2

2

A Cautionary Tale: Drug Company Influence

A MAJOR SOURCE OF CONCERN ABOUT THE EFFECTS OF FOOD-INDUSTRY sponsorship is what we know about the consequences of funding by other industries, particularly those involved with tobacco, chemicals, and pharmaceutical drugs. Decades of books, reports, reviews, and commentaries describe how these industries influence research and opinion. One search, just for studies or reviews of the effects of industry funding since the 1970s, identified about eight thousand items. Of these, only a handful were about funding by food companies (food-industry funding is a relatively new area of interest). But regardless of the industry, these studies come to similar conclusions. All industries making products of questionable health benefit exert influence by diligent adherence to strategies—collectively referred to as the “playbook”—first established to great effect by tobacco companies and recently described in detail as a set of political and legal tactics to influence policy and shape public perceptions and to obtain research that helps with such efforts.1

As early as the 1950s, tobacco-industry executives were well aware of evidence linking cigarette smoking to lung cancer. Nevertheless, they embarked on campaigns to cast doubt on that science and to deny that cigarettes were harmful. The playbook required executives to repeatedly deflect attention from diseases caused by cigarettes, to neutralize criticism, and to undercut calls for regulation. The playbook demanded endless repetition of carefully crafted statements: cigarette smoking is a matter of personal responsibility, government attempts to regulate tobacco are manifestations of a “nanny” state, restrictions on smoking infringe on freedom, and research reporting harm from smoking is “junk science.” Let us credit the tobacco industry for producing the model now followed by other industries, the food industry among them.2 Whatever the industry, the playbook requires repeated and relentless use of this set of strategies:

Cast doubt on the science

Cast doubt on the science

Fund research to produce desired results

Fund research to produce desired results

Offer gifts and consulting arrangements

Offer gifts and consulting arrangements

Use front groups

Use front groups

Promote self-regulation

Promote self-regulation

Promote personal responsibility as the fundamental issue

Promote personal responsibility as the fundamental issue

Use the courts to challenge critics and unfavorable regulations

Use the courts to challenge critics and unfavorable regulations

For our purposes, the closest example of the playbook in action is its use by the pharmaceutical (“drug”) industry. This industry’s adoption of the playbook was so successful that by the early 1990s medical ethicists were dismayed to observe that nearly all medical specialties and subspecialties were rife with conflicts of interest.3 Today, the conflicts created by drug-industry practices have been thoroughly recognized and thoroughly documented. Most relevant is the way this industry—pejoratively, “Big Pharma”—induces physicians to prescribe brand-name drugs and funds research to demonstrate the superiority of brand-name drugs over generics. Also relevant are the increasingly insistent demands to curb this industry’s most egregious practices. Current drug-industry policies and regulations may be less than fully effective, but they demonstrate that the medical profession has long recognized the risks of this industry’s influence and has taken steps to prevent or mitigate those risks.

I personally encountered the playbook actions of Big Pharma in 2005 when the American Diabetes Association invited me to speak about dietary aspects of that disease at its annual meeting. In browsing through the program book, I was surprised to see so few sessions dealing with nutrition issues. I could find only one other—a session on sugars and health organized by Oldways Preservation & Exchange Trust (a group we will meet again) that was sponsored by Coca-Cola. The session description included this statement: “Diets based on demonizing any one food, including sweetness and sugars, are diet plans that are doomed to fail; the issue is portion control.”4 Yes, it is, but this session seemed designed to reassure diabetes specialists that their patients could drink Coca-Cola with impunity.

In my talk, I showed a slide illustrating a recently approved injectable diabetes drug with the brand name Byetta (exenatide), extracted from Gila monsters. Injections? Gila monsters? Surely eating vegetables and losing a few pounds would be a better approach to preventing type 2 diabetes. But members of the audience chided me for questioning the value of a drug that could help patients control blood-sugar levels. This too surprised me. I assumed that this audience knew as well as I did that losing weight—often just a few pounds—can reverse symptoms of type 2 diabetes in many patients.5

But then I went to the exhibition hall. Acres of exhibit space were packed to the walls with booths marketing one drug after another. I trekked the aisles collecting the free swag—the “brand-reminder” items distributed at every booth. These ranged from small things like pens, prescription pads, and squeeze toys to more expensive ones like lab coats, stethoscopes, medical bags, and textbooks. As I will soon explain, it is well established that even small gifts induce doctors to prescribe the donor company’s specific products.

Drug companies spend fortunes on brand-reminder items, but they spend even greater fortunes on personal visits from representatives, continuing-education courses, meals, and vacations—all aimed at influencing prescription practices. As early as the 1970s, critics were writing books about drug-company spending to “reach, persuade, cajole, pamper, outwit, and sell” to doctors. Most of the money went for detailers—the men (and later women) who visited doctors’ offices to explain the benefits of their employer’s drugs and to drop off gifts. Even then, community and hospital pharmacists could tell when detailers had visited by the sudden increase in prescriptions for specific brands of drugs. Drug advertisements in the American Medical Association’s journal accounted for half its income, perhaps explaining why this group was not complaining about drug-industry marketing practices.6

The most obvious explanation for the size and extent of the literature on drug-industry practices is that this industry’s interactions with physicians are easily measured: by the monetary value of the gifts and payments, of course, but also by their effects on recipients’ prescription practices, votes on drug-advisory committees, and research results. Other effects are also measurable but with more difficulty: unnecessary treatment of patients, higher health care costs, and loss of trust in the medical profession. By analogy, all these findings are relevant to the less well studied influence of food companies. For any industry, the starting point for analysis of funding influence is what psychologists have learned about how gifts affect human behavior.

The Psychology of Gifts

You might think, as I did before researching this book, that gifts are no big deal. You give presents and you receive them (happily or not), you thank the donor, and that is the end of it. But psychologists who study the effects of drug-industry gifts to physicians—and many have—remind us that doctors are human and that much of what humans think and feel occurs subconsciously. All of us, including doctors, respond to gifts in predictable ways. But—and this is critical—our responses are usually unintentional, unconscious, and unrecognized. No doctor intends to be beholden to a drug company, yet even a small gift is enough to change prescription practices in the donor’s favor. Larger gifts have even greater influence. Despite this evidence, recipients—human as we are—believe that gifts and payments from drug companies have no influence.7

These conclusions derive from experimental studies in psychology, neurobiology, and behavioral economics; these demonstrate that even recipients with honest intentions respond predictably to gifts and payments but are unaware of doing so. Drug companies do not “buy” physicians. Physicians do not “sell out” to drug companies. The influence is far more subtle, making it exceptionally difficult to prevent or manage—or even to discuss. If recipients do not believe they are influenced by gifts and payments, they see no reason to refuse them.8 It is not that doctors are necessarily corrupt; it is the system that is corrupting.

Pharmaceutical companies are in the business of selling drugs. They want doctors to prescribe their brands rather than those of competitors, generics, or over-the-counter products, even when those alternatives might be better tested, more effective, and less costly. They pay physicians to consult for them, speak on their behalf, and serve on their committees or boards, and they offer free registrations at conferences (often at resorts), travel expenses, and meals. Figure 2.1 satirizes the way the system works.

Ethically minded physicians, concerned about the effects of these practices on health care costs, risks to patients, and trust in the profession, demanded regulation. They lobbied Congress to require public disclosure of drug-industry gifts and financial ties to doctors. Despite industry opposition, Congress finally agreed and passed the Physician Payments Sunshine Act as part of the Affordable Care Act in 2010. The result is the Open Payments website, where you can easily discover that in 2016, 1,479 pharmaceutical companies spent $8.19 billion on payments of one kind or another to 631,000 physicians and 1,146 teaching hospitals. About half the total expenditures went for research, leaving the remaining half for reaching physicians in other ways.9

FIGURE 2.1. Drug company gifts—small branded items, consulting fees, conference registrations, and meals—induce physicians to prescribe the donor’s specific products rather than less expensive and sometimes safer and more effective alternatives. ©Steve Kelley Editorial Cartoon, used with the permission of Steve Kelley and Creators Syndicate. All rights reserved.

The results of drug-industry spending are well established. By the early 1990s, researchers could already show that a free trip to an industry-sponsored conference doubled the prescription rate for the sponsor’s product. In 2000, a review of more than five hundred studies found that industry gifts, meals, travel funds, and detailers’ visits correlated strongly with prescription of brand-name drugs rather than less expensive or more effective alternatives.10

Open Payments makes such studies easier to do and more accurate. In 2015, researchers found that nearly half of all US physicians accepted payments from industry, adding up to $2.4 billion. A study of statin prescriptions the following year yielded a formula: for every $1,000 received from drug companies, the prescribing rate for brand-name statins increased by 0.1 percent; payments for educational training led to a 4.8 percent increase. Investigators concerned about the health crisis caused by overuse of opioids found that from 2013 to 2015, one in twelve American doctors received payments—more than $46 million—from drug companies selling these drugs.11

One especially troubling observation is how little it takes to exert this influence. Brand-reminder pens and prescription pads induce changes in prescription rates, as do drug samples. Visits from detailers are particularly effective, which is why many teaching hospitals now ban them. Payments for speaking or consulting also work splendidly. So do meals; these are now the most frequent kind of drug-industry gift, with a median value of $138 each (one hopes wine is included). But even meals costing as little as $13 correlate closely with higher prescription rates—and for months afterward. Investigative journalists at ProPublica used Open Payments data to demonstrate a dose-response relationship between the size of drug-company payments and prescribing practices. Overall, the link between drug-industry gifts and prescription practices is so firmly established that it is considered beyond debate.12

Equally disturbing is the widespread willingness to accept such gifts. In 2009, nearly 84 percent of physicians reported receiving gifts or payments from drug companies; cardiologists were especially welcoming targets. Yet when asked, 90 percent of physicians who accept drug-industry funding deny its effects and say they base their prescribing habits solely on clinical knowledge and experience. Research shows otherwise. Recipients remain loyal to a donor’s products long after receiving payments, and the larger the gifts, the more recipients are likely to oppose measures to prevent such influence.13 No wonder drug companies spend billions to reach doctors.

Why do doctors allow this? This too has been researched. Recall that doctors are human and the influence of gifts is not always conscious; doctors believe they deserve such gifts. They went to school for years, sacrificed to get where they are, work hard, and may still be paying off student loans. They see themselves as entitled to the gifts, rational in their prescribing practices, and invulnerable to drug-industry influence. Reminding them of the sacrifices they have made actually increases their willingness to accept such gifts.14 None of this would matter if the gifts had no influence, but they do. Financial ties to drug companies not only affect doctors’ prescription practices but also influence their opinions on drug advisory committees and the conclusions of their research.

Influencing Drug Advisory Committees

If medical experts who serve on advisory committees have financial ties to products under consideration, are they more likely to recommend questionable drugs, brand-name drugs rather than generics, and wider use of drugs as treatment options? Yes, they are. By law, experts who serve on federal advisory committees are not supposed to be in thrall to special interests. Those with links to companies making products under review are precluded from serving on such committees, except when the agencies waive that rule—which they frequently have done.15

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is responsible for approving drugs. It uses about fifty committees to obtain advice from independent experts about scientific, technical, and policy matters. Many laws, regulations, and guidance documents govern potential conflicts, real and apparent, among candidates for positions on those committees. Committee members are considered “special government employees” who may not participate in matters that have direct effects on their financial interests: stock and bond holdings, consulting arrangements, grants, contracts, or employment. But because the FDA insists that it cannot find enough candidates who are not tied to industry, the laws permit waivers to candidates who have such ties, and the FDA still often grants them.16

Because so much money is involved in drug-approval decisions and because some brand-name drugs are ineffective or harmful or increase health care costs, the FDA’s policies have long troubled critics. The Open Payments website makes it possible to investigate the FDA’s committee system. Studies of votes on drug approvals find striking results: committee members with financial ties to the makers of drugs under scrutiny are far more likely to vote for approvals than are members without such ties, and some drug approvals would not have occurred if the committees had excluded the votes of members with ties to manufacturers. But the FDA ignores such evidence. In 2017 the FDA announced how it would respond to critics’ complaints: it intended to grant more waivers to committee members with financial ties to industry, not fewer.17 Statements like these make the FDA appear to be “captured” by the drug industry.

Investigators concerned about industry capture have also looked at committees issuing practice guidelines. Their studies show that members of such committees frequently receive gifts, speaker fees, and other payments from drug companies likely to be affected by their guidelines. One investigation found that 84 percent of authors of guidelines issued by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network receive such payments. Another reported that 62 percent of the members of an international consensus committee writing gastroenterology clinical practice guidelines had at least one financial tie to a relevant drug company; in this case, the experts with such conflicts recused themselves from discussions of six of the eight recommendations—a step in the right direction.18

The standard explanation for these high percentages is the impossibility of finding independent experts to serve on guideline committees. I have some doubts about this, and I also have trouble believing that recusals are sufficiently protective. In my experience, committee members want to hear each other’s opinions and can be influenced by them even when the recused individuals are physically absent from discussions of the matter at hand.

Beyond direct financial ties to committee members, drug companies have other ways of influencing decisions. One is to pay for the formation of patient-advocacy front groups to press for approval. A database established by Kaiser Health News found that fourteen pharmaceutical companies collectively donated $116 million to 594 such groups in 2015.19 In 2018, a US Senate report called for more transparency on this issue, noting that the five leading producers of opioid drugs contributed nearly $9 million to third-party advocacy groups from 2012 to 2017. Such groups, the report charged, “have, in fact, amplified and reinforced messages favoring increased opioid use.”20

My favorite example is the FDA’s approval in 2015 of flibanserin, the “female Viagra,” marketed as treating what critics believe is a nondisease: “acquired, generalized hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women.”21 On the basis of the drug’s minimal benefits and well-documented risks, FDA committees twice rejected the drug. On the third try, the maker of flibanserin, Sprout Pharmaceuticals, organized a front group, Even the Score, positioned as a grassroots feminist organization campaigning on behalf of the right of women to take this drug. The advisory committee voted for approval based on the group’s ostensibly independent advocacy. In what I see as another example of the FDA’s corporate capture, it accepted the committee’s decision even though it listed the drug’s hazards in its approval announcement and required a boxed warning label and three further studies. The Washington Post attributed the decision to Sprout’s “clever, aggressive public relations campaign” and termed it “bad news for rational drug approval.”22

Drug companies also fund patient-advocacy groups to buy silence. Funded groups rarely call for controls on drug prices, for example. Donations to such groups can be considerable; in 2015, drug companies contributed $26.7 million to the American Diabetes Association. But in this particular case, the association broke ranks and called on the federal government to negotiate with drug companies to reduce prices for Medicare patients, something that Congress, under pressure from Big Pharma, does not allow the government to do.23

When it comes to industry funding, as we will see throughout this book, the issues are never simply black or white; they are usually more complicated shades of grey.

Influencing Research

Drug companies have strong economic incentives to convince the FDA, doctors, and the public that their products do wonders for health, cause no harmful side effects, and are better than alternative remedies. In addition to funding clinical trials designed to prove safety and effectiveness, the companies fund “seeding trials”—studies aimed at marketing drugs to physicians. They pay ghostwriters to produce articles signed by authors who appear to be independent but are anything but. They withhold the results of studies that do not favor their products. They engage in selective reporting of trial outcomes.24

The most thoroughly investigated effect is the way industry-funded research almost invariably favors the sponsor’s commercial interests. Sheldon Krimsky, a Tufts University professor who studies industry manipulation of science, dates the discovery of this “funding effect” to the mid-1980s, when social scientists realized that if they knew who paid for a study, they could predict its results. One funding-effect investigation from the late 1990s looked at studies on the safety of calcium channel blockers for reducing blood pressure. Nearly all authors (96 percent) who concluded that the drugs were effective reported financial ties to their manufacturers; only 37 percent of authors who doubted their effectiveness had such ties. In 2003, a systematic review of more than one thousand biomedical research studies came to similar conclusions; investigators with industry affiliations were nearly four times more likely to come up with pro-industry conclusions than those without such ties.25

Since the mid-1990s, Lisa Bero’s research group, now at the University of Sydney, has produced evidence that industry-funded studies generally favor the sponsor’s interests. Other groups have confirmed this work, and new confirmations appear regularly. Their findings: research sponsored by drug companies generally favors newer—and more expensive—drug treatments. Research funded by a drug company alone is likely to be more biased than research sponsored by a drug company plus any other sponsor. If the results of studies sponsored by drug companies produce unfavorable results, they are less likely to be published. With respect to drug studies, the idea that industry funding distorts the outcomes of research seems beyond dispute.26

But how does this happen? Recall: recipients of industry funding do not recognize its influence and typically deny it. For approval, a drug company only has to prove that its products are reasonably effective and safe; it does not have to compare the drug to generics or competitive products. Although preliminary research might have eliminated less effective drugs, that is not enough to explain the consistency of the funding effect.

A more realistic explanation is the ease of designing research to obtain a desired result, whether consciously or unconsciously. All it takes is to leave out appropriate comparisons and put a positive spin on results that do not show an effect. Bero’s group has demonstrated that five industries, pharma among them, selectively fund research that supports industry objectives, manipulate research questions to obtain desired results, and suppress research with unfavorable results. Funding source, Krimsky suggests, may not be definitive evidence of bias, but it should strongly suggest the possibility of bias. Intentionally or not, drug-industry funding drives the research agenda, confuses the science, and fuels public distrust. At issue is what to do about it. A recent study suggests that journal editors cannot be counted on to pay much attention to research bias; half the editors of leading US medical journals received payments from drug and medical-device companies.27

Managing Drug Industry Influence

The influence of drug-industry gifts and payments is so measurably blatant that it cannot be ignored. But what to do? If you view doctors’ financial relationships with industry as flat-out corruption, then obvious solutions are education programs about conflicts of interest, restrictions on gift size, codes of ethics, and disclosure of industry contacts. These help, but the issues are invariably more complicated. When industry influence is unconscious, unrecognized, or denied, these methods cannot be effective. Indeed, their imposition can result in perverse effects, causing recipients to believe even more strongly in their personal immunity to any influence. For this reason, some experts on this topic argue that there is only one way to deal with the conflicts of interest induced by industry gifts and payments: ban all such gifts and payments.28

For decades, medical leaders have tried to encourage policies in that direction. In 1984, Arnold Relman, then editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, broke new ground by requiring authors to declare conflicts of interest. A year later, he called on physicians to remove themselves from the medical marketplace and put the interests of patients first. And a decade later, the American Medical Association, finally taking up this issue, observed that drug-industry gifts were creating three hazards: influencing physicians, giving the appearance of impropriety, and increasing drug costs to patients. It argued for a new policy: physicians should accept only gifts that directly benefit patients and are of minimal value.29 But as we have seen, even small gifts exert influence.

With no evident improvement in drug-industry practices, Congress became concerned about the integrity of federally supported research. In 1995, it established standards to ensure that research design, conduct, and reporting would not be biased by conflicting interests resulting from financial ties to corporations. Congress required recipients of research grants to disclose such ties, which it specified as salaries, consulting fees, honoraria, stocks, patents, copyrights, or royalties. Congress stated that conflicted researchers should, if necessary, modify their research plans, end their participation, or divest their conflicted holdings.30 It applied these guidelines to all research, including nutrition research.

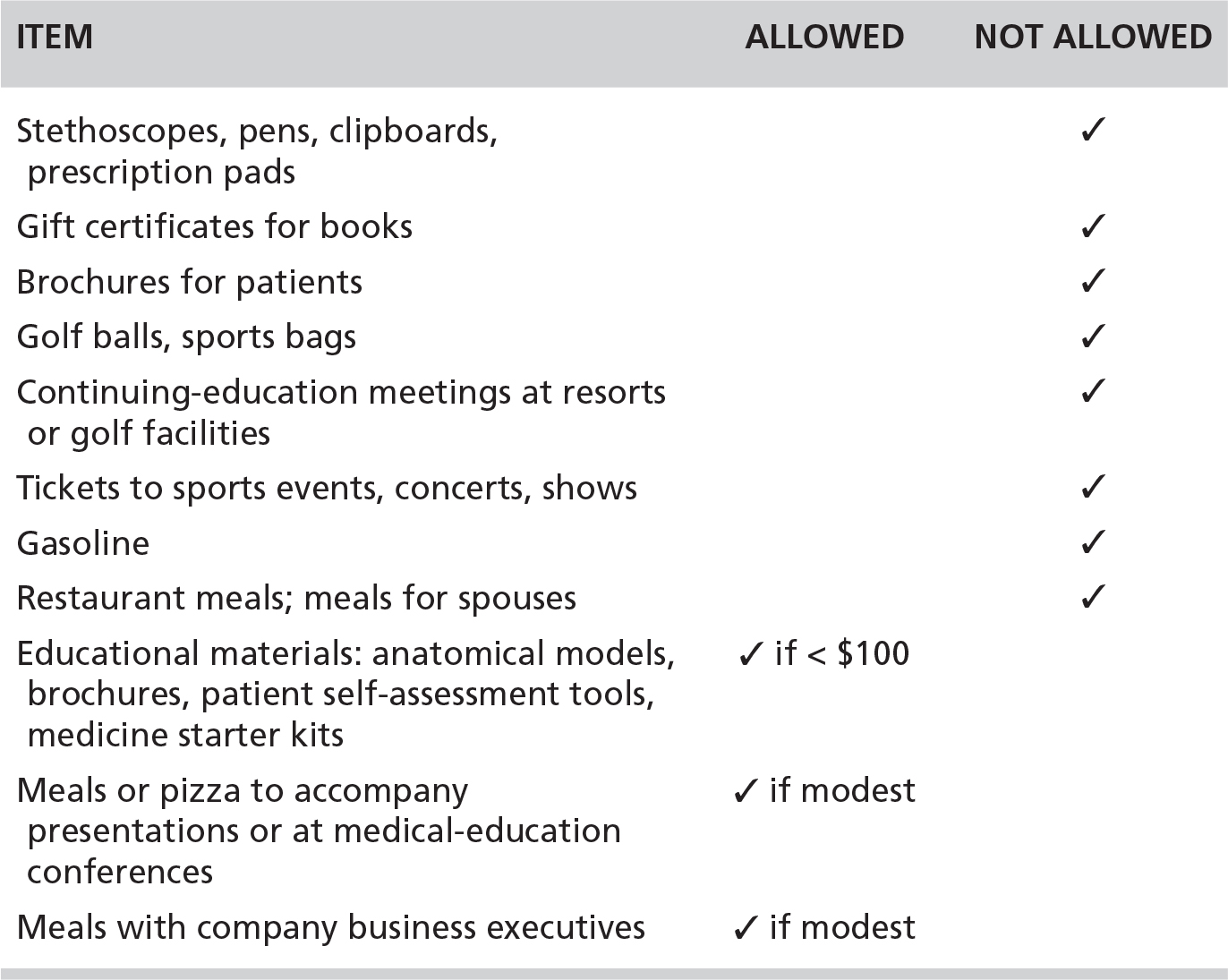

In 2009, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), the industry’s trade association, issued a code for interacting with health care professionals, an action that appeared to be designed to head off federal regulation. In deciding what drug company representatives—the detailers—could and could not give to physicians, PhRMA proposed that the gifts ought to benefit patients or contribute to medical education.31 Table 2.1 summarizes some of its guidelines. These are revelatory about now-forbidden practices that were common prior to 2009 and about potential loopholes, such as the meaning of “modest.”

Despite these guidelines, Congress passed the Physician Payments Sunshine Act the following year. Some of the pressure for its passage came from medical professionals such as Jerome Kassirer, who had just stepped down as editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. In his words, “Deans of medical schools and training program directors must do a better job of addressing conflict of interest. Where professionalism is concerned, they must teach that there is no free lunch. No free dinner. Or textbooks. Or even a ballpoint pen.”32

TABLE 2.1. The Pharmaceutical Industry’s 2009 Guidelines for What Companies May and May Not Give to Physicians (Selected Examples)

In 2013, a task force sponsored by the Pew Charitable Trusts recommended best practices for physicians engaged in medical education. These included a requirement for disclosure of industry ties but also outright bans on accepting industry funding for speaking, writing, or education; for gifts or meals; or for consulting and advising relationships. More recently, Robert Steinbrook, an editor at large for JAMA Internal Medicine, pointed out the “inherent tensions between the profits of health care companies, the independence of physicians and the integrity of our work, and the affordability of medical care.” He noted, “If drug and device manufacturers were to stop sending money to physicians for promotional speaking, meals, and other activities without clear medical justifications and invest more in independent bona fide research on safety, effectiveness, and affordability, our patients and the health care system would be better off.”33

Despite evidence that drug companies readily find ways around restrictions on gifts and payments, they and their beneficiaries continue to deny its influence and oppose regulation. In 2016, nearly one hundred US national and state medical societies supported a Senate bill, the Protect Continuing Physician Education and Patient Care Act, that would exempt medical drug and device makers from having to report payments made to doctors for continuing medical education, medical journals, or textbooks.34 With powerful forces lobbying to continue business as usual, the medical profession still has a long way to go to address industry-induced conflicts of interest, even when those conflicts—and the harm they cause—are thoroughly documented.

Dealing with the effects of industry funding on food and nutrition professionals is even more difficult, in part because the effects are far more difficult to measure. As we see next, only a few studies to date have examined the influence of food companies on nutrition research.