5

Canon Tables 2.0

The Peshitta Version of the Eusebian Apparatus

With this chapter we shift our focus back to the east, to consider the distinctive way in which the Canon Tables system was passed down in Peshitta gospel manuscripts. Chronologically speaking, this chapter picks up only shortly after the last one left off, since the editorial work we are to consider most likely took place in the fifth century, though evidence for it survives only in manuscripts dating from the sixth century and onwards.1 The historical sources that are examined in this chapter are also of a different sort from those considered previously. Whereas the last chapter was a close reading of an exegetical treatise that relied upon the paratextual apparatus, the focus in this chapter is on the apparatus itself as it appears in Syriac, specifically Peshitta, gospelbooks. The reason for this is that in the Syriac tradition there emerged an entirely unique version of the Canon Tables that enhanced the potential in Eusebius’ original system to make an even more powerful cross-referencing paratext. We might call this version 2.0 of Eusebius’ technology for ordering the textual knowledge found in the fourfold gospel. This revised system has been known about since the nineteenth century,2 but very little work has been done examining the differences between it and Eusebius’ original.3 The purpose of this chapter is to demonstrate the way in which this revision accomplished a fine-tuning of Eusebius’ invention, allowing for a closer alignment between text and paratext and a corresponding enhancement in the precision of the system as a reference and citation tool.

To set the stage, a brief survey of the history of the gospels in Syriac is necessary.4 The earliest version of the gospel in Syriac was probably the so-called Diatessaron

of Tatian, based on the fact that it appears to have been the most common gospel text

in use in our earliest sources such as Aphrahat and Ephrem, and based on evidence

that it influenced later Syriac translations of the gospels.5 However, by at least the fourth century there also existed a translation of the four

gospels that was known as ‘The Gospel of the Separated Ones’  to distinguish it from Tatian’s version, which went under the title ‘The Gospel of

the Mixed Ones’

to distinguish it from Tatian’s version, which went under the title ‘The Gospel of

the Mixed Ones’  .6 This translation survives only in three incomplete manuscripts dated to the fourth,

fifth, and sixth centuries, though it may have originated as early as the third.7 Although Ephrem (d. 373) worked primarily with Tatian’s version, and authored a commentary

on it,8 he also clearly was aware of the separate gospels as well, demonstrating that both

versions must have been in circulation in his day.9

.6 This translation survives only in three incomplete manuscripts dated to the fourth,

fifth, and sixth centuries, though it may have originated as early as the third.7 Although Ephrem (d. 373) worked primarily with Tatian’s version, and authored a commentary

on it,8 he also clearly was aware of the separate gospels as well, demonstrating that both

versions must have been in circulation in his day.9

Just as the Old Latin was superseded in the West by Jerome’s Vulgate in the late fourth century, so also this Old Syriac translation of the gospels was surpassed by a revised version known as the Peshitta, which was produced some time in the late fourth or early fifth century and became the most commonly used version among all branches of Syriac-speaking Christianity. It was once thought that Rabbula, bishop of Edessa from 411/12 until 435/36 ce, was responsible for this translation, but this idea has since been abandoned in light of the fact that citations of the Peshitta seem to appear earlier than Rabbula.10 As a result, it is impossible to know what person or persons undertook this translation work, which represents ‘a revision of the Old Syriac on the basis of the Greek’11 rather than an entirely new translation. This is a most unfortunate situation, for the revised version of the Eusebian apparatus that is the focus of this chapter appears for the first time in Peshitta gospel manuscripts, and the consistency with which it occurs in them suggests that the updating of the Greek paratext was undertaken in connection with the new translation, just as Canon Tables entered the Latin world around the same time via Jerome’s Vulgate.

In the early sixth century, a further revision of the New Testament was sponsored by Philoxenus of Mabbug (d. 523), though it survives only in quotations and not via direct manuscript evidence. Finally, in the early seventh century, specifically 615/616 ce, yet another revision was produced by Thomas of Harkel, who had been bishop of Mabbug before moving to a monastery in Egypt. The so-called Harklean version ‘marks the zenith of literalism in Syriac representation of Greek’,12 and the surviving manuscripts of it demonstrate an inconsistency in their presentation of the Eusebian paratext. Some, (‘perhaps the majority’ according to Sebastian Brock13) revert back to the original Greek version of Eusebius’ system, though others preserve the revised paratext as it is found in Peshitta manuscripts. In the sole published edition of the Harklean Eusebian apparatus, Samer Soreshow Yohanna makes no mention of the alternate Peshitta version, and comments that the manuscripts used for his edition tend to closely adhere to the version printed in NA28.14 Presumably, then, Thomas of Harkel, in keeping with his goal of representing the Greek text of the gospels as precisely as possible, reverted back to the original Greek version of Eusebius’ system. The Harklean translation of the gospels never won as wide acceptance as the Peshitta, with the result that the revised version of the Canon Tables remained the more common one in use among Syriac-speaking Christians.

The aim of the present chapter is to provide the fullest analysis to date of this Peshitta revision and its relation to the Eusebian original. Three aspects of it must be considered: first, the Peshitta version of Eusebius’ prefatory Letter to Carpianus, which departs in some respects from the Greek original; second, the tabular concordance that typically appears in the lower margin of the page in Peshitta gospelbooks; and third, the additional sections in each gospel that occur in the Peshitta and the corresponding new parallels created from them. By far the most significant departure of the Peshitta version of the Canon Tables from the Greek original, and that which justifies calling it Canon Tables 2.0, is the last of these elements, though I suggest all three features were a part of a single project to overhaul and enhance Eusebius’ edition so that the newest translation of the gospels in Syriac would be equipped with an improved paratextual apparatus.

The Syriac Version of Eusebius’ Letter to Carpianus

The first thing to stress about the Peshitta version of Eusebius’ Letter to Carpianus (see fig. 25) is that it is, on the whole, an accurate translation, and what modifications are present cannot be explained as arising from a misunderstanding of how the marginal apparatus works. It is important to emphasize this point in view of the fact that it was not always the case, as can be seen, for example, with the Ge‘ez version of the letter, which departs much more from the original.15 In contrast, the Syriac mostly follows closely, often word for word, the Greek original. In what seems to be the only comment on this question in the secondary literature, G. H. Gwilliam observed that ‘the earlier part of [the letter] is a fair rendering of the original, but the latter part has become a paraphrase in the attempt to make the somewhat obscure Greek intelligible’.16 Gwilliam’s assessment is generally speaking true, but it is also the case that in the additions the Syriac translator made to Eusebius’ original we can see his own understanding of the Eusebian paratext, which represents a further stage of development in the reception of the apparatus. The changes made by the translator have two primary effects, the first related to Ammonius’ work and its relation to Eusebius’, and the second related to a shifting of emphasis from the ten tables to the marginal enumeration within each gospel.17

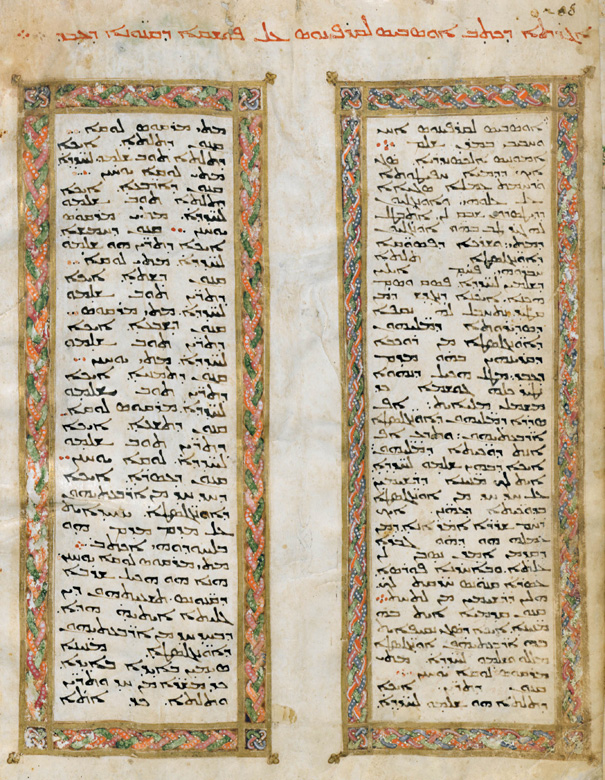

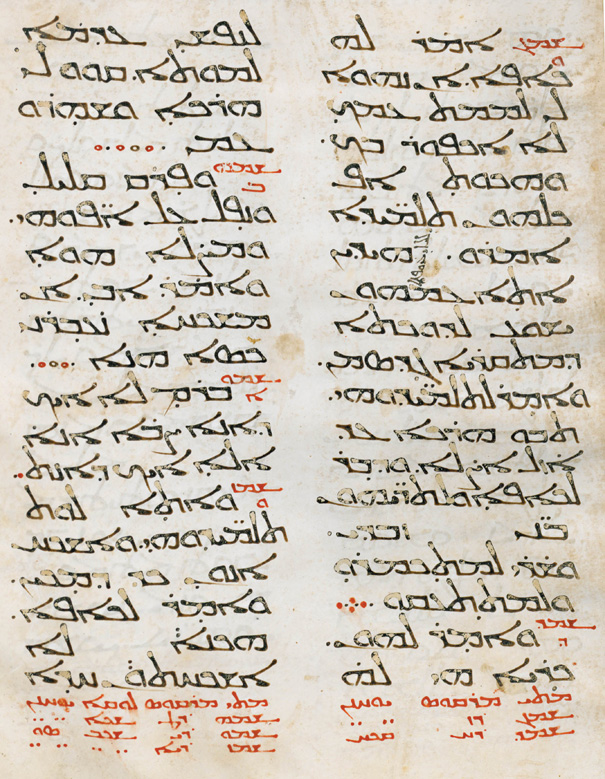

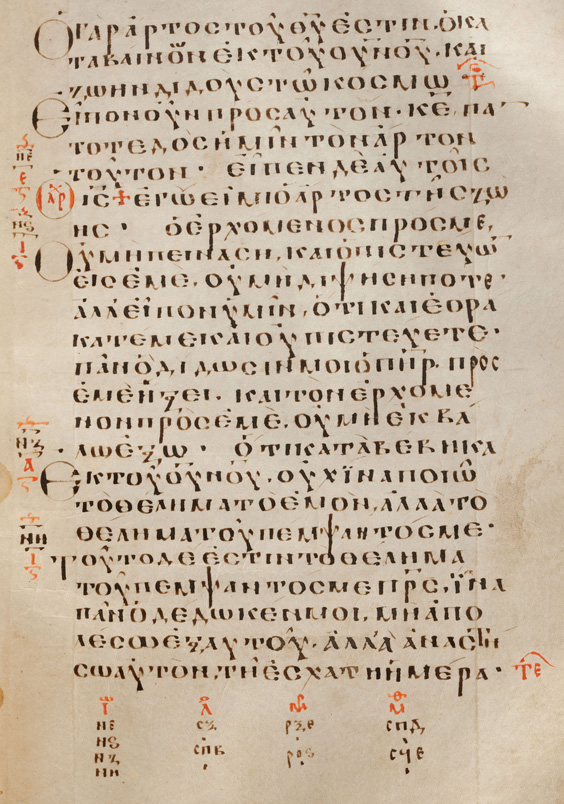

Fig. 25. First half of the Letter to Carpianus in the Rabbula Gospels (sixth c.).

Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, MS. Plut. 1.56, fol. 2v

First, whereas Eusebius used a single verb to describe Ammonius’ modus operandi, asserting that he ‘placed’ passages from Matthew ‘alongside’ (παραθείς) those from the other gospels,18 the Syriac translator expands on the original by using four verbs. In this version

Ammonius ‘closely attended to the Gospel of Matthew, and he collated the rest of the

sections of the three evangelists that were like it [i.e., Matthew]. Those that agreed

with one another he cut into pieces and placed them’

.19 The translator has here provided a much fuller description of the process Ammonius

went through to form his edition, making explicit what was implied by Eusebius’ succinct

account. The verb

.19 The translator has here provided a much fuller description of the process Ammonius

went through to form his edition, making explicit what was implied by Eusebius’ succinct

account. The verb  is used elsewhere to refer to the scribal collation of multiple manuscripts of the

same text,20 and this comparative sense is surely what is in view here—Ammonius sought and collated

those passages of the other three gospels that were similar to passages in Matthew

and placed them alongside one another. The Syriac text also brings out much more explicitly

the unintended, even violent, consequences of his actions. The verb

is used elsewhere to refer to the scribal collation of multiple manuscripts of the

same text,20 and this comparative sense is surely what is in view here—Ammonius sought and collated

those passages of the other three gospels that were similar to passages in Matthew

and placed them alongside one another. The Syriac text also brings out much more explicitly

the unintended, even violent, consequences of his actions. The verb  (‘to cut’) is not only cognate with the word here used for ‘section’ (

(‘to cut’) is not only cognate with the word here used for ‘section’ ( itself a rough equivalent to the Greek περικοπή used by Eusebius), but also ties in with the description of the text as a ‘body’

itself a rough equivalent to the Greek περικοπή used by Eusebius), but also ties in with the description of the text as a ‘body’  that occurs in the lines that follow.

that occurs in the lines that follow.

The translator also made a change that emphasized the relation of Ammonius’ work to

that of Eusebius. Whereas Eusebius had said that ‘in order that you might be able

to know the particular passages in each evangelist where they were moved by love for

the truth to speak about the same things, I took my starting points from the labour

of the aforementioned man’ (εἰδέναι ἔχοις τοὺς οἰκείους ἑκάστου εὐαγγελιστοῦ τόπους, ἐν οἷς κατὰ τῶν αὐτῶν ἠνέχθησαν φιλαλήθως εἰπεῖν, ἐκ τοῦ πονήματος τοῦ προειρημένου ἀνδρὸς εἰληφὼς ἀφορμὰς),21 the Syriac translator has rendered the phrase φιλαλήθως εἰπεῖν as a statement from Eusebius himself: ‘As a lover of the truth, I say that we took

for ourselves the occasion from the labour of that man [i.e., Ammonius] about whom

we spoke previously’

.22 Gwilliam pointed out that the translator apparently punctuated the Greek with a full

stop after ἠνέχθησαν, beginning a new sentence with the φιλαλήθως εἰπεῖν that follows.23 This is true, but it is also the case that the translator in fact omitted translating

ἠνέχθησαν altogether. In Eusebius’ original, the words beginning with εἰδέναι ἔχοις in the above quotation were a continuation of a ἵνα clause begun earlier describing the purpose of his work, and with the words ἐκ τοῦ πονήματος Eusebius began the main clause describing his own actions to produce the Canon Tables

apparatus. The Syriac translator, however, has provided a new main clause on which

the ἵνα clause depends (on which more shortly), with the result that φιλαλήθως εἰπεῖν must begin a new sentence.

.22 Gwilliam pointed out that the translator apparently punctuated the Greek with a full

stop after ἠνέχθησαν, beginning a new sentence with the φιλαλήθως εἰπεῖν that follows.23 This is true, but it is also the case that the translator in fact omitted translating

ἠνέχθησαν altogether. In Eusebius’ original, the words beginning with εἰδέναι ἔχοις in the above quotation were a continuation of a ἵνα clause begun earlier describing the purpose of his work, and with the words ἐκ τοῦ πονήματος Eusebius began the main clause describing his own actions to produce the Canon Tables

apparatus. The Syriac translator, however, has provided a new main clause on which

the ἵνα clause depends (on which more shortly), with the result that φιλαλήθως εἰπεῖν must begin a new sentence.

Without the ἠνέχθησαν, the infinitive εἰπεῖν stands alone at the head of a new sentence, an odd construction in Greek, to say

the least. Perhaps the translator was working from a defective manuscript that read

εἶπον (‘I say’) in place of εἰπεῖν (‘to say’). Alternatively, given that just prior to this sentence the translator

departed from his source text by inserting a lengthy new clause without any parallel

in Eusebius’ letter, it may be that when he returned to his exemplar this seemed the

best way to pick back up following the text of his source. Whatever the exact cause,

or whether or not the change was deliberate, the effect of this alteration is to grant

greater prominence to the relationship between the works of Ammonius and of Eusebius.

Eusebius’ statement in this new version takes on an oath-like quality, defending the

legitimacy of his task of composition by appealing to his motivation as a ‘lover of

the truth’. The word that the translator used for Eusebius’  which has much the same semantic range, though he has used the singular in place

of Eusebius’ plural, which, as I argued in chapter 2, is crucial for interpreting its meaning.24 Nevertheless, as in the Greek version, it is Ammonius and Eusebius that stand together

as collaborators in this version of the letter, though in the Syriac edition the translator

has been more explicit about Ammonius’ method and has enhanced Eusebius’ declaration

of his debt to his predecessor.25

which has much the same semantic range, though he has used the singular in place

of Eusebius’ plural, which, as I argued in chapter 2, is crucial for interpreting its meaning.24 Nevertheless, as in the Greek version, it is Ammonius and Eusebius that stand together

as collaborators in this version of the letter, though in the Syriac edition the translator

has been more explicit about Ammonius’ method and has enhanced Eusebius’ declaration

of his debt to his predecessor.25

The Syriac translator similarly inserted a new sentence in the first half of the letter that referred to the enumeration within each gospel, something that Eusebius himself did not mention until the latter half of the letter. Indeed, the structure of the letter makes this the main focus of its first half:

in order to preserve the whole body perfectly complete, along with the order of the four evangelists’ words, and in order that you might know also the passages of the words in which they [i.e., the words] agree with one another, there are numbers inscribed for you above each one of the evangelists in the passages that are appropriate.

The italicized words in the translation mark the additional material inserted by the translator, and, though they are in keeping with the intent of Eusebius’ original letter, they do subtly shift the emphasis, so that the focus is not primarily upon the ten prefatory tables, but at least equally, if not more, upon the marginal numbers within each gospel.

This emphasis on the sectional enumeration comes out again even more clearly at the end of the letter, which represents the most significant change made by the Syriac translator. Once he had completed his rendering of Eusebius’ original, the translator added an entirely new paragraph that recapitulated much of the preceding material:

Therefore, these numbers have been appointed in order that the words of the four evangelists might not be cut off one from after another, and so that the sequence of their arrangement might not be destroyed. Rather, only the numbers change in relation to one another, in order to show that the evangelists agree with one another, and in order that the reading of the arrangement of the words of those four might remain intact, that is, Matthew, Mark, Luke, John.

Since this paragraph was not actually a translation at all, but the translator’s expansion

on his source text, we can observe here those aspects of Eusebius’ system that seemed

to him most significant.28 As he had already highlighted with his addition to the first paragraph, here again he points out the danger that

the evangelists’ words might be ‘cut’, that violence might be done to the body of

the text. He also again repeats the danger that their ‘sequence of arrangement’  might be corrupted, this phrase having already been used in the first half of the

letter to translate Eusebius’ τὸν τῆς ἀκολουθίας εἱρμόν. However, the object of the ‘cutting’ appears subtly different here from the usage

of the concept in the first part of the letter. Whereas earlier the translator made

explicit that Ammonius’ method involved ‘cutting up’ bits and pieces of individual

gospels to align them with Matthew, the threat in this last paragraph has in view

the unity of the fourfold gospel as a whole. In other words, the translator wants

his readers to know that the Canon Table apparatus is designed to demonstrate the

unity of these four texts as a corpus, a ‘body’ (‘the evangelists agree with one another’),

as well as the integrity of each individual text in the corpus (‘the reading of the

arrangement’). Although the latter concern reflects Eusebius’ own description, nowhere

in the original Letter to Carpianus did he claim to demonstrate that the four gospels ‘agree’ with one another and so

should not be separated. Rather, he simply provided readers with a tool to find passages

where the evangelists ‘have said similar things’.The Syriac reviser therefore claims

more for the apparatus than Eusebius himself explicitly did, as though it vindicated

the inclusion of these four texts in a canon.

might be corrupted, this phrase having already been used in the first half of the

letter to translate Eusebius’ τὸν τῆς ἀκολουθίας εἱρμόν. However, the object of the ‘cutting’ appears subtly different here from the usage

of the concept in the first part of the letter. Whereas earlier the translator made

explicit that Ammonius’ method involved ‘cutting up’ bits and pieces of individual

gospels to align them with Matthew, the threat in this last paragraph has in view

the unity of the fourfold gospel as a whole. In other words, the translator wants

his readers to know that the Canon Table apparatus is designed to demonstrate the

unity of these four texts as a corpus, a ‘body’ (‘the evangelists agree with one another’),

as well as the integrity of each individual text in the corpus (‘the reading of the

arrangement’). Although the latter concern reflects Eusebius’ own description, nowhere

in the original Letter to Carpianus did he claim to demonstrate that the four gospels ‘agree’ with one another and so

should not be separated. Rather, he simply provided readers with a tool to find passages

where the evangelists ‘have said similar things’.The Syriac reviser therefore claims

more for the apparatus than Eusebius himself explicitly did, as though it vindicated

the inclusion of these four texts in a canon.

Moreover, in this final paragraph the translator explicitly points out the technological

advance that has made possible this unique system. Because the evangelists’ words

can be represented symbolically by numbers, ‘only the numbers change in relation to

one another’. That is, in a gospelbook equipped with this apparatus, the numbers ‘change’

( in the Pael can even mean ‘move from one place to another’) as one reads through

each gospel, showing the relationship of each gospel with its companions from start

to finish, and it is this numeric variability that ensures textual stability. Note

that the ‘numbers’ in view here are the sectional enumeration within each gospel.

In fact, the translator makes no mention in this paragraph of the Canons at all, revealing

again that he thought the sectional enumeration was the most important element of

the system.

in the Pael can even mean ‘move from one place to another’) as one reads through

each gospel, showing the relationship of each gospel with its companions from start

to finish, and it is this numeric variability that ensures textual stability. Note

that the ‘numbers’ in view here are the sectional enumeration within each gospel.

In fact, the translator makes no mention in this paragraph of the Canons at all, revealing

again that he thought the sectional enumeration was the most important element of

the system.

Marginal Concordance Tables in Syriac Manuscripts

The heightened emphasis placed upon the marginal enumeration in the Peshitta Letter to Carpianus is no doubt related to another aspect of the presentation of the Eusebian apparatus in Syriac manuscripts. Peshitta gospelbooks consistently include in the bottom margin of each page a small table showing the section numbers for the passages from the other gospels that are parallel to whatever passages are present on the page that you are reading. Take, for example, fol. 84r of the Rabbula Gospels, which contains the Peshitta version of Matthew 26:35–40 (see fig. 26).29

Fig. 26. Mt §343–7 (= Mt 26:35ff.) in the Rabbula Gospels (sixth c.).

Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, MS. Plut. 1.56, fol. 84r

The right-hand column of text (which is read first), contains two Eusebian sections, numbered in red as ܫܡܓ and ܫܡܕ (that is, 343 and 344), and below the column is written in red the following table:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Matthew | Mark | John |

|---|---|---|

| 343 | 207 | -- |

| 344 | 208 | 128 |

In other words, Mt §343 is parallel to Mk §207 (the dots are placed in the column

for ‘John’ because this is a Canon VI parallel, and so has no Johannine equivalent),

and similarly Mt §344 is parallel to Mk §208 and Jn §128. Similarly, the left-hand

column on this same page contains Matthew sections  and

and  (that is, 345, 346, and 347), and beneath the column of text is written the following

information:

(that is, 345, 346, and 347), and beneath the column of text is written the following

information:

Once again, the chart in the bottom margin informs the reader that Mt §345 is parallel to Mk §209 and Lk §321, and so on for Mt §346 and §347. This is of course the same information that one could find by turning to the tables at the beginning of the codex,30 and in fact these tabular cross-references render the ten prefatory tables somewhat redundant since the reader can now turn directly from one gospel to another without needing to consult the Canons.31 The diminished need for the prefatory Canons corresponds to the fact that the Peshitta Letter to Carpianus downplays the Canons and highlights instead the marginal enumeration within each gospel. Because it simplifies the steps required to access the parallels created by Eusebius—making the intertextual itineraries between gospels more direct by not requiring that one be routed through the Canon Tables themselves—this additional marginal annotation enhances the usability of the Eusebian paratext.32

Given how early and consistently this feature appears in the manuscript tradition, the marginal tables throughout the gospels were probably a part of the system in Syriac manuscripts from the outset. Was it, however, truly an ‘innovation’ of the Syriac translator, as has been assumed?33 In fact, a similar development appears in a number of contemporary Latin manuscripts, such as the fifth-century Codex Sangallensis 1395 (see fig. 27).34 In these manuscripts an enhanced version of marginal annotation also appears on each page, though in the Latin tradition the section numbers for the parallel passages in the other gospels are distributed across the page at various places in the margin beneath each of the corresponding section numbers, rather than being collected together in a tabular format, as they are in Syriac codices. Given the likely dating of the Peshitta translation to the late fourth or early fifth century, this is therefore a feature that appeared roughly simultaneously in Latin and in Syriac. Should we then view these as parallel developments that occurred independently of one another or is it possible that they are in some way related? An influence from a Syriac source directly upon a Latin one or vice versa appears unlikely in the period in question, though not impossible.

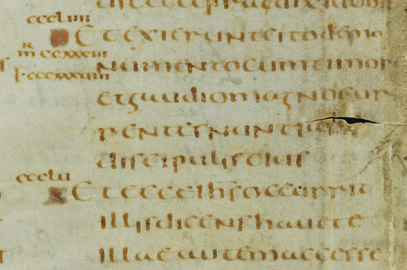

Fig. 27. Mt §354–5 in Codex Sangallensis 1395 (first half of fifth c.). Codex Sangallensis 1395 is the oldest copy of the Vulgate gospels and was possibly copied within Jerome’s own lifetime. Here we see two sections from the Gospel of Matthew: Mt §354 and §355. Mt §354 is a Canon II passage, parallel to Mk §233 and Lk §338, which are both listed in the margin beneath the red ‘II’. However, Mt §355 is a passage unique to Matthew (note the red ‘X’ for the Canon number), so no parallel passages are listed for it.

St Gall, Stiftsbibliothek 1395, p. 132

Such a supposition is, however, unnecessary, since there is also evidence of the enhanced marginal annotation in the Greek manuscript tradition, though it has hitherto been largely overlooked. Sebastian Brock, for example, mentioned in passing that a few Greek manuscripts present this same system, but asserted that they are all much later than the earliest Syriac gospel codices.35 For the most part he was correct, in that the handful of relevant Greek manuscripts are mostly later, such as the ninth-century Codex Basilensis A.N.III.12, known as manuscript Ee in the numbering system used by the INTF (see fig. 28).36 The New Testament textual critic Casper René Gregory listed this manuscript, along with seven other Greek ones, which all included such tables in the bottom margin of the page, most of them dated between the ninth and twelfth centuries.37 However, it has recently been pointed out that there is a fragmentary Greek manuscript dated to the sixth century that also preserves evidence of the same kind of marginal table that appears in contemporary Peshitta manuscripts.38 In addition to the Syriac, Latin, and Greek manuscripts just noted, mention should also be made of Codex Argenteus, a sixth-century manuscript containing the Gothic version of the gospels in gold and silver ink on purple parchment. It too includes in the bottom margin of each page the same tabular concordance, the only difference being that here the tables are housed within mini-arcades, an additional decorative flourish no doubt inspired by the architectural motifs that housed the now lost Canons at the start of the codex (see fig. 9 in the introduction).

Fig. 28. Jn §55–8 (Greek numerals ΝΕ, ΝϚ, ΝΖ, ΝΗ) in Codex Basilensis A.N.III.12 (ninth c.). The table in the bottom margin shows the parallel passages from the other three gospels, in the sequence John-Luke-Mark-Matthew. The parallel Jn §55, Lk §266, Mk §165, Mt §284 (Jn §ΝΕ, Lk §ϹΞϚ, Mk §ΡΞΕ, Mt §ϹΠΔ = Jn 6:35a, Lk 22:19, Mk 14:22, Mt 26:26) is discussed in chapter 3. Here Eusebius has singled out the sentence εἶπεν δὲ αὐτοῖς ὁ Ἰ(ησοῦ)ς· ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ἄρτος τῆς ζωῆς (beginning on line 6) and joined it to Jesus’ statements from the Last Supper accounts in the synoptics. Note that the scribe here has made a mistake, writing ϹΞ (= 260) rather than ϹΞϚ (= 266) in the first row of the column for Luke. The correct number is, however, given on fol. 236r where the Lukan passage occurs.

Basel, Universitätsbibliothek, A.N.III.12, fol. 269r

It is therefore the case that by the fifth and sixth centuries, there are examples of gospelbooks in Greek, Latin, Gothic, and Syriac that contain the enhanced marginal annotation, so this cannot be viewed as a distinctive feature of the Syriac tradition.39 Peshitta manuscripts are remarkable only for the fact that this became a regular feature of their mis-en-page, whereas it was never universal in the Latin tradition and never seems to have been common in Greek codices. That it appears so consistently in the Syriac tradition is probably due to the fact that, as already suggested, it was an original part of the translation of Eusbius’ apparatus into the language and continued to be copied thereafter as a standard feature, whereas in the Greek and Latin manuscript traditions it was a subsequent development. With the evidence we have at hand, it is neither possible nor necessary to determine in which of these languages the additional marginal annotation first appeared. Greek might seem like the most likely option, with the new concept then radiating out to both the Syriac and the Latin worlds, though it is also possible that this was an innovation that first occurred in a Latin manuscript, and that it then was transmitted back into the Greek tradition, and from there into Syriac.

The Peshitta Revision of Eusebius’ Sectioning and Parallels

In the last section it might have seemed that I was detracting from the uniqueness of the Syriac tradition by placing it in a wider context, demonstrating that the tabular concordances usually found in them are not a unique feature isolated to Syriac codices. However, there is one other respect in which the version of the paratextual system that appears in Peshitta gospelbooks is completely without parallel. All Peshitta codices that have Canon Tables carry a revised version of Eusebius’ sectioning that encodes a more precise citation system, which allows for an even greater degree of comparative analysis of the similarities and differences amongst the gospels. This revision was accomplished by further subdividing the sections within each gospel. The chart below demonstrates the differences in the original and revised versions:

As the above numbers indicate, the person responsible for this revised version was able to increase the number of sections in each gospel by around a fifth. With a larger number of sections in each gospel, there is greater scope for making parallels between gospels. Accordingly, we find a greater number of parallels listed in most of the ten Canons:

The first thing that is immediately apparent from the above figures is the uneven distribution of the new parallels created by the more precise sectioning. Quite unexpectedly, three Canons actually present fewer parallels in this new system than in Eusebius’ original: Canons III (Mt–Lk–Jn), IV (Mt–Mk–Jn), and IX (Lk–Jn). Moreover, other Canons drastically increased, such as Canons VII (Mt–Jn) and VIII (Mk–Lk), which have 157% and 77% more parallels in the new version, though this high percentage of increase is partially due to the small size of these lists to begin with. It is also striking that the reviser has identified 37% more unique material in Mark than Eusebius had done, a figure no doubt related to the fact that the number of sections in Mark also increased proportionally more than is the case for the other gospels (24%).

Analysing examples of the changes made in each of the Canons will give us a better picture of the revision the Syriac scribe has made to Eusebius’ original. I have tried as far as possible to choose examples drawn from a range of types of passages, including narrative and discourse. Note that in what follows I will use a superscript ‘E’ and ‘S’ to clarify whether the sections I am citing belong to Eusebius’ original or to the Syriac revision.

Canon I

All four gospels preserve a statement from John the Baptist that draws a contrast between his own status and ministry and that of the ‘one coming after’ him. Eusebius accordingly placed all four of these passages in Canon I as parallel to one another:40

The Syriac version retains this parallel but subdivides it into two Canon I parallels. Thus we have the following:41

In large measure, these sections are identical to Eusebius’ original. The only exception is that the final lines of the passages from the Synoptic sections have been broken off to form new sections, which now are joined to another new section from the Gospel of John to create a new Canon I parallel. Eusebius had included John 1:33 in a larger section comprising John 1:32–4 (Jn §15E), which formed a Canon I parallel about the descent of the Spirit at Jesus’ baptism. The Syriac reviser excerpted John 1:33 from this Eusebian section because he recognized that it presented a verbal and thematic similarity to a statement from the Synoptics about the sort of baptism that Jesus would bring to pass. This new section therefore highlights the distinctiveness of Jesus’ baptism, that it is accomplished in the Holy Spirit and in fire, though it also demonstrates that further subdivision would have been possible for a reviser who was even more scrupulous about what passes for similarity. While all four gospels state that Jesus will baptize ‘in the Holy Spirit’, only Matthew and Luke add the additional feature of baptism ‘in fire’. This dissimilarity could be taken as grounds for making the prepositional phrases ‘in fire’ in the Matthean and Lukan accounts into two new sections, forming a Canon V parallel, but the Syriac reviser chose not to do so. This example illustrates that, although the Peshitta version is more precise than Eusebius’ original, still further precision would have on occasion been possible, though the additional utility of the greater precision in this instance would have been negligible.

It is pertinent at this point to recall the discussion from chapter 3 about the nature of Eusebius’ parallels. Placing two passages alongside each other in a Canon Table implies that they present some kind of similarity to each other, though it does not specify the degree or nature of that similarity. The Syriac reviser often seems to assume that a greater degree of correspondence is necessary for two passages to be set in parallel to each other, as in the above example wherein he highlights the verbal parallel in the statements from John the Baptist across all four gospels. At times, however, the Syriac revision expands Eusebius’ system, not by subdividing and producing greater verbal precision, but instead by adding more passages to a set of thematic parallels originally created by Eusebius. An example is the treatment of Peter’s confession of Christ recorded in the Synoptics. Eusebius had included as a Canon I parallel the following passages: Mt §166E, Mk §82E, Lk §94E, and Jn §17E, 74E (=Mt 16:13–16; Mk 8:27–9a; Lk 9:18–20; Jn 1:41–2, 6:68–9).42 In the former three passages Peter confesses Jesus as ‘Christ’, while in the first Johannine passage it is in fact Andrew, Peter’s brother, who makes this confession to Peter. We might then assume that the Peshitta version would split apart the Synoptic and Johannine passages, in view of the difference between them. In fact, however, the Peshitta lists even more passages: Mt §201S, Mk §103S, Lk §119S, Jn §20S, 23S, 39S, 82S, 107S (=Mt 16:16; Mk 8:29b; Lk 9:20b; Jn 1:41–2, 1:49–2:11, 4:42b, 6:68–9, 11:27b). Here the Syriac reviser has added three more Johannine parallels to the passages containing Peter and Andrew’s confession, and these recount the similar confessions made by Nathanael, the Samaritan villagers, and Martha. The Syriac reviser has apparently recognized the thematic similarity of Eusebius’ original set of passages and decided on this occasion to retain and even increase the number of voices confessing Jesus as the Messiah. In other words, strict verbal or historical correspondence was not the only criterion used in revising Eusebius’ system.

Canon II

The story of the healing of a paralytic is a typical example of the kinds of changes made with respect to Canon II. Eusebius had treated these episodes as large chunks of text, presenting them as a Canon I parallel:

The Syriac, however, subdivides the leading Matthean passage into four sections, alternating back and forth between Canon I and Canon II:

The other portions of Eusebius’ original Johannine section that are not used in the Canon I parallels above (Jn 5:1–4, 9c–10 = Jn §45S, 48S) are now relegated to Canon XJn as material unique to the fourth gospel. The primary goal of these redactional changes is to highlight only those portions of the Johannine episode that have a correspondence with the Synoptic accounts, all of which are otherwise very similar among themselves. The extent of the similarity among the four is simply the introduction of the paralysed man and the successful healing, so these two elements remain Canon I passages, as Eusebius had originally indicated. However, with the removal of the distinctly Johannine elements from John 5:1–10, the remaining portions of the Synoptic passages are shifted from Canon I to Canon II. These changes therefore result in the addition of one new Canon I passage, two Canon II passages, and two new Canon XJn passages, illustrating how subdividing a single episode can quickly increase the overall tally of parallels listed in the Tables.

Canon III

The last example demonstrated the Syriac reviser making new parallels by removing portions of text that were, in his estimation, not close enough to warrant inclusion alongside the other passages next to which Eusebius had originally placed them. The Syriac redactor also at times added new passages to existing Eusebian parallels, such as with Matthew 8:13, about the healing of a centurion’s servant. Eusebius had originally presented the conclusion to this episode as a Canon V parallel:

| Mt §66E | Lk §66E |

|---|---|

| Mt 8:13 And to the centurion Jesus said, ‘Go; let it be done for you according to your faith’. And the servant was healed in that hour. | Lk 7:10 When those who had been sent returned to the house, they found the slave in good health. |

The Syriac preserves this parallel but adds to it a new section:

| Mt §81S | Lk §84S | Jn §44S |

|---|---|---|

| Mt 8:13 Jesus said to the centurion, ‘Go. May it be for you as you have believed’. And his child was healed at that moment. | Lk 7:10 Then the people who had been sent returned to the house and found that the servant who had been sick was well. | Jn 4:50 ‘Go’, Jesus told him, ‘your son is saved’. The man believed in the word Jesus told him, and went away. Jn 4:51 As he was going down, his servants met him and reported the good news, telling him, ‘Your son lives’. Jn 4:52 He asked them, ‘At what time did he get well?’ ‘The fever left him yesterday at the seventh hour’, they told him. Jn 4:53 The boy’s father realized it was in that hour that Jesus had told him, ‘Your son lives’, and he and his entire household believed. Jn 4:54 Now this was the second sign Jesus did after coming from Judea to Galilee |

By adding a Johannine passage alongside the Matthean and Lukan ones, the parallel moves from Canon V to Canon III. The new Johannine passage had been a part of a larger Eusebian section, comprising John 4:46b–54 (=Jn §37E), so this is another example of a new parallel created by subdivision of a Eusebian section. Nevertheless, with his addition of the new Johannine section to the existing Canon V parallel, the Syriac redactor was still following Eusebius’ lead, since Eusebius himself had coordinated Jn 4:46b–54 as a whole with the earlier portions of the healing episodes in Matthew and Luke (Mt 8:5–10; Lk 7:1–9; Jn 4:46b–54 = Mt §64E; Lk §65E; Jn §37E). What the Syriac author has done, therefore, is to fine-tune Eusebius’ treatment of these passages by more correctly aligning the conclusion to the three episodes as a parallel, rather than having just one large Johannine section parallel to the first half of the Matthean and Lukan episodes.

Canon IV

I pointed out above that the number of Canon IV parallels actually decreased as a result of the changes introduced by the Syriac redactor. We can see one example of how such a reduction occurred by examining the treatment of Matthew 12:14 and parallels. Eusebius had created the following Canon IV parallel:

| Mt §117E | Mk §26E | Jn §95E |

|---|---|---|

| Mt 12:14 But the Pharisees went out and conspired against him, how to destroy him. | Mk 3:6 The Pharisees went out and immediately conspired with the Herodians against him, how to destroy him. Mk 3:7a Jesus departed with his disciples to the sea, | Jn 11:53 So from that day on they planned to put him to death. Jn 11:54 Jesus therefore no longer walked about openly among the Jews, but went from there to a town called Ephraim in the region near the wilderness; and he remained there with the disciples. |

The Syriac retains these passages as a parallel, but adds a Lukan episode:

In this instance, Luke 6:11 was originally, for Eusebius, included in a larger section consisting of Luke 6:6–11 (=Lk §42E), but the Syriac redactor has broken off this verse to create a new section, so that he can add it to an existing Canon IV parallel, thereby turning it into a Canon I parallel. Here again, however, this is not really a new parallel, but rather a tidying up of Eusebius’ original version. The above verses in Matthew, Mark, and Luke represent the conclusion to the story of the healing of the man with a withered hand. Although all three accounts end with the Pharisees conspiring against Jesus, Eusebius took only the concluding statements from Matthew and Mark to make them a distinct parallel with the Johannine passage, presumably because all three speak of the desire of Jewish leaders to kill Jesus. Although the Lukan ending to the story is not as dramatic, with a vaguer report about the response of Jesus’ enemies, the Syriac reviser decided that it too should be included alongside the other three passages. The impact of this change is that Canon IV loses a parallel, while Canon I gains one.

Canon V

The way in which the Syriac author reworked the accounts of Jesus’ temptations is a useful example of the kind of editorial work he undertook. Matthew and Luke uniquely record a series of three temptations, so Eusebius placed these passages in Canon V:

| Mt §16E | Lk §16E |

| Mt 4:2–10 | Lk 4:2b–13 |

However, Matthew and Luke, despite recording the same three temptations, disagree on the order in which they occurred, a divergence that Eusebius’ parallel does not reflect. The Syriac redactor makes this divergence explicit by splitting the original two sections in Matthew and Luke into three sections in each gospel:

| Mt §20S | Lk §19S |

| Mt 4:2–4 | Lk 4:2b–4 |

| Mt §21S | Lk §21S |

| Mt 4:5–7 | Lk 4:9–12 |

| Mt §22S | Lk §20S |

| Mt 4:8–10 | Lk 4:5–8 |

Once again, this is an example of the Syriac author working with Eusebius’ original sections, further subdividing them to make more explicit what is similar and different in these two accounts.

Another example of a new Canon V section comes from the Sermon on the Mount. Eusebius had made Matthew 5:41–3 a section (Mt §39E) and placed it in Canon XMt as unique to the first gospel. The Syriac reviser, however, recognized that in fact the middle portion of this passage has a verbal similarity with a Lukan passage and he therefore singled out the relevant portion and joined it with a new Lukan section to create a new Canon V parallel:

| Mt §50S | Lk §68S |

|---|---|

| Mt 5:42 Give to the person who asks you, and do not refuse the one who wants to borrow from you. | Lk 6:30 Give to everyone who asks you, and if someone takes something of yours, do not demand it back. |

The verbal correspondence between the above passages is obvious, so this is an instance in which the Syriac author has corrected what he might have regarded as an oversight on Eusebius’ part. The result is that a single Eusebian Canon XMt passage becomes in the Peshitta two passages in Canon XMt and one passage in Canon V.

Canon VI

Several of the new Canon VI parallels arose because the Syriac reviser removed the Johannine portion of what was originally a Canon IV parallel, leaving only the passages from Matthew and Mark, which now formed a Canon VI parallel. One example is the treatment of the accounts of Jesus on the cross being offered wine to drink. Eusebius had divided the text so as to join the following passages together:

| Mt §333E | Mk §211E | Jn §203E |

|---|---|---|

| Mt 27:34 they offered him wine to drink, mixed with gall; but when he tasted it, he would not drink it. | Mk 15:23 And they offered him wine mixed with myrrh; but he did not take it. | Jn 19:28 After this, when Jesus knew that all was now finished, he said (in order to fulfill the scripture), ‘I am thirsty’. Jn 19:29 A jar full of sour wine was standing there. So they put a sponge full of the wine on a branch of hyssop and held it to his mouth. Jn 19:30a When Jesus had received the wine, he said, ‘It is finished’. |

In contrast, the Peshitta version presents only the following passages:

| Mt §397S | Mk §255S |

|---|---|

| Mt 27:34 They gave him wine vinegar mixed with gall to drink. He tasted it but did not want to drink it. | Mk 15:23 They gave him wine mixed with myrrh to drink, but he did not take it. |

The reason for this change is that the Syriac reviser realized that a more plausible parallel for the Johannine passage was available in the other two gospels. In fact, both Matthew and Mark contain two reports of wine being offered to Jesus. The first is that one above, in Matthew 27:34 and Mark 15:23, which occurs at the beginning of the crucifixion account, just after Jesus arrives at Golgotha. They also, however, have a later account of sour wine being offered to Jesus on a sponge just prior to his death (Mt 27:48; Mk 15:36). The latter two passages were included by Eusebius in a separate Canon II parallel, along with a passage from Luke, who only has one offering of wine to Jesus (Mt §342E; Mk §222E; Lk §323E). The Gospel of John, like Luke, only has one offering of wine, and it is sour wine, occurring just prior to Jesus’ death, like the second offering of wine in Matthew and Mark. In other words, this Johannine passage presents a closer similarity to the passages Eusebius had included in the later Canon II parallel than it does to Matthew 27:34 and Mark 15:23.43 The Syriac reviser accordingly removed the Johannine passage from Eusebius’ Canon IV parallel, reducing it to a Canon VI parallel, and added this passage to the Canon II parallel, to create a new Canon I parallel (Mt §406S; Mk §266S; Lk §370S; Jn §233S).44 The new version rightly highlights that only Matthew and Mark have an initial refusal of the mixed wine, while all four evangelists have a later offering of sour wine on a sponge.

One other new Canon VI parallel warrants mention because it highlights a difference between the text of the gospels in Eusebius’ edition and the text of the Peshitta version. Although Eusebius was aware of the longer ending of Mark, and discussed this as a textual problem in his influential work Quaestiones ad Marinum,45 there is no evidence that he included these verses in his sectional enumeration. In fact, three later gospelbooks explicitly state, following Mark 16:8, ‘until this point Eusebius Pamphilus canonized’ (ἕως οὗ καὶ Ἐυσέβιος ὁ Παμφίλου ἐκανόνισεν).46 It is therefore likely that the edition of the fourfold gospel that he issued with his new apparatus did not include the longer ending, but, even if it did, it must have been unnumbered. The Peshitta, however, did include the longer ending of Mark, and the person responsible for revising Eusebius’ paratext extended the enumeration for Mark to cover these verses, which allowed for the possibility of new parallels between these verses and other passages. One that the reviser highlighted was the following:

| Mt §426S | Mk §288S |

|---|---|

| Mt 28:19 Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, and baptize them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, Mt 28:20 and teach them to obey everything I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, until the end of the age. Amen. | Mk 16:15 ‘Go to all the world’, he said to them. ‘And preach my good news throughout creation’. |

This passage illustrates well one of the effects of the Canon Tables system that I argued for in chapter 3. By enumerating these verses and listing their section number in the Tables, the Peshitta version thereby incorporates them into the canonical space marked out by the Eusebian paratext, clearly demarcating them from that which is extra-canonical and aligning them with unquestionably authoritative passages such as Matthew 28:19–20. The Canon Tables apparatus thereby integrates this passage from the longer ending of Mark into the unified witness of the fourfold gospel.

Canon VII

Sometimes the new parallels created by the Syriac reviser take account of what appear to be trivial narrative details. For example, the introduction to the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew 5:1 was relegated by Eusebius to Canon XMt as unique to Matthew (Mt §24E). The Syriac version, however, juxtaposed this brief statement with a passage from the Gospel of John that appeared in a very different context, prior to the feeding of the 5,000, and thereby created a new Canon VII parallel:

| Mt §33S | Jn §56S |

|---|---|

| Mt 5:1 When Jesus saw the crowds, he went up on a mountain. After he sat down, his disciples approached him, | Jn 6:3 Jesus went up a mountain and sat down with his disciples. |

The common element here is of course Jesus going up on a mountain with his disciples, though the passages that follow have little in common otherwise. It is not obvious what sort of theological or exegetical point could be made of the new parallel, but it at least demonstrates the close attention to detail exhibited by the Syriac reviser, taking account of relatively brief and seemingly insignificant verbal correspondences.

Another example of a new Canon VII parallel is the treatment of the famous statement about Peter as the ‘rock’ following his confession of Jesus as Christ. Eusebius made this a Canon XMt passage (Mt 16:17–19 = Mt §167E) even though, as the Syriac reviser realized, there were parallels with John that might have been exploited. The Syriac version of the apparatus breaks this single section into three new sections, placing the first (Mt §202S) in Canon XMt and the latter two both in Canon VII. Matthew 16:18 (Mt §203S) he joins with John 1:42b (Jn §21S), both statements from Jesus about Peter’s name as ‘Cephas’. Matthew 16:19 (Mt §204S), a promise about the celestial consequence of Peter’s ‘binding’ and ‘loosing’, he paired with a similar Johannine statement about forgiveness of sins spoken to all the disciples in the upper room (Jn 20:23 = Jn §251S). The latter passage had been included by Eusebius in Canon VII alongside a later Matthean statement, also about ‘binding’ and ‘loosing’, directed to all the disciples (Mt 18:18 = Mt §185E = Mt §227S). The Syriac version retains the latter parallel between Matthew 18:18 and John 20:23 but duplicates the Johannine passage alongside the similar statement directed to Peter alone (Mt 16:19). The result is that two different passages from the Gospel of Matthew are now placed in parallel to the same passage from the Gospel of John, thereby linking together all three of the ‘binding and loosing’ and ‘forgiving’ passages in the gospels.

One other new Canon VII parallel should be mentioned, because it reflects a difference

in the text of the gospels used by Eusebius and that of the Peshitta version. The

standard reading of Matthew 28:18 that appears in the Greek gospel tradition is ‘And

Jesus came and said to them, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given

to me”’ (καὶ προσελθὼν ὁ Ἰησοῦς ἐλάλησεν αὐτοῖς λέγων, Ἐδόθη μοι πᾶσα ἐξουσία ἐν οὐρανῷ καὶ ἐπὶ γῆς). The Peshitta, however, adds a subsequent clause to this verse: ‘Jesus drew near

and spoke with them, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me”,

he told them. “As my Father sent me, I am sending you”’

47 The latter portion of this verse no doubt came originally from the post-resurrection

scene in the upper room from the fourth gospel, when Jesus says to the disciples,

‘Peace be with you. As the Father has sent me, so I send you’ (Jn 20:21; Εἰρήνη ὑμῖν· καθὼς ἀπέσταλκέν με ὁ πατήρ, κἀγὼ πέμπω ὑμᾶς). It is possible that the Greek Vorlage from which the Peshitta was made had this rare reading, but it may also have originated

in the melding of Matthew and John that took place in the Diatessaron, in which case

it might have been passed on to the Old Syriac version of the gospels, and then survived

into the Peshitta revision of the Old Syriac.48 Whatever the case, the Syriac reviser of Eusebius’ paratext recognized that the version

of Matthew 28:18b known to him was verbally identical with John 20:21b, so he subdivided

Eusebius’ original sections in each gospel to select the relevant portion (Mt §425S; Jn §249S), and joined them to create a new Canon VII parallel. In this instance the Syriac

reviser was not highlighting a potential parallel omitted by Eusebius, since the Caesarean

historian could not have been aware of it, but was instead adapting his paratextual

system to better suit the text of the Peshitta version.

47 The latter portion of this verse no doubt came originally from the post-resurrection

scene in the upper room from the fourth gospel, when Jesus says to the disciples,

‘Peace be with you. As the Father has sent me, so I send you’ (Jn 20:21; Εἰρήνη ὑμῖν· καθὼς ἀπέσταλκέν με ὁ πατήρ, κἀγὼ πέμπω ὑμᾶς). It is possible that the Greek Vorlage from which the Peshitta was made had this rare reading, but it may also have originated

in the melding of Matthew and John that took place in the Diatessaron, in which case

it might have been passed on to the Old Syriac version of the gospels, and then survived

into the Peshitta revision of the Old Syriac.48 Whatever the case, the Syriac reviser of Eusebius’ paratext recognized that the version

of Matthew 28:18b known to him was verbally identical with John 20:21b, so he subdivided

Eusebius’ original sections in each gospel to select the relevant portion (Mt §425S; Jn §249S), and joined them to create a new Canon VII parallel. In this instance the Syriac

reviser was not highlighting a potential parallel omitted by Eusebius, since the Caesarean

historian could not have been aware of it, but was instead adapting his paratextual

system to better suit the text of the Peshitta version.

Despite his close attention to detail, there are a handful of instances in which the Syriac revision presents what appear to be errors. An example is the treatment of John 7:43 (=Jn §84E), a single verse that Eusebius had placed in Canon XJn. The Syriac revision creates a new Canon VII passage in the verse immediately prior, John 7:42 (=Jn §94S), aligning it with Matthew 2:5–6 (=Mt §5S), a sensible parallel, since both passages speak about the Messiah being born in Bethlehem. However, the Syriac version extends this new section to include Jn 7:43 as well, despite the fact that it has no correspondence with the Matthean passage. It would have made more sense for Jn §94S to conclude with John 7:42, and for John 7:43 to remain a Canon XJn passage. Most likely the Syriac reviser, after marking a new section at the beginning of John 7:42, overlooked that Eusebius had broken the passage at 7:42/43, and mistakenly carried his new Canon VII section further than was necessary.

Canon VIII

Another means of increasing the overall number of parallels is to split apart some of those that Eusebius had originally joined together. For example, Eusebius had originally presented the following parallel in Canon II:

Some of these passages correspond verbally but some are only thematically similar. Note that this is one of the instances in which Eusebius repeated a Matthean passage alongside multiple Lukan passages to create two Canon II parallels. The Syriac version splits the above parallels apart to create new Canon V and Canon VIII parallels:

| Mt §115S | Lk §175S |

|---|---|

| Mt 10:33 but whoever denies me before people, I will also deny him or her before my Father in heaven. | Lk 12:9 but whoever denies me before people will be denied before the angels of God. |

| Mk §107S | Lk §122S |

|---|---|

| Mk 8:38 Anyone who is ashamed of me and my words in this sinful and adulterous generation, the Son of Man will also be ashamed of them when he comes in his Father’s glory with his holy angels. | Lk 9:26 Anyone who is ashamed of me and my words, the Son of Man will be ashamed of them when he comes in his Father’s glory with his holy angels. |

While Eusebius’ original four passages had a common theme but not identical wording, the Syriac has split the four apart into two groups of two that each have a tighter verbal similarity, one about ‘denial’ and one about ‘shame’. Note that in this instance the Syriac reviser has not created any further subdivisions within any of the gospels, but has still increased the overall number of parallels by splitting one Canon II parallel into two parallels, one in Canon V and one in Canon VIII. This alteration achieves greater precision in the cross-referencing system, but also sacrifices some of its utility as a topical index, since the two pairs of passages are now no longer linked.

The longer ending of Mark also created opportunities for new Canon VIII parallels. The story of the two disciples who meet the risen Jesus on the road to Emmaus is a unique Lukan passage (Lk 24:13–35 = Lk §339E), so Eusebius accordingly placed in Canon XLk. However, the longer ending of Mark also makes brief reference to this event (Mk 16:12–13), so the Syriac version connects these two passages as a Canon VIII parallel (Mk §285S; Lk §393S). Once again, the longer ending of Mark is integrated into the rest of the gospel witness to the risen Jesus.

Canon IX

I noted earlier that the number of Canon IX parallels actually decreased in the Syriac version in comparison with Eusebius’ original, from twenty-one to nineteen. In fact, the Peshitta loses seven of Eusebius’ original twenty-one, amounting to a third of Eusebius’ original total, though it then adds five new parallels to mitigate the loss. All of the parallels that are removed have a common feature. On occasion Eusebius presented the same passage in Matthew as parallel to multiple passages in other gospels. The second parallel in Canon I is a good example, with Mt §11E, Mk §4E, and Lk §10E being placed in parallel to Jn §6E, and then repeated for Jn §12E, 14E, and 28E. In Canon IX (Lk–Jn), with Luke rather than Matthew serving as his baseline, Eusebius took this approach to an extreme, using only eight discrete passages from Luke, but repeating them alongside various passages from John to produce the twenty-one parallels included in the table. Five of these Lukan passages in fact are repeated three times each (Lk §274E, 303E, 307E, 312E, 341E). For example, both Luke and John record three statements made by Pilate about Jesus’ innocence (Lk 23:4, 14, 22; Jn 18:38, 19:4, 6), and one would expect each of the three Lukan passages to be aligned in sequence with the three Johannine passages, producing three parallels between these two gospels. Eusebius, however, repeated all three Johannine passages (Jn §182E, 186E, 190E) alongside each of the Lukan passages (Lk §303E, 307E, 312E), turning these three parallels into nine and giving the impression of more Luke–John parallels than there actually are. The Syriac reviser, recognizing this superfluity, removed the excess by reducing all but one of these repeated parallels in Canon IX.49 For example, statements of innocence one, two, and three from Pilate are now, in the new system, aligned with one another across Luke and John as Lk §349S, Jn §206S; Lk §354S, Jn §210S; and Lk §359S, Jn §214S.

Of the new parallels added to Canon IX, some are in fact only more precise subdivisions of parallels Eusebius had already noted. For example, Eusebius had treated the great catch of fish in Luke 5:4–7 (=Lk §30E) as one large block parallel to two portions of the Johannine great catch of fish (Jn 21:1–6, 11 = Jn §219E, 222E). The Syriac, however, divides the chunk of Lukan text into four sections (Lk §36S–39S), now placed alongside three Johannine sections (Jn §256S, 257S, 261S), to produce three Canon IX parallels in place of Eusebius’ original two. There are also genuinely new parallels in Canon IX that Eusebius had previously failed to take note of. The two that stand out most clearly are the fact that both Luke and John report that Jesus’ tomb was previously unused (Lk 23:53d; Jn 19:41c = Lk §382S; Jn §239S) and that both evangelists also uniquely report Peter’s visit to the empty tomb (Lk 24:12; Jn 20:6–10 = Lk §392S; Jn §242S). The former parallel Eusebius had included as a part of a larger Canon I parallel, even though only Luke and John present this detail, and the latter two passages about Peter’s actions on Easter morning he had included in their respective Canon X tables (Lk §339E; Jn §210E). Hence, even though the total number of passages listed in Canon IX decreases in the Peshitta revision, it nevertheless forges new links between these two gospels, and thereby presents the reader with information that was previously unaccounted for in the Eusebian original.

Canon XMt

Canon X passages should be the least complicated to create, given that they do not require coordination across multiple gospels but simply the identification of unique material that was previously a part of a larger passage in another Canon. One exemplary passage is Matthew 5:14–16, a dominical saying that occurs in Matthew and Luke. Eusebius treated these three verses together as a section, placed in Canon Table II with the following parallels:

| Mt §32E | Mk §39E | Lk §79E |

|---|---|---|

| Mt 5:14 You are the light of the world. A city built on a hill cannot be hid. Mt 5:15 No one after lighting a lamp puts it under the bushel basket, but on the lampstand, and it gives light to all in the house. Mt 5:16 In the same way, let your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father in heaven. | Mk 4:21 He said to them, ‘Is a lamp brought in to be put under the bushel basket, or under the bed, and not on the lampstand?’ | Lk 8:16 No one after lighting a lamp hides it under a jar, or puts it under a bed, but puts it on a lampstand, so that those who enter may see the light. |

The Syriac retains these parallels, but significantly pares down the Matthean passage, dividing it into three sections. Matthew 5:14 and 5:16 (Mt §41S, 43S) now are assigned to Canon XMt, while only Matthew 5:15 (Mt §42S) is retained in the Canon II parallel (along with Mk §51S and Lk §99S), obviously because it is the portion of the original with the closest similarity to the other two passages, since it speaks of a ‘lamp’. In contrast, the metaphor of a ‘city’ in Matthew 5:14 and the command to ‘let your light shine’ in Matthew 5:16 are unique to Matthew.

Canon XMk

Because so much of Mark is shared by Matthew and Luke, Canon XMk is perhaps the most difficult table to add to. Eusebius had already done a good job of identifying most of the unique Markan passages, but the Peshitta reviser managed to highlight several more, mostly by sectioning off short sentences from larger passages that are shared across the Synoptics. For example, Eusebius had created the following Canon VI parallel:

| Mt §152E | Mk §68E |

|---|---|

| Mt 14:32 When they got into the boat, the wind ceased. Mt 14:33 And those in the boat worshiped him, saying, ‘Truly you are the Son of God’. Mt 14:34 When they had crossed over, they came to land at Gennesaret. | Mk 6:51 Then he got into the boat with them and the wind ceased. And they were utterly astounded, Mk 6:52 for they did not understand about the loaves, but their hearts were hardened. Mk 6:53 When they had crossed over, they came to land at Gennesaret and moored the boat. |

As can be seen, the opening and closing of these two passages are nearly identical, though the middle verse in each presents two very different reactions from the disciples. The Peshitta version of Eusebius’ system therefore keeps the opening and closing of the Markan passage aligned with the two halves of the Matthean text as two separate Canon VI parallels (Mt §183S, Mk §87S; Mt §184S, Mk §89S), and creates a new Canon XMk section for the middle verse of the Markan passage that is unique (Mk §88S).

Canon XLk

With respect to Canon XLk we should first observe a peculiarity in the Peshitta revision of Eusebius’ paratext. Luke’s dedicatory preface to Theophilus (Lk. 1:1–4) should belong in this table because it is unique to the third gospel, as indeed Eusebius had done (Lk §1E). The Syriac, however, begins Lk §1S not at Luke 1:1 but instead at Luke 1:5 (see fol. 143v of the Rabbula Gospels). As a result, the opening four verses of the gospel are unnumbered, and therefore not represented in any of the ten Canons. The only other gospel to begin with a Canon X section is Matthew, and here also the reviser began Mt §1S not at Matthew 1:1, but at Matthew 1:2. Perhaps the scribe regarded both passages as prefaces and so separate from the body of the text.

Despite the overall increase in the number of sections in this Canon, the Syriac reviser also removed two sections from the table in order to correct inconsistencies in Eusebius’ original design. I pointed out in chapter 2 that, according to the logic of Eusebius’ system, there should never be two Canon X sections in sequence in any gospel, because a new section is only supposed to begin where the text changes to a different relational category. Nevertheless, twice in the Gospel of Luke back-to-back Canon XLk passages occur: Luke §67E–68E (=Lk 7:11–16, 17) and §163E–164E (=Lk 13:1–5, 6–13). In the Peshitta version of Luke, each of these pairs of sections is collapsed into one (Lk §85S, 191S), resolving the inconsistency in the rationale for the sectioning of the text. As with the previous two Canon X tables, the new additions to Canon XLk mostly arise from breaking off details in Luke’s version of events or sayings from larger sections of parallel passages. For example, Eusebius had created a Canon I parallel for the verses from each gospel in which Jesus took bread, blessed it, and identified it with his body (Mt 26:26; Mk 14:22; Lk 22:19; Jn 6:35a, 48, 51, 55 = Mt §284E; Mk §165E; Lk §266E; Jn §55E, 63E, 65E, 67E). However, across these various passages, Luke alone records the dominical command ‘Do this in remembrance of me’. The Peshitta version therefore isolates this short sentence from the larger passage in order to create a new Canon XLk section (Lk §304S), thereby highlighting Luke’s distinctive contribution to the accounts of the last supper and the origins of the eucharistic ritual. Similarly, although all three Synoptics record Judas’ greeting of Jesus with a kiss on the night of his betrayal (Mt 26:48–50; Mk 14:44–6; Lk 22:47b–48 = Mt §301E; Mk §182E; Lk §286E), only Luke records that Jesus rhetorically asked Judas, ‘Is it with a kiss that you are betraying the Son of Man?’ (Lk 22:48). Accordingly, the Peshitta breaks this verse off from a larger Canon II section in order to make it a new Canon XLk section (Lk §328S).

Canon XJn

In Canon XJn we observe one of the very few mistakes in the revised version of Eusebius’ paratext. The fourth gospel uniquely records the wedding at Cana at which Jesus turned water into wine (Jn 2:1–11), so Eusebius placed this passage in Canon XJn along with the immediately preceding verses (1:43–51) to create one large section of unique material (Jn §18E). I noted above that the Syriac reviser excerpted a portion of this large block of text, specifically John 1:49–51, in order to align Nathanael’s confession of Christ with similar confessions across the gospels. One would expect that, after the conclusion of the exchange between Nathanael and Jesus, the Peshitta would revert back to a Canon XJn passage for the wedding at Cana episode. In fact, however, the section that begins at John 1:49 extends all the way through 2:11, and so is placed in parallel with the confessions of Peter, Andrew, and others, even though it is difficult to see how the wedding at Cana presents a similarity with these other passages. The most likely explanation for this oddity is that the Syriac reviser meant to stop his new section at John 2:1, in order to isolate only Nathanael’s confession for the purpose of his new Canon I parallel, but has mistakenly carried on the section until the break in the text that Eusebius had originally created at 2:11. Despite this evident mistake, it is also the case that the Syriac reviser once again corrected an inconsistency in Eusebius’ system. Another pair of back-to-back Canon X passages occurred at John 7:33 and 7:34–9 (=Jn §80E, 81E). In this instance, rather than collapse them together, the Syriac reviser found parallels in Matthew and Mark for the first passage, thereby moving it into Canon IV (Mt §326S; Mk §191S; Jn §90S = Mt 26:11b; Mk 14:7b; Jn 7:33).50 Perhaps these were even the passages that Eusebius had in mind when he originally made John 7:33 a distinct section, though for whatever reason it ended up in Canon X in his system rather than Canon IV.

In the immediately preceding example, the Syriac reviser made a change that resulted in the loss of one Canon XJn passage. In another instance, it appears that he again was perhaps correcting Eusebius and in so doing added a new passage to Canon XJn. The dominical promise that a prayerful request made in faith and in the name of Jesus will be granted occurs in Matthew, Mark, and John, though in Matthew and Mark it occurs in the midst of the episode of the cursing of the fig tree (Mt 21:22; Mk 11:24), while in John it is integrated into the farewell discourse in the upper room (Jn 14:13–14). Eusebius made these passages a Canon IV parallel (Mt §216E; Mk §125E; Jn §128E), but inexplicably carried on the Johannine section to include John 14:15–21 as well, even though these verses are unrelated to the Matthean and Markan passages. The Peshitta revision preserves this Canon IV parallel (Mt §259S; Mk §150S; Jn §151S), but correctly makes a break after John 14:14, with the result that John 14:15–21 becomes a new Canon X section (Jn §152S). Another new Canon X section occurs at John 19:5. Eusebius had presented this verse (Jn §187E) in Canon IV in parallel with Matthew 27:27–9 and Mark 15:16–19 (= Mt §329E; Mk §207E), presumably because all three passages make mention of Jesus’ crown of thorns and purple robe. However, the scenes in Matthew and Mark describe the mockery of Jesus by the soldiers in the praetorium, while John 19:5 concerns Pilate’s presentation of Jesus to the crowd with the famous declaration, ‘Behold the man!’ The latter scene occurs only in the fourth gospel, and the Syriac reviser, recognizing this, shifted John 19:5 (= Jn §211S) from Canon IV to Canon XJn.

Conclusion

The above examples are representative of the kinds of changes that were made throughout Eusebius’ system by the Syriac scribe. Notably these alterations are not isolated to a single gospel, or to individual parts of various gospels, or only to certain Canons, which suggests that this unnamed person undertook a systematic revision of the entirety of the paratext he found in his Greek exemplar. Given the requirements of this task, he must have engaged in the most thorough study of the similarities and differences amongst the gospels since Eusebius himself. Although he seemingly did not set about interpreting the passages and formulating a theory about gospel writing, as had Augustine, the Syriac reviser stands in continuity with Ammonius and Eusebius in using the methodology of demarcating sections of text for the purpose of comparative analysis. For the most part, his revision represents an upgrade of Eusebius’ original, resulting in an even more powerful reference tool for later users to employ. Though we can recover the rationale behind the revision only through inference, the kind of reasoning it implies is not fundamentally different from that of the Irish exegetes we will consider in the next chapter who set about classifying parallels in different kinds of relational categories. Because the four gospels present varying kinds of parallels with a range of types of similarities, this process of analysing related passages can never be complete but always remains open to debate and alternative resolution. What is unique about the Syriac tradition is that this scholarly investigation resulted in a completely revised version of the original Eusebian paratext. Future studies of the transmission of the apparatus in other languages might reveal isolated editorial interventions undertaken for similar reasons, but such a thorough overhaul of the original has not survived in any other tradition.

It is also striking that the difficult and tedious labour that must have been required to produce the Peshitta Canon Tables does not appear to have been driven by any polemical motivation. The parallels the Syriac scribe revised and the new ones he created reveal no theological or exegetical agenda. The closest we can come to isolating a contextual factor that might have given impetus to this project is the fact that Syriac-speaking Christians continued to use Tatian’s gospel text well into the fifth century, at least according to the report of Theodoret. Syriac scribes accustomed to copying the ‘Gospel of the Mixed’ as well as the ‘Gospel of the Separated’ must have had a greater awareness of the interrelationships among the four gospels than almost anyone else in the world of late antiquity. Perhaps it was this peculiar situation that motivated the anonymous scribe or scribes to expend the energy required for such a laborious task.

One further fact about this revised version must be mentioned because it is so obvious that it is easy to miss. The person responsible for it ensured that he would for ever remain hidden in Eusebius’ shadow. The Peshitta Letter to Carpianus makes no mention of the fact that the paratextual apparatus that follows is in fact a revised version of Eusebius’ original, but instead presents it as originating with the Caesarean historian himself.51 The result of this silence of the scribe about his own work is that a reader of the Peshitta version of the gospels would have no idea that his edition of the Canon Tables differed from that in the Greek gospel tradition. This authorial self-effacement also meant that the stature of Eusebius would remain high for later users of the Peshitta version.

In fact, some later Syriac sources eventually came to attribute an even more significant role to Eusebius than can be maintained on strictly historical grounds. The eighth-century bishop of Mosul, Moses bar Kepha, in answer to the question ‘who collected the four books of the evangelists and set them in order in one book?’ explains that

some people, indeed, say that Eusebius of Caesarea, when he saw that Julianus of Alexandria made the Gospel of the Diatessaron, i.e. by means of the Four, and changed the sequence of the words of the Gospels, [and also Tatian] the Greek, the heretic made a Gospel, the one that is called Tasaron, and he too changed the sequence of the words, he, Eusebius, took care and collected the four books of the four Evangelists and ordered them and placed them in one book, and preserved the body of the evangelists’ narration as it was, without taking away anything from their narration or adding anything to them, and he made certain Canons concerning their agreement and disagreement with one another.

Bar Kepha’s opening question shows a striking degree of awareness that the fourfold

gospel itself has a history, in his tacit admission that these four texts have not

always sat together between the covers of a single codex. He (or whatever earlier

Syriac source he was drawing upon) probably came to think that Eusebius was responsible

for collecting these four texts together based on the fact that Peshitta gospel codices

began with Eusebius’ prefatory Letter to Carpianus, and, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, it was a small step to attribute

not just the marginal apparatus but the form of the book itself to the Caesarean historian.

Of course, with more evidence at our disposal than bar Kepha had, we now know that

the four-gospel codex came into existence at least half a century before Eusebius’

labours. However, bar Kepha’s claim that Eusebius collected these four narratives into a single  contains a kernel of truth, since, as argued in chapter 1, Eusebius’ Canon Tables were in fact issued as a component of a new edition of the

fourfold gospel, one in which his marginal apparatus both highlighted the canonical

boundary between this collection and any potential rival texts and, also, bound these

four texts together as a united witness to the story of Jesus.

contains a kernel of truth, since, as argued in chapter 1, Eusebius’ Canon Tables were in fact issued as a component of a new edition of the

fourfold gospel, one in which his marginal apparatus both highlighted the canonical

boundary between this collection and any potential rival texts and, also, bound these

four texts together as a united witness to the story of Jesus.

occurs in two of them, in a colophon in the Sinaitic manuscript and as as a title