2

The Origins of Scholarship on the Fourfold Gospel

From Alexandria to Caesarea

Works1 of great ingenuity do not emerge from a vacuum but typically are an improvement upon existing technologies, or the creative realization of previously unforeseen combinations of existing factors. So it was with Eusebius’ Canon Table apparatus. As he himself acknowledged, his scholarly project built upon the work of a prior Alexandrian author by the name of Ammonius. Ammonius’ composition, which I will argue was titled the Diatessaron-Gospel, has left no trace in the manuscript tradition,2 with the result that for information about it we are wholly dependent on the short description provided by Eusebius himself in his Letter to Carpianus. Because Eusebius mentions his predecessor’s work in the context of introducing his own Canon Tables, scholars have long recognized some sort of connection between the two figures. However, among those who have previously commented on them there has been a lack of clarity regarding the precise relationship between their respective works, with some using ambiguous terminology that blurs the distinction between the Diatessaron-Gospel and the Canon Tables, and others arguing incorrectly that the two works had nothing in common. Hence, in what follows I intend to highlight and give a more nuanced account of the distinct contributions of these two figures in what was a joint scholarly enterprise stretching over a century or more, which represents the earliest thorough investigation of the patterns of similarity and difference that exist within the fourfold gospel canon.

The first half of this chapter is an attempt to identify Ammonius and contextualize his literary endeavours based on the meagre evidence that can be gleaned from the historical record. Although conclusive proof is lacking, I argue that it is probable that this Ammonius was the teacher of Origen in Alexandria and also a Peripatetic philosopher famed for his philological scholarship.3 If so, then Origen’s well-known Hexapla and Ammonius’ Diatessaron-Gospel were most likely parallel attempts at using cutting-edge scholarly tools to analyse the emerging Christian canon of sacred texts. In the second half of the chapter I pivot to Eusebius and survey the various uses of tabular methods across his corpus in order to show how these novel experiments in information visualization provided him with the insights that enabled him to build upon—or, more precisely, improve upon—Ammonius’ earlier work on the gospels. By using Ammonius’ composition as the raw materials for his own Canon Tables, Eusebius became the channel for the transmission of Alexandrian philological scholarship to the wider Mediterranean world of late antiquity.

The Diatessaron-Gospel of Ammonius of Alexandria

Who was Ammonius?

Given its highly specialized focus, Ammonius’ work on the gospels probably found a small audience in the third and fourth centuries, so its circulation was surely limited. This observation helps to explain why the only description of it is found in Eusebius’ Letter to Carpianus, in which the Caesarean historian lays out the origin and function of his system of Canon Tables (see fig. 18). Here Eusebius gives no further biographical details about his predecessor beyond the fact that he was from Alexandria (Ἀμμώνιος ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεὺς).4 However, in his Ecclesiastical History, Eusebius also mentions an Alexandrian Ammonius who composed, among other works, a treatise titled On the Harmony of Moses and Jesus (Περὶ τῆς Μωυσέως καὶ Ἰησοῦ συμϕωνίας). This Ammonius, the historian tells us, was ‘highly esteemed among many’ (παρὰ τοῖς πλείστοις εὐδοκιμοῦντος), and his works were still in circulation among the ‘scholarly’ (παρὰ τοῖς ϕιλοκάλοις) in the early fourth century.5 The fact that in the Letter to Carpianus Eusebius offers no further information about the Ammonius engaged in study of the gospels may indicate that he knew nothing else about this figure. However, it is more likely that he is brief in his mention of Ammonius because he assumed his readers would already know of his identity, a supposition that coincides well with the reported fame of the Ammonius responsible for On the Harmony of Moses and Jesus.

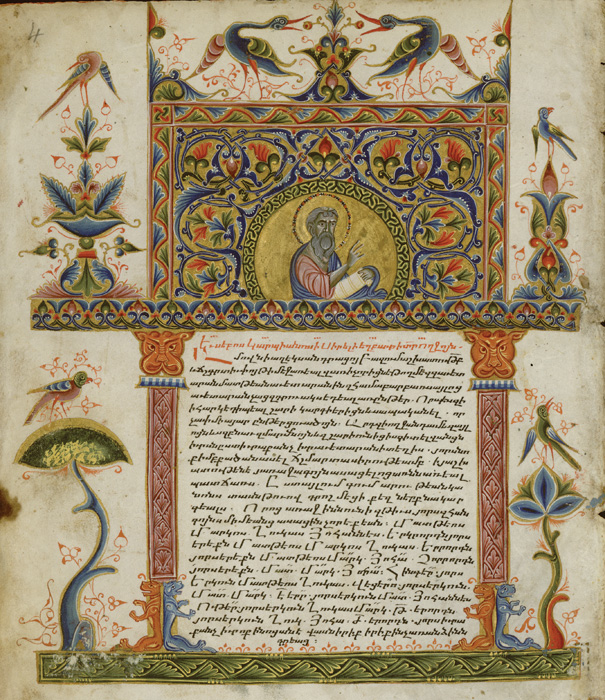

Fig. 18. Portrait of Eusebius above the beginning of his Letter to Carpianus in the Gladzor Gospels (c.1300). The facing page of the manuscript contains a matching portrait of Carpianus above the latter half of the letter.

Gladzor Gospels, Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA, Armenian MS 1, p. 4

A further argument for the attribution of the two works to the same Ammonius is their common theme. Eusebius does not tell us why Ammonius composed his work on the gospels, but it likely was the same as Eusebius’ own intent behind the Canon Tables, namely, to show the harmony and agreement of the evangelists. Similarly, Ammonius’ other work was focused on presenting the συμϕωνία between Jesus and Moses. Common to both the relationship of Jesus to Moses and the interrelations of the fourfold gospel is the possibility of discord which threatens to undermine divine truth, an Achilles heel exploited by Christians such as Marcion, as well as by pagan critics like Celsus. It is plausible, therefore, that a second- or third-century Christian engaged in this intellectual milieu might deem it necessary to demonstrate both the ‘harmony’ of Moses and Jesus and of the four separate accounts of Jesus’ life. It is best, therefore, to assume these two Ammonii—the one mentioned in the Letter to Carpianus and the one referred to in the Ecclesiastical History—are one and the same, a conclusion already reached by Jerome in the later fourth century who, almost certainly relying on Eusebius, gave a brief notice of a single Ammonius in his De viris.6 I will therefore proceed on the assumption that the report about Ammonius in the Ecclesiastical History sheds light on the person whose work served as the most direct inspiration for Eusebius’ Canon Tables.

Saying more about this Ammonius, however, necessarily enters into more contested territory. Indeed there is an ongoing, and perhaps at some level irresolvable debate over the identity of the Ammonius discussed in Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History. The relevant passage in the Ecclesiastical History occurs in Eusebius’ narrative of Origen’s life and work. The Caesarean historian quotes a section from Porphyry’s treatise against the Christians in which the Neoplatonic philosopher asserted that Origen had been a ‘hearer’ (ἀκροατής) of an Ammonius who was renowned for his philosophical learning. Porphyry then used Ammonius as a (in his view) positive contrast with Origen: whereas Ammonius began life as a Christian and gave up his faith to learn philosophy, Origen received philosophical training, but turned his back on it to live as a Christian. In response to this extract from Porphyry, Eusebius asserts that Origen was in fact a Christian from his youth, and that Ammonius remained a Christian until the end of his life, as evidenced by his many works that were still in circulation, such as On the Harmony of Moses and Jesus.7

There are three main options for interpreting this passage. Probably the most common view in scholarship has been to interpret Porphyry’s statement to mean that Origen was a student of the Platonist Ammonius Saccas, who also taught Plotinus, Porphyry’s own instructor, and that Eusebius simply confused a Christian named Ammonius with the non-Christian Platonic philosopher. If this line of thinking is correct, then there is little more we can say about our Ammonius in the way of a more precise date for his flourishing. Theodor Zahn, representing this position, observed that Eusebius spoke of Ammonius as someone who had neither died recently nor been in the distant past, and so placed his literary activity in the years 240–280 ce, making him a younger contemporary of Origen, who died in the mid-250s.8 Photius claims that an Ammonius served as bishop of Thmuis and was visited by Origen, and this figure could have been the Christian Ammonius whom Eusebius confused with the philosopher, though this theory is not without problems.9

If, however, Eusebius was correct in supposing that the Ammonius who Porphyry says was Origen’s philosophical teacher also composed these two works of a Christian character, then there are at least two further possibilities. It may be, as Elizabeth DePalma Digeser has recently argued, that Ammonius Saccas himself dabbled in Christian topics and so was responsible for the Diatessaron-Gospel, though no other ancient sources make any mention of such literary activities.10 In her reading, the two named Christian works of Ammonius coincide well with later reports that attribute to Ammonius Saccas the achievement of harmonizing Plato and Aristotle. The final solution has been argued most clearly by Mark Edwards, who pointed out that, in addition to Ammonius Saccas the Platonist, there is also attestation of a further Ammonius who lived around this same time and was regarded as a Peripatetic. The Peripatetic Ammonius, who was praised by Longinus as one of the two ‘most erudite men of their epoch’,11 must have flourished in the last decades of the second century, and so would have been an older contemporary of Origen who could have served as his teacher.12

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to settle this debate, if it is even possible to do so with a satisfying degree of certainty.13 Moreover, on any of the above solutions the main conclusions of this chapter should hold true, since any of the proposed Ammonii would have been a contemporary of Origen, and, as I shall argue below, Origen’s Hexapla provides us with the closest parallel for Ammonius’ Diatessaron-Gospel, illuminating the format and the scholarly context of this work. For my purposes the question then becomes one of priority. If Eusebius confused two distinct individuals, then the Christian Ammonius was perhaps later than Origen, and the Diatessaron-Gospel may have been modelled on the earlier Hexapla. If, on the other hand, Eusebius was correct that Origen’s instructor in philosophy also composed Christian works, then it is more likely that Ammonius’ scholarship on the gospels provided an impetus for Origen’s text-critical work.

My own sympathies lie with Edwards’ position, particularly in the light of his observation that Eusebius had access to a great many more sources, especially about Origen’s life and career, than we ever will, and that we should trust his report unless there are good reasons not to do so.14 For this reason I incline to the view that Origen’s teacher composed the Diatessaron-Gospel, and will proceed on this basis. Moreover, though I need to delay the discussion slightly, we will see that the reported fame of the philological skills of the Peripatetic Ammonius coincides well with what we know about Origen’s Hexapla and the Diatessaron-Gospel, making him a more likely candidate for Eusebius’ source than the Platonist Ammonius Saccas, whose tradition of philosophy, represented preeminently by Plotinus, scorned such philological investigations as unphilosophical. If it seems implausible to some that a Peripatetic philosopher held in such high regard by Longinus also composed works focused on Christian texts, one needs only to recall that Porphyry himself, regardless of which Ammonius he had in mind, asserted that Origen’s philosophical teacher began his life as a Christian but later went on to attain ‘the greatest attainments in philosophy’. In other words, Eusebius’ contention that Origen’s teacher of philosophy composed Christian works cannot be construed as merely an ambit claim from a Christian author attempting to create a past more intellectually respectable than the one that existed, since Porphyry, the most famous ancient critic of Christianity, himself testifies to the one-time Christian faith of a teacher who was held in the highest regard by non-Christian philosophers like himself. Following Porphyry’s lead, we might then suppose that the two works of a Christian nature that we can ascribe to this Ammonius were composed early in his life before he forsook his childhood faith to live as an adherent of traditional Greek religion.15

Eusebius’ Description in the Letter to Carpianus

It is significant that when Eusebius came to describe his system of Canon Tables, he did so by situating his project in the tradition going back to Ammonius. He could have drawn upon his predecessor’s work without acknowledging his intellectual debt to his forebear, as so often happened in antiquity. The fact that he did not do so was probably due to his genuine esteem for Ammonius’ accomplishment. Having found out himself how complicated this issue could be, the first thing Eusebius did when introducing his Canon Tables to the world was to tip his hat to the ‘hard work and study’ (ϕιλοπονίαν καὶ σπουδήν) exerted by Ammonius in his analysis of the gospels. He then provided a one-sentence summary of the work, which is our sole surviving description of Ammonius’ composition:

He has left behind for us the Diatessaron-Gospel, in which he placed alongside the [Gospel] according to Matthew the concordant sections from the other evangelists.

τὸ διὰ τεσσάρων ἡμῖν καταλέλοιπεν εὐαγγέλιον, τῷ κατὰ Ματθαῖον τὰς ὁμοϕώνους τῶν λοιπῶν εὐαγγελιστῶν περικοπὰς παραθείς16

The verb καταλείπω is one of the four standard introductory formulas Eusebius employed in his Ecclesiastical History to refer to the works of previous authors, and when used in conjunction with ἡμῖν, as it is here, it usually indicates that he himself had access to the work in question.17 This description is frustratingly brief, but is nevertheless sufficient to let the reader discern the main contours of Ammonius’ work, which must have been broadly akin to a modern gospel synopsis with parallel passages from the gospels presented in columns.18 The arrangement of this text in columns is indicated by the verb παρατίθημι, which was often used in antiquity to refer to a multi-columned work.19 The one other feature of the work that Eusebius clearly tells us is that the arrangement of the text gave priority to the first gospel—Ammonius dissected the latter three gospels in order to align the parallels he found there with corresponding passages in Matthew. Thus, some Matthean passages would presumably have had corresponding material in three parallel columns (representing Mark, Luke, and John), but many would have included text in fewer columns, probably leaving the columns empty when there was no related material from a given gospel.20 Ammonius’ choice of Matthew as his base text is notable and must have been a deliberate decision, probably related to Matthew’s position at the head of the fourfold gospel canon.

Eusebius does not tell us what Ammonius did with passages from Mark, Luke, and John that had no correlates in Matthew, so any conclusions drawn on this question are speculative. Adolf von Harnack suggested that the fact that Eusebius calls the work τὸ εὐαγγέλιον implies that the remaining material from these latter three gospels was probably also included.21 Moreover, Eusebius does not criticize Ammonius for leaving out this bulk of material, even though, as we shall see, he was critical of other aspects of his predecessor’s work. These two observations may suggest that this non-Matthean material was included, but, if so, it is difficult to say how he presented it. All that is certain is that, if this other textual content was included, it must not have interrupted the continuous flow of Matthew’s text, since Eusebius claims only that the narrative sequences of the latter three were disrupted.

We should linger for a moment over the title Eusebius gives for Ammonius’ composition. In his brief account in De viris Jerome calls it the Euangelici canones, but his account is clearly derivative from that of Eusebius so it seems unlikely that he had actually seen Ammonius’ composition.22 Instead, he was clearly borrowing the title of Eusebius’ own Canon Tables and applying it retrospectively to Ammonius’ earlier work. In contrast, it is quite likely that in this passage from the Letter to Carpianus Eusebius gives us the actual title that originated with Ammonius: τὸ διὰ τεσσάρων εὐαγγέλιον. Of course, this is the same title that Eusebius also gives for the more famous composition of Tatian, the so-called Diatessaron. I will say more about Tatian’s work shortly. For now we should consider how this title might relate to the work of Ammonius.

Interpreting the title of Ammonius’ composition largely centers on how one should understand the preposition διά. Here there are at least three possibilities. First, it has long been supposed that the phrase διὰ τεσσάρων alludes to classical musical theory, specifically the interval of a fourth, one of the various possible συμϕωνίαι.23 Though somewhat late, Boethius is a good representative of this tradition, referring to the symphonia diatessaron, quae princeps est.24 If we recall that Ammonius, according to Eusebius’ history, also composed a work aimed at demonstrating the συμϕωνία between Moses and Jesus, the possibility of a musical background for the phrase διὰ τεσσάρων is strengthened. There are, however, at least two other possibilities that must be considered.

A second explanation comes from the fact that some sources attest the use of διά to indicate the material out of which something is made.25 For example, Diodorus Siculus speaks of ‘images made from ivory and gold’ (εἴδωλα δι᾽ ἐλέϕαντος καὶ χρυσοῦ), and Plutarch mentions sacrifices ‘made with flour, drink-offerings, and the least costly gifts’ (δι’ ἀλϕίτου καὶ σπονδῆς καὶ τῶν εὐτελεστάτων πεποιημέναι).26 In keeping with these parallels, the title τὸ διὰ τεσσάρων εὐαγγέλιον could imply that the four gospels were Ammonius’ source material, and the result of his editorial labour was a εὐαγγέλιον constructed from these four parts.

A third possibility is that διά here might be referring, not to Ammonius’ source materials, but rather to some formal characteristic of his work. For example, Athenaeus in the third century noted that Timachidas of Rhodes wrote a treatise on banquets ‘in epic verse (δι’ ἐπῶν) in eleven or possibly more, books’.27 Here διά indicates not the source of Timachidas’ work, but rather its format or style of composition. Similarly, Eleanor Dickey pointed out that discussions of spelling in antiquity ‘normally use the formula διά + genitive’, such as in the phrase διὰ τοῦ α γράϕεται which means ‘it is written with an α’.28 Here the comparison with Origen’s Hexapla becomes relevant, because one of the best surviving descriptions of the work uses διά in this sense. As is well known, the Hexapla consisted of between six and eight texts arranged in parallel columns, including the Hebrew text of the Old Testament, a Greek transliteration of the Hebrew text, and as many Greek translations as Origen had available for any given book, using the Septuagint, Aquila, Symmachus, and Theodotion as a core. Two surviving fragments of the Hexapla for the psalms have confirmed this layout of the work, and they show that Origen allowed only one word per line, maximizing the potential for comparative analysis.29 Origen’s Hexapla is justly famous and known primarily because of its importance for textual criticism of the Old Testament, and also for its enormous scholarly achievement, given that the complete work may have filled nearly forty codices of 400 folios each.30

By calling his work the Ἑξαπλᾶ, Origen was highlighting its most distinctive feature, namely its format, consisting of six parallel columns. As Rufinus stated, ‘on account of this manner of composition, he [i.e., Origen] called the exemplar itself Hexapla, which means “written in sixfold order”’ (propter huiuscemodi compositionem exemplaria ipsa nominauit Ἑξαπλᾶ, id est sextiplici ordine scripta).31 A similar passage that is even more important for my argument is found in the description of the Hexapla given by Epiphanius in his Panarion. After listing the Greek versions used by Origen, Epiphanius noted that the Alexandrian had included the Hebrew text in Hebrew characters. Then, ‘using a second, parallel column opposite [the first]’ (ἐκ παραλλήλου δὲ ἄντικρυς, δευτέρᾳ σελίδι χρώμενος), he placed the Hebrew words, though ‘in Greek letters’ (δι’ Ἑλληνικῶν δὲ [τῶν] γραμμάτων). The result was that

these [books] were in fact, and were called, Hexapla, since in addition to the [four] Greek translations there were two additional juxtaposed [columns]: Hebrew in the natural manner with Hebrew letters and Hebrew with Greek letters, such that the entire Old Testament was in a sixfold form, being so called due to the two [columns] of Hebrew words

ὡς εἶναι μὲν ταῦτα καὶ καλεῖσθαι Ἑξαπλᾶ, ἐπὶ <δὲ> τὰς Ἑλληνικὰς ἑρμηνείας <γενέσθαι> δύο ὁμοῦ παραθέσεις, Ἑβραϊκῆς ϕύσει δι’ <Ἑβραϊκῶν> στοιχείων καὶ Ἑβραϊκῆς δι’ Ἑλληνικῶν στοιχείων, ὥστε εἶναι τὴν πᾶσαν παλαιὰν διαθήκην δι’ ἑξαπλῶν καλουμένων καὶ διὰ τῶν δύο τῶν Ἑβραϊκῶν ῥημάτων.32

Note first the use of the term παραθέσις (‘juxtaposition’), cognate to the verb παρατίθημι used by Eusebius to describe how Ammonius placed passages from the gospels alongside one another. In addition, the usage of διά here provides the clearest parallel for the function of the preposition in Ammonius’ title. Epiphanius uses it three times with reference to the characters in which the text is written, either ‘with Hebrew letters’ or ‘with Greek letters’. Here the sense of διά alludes to the format or presentation of the text in these columns, a usage in keeping with the third option mentioned above. Then, drawing his summary to a close, he refers to the resulting six-column format of Origen’s work with the phrase δι’ ἑξαπλῶν, a striking parallel to Ammonius’ διὰ τεσσάρων. Additionally, this passage also calls to mind the remainder of Ammonius’ title: τὸ…εὐαγγέλιον. Just as Ammonius put τὸ εὐαγγέλιον in the form of διὰ τεσσάρων, so also Origen put ἡ παλαιὰ διαθήκη in the form of δι’ Ἑξαπλῶν. In both cases, the διά clause refers to the format of the work, while the rest of the title refers to its content.

The most significant difference between the title of Origen and that of Ammonius is that Origen uses the compound form ἑξαπλοῦς (‘sixfold’) from ἕξ + ἁπλόος and cognate to ἐξαπλόω (‘to multiply by six’).33 In contrast, Ammonius’ title uses the simple cardinal form τέσσαρες. Despite this minor difference, the usage of διά plus a number to describe the format of Origen’s work is the most suitable parallel for the sense of the preposition in Ammonius’ title. On this reading, the διά of Ammonius’ title refers not to his four source texts, as one might assume, but rather to the four-column format in which he presented these texts, just as Origen’s title drew attention to the unusual multi-column format of the Hexapla. If this is correct, it makes it difficult to settle on a title in English that adequately captures the sense of the Greek. The closest equivalent might be ‘The Four-Columned Gospel’ or ‘The Gospel in Four Columns’, but perhaps the best way to refer to Ammonius’ composition is simply by transliterating it as we do with the Hexapla, calling it the Diatessaron-Gospel.

There is one further passage, highlighted nearly a century ago by Theodor Zahn, that must also be considered to round out this investigation. In book five of his Commentary on John, Origen, while refuting the Marcionite error, argued that

as he is one whom the many preach, so the gospel recorded by the many is one in its meaning, and there is truly one gospel through the four.

ὡς εἷς ἐστιν ὃν εὐαγγελίζονται πλείονες, οὕτως ἕν ἐστι τῇ δυνάμει τὸ ὑπὸ τῶν πολλῶν εὐαγγέλιον ἀναγεγραμμένον καὶ τὸ ἀληθῶς διὰ τεσσάρων ἕν ἐστιν εὐαγγέλιον.34

Zahn was right to argue that the unusualness of the phrase τὸ διὰ τεσσάρων εὐαγγέλιον makes it unlikely that Origen’s statement here has no relation to the other usages of the phrase in antiquity.35 Nevertheless, the fact that Origen used the phrase in passing, without giving it any sustained attention or attributing it to any other source, makes it difficult to interpret his usage. Zahn supposed that Origen had in mind the so-called ‘Diatessaron’ of Tatian, and that the adverb ἀληθῶς was intended as a polemical contrast with that earlier work. However, given that Origen nowhere else gives any indication of knowing Tatian’s gospel, this seems unlikely.

Another explanation is suggested by the book culture of Origen’s day. When codices containing all four gospels began to be produced, which occurred by the mid-third century at the latest and so within Origen’s lifetime,36 the phrase τὸ διὰ τεσσάρων εὐαγγέλιον would certainly have been a suitable description for such a book, referring to the one gospel that proceeds ‘through’ the four separate, consecutive versions. In this case, the phrase could represent an extension of Ammonius’ usage, and would still be a reference to a distinctive format of a book, although now referring to four successive versions, rather than four simultaneously parallel texts. This, of course, is assuming that Ammonius’ work was prior to or at least contemporary with that of Origen, either of which would be compatible with any of the Ammonii proposed above.

At this point someone will probably object that Tatian’s usage of the same title for his work undermines the preceding argument, since his edition of the gospel contained neither parallel columns nor multiple sequential texts, but simply a single, continuous narrative. However, this objection only applies if Eusebius was correct in calling Tatian’s work the ‘Diatessaron’.37 In fact, I have argued elsewhere, based on the earliest Syriac evidence, that Tatian most likely called his text simply ‘The Gospel’, and that Eusebius is not to be trusted in this instance, especially since he himself implies that he had never seen a copy of Tatian’s edition.38 If so, then the title τὸ διὰ τεσσάρων εὐαγγέλιον quite likely originated with Ammonius and later came to be attached erroneously to Tatian’s very different editorial work, with the influence of Eusebius ensuring that this confusion would become dominant in the later tradition. In fact, it is probably because the title ‘Diatessaron’ has been traditionally associated primarily with Tatian’s work that scholars have not previously considered the possibility that the parallel with the Hexapla might shed light on the meaning of the phrase as it relates to Ammonius’ gospel synopsis.

Alexandrian Scholarly Traditions and Ammonius’ Work

Before leaving Ammonius’ work we should pause to consider what sort of intellectual milieu is implied by the projects of Origen’s Hexapla and Ammonius’ Diatessaron-Gospel. One of the recent advances in the study of Origen’s corpus is the recognition of the importance of classical philology to his intellectual endeavours. The work of Bernhard Neuschäfer was pioneering in this respect and has been followed by many since.39 Neuschäfer drew attention to the fact that it was Alexandrian philology, which had been developed for the study of Homer, that provided the tools necessary for Origen’s creation of the Hexapla. Following the lead of literary critics like Zenodotus and Aristarchus, Origen called his text-critical work an exercise in διόρθωσις, since he, like his predecessors, engaged in the comparative analysis of rival versions in an attempt to establish an authoritative text.40 More recently Anthony Grafton and Megan Williams have emphasized that Origen was not simply appropriating the tools of Hellenistic philology for the church. Rather, he was on the cutting edge of scholarship, since no other classical text existed in as many versions as the Hebrew scriptures, and no other philological undertaking was executed on such a grand scale as his Hexapla. Thus, they conclude that the Hexapla was ‘one of the greatest single monuments of Roman scholarship, and the first serious product of the application to Christian culture of the tools of Greek philology and criticism’.41

Grafton and Williams were no doubt correct to emphasize the unprecedented scale of the project Origen embarked upon, but they failed to note that he may have had at least one significant precursor who carried out a similar project also based in Alexandrian philological scholarship. In a fragment of a letter quoted by Eusebius, Origen justified his own interest in philosophy by pointing to the prior example of Heraclas, bishop of Alexandria, whom he found ‘with the teacher of philosophical studies’ (παρὰ τῷ διδασκάλῳ τῶν ϕιλοσόϕων μαθημάτων). Because Eusebius picks up in mid-letter, Origen does not state who this philosopher was, but his citation of this passage occurs in the context of his discussion of Porphyry’s statement about Origen studying with Ammonius. For this reason, Mark Edwards is surely right that Eusebius intends the reader to assume that the unnamed master with whom bishop Heraclas studied was the same Ammonius mentioned by Porphyry as also the teacher of Origen. In other words, he was the Ammonius who probably produced the Diatessaron-Gospel.42

The importance of this passage for my argument is that Origen goes on to say that, by studying with this philosopher, Heraclas ‘was constantly engaged in the philological criticism of the books of the Greeks, so far as he was able’ (βιβλία τε Ἑλλήνων κατὰ δύναμιν οὐ παύεται ϕιλολογῶν).43 Similarly, if we accept Edwards’ argument that Origen’s teacher Ammonius was the Peripatetic Ammonius, it is striking that Longinus singled out this Ammonius precisely for his philological learning, calling him, along with a certain Ptolemy, ‘the most erudite (ϕιλολογώτατος) men of their epoch, Ammonius in particular, whose broad learning (πολυμαθίαν) was without parallel’.44 The sense of the term ϕιλόλογος in this context can be illuminated by considering Plotinus’ disparaging assessment of Longinus himself as someone who was ‘a philologist but certainly no philosopher’ (ϕιλόλογος…ϕιλόσοϕος δὲ οὐδαμῶς).45 The rationale behind Plotinus’ judgement becomes clear in the light of the list of Longinus’ works in the Suda, including ‘Difficulties in Homer, Whether Homer is a Philosopher, Homeric Problems and Solutions in Two Books, Things Contrary to History that the Grammarians Explain as Historical, On Words in Homer with Multiple Senses in Four Books, two publications on Attic diction arranged alphabetically, [and] the Lexicon of Antimachus and Heracleon’.46 These are clearly works of a more philological bent which draw on the Aristarchan tradition of Homeric criticism emnating from Alexandria, and as such they explain what Plotinus had in mind when he called Longinus a ϕιλόλογος and, by extension, what Longinus himself meant when he referred to Ammonius as ϕιλολογώτατος.

If this Ammonius was Origen’s tutor, as seems likely, then Origen’s application of Alexandrian literary scholarship to Christian sources was not completely unprecedented. Rather, Ammonius had already pioneered this approach, which his more famous pupil later deployed on a grander scale.47 Scholarly concerns about the internal unity and coherence of a text had emerged in the third and second centuries bce in the work of Zenodotus and Aristarchus on Homer, and Alexandrian Jewish scholars adopted their methods for the purpose of dealing with apparent contradictions in the Septuagint.48 The projects of Ammonius and Origen were no doubt motivated at some level by a similar concern to avoid textual dissonance, though the scale of the problems they attempted to address was unparalleled. Just as the Hebrew scriptures existed in more editions than any other ancient text, and so required the development of new methods to handle this textual plurality, so also the fourfold gospel, consisting of four irreducibly distinct yet similar texts in a single corpus, was a situation without exact parallel in classical or Jewish sources, and it is therefore not surprising that it too elicited a cutting-edge response from the scholars of Alexandria.49

The two most significant points of similarity in the projects of Ammonius and Origen are: first, the fact that both engaged in what was at root a comparative analysis of texts—for Ammonius comparison of variations on a single life story and for Origen comparison of multiple translations of the same text—and, secondly, that both recognized that parallel columns could greatly facilitate such comparative analysis. Recently Eleanor Dickey has drawn attention to a genre of ancient school texts that used parallel columns to show the translation of terms between Latin and Greek, and Andrew Riggsby has argued persuasively that this genre of literature must have informed Origen’s Hexapla.50 Yet the use of parallel columns in this manner is otherwise very rarely attested in this period, and it can hardly be a coincidence that two Christian authors, both in Alexandria around the same time, realized that this pedagogical tool could be used on a much vaster scale as a powerful methodology for a scholarly research project. Ammonius and Origen, in other words, must have come from the same intellectual culture in which the methods of Alexandrian philological criticism were finding fresh vitality through their application to new corpora of texts.51

Hence, although Grafton and Williams may be correct that the Hexapla ‘spawned a range of imitations and adaptations intended for a variety of uses’ and that later Christian authors ‘attributed the whole tradition [of multicolumn Bibles] to Origen as its intellectual father’52, Origen in fact probably drew the inspiration for his work from the earlier literary scholarship of Ammonius who had already pioneered this format as a convenient way to analyse the relationships among the four gospels. It is therefore unfortunate that, while Origen is regularly and rightly lauded for his monumental contribution to Old Testament textual criticism with his Hexapla, Ammonius is not typically accorded the same respect when it comes to scholarship on the gospels. In fact an appreciation of the complexity of the similarities and differences amongst the gospels did not first emerge in the eighteenth-century. Rather, educated Christians became aware of this issue perhaps not more than a century after the last evangelist put down his pen, and the attempt to use state-of-the-art scholarly tools to better understand the problem is to be traced back to the Christian appropriation of philological scholarship in late-antique Alexandria.

Eusebius’ Continuation of Ammonius’ Scholarly Project

Tabular Methods in Eusebius’ Broader Corpus

Let us now consider how this early tradition of scholarship on the fourfold gospel, which began in the second or third century in Alexandria, was carried forward a century later by Eusebius in Caesarea. Despite the rarity of tables in the ancient world, the Canon Tables were not Eusebius’ only experimentation with this technology. Examining his other uses of tabular methods will situate his adaptation of Ammonius’ Diatessaron-Gospel within his broader corpus. This is an aspect of his work that has been explored most recently by Grafton and Williams, who aptly describe the Caesarean bishop as ‘a Christian impresario of the codex’,53 thereby highlighting the fact that Eusebius’ innovations in information technology exploited the increasingly dominant late antique book form which was well on its way to replacing the traditional bookroll by the early fourth century. Scholars have long recognized that Christians in general adopted the codex earlier and more consistently than their non-Christian peers, particularly for sacared, liturgical texts,54 so by Eusebius’ time there was a long-standing Christian preference for the codex over the bookroll. Eusebius, however, more than any other figure in late antiquity, seems to have recognized and exploited the possibilities afforded by the new book form.55 In the previous chapter I highlighted the fact that most of the surviving papyrus fragments of Ptolemy’s Handy Tables came from codices, and suggested that this format was most likely employed because it better facilitated the back-and-forth kind of reading required to use the book for calculations, a mode of interaction similar to that envisioned by the Canon Tables. As Jason König and Tim Whitmarsh have observed, ‘It is surely no coincidence that the earliest codices contained Christian and technical material, two genres of discourse that privilege, indeed insist upon, cross-referencing and non-linear reading’.56It is worth emphasizing this point again here because the other Eusebian works to be discussed below encourage a similar kind of usage and so also are particularly suited to the codex format.

At least two of Eusebius’ other works contained lists or tables that he described as κανόνες, in keeping with his usage of this term in the Letter to Carpianus. The most wide-ranging of these was his Chronicle, an ambitious attempt to condense Babylonian, Egyptian, Jewish, Greek, and Roman chronography into a single, coordinated timeline of world history. The first half of this two-part work consisted of a discussion of the sources and problems attendant on such an enterprise, and the second half, bearing the title Χρονικοὶ Κανόνες, boldly combined these sources into a unified tabular format allowing cross-referencing between various national histories.57 His Chronicle was not entirely original, but rather borrowed ‘the content, structure, style, and historical approach of the Hellenistic chronicle’, a genre of literature that typically reported important events for a given city or kingdom which were arranged chronologically and dated according to Olympiads.58 Eusebius, however, transformed this existing genre in two ways.59 The first was the scope of his ambition. He recorded a total of fifteen distinct national chronologies,60 which would have presented a bewildering array of competing dating systems, yet he managed to synchronize them all by situating the chronologies with reference to the birth of Abraham as a universal starting point and marking intervals of time subsequent to this point by the tabular rows that followed. The second innovation was his creative use of parallel columns to display this potentially overwhelming amount of information. Each vertical column in the Χρονικοὶ Κανόνες represents a single kingdom, so the number of columns varies depending on how many kingdoms were in existence at any given time. At most this meant that nine parallel columns had to be presented at once across a two-page spread, a complex format that represents an impressive achievement in terms of information visualization.61

This arrangement of information resulted in the creation of a table in the strict sense of the term (as discussed in the previous chapter), one that allowed the user to navigate either vertically or horizontally in open-ended exploration of the information contained therein. By reading vertically one could follow the individual history of a given kingdom diachronically, or by reading horizontally one could see what events were occurring simultaneously at any given point in time. This presentation of information across two axes was apparently without precedent in the prior tradition of Olympiad chronicles,62 and Eusebius himself highlighted the utility of such a format:

And, lest the long series of numbers should lead to some sort of confusion, we have divided the whole accumulation of years into decades, which we gathered together from the individual histories of the nations and placed in turn opposite one another. The purpose of this was to provide a simple method of finding out (facilis praebeatur inuentio) at which time—whether Greek or barbarian—the prophets, kings, and priests of the Hebrews existed; likewise the time at which the gods of the various nations were falsely believed in, along with heroes; the time at which a city was founded; with respect to illustrious persons, when philosophers, poets, princes, and writers of various works arose; and any other ancient occurrences that were thought to be worth remembering. All of this we will put in its proper place with the greatest brevity.63

This passage is one of the clearest statements we have demonstrating Eusebius’ awareness of the impact of formal design on the use of a text. The goal he envisions is to be able to find what one is looking for with ease, and he recognizes that the best way to accomplish that goal is with a presentation that is as concise and clear as possible—the juxtaposition of diverse material in discrete, parallel columns synchronized by rows that mark off regular intervals.

Hence, although the discipline of chronography was centuries old by the time Eusebius tried his hand at it,64 his approach was innovative in the way in which it arranged the complex material he drew from his sources for the purpose of comparative analysis. This, of course, was precisely the aim of the mis-en-page of Origen’s Hexapla, and, given this similarity and Eusebius’ familiarity with the Hexapla, it seems undeniable that Eusebius’ innovation with the Chronicle was inspired by that earlier endeavor.65 Nevertheless, the application of this technique to historical materials ‘represented a dramatic formal innovation’, which resulted in ‘a stunningly original work of scholarship’66. Moreover, the transfer of this technology from the realm of textual scholarship, as it was used in the Hexapla, to the domain of chronological historiography is another remarkable sign of Eusebius’ ingenuity, given the paucity of such crossovers in the Greco-Roman world.

Before leaving the Chronicle I want to examine one further passage in which Eusebius comments on the relation between it and his better-known Ecclesiastical History. At the outset of the Ecclesiastical History he explains how he has gone about writing the present work, what its aim is, and its significance as the first work of its kind. After expounding on such matters, he then comments,

Previously I have already made a summary of these things in the chronological tables that I formed, but, however, in the present work I have undertaken to present the most complete narrative of these same matters.67

ἤδη μὲν οὖν τούτων καὶ πρότερον ἐν οἷς διετυπωσάμην χρονικοῖς κανόσιν ἐπιτομὴν κατεστησάμην, πληρεστάτην δ’ οὖν ὅμως αὐτῶν ἐπὶ τοῦ παρόντος ὡρμήθην τὴν ἀϕήγησιν ποιήσασθαι.

Clearly this means that Eusebius wrote this passage of the Ecclesiastical History after he had finished book two of the Chronicle, containing his chronological canons. More importantly, the latter work served as a ‘summary’ of the narrative account extended over multiple books in the Ecclesiastical History. Indeed, the information contained in the latter portion of the chronological tables, especially the succession lists of bishops and the notices of the key events pertaining to important figures in the history of the church, would have served as an ideal skeletal framework upon which to construct a proper historical narrative.68 The reason for drawing attention to this passage here is that it serves as a fitting inverse analogy for the way in which the Canon Tables relate to the text of the gospels. What this passage establishes is that in Eusebius’ mind a tabular matrix was a condensed summary of information that could be expanded upon in a different genre of writing. If so, then just as the chronological canons were an ἐπιτομή of the extended ἀϕήγησις in the Ecclesiastical History, so also by implication the Canon Tables were an ἐπιτομή of the four ἀϕηγήσεις of the gospels.

The second Eusebian work that shows a similar experimentation with information visualization was much more restricted in scope and simpler in function, and was also less successful, surviving in only a single manuscript (Oxford, Bodleian Library, Auct. D.4.1, fol. 24v‒25r). In a recent publication Martin Wallraff has called this work the ‘Canon Tables of the Psalms’, though the title in the tenth-century Greek manuscript is rather different: Πίναξ ἐκτεθεὶς ὑπὸ Εὐσεβείου τοῦ Παμϕίλου.69 Πίναξ does not have precisely the same semantic range as κανών and seems to refer to a ‘list’ in contrast to κανών in the sense of a tabular matrix, as used by Ptolemy. For example, in his Ecclesiastical History, Eusebius at one point mentions the πίνακες drawn up by Pamphilus for the library in Caesarea, referring to the catalogues of authors and works contained therein.70 This sense of the word goes back at least to Callimachus (c.305–c.240 bce), who titled his 120-book catalogue of Greek authors and works in the Alexandrian library the Πίνακες.71 Since the Eusebian work in question is a list of texts arranged according to authorship, the word Pinax is an apt title, in keeping with the Callimachan tradition and the work of Pamphilus and Eusebius in cataloguing the Caesarean library. The usage of this term may also be related to the fact that this Pinax is not a true tabular matrix with vertical columns and horizontal rows, but a more simple collection of vertical lists. However, in the sole surviving copy each of these lists is called a κανών, so perhaps the sense of the two terms overlapped in Eusebius’ understanding.

As suggested by Wallraff’s title, this work was focused on the psalter and was an attempt to classify the one hundred and fifty psalms contained in it according to authorship. Eusebius accomplished this by producing seven κανόνες, each of which listed the psalms attributed to a given author: psalms of David, psalms of Solomon, unlabelled psalms, psalms of the sons of Korah, psalms of Asaph, anonymous psalms, and Hallelujah psalms, with two further categories containing only a single psalm each, attributed to Ethan and Moses. Because each of these categories of material is in no way cross-referenced with any other, there is no need to read horizontally across the κανόνες. Rather, one simply uses the list to identify all of the psalms that belong to a given category, which can then be explored in whatever order one would like. Though less complex than the Canon Tables for the gospels, this work presents at least two parallels to Eusebius’ more successful paratext. The first is that the Pinax for the Psalms is an attempt at providing a reader with an improved navigation of a text through the classification of portions of that text into discrete categories, precisely the same goal and method as the Canon Tables apply to the gospels. The second is that, in the sole surviving copy of the Pinax, the κανόνες are housed within architectural frames, which, if original, lend support to the hypothesis that the architectural frames usually found in copies of the Canon Tables for the gospels likewise go back to Eusebius.72

We do not know when Eusebius created his Canon Tables for the gospels, so it is impossible to situate them in a developmental chronology with these other two works.73 Nevertheless, all three speak to a common attempt to present complex information in a visual form for the purpose of rendering it more accessible. We might then say that Eusebius was the Steve Jobs of the codex, someone who realized the power of design for shaping a user’s interaction with content. More specifically, the Canon Tables for the gospels overlap with each of these other projects in different ways.74 Like the Pinax for the Psalms, the Canon Tables provided a classificatory scheme for a body of textual material in order to structure the user’s experience of the text, making it easier to navigate. And like the Chronological Tables, the Canon Tables required the coordination of multiple data sets, each of which had their own internal logic, which could not simply be discarded but rather had to be synchronized according to some all-encompassing, external system of demarcation. For the Chronological Tables this was managed by placing each national chronography in relation to the number of years from Abraham, while for the Canon Tables it was accomplished by the numeric matrices, which acted as an external reference system that left the text of each of the gospels intact.75 Hence, if the Chronicle and the Pinax for the Psalms predate the Canon Tables, then they provided Eusebius with the experimental expertise required for producing the latter work. However, even if not, these two works demonstrate those aspects of Eusebius’ ingenuity that he would bring to bear in order to improve upon Ammonius’ prior scholarly investigations.

What did Eusebius Take from Ammonius?

With this background in place, it is now time to return to the Letter to Carpianus to continue analysing Eusebius’ comments on Ammonius’ Diatessaron-Gospel. Though, as noted above, he praises Ammonius’ industriousness and acknowledges his own debt to him, Eusebius also highlights the fundamental insufficiency of his predecessor’s work. Ammonius’ method of arranging the parallel material from the latter three gospels alongside Matthew had

the unavoidable result that the continuous thread of the other three was destroyed, as far as a text for reading is concerned

ὡς ἐξ ἀνάγκης συμβῆναι τὸν τῆς ἀκολουθίας εἱρμὸν τῶν τριῶν διαϕθαρῆναι ὅσον ἐπὶ τῷ ὕϕει τῆς ἀναγνώσεως.76

Though Ammonius’ Ditaessaron-Gospel usefully places similar passages alongside one another so that they can be compared, it makes it impossible to read anything other than Matthew in its proper sequence. This serious limitation meant that the Diatessaron-Gospel could never rise beyond the category of an innovative scholarly reference tool, epiphenomenal to the gospelbook itself, as indeed is the case today with modern gospel synopses.77 Recognizing this problem, Eusebius presents a twofold purpose for his composition. He intends to achieve the same fundamental goal as Ammonius—showing parallel material between the gospels—but to do so ‘while preserving the body and sequence of the other [gospels] throughout’ (σωζομένου καὶ τοῦ τῶν λοιπῶν δι’ ὅλου σώματός τε καὶ εἱρμοῦ). His criticism of Ammonius is, therefore, carefully measured. He does not wholly reject his predecessor’s work, and his earlier praise for the Alexandrian’s labour should be taken as sincere. Nevertheless, he recognizes an inevitable limitation in Ammonius’ procedure, and hopes to improve on this earlier composition by using a ‘different method’ (καθ’ ἑτέραν μέθοδον).

About the format of Ammonius’ work there is widespread agreement. However, the exact relation between Eusebius’ Canon Tables and Ammonius’ Diatessaron-Gospel is not uncontested territory. Although the sections and numbers in Eusebius’ system have often been called by the adjective ‘Ammonian’,78 there exists a significant contrary trend that maintains that these are the sole creation of Eusebius himself. This position was stated emphatically in 1871 by John W. Burgon, who, as a part of his rather heated defense of the longer ending of Mark, described it as a ‘vulgar error’ to ‘designate the Eusebian Sections as the “Sections of Ammonius”’.79 Burgon’s arguments to this end were, 1) that Eusebius’ Canon Tables were designed to show non-Matthean parallels among Mark, John, and Luke, and to show material distinct to the latter three, whereas such was impossible on Ammonius’ system; and 2) the Canons and the sections ‘mutually imply one another’ such that one without the other would be useless.80 Hence Eusebius must have created them both. In 1881 Theodor Zahn made the same point, though for different reasons, and nearly forty years later Zahn was still trying to convince the scholarly guild of its error in this respect.81 In the early twentieth century Eberhard Nestle, expressly following Burgon, similarly said one should never speak of the ‘Ammonian sections’, since the section division was entirely the work of Eusebius.82 More recently Timothy Barnes has concluded that the term ‘Ammonian Sections’ ‘does Eusebius a grave injustice, for the division of the Gospels into numbered sections is his idea’.83 These arguments are rightly aimed at giving Eusebius due credit for his invention. Nevertheless, I want to suggest that these scholars have gone too far in claiming that the two works had nothing whatsoever in common.

Rightly articulating the relationship between the contributions of these two figures centres around the interpretation of a key word in Eusebius’ letter. As he transitions to describing his own creation, Eusebius notes that ‘he took (his) starting points from the labour of the aforementioned [Ammonius]’ (ἐκ τοῦ πονήματος τοῦ προειρημένου ἀνδρὸς εἰληϕὼς ἀϕορμάς).84 What exactly did Eusebius take from Ammonius? Barnes translates ἀϕορμάς as ‘point of departure’, Burgon as ‘hint’ or ‘suggestion’, and Zahn as ‘Anregung’.85 For the term LSJ lists ‘occasion’ or ‘pretext’ as well as ‘means with which one begins’ or ‘resources’. In keeping with the latter sense, the word can take on the economic meaning ‘capital’ or the rhetorical meaning ‘food for argument, material, subject’.86 So the semantic range is broad enough to encompass the more generic causal sense of ‘occasion’ or ‘impetus’, as well as a more specific sense indicating a greater degree of material continuity between the ἀϕορμή and the resulting piece of work.

The latter sense, I want to argue, is what Eusebius had in mind, especially in view of the fact that he uses the term in the plural. According to Thesaurus Linguae Graecae, the word occurs some thirty-three times in his corpus, in both the singular and plural forms. When it is used in the singular, it usually means something more general like ‘occasion’ or ‘pretext’. For example, Eusebius quotes Melito of Sardis stating that certain persons were persecuting the Christians by taking their ‘occasion’ from the imperial edicts. In another passage the church historian reports that he is unable to give more precise information about a number of figures because he does not have the ‘occasion’ to do so. In another instance Eusebius passes on a report that Satan entered into the schismatic Novatus, becoming the ‘occasion’ for his unbelief.87

However, when it is used in the plural, the term often implies that the ἀϕορμαί bear some more material relation to that which results from them. For example, Eusebius quotes the report of Irenaeus that the heretic Cerdon took his ‘material’ (ἀϕορμάς) from those who followed Simon Magus. Later on the historian asserts that by studying the scriptures from his childhood Origen had stored up ‘no small amount of resources (ἀϕορμάς) of the words of the faith’.88 In addition to these two occurrences in the plural in the Ecclesiastical History, there are also over a dozen plural usages in Eusebius’ Praeparatio Evangelica. For example, he cites Philo of Byblos stating that Pherecydes, ‘taking his starting points from the Phoenicians, theologized about the god he called Ophion’ (παρὰ Φοινίκων δὲ καὶ Φερεκύδης λαβὼν τὰς ἀϕορμὰς ἐθεολόγησεν περὶ τοῦ παρ’ αὐτῷ λεγομένου Ὀϕίονος θεοῦ). Just a little further on, in the same extract, Philo of Byblos wrote that ‘everyone, taking their starting points from Tauthus, discoursed on the natural principles’ (πάντες δὲ τὰς ἀϕορμὰς παρὰ τοῦ Τααύτου λαβόντες ἐϕυσιολόγησαν). Aristobulus, quoted by Eusebius in the eighth book of the treatise, explained that certain ‘philosophers and many others, even poets, took great material from [Moses]’ (ϕιλόσοϕοι καὶ πλείονες ἕτεροι καὶ ποιηταὶ παρ’ αὐτοῦ μεγάλας ἀϕορμὰς εἰληϕότες). Later, Eusebius quotes Clement of Alexandria, who claimed that Genesis 1:1 ‘presented to the [Greeks] the starting points of a material substance’ (ἡ λέξις ἡ προϕητικὴ ἐκείνη· ‘Ἡ δὲ γῆ ἦν ἀόρατος καὶ ἀκατασκεύαστος’ ἀϕορμὰς αὐτοῖς ὑλικῆς οὐσίας παρέσχηται), and that the Orphic word μητροπάτωρ ‘gave to those who introduce emissions the means to think that God has a consort’ (ἐνδέδωκε δὲ ἀϕορμὰς τοῖς τὰς προβολὰς εἰσάγουσι τάχα καὶ σύζυγον νοῆσαι τοῦ θεοῦ). Finally, in book fourteen Eusebius himself asserts that Epicurus ‘took the material from [the Cyrenaic sect] for the exposition of [humanity’s] end’ (ἀϕ’ ἧς τὰς ἀϕορμὰς Ἐπίκουρος πρὸς τὴν τοῦ τέλους ἔκθεσιν εἴληϕεν) and that a certain saying of Metrodorus ‘gave evil material to Pyrrho who came afterwards’ (κακὰς ἔδωκεν ἀϕορμὰς τῷ μετὰ ταῦτα γενομένῳ Πύρρωνι).89

This series of examples is sufficient to indicate that when Eusebius says that one individual ‘took’ or ‘gave’ ἀϕορμάς to or from someone else, he intends to establish an intellectual genealogy between the two, implying a significant degree of continuity between them. This is not a uniquely Eusebian usage. A particularly clear passage on this point is found in the summary of the views of the grammarians provided by the sceptic Sextus Empiricus: ‘That poetry provides numerous starting points (ἀϕορμάς) toward happiness is clear from the fact that the most truly powerful and character-building philosophy was rooted at the beginning in the gnomic utterances of the poets, and for this reason if philosophers say something by way of exhortation they seal it, so to speak, with poetic sayings’.90 Note that the justification for seeing philosophical ‘starting points’ in the poets is that philosophy from the beginning ‘was rooted’ in poetry. Like Eusebius, Sextus Empiricus assumes that ἀϕορμαί are what one takes from someone else as a kind of raw material, to which one then applies some kind of process for the purpose of formulating one’s own contribution to the issue at hand. The final product will not be identical to that with which one began, but it is materially indebted to it. In the light of this background, when in the Letter to Carpianus Eusebius stated that he had ‘taken’ ἀϕορμάς from Ammonius, he was claiming precisely such an intellectual pedigree. It was not merely the deficiencies of Ammonius’ creation or the general idea of comparing gospel passages that inspired his labour. Rather, the Diatessaron-Gospel provided for him the ‘starting points’ or perhaps ‘raw material’ that he reworked according to a different method for his own composition. Therefore, in the light of Eusebius’ usage of ἀϕορμή, those scholars who have argued there is no real relation between the Diatessaron-Gospel and the Canon Tables are mistaken, since Eusebius himself indicates that there is a significant continuity between the two works.

Eusebius’ Modus Operandi

We can state more precisely what this continuity was by speculating for a moment about how Eusebius might have gone about his work.91 Ammonius had essentially already demarcated the Gospel of Matthew into sections, simply based on where he ended one parallel and began another. Similarly, his method had the same effect for the other three gospels, at least for those passages with Matthean parallels, since he had to decide which chunks of these gospels to use as parallels for Matthew in a cut-and-paste method. In other words, what Ammonius had already accomplished was establishing a set of parallels with Matthew, consisting of sets of discrete passages of text, and these parallels could easily have been taken over by Eusebius into his new system. In fact, given that he clearly had access to Ammonius’ work and surely realized how much easier it would have made his own task, the burden of proof should rest on those who want to maintain that he did not incorporate his predecessors’ parallels into his new apparatus. It follows, then, that the parallel passages noted in these Canons likely, in some form, go back to Ammonius, though we cannot exclude the possibility that Eusebius tweaked them here and there to his own liking.92 As a result, it is best to avoid talk of the ‘Ammonian sections’, though when we speak of the ‘Eusebian sections’ we should always bear in mind his indebtedness to his Alexandrian forebear.

The data constituted by these parallels provided the ‘starting points’ for Eusebius’ labour. To rework them according to his own method, he would only have had to follow five steps.93 First, as he looked through the Diatessaron-Gospel he could easily have discovered that there were eight possible combinations of passages that appeared: (1) Mt-Mk-Lk-Jn, (2) Mt-Mk-Lk, (3) Mt-Lk-Jn, (4) Mt-Mk-Jn, (5) Mt-Lk, (6) Mt-Mk, (7) Mt-Jn, and (8) material distinctive to Matthew without any parallel. Eusebius probably took over these eight combinations, making them Canons I–VII and Canon XMt in his system. This specific point was already recognized in the ninth century by the Irish scholar Sedulius Scottus, whom we will meet again in chapter six.94 In other words, Eusebius first used Ammonius to establish the categories of relationship among the gospels simply by analysing the parallels included in the Diatessaron-Gospel.

Eusebius’ second step would have been to make marginal notations in an unmarked copy of Matthew to demarcate the text into sections based on the established parallels and then to enumerate these sections. Eusebius never tells us that Ammonius numbered the sections in his synopsis, and the functioning of his composition did not require enumeration, so we should infer that the numbers are Eusebius’ contribution, and we should accordingly speak of the ‘Eusebian numbers’.

Thirdly, Eusebius had to demarcate Mark, Luke, and John into sections. Here again Ammonius had already contributed some of the work, since Eusebius could have worked through Ammonius’ parallels with Matthew and use them to mark the parallels in the margin of the text of the latter three gospels. This, however, would have been a more difficult task than sectioning Matthew, since these parallels would have been included in Ammonius’ scheme according to Matthew’s narrative order, not according to the sequence of the other three, and so would have required much turning of pages to find the correct passages in the latter three gospels. Moreover, if Ammonius had not included non-Matthean parallels in his work, Eusebius would then have had to work through the remaining text from these three gospels that was not yet sectioned in order to establish his own parallels among this remaining material. At this point he could have used any of the three as a plumbline to check for parallels. His apparent choice was to use Luke, most likely because Luke, being the longest of the remaining three, offered the potential for the most parallels with the other two.95 Working back through Luke’s gospel, looking for material similar to Mark and John, Eusebius must have further subdivided these three gospels, noting down the parallels for his Canons VIII (Lk–Mk) and IX (Lk–Jn).

Eusebius’ fourth step would have been to enumerate the sections he had created in Mark, Luke, and John, and his fifth and final step was to collate into tables the section numbers according to the relational categories he had established. This entire process was intricate and complex, so the fact that the resulting system is almost entirely free of errors is a remarkable scholarly achievement.96 One of the small errors that does show up in the system is that on a handful of occasions a new section is started where it is not needed.97 Recall that according to the logic of the Canons, a new section should only begin when the text transitions to a passage with a different relationship to other gospel passage(s). In theory this should mean that there will never be consecutive sections which are attributed to Canon X, since Canon X passages have no parallels in the other gospels, and in fact consecutive Canon X passages almost never occur, though there are a few exceptions. Luke 6:24–25 and 6:26 (Lk §50, 51) are both ascribed to Canon X, as is Luke 7:11–16 and 7:17 (Lk §67, 68), Luke 9:61–2 and 10:1 (LK §106, 107), Luke 13:1–5 and 13:6–13 (Lk §163, 164), and John 7:33 and 7:34–49 (Jn §80, 81). In each of these instances, the two consecutive passages should have been treated as one section and enumerated accordingly.

Whence then did these errors arise? Ammonius’ work had already included all of Matthew, noting parallel and unique passages from beginning to end. However, if Ammonius had not included the content from the latter three gospels that does not have Matthean parallels, Eusebius would have had to undertake original research with Mark, Luke, and John. Among these three Mark, as the shortest, had the least amount of remaining text to be placed in an appropriate Canon. Hence, Eusebius probably had to do the largest amount of original work with the remaining portions of Luke and John that were omitted from Ammonius’ edition, so it is sensible that these are the places where errors would most likely occur. Probably what has happened is that Eusebius divided each of these passages into two sections because he intended to place them in different Canons, but later either forgot to do so or realized that the parallels he had in mind were not close enough to warrant juxtaposition. Hence these passages were simply relegated to Canon X as distinctive material to each of these gospels. These are errors that could have been removed by recombining the unnecessary doublets and renumbering the subsequent sections, but for whatever reason, Eusebius chose not to do this. At any rate, they are at least errors that do not hinder the goal of the overall system to provide cross-references between gospels.

In conclusion, then, we can say that the majority of the parallels, at least those for Canons I–VII and one quarter of Canon X, go back in some form to the work of Ammonius. However, the enumerating of the sections and the collating of their numbers were the work of Eusebius. Therefore, the resulting composition was truly the product of the labour of both scholars, with Eusebius appropriating and improving upon his predecessor’s work. Accordingly, the opening page of the sixth-century Rabbula Gospels, which presents a combined portrait of Ammonius and Eusebius, is indeed a fitting tribute to the work of the two men (see figs 19–20).98

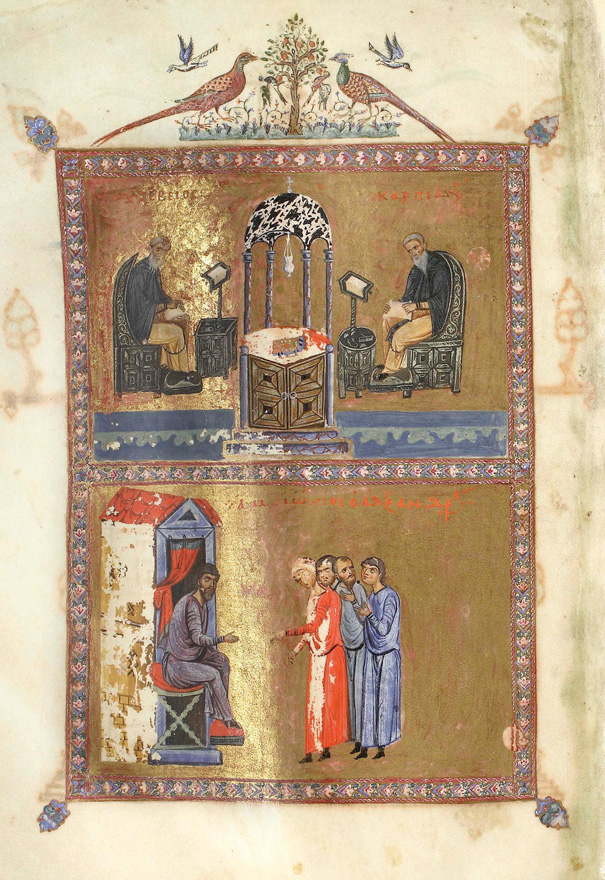

Fig. 19. Portraits of Ammonius (right) and Eusebius (left) in the Rabbula Gospels (sixth c.).

Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, MS. Plut. 1.56, fol. 2r

Fig. 20. Image of Eusebius (top left), Carpianus (top right), and Ammonius (bottom) in Parma, Biblioteca Palatina, MS. gr. 5, fol. 12v (latter half of eleventh c.).

By permission of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism

I argued in the last chapter that the design of Eusebius’ Canon Tables is indebted to astronomical tables such as those produced by Ptolemy, or perhaps by Christian paschal tables that had drawn upon that earlier astronomical genre. The present argument for his indebtedness to Ammonius is not meant to undermine that earlier claim. It remains the case that as a purely numerical matrix, Ptolemy’s Handy Tables presents by far the closest ancient analogy to the Canon Tables, and this formal similarity seems hardly coincidental. However, it is also possible that the mis-en-page of Eusebius’ Canon Tables was partially inspired by Ammonius’ composition. The columnar format of the Canon Tables could have been simply carried over directly from the design layout of the Diatessaron-Gospel, with Eusebius retaining a discrete column devoted to each gospel and the usage of rows to juxtapose parallel passages.99 In other words, all Eusebius had to contribute to the mis-en-page of Ammonius was the replacement of sections of text with numbers. This, in fact, is the fundamental conceptual breakthrough that enabled him to advance beyond the work of his predecessor—the realization that passages of text could be symbolically represented by numbers. As reviewed in the last chapter, by Eusebius’ time authors regularly divided lengthier works up into numbered books, as Eusebius himself did with his other works. Moreover, as pointed out by Martin Wallraff, this insight is also evident in the Pinax for the Psalms, in which the various psalms are referred to by their numbers.100 Hence, Eusebius’ usage of this method in the Canon Tables was not wholly original, but it is nevertheless the case that no one, either Christian or non-Christian, had ever exploited this insight to such a degree.101

It was, therefore, from the confluence of all of these factors that the Canon Tables emerged: in the Chronicle Eusebius had devised an all-encompassing reference scheme that left intact the distinct internal logic of the data sets he was combining; in the Pinax for the Psalms he had experimented with referring to texts by numbers and categorizing constituent parts of a literary corpus; and in Ammonius he had a predecessor who had inaugurated the study of gospel parallels by using a columnar format. Perhaps all it took was Eusebius seeing something like a Ptolemaic table for him to realize that numbers in a matrix could be used as an external reference scheme for the fourfold gospel, one that, unlike Ammonius’ Diatessaron-Gospel, preserved the structure of the gospel narratives.

The result of this innovation was that a codex with Canon Tables began with a symbolic summary of the fourfold gospel before one even arrived at the start of the actual text. In an age accustomed to scholarly tools such as footnotes, indexes, and cross-references, it is difficult for us to imagine how startlingly innovative the Canon Tables must have appeared to a late-antique reader. For probably the first time in intellectual history, a problem of textual complexity was rendered in numerical form. Yet despite its innovative quality, Eusebius’ creation proved to be incredibly popular, owing in part to one significant advantage it had over Ammonius’ earlier work. While the Diatessaron-Gospel could never have been more than a secondary reference tool, Eusebius found a way to accomplish the same goal while leaving the text of each gospel intact, thereby allowing for his new system to be included in liturgical codices and widely disseminated. The implication of this advance should not be missed. Eusebius contributed significantly to the developing Christian traditions of late antiquity and the early medieval period by making the elite philological scholarship of Alexandria available on a scale few could ever have imagined. The present argument therefore stands in agreement with the recent assessment of Michael J. Hollerich that Eusebius was ‘a true founder of Christian biblical scholarship’.102

From Formlessness to Polymorphic Diversity

Yet Eusebius’ creation was not merely a scholarly tool in the modern sense of the genre. It was also laden with a symbolic, even mystical significance that may not be immediately obvious to the modern reader. Eusebius’ tendency to use a visual medium to make a theological statement has been emphasized recently by Grafton and Williams in their study of his experimentations with the opportunities afforded by the new technology of the codex. They drew attention to the way in which the Chronicle began with tables of parallel monarchies, but, as the reader progressed through history, all others fell away to leave only the list of Roman rulers. As a kind of ‘dynamic hieroglyph’, this display of textual material communicated Eusebius’ conviction that ‘world history culminated in the contemporary Roman Empire’.103

Scholars have long speculated about a similar impulse evident in the Canon Tables. Nordenfalk pointed out that the ten Canons do not exhaust all of the possible combinations presented by the fourfold gospel, since the parallels Mk–Lk–Jn as well as Mk–Jn are absent.104 Eusebius’ omission of these categories is, however, more likely due to the small amount of content for these Canons, since there is little material shared by Mark, Luke, and John that is not also shared by Matthew, and even less non-Matthean content that is contained jointly in Mark and John but not in Luke. A more compelling observation related to the number ten is that Eusebius did not assign the distinctive material for each gospel to a separate Canon, as his prior method with Canons I–IX would imply, but instead grouped all four distinct categories together into a single table, Canon X. This clear departure from his pattern with the first nine categories suggests a desire to preserve the number ten, as though the number of the Canons was intrinsic to the overall message communicated by the tables. The number ten seems also to have been a factor in the page-layout of the tables. Nordenfalk attempted to reconstruct the Eusebian archetype from the surviving late-antique and early medieval models, and, after examining a number of later examples, he concluded that the tables were originally distributed over five folia, comprising ten pages.105

Nordenfalk plausibly suggested that this highlighting of the number ten is due to a Pythagorean recognition of the relation of the numbers four and ten, specifically the fact that ten is the sum of the numbers from one to four.106 An example of this tradition probably contemporary with Eusebius is the ps-Iamblichan treatise The Theology of Arithmetic, which offers a commentary on each of the first ten numbers. About the number ten the text notes ‘a natural equilibrium and commensurability and wholeness existed above all in the decad’.107 Earlier in the treatise, the author opens the discussion of the tetrad by commenting, ‘Everything in the universe turns out to be completed in the natural progression up to the tetrad, in general and in particular, as does everything numerical—in short, everything whatever its nature. The fact that the decad…is consummated by the tetrad along with the numbers which precede it, is special and particularly important for the harmony which completion brings’.108 As noted by Nordenfalk, Eusebius himself highlighted this Pythagorean theme in his Oration in Praise of Constantine, defining ten as the sum of the numbers from one to four, and calling ten ‘a full and perfect number’, since it contains ‘every kind and measure of all numbers, proportions, concords, and harmonies’.109 The fact that the Canon Tables proceed in descending order from parallels between four, then three, then two gospels, and finally passages unique to each gospel reveals a pattern of 4-3-2-1, highlighting the mathematical relationship made explicit in the passage from the Oration. Thus, both the number of Canon Tables and the progression within them were probably intended to represent the sense of ‘equilibrium, commensurability, and wholeness’ inherent in the number ten.

Further evidence on this point can be found elsewhere in Eusebius’ corpus, as well as among the later users of his Canon Tables. Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History may have originally been published with fewer books, but the final version consisted of ten, and in the preface to the tenth one he justified the addition of the final book by asserting that it was ‘reasonable’ to end with ‘a perfect number’ (εἰκότως…ἐν ἀριθμῷ τελείῳ).110 If he thought it necessary to explain the number of books of his Ecclestiastical History in this manner, it is no stretch to suppose that he thought the same with respect to his Canon Tables, though he never said as much explicitly. Certainly later interpreters thought that this number was deliberately chosen, or, perhaps more accurately, divinely necessary. Victor of Capua in the sixth century asserted that the number of Canons was determined ‘according to reason and a natural rule’ (ratione et regula naturali), since no other number, either less or more than ten, was possible.111 Similarly in the twelfth century, the Syriac author Dionysius bar Salibi argued that Eusebius established ten tables because ‘the number ten is born from the number four. How? Consider: four, three, two, and one. Behold these add up to ten’.112

Hence, both in the creation and in the reception of Eusebius’ Canon Tables, the fact that there were exactly ten tables was taken to be deeply symbolic. One might object that this is merely a post hoc justification for what is in fact an arbitrary number, and it is certainly true that the Eusebian paratext would function just as well as a cross-referencing system if its creator had numbered them consecutively up to thirteen rather than artificially stopping at ten. Nevertheless, the decision to have only ten tables does reflect an aspect of Eusebius’ own understanding of his project, one that otherwise would be easy for those who live in a world saturated with numeric matrices to miss. For him as well as for the users of his paratext, the ten canons were thought to illustrate the deep concord that existed between the divine revelation in the fourfold gospel and the divinely created cosmos. Moreover, the fact that the number ten was understood to be not simply a ‘perfect number’ but also that which gave ‘order’ to the other numbers makes it a particularly apt analogy for the function that the Eusebian paratext performs in relation to the text of the gospels. Just as Ps-Iamblichus had stated that ‘things from heaven to earth, existing harmoniously according to the principles in [the decad], are found, both in general and in particular, to have been ordered by [the decad]’,113 so too the reader of the four gospels could find the divine revelation contained therein ‘ordered’ by Eusebius’ ten tables.

There is further, unnoticed, material from the Oration in Praise of Constantine that highlights the resonances that I am arguing are implicit in the visual presentation of Eusebius’ Canons. The passage cited by Nordenfalk in which Eusebius mentions the formula 1+2+3+4=10 occurs in a long discussion of the divine ordering of the cosmos, and Eusebius’ discourse about these cosmological themes at times sounds almost like a description of his Canon Tables. He begins by pointing out that ‘eternity’ (αἰών) is ‘indestructible’ and ‘endless’ and ‘will not submit to mortal comprehension’, yet the divine ‘Sovereign and Master’ is able to ‘ride it from above’, using his wisdom like reins to control it. The manner of the deity’s control is specified when Eusebius says that he ‘punctuates’ (κατεβάλετο) the monadic, undifferentiated unity of eternity with the ‘complete harmony’ (σὺν ἁρμονίᾳ τῇ πάσῃ) of months, dates, seasons, and years, thereby ‘circumscribing it with manifold boundaries and measurements’. In other words, although eternity is ‘alike in all its parts (or rather has no parts and is indivisible)’,

[God] has, by marking it off into intermediate sections and dividing it like an extended straight line cut with compass points, established a great multitude in it. Thus, though [eternity] is one and comparable to a monad, he has delimited it with all kinds of numbers, causing its formlessness to subsist as a polymorphic diversity.

ὁ δὲ μέσοις αὐτὸν διαλαβὼν τμήμασι καὶ ὥσπερ εὐθεῖαν γραμμὴν εἰς μῆκος τεταμένην διελὼν κέντροις πολὺ πλῆθος ἐν αὐτῷ κατεβάλετο, ἕνα τε ὄντα καὶ μονάδι παρεικασμένον παντοίοις κατεδήσατο ἀριθμοῖς, πολύμορϕον ἐξ ἀμόρϕου τὴν ἐν αὐτῷ ποικιλίαν ὑποστησάμενος.114