FOOD DESERVES a chapter of its own because in terms of carbon footprints it is such an important but poorly understood area. The various food entries early in this book have covered many of the key points, but this chapter briefly pulls together all the main issues to give a sense of the food sector overall. Most of the estimates in this section have come from my work over several years for Booths, a U.K. supermarket chain. Some of the specifics of the food you buy will depend on where you live in the world, but the principles are largely transferable.

As we saw earlier, in the developed world, the food we buy adds up to around 3 tons CO2e per year.1 In the U.K. that’s 170 million tons CO2e per year or 20 percent of the average annual total footprint and nearly as much as household fuel and electricity put together. In North America, it is likely to be a lower proportion, since the average per capita is nearly double the U.K. figure. If you factor the effect of deforestation, the footprint of our food goes up again to a staggering 30 percent of the U.K. total. Interestingly, food is also a very expensive part of our footprint. If you want to trash the planet, buying the wrong food or wasting what you buy is a far more expensive way of going about it than leaving the lights on or turning up the thermostat.

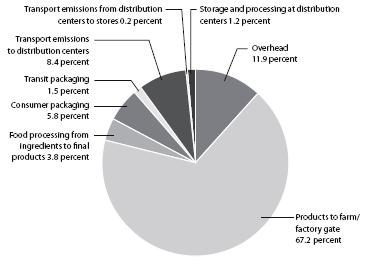

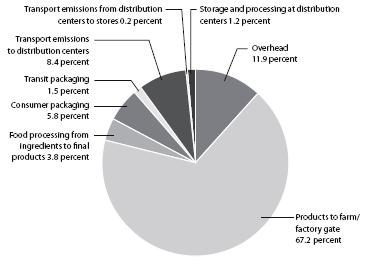

FIGURE 12.1: Total footprint of Booths products and supply chains: 226,000 tons CO2e.

How the footprint of food breaks down

Figure 12.1 shows an estimated breakdown of the footprint of food at the point when it leaves a Booths. This is just a best estimate. As the chart shows, two-thirds of the impact is on the farm. Transport is a big deal for some products but not most. The supermarket’s own operations make up about one-ninth of the total picture.

Farms

Whereas CO2 is the dominant greenhouse gas overall, it accounts for only 11 percent of agricultural emissions.2 The rest is nitrous oxide (53 percent) and methane (36 percent). Nitrous oxide is 296 times more potent per pound than CO2 as a climate-change gas, and on farms it results mainly from the use of fertilizer but also from cattle pee, especially if there is excessive protein in their diet, and from the burning of biomass and fuel.3 Methane, which is 25 times more potent than CO2, is mainly emitted by cows and sheep when they belch. Some is also emitted from silage. The CO2 comes from machinery but also from the heating of greenhouses to grow crops out of season or in countries that just don’t have the right climate.

Transport

The first thing to say about transport emissions is that, for all the talk that we hear about food miles, they are not the most pivotal thing to think about. At Booths, over one-quarter of the transport footprint comes from the very small amount of air freight in their supply chains—typically used for expensive items that perish quickly. Conversely, most of their food miles are by ship (partly because the U.K. is an island), but because ships can carry food around the world around 100 times more efficiently than planes, they account for less than 1 percent of Booths’ total footprint. The message here is that it is OK to eat apples, oranges, bananas, or whatever you like from anywhere in the world, as long as it has not been on a plane or thousands of miles by road. Road miles are roughly as carbon intensive as air miles, but in the U.K. the distances involved tend not to be too bad, whereas in North America they can be thousands of miles. Booths is a regional supermarket with just one warehouse, so their own distribution is not a big carbon deal, and they have been working hard on further improvements.

Meat and dairy

Food from animals turns out to be more carbon intensive (remember, this is my shorthand for greenhouse gas intensive) than food from plants, simply because animals are inefficient devices for producing food. They eat plants and then spend their lives wasting most of the energy from them on things such as walking around and keeping warm. It is a far more efficient process for humans to eat plants directly, so that all the plant energy can go directly to us. Beef and lamb are doubly high in carbon because they are belching ruminants. Chicken is a bit better because, to put it bluntly, they don’t live as long, so they don’t get so much opportunity to waste the energy in their feed.

Dairy has all the same problems of ruminant meat production, so there is little point in switching from beef to cheese. A kilo (2.2 pounds) of cheese comes in at around 13 kg CO2e, compared with around 17 kg for beef. Milk comes in at around 1.3 kg per liter or quart.

Hothouses

Protected crops can have just as high an impact as air-freighted foods. It takes a huge amount of energy to keep a greenhouse warm enough to grow tomatoes during the winter (see kg (2.2 lbs.) of tomatoes).

Packaging

This topic needs to be kept in perspective. It’s only about 6 percent of what you should be considering as you shop. And at its best it serves a purpose, helping food to stay fresh and letting you know what you are buying. Indeed, a simple bag can dramatically improve the shelf life of some fresh foods.

At Booths we found that no single material dominated the packaging footprint, and there were some surprises.

> Paper and cardboard are often more carbon intensive than plastic packaging, mainly because making paper is so energy intensive but also because it emits methane if it ends up in landfill.

> Plastic is environmentally nasty as either landfill or litter because it hangs around for so long. However, it is typically not quite as energy intensive to produce as card packaging and has the advantage, from a purely carbon perspective, that when you put it in landfill, you are just sending those hydrocarbons back into the ground where they came from for long-term storage. In the days when supermarkets routinely gave out disposable plastic bags, they accounted for around one-thousandth of the footprint of a typical shopping trip. Biodegradable plastic can be a well-intentioned nightmare, clogging up recycling processes, with the potential to ruin a whole batch. In landfill it rots, emitting methane.4

> Glass is energy intensive to make (or recycle), and its weight adds to the transport footprint. Cans of beer are better than bottles, as are cartons or boxes of wine. Incidentally, bottles are absolutely no better for storing wine than the more climate-friendly alternatives.

> Steel and aluminum are carbon-intensive stuff, but you don’t need a great weight of them, and they’re easy to recycle. It takes only about one-tenth of the energy to recycle aluminum compared with extracting it from ore in the ground.

Food waste

In the developed world we are thought to waste about one-quarter of the edible food we buy.5 This figure depends partly on your definition of what was edible in the first place. Do you think of the potato skin as just packaging, or do you think of it as the tastiest and most nutritious bit? Whatever your definition, a huge and expensive proportion of our food gets left on plates, is allowed to go off in the fridge, isn’t scraped out of the pan properly or isn’t picked off the carcass. It is slightly better to compost waste food than to throw it into landfill, but it doesn’t get you away from the main issue that the carbon footprint of that food has been needlessly incurred.

Refrigeration

Fridges use electricity, and it takes energy to make them in the first place. On top of that is the problem that traditionally they have relied on the use of refrigerant gases that have a global warming potential several thousand times that of CO2. This stuff tends to leak out of large commercial fridges, which need topping up regularly. At Booths, this leakage from within the stores and warehouse accounted for around 3 percent of the total footprint. And refrigeration accounted for about half of all electricity usage in stores. When all considerations are taken into account, refrigeration probably accounts for around 6 percent of the footprint of supermarket food.

There are huge strides being made in cooling technologies. These include the use of other gases with dramatically lower global warming potential,6 the reuse of spare heat to warm the stores, and the use of underground cooling pipes. Booths is starting to employ CO2-based refrigeration systems (thereby almost eliminating the climate change impact of gas leaks) and expects to have replaced almost all its fridges with these within a decade. The company is also reusing the heat in their newest stores. Thanks to these kinds of approaches, we can expect the footprint of commercial refrigeration to fall dramatically. In the meantime, do not let it put you off your fresh, chilled produce.

The following is a quick summary of the various steps you can take to reduce the carbon footprint of your diet—and the type of savings you can expect.

Eat what you buy. Ask people how much they would like before you serve them. Eat the skins. Clean the plates, pick the carcass. Save the leftovers. Check what needs to be eaten when you plan your menus. Keep vegetables in the fridge if you can. Rotate the contents of your cupboards so that old stuff is at the front. Eradicating waste is worth a 25 percent savings for the average shopper.7

Reduce meat and dairy. I’m not saying go vegan any more than I’d say never drive. But there is no dodging the fact that meat and dairy are key areas. By reducing our consumption of these food types, many of us will live a bit longer and save money as well as reducing our emissions. The vegetarians and vegans I know don’t consider it a hardship. Sensible reductions in meat and dairy without needing to go vegetarian are probably worth another 25 percent savings on a typical diet.

Go seasonal, avoiding hothouses and air freight. Local, seasonal produce is best of all, but shipping is fine. As a guide, if something has a short shelf life and isn’t in season where you live, it will probably have had to go in a hothouse or on a plane. In the U.K., Canada, and more northern parts of the U.S., in January, examples are lettuce, asparagus, tomatoes, strawberries, and most cut flowers. Apples, oranges, and bananas, by contrast, almost always go on boats. Adopting this tip religiously can probably deliver a 10 percent savings on a typical diet.

For more specific information, try the following:

> The Eat Well Guide to seasonal food in different U.S. states and Canadian provinces: www.eatwellguide.org/i.php?id=Seasonalfoodguides

> Epicurious’s interactive seasonal recipe map of the U.S.: www.epicurious.com/articlesguides/seasonalcooking/farmtotable/seasonalingredientmap

> Food Down the Road’s simple chart showing Canada’s seasonal foods by month: www.fooddowntheroad.ca/online/seasonalfoodchart.php

Avoid low-yield varieties. Cherry tomatoes and baby corn are classic examples. Estimated savings: 3 percent.

Avoid excessive packaging. Some packaging serves a valid purpose in keeping food fresh. But a metal dish inside plastic trays inside a plastic bag within a cardboard box is probably excessive. Worth around 3 to 5 percent.

Recycle your packaging. Worth 2 to 3 percent.

Help the store reduce waste. Always take from the front of the shelf so that the stock can be rotated. Handle food with care. Buy the reduced-price items when you can, but don’t hang around waiting for them to be reduced. Worth perhaps a 1 percent savings.

Buy misshapen fruit and vegetables. Stimulate demand for the huge quantities of produce that get thrown away just because of their shape. The savings are hard to quantify, but perhaps 1 percent.

Lower-carbon cooking. Use a pan lid whenever you can. Remember that water boils at the same temperature however much heat you apply, so for cooking food, a gentle boil is just as fast as a furious one. Use a microwave when appropriate. Perhaps a 5 percent savings.

Incredible! The savings here add up to about 75 percent. Sadly the math doesn’t work out quite like that because some of these points overlap. If you do them all, they work out to more like a 60 percent savings—still a remarkable amount.