13

13

Managing Conflicts: Early Attempts

I BEGAN THE RESEARCH FOR THIS BOOK WITH A GREAT DEAL OF curiosity about when nutrition professionals first recognized the need to manage conflicted relationships and when and why the editors of nutrition journals first insisted that authors disclose funding sources and competing interests. I had the impression that concerns about conflicted interests were relatively recent. It never occurred to me that attempts to insulate researchers from undue industry influence began decades ago. Some of the history was readily available, but I had not known about it. Other aspects were only just coming to light through analysis of recently discovered historical documents. Because this history bears directly on today’s attempts to manage industry-induced conflicts of interest, it is worth recounting. For our purposes, it begins in the 1940s with The Nutrition Foundation, an organization created for the express purpose of pooling donations from food companies into a common research fund.

The Nutrition Foundation, 1942–1985

In the days before NIH funded basic research, money available for this purpose was limited. Scientists realized that research grants from food companies could compromise their independence and sought ways to accept industry funding while maintaining their integrity and reputations. The solution? The Nutrition Foundation. In 1942, Karl Compton, president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, agreed to head the board of trustees of this foundation, which had just been established through donations from fifteen leading food manufacturers, among them Campbell’s Soup, General Foods, Quaker Oats, and United Fruit. As he explained, the foundation would create a “strong” and “independent” program to support two kinds of research: basic nutrition research aimed at improving the food, diet, and health of the American public, and applied food-science research to help food companies with technical problems and product development.1

I put “strong” and “independent” in quotation marks because they have specific meanings in this context. In the foundation’s view, “strong” meant adequately funded. Its funding model was to persuade as many food companies as possible to donate $10,000 a year for five years. Later, it encouraged smaller companies to contribute as little as $500 a year. By 1947, fifty-four food, beverage, and supplement companies had committed to such contributions.

By “independent,” the foundation meant firmly separating the funding from the science. To achieve this, it created a scientific advisory committee to take full responsibility for reviewing applications and awarding grants—although decisions had to be approved by the foundation’s board of trustees. Because the trustees included food-industry representatives, this requirement should have set off alarm bells. It put the board in a position to control the research agenda, even though its approval process appeared to be pro forma.

We know this from a history of the foundation published in 1976 by Charles Glen King, who ran the scientific advisory committee for years.2 In his view, “the work of this committee and its rapport with the trustees were of such a quality that no grant recommendation to the board of trustees was denied or restricted in any way during my 21 years of experience as Director or President.” This statement should also raise questions about the independence of the advisory committee. If members wanted to remain on it, and if the committee wanted companies to continue donating to the foundation, everyone would need to meet the trustees’ and donors’ spoken or unspoken expectations. Gifts, as we have seen, create obligations.

Researchers who obtained grants from the foundation could use the money to support graduate students, postdoctoral scholars, or staff and to buy equipment and supplies. The foundation awarded its first grants in 1942: thirty-six awards totaling $123,890. For example, William Rose at the University of Illinois received $3,600; Stanford University’s George Beadle got $6,000; Cornell University’s Vincent du Vigneaud was awarded $3,800. Small as these grants may seem, they contributed to some highly distinguished careers. Rose went on to win a National Medal of Science, and Beadle and du Vigneaud eventually won Nobel Prizes. The foundation soon increased the amounts; it gave out nearly $2 million to investigators at sixty-two institutions in 1943.3

Despite King’s protestations of independence, some nutrition scientists must have had doubts. King quotes an unnamed member of a nutrition society as saying, “Of course you will have to scratch the back of your member companies occasionally and do little favors according to their interest!” But King insisted the foundation was not run that way. The foundation’s charter specified that “no founder or sustaining member of The Nutrition Foundation, Inc., shall refer to his membership in this corporation in his advertisement of his products; or make any other commercial reference to said membership.” King’s history quotes a speech given to the foundation’s trustees in 1972 by its then president, William Darby: “The Nutrition Foundation must provide leadership of integrity. It will not become a lobbying agency and must remain scientifically detached in debates affecting any particular segment of the food industry.”

Nevertheless, some skepticism is in order. Yes, the grant recipients got essential funding, for which they thanked the foundation in their published papers. But surely the food-company donors expected some return on their investment? The foundation’s leaders evidently thought so. They established an industry advisory committee that kept member companies apprised of the foundation’s work, gave them early information about study results, and provided informal access to leading nutrition scientists. There were, of course, tax advantages. If I am dubious about the claims of independence, it is because the foundation’s funding model required repeated commitments from participating companies and, therefore, created ongoing pressures to please.

Over the years, the foundation expanded its activities beyond giving out research grants. From the start, it published its own journal, Nutrition Reviews (which still exists), but it gradually took on additional missions. It helped establish similar foundations in other countries, gave awards, published books, funded conferences, and entered into partnerships with other nutrition organizations. Its financial needs grew accordingly.

Pressures to please may well explain why foundation executives sounded so much like representatives of the food industry whenever they made public statements about nutrition and health. Reporters came to view foundation officials as spokesmen for the food industry. In 1962, for example, King told a reporter that Rachel Carson’s just-published book Silent Spring seemed to be “bordering on hysteria.” The reporter identified King as the head of a “research-sponsoring organization largely supported by the food industry.”4 In 1967, Horace L. Sipple, who was then the foundation’s executive director, suggested that mothers could fix their families “hot dogs and malted milks or even pizza for breakfast. ‘It’s better than nothing at all,’ he said” (a statement reminiscent of the assertion, decades later, that Froot Loops is better than a doughnut).5 In 1974, the foundation’s president, William Darby, denounced academics concerned about the hazards of agricultural chemicals for their McCarthyite attack on the pesticide industry,6 and in 1982 he said of the 1980 dietary guidelines, “I don’t think we should look at food-stuffs as being dangerous things.… If we cut down on animal products such as lean red meats we remove one of our best sources of protein, B vitamins and iron” (a statement that may be scientifically correct but ignores the public health implications of processed meat consumption).7

By the time Darby made that statement, nutrition science was changing. Government research funding, which had increased rapidly after the end of World War II, had begun to focus on cancer, heart disease, and other chronic conditions rather than vitamins and minerals. Food companies were closing their basic-research units and shifting resources to marketing. When mergers and acquisitions consolidated the food industry, fewer companies were available to contribute to the foundation’s work, and its financial situation deteriorated. In 1985, the foundation solved its financial problems by merging into ILSI, thereby confirming its status as a food-industry front group.8 The moral: it takes more than pooling funds from food companies to maintain research independence. This moral is also evident from another example: Fred Stare’s research fund at Harvard.

The Fred Stare Era at Harvard, 1942–1976

Stare founded the Harvard Department of Nutrition in 1942, chaired it until 1976, and remained involved with it until the 1990s (he died in 2002). In part because he so actively solicited contributions from the food industry and others, Stare also came to be viewed as a front man for the food industry rather than as an independent scientist.

His method for assuring “independence” was to require that all donations be entirely unrestricted. He pooled the contributions into a common Fund for Research and Teaching and, later, into endowment funds. In his autobiography, Stare explained, “It would have been easy to get generous support from the food industry if we would have conducted research on specific food products and hopefully improved them. But we were not a Department of Food Technology or Food Science. My major effort was to convince these leaders of the food industry that they should be willing to provide unrestricted funds for support of basic research… in addition to support of food technology which might result in improved products.”9

He was persuasive—this was Harvard, after all—and the fund grew. By the mid-1950s Stare had already obtained more than forty grants from private sources. Eventually, his sponsors included drug companies, supermarkets, unions, meat companies, sugar companies, fast-food companies, and every imaginable food or beverage trade association, as well as major food, agriculture, and even tobacco companies. From 1942 to 1986, he collected nearly $21 million in unrestricted funds. By 1990, the endowment alone came to more than $9 million and produced an income of $800,000 a year. Stare boasted that these funds accounted for only a fraction of the department’s outside support: “In our most productive years (1955–76), government funds averaged 80 percent of our total support and unrestricted private funds approximately 20 percent.”10 Stare personally contributed to that 20 percent: “Honoraria, book royalties, and fees from my syndicated columns have all gone to a fund that provides unrestricted support.” He explained, “By giving personally to the financial support of the Department, it has been easier to get support from other private sources.”

But Stare ran into precisely the same difficulty faced by the Nutrition Foundation: the need to please donors to get ongoing support. For this reason, or perhaps because his personal beliefs coincided with those of his donors, he was widely recognized as a nutrition scientist working on behalf of the food industry. His public statements consistently defended the American diet against suggestions that it might increase the risk of heart or other chronic disease. He, like officials of the Nutrition Foundation, could be counted on to state the industry position on matters of diet and health and to assure reporters and Congress that no scientific justification existed for advice to avoid food additives or eat less sugar.11

We now know much more about the depth of Stare’s food-industry ties from documents that came to light in 2016 when Cristin Kearns and colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco published an analysis of internal documents of the Sugar Research Foundation (SRF), the forerunner of today’s Sugar Association. The documents included letters between the SRF and Mark Hegsted, a faculty member in Stare’s Harvard department, about the SRF’s sponsorship of a research review on the effects of dietary carbohydrates and fats on cardiovascular disease. The review, written by Stare, Hegsted, and another colleague, appeared in two parts in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1967. The letters show that the SRF not only commissioned and paid for the review but also pressured the Harvard authors to exonerate sugar as a factor in heart disease, then and now the leading cause of death among Americans. Other documents from the mid-1960s demonstrate that the SRF withheld funding from studies suggesting that sugar might be harmful.12

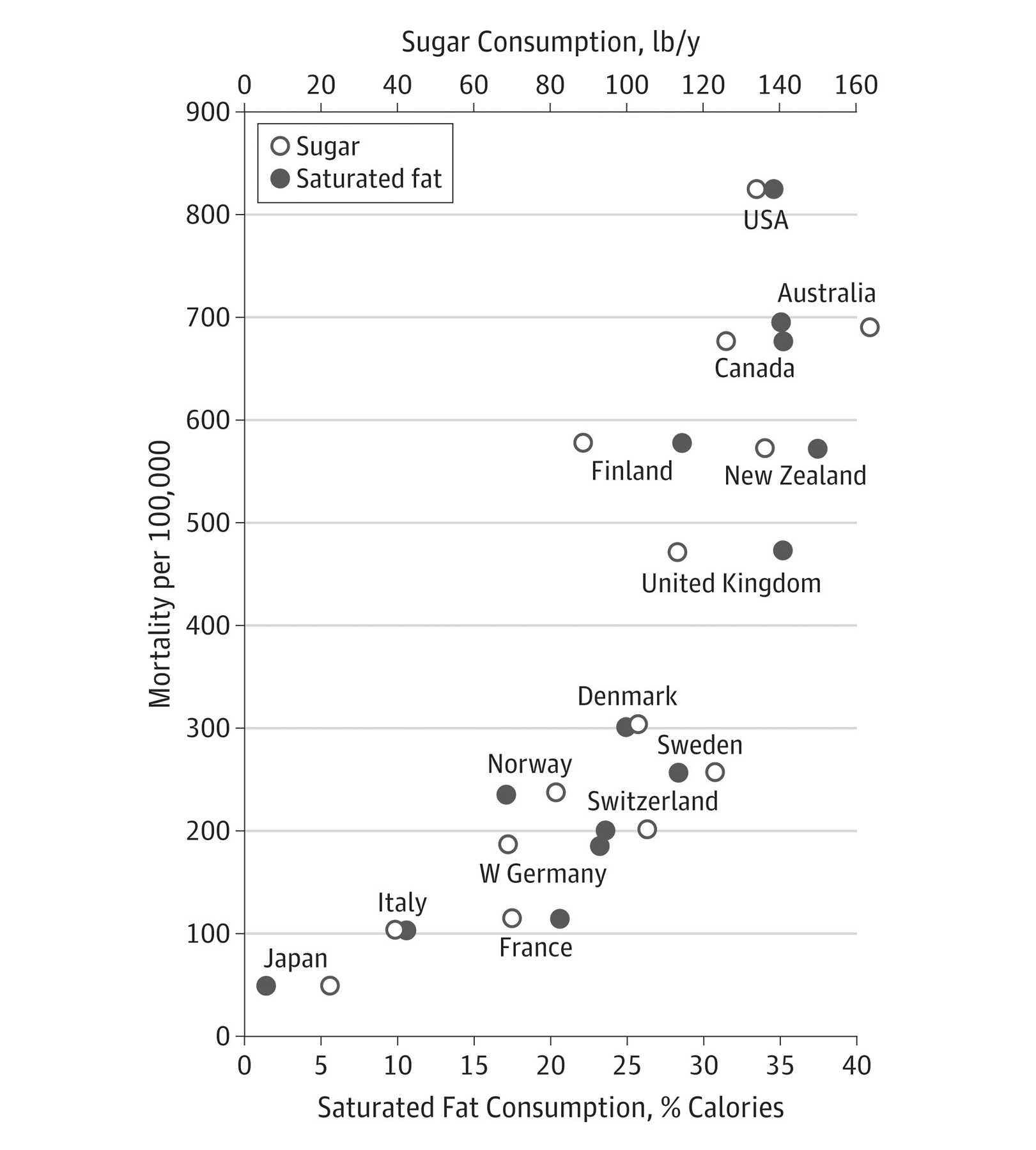

I wrote the editorial that accompanied the paper about the Harvard scientists’ work; in it, I explained that studies at the time suggested that diets high either in sugar or saturated fat were associated with a higher risk of heart disease.13 But the SRF wanted scientists to ignore sugar and focus on fats. The Harvard investigators had previously published research implicating both sugars and saturated fat as risk factors for heart disease, as their two-part review makes clear. Figure 13.1, which I adapted from their study, compares sugar and saturated fat “consumption” (in reality, amounts in the food supply—a proxy for consumption) to the risk of death in fourteen countries. In those countries, sugar and fat availability are indistinguishably correlated with mortality—an association that suggests but does not prove causation. To strengthen the case against saturated fat, the Harvard investigators appear to have cherry-picked the data by giving far greater credence in their conclusions to studies implicating saturated fat than they did to those implicating sugars.

These authors are all deceased and cannot be asked what they were thinking at the time. Hegsted’s role is especially puzzling. He was well-known for developing the “Hegsted equation” for predicting the rise in blood cholesterol that occurs in response to consumption of specified amounts of saturated fat and dietary cholesterol.14 But he was also revered in the public health community for promoting healthful diets in general, including diets reduced in sugar. As he testified in 1977, “The diet of the American people has become increasingly rich—rich in meat, other sources of saturated fat and cholesterol, and in sugar.… What are the risks associated with eating less meat, less fat, less saturated fat, less cholesterol, less sugar, less salt, and more fruits, vegetables, unsaturated fat and cereal products—especially whole grain cereals. There are none that can be identified and important benefits can be expected.”15

FIGURE 13.1. The close correlation between sugar and saturated fat “consumption” (availability in the food supply) and overall mortality in fourteen countries. Correlation does not necessarily imply causation; a high intake of either sugars or saturated fats also correlates with other dietary and lifestyle factors that can affect mortality. Reproduced with permission from JAMA Intern Med. 2016, 176(11):1685–1686, ©2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Nevertheless, the 1967 reviews dismissed the need to reduce sugar consumption. How important were these papers? It is hard to say. They were not cited among the more than nine hundred references to a book-length report on sugars and health issued by the FDA in 1986 (which concluded that sugars caused tooth decay but not much else). A more recent analysis of the 1960s debates about sugar and fat, which refers to my editorial, ignores the cherry-picking and instead suggests that the focus on sugar-industry funding constitutes a “conspiratorial narrative” obscuring a more complicated history of uncertainty in nutrition science.16

Since 1980, US dietary guidelines have consistently called for eating less sugar, although mainly to reduce “empty” (nutrient-free) calories or to prevent tooth decay. Only in 2015 did the guidelines finally advise eating less sugar as part of an eating pattern to reduce risks for chronic disease, the same year that WHO deemed sugar a major risk factor for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and other chronic conditions. With respect to saturated fat and sugar, overall dietary advice remains much the same as it has been since 1980, but the reasons for the advice about sugar have expanded. This expansion may be why the balance of media concern about fat and sugars has shifted. Time magazine says scientists were wrong about fat and “butter is back,” and journalists write books arguing that sugar causes chronic diseases ranging from obesity and type 2 diabetes to gout and dementia.17

Food companies have responded to these trends by trying to remove as much sugar as they can from their products, an example of “nutritionism” in action. This term was coined by the Australian sociologist Gyorgyi Scrinis and popularized by Michael Pollan to describe the reductive use of single nutrients or food components as proxies for dietary patterns that affect disease risk. Sugars and saturated fat are both markers of Western dietary patterns associated with overeating, overweight, obesity, and related chronic diseases. Food companies benefit when dietary advice focuses on single nutrients or foods—it makes marketing easier.18

The Nutrition Foundation and Harvard examples show that pooling industry funds is insufficient to avoid conflicts. But these examples illustrate one additional point: the need for disclosure. The 1967 reviews acknowledged support from several government and private sources, among them the Nutrition Foundation and the Harvard Fund, both known—at least to insiders—as funded by industry. But the authors did not mention funding by the SRF. At the time, this omission violated no rules; medical journals did not begin to require disclosures until the 1980s.

Nutrition Journals: Disclosure Policies

From the start, nutrition investigators voluntarily disclosed who paid for their studies. In its first two years of publication, 1928 and 1929, the Journal of Nutrition included forty-eight research reports and commentaries, most of them dealing with the effects of vitamins or minerals on rats. Of these, eleven articles acknowledged external funding, mostly from universities or the USDA, but four acknowledged funding from food or drug companies: Northwestern Yeast, Mead Johnson, Eli Lilly, the National Livestock and Meat Board, and General Foods.

For decades, disclosure of funding sources in journal articles remained voluntary. In 1960, a new editor of the Journal of Nutrition, Cornell nutrition professor Richard Barnes, added this note to its guidelines for authors: “Financial support should be listed as a footnote to the title. Credit for materials should be listed as a footnote to the text.”19 But “should” referred to where the information should be placed, not to the need to include it. In the late 1960s, when I published my dissertation research, acknowledging sources of funding was expected as a courtesy to the funder or was required by federal granting agencies as a condition for support. My papers included footnotes saying, “This work was supported in part by Research Grant CA 10641 from the National Cancer Institute, United States Public Health Service.”20

Only in 1990 did the Journal of Nutrition introduce new instructions. Authors would henceforth need to provide “a statement of financial or other relationships that might cause conflict of interest.”21 The journal introduced this requirement without explanation. I tracked down several editors listed on the 1990 masthead to ask if they could recall what had prompted the new disclosure requirement.

Robert Cousins, now eminent scholar and director of the Center for Nutritional Sciences at the University of Florida, told me that he and Alfred Merrill had been invited to serve as associate editors by the journal’s editor, Willard Visek: “Willard was an MD and attended meetings of medical journal editors.… The conflict requirement may have developed from that exposure also. He may also have seen that some authors had ties to industries that could be conflicts.”22 Cousins was referring to meetings of the Council of Biology Editors, now the Council of Science Editors, an organization of editors of about eight hundred science journals.23 Among these journals was the New England Journal of Medicine, which in 1984 became the first to require authors to disclose their ties to drug companies.

The other associate editor, Alfred Merrill, now the Smithgall Institute Professor of Molecular Cell Biology at the Georgia Institute of Technology, recalled that the journal had seen many cases in which papers came from authors who had potential conflicts of interest because of either the funding source or their own affiliations. “Our policy,” he said, “was to evaluate the science at face value, and if solid, publish the papers but ensure that issues that were of potential concern (e.g., funding source) were clearly stated. Statement of the funding source seemed important since there were a lot of studies funded by the National Dairy Council and other groups with industry connections.” Visek, he added, “was very emphatic that the guiding principle for the journal should be the scientific rigor and not whether what was found would be out of vogue.”24 Merrill mentioned an example to illustrate that point: a study sponsored by the egg industry reporting that cholesterol from any source, not just eggs, raised blood cholesterol levels.

Although Merrill did not give me a specific reference for that study, I could see why he thought of an example like that. In 1993, he had written an editorial about another study sponsored by the egg industry. Egg sales had been declining for forty years by then, and the egg industry was actively sponsoring research to counter advice to reduce cholesterol intake. Merrill’s editorial referred to a 1992 study by J. L. Garwin and colleagues of eggs modified to be lower in saturated fat. Garwin’s group measured the effects of eating the modified eggs on the blood cholesterol levels of human volunteers. The study, sponsored by the developer of the modified eggs, concluded that people on cholesterol-lowering diets could consume a dozen of these eggs a week with no noticeable effect (not surprising, given that their overall diets counteracted any effect of eggs on blood cholesterol).25

Readers wrote letters to the editor objecting to the study’s methods and conclusions. One pointed out, “The ‘modified’ eggs command a premium price in the marketplace that we think is unwarranted, and the fact that this article was published in THE JOURNAL OF NUTRITION could be taken to indicate that the nutrition community accepts the claims of the ‘modified’ egg producers.”26

In his editorial, Merrill noted two separate concerns about the egg study: “The first regards the criteria for academic speculation about the possible explanations for experimental observations; the other deals with the possible commercial impact of such speculation.… Because various interpretations can be given to statements in any manuscript, it will remain important for authors to identify possible conflicts of interest.” He noted that Garwin’s article disclosed the funding source but added, “As these issues become more complex, it may be appropriate for THE JOURNAL OF NUTRITION to encourage authors (and reviewers) to identify all sources of possible conflict of interest.”27 But the journal had required precisely this information since 1990, suggesting some concern about whether authors were fully complying. I mention these details because Merrill’s 1993 editorial is the only discussion of the need for disclosure I can find in any American nutrition journal prior to the 2000s. In contrast, writers in medical journals had been arguing about disclosure issues for many years.

Authors publishing in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition also voluntarily disclosed funding beginning with its inaugural issue in 1952. That first issue contained three reports about the effects of vitamins that acknowledged sponsorship by one or more supplement companies—Merck, Wm. S. Merrill, Chas. Pfizer, Hoffman–La Roche, and Wyeth. Perhaps because of widespread voluntary compliance, this journal’s instructions to authors did not mention disclosure until 1981, when it advised acknowledging “the sources of support in the form of grants, equipment, drugs, or all of these.” Only in 2002 did the journal add, “Each author is required… to disclose any financial or personal relationships with the company or organization sponsoring the research,” and it also specified that “such relationships may include employment, sharing in a patent, serving on an advisory board or speakers’ panel, or owning shares in the company.”28 I asked D’Ann Finley at the University of California, Davis, a long-serving member of the journal’s editorial staff, if she could tell me why the editors had added the statement. She too suggested that editors must have heard these issues discussed at meetings of the Council of Biology Editors and thought they should follow its guidelines.29

The Journal of the American Dietetic Association (since 2012, the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics) published its first issue in 1925 and introduced requirements for funding disclosure in 1992. Instructions that year said, “Authors should also disclose financial support or gifts of equipment or supplies in an acknowledgment” and should make sure that “any financial or other relationships that might cause a conflict of interest have been brought to the attention of the editor.” It introduced an ethics statement the next year and, in 1995, a separate conflicts-of-interest section: “Authors must inform the Editor in writing of any financial arrangements, organizational affiliations, or other relationships that may constitute a conflict of interest.” Beginning in 2001, the editors’ calls for this information became increasingly strident: the instructions that year said, “Authors must inform…”; those in 2002 said “authors must inform….”30

To summarize: two kinds of disclosure statements are at issue here—revealing funding (who paid for the study itself, in part or in total) and revealing competing interests (authors’ financial ties to relevant companies). Historically, authors acknowledged funding sources voluntarily. Their failure to do so did not become an issue until food companies began to pay for studies more expressly designed to meet marketing objectives. The journals I have just mentioned began to require disclosure in 1990, 1992, and 2002, respectively. The Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior required disclosure of study funders even earlier—in 1989—but to this day does not require authors to disclose their personal financial conflicts.

This history suggests that some journal editors viewed disclosure as essential; others not so much. But nutrition journals generally lagged behind medical journals in demanding disclosures by authors. This brings us to the present. Disclosure matters but is only the first step in management of conflicts of interest. It is now time to look at what is being done—and what ought to be done—to deal with the conflicts induced by food-industry funding.