6. In the Field: What Do I Photograph?

“Landscape photography is the supreme test of the photographer—and often the supreme disappointment.” —Ansel Adams

Rule Number One: Forget All Rules

Starting with that non-sequitur, let me ask a question: Why are you a nature photographer? What is there about nature that makes you passionate about photographing it? Birds? Trees and forests? Flowers and plants? Insects? Reptiles and amphibians? Animals in the wild? Rivers? Mountains? Swamps? Deserts? Seashores? Your answer, very likely, is all of the above.

My reason for asking is to get you thinking about your whole relationship with nature. Chances are, if you live in an urban environment you find your visits to wild country to be refreshing, invigorating, and inspiring. You visit nature with the idea of capturing, in photographs, what it is that brings out in you good feelings about wildness—the uplifting of spirits, the beauty.

What does this have to do with conservation? Everything. Your subject matter becomes that which really matters. You want to make it matter to others as well because you want to rally support for your cause.

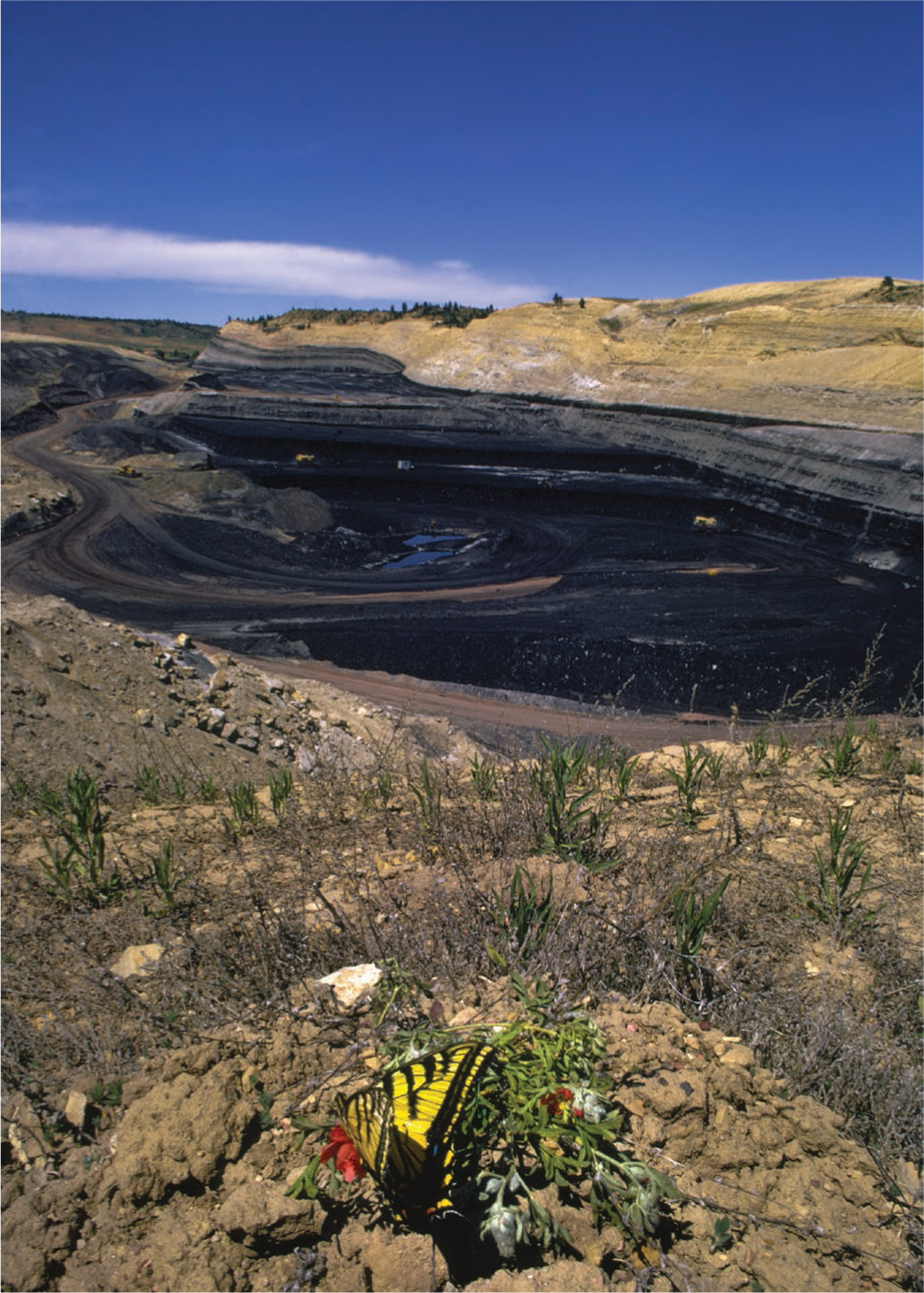

As a nature photographer, you can capture the delicate beauty of a butterfly on a flower. As a conservation photographer, you may also want to photograph that butterfly on the flower with a bulldozer in the background. This points to the fact that you need to become a documentary photographer as well as a nature photographer. This will entail photographing certain subjects and scenes that had never appealed to you before. But storytelling is what documentary photography is all about. Think story.

Shots like this show your audience the quiet and subtle beauty of nature and the delicate nature of ecosystems.

A similar butterfly in a totally different scene helps depict serious threats to ecosystems. This was serendipitous. I was documenting the massive impact of strip mines in Wyoming and Montana and spotted this butterfly on the edge of one of these open pit mines. With a 20mm ultra wide angle lens I could relate the delicate insect to the encroaching mine.

The butterfly flitted even closer to the edge of the mine and I backed off a little and used a100mm focal length this time to make the mine loom large in the background.

Cryptogamic (crypotbiotic) soil in Canyonlands National Park is easily damaged by grazing (left) and especially off-road vehicles (above) and takes decades or longer to recover.

A recent photo on a Colorado interstate highway of weekend traffic returning home. Part of the story.

Research is vital before embarking on a major documentation project. In the past, this research took lots of time but today, using the Internet and e-mail, you can quickly gather a lot of information about a region and its ecosystems. Be thorough in your research and be sure to contact researchers in the region who can give advice and important information. Also check with government agencies in the region and with universities that may have biological and ecological studies going on. This information can guide you in selecting what to photograph and makes your photographs much more important and relevant.

Not all of your documentation may be dedicated to giving protection to unprotected places. Often, there are detrimental things happening even in our protected areas, and it’s vital to record them and bring public attention to these threats. In addition, photographs of certain activities and damages can be of legal importance in alleviating them.

For example, human impact in our national parks and other reserves has damaged some delicate ecosystems. In the high desert of Utah (in the Canyonlands and Arches National Parks among others), there is something called cryptogamic or cryptobiotic soil—a crust comprised of microscopic organisms that perform important ecological roles, including carbon and nitrogen fixation, retention of water for nutrients, and soil stabilization. Footprints, grazing, and especially off-road vehicles can cause serious damage to this soil—damage that may take a century or more to recover. Again, think story.

We have impact in other ways, too. The number of people seeking enjoyment on our public lands can be overwhelming at times. The traffic photo on the facing page was made on a Colorado highway when people were returning home from spending a weekend in the region’s mountains, forests, lakes, and streams.

Capture the Essence of the Place

As a conservation photographer you must ask yourself, “How do I portray my concerns?” If you are involved in a project that hopes to protect a certain place, it’s obvious you must capture the essence of that place—the beauty, the solitude, the grandeur, and the details. The documentation should have a variety of images—bird and animal life, forest, flowers and plants, and water in all its forms that nourish the life here. In addition, you should show people enjoying it—hiking, picnicking, photographing it, etc. It is particularly effective to show young people enjoying nature. That’s part of the story.

Careful Observation. When working in the field, often I find it necessary to sit quietly and absorb my surroundings. If I am with companions, I like to wander off by myself because simply interacting with friends is a distraction. I need to concentrate. At these times, I may put the cameras aside for a while and just look and listen and breathe in the aromas. For me, it is a Zen-like state in which I try to open my senses to everything happening around me.

I don’t mean to get too esoteric here, but there is an importance to simply taking it all in. In time, something will catch my attention—the play of light on leaves, or sparkles of water rippling in a stream, or maybe the way a flower sways to a breeze, or the long shadows cast by stately trees. When I have begun to recognize the interconnectedness of the elements in a given place, I pick up the camera and try to convey it in one or more images. I don’t always succeed on the first try. Sometimes I don’t succeed at all. But what often happens is that I find myself looking for entirely different ways of portraying the familiar. I’m bored with the old ways I have made images. I want someone to look at this photograph and think, “Yes—that’s the way I feel about it, too.” Ansel Adams was once quoted as saying, “I can look at a fine photograph and sometimes I can hear music.” Shoot for the rhapsody, listen for the symphony.

In documenting unspoiled places, it’s effective to show how children interact with nature. Who doesn’t daydream by a stream?

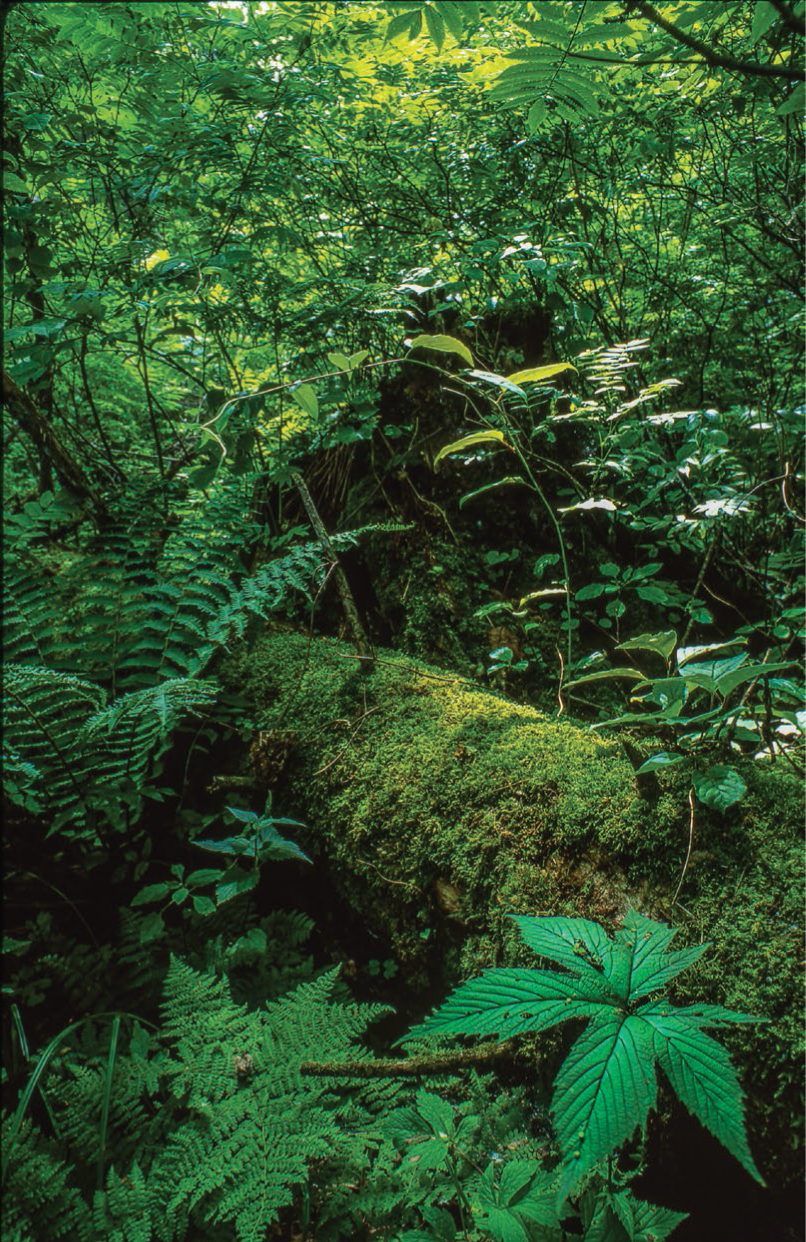

The undergrowth was so thick that it was difficult to convey the forest’s lushness and biodiversity. I did manage to find this old Manchurian oak tree, embraced by a younger one.

I don’t know what it is, but sometimes images just leap out at you, like those image-search puzzles (“How many squirrels, horses, lions, etc., can you find in this picture?”) you sometimes see in magazines or newspapers. You stare and stare—and all of a sudden what was once a chaotic jumble of shapes and lines resolves into something recognizable.

This happened to me in the dense forest of the Bikin River Valley in the Siberian Far East (above left), where I was documenting the threat of clear-cut logging to the habitat of some of the last remaining Siberian tigers (estimates vary, but some put it at only 300 left in the wild). This is not typical Siberian taiga (boreal forest) with its ramrod straight pines, larches, and stark white birches. This region is Asian temperate forest, more reminiscent of a jungle. It looks like a rainforest—lianas wrapped in a strangle-hold around giant birches; dense, feathery ferns standing hip deep in spongy soil; plus brambles that reach out and snare sleeves, collars, and camera straps, and leave itchy little scratches on bare skin.

Lens Selection. I was hiking through this forest (facing page), following what was supposed to be a trail—cursing at the dense foliage for hooking onto the tripod slung over my shoulder and glancing back frequently (this is Siberian tiger domain; there aren’t many left, but I’d seen a huge tiger track the day before). I was sweating in the humidity and swatting pesky little flies, when suddenly I saw it. Because of the density of the foliage I had almost given up on broader forest shots (yeah, yeah, I know—can’t see the forest for the trees). But there it was: a graceful old Manchurian oak tree, embraced lovingly by another, younger tree. I felt like a voyeur. (How many centuries has this hanky panky been going on?)

I would have preferred to back off and use a telephoto (maybe a 200mm) to isolate the subjects and drop out some of the background with shallow depth of field—but I couldn’t because of all the branches in the way. So I mounted my camera on a tripod and composed the picture using my 35–70mm zoom at 35mm. As it turned out, this lens nicely captured what I saw and felt. And, in a short distance, I began to find other good photo possibilities as the forest opened up to a floor covered with ferns and grasses.

I made this photo from a narrow trail winding through the rainforest of the Tambopata-Candamo Reserve in the Peruvian Amazon Basin. I used a 20mm focal length so that I could get a vertically wide angle of view to show this buttress root of a tree and some associated ground foliage. (Also, I couldn’t back up off the trail because of thick foliage.) Tropical rainforests have poor soils and the nutrients remain largely near the surfaces. Instead of putting down deep roots that would bypass the nutrients, trees here mostly have buttresses that spread along the surface area to gather these nutrients. They also help support the tree in high winds. Part of the story.

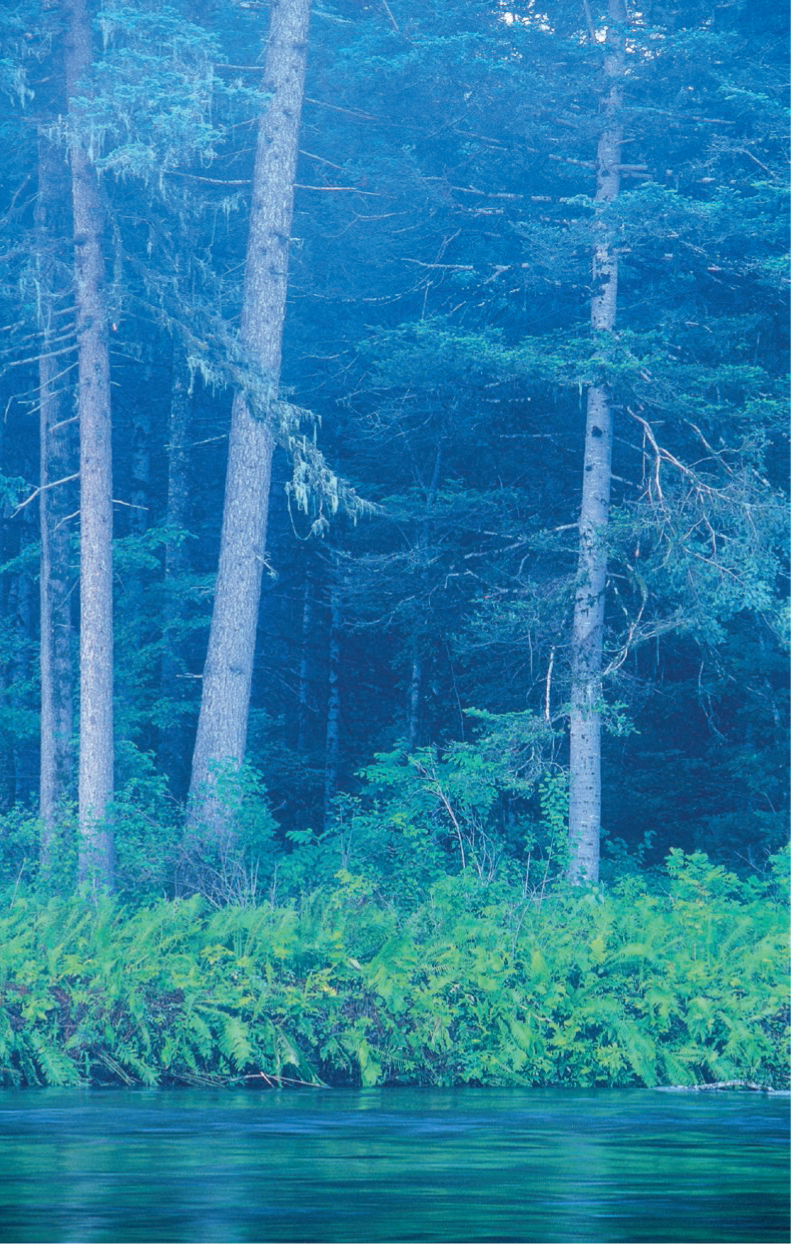

A view of the dense forest in the Russian Far East, looking into the forest from a natural edge—in this case, the Bikin River. Mist over the river softened and darkened the view, adding a sense of mystery. This is prime habitat for the remaining Siberian tigers.

Moving inside that Bikin forest to photograph presented difficulties because of the chaos of vegetation. I found one view of a fallen, decaying tree trunk with a wild ginseng plant in the foreground (lower right). The plant gave a center of interest amidst the jumble of vegetation. Overall, this image gives a strong sense of the biodiversity of this ecosystem. I shot with a 20mm ultra-wide lens to give some depth to the picture by including enough background in the view.

Another natural forest edge—this time along a wide stream in Borneo’s Danum Valley. The photo gives a good sense of the height and variety of trees. I shot with a 70–210mm zoom lens at about 100mm. I tightened the composition by zooming in slightly. The compositional elements are the lines of the trees along with the patterns formed by the foliage, trailing off into the misty hillside above.

For forest photography, wide and ultra-wide lenses (10mm up to 35mm) can be useful tools. Why? Forest ecosystems—especially rainforests—tend to be confining and chaotic. Sometimes, as I noted above, it’s desirable to back off and get an overall view. In the confines of a dense forest, however, that’s not always possible. Even though you may be on a well-maintained trail, it’s hard to back up and get a shot looking at or into the forest. A wider angle of view becomes necessary to get that interface shot. In addition, I always like to have a lower perspective to show parts of the forest floor. It helps to convey the biodiversity of such places.

Natural Openings. A technique for portraying an overall sense of the forest is to find a natural opening or forest edge and to photograph that edge straight on. I emphasize the word natural because, for example, if you use the open forest edge along a road or highway, it probably will include certain unnatural vegetation that sprang up in association with the disturbance in building the road. A natural edge containing normal vegetation would be along a river, stream, pond, or natural meadow in the forest interior.

Lighting and HDR. Sunlight is a killer of forest photographs because of the immense contrast range. You get dappled lighting, with bright white spots of light and black holes for shadows. When I used to shoot film, it was impossible to blend all that into a single picture; films just weren’t capable of handling those extremes in a single exposure. The sensors in digital cameras today are better in that regard, but still it’s difficult. Some people employ the technique of HDR (high dynamic range) imaging by making several bracketed exposures with the camera on a tripod, then blending them in Photoshop to capture both the hot spots and the dim shadows. However, a great many HDR photos do not look real. Many overcorrect for the great range of brightness and darkness and create something almost surreal. I prefer to wait for better lighting conditions.

Rainforests. Fortunately, many rainforests I visit tend to be overcast and rainy (they don’t call it a rainforest for nothing). That softer overcast lighting is perfect because it reduces the extreme contrast and brings out the colors in the vegetation—especially after a rainfall. When the rain stops, the vegetation gleams. Things get a little soggy, but they dry out later (camera gear is stowed in waterproof bags and covers). When photographing the wet forest, I look for images that would evoke that smell, that feeling of wetness, and that boundless diversity of life springing from it.

However, there is still the vegetative density to deal with. In some areas of the Amazon Basin where I’ve documented the rainforest, I found areas where I can get above the ground and even at the top level of the forest canopy. These have been at eco-lodges that have constructed platforms or towers to give views from above ground—perfect for giving a different perspective on rainforests.

Gleaming foliage after a rainstorm in the Venezuelan rainforest. Remember how I said to create order from chaos? Well, forget what I said. Sometimes, the chaos of vegetation conveys that sense of variety and biological diversity. I composed this picture to use that tree trunk as a focal point, surrounded by the anarchy of plants.

A documentation of the renewal of life from the decay on the forest floor in the Peruvian rainforest. You cannot photograph smells, but to me this photo evokes that earthy odor of decay and wet soils. I shot it with a 100mm macro lens.

The view of the Ecuadorian rainforest from part way up a viewing platform built around a large kapok tree. From a composition standpoint, the photo works because there is a subtle rhythm in the lines and the patterns of foliage. The lens was a 15mm ultra wide angle. I was careful not to point it up or down too much because that wide an angle of view gives a distorted perspective of vertical lines.

Green scarab beetles in the Peruvian rainforest in the Amazon Basin. A territorial dispute or mating ritual? Either way, the brilliant color stands out against the decaying leaves on the forest floor. I shot this with a 100mm macro lens.

I think we too often look for familiar things to photograph. It’s like the people you travel with occasionally who look at some magnificent landscape and say, “Gee, this looks just like _______.” The things that remind us of another place make us feel comfortable, I guess. But it’s a trap photographically. I look for what’s different about a place.

I haven’t forgotten about photographing that most important part of rainforests: rain. It’s not easy, but it can be done without drowning your equipment or using waterproof cameras. In the illustrations on the facing page, I did use a shelter in the Ecuadorian rainforest at the edge of the Rio Napo River. The successful technique is to use a focal length long enough to keep the background slightly out of focus to maintain a visual sense of place.

So, you’ve done a good job of capturing the essence of a place. Now you should also consider what will happen if that place is not protected. What are the threats? Logging? Land development? Mining? A dam? You should seek out other places that have fallen victim to such things and show the consequences. In this regard, Susan Sontag may be wrong. Sometimes we can discover, or re-discover, ugliness through photographs. And certainly side-by-side comparisons between the spoiled and unspoiled have huge impact.

In this downpour in the Ecuador rainforest I used a 70–210mm zoom at 210mm to shoot from across the river. The focus was on the foliage on the river’s edge. It doesn’t capture the feeling of the downpour aside from raindrops splattering on the water’s surface.

Switching to manual focus, I set the focus for a distance somewhere in the middle of the river and used a slow shutter speed (about 1/15 second) with the lens at its maximum aperture for a minimal depth of field. This allowed me to capture streaks of rain. You could add what would appear to be rain streaks using some Photoshop trickery—but that’s cheating.

If you’ve trained yourself to seek out and capture the beauty of nature, you may initially find it difficult to capture the destruction and devastation of it. There is a dichotomy. However, we can use some of the same principles of composition, lighting, and perspective to convey the starkness of destruction. It is not our task to create beauty out of ugliness; rather, we want to emphasize the ugliness created by destruction.

Dams. Here’s a case in point. We know that dams create havoc in the lives of free flowing rivers. Often, the lakes formed behind the dams also become sterile waters in comparison. Part of this effect comes from drawdown, the inevitable drop in water level that comes about in order to feed electrical generating turbines or to divert water for irrigation of crops. The filling and dropping of the water level creates a sterile life zone because neither aquatic nor terrestrial plants and animals can consistently maintain themselves in this changing zone. Some have referred to this dead zone as the “bathtub ring” effect, shown here in the top left image. Pairing that photograph with another shot of a free-flowing river and the variety in a riparian life zone can be a very effective way of convincing people that a dam is destructive.

The impoundment behind dams is very often a sterile life zone because of drastic water fluctuations. Drawdown of water levels in these reservoirs creates this “bathtub ring” effect, a zone where life cannot take hold because of frequent changes in water level.

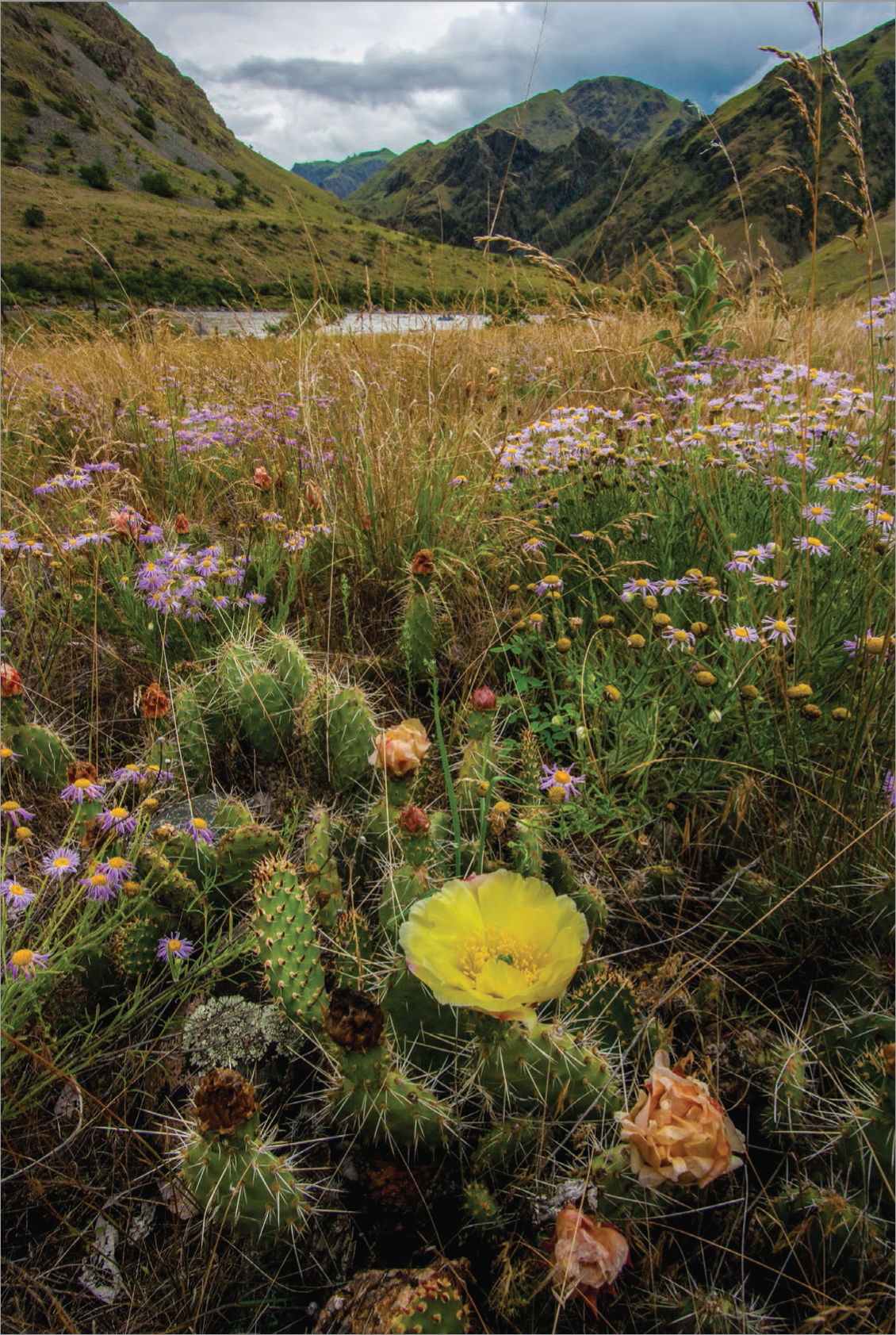

On a free-flowing river, plants thrive along the shores and provide both habitat and food for numerous species. This was shot at almost ground and water level with a 20mm ultra-wide lens to emphasize the grasses along the shore and the clarity of the water. This was the Teton river in Idaho before a dam drowned it.

This photo was made with a 10–22mm zoom at 12mm. The extra-wide view and great depth of field helped show the Snake River in the background and the grasses and flowers along the shore. Hells Canyon, deepest gorge in America.

Logging. Worldwide, forests are being cut for various commercial purposes. The loss of forests has a large impact on global warming because trees sequester carbon through photosynthesis, reducing the greenhouse contributor carbon dioxide on a large scale. In addition, massive logging destroys vital habitat for numerous species. In Borneo, one of the major species on the brink of extinction is the orangutan. In my presentations, and in books and magazines, I pair certain Borneo photos to drive home the point of critical habitat loss (see facing-page images).

Indirect Signs and Effects. As a documentary photographer you should also look for indirect messages about what is happening to the environment in a given region. After one of my flights to the Amazon Basin of Peru, I photographed boxes of chainsaws being off-loaded from the plane at Puerto Maldonado. In an indirect way, it shows what’s happening to some of the rainforest in the region.

In Borneo, vast acreages have been logged to create palm oil plantations because of worldwide demand for the product. Palm oil is an ingredient in many processed foods.

The habitat loss for orangutans is reducing their numbers at an appalling rate. Once numbering in the hundreds of thousands across Borneo and Sumatra, recent habitat loss in the past has reduced populations by at least 50 percent—and they are now classified as an endangered species. This female and days-old youngster may be luckier than most, residing in forest protected as Tanjung Putting National Park in Indonesian Borneo.

Boxes of chainsaws off-loaded from a plane in Puerto Maldonado in the Amazon Basin region of Peru. Does this tell you what’s happening to the rainforest in the region? Photos like this can get the message across as strongly as pictures of a ravaged rainforest.

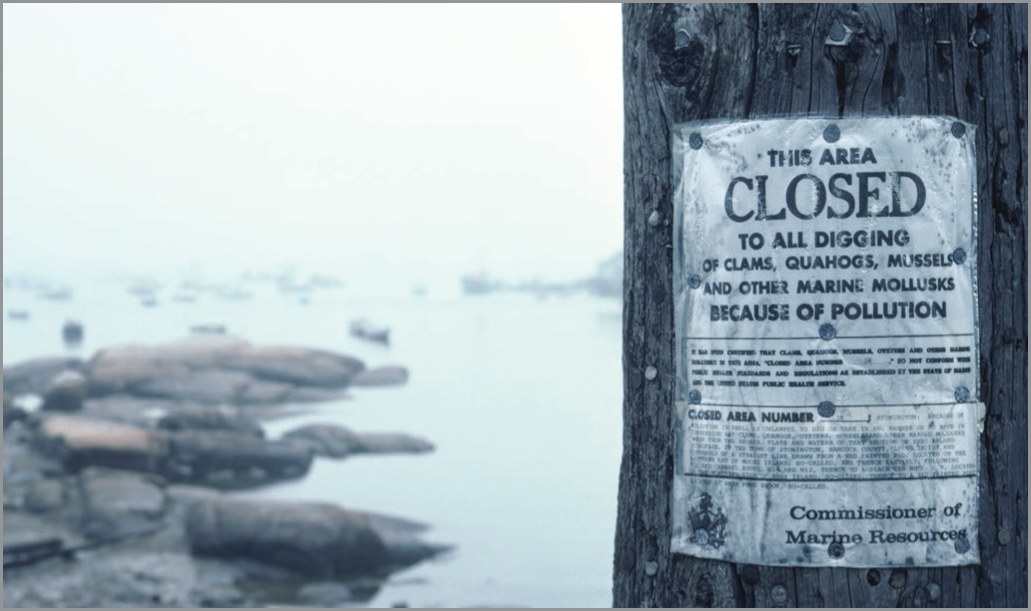

Signs also can be indicative of something wrong in the environment. Sometimes it’s not possible to photograph pollution because it may be in an invisible (but still toxic) form. I photographed the sign in the photo to the right on a dock in Stonington, ME. This region is famous for its seafood, but I didn’t order any clam chowder at a local restaurant. This photo was made in 1982, and I hoped that this pollution had been cleaned up since then because I love New England clam chowder. Alas, I went to the State of Maine Department of Marine Resources website and found Stonington mollusks still should not be eaten. Moreover, there were more than sixty other places on the Maine coast listed as polluted.

This photo was made in 1982 in Stonington, ME—a region famous for its seafood.

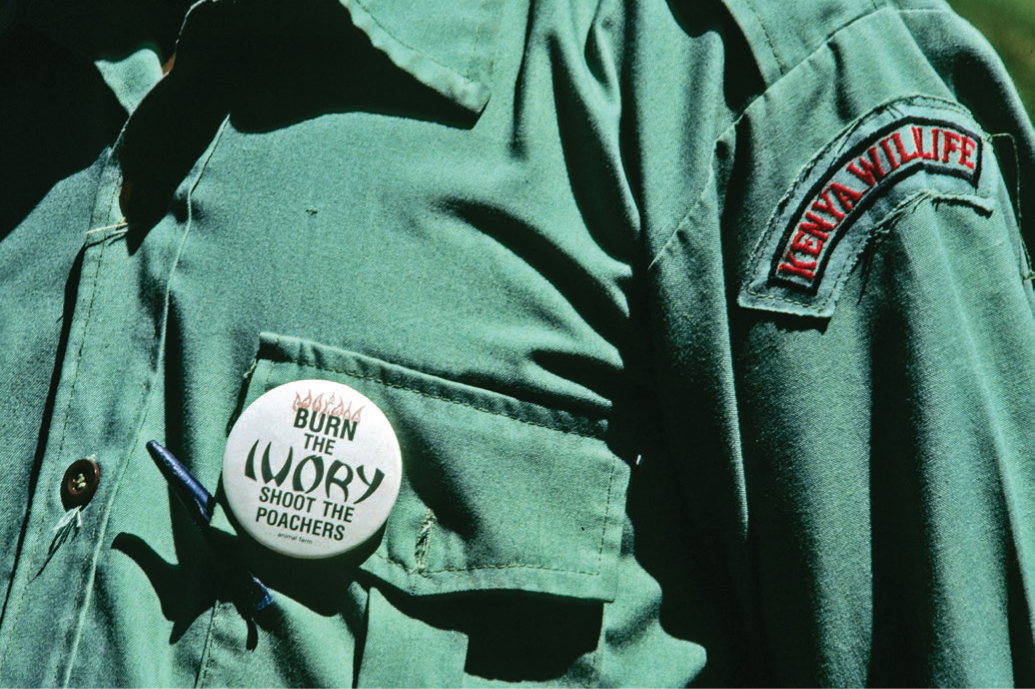

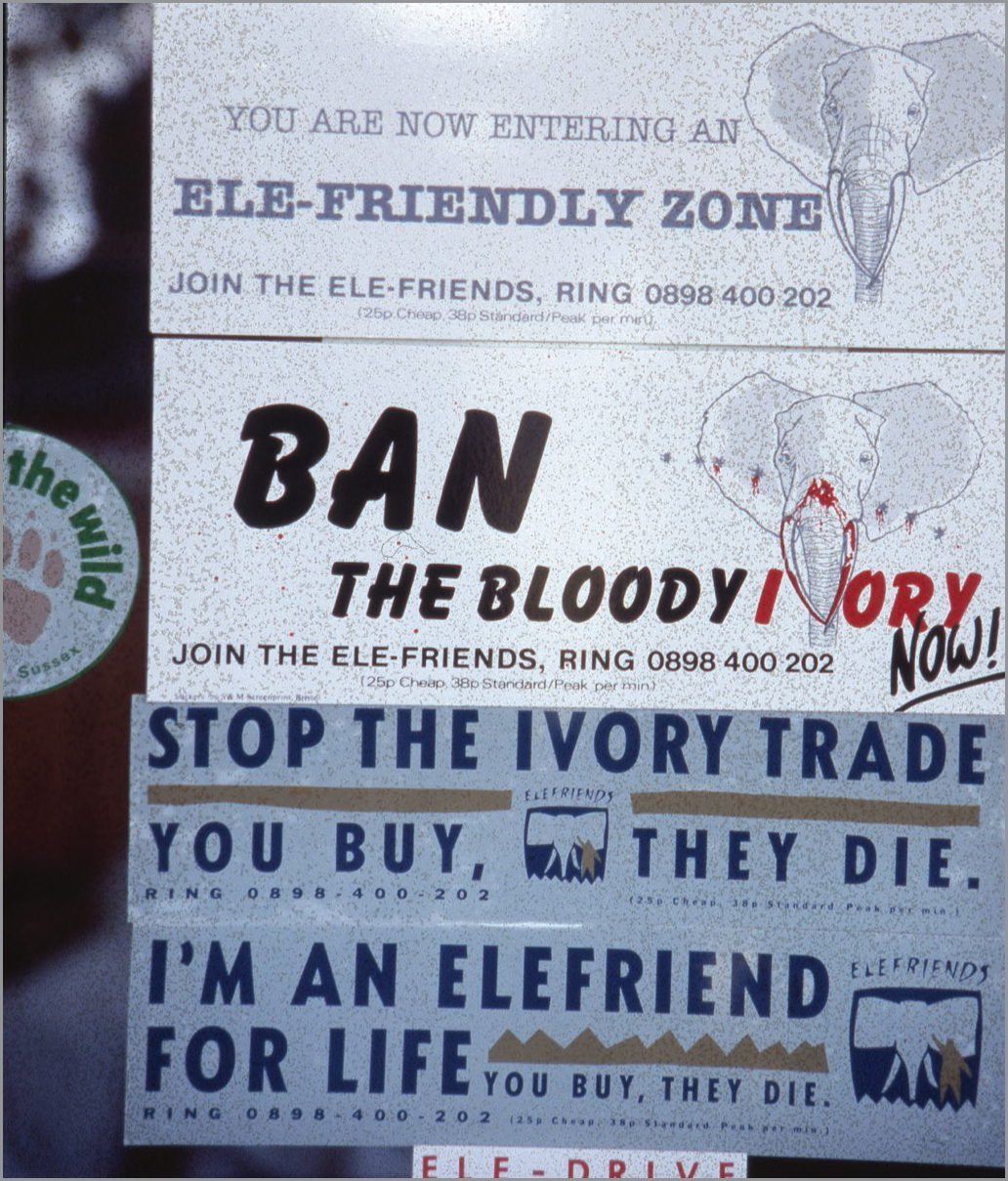

Poaching. Sentiments ran high during the late 1980s and early 1990s in Kenya when elephant and rhino poaching was rampant. I photographed this badge (left) worn by anti-poaching rangers in the Kenya Wildlife Service.

An anti-poaching ranger wears a badge reflecting the sentiment when elephant and rhino poaching was rampant across the country.

An elephant killed by poachers ten days earlier in Tsavo National Park in Kenya. This photo was made in 1990 when Kenya had been losing thousands of elephants every year. It was bad then but it’s worse now across Africa.

A sign in the office window at the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust outside Nairobi, Kenya. Baby elephants and rhinos orphaned by poachers are nursed back to health and eventually released back to the wild. The effort is not always successful.

Irony can be powerful but with some photos it only becomes clear with accompanying captions. This was made on Yarki Island at the northern tip of Lake Baikal in Siberia a place of great beauty, revered by most Russians. I shot the photo behind the cabins used for summer field studies by ecology students at the University of Irkutsk.

A Colorado mountain stream was polluted by runoff from mine tailings left behind when the mine was abandoned. Farther down the mountain, this stream and other streams tainted by mine tailings empty into the Animas River, which is hyped as a great trout fishing stream. I think I’ll pass on a trout dinner from this river. Mercury, cadmium, and arsenic anyone?

Litter. Lake Baikal in Siberia is one of the world’s most beautiful spots and a source of Russian pride. In my early travels there I worked with a team of Russian and American ecologists in the early 1990s to have Baikal declared a World Heritage Site (it was so declared in 1996). I made the top-right photo on Yarki Island at the northern tip of the lake. The irony of it is that I shot it behind the cabins used for summer field studies by ecology students at the University of Irkutsk.

Mining. I live in Colorado and I don’t have to travel far to see and photograph the destructive effects of mining on the land (bottom right). In many cases, the problem is not just the mining operation itself but also the aftermath. Many of these mines were started in the mad gold and silver rush days of the 19th century and carried over into the 20th century. Most were abandoned when the gold or silver ran out. These tended to be underground mines, so the surface damage was far less than open pit mines. However, the tailings left behind have become major sources of pollution as the exposed minerals leach out. Some of these toxic elements in the tailings include arsenic, mercury, cadmium, and certain radioactive minerals.

In the early 1970s, when I participated in DOCUMERICA (see chapter 2), I learned of some ranchers in northern Montana who were fighting to keep their lands from being strip-mined for coal. Due to a quirk in state laws, they did not own the rights to the minerals under their ranches. They were under siege by mining companies to strip mine their land for those coal deposits beneath the fertile grasslands. I spent considerable time with a couple of ranchers documenting both their way of life and the ugly scars of open pit mines inching toward their ranches. I included the human element in my documentation because people are a part of the equation in environmental threats. The Redding family had three generations living on this ranch—Bud (the father), John (the grown son), and Rial (the youngster who would presumably inherit this ranch if it were left untouched).

This documentation took place more than four decades ago. Since then, I have tried to find out what happened and I have been unsuccessful in tracing the Redding family. I appeal to you, the reader, to take it as an assignment to visit the region (contact me and I’ll give you information about the locale) and continue this documentation. Is the ranch still there? Or did the mining company win out? My DOCUMERICA photographs are free to use from the National Archives website, now on flickr (www.flickr.com/search/?q=boyd%20norton). With updated photos of the area, it’s a story waiting to be told.

Fracking. Currently, a controversy rages over fracking in various parts of the country. Is it safe? What are the dangers (groundwater contamination, for one)? How do you portray the downside of fracking? These are some of the challenges facing a conservation photographer today. Fracking takes place underground and those impacts cannot be seen. However, there are some things that are visible in certain places. Methane released from fracking has leaked into underground water supplies, causing the tap water in nearby homes to become flammable. Video and still photos have shown flames coming out of faucets. Part of the story.

It is important to have good captions with your pictures. This can and should be done in the metadata during the time you process your digital images.

So what should you photograph? Think story.

1. Do your research carefully.

2. Document the good, the bad, and the ugly.

3. Document beautiful places and the details of elements within them.

4. Document the destruction wrought by mining, logging, dams, and other developments.

5. Photograph signs that indicate dangers.

6. Use ultra-wide lenses to relate an ugly foreground to a beautiful background (or vice versa).

7. Include the human element—people affected by the destructive developments.

8. Document people enjoying wild nature in parks and reserves.

John Redding holds a chunk of coal of the kind that lies below their threatened ranchland. His father Bud looks on.

I photographed John Redding (L) and Bud Redding (R) to add a human element to the conservation story. I shot near dusk, when the lighting gave a lovely soft glow to the ranchlands and chose a 100mm focal length with a large aperture so the background would look almost painterly.