9

9

Co-opted? The American Society for Nutrition

NUTRITION PROFESSIONALS ALL OVER THE WORLD BELONG TO societies focused on research, education, and practice, many of which accept sponsorship by food, beverage, and supplement companies. In the United States, nutrition scientists and medical nutrition researchers generally belong to the American Society for Nutrition (ASN), nutrition educators to the Society for Nutrition Education and Behavior (SNEB), and dietetics practitioners to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND). Other national nutrition organizations tend to represent more specialized interests. The Obesity Society, for example, represents medical and health professionals who treat that condition; its website promotes its “longstanding history of mutually beneficial partnerships with industry.” Two much smaller nutrition societies deserve special mention for their unusual refusal to accept industry funding: the 1,400-member American College of Nutrition, which focuses on the application of research to clinical practice, and the World Public Health Nutrition Association, which has about 500 members.

Food companies support nutrition societies by helping pay for conference activities, publications, prizes, and scholarships. In return, they gain goodwill and what CSPI calls “innocence by association.”1 In their capture of nutrition organizations, food, beverage, and supplement companies participate in the increasing influence of corporations over American society.

Such effects are evident from two studies published in 2016. The first pointed out that at the same time that soft-drink companies were sponsoring the health-promoting activities of ninety-five health organizations, they were also lobbying against public health measures such as soda taxes. The second found evidence for substantial influence by corporate sponsors over the scientific program of a nutrition conference in Brazil; speakers who discussed promotion of healthful diets, for example, did not recommend avoiding unhealthful food products but instead called for motivating individuals to make better food choices. For such reasons, some experts view food-industry sponsorship of nutrition societies as “preposterous” and as creating “unfathomable” risks. Nutrition societies, they insist, must be transparent and accountable for how they get and use funds from food, drink, and other industries and for how those industries might affect their work.2

ASN is a good example of how food industry sponsorship produces troubling effects. It is the principal US association for doctoral-level academics and physicians who conduct nutrition research. It has about six thousand members (including me). Its very mission includes industry: to bring together “the world’s top researchers, clinical nutritionists and industry to advance our knowledge and application of nutrition for the sake of humans and animals.”3 The society holds conferences, gives awards, and publishes four research journals, and it actively seeks food-industry donations for such activities.

ASN has a complicated history. It was formed in 2005 through the merger of three older societies: the American Institute of Nutrition (AIN—established in 1928), the American Society for Clinical Nutrition (established in 1961), and the Society for International Nutrition (established in 1996). The oldest, the AIN, was founded in the 1920s to represent some of the first researchers engaged in identifying and characterizing the newly discovered vitamins and minerals. Their experiments, which often involved feeding diets of defined composition to rats, dogs, or chickens, appeared to constitute an entirely new field of study, one that called for its own professional society and journal. These scientists formed the AIN expressly to publish a journal to share research results—then and now the Journal of Nutrition. A history of the AIN published in 1978 mentions industry sponsorship in only one context, annual awards beginning in 1939 from Mead Johnson and in 1944 from Borden Dairy.4

In the early 1950s, medical researchers with interests in human—as opposed to animal—nutrition began publishing their own, clinically focused journal (now the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition) to compensate for the lack of nutrition education in medical schools.5 In 1961, they formed a separate organization, the American Society for Clinical Nutrition, as a division of the AIN. Five years later, this society established its own industry-funded award, a gift from the Dairy Council to honor Elmer McCollum, the scientist who in 1912 had codiscovered vitamin A in milk. McCollum gets credit as the force behind the formation in 1915 of the National Dairy Council, that industry’s principal trade association. The Dairy Council paid for publication of the AIN’s 1978 history.

In 1968, the Journal of Nutrition began to list the AIN’s corporate sponsors in every issue. The first sponsors included twenty-six companies, among them Coca-Cola, Hoffman–La Roche, Monsanto, Nestlé, Procter & Gamble, and Ralston Purina. The American Society for Clinical Nutrition began to list sponsors in 1979, when there were thirteen, mostly drawn from the same of companies sponsoring the AIN. Since the 2005 merger, ASN has represented researchers of all types: basic, clinical, and applied. Table 9.1 lists ASN’s corporate sponsors in 2018. The society’s journals list them with this introduction: “Industry organizations with the highest level of commitment to the nutrition profession are recognized as ASN Sustaining Partners. ASN is proud to partner with these companies to advance excellence in nutrition research and practice.”

TABLE 9.1. The American Society for Nutrition’s Sustaining Partners, 2018

Abbott Nutrition

Almond Board of California

Bayer HealthCare

Biofortis Clinical Research

California Walnut Commission

Cargill

Corn Refiners Association

Council for Responsible Nutrition

Dairy Research Institute

DSM Nutritional Products

DuPont Nutrition & Health

Egg Nutrition Center

General Mills Bell Institute of Health and Nutrition

Herbalife/Herbalife Nutrition Institute

International Bottled Water Foundation

Kyowa Hakko USA

Mars

McCormick Science Institute

Mondelēz International Technical Center

Monsanto Company

National Cattlemen’s Beef Association

Nestlé Nutrition, Medical Affairs

PepsiCo

Pfizer

Pharmavite

Tate & Lyle

The a2 Milk CompanyTM

The Coca-Cola Company

The Dannon Company

The Sugar Association

Unilever

In April 2016, I spoke to ASN’s newly formed “blue ribbon” Advisory Committee on Ensuring Trust in Nutrition Science (the Trust Committee) about the risk of bias associated with industry funding. The need for this committee had become increasingly apparent. The previous year, Michele Simon, the supporter of plant-based diets who wrote the report about the USDA’s sponsorship of dairy foods discussed in Chapter 5, published the results of an investigation of ASN’s collaboration with the food industry. The title of her 2015 report aimed straight at the reputational risk: “Nutrition Scientists on the Take from Big Food: Has the American Society for Nutrition Lost All Credibility?” Its sponsor was the Alliance for Natural Health, a group in favor of approaches to health that incorporate functional foods (those formulated for health purposes), dietary supplements, and lifestyle changes.

Simon’s report listed ASN’s industry donors, described their influence at annual meetings and on policy statements, and exposed conflicts of interest resulting from members’ financial ties. In response to these and other concerns about its sponsorship policies, ASN asked the Trust Committee to “establish recognized best practices that allow collaboration across industry, government, academia, and nonprofit, nongovernmental organizations… leading to the best science and policy possible, attained with the highest level of rigor, transparency and confidence.”6

Pulling this off would be challenging given ASN’s history of industry ties, but I thought appointment of the Trust Committee was an impressive step, especially because its members were distinguished experts in nutrition science, public perception, and conflicts of interest. If any group could rise to the challenge—create a policy that allowed industry funding but protected integrity—this one could.

I hoped the committee would deal with the question of whether industry sponsorship of ASN was even necessary. As a member in 2017, I paid annual dues of $190 (which included online journal subscriptions) and a registration fee of $420 for the annual meeting (which did not cover travel, hotel, or meals, and increased to $500 for the 2018 meeting). I asked the society’s executive director, John Courtney, how much of its work is supported by the Sustaining Partners. He told me that they cover less than 4 percent of ASN’s annual budget and that industry contributions are earmarked specifically for professional development, student prizes, and the like. ASN, he said in an email, “is a small player when it comes to receiving industry funding compared to others in the nutrition space.”7 Then why take the reputational risk?

ASN, he explained, “is a welcoming ‘big tent’ where all stakeholders in the nutrition research enterprise can participate, share latest research information, dialogue and debate, and develop relationships to advance the field and members’ careers.… Many of our academic members value the opportunity to meet with industry counterparts as a growing number of graduates are being employed in the private sector and a growing portion of the total nutrition research funding comes from this sector.” The ASN leadership believes that it should “welcome and convene all of the stakeholders and voices in the nutrition field to meet, discuss, share perspectives, and learn from each other in our quest for advancing global public health through the best nutrition science and practice.”

Welcoming sounds good, but the society’s “big-tent” approach makes it look like an arm of the food industry rather than an independent voice in debates about nutrition issues. ASN has a long history of allowing food companies to sponsor its conferences and symposia and of appearing to promote food-industry interests over those of public health. In Food Politics, I wrote about an ASN meeting in 1999 at which I went to a particularly memorable Kellogg-sponsored breakfast meeting for heads of university nutrition departments. It featured samples from the company’s proposed line of foods with psyllium fiber, then undergoing test-marketing (they failed and soon disappeared). The Dairy Council and the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association also sponsored sessions at that conference. This tradition continues. Kellogg still sponsors breakfasts; the one in 2017, which I did not attend, was listed as featuring a discussion of trust in nutrition science among other topics. Industry-sponsored sessions were interspersed throughout the scientific program; the ones that offered lunch were especially well attended.

I was interested to see that two of the society’s most prestigious awards in 2017 went to leaders of the recently disbanded Global Energy Balance Network (GEBN); another went to a Coca-Cola executive involved with the GEBN.8 ASN committees—not the ASN leadership—choose award recipients. The members of these particular committees may never have heard of the GEBN events, or perhaps they did not view them as germane to decisions about who deserved honors. But such awards make ASN appear to be untroubled by conflicted relationships with food companies.

It is not that ASN ignores the issue. As a speaker at a session on the US dietary guidelines, I was sent a prototype slide for disclosing conflicts of interest and instructed to display that information at the beginning of my presentation. I did so, but I could see from attending other sessions that compliance with this directive was haphazard or perfunctory. Speakers frequently omitted the disclosure slide or displayed it so quickly that it could not be read.9 Judging from questions and comments after my and other sessions, conflicts of interest are a touchy issue for ASN members. Speakers and audience members commented that financial ties to food companies are either irrelevant or necessary and desirable.

Does sponsorship influence the content of conference sessions? If nothing else, sponsored sessions exclude speakers who might hold opinions contrary to the donor’s interests. ASN permits corporate sponsors to organize and run “satellite” sessions for fees that in 2018 ranged from $15,000 to $50,000 each, depending on length and time of day. The 2017 program book identified these sessions as industry-sponsored, although not always prominently, and they were fully integrated into the overall scientific program. This makes them appear to be endorsed by the society, even though ASN specifically denies endorsing the content of satellite events.

ASN hosted ten satellite sessions during the 2017 annual meeting. Sponsors included the Almond Board of California, Cattlemen’s Beef Board, National Dairy Council, Herbalife Nutrition Institute, Pfizer, Tate & Lyle, and the Egg Nutrition Center, among others. The Global Stevia Institute, for example, sponsored a session on the science, benefits, and future potential of this low-calorie sweetener. While eating a free lunch, participants could achieve the session’s stated objectives: explore the latest scientific evidence for stevia’s benefits and understand the science behind stevia’s “naturality.” Although satellite sessions look educational, they serve marketing purposes. Speakers at this particular session reviewed evidence for stevia’s benefits. Some contrary evidence exists, but participants at that session were unlikely to learn about it.10

In 2018, in what I view as a partial improvement, ASN moved most industry-sponsored sessions to the weekend before the start of the annual meeting and labeled them “Preconference/Satellite” to distinguish them from the scientific sessions. But the sponsors still included groups such as the Hass Avocado Board, the Egg Nutrition Center, PepsiCo, and Herbalife, among others.11

More troubling are ASN’s consistently industry-friendly positions on public health issues. The society’s purpose is to promote research and communication among members, not to speak for them about policies about which members might hold diverse opinions. ASN’s “big-tent” approach often appears to favor industry over public health, as several incidents demonstrate. Let’s take them in chronological order.

Sponsoring Smart Choices, 2009

In May 2009 I received an email from ASN’s program coordinator informing me that I had been nominated to join the board of directors of a new program, Smart Choices. This was a food-industry initiative in collaboration with leading nutritionists to put a stamp of approval on the front of packaged foods that met defined nutritional criteria. ASN was administering the program. My immediate reaction: Do not do this. Whatever this program did, it would make ASN appear to be endorsing products carrying the Smart Choices logo—a risky proposition. I wrote an open letter in the society’s newsletter saying so and declined the invitation.12

Although Smart Choices seemed to be aimed at helping the public identify healthier food options, it seemed clear that its underlying purpose was to induce nutritionists to endorse highly processed “junk” foods as healthy. The program also appeared to be an industry-designed effort to head off a plan, then under consideration by the FDA, to regulate front-of-package food labels. In his response to my open letter, Courtney explained that ASN had competed for oversight of the program and would be responsible for the program’s scientific integrity.13 I was not reassured.

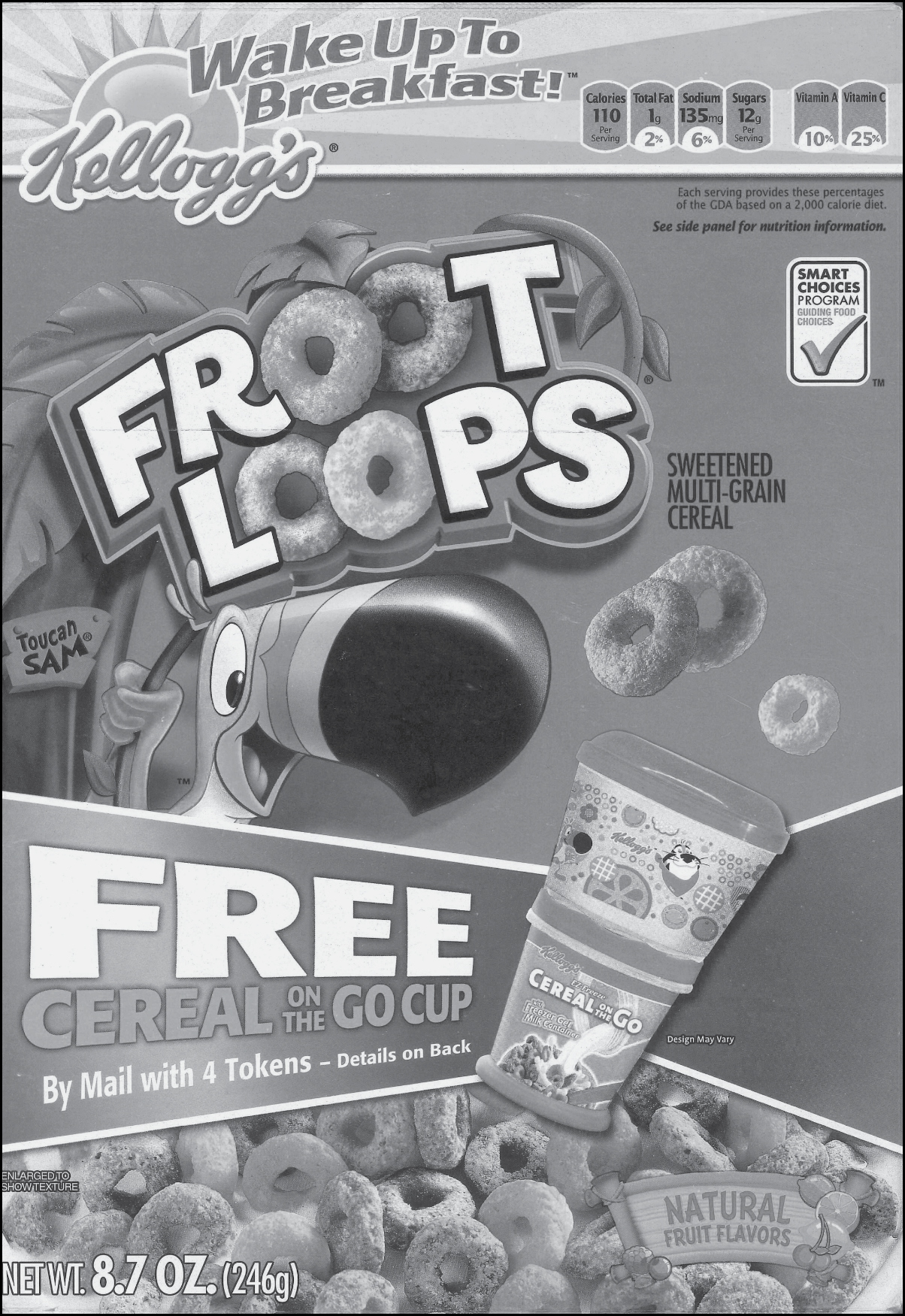

A few months later, William Neuman, a New York Times reporter newly assigned to cover the food business, asked to meet with me to discuss current issues in the nutrition world. When I mentioned Smart Choices, he suggested we head for the nearest grocery store. Because breakfast-cereal packages are redesigned frequently, we went straight to that aisle. There on the shelf was the first product labeled with the Smart Choices logo: Froot Loops—a kids’ cereal providing 44 percent of its calories from added sugars (Figure 9.1).

FIGURE 9.1. The Smart Choices check-mark logo appears near the upper-right-hand corner of this package of Froot Loops, indicating that the product meets the program’s nutritional standards. The Smart Choices board set the upper limit for added sugars at 25 percent of calories but made an exception for breakfast cereals. Added sugars in Froot Loops come to 44 percent of its calories.

Neuman’s article about this discovery appeared on the newspaper’s front page in September with the title “For your health, Froot Loops.” It reported that Michael Jacobson, CSPI’s executive director, had resigned from the Smart Choices panel in disgust: “It was paid for by industry and when industry put down its foot and said this is what we’re doing, that was it, end of story.… You could start out with sawdust, add calcium or vitamin A, and meet the criteria.” Neuman also quoted Eileen Kennedy, president of the Smart Choices board and dean of the nutrition school at Tufts University: “You have a choice between a doughnut and a cereal.… So Froot Loops is a better choice.”14 This quickly got translated to Froot Loops being “better than a doughnut,” or as the Economist put it, “It’s practically spinach.”15

The FDA and USDA jointly wrote to the Smart Choices program questioning whether its logo might encourage the public to select highly processed foods and refined grains instead of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Change.org filed a petition to end the program, distressed that nutrition experts were “happy to mislead the public about what constitutes a healthy/smart choice.” Connecticut representative Rosa DeLauro asked the FDA to investigate, and that state’s then attorney general, Richard Blumenthal, said he intended to investigate this “overly simplistic, inaccurate and ultimately misleading” program.16

By October, Smart Choices was history. The program announced postponement of all further activities pending the FDA’s decisions on front-of-package labeling.17 As Forbes explained, “[The] uproar over the program has conveyed a definitive message to industry: Don’t try to disguise a nutritional sin with a stamp of approval.”18 The ASN board sent a short letter to members explaining that the society fully supported the decision to postpone the program until the FDA made some decisions about front-of-package labels. The letter quotes ASN’s president at the time, James Hill (one of the founders, later, of the GEBN). He said that the society would “continue to provide nutrition science expertise within the dialogue on front-of-pack labeling in order to best serve the interests of the health of Americans.”19 I thought ASN should never have been involved in this enterprise in the first place and was lucky to have gotten out of it so easily. ASN’s leaders should have realized the reputational risk of involvement with a food-marketing initiative but apparently did not.

Promoting Processed Foods, 2012

In a collaborative effort with the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the Institute of Food Technologists (a professional society for food scientists), and the International Food Information Council (a food-industry group), ASN participated in writing a report promoting the importance of processed foods to nutritional health.20 Food scientists and food trade associations have a vested interest in promoting processed food products; nutrition organizations do not, but their collaboration lends credibility to the report’s conclusions.

Most foods are processed in one way or another, ranging from the minimal (washing, chopping) to the extensive (converting whole wheat to white flour). Processing often removes vitamins, minerals, and fiber while adding salt, sugar, and trans fats, making foods junkier. Independent nutrition groups generally recommend diets containing foods that are minimally processed.21 But ASN’s cosponsored report concluded “the processing level was a minor determinant of individual foods’ nutrient contribution to the diet and, therefore, should not be a primary factor when selecting a balanced diet.”

This report appeared in a supplement to ASN’s Journal of Nutrition with a statement that its first author and the supplement itself were supported by the sponsoring industry groups. That statement also explained, “Publication costs for this supplement were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This publication must therefore be hereby marked ‘advertisement’… solely to indicate this fact.” ASN’s participation in the report made it appear to support industry marketing objectives rather than those of public health nutrition.

Opposing “Added Sugars” on Food Labels, 2014

In 2014, the FDA proposed including information about “added sugars” on its revised Nutrition Facts labels. As is customary, the FDA asked for comments on this proposal.22 Consumer and public health groups supported putting “added sugars” on food labels, but the food industry opposed the FDA’s proposal. So did ASN. In supporting the food industry’s opposition, ASN explained that it had “concerns with FDA’s rationale for the inclusion of ‘added sugars’ on the food label.… Conclusions regarding added sugars remain elusive based on insufficient evidence regarding the effects of added sugars (beyond contribution of excess calories) on health outcomes.… ASN recommends careful consideration of the totality of the scientific evidence, as well as consideration of compliance and other technical issues.”23

ASN’s insistence that sugar policy be strictly “science-based” positioned the group as opposing a widely supported public health initiative. Eventually, the FDA not only ruled in favor of putting “added sugars” on the Nutrition Facts panel but also set a daily value of 10 percent of calories as an upper limit.24 ASN’s position on the science may have been technically correct, but it ignored the public health implications. In contrast to naturally occurring sugars in foods, added sugars are unnecessary. Nobody in or out of ASN thinks people should be eating more sugar. Encouraging people to eat less sugar is a reasonable public health objective, and ASN should have supported this measure.

Defending “Natural,” 2015

In response to petitions from consumer groups, the FDA requested public comment on the meaning of “natural” on food labels. Marketers of processed foods love the word because it is so frequently, but incorrectly, interpreted as meaning organic and healthy.25 The FDA’s current policy leaves much room for ambiguity: “From a food science perspective, it is difficult to define a food product that is ‘natural’ because the food has probably been processed and is no longer the product of the earth.… The agency has not objected to the use of the term if the food does not contain added color, artificial flavors, or synthetic substances.”26

Consumer groups want the FDA to clarify that this definition also excludes seemingly unnatural substances such as high-fructose corn syrup, foods that are genetically modified, or, perhaps, stevia’s “naturality.” They petitioned the FDA to come up with a more restrictive definition. But ASN argued for a more expansive definition that would allow the addition of synthetic vitamins. ASN correctly stated that many Americans interpret “natural” on processed foods to mean no pesticides, no artificial chemicals, and no GMOs, and that even more believe that it should mean these things. But the society argued for permitting the addition of synthetic vitamins because the diets of many Americans lack “important nutrients of public health concern”—a debatable contention, given the lack of evidence for widespread signs of nutrient deficiency in the general population. Marketing vitamin-fortified foods as “natural” opens the door to other “healthy” synthetic additives. Once again, ASN was supporting industry marketing interests against what some members of the society might prefer “natural” to mean.

Promoting Food Industry Sponsorship, 2016

In 2016, I accepted an invitation from ASN to serve as an adviser for its Early Career Nutrition Interest Group, which provides networking and mentoring for postdoctoral fellows and early-career faculty at annual meetings and also sponsors an award competition. ASN requires all groups running social and professional-development sessions at annual meetings to raise their own funding for hotel-room space, audiovisual support, and food. In the past, the Early Career group’s events had been sponsored by PepsiCo, Abbott Nutrition, and DuPont, for a total cost below $5,000. I thought ASN could easily cover these costs from annual and meeting dues, and said so, but was overruled.

One last example, this time from ASN’s use of social media. In September 2016, the online news magazine Slate published an article that asked, “So what if the sugar industry funds research? Science is science,” arguing that funding sources are irrelevant to the conduct or outcome of research.27 Whoever does social media for ASN supported this “science-based” position. ASN linked to the article on its Twitter feed with this comment: “Evaluating science on factors beyond data and methods impairs efforts to understand and advance nutrition science.”28 Industry funding is indeed a factor “beyond data and methods,” but it skews the science. While many members might agree with ASN’s position, others might not, and the organization has no mechanism for polling members on such questions.

ASN is a relatively small society, but it represents research faculty at universities and medical centers throughout the world. Although its actions establish ethical norms for the field, it places high value on the inclusiveness of its connections to food companies without regard to their ethical or reputational implications. ASN’s apparent support of food-industry objectives makes it seem to be favoring commercial interests over those of science or public health. It appointed the Trust Committee to address this problem. In August 2018 as this book went to press, the committee had submitted its findings and recommendations for publication but could not release them until completion of peer review. Whether the ASN board would approve the recommendations was as yet uncertain.

International Implications

ASN is an American society, but the issues that beset it are typical of nutrition societies throughout the world—US nutritionists just do not hear much about them. Critics have long objected to the ubiquitous presence of Big Food marketers at congresses of the International Union of Nutritional Sciences, but these take place only at four-year intervals.29 The last two were in Granada (2013) and Buenos Aires (2017) and did not get much press coverage in the United States.

But in 2017, the New York Times began to publish a series of investigative reports collectively titled “Planet Fat.” These articles describe in riveting detail the marketing methods used by international food companies to promote sales of highly processed food products in developing countries—Brazil, Ghana, Senegal, Colombia, Mexico, Malaysia, India, Chile—and, inadvertently, to promote the rapid rise in obesity and its health consequences in such countries.

The article about Malaysia is especially relevant to our discussion because it deals with the influence of food companies on the research and opinions of the country’s leading nutritionist, Tee E-Siong. Tee heads the Nutrition Society of Malaysia, a group funded by Nestlé and other food companies. He also is scientific director of ILSI in that region.30 The Times headline got right to the point: “In Asia’s fattest country, nutritionists take money from food giants.”31 In particular, Tee was senior author on a study sponsored by Nestlé and Cereal Partners Worldwide (a joint venture between Nestlé and General Mills). The study examined how Nestlé’s Milo (a sugar-sweetened, chocolate-flavored, vitamin-enriched malted milk drink) affected children who consumed it at breakfast. Unsurprisingly, the study found that children who drank Milo consumed more of the nutrients it contains. It also noted that Milo-consuming children were more active and had healthier weights than children who did not consume the drink—just the kinds of results Nestlé and Cereal Partners must have hoped for.32

Of the study’s twelve authors, four were employed by its sponsors. The paper’s disclosure statement noted that the funders “had no influence over the design or analysis of the research” but also noted that the authors who worked for the funders “critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content.” If so, how could there be no influence? A spokesperson for Nestlé told the Times that the company’s review of the manuscript was routine and aimed only “to ensure that the methodology was scientifically correct.”

In response to this article, an anonymous Malaysian scientist objected to suggestions that industry funding might influence the quality of Tee’s science. Instead, he wrote, Tee’s Milo investigation “is a valid and important scientific study that added an important contribution to the ongoing research about food intake and obesity.” Such comments induced David Ludwig, a Harvard specialist in childhood obesity, to post a detailed critique of the study’s design and methods—low participation rate, unmatched comparison groups, unvalidated methods, and statistical problems—concluding that the results were weak and susceptible to confounding.33

The Times further quoted Tee: “There are some people who say that we should not accept money for projects, for research studies.… I have two choices: Either I don’t do anything or I work with companies.” But other choices exist and are worth considering. The Times writers must have thought so, too. This research, they said, “exemplified a practice that began in the West and has moved, along with rising obesity rates, to developing countries: deep financial partnerships between the world’s largest food companies and nutrition scientists, policymakers and academic societies.” If professional nutrition societies are embedded in partnerships with food companies, they are, or can appear to be, front groups for the food industry, not independent sources of scientific advice about diet and health.