences in our careers. Dad began life as a private soldier after spending some time in the civilian workforce, without even a school leaving certificate. He was commissioned after nine years and a six-week ‘knife and fork’ course, having made it to sergeant, and having served on two tours of active service. I had it ‘easy’ (my words)! I entered the regiment via the Royal Military College on a scholarship after completing my higher school certificate, graduated with a degree and was posted as a rifle platoon commander.

In that time, many things in the regiment have stayed the same and many have changed. Dad and I agree that mateship and camaraderie, that laconic Australian

Lieutenant Colonel John Caligari, commanding 1 RAR in East Timor from October 2000 to April 2001 (right), in discussion with Lieutenant Colonel Agung Rhisdhianto (left), commanding the TNI’s 131st Territorial Infantry Battalion, on 1 April 2001 at Batuguarde. The maintenance of good cross-border relations with their Indonesian counterparts was an important part of maintaining security on the border for the battalions serving there (photo: John Caligari).

humour, and a predisposition for getting the job done despite the distractions and the odds, are as evident today as they were in 1956, and no doubt on Anzac Cove for that matter. However, there are clear differences, especially in appearance. When Dad joined the army, soldiers of the regiment were dressed in starched and ironed khaki drills, spit polished leather and brass, equipped in 38 pattern webbing and armed with .303 rifles, Bren guns, Vickers heavy machine-guns and 2-inch and 3-inch mortars. When I commanded 1 RAR on operations in East Timor in 2000, soldiers were dressed in disruptive pattern camouflage uniforms, equipped in ergonomic fitting chest webbing and armed with 5.56 mm Steyr rifles, 5.56 mm light-support weapons, 7.62 mm MAG 58 machine-guns and 81 mm mortars.

Other differences revolve around our early experiences as officers. Leaving 3 RAR in Borneo as a sergeant, and accompanied by Don Parsons and Kevin Grayson, Dad returned to Australia to attend the Officer Qualifying Course at the Jungle Training Centre in Canungra in 1965. On graduation all three returned to Borneo as the oldest but most junior lieutenants in the regiment. Then after a briefing tour of Vietnam (visiting 1 RAR in fact) they went back to Terendak Camp in Malaysia to discover that commissioned rank was not all that it was cracked up to be. They soon found themselves having to conduct audits of the sergeants’ mess; and collect, count and break down 500,000 Malaysian dollars into pay packets for the battalion’s homecoming. In contrast, my arrival in the regiment from RMC was characterised by apprehension and excitement over how a 22-year-old would command three experienced section commanders and an ‘old’ sergeant.

Dad and I still spend hours trying to convince each other why things are better now, or why they were better then. In the end we agree its ‘different’ now, soldiers need to cope with different things, and some things had to change. In 1956 as a soldier, Dad didn’t own a car and the company car park was lucky to have three cars in it; now it’s full. In the lines at 3 RAR Dad lived in a room with three other soldiers. Now most soldiers have a room to themselves. We used to have ‘real’ battalion duties in the old days! Contractors do most of them now. Married quarters for soldiers were of very poor standard years ago, compared with today’s. In fact Dad didn’t even qualify for MQ until he had been married for seven years, been on two years of active service and had three kids! In 1981 Mum gave evidence on behalf of army wives to a Senate Committee on the poor standard of housing for soldiers. By 2000 the married quarters Mum and Dad called home when Dad was CO 1 RAR was a corporal’s married quarters. Housing had become so good and egalitarian that when I left Townsville, my own home in Annandale was rented by a private soldier. And of course the education standard is very much higher today. In the early 1960s George Mansford and Dad completed the Victorian leaving certificate together so that they would be eligible for a job with the public service, should the need arise. Today most soldiers have the HSC and many have degrees.

Our Common Approach

But the thing that both of us return to each time we get together, and the reason we both enjoy the army so much, is the people. In particular, the characters we’ve worked with. We agree that all Australian soldiers have different capacities but most importantly they all have their ‘heart in the right spot’. To understand this is to understand what courage, initiative and teamwork really mean.

We’ve both seen extensive service with other armies around the world on operations and in schools and from this two things stand out. First, the training we have received is world class and sets us apart from those armies more institutionally indoctrinated. And second, that the egalitarian ‘arrogance’ of the Australians of the First World War runs deep in all of us in the army and it stands us in good stead wherever we serve. And so for Dad and me, it is a deep respect for the qualities of the Australian soldier and the privilege we have both enjoyed in serving with and commanding them that dominates our discussions. Of course Dad spent nearly the first decade of his career as a soldier, but the strong appreciation and high regard for the Australian soldier, warts and all, is a strong sentiment we share.

Our affection for the Australian soldier is exemplified in our respect for the most senior of them and as a young man, I listened intently as Dad spoke with pride and satisfaction to Mum and his friends about his experiences in the regiment. As a soldier Dad would talk of the likes of RSM Joseph Bede O’Sullivan, MBE, a man who ‘never slept’ and always seemed to be on the spot when soldiers were not doing the right thing. On one occasion this particular RSM caught Dad, as a private soldier, with a meat pie in his hand as the national flag was being lowered and ordered him, from over 100 metres away, to ‘get rid of it’. So Dad stuck the pie and sauce into his pocket! Dad had stories of these RSMs from his early days as an officer too. He talked about RSM A.P. Thompson, MBE, who was given a serious troublemaker to manage, whose record read ‘like the memoirs of Darcy Dugan’. As adjutant, Dad couldn’t get any of the company commanders to take this problem soldier, so he gave him to the RSM, so that the RPs could ‘keep a close eye on him’! To Dad’s amazement, within a few months the RSM suggested he’d be prepared to ‘give the lad a stripe’. That soldier went on to become a very competent section commander in Vietnam! The message to me was that there was great satisfaction in working with a team where everyone is encouraged to achieve their best. The unambiguous impression I got from these and many other stories like it was that soldiers are the regiment and RSMs are their epitome. So much so that at RMC, the two biggest influences on my decision to go to Infantry were RMC RSM, ‘Lofty Eiby’, and my company drill sergeant, Brian Boughton. I later served with RSM-A Brian Boughton in the Office of the Chief of Army when I was the MA and it was like old home week for the year! As CO 1 RAR, I also had two of the finest RSMs a battalion commander could ever have wished for, especially on operations, with RSMs Steve Ward and Al Gillman. And although none of my doing, I am proud of the record of 1 RAR of the early 1980s which in 2000 turned out RSMs in 1, 2 and 6 RAR. To me this was strong evidence of a professional culture in 1RAR, as Dad’s legacy, and an inspiration and example for me as I arrived in the regiment.

The other thing about the regiment that we are both grateful for is the acceptance of mistakes or errors of judgement, providing of course they were made for the right reason. We’ve had each other rolling in laughter with our tales of ‘stuff-ups’. The one I remember best about Dad was as adjutant of 7 RAR, when COMAFV, Major General A.L. MacDonald (Dad always referred to him as A.L.), was visiting the CO, Lieutenant Colonel E.H. Smith, and A.L. casually asked E.H. how many of the battalion’s soldiers wore glasses. E.H. rang Dad to find out and he, thinking a quick answer was more appropriate than an accurate one, gave a rapid response based entirely on a ‘stab’ of how many wore glasses in BHQ multiplied by 20. A.L. was astounded at the prompt reply and E.H. insisted COMAFV inspect the filing system that could produce such a quick answer. The noise in the orderly room attracted Dad’s attention, and he was obliged to admit that he ‘had taken a punt’. A.L. left disgusted and E.H. felt foolish for ‘gilding the lily’. For my own experience, I committed the usual list of ‘errors of judgement’ as a young platoon commander, for which I was duly punished, including a stint of fourteen days straight as duty officer at the direction of the CO, Lieutenant Colonel Peter Cosgrove. In fact, it was while doing this stint that I met my wife at the Mater Hospital in Townsville while visiting a soldier there, so I am eternally grateful! Funnily enough we both ended up years later as military assistants (MA) to these particular men. Dad became A.L.’s MA when he was Vice Chief of the General Staff and I was Lieutenant General Cosgrove’s MA when he was Chief of Army. They must have forgiven or forgotten; either way we are grateful.

Active Service

Our combined experience of the regiment on active service since 1956 gives us plenty to discuss and plenty to learn, each from the other’s experiences. Our mutual respect for each other’s experiences on operations means there is little argument, but much discussion on tactics, techniques and procedures, a little on strategy and it always ends in admiration for result.

When in 1993 I found myself on operations in Somalia as the OPSO of 1 RAR, I quickly recognised the similarities to Dad’s descriptions of what 3 RAR got up to in Malaya in the 1950s. It didn’t take long for me and others to recognise the significance of the Templer Model for counterinsurgency operations; or to use Templer’s phrase, which has become doctrine today, ‘winning the hearts and minds’ of the people. Dad’s two years in Vietnam, with 7 RAR and AATTV, were also noteworthy as I deployed with 1 RAR to Somalia on the first battalion-sized operation since Vietnam. Of particular concern to the CO, Lieutenant Colonel David Hurley, and all of us in the 1 RAR Group in Somalia, was the high incidence of unauthorised discharges. Despite the battalion having been issued the Steyr not long before, the problem often exercised our minds more than did the enemy. But remembering Dad’s sage advice based on his Vietnam experience helped me put our problem in context. He had also given me good advice on the necessity for the passage of timely and accurate information. As he’d forewarned, the first reports in contact were highly inaccurate and confused. It was up to us in the battalion command post to distill the most important bits to make critical decisions—did we need to despatch APCs or an ambulance? Higher HQ got what they needed and we largely avoided the necessity to correct inaccurate information with them. The clarity of the battalion war diary has, as far as I am aware, not been questioned to this day. In the end, it’s a careful balance between ensuring the soldiers’ interests are protected and accurate information is received by higher HQ in a timely manner, as every incident becomes the subject of investigation and confirmation of the application of the rules of engagement. Dad recognises a big difference from his operations in Malaya and Borneo!

By far the high point of my career was command of the 1 RAR Battalion Group of 1100 soldiers on operations in East Timor. Like Somalia, Dad’s experience was very valuable to me through the tradition of stories told and advice. This time it was Dad’s experience in Confrontation in Borneo in the early 1960s, and his understanding of Indonesians (including speaking bahasa Indonesia and studying Asian Studies at ANU) that was of specific help. In particular, I felt well equipped to work with Lieutenant Colonel Agung Rhisdhianto, CO of the 131st Battalion, positioned across the border in West Timor, Indonesia. He and I became good friends and were on all occasions able to resolve issues directly without the UN observers, often to their disappointment. I was also very much aware that the enemy likely to cause us the most casualties was malaria and dengue fever. As a child I saw Dad suffer from bouts of malaria. I understood that, in those days, there was nothing that could cure him and that anti-malarials would not prevent dengue. In East Timor I waged war on these two afflictions. In short, I recognised that maximum effort on prevention was the best course of action. I increased the number of ‘blowflies’ (hygiene duty men); set strict requirements for wearing long sleeves and other personal precautions; and had accommodation, work areas and even nearby villages ‘fogged’ on a relentless schedule. The battalion group had no cases of malaria contracted in the AO and it demonstrated outstanding control and superb discipline by my officers and soldiers.

Command of 1 RAR

The most important of our common experiences in the regiment relate to the 1st Battalion. We both thought all our Christmases had come at once when in December 1982 we were serving together in the 1st Battalion. Although it was for only a short time, both of us understood the significance of this event in Australian military history. Little did we know that the biggest ‘Christmas’ of all would come seventeen years later when Dad handed over the CO’s Sword, a sword that belonged to Lieutenant Colonel Dobbin, CO 1st Battalion, First AIF, from the outgoing CO, Mark Bornholt, to me in front of the men of the ‘Big Blue One’ on the 1 RAR Parade Ground in Townsville.

The battalion was very different for each of us, but in so many respects it was the same. When Dad assumed command of the 1st Battalion at the end of 1980, the battalion was undermanned and the raising of the operational deployment force of the 3rd Brigade had just begun. Townsville was not a sought-after posting destination. By the end of 1999, 1 RAR was at full strength, the operational deployment force was demonstrating its capability on operations in East Timor, and Townsville was a highly sought posting. But the battalion area looked almost identical, except for the trees Dad planted which made the area decidedly more attractive than the battalion lines across the road. And I sat in the same office, with the photos of all the previous COs looking over my shoulder—although I had a computer! Everything looked and felt very familiar and very comfortable.

There are a few hallmarks of our approach to other aspects of soldiering. We are both strong proponents of the slouch hat, neither of us having worn anything else in our careers; and opponents of the stable belt and beret, particularly under the sun of north Queensland. In our time in 1 RAR we were very proud to wear the green puggaree. We’ve spent more time looking after that troublesome Septimus than we care to remember! Mum and Dad often took on the task of caring for him when the battalion was away, including when we were in Somalia. Both of us have a particularly soft spot for the 1 RAR band. Dad was involved in the early days with the amalgamation of the North Queensland Area Band and the 1 RAR band; and I was the first CO to take the band on operations since then. Throughout our history in 1 RAR, the 1 RAR band has been an important part of battalion life and the battalion’s presence in north Queensland. We both believe ‘Waltzing Matilda’ should never be tortured by pipes and drums (although we haven’t been allowed to ‘trumpet’ that too loud as Mum is Scottish born!).

The event that drew together all of these threads of our experiences in the regiment was the return of the battalion to Townsville from East Timor in 2001. The battalion arrived home for the mandatory welcome home parade through the streets of Townsville and a medal parade on Coral Day on the battalion parade ground. I invited the veterans of 1 RAR to march on parade to present the active service medal and infantry combat badges to individuals and sections. Where a special association or relationship existed, a special presentation was made. Dad presented my AASM clasp to me. This was a very special occasion for both of us. It represented in one ceremony, the similarities and dissimilarities in our lives and our careers, on familiar ground.

Conclusion

We are both proud to have had the opportunity, honour and privilege to contribute in our own ways to the highly professional and world-renowned Australian Army, the fighting heart of which is the Royal Australian Regiment—a worthy guardian of the Anzac tradition. Our family tradition of sacrifice for Australia is significant with family connections to every war in which Australia has participated since Federation. Between the two of us we account for all but the first ten years of the history of the Royal Australian Regiment. And the tradition looks set to continue. My nephew is at ADFA now and will soon move across the hill to RMC, and he is intent on joining the regiment. And my two sons look set to follow in their old man’s, and his old man’s, footsteps into the regiment, having commenced at ADFA, after having been sworn into the army by me as Commander 3rd Brigade, at Jezzine Barracks in Townsville in January 2007.

Major James Cruickshank, MBE (from the 1990 edition)

I commenced my service in the RAR with somewhat mixed feelings. I had served in the Royal Marines for more than four years and transferred to the Australian Army because my family had immigrated to Sydney. However, the vastness of my new country, relaxed lifestyle and innate friendliness of the people made me an instant convert to the Australian way of life. Posting to 1 RAR, at Ingleburn, New South Wales, was a slightly different kettle of fish and required some adjustment to my thinking. This was November 1950.

Training in Australia, 1950–52

At the time 1 RAR was grossly under strength. Commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Kelly, it was engaged in training K Force reinforcements for 3 RAR then serving in Korea. It was also, with the Puckapunyal-based 2 RAR, a source of reinforcements from within its own establishment. Remember that the battalion was really in its infancy and had only been back from BCOF, Japan some two years. The barracks were of Second World War vintage but had been remodelled to give four-soldier room accommodation. The shower, ablution and latrine blocks were comparatively primitive, partially open to the elements and with coke-fired boilers. The kitchens and mess halls were even more primitive. Meals were served in the open and consumed in unlined huts. I remember that mutton and pumpkin figured largely on the menu and that occasionally the meat was flyblown. One could always guess the day of the week by the menu; for instance, it was always roast pork on Sunday. Cooking and washing up depended on fire power, the washing up being done in 44 gallon drums cut in half lengthwise—in the open, of course. Kitchen duty was way down on the scale often. Splitting firewood and washing up in greasy water was soul destroying. Wiles cookers, Sawyer stoves etc. were then presumed to be state-of-the-art cooking equipment.

Of course, I was not the only soldier of UK origin in the army. The 1950s saw a large recruiting program in the UK to build up the embryo Australian Regular Army and, I suspect, to provide another source of manpower for service in Korea. It was a scheme that produced mixed results. It is certain that regimental checks with the War Office in the UK were not carried out as meticulously as perhaps they should have been done, because some low-quality soldiers made it to Australia. On the other hand, there was a great deal of experience there too and it is probable that the army gained a great deal more than it lost through discipline problems (AWOL etc.). In the 1960s and 1970s a number of RSMs and other WOs in RAR battalions were of UK origin.

Those early days of my service were with A Company, 1 RAR. It was commanded by Captain C.D. Kayler-Thomson, the CSM was Australian–Chinese WO2 Stanley Wing-Quay, the company second-in-command was Captain J. Waterton, ex-Royal Marines and later to win the MC with 3 RAR, Lieutenant ‘Jock’ McCormack was my platoon commander and my platoon sergeant was Bill Chick.

Uniforms were a source of some initial amusement. The army was changing over from the old service dress, circa 1914, to battledress. The emphasis was about to change to black so we all had to ‘raven oil’ our tan boots to produce the Boot, army black. These were worn with anklets, web. The khaki drill (KD) uniforms were in all sorts of patterns and if there was the need for jungle greens this was achieved by dyeing the KD. Often this resulted in a sort of murky blue shade.

We trained hard with Rifle SMLE .303, 9 mm Owen submachine gun, the EY rifle (rifle grenade), the PIAT (Projector, Infantry Anti-Tank), the 2-inch mortar and 36M grenade. There was great emphasis on route marching and bayonet training. I will never forget my amusement the first time I heard the contradictory order ‘For bayonet training—get dressed’. Formed up in three ranks at open order, this meant stripping to the waist and divesting oneself of equipment. Another unusual term then used was ‘Serafile’ instead of ‘Supernumerary rank’, serafile of course being a cavalry term, an obvious throwback to the Light Horse. Parade grounds were unsealed and training was largely done within the camp confines.

Social life in the camp was somewhat limited. There was a canteen conducted by the Army Canteens Service. Cigarettes and tobacco were rationed but we each had a ration card. Draught beer was available in the ‘bar’. This had a dirt floor and you took your own enamel mug. Occasionally dances were conducted at the Church of England Hut. At the Everyman’s Hut, Eddy Bentley supplied tea and violin support for hymns etc. Other than that one went farther afield to Liverpool or Sydney. On Sunday a cold beer could be obtained at the Good Intent at Campbelltown (mine host, Titus Oates, the Second World War air ace), as a bona fide traveller. Those were the days of the beer swill when the pubs closed at 6.00 pm or earlier if the beer ran out. There were always advantages to being a soldier in 1950. We enjoyed postal, telephone, telegram and public travel concessions. These have all been removed over the years, I suspect after pressure from envious public servants.

Life to some extent was varied. There was the occasional guard duty in Sydney at Victoria Barracks. This would be for a fortnight at a time. Off duty, the soldiers would make use of the adjacent hotel, then named the Greenwood Tree. Military tattoos were an annual event and we would perform at the Royal Easter Show, sometimes doing calisthenics or set-piece mock attacks etc. For guard duty, we were issued with a prewar vintage cape, against inclement weather. These were quite voluminous with an internal cross-strap arrangement and could be worn with the cape thrown back when not raining. This latter appearance gave rise to the nickname, ‘Mandrake’ cape, after the cartoon character. Disciplinary problems in those days were probably little different in essence to today, with two major exceptions. There were no drug problems (if one excludes alcohol) and very little stealing, or certainly never from one’s friends. It was safe to leave money, cigarettes and such in open view, with confidence. This also applied to the sanctity of one’s food and water supply on exercise. There was a strict ration of one water bottle per man per day and perceived stealing attracted fairly harsh physical retribution.

The early 1950s saw the army still on war service as no peace treaty had been signed with Japan. Charges levelled were under the Army Act (Whilst on War Service) and escorts were armed. There was less inclination to charge soldiers for minor offences. ‘Round the back’ was often the peremptory command from seasoned Second World War NCOs, for a little diligent laying on of the hands!

Married quarters, certainly at Ingleburn, were rudimentary. These were just converted army huts. They were without the ‘sophistication’ of the Swedish prefabricated buildings common from 1952 to 1987.

The vast grass areas around Ingleburn Military Camp were kept trim using horse-drawn grass-cutting machinery. These army horses (Clydesdales) were stabled at the nearby DID (Demand and Issue Depot) AASC. I remember once the operator left a team untethered but with the machine in gear. The team ran away, blades clicking furiously, soldiers scattering, and eventually came to a halt when the team straddled a tree. In the sudden stop the machine swung around and severely cut one horse. The animal was despatched by our regimental police sergeant, ‘Sandy’ Gray, using the unit pay representative’s .38 pistol.

In 1951 there was the threat of further trouble in the Hunter Valley coalfields (troops had been used to break a national strike in 1949) and we were readied for possible deployment. Truck drivers, carpenters, train drivers etc. in our midst were identified and the unskilled were identified for other duties. I was in a group sent to Army Training School (ATS) Ingleburn. There, over two weeks, we were trained as blacksmith’s strikers. My AAB–83 (Record of Service) always thereafter carried the entry ‘Qualified Blacksmith’. In the event, we were never used as the strikers went back to work.

Things looked up after we were warned for duty in Korea. This was in 1951. At the time our CO was Lieutenant Colonel I.B. Ferguson, DSO, who had commanded 3 RAR at Kapyong. He had changed places with Lieutenant Colonel Frank Hassett, previously our commander. We then had another change in command with Ferguson and Lieutenant Colonel Ian Hutchison, DSO, MC, changing places (1 RAR/ 13 NS Training Battalion). Hutchison had commanded 2/3rd Battalion during the Second World War and it was not long before he had attracted a number of his ex-colleagues into the battalion—officers and NCOs. The adjutant (Captain Eric Smith) and RSM (WO1 S.H. Smith) were two of those.

At this point I was moved to Support Company as a section commander in the MG Platoon with eventual promotion to sergeant. This platoon was commanded by Captain C.H.A. East, who had as his second-in-command Lieutenant Doug Yeats and Sergeant ‘Rusty’ Churches as platoon sergeant. East had served in 2/9th Battalion, Yeats with the British Army and Churches with 2/13th Battalion. They were the experienced machine-gunners. Most of us joining the platoon were ‘clean skins’ but we worked hard and became proficient. Our pre-embarkation ‘Shoalwater Bay’ type exercise was done at Green Hills—Darkes Forest.

Soon we were in the pre-embarkation phase. This included preparation for quitting the lines in which we lived. We rehearsed packing our gear for consignment by sea, packing our load-carrying equipment and stripping the barrack rooms. At least twice we placed all furniture, wardrobes etc in piles on the parade ground and then returned them. In one company Q store a number of surplus .303 rifles were found in the ceiling. Exquisite ‘Q’ accountancy!

The big day eventually arrived and off we went by bus to Sydney, on the way booing one sergeant who had elected to stay at home. We had taken umbrage because for some time he had trained his soldiers very hard, all the time telling them that he wanted ‘36 killers’ to go overseas with him. I remember us having a cut lunch at the old Crystal Palace site and then led by our band with teetotaller drum major Sergeant K.K. ‘Plonky’ Hunter in command, swinging through the city. The salute was taken on the Town Hall steps. At Circular Quay we had a little time with our families and friends before boarding HMT Devonshire and preparing for sea.

Leaving the quay we were confronted by the spectacle of left-wing waterfront unions exercising their democratic right by proclaiming us, on banners etc. as murderers, or something of that nature. Many of us wished we could have exercised our democratic rights in response, as we were shortly to do in Korea.

With the 1 RAR Machine-Gun Platoon in Korea

Transportation to Japan was per HMT Devonshire to Kure where we disembarked in November 1952. We were accommodated at Kaitaichi, midway between Kure and Hiroshima, in tents erected on the concrete foundation of old BCOF accommodation. Equipping and training took place over a couple of weeks. Each company had an indoctrination at the British Commonwealth Division Battle School, Haramura, commanded by an eccentric British lieutenant colonel by the name of Lonsdale.

Movement to Korea was by the Empire Longford to Pusan, then train to Tokchon, the divisional railhead. From there we were transported to the Kansas Line. The feature of our training I remember best was the week I spent with B Company, 3 RAR learning the routine. The platoon was commanded by a fiery Pole, Lieutenant George Zwolanski, and had a MG section located with the platoon. Here I went on my first patrol and also learned the intricacies of defensive fire (DF) and DFSOS (defensive fire save our souls) fire tasks. Our equipment was vastly superior to anything issued in Australia. Our MGs were British and these used MK VIII Z .303 ammunition which attained a range of over 4000 metres. British clothing for cold and wet weather was comprehensive, from string singlets to ‘long Johns’, waterproof trousers, flannel shirts, wind smocks, parkas, long gloves, boots CWW (cold weather, wet) and of course the ubiquitous balaclava. This latter item, in some individuals, concealed ‘choofer’ neck. ‘Choofers’ were the oil or petrol-fired small heaters we had in our bunkers. The soot was all pervading and some of the fellows if not watched, would only wash hands and face in the morning. When forced to divest themselves of the balaclava one was presented with a pale oval in an otherwise dark background.

During our time on the Kansas Line the commander of No. 4 Section (Ray ‘Gunner’ Stevenson) and I were sent over to the battle school at Haramura for a two-week MG/fire controller course. We had flown to Japan by RAAF C–47 but on the way back the OC 1 RHU (Reinforcement Holding Unit), Kure (Major Jack Gerke) decreed that Ray and I would be the escort to the food parcels (RSL, Age etc.) for 1 RAR and 3 RAR. We were placed aboard an old steam vessel at Kure and sailed via Shimonoseki (for coaling) to Pusan. Here we supervised the off-loading and loading into rail wagons and then were ordered into a wagon with ‘C’ rations, jerry cans of water and a crate of Asahi beer for the trip to Tokchon. This took four days as we had no priority and were occasionally shunted off to make way for troop/supply trains. At Taegu the beer ran out. A friendly US MP resupplied us by breaking open a US wagon and providing a carton of Budweiser. We safely delivered all parcels to unit transport and personally accompanied the 1 RAR share to B Echelon where the QM, Captain Henry McDermott, accused us (in jest, I’m sure) of having eaten our quota en route.

Aspects that remain in my memory are of exercising in the area of Kamaksan, where the Gloucester Regiment had made its stand in April 1951. Afterwards we section commanders joined the advance party of the battalion to relieve the 1st Leicesters in 29th Brigade at Wanjing-Myong, North Korea. It was an eye-opener to join them on Hill 217 (which was to be occupied by our B Company). There we were to have a two-MG section position under the command of platoon HQ. Bill McDonald (later 3 RAR and 8 RAR) had the other section and we were very pleased to see that while the British had inferior rations this was compensated for by having a company canteen right there in the line! In our few days there we were privileged to assist and observe the 1st Leicesters support the 1st Welch in an assault on Hill 227. We also had a taste of RCL fire as the receivers. The task of the 1st Leicesters was to support a tank assault on the features forward of Hill 210. Trenches had been prepared forward and to these we went with two sections of their MG platoon. The opposition took umbrage at the efficiency of the 1st Leicesters MG and engaged us with rocket launchers. Very disconcerting!

Our soldiers in Korea really did perform well. Constant patrolling, extremes of temperature (down to –15 degrees Fahrenheit), the terrain, heavy shelling and protracted periods on largely American ‘C’ rations were a strain. The temperatures were so extreme that soldiers of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Island descent were permitted to return to Japan for the winter. I’m not sure that many did. Certainly Corporal C. Mene, who was later in my section and a Torres Strait Islander (ex-2/33rd Battalion) did not. Keeping clean was another problem as all water had to be portered up to positions (bear in mind that the features referred to are in metric terms, for example Hill 210 metres). Winter was the great test. The fierce winds from Manchuria, snow, cumbersome clothing, and oil and water that froze, needed great dedication to combat. Oil, ‘low cold test’ was used on weapons and equipment, and glycol in radiators and water jackets of MG.

Keeping fit, too, was nigh impossible for some. MG sections were stationary whilst rifle sections were constantly on the move patrolling etc. Keeping active was difficult for us. For large parts of the time it was a case of 50 per cent stand-to from dusk until prior to first light. At night we usually had either a fixed program of targets to engage, or alternatively on an opportunity basis from targets previously recorded. By day it was time for clean-up and maintenance, posting of lookouts and rostered sleeping. Sometimes there would be the need to contribute to work parties or to conduct allotted duties such as minefield checks. Occasionally the opportunity to bathe arose. I can clearly remember walking half of my section down from Hill 355 in the winter to have a bath and change of clothing. The effort in scambling down and back again was agonising. It was a case of ‘lolly legs’ and much sweating.

Our platoon had the honour of first engaging the enemy. In fact, it was from our two-section position on Hill 217. The lookout had spotted a Chinaman on the forward slope of Hill 227. Rusty Churches took up position on one gun and Bill McDonald on another and with me correcting fire we engaged him. It was successful, I think; if not our target got a fright. From that same location we later supported A Company’s assault on Hill 227.

Australian troops advance across snow-covered fields. Cold weather was a constant trial for the regiment during three winters in Korea (AWM photo no. HOB 2146).

This was Operation Blaze. Led by Major D.S. Thomson and including such worthies as CSM ‘Matey’ McLachlan, DCM, Lieutenant Gil Lucas, Corporal Harry Patch, Corporal Charlie Mene, Corporal ‘Squizzy’ Taylor (later QM 4 RAR), they assaulted in copybook fashion, two platoons up. The Company Headquarters was led by Private ‘Jock’ Burgess blowing lustily on his bagpipes. Jock kept on playing during the fight on the hill. Elements of Suppport Company and HQ Company were also there, as were 4 Section, MG Platoon (Sergeant Ray ‘Gunner’ Stevenson) with flame-throwers, assault pioneers with beehive charges etc. a line-laying party from signals and of course stretcher-bearers. There were a number of decorations awarded for the day.

Also from this hill I saw my second plane shot down. The first time had been as a boy in Scotland when I saw a German reconnaissance plane pursued and shot down by a Spitfire. On this occasion a USAAF fighter was strafing with napalm and on his climb away from the target was hit by concentrated ground fire. I’ll never forget the explosion and then the debris falling like tinfoil, turning and reflecting in the sun.

At a later time we relieved the KOSB at Naechon, North Korea, having in turn been relieved by the 1st Black Watch on Hill 217. We were now serving with 28th Brigade. We had had one day in bivouac in between and this gave the RSM time to get his senior NCOs together. Bill McDonald and I were two of the new sergeants and had our indoctrination to the mess in a squad tent. The KOSB position was really substandard, certainly from a MG point of view. Initially our guns were positioned in open trenches, rather than the sophisticated gun pits we were trained to construct. One burst of shellfire buried one of my guns and severely damaged the tripod. In fact, the living bunkers were not well constructed and in monsoonal conditions over 100 collapsed in the battalion with one soldier losing his life.

It was therefore decided to prepare new positions for two MG sections behind the forward companies but in front of the reserve, again under command of platoon HQ. This was done each night after dark for a couple of weeks. We (2 and 3 Sections) drove some distance in blacked-out jeeps, worked for most of the night, camouflaged the workings and then returned to our operational position. The big night arrived when all work was complete. We made a studied occupation by night and the following morning were welcomed by an artillery bombardment. We hadn’t fooled ‘Charlie’ after all.

In fact, in that position we had our fair share of enemy shellfire. Also, ironically, we were actually behind our 3-inch mortar platoon position. The reason was that their range was 2700 metres while ours was 4500 maximum. In this location we

Machine-gunners Private C.J. Cornell (left) and Corporal P.B. McGrellis of 3 RAR clean their Vickers machine-gun in preparation for a busy night giving fire support to patrols from the battalion (AWM photo no. HOBJ 3290).

mounted a one-man patrol! One night a noise was reported forward of our position. Captain East sent for me and giving me his .38 Smith & Wesson revolver sent me forward to investigate. There had been some instances of infiltration from the enemy. It was a long period in pitch black conditions before I eventually completed crawling forward to the reserve company listening post. After some mutual surprise we opined that it must have been an animal.

The track from the feature back to the reserve company was in enemy view and sometimes he would engage soldiers in transit with artillery fire. We sometimes had a fresh meal forward of the position on the mortar base plate position. ‘Charlie’ watched this for a time then one day caught a group of us in the open. Some got under cover. Bill McDonald and I were in the middle of the paddy but found ‘shelter’ under blades of grass. It’s amazing how comparatively safe one can be in the prone position!

Discipline was never really a problem as each person knew how much each depended on the other. Of course trench life had its pressures and minor infractions had to be dealt with immediately. There was no time for the niceties of orderly room procedure. A recourse to the threat with whatever was handy, shovel or spare Vickers barrel, was sufficient to get the message across. In D Company there was one incident where a large Scotsman pursued his section commander with a Bren gun, firing from the hip. The corporal went hurtling through the trenches and, knowing he was in considerable peril, snatched a 36M grenade from the ready-use box and threw it behind him. The Scotsman was stopped. After hospitalisation in Australia he was deported. The corporal was court-martialled and gaoled. To this day I consider that a miscarriage of justice.

Our creature comforts were reasonably well catered for. Cigarettes were free. There were UK-issued Woodbines etc. supplied by Lord Nuffield, and of course there were Camel and Lucky Strike, which came with US ‘C’ rations. we received the RSL or Melbourne Age food parcels I previously mentioned. When possible a beer ration came forward. This was Japanese Asahi, Kirin or Nippon bottled beer. It came in wooden cases, each bottle wrapped in straw. I think we paid a shilling a bottle and in winter one had to thaw the bottle on a stove! When not obtainable we blamed (possibly not always inaccurately) the ‘Q’ staff for using it for barter with the Americans. In winter a rum ration was issued. Officers and WO/SNCOs were permitted to purchase one bottle of spirits per month.

I have mentioned artillery sniping on open tracks. One feature in Korea was the use of extensive camouflage near the front. Cuttings and other exposed parts of roads had huge camouflage nets erected to conceal truck movement from enemy view. Naturally it did not stop shell and other fire but tended to reduce the incidence.

I do not recollect that there was any censorship in Korea although there was a strict search of soldiers going on patrol to ensure they weren’t carrying letters, diaries marked maps and such. This was all part of a comprehensive rehearsal for each patrol. For corresponding with relatives there were message cards available where one deleted lines not required. Ideal for the busy soldier, to reduce a message to something like ‘I am well, thinking of you—love etc.’!

The MG platoon was the source of the raw material for many of the beds in the battalion. The Vickers used 250-round stripless heavy cotton belts and these were used in conjunction with steel pickets to construct double bunks in bunkers. These bunkers were home for protracted periods and had to be kept very tidy to avoid disease etc. We had a rat problem and occasionally one would hear illegal gunshots as some individual, driven to desperation used his Owen or pistol to despatch some ugly rodent. One night ‘Rusty’ Churches awoke from what he though was a pleasurable dream to find a rat licking his (Rusty’s) lips! He had eaten a juicy Canadian apple just before going to sleep.

It was after this period in the line we had the opportunity to regroup and enjoy some sergeants’ mess activity in reserve at Yong Dang, North Korea. They were a great group of SNCOs, many of them either ex-2nd AIF or British Army of Second World War vintage. Some names that are perhaps familiar are RSM Wally Smith (now Hunt-Smith), Paddy Brennan, Frank Deane, Des Corcoran (later Premier of South Australia), Sam Beam, Ernie Giffen and Stan Nietschke. It was a great time to tell lies and enjoy Asahi beer.

Soon the 1st Battalion, the Royal Canadian Regiment (1 RCR) were in trouble at Hill 355 (Kowang-San), the ‘Divisional Vital Ground’. Their forward company was overrun. Initially we had word that we would have to counterattack but 1 RCR handled it themselves and we relieved them in due course. It took the battalion a deal of time to wrest back control of the valley floor by aggressive patrolling and use of fire. We played our part in the scheme of things and sometimes assisted greatly in restoring the balance.

Three incidents I remember vividly were Operation Fauna, the Burns–Boyd patrol clash and a South Korean battalion-strength fighting patrol. Fauna was a company-strength deep penetration fighting patrol, onto feature ‘Flora’, led by Major A.S. ‘Joe’ Mann, B Company. They had assault support at the rapid rate, once the company was committed; prior to that we engaged in our normal harassing fire program. We used vast quantities of ammunition that night because we had a huge surplus left behind by 1 RCR. They had given their Vickers a holiday on site and used .5 HMG. We changed barrels at least once on each gun. Anyway at one point a Chinese HMG engaged B Company and we could see the tracers. Our CO, Lieutenant Colonel M. ‘Bunny’ Austin (he had relieved Hutchison at the halfway point) spoke to me by land line and asked me to try to neutralise it. At extreme range and unrecorded, I made a guess using hand angles against the silhouetted skyline and adjusted fire at the rapid rate. The HMG desisted but I will never know whether we were successful or he ran out of ammunition.

We in turn were receiving attention from the opposition as they tried to reach us with artillery. Fortunately they did not have our range although the gun crews (Roy Anderson, Bob Gow, Peter Roberts and Merv Kimler) complained of shrapnel entering the gun pits. The pits had cavernous openings designed for .5 calibre Browning HMG. We had not been able to adapt them satisfactorily.