1788–1812

This Shoshone, whose name means “bird woman,” is of such historical and cultural importance that she was even commemorated by the U.S. Mint in the year 2000, when she was depicted on the dollar coin.

Sacajawea was an icon for the women’s suffrage movement in the early part of the 20th century, and she has featured in films, novels, and songs.

Her adventure began when, at the age of 12, she was kidnapped along with several other young girls from the Lemhi Shoshone tribe, who were living about 20 minutes away from what is now Salmon, Idaho. The kidnappers were a rival tribe of Hidatsa, and the capture itself resulted in the deaths of eight adults and a number of young boys. She was taken to a Hidatsa settlement in North Dakota. A year later, she and another girl, “Otter Woman,” became the wives of a Quebec trapper named Toussaint Charbonneau. There are theories that the girls might have been purchased, or else won as a gambling debt.

By the time she was 16, Sacajawea was carrying Charbonneau’s child; at this time, some explorers arrived in the area. Two of the explorers, Captain Meriwether Lewis and Captain William Clark, needed help for the next stage of their journey up the great Missouri River, a journey that was due to set off in the coming spring. They engaged Charbonneau to act as interpreter when they realized that his young wife also spoke Shoshone. This, they knew, would prove essential, since they would need the help of the tribe. It’s because of Lewis and Clark that we know the exact date that Sacajawea and Charbonneau’s baby was born. Jean Baptiste Charbonneau came into the world on February 11, 1805. The explorers nicknamed him “Pompy” and Sacajawea “Janey.”

The baby was just two months old when the party set off up the Missouri River in shallow open boats. The going was tough and precipitous; Sacajawea’s swift action in rescuing the journals of the two captains when they went overboard was rewarded when they named that part of the river, a tributary of the Musselshell that joins the Missouri, after her.

In fact, although she was able to assist the party in many practical ways during the course of their arduous journey, it was possibly the very presence of Sacajawea, and of her baby, which sealed the success of the mission. It would have been very unusual for a female to be included in such a party, and her appearance acted as an assurance that the mission was a peaceful one.

As chance would have it, the chief of the first Shoshone tribe they came across was Sacajawea’s brother. They had been kidnapped together as children, then separated, so their reunion was warm and affecting. The explorers needed horses for the next part of their journey; the Shoshone agreed to help them with the animals—not only this, but they also agreed to provide guides to lead the party over the daunting Rocky Mountains. Going was tough over the peaks, and the party were close to starvation when they reached the other side; however, Sacajawea was able to locate roots for them to eat. Later, she would trade her blue beaded belt in return for a beautiful warm otter skin robe that Clark desired.

Eventually the party reached the Pacific Ocean and every single member voted that they should construct their winter quarters. Sacajawea, too, was allowed to vote on this.

By July of 1806 the party, on the trip back, had reached the Rocky Mountains once more and were, no doubt, dreading the journey. However, once more Sacajawea surpassed the bounds of what was expected of her. Somehow she knew a pass across the mountains which would make the journey easier. This subsequently became known as Gibbons Pass. Further, a little while later she recommended another shortcut, now named Bozeman Pass—this particular route would become a source of controversy later in the century.

Sacajawea, her husband, and her child were regarded with great affection by Lewis and Clark. Clark referred to the little boy as “my boy ‘Pompy’,” and offered to adopt him, bring him up, and give a home to “Janey,” who would take care of the boy and also his father. Accordingly, the family moved with Clark to St. Louis, Missouri, where they settled. Clark enroled Jean Baptiste in the best school in the area, the Saint Louis Academy boarding school.

Sacajawea had another child, a daughter named Lizette, some time after 1810. Bear in mind that she was still only just 22. When she was 24 or 25, Sacajawea is believed to have died—like so many Native Americans, of an unknown illness. Clark became the legal guardian of both Jean Baptiste and Lizette in 1813.

There’s a question mark around the supposed death of Sacajawea. An oral tradition relates a different story about her. The tale goes that she left her husband in 1812 and, after a journey across the Great Plains, married a Comanche. Later, it was rumored that she returned to Wyoming, where she died in 1884.

This story was investigated in 1925 by a Dr. Charles Eastman, who was of Sioux origin. The doctor had been hired by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to try to ascertain the truth about the date of Sacajawea’s death. After speaking to many elderly people who had memories of the time, he heard talk of a woman named Porivo (meaning “Chief Woman”), a Shoshone, who had told of a long journey she’d taken in aid of the white men; she also was alleged to have owned a peace medal that was contemporary with the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Eastman also came into contact with a Comanche woman who claimed that Porivo had been her grandmother; Porivo had married a Comanche called Jerk Meat. Her two sons—named Bazil and Baptiste—could speak English and French. All this makes sense if Porivo was indeed Sacajawea; in which case, she must have lived to be considerably older than 24, having died in 1884.

A monument was erected in Wyoming in 1963 in support of the Porivo/Sacajawea story, but it’s likely that the definitive truth will never be discovered.

Where a territory held a number of tribes that were allied to one another, and where each of those tribes had a chief, the sachem was the designated chief of all those tribes—i.e., the chief of the chiefs. Originally the role of sachem applied only to the tribes of Massachusetts, but the term is used by other Native American peoples as well.

One of the important Cheyenne myths describes how the creator, Maheo, gave a great gift to the Nation, which he placed in the hands of the hero prophet, Sweet Medicine.

This gift was four arrows, sacred objects, also known as Mahootse; two of the arrows stood for war, and the other two for hunting. The arrows were treasured for many generations as a symbol of the spirit of the tribe itself. They were kept in a tipi named the Sacred Arrow Lodge, which was guarded by a Cheyenne society of men called the Arrow Keepers.

The Arrow Renewal Ceremony was carried out once a year. Lasting for four days, Cheyenne clans and bands came from far and wide to celebrate the rituals in which the Sacred Arrows were renewed and blessed. Sometimes the arrows themselves were carried into battle.

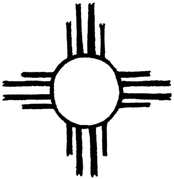

See Medicine Wheel

An important instrument of protection in times of war, the sacred shield would often be painted with totems and other magical symbols which, it was hoped, would invoke the protective powers of the gods to aid the owner of the shield.

Once the Native Americans had adopted the horse, some peoples also felt the necessity to design saddles, although most had the ability to ride bareback, both in battle and in hunting buffalo.

In general there were two types of saddle: the frame saddle, and the pad saddle.

The frame saddle was preferred by peoples that included the Shoshone, Ute, and Crow. Made from flexible cottonwood, the frame was both given shape by and covered with rawhide, applied when “green,” which shrank as it dried to make a shaped, tough saddle. The frame saddle had a pommel at the front and back so that the rider could hang on. Although this saddle has similarities to those used by the Spanish conquistadors, it is likely that it was designed without any outside assistance and without influence from the Spanish. A different sort of frame saddle was made for use by the Arapaho, Assiniboin, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Comanche, Cree, Dakota, and Mandan, again using “green” rawhide and featuring a pommel over which a lariat or lasso could be draped.

The pad saddle was a less sophisticated piece of equipment, a sort of cushion made from a softer hide, stuffed with grasses and hair, with a stirrup hanging from either side. The pad saddle was simply tied underneath the horse. The pad saddle was useful in horse raids, since several of them could be carried without being stuffed, and were then filled and fitted to the stolen horse, which could then be ridden away.

An Algonquian term, the sagamore is the name used for the chief of a tribe which is part of a confederation of other tribes. The sagamores of the tribes were, in turn, led by the sachem.

A large cactus which grows in the southwest. Its fruits are eaten by several Native American peoples, including the Pima.

A sagamore, or chief, of the Pemaquid/Abenaki people who had apparently learned English from some fishermen, Samoset was the first Native to greet the Pilgrim Fathers in 1620 when they landed on Cape Cod. We can only imagine the element of surprise that these early visitors to America experienced, having traveled halfway around the world, when they were greeted with the words “Welcome, Englishmen!”

Samoset helped to facilitate the first ever land “deal” between the Natives and the settlers, deeding some 12,000 acres of his people’s land to a man named John Brown. He also introduced the English to his chief, Massasoit.

A division of the Dakota/Lakota Sioux. Their own name for themselves was Hazipco or Itazipcloa, meaning “the people who hunt without bows.” Sans Arc is the French translation of that name. They formed part of a larger group called the Central Dakota/Lakota. Joining them in this particular group were the Two Kettles and the Miniconjou.

Several illustrious leaders were born into the Sans Arc clan, including Yellow Hawk and Spotted Eagle.

One of the four divisions of the Lakota/Dakota Sioux. The others in this group were the Teton, Eastern Sioux, and the Yankton. They originally lived in the area of the town now named after them: Santee, South Carolina. They spoke Catawba, which was a part of the Siouxan language family.

The name Santee means “from south of the river,” which refers to the river that has the same name as the tribe. The tribe had an unusual funerary practice in that they placed their dead on the top of high mounds—the taller the mound, the more important the deceased person had been in life. The corpse was then protected with a wooden pole construction, decorated with feathers and rattles. The bones of the dead were collected and kept carefully in a special box, and oiled every year.

The last sachem, or chief, of the Pequot, who were virtually obliterated in the Pequot War of 1636.

“A long time ago this land belonged to our fathers, but when I go up to the river I see camps of soldiers on its banks. These soldiers cut down my timber, they kill my buffalo and when I see that, my heart feels like bursting.”

1820(?)–1878

Kiowa warrior chief Satanta was known to his people as “White Bear Person.” He came to prominence during the wars of the 1860s and 1870s, known as the “Orator of the Plains” because of his skills in speaking. He was also involved in negotiating various treaties with the American Government, including the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867 which stated that the Kiowa would have lands set aside for them over which they would rule. When the white settlers and explorers continued to trespass on this tribal land, unsurprisingly the Kiowa retaliated by raiding the new settlements and causing problems for the white men. The situation deteriorated even further when the old chief, Dohosan, died in the mid-1860s and other would-be chiefs battled with one another for supremacy. Satanta, whose reputation as both a good leader and an effective warrior was growing, was among these men. Meanwhile, the trouble between the Kiowa and the white settlers was getting more bloody, with casualties on both sides; in one incident, a settler named James Boz was slaughtered and his wife and children ransomed to the Army; another incident saw the death of a young Kiowa avenged by a Kiowa attack which resulted in a retaliatory force of cavalry killing several Kiowa children.

The Medicine Lodge Treaty, signed in 1867, did not, as expected, provide any resolution to the troubles, and so General Philip Sheridan was called out to restore order before matters escalated any further. Sheridan employed the harsh tactic of destroying the homes and horses of the tribespeople; his Lieutenant, George Custer, had no compunction about killing women and children. Satanta and another chief, Guipago, decided the only option was to surrender. Approaching the troops flying the white flag, the two chiefs were arrested and imprisoned pending the hanging that Custer fought for. However, the Kiowa promised that they would cease attacking the European settlers in return for Satanta’s release.

Once liberated, Satanta and his band started to attack the wagon trains crossing their territory. In one of these attacks, seven white men were killed. Satanta was among those imprisoned. Satanta warned the guards that if he were executed, the consequences would be terrible since the Kiowa would raise the level of their attacks even further. After a trial, Satanta was sentenced to death, but this was commuted. He was released in 1873.

The peace didn’t last long: a year after his release, Satanta was leading attacks once more, and a few months later, in October 1874, found himself again imprisoned and facing a life sentence. Rather than endure this prospect, Satanta killed himself by throwing himself from a high window. He died on October 11, 1878.

The Sauk and Fox peoples, members of the Algonquian tribe, were so closely aligned that they tend to be grouped together—despite the fact that the Sauk were known in their own language as the “yellow earth people,” while the Fox were called the “red earth people.” The similarities between the two encompassed both language and customs. Both were woodland Indians, living in homes made of birch bark, and using canoes made of the same material. Skilled farmers, they grew squash, maize, and beans, supplementing their diet with wild rice. They also cultivated tobacco. The appearance of both tribes was similar, too: the upper part of their bodies were kept bare, while the lower half they covered with leggings and moccasins. The hairstyle of both was also distinctive: a tuft of hair running from the front of the forehead to the nape of the neck with the rest shaved bald.

The Sauk and Fox tribes originated in the area of the Great Lakes and later moved to Kansas and Iowa, forming a federation in 1760. They also fought side by side in the Black Hawk War of 1832. The warriors in this conflict were identified by an imprint in white paint of a hand across their shoulders.

A Jesuit priest of the time, Father Allouez, described the Sauk and Fox as the most savage of all the woodland tribes, saying that they would slaughter a white man simply because they didn’t like the look of his whiskers. Both tribes liked to fight, as evidenced by their continual skirmishes with the French as well as with the Ojibwe.

1707(?)–1786

A member of the Seneca who were a part of the all-powerful Iroquois Confederacy, Sayenqueraghta was the son of a chief of the Turtle clan of the Seneca, in the western part of New York state. In 1751 he was designated war chief. Because his official position was smoke-bearer, he was often called “Old Smoke.”

In the early days of the American Revolutionary War, Old Smoke did his best to keep the Iroquois in a neutral position. In 1777 he tried to dissuade Seneca warriors who had elected to join forces with the British. But then, in the same year, Old Smoke decided to fight alongside the British after all; it was at this point that he was named as a war chief, as was his Seneca compatriot, Cornplanter.

Old Smoke had a heavy price to pay during his military career. He was one of the organizers of an ambush in which his son was killed; the village named after him was razed to the ground. He relocated to the Buffalo Creek Reservation in New York State and after the war, in recognition of his courage, the British Government settled on him a military pension of $100 a year. Accounts from the time relate that Old Smoke had succumbed to the “fire water” of the white man; in this he was not alone.

Old Smoke died in 1786.

A protective form of armor made of many small, hard discs linked together. These discs might be made of stiffened buffalo hide. Scalemail would be worn underneath normal clothes so that the enemy would not realize it was being worn.

Scalemail was for the most part impervious to arrows, spear tips, and even musket shot.

Essentially a celebration of victory in battle, the scalp dance uses the scalps of the enemy not only as a token of this victory but as a sacred ritual and a way of laying the spirits of the deceased to rest; the dance also expresses mourning for dead tribal members.

The drumming and music for the scalp dance was provided by the men of the tribe, while the dancing was performed by the women, young and old.

The women would dance around the scalps in concentric circles, singing at the same time. The scalps themselves could be attached to the women’s clothing, or else were attached to poles stuck into the ground, decorated with feathers, beads, ribbons, and streamers. Any woman whose son, husband, or brother had been killed by one of the men scalped could choose to tell the story of his death, after which the dance continued.

It’s true to say that scalping is most commonly known as a Native American practice. However, it’s not strictly confined to one part of the world at all, nor was it ever carried out universally among Native peoples. Not only is it mentioned in the Bible, but Herodotus wrote of it in 440 in relation to the Scythians. There is also evidence that it was performed by the Visigoths and the Anglo-Saxons, the Slavs, and the Persians.

By any account, scalping is a gruesome practice, which can be carried out equally effectively on a living person or a corpse. Here is a description of a scalping, written by a French soldier who is known only by his initials, J.C.B. This soldier fought in the French and Indian War between 1754 and 1760, and his account is a graphic one:

“When a war party has captured one or more prisoners that cannot be taken away, it is the usual custom to kill them by breaking their heads with the blows of a tomahawk … When he has struck two or three blows, the savage quickly seizes his knife, and makes an incision around the hair from the upper part of the forehead to the back of the neck. Then he puts his foot on the shoulder of the victim, whom he has turned over face down, and pulls the hair off with both hands, from back to front … This hasty operation is no sooner finished than the savage fastens the scalp to his belt and goes on his way. This method is only used when the prisoner cannot follow his captor; or when the Indian is pursued … He quickly takes the scalp, gives the deathcry, and flees at top speed. Savages always announce their valor by a deathcry, when they have taken a scalp … When a savage has taken a scalp, and is not afraid he is being pursued, he stops and scrapes the skin to remove the blood and fibers on it. He makes a hoop of green wood, stretches the skin over it like a tambourine, and puts it in the sun to dry a little. The skin is painted red, and the hair on the outside combed. When prepared, the scalp is fastened to the end of a long stick, and carried on his shoulder in triumph to the village or place where he wants to put it. But as he nears each place on his way, he gives as many cries as he has scalps to announce his arrival and show his bravery. Sometimes as many as 15 scalps are fastened on the same stick. When there are too many for one stick, they decorate several sticks with the scalps.”

The scalp was effective proof of victory over an enemy, and although it was possible to survive such treatment, it wasn’t likely that a victim would live to tell the tale. And the authorities actually encouraged scalping for this reason. Both sides embraced this barbaric practice, as underlined by the British Scalp Proclamation of 1756, issued by Governor Charles Lawrence of Nova Scotia:

“And, we do hereby promise, by and with the advice and consent of His Majesty’s Council, a reward of £30 for every male Indian Prisoner, above the age of 16 years, brought in alive; or for a scalp of such male Indian £25, and £25 for every Indian woman or child brought in alive: Such rewards to be paid by the Officer commanding at any of His Majesty’s Forts in this Province, immediately on receiving the Prisoners or Scalps above mentioned, according to the intent and meaning of this Proclamation.”

This wasn’t the only such treaty that conclusively supported the slaughter of the Natives whose territory the Europeans were effectively stealing. Earlier, during Queen Anne’s War, $60 was offered for scalps by the Massachusetts Bay Colony. And, in 1744, the Governor of Massachusetts, William Shirley, issued a bounty for the scalps, not only of Indian men, but of women and children, too. In 1749 the British governor, Edward Cornwallis, guaranteed payment for scalps taken from any Indians, no matter their age or sex. In 1755 Governor Phips of the Massachusetts Bay Colony was paying $40 for the scalp of an Indian male, and half that amount for women or children under the age of 12.

Both Native Americans and white men could act as scouts, either for the Army or for pioneers who were looking for friendly territory where they might settle. Some of the best-known white scouts included Buffalo Bill Cody and Kit Carson, whereas, notably, the Pawnee tribe provided a large number of Native scouts to the Army. The Pawnee were proud of the fact that it had never been at war with the white men. The Pawnee wore regular Army uniforms when they were on parade, but preferred to be virtually naked when they were carrying out their scouting work. Pawnee scouts were awarded many honors and medals for their invaluable work in the Indian Wars which took place between 1865 and 1885.

In common with other societies throughout the world, secret or closed organizations and societies were an important part of Native American society. Many of these societies—such as the Midewiwin—had to do with healing and magic; the Buffalo Society, for example, was dedicated to curing illnesses. Others included military societies, soldier societies, and warrior societies. Other secret societies kept records of the tribe, including myths and legends as well as historic events.

The head of one of the ceremonial societies had the same status as a priest; this shaman or medicine man would have the power to mediate between the worlds of spirit and matter for the benefit of the tribe. The Big-bellied Men Society of the Cheyenne were party to the secrets of walking on fire or hot coals with bare feet.

Certain secret societies are open to all members of a particular tribe; everyone else, however, is excluded.

In the context of Native American peoples, this word describes a “settled” tribe in which the people live in permanent villages, as opposed to the purely nomadic peoples. Because of their settled status, sedentary tribes were able to farm their land.

Belonging to the Muskhogean language family, the Seminole’s original stamping ground was the southern part of Georgia and Alabama, and, later, the northern part of Florida. They were forced into the swampy Everglades area after a series of three tempestuous wars with the white settlers. The Seminole of Florida still call themselves “The Unconquered People.”

Prior to being renamed as Seminole (whose name is a corruption of a Spanish word meaning “runaways”) in the 1770s, these Native Americans were part of the Creek tribes. Indeed, several African slaves—called the Black Seminoles—swelled the numbers of the tribe. Some were escapees, some had been freed, and their presence would cause problems later on.

Relationships between the Seminole and the white settlers were becoming more and more uncomfortable as the Europeans moved further and further into Indian lands. In 1817 the first of the three Seminole wars erupted when U.S. Army troops, under the auspices of President Andrew Jackson, invaded Seminole territory in Florida and defeated the tribe, killing at least 300. The tribe had been accused, also, of harboring escaped slaves. The survivors fled into the swampland areas.

The Indian Removal Act saw the Government try to remove the tribe to the Indian Territory in Oklahoma in 1834. This caused the outbreak of the Second Seminole War, which lasted some eight years, during which time the tribes successfully held off the American troops. Initially the Seminole, under their chief Osceola, won some significant battles, but then Osceola was captured when he went to meet with the Americans with the aim of bringing about peace. The remaining Seminole were corralled and forced to relocate to Oklahoma. Some of the tribe remained hidden in the Everglades. Subsequently, they would be assigned reservations in this area.

The largest of the five tribes that formed the historically important Haudenosaunee, also known as the Iroquois Confederacy. The other four tribes that originally belonged to this alliance were the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, and Onondaga, with the Tuscarora becoming the sixth member some years after the organization was founded.

When the Confederacy was founded, the Seneca lived on the lands from the Genesee River to the Canandaigua Lake in western New York State. The tribe lived along the river in longhouses. Because of their geographical location, within the Haudenosaunee the Seneca were designated “Keepers of the Western Door.”

The year 1142 has been pinpointed as the one in which the Seneca joined the Confederacy; oral accounts relate that there was a solar eclipse in the same year, hence the date can be calculated reasonably accurately. The Seneca creation myth relates that the Seneca emerged onto the earth from a great mound, and their autonym (a tribe’s name for itself) reflects this: Onondowaga means “People of the Great Hill.” The Onondaga Nation share exactly the same name, and the same myth.

A nation of farmers, the Seneca were skilled agriculturalists, growing the mutually beneficial Deohako or “Three Sisters” crops of beans, squash, and corn. The harvest was supplemented by fishing and hunting. The Seneca were also able builders, and constructed fortifications from wooden stakes around their village settlements. While it was primarily the men of the Seneca people who hunted, the women tended the crops and also gathered wild plants, nuts, and berries, both to eat and to use as medicine. Women were in charge of the smaller clan units and decided who would be the tribal leader.

The first colonists found that the Seneca men were highly tattooed, and wore their hair in the Mohawk fashion—that is, with a tuft running from the forehead to the nape of the neck, flanked by shaven sides. The tribe became involved in the fur trade, initially with the Dutch and then with other Europeans, including the English. From the Dutch the tribe got guns, which served to enhance their reputation for warlike ferocity.

Their traditional enemies were the Huron; taking advantage of this fact, the French settlers banded with the Huron against the Iroquois. This war started in 1609 and raged on for some 40 years; the power of the Confederacy, though, grew stronger through repeated attacks, and the French/Huron allegiance was finally quashed in 1648. Weakened by disease as well as decades of fighting, the Huron swore allegiance with the Seneca. Their power proven conclusively, the Iroquois Confederacy proceeded to attack and defeat all the surrounding tribes; systematically they trounced the Neutrals and the Erie who, like the Huron, were subjugated and forced to live on the Seneca territory while the Seneca themselves took over the tribes’ former lands. However, a further French attack in 1685 saw many Seneca villages sacked, and the tribe were pushed further down the Susquehanna River.

Meanwhile, the Seneca allegiance with the British and the Dutch gained strength. The tribe did their best to remain neutral when war broke out between the colonists and the British Government; however, when innocent Seneca were killed by the colonists during a battle at Fort Stanwix, the tribe aligned themselves with the British during the Revolutionary War.

Realizing the power of the Iroquois Confederacy, General George Washington deliberately pinpointed the Seneca for a large attack, and sent some 5,000 troops in to defeat the tribe; from this point, they relocated to new villages and settlements along various rivers in the western part of New York State. These settlements became Seneca reservations after the Revolutionary War.

In 1794 the Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, including the Seneca, signed the Treaty of Canandaigua, intended to bring peace both to the Haudenosaunee and the new United States Government. Three years later the reservations were appointed officially, and yet more Seneca lands were sold to the settlers. A further treaty, the Treaty of Buffalo Creek, was signed by Seneca chiefs in 1848; this stipulated that the tribe were to relocate once more, this time to Missouri. However, the majority of the tribe simply refused to go, and in the same year they instead formed their own government, the Seneca Nation of Indians, which is still in existence today.

c.1760–1843

One of the most significant developments for the Native Americans in general, and for the Cherokee Nation in particular, was the construction of an alphabet so that the Cherokee language, previously only a spoken language, could be written down. The story of the person who devised this method of communication reads like a movie script. The giant redwood trees called Sequoias are named in honor of this ingenious person.

Sequoyah was of mixed race. Born in Tuskegee on the Tennessee River to a Cherokee mother (Wu Teh) and an English fur trader, Nathanial Guest (sometimes spelled Gist or Guess), because the Cherokee were a matrilineal people, Sequoyah (or George Gist, as he was named at birth) was raised as such. The name Sequoyah, meaning “pig’s foot,” was given to him either because of an injury or because of a disability affecting his foot. Whichever it was, he was rendered unable to hunt and so he pursued a career as a blacksmith and silversmith.

We know that Sequoyah married at least twice, and it’s also possible that he might have had other wives, since the tribe were polygamous. His first wife was named Sally Waters, with whom he had four children. At some point before 1809, Sequoyah moved to Willstown, in what is now Alabama, setting himself up as a silversmith. He also fought on the side of the United States, under General Andrew Jackson, in the 1812 war against the Creek Nation and the British.

Because of his trade as a silversmith, Sequoyah had dealings with the white settlers and became intrigued by a skill that they possessed: that of writing. This method of communicating by making marks on paper he called, “talking leaves.” He started working on a system of writing that would apply to the Cherokee language, and is said to have neglected everything in order to pursue what became an obsession. His friends and family deduced that he had gone mad; allegedly his wife, suspicious of his work, which she regarded as some kind of black magic, burned his early efforts.

Sequoyah’s interest must have been further fueled by the 1812 war, since the white soldiers were able to read orders and also send and receive letters home, assets that the Native Americans did not have at their disposal.

Eventually, Sequoyah realized that his efforts to make a shape for every word was never going to work, and he broke the Cherokee language down into syllables instead. Progress became much faster, and within a month he had defined 86 characters, some of which were copied from a Latin spelling book that had come into his possession, although he used the symbols in a way which had nothing to do with their origins.

His daughter Ayoka proved a major help in his efforts after he taught her his method, since no adults were taking his efforts seriously. The “alphabet” that Sequoyah was developing is called a “syllabary.” He tried to convince some Cherokee in Arkansas that the syllabary was valid. Initially, they were skeptical, so Sequoyah had each of them say a word while Ayoka was out of the room. He wrote down the words, and then Akoya was able to read them out when she came back in. This was enough to convince these Cherokee of the usefulness of learning the system. Sequoyah spent months teaching, and the final test called for each student to both dictate and write a letter. And it worked. Sequoyah took home a sealed envelope that contained a written speech given by the Arkansas Cherokee leader. He unsealed the envelope and read the speech to his people.

After this the syllabary spreadlike wildfire, and missionaries helped to teach the method, too. Sequoyah was awarded a silver medal by the Cherokee National Council, and subsequently a payment of $300 per year, which continued to be paid to his wife after he died. Because of the syllabary, the Bible and other religious tracts were translated, along with books and legal documents. And the first Indian newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix, was founded in 1828.

In the same year, Sequoyah moved to the Indian Territory in Oklahoma as part of the Indian Removal Act. He became very actively involved in the politics of his tribe and spent the rest of his life negotiating on behalf of his people. He was also keen to develop a language system that would serve as a universal language for all Native Americans. Sadly this was never completed; Sequoyah died during a trip to Mexico, and he is believed to have been buried somewhere along the Mexican–Texas border.

In 1863, beneath a great elm tree in the Lenape village of Shackamaxon, a peace treaty was signed between William Penn, a white settler, and Tamanend, a chief of the Turtle clan of the Lenni Lenape tribe. Penn spoke in the Algonquian language and spoke the following words underneath the tree:

“We meet on the broad pathway of good faith and good-will; no advantage shall be taken on either side, but all shall be openness and love. We are the same as if one man’s body was to be divided into two parts; we are of one flesh and one blood.”

Tamanend said in reply:

“We will live in love with William Penn and his children as long as the creeks and rivers run, and while the sun, moon, and stars endure.”

This agreement presaged almost 100 years of cooperation and peace between the settlers and the tribe. The tree itself became a symbol of the pact, standing for peace, longevity, and protection.

The actual elm fell in 1810 during a huge storm; subsequently, a monument was erected on the spot where it had stood. At the time the site was a humble timber yard, and the commemorative obelisk languished in a corner of the yard until the land was bought toward the end of the 19th century, and Penn Treaty Park went on to provide a more fitting setting for it.

Another name for the medicine man, the origins of the word shaman are from the Tungusian language; the Tungus were a people of eastern Siberia and it is likely that many of the practices of the Native American medicine man had their origins with the very first human beings, who are believed to have entered North America across the Bering Straits. According to recent DNA analysis, some 95 percent of Native Americans are descended from these people. One of the signs of this provenance is the Mongolian spot. Today, many modern shamanic practitioners source Native American rituals and ceremonies in their work.

Originally, the Shasta lived in California, and are remembered in the names of the Shasta River and Mount Shasta. The tribe lived in permanent villages rather than being nomadic or seminomadic, living in plank houses, using dugout canoes, and having acorns as a staple food. The Shasta divided up their territory into areas in which certain families had the right to hunt, a privilege that was handed down the father’s line. Shasta territory yielded obsidian, the natural glass that made for sharp arrow points; they traded this material for the shells called dentalia that stood in for currency, and also for salt and seaweed.

A peaceable people, the Shasta suffered when the California Gold Rush started in the 1820s, some of them even poisoned, for no reason, by settlers. After they banded with the Takelma against the white settlers in the Rogue River War, the Indian defeat saw the Shasta forced onto reservations, a long way from home, in Oregon. In the 1870s, in common with others, in an attempt to reclaim a sense of identity the Shasta embraced the Ghost Dance Movement.

One of the major tribes of the Algonquian family, in which language the word Shawnee means “Southerner,” the original Shawnee stamping ground was the territory that has become South Carolina, Tennessee, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. They were actually driven from their territory initially by the Iroquois in the middle of the 17th century; they returned only to be driven out again by the European invaders.

The tribe did all they could to resist the encroachment of the white men onto their land. They fought on behalf of the French, who waged a war against the English and/or the colonial Americans for some 40 years beginning in 1795. Thereafter, the Shawnee, under Chief Black Hoof, were on friendlier terms with the Americans. Later a band of hostile Shawnee allied with the Delaware tribes, and, under the influence of a shaman named Tenkswatawa, also known as the Prophet, fought the Americans at the mouth of the Tippecanoe River in Indiana, and lost.

Perhaps the most famous Shawnee leader was Tecumseh. Ironically enough, his brother was Tenkswatawa.

There are four Shawnee groups: the first three are known as the Absentee Shawnee, the Eastern Shawnee, and the Cherokee Shawnee. The Cherokee Shawnee are also called the Loyal Shawnee, who became allied with the Cherokee in 1860 and are called “Loyal” because they fought on the side of the Union Army during the American Civil War. The fourth group is the Shawnee Nation Remnant Band, believed to have been descended from the original Ohio Shawnee.

Shawnee men were fighters and hunters; the women were skilled in all aspects of domestic life: they could build the lodges that were their home, cook, grow vegetables, skin and cure hides, and make baskets and also pottery. Women tended the sick of the tribe and used the secrets of herbal medicine. Fathers taught their sons, and mothers taught their daughters.

For the Shawnee, the universe was presided over by the Supreme Being named Moneto. Moneto would reward those who pleased him, and punish those who annoyed him. The Great Spirit was viewed as a grandmother-type character who was constantly busy weaving a net which, when complete, would be dropped over the world and then drawn back up to the heavens. Those who had lived good lives would be taken in the net to a glorious afterlife; the others would drop back down to earth through the holes, where they would suffer a terrible fate as the world came to an end.

The title for the chief of a tribe.

1845(?)–1923

A member of the Brule Lakota tribe, warrior and medicine man Short Bull had fought at the Battle of Little Big Horn and, with Kicking Bear, had visited Wovoka in Nevada, the leader of the Ghost Dance Movement. Short Bull was instrumental in introducing this ill-fated movement to the Lakota.

The Ghost Dance Movement eventually resulted in an appalling catastrophe, the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890, after which Short Bull was imprisoned at Fort Sheridan, near Chicago. However, Short Bull did not remain imprisoned for long; he was released in 1891 to tour with Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show. This was because the U.S. Government were keen to live down the influence of any existing leaders of the movement.

Consequently, Short Bull toured with Cody’s traveling show for the next two years, touring all across the U.S. and into Europe. In a strange twist, Short Bull was also approached by Thomas Edison to appear in an early film, which used a prototype version of what would become the movie camera. The project he took part in actually reconstructed the events of the massacre at Wounded Knee. Short Bull also helped with the research done by numerous anthropological and ethnographical experts who were interested in Native American culture and history in the early part of the 20th century.

He died in 1923 on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota.

Part of the Numic branch of the Uto-Aztecan language group, the Shoshone fall into three divisions: the northern Shoshone, the eastern Shoshone, and the western Shoshone. Originally they roamed a vast area including western Wyoming, southern and western Montana, northern Utah and Nevada, and southeastern Oregon and Idaho.

Sometimes the Shoshone were referred to as “the Snake Nation”; they had already been given the name of “Snakes” prior to the Lewis and Clark Expedition which “discovered” them in 1805. This expedition was subsequently aided by a young Shoshone woman, Sacajawea. It’s likely that the name came because some of the Shoshone lived along the Snake River in Idaho.

The Shoshone of the North and East had appropriated horses from the Comanche; they hunted buffalo, and lived in tipis as did the Plains Indians. Other Shoshone lived in small grass huts with no roofs; these structures were more of a shelter than a home.

As the western part of the United States saw more and more white settlers, tensions arose between the immigrants and the indigenous Shoshone. The second half of the 19th century brought with it several wars and skirmishes. These raids culminated in the Bear River Massacre of 1863, when between 350 and 500 northwestern Shoshone, including women, children, and babies, were killed by the U.S. Army.

A year after this, the Shoshone joined forces with the Bannock to fight against the U.S. Army in the Snake War, which lasted for four years. But at the Battle of the Rosebud the Shoshone would take sides with the U.S. troops against their common enemies, the Cheyenne and Lakota.

This form of communication relies on hand gestures and shapes, facial expressions, and bodily movements rather than sounds. We tend to associate sign language with people with hearing disabilities, but in fact it was an essential form of communication within the Native American community, used as a “lingua franca” or universal language.

By the late 19th century, researchers estimated that there were at least 70 different languages belonging to the various tribes across North America. These languages also encompassed different dialects within individual language groups, making the possibility of intertribal communication even more tricky. However, a language of signs rather than sounds developed naturally and provided a means of communication between all these disparate tribes and societies.

Indian Sign Language was largely used by the Plains Indians, those nomadic tribes that ranged the land from the Mississippi to the Rocky Mountains and who spoke many different languages. Tribes here included the Sioux, Kiowa, Blackfoot, and Cheyenne. Because signs can represent ideas that are universal, they can transcend the barriers of the spoken tongue.

Unlike the sign language used by the hearing disabled, which can incorporate facial expressions, the face of the Native American using sign language remains impassive. It is a language of composure and dignity. Chiefs using sign language would command the attention of their listeners, since they would have to be watched closely and the “listeners” would have to be aware of subtleties in order to give a full reply. During warfare, sign language enabled Indians to communicate with one another silently, and in such a manner that few white men would have understood. In hunting, too, sign language would have allowed for communication at a distance which vocal sounds could not have covered.

The first white men to try sign language were the trappers, the fur traders who were known as tough mountain men. The missionaries and scouts also used it. Sign language meant that there was a universal way of communicating between tribes, and sign language interpreters were employed by the U.S. Army.

Because many Native American peoples were nomadic or needed to move over vast areas for the hunt, it was important that they were able to communicate with one another over these huge distances. They exhibited ingenuity in their methods of doing so.

The smoke signal is one of the best-known methods of signaling. In order to do this, a small, hot fire would be constructed and, once it was burning well, damp grasses and fresh greenery were added to make the fire smoke. A blanket—often dampened—was held over the fire and then taken away in order to release the smoke, which could be seen from some way away.

Fire was also used to signal at night using fire arrows, often to indicate someone’s location.

Otherwise, the way a Native American rode his pony could also spell out a signal to someone watching from a distance and with whom a code had been agreed. Repeated circling, for example, would alert a watcher and pass on a message; if the pony and rider disappeared, this could mean that danger was ahead.

Colorful blankets were used as a kind of semaphore, and the light glancing from a mirror was also used in a similar way to Morse code. Otherwise, pictures and symbols might be drawn on a rock; a drawing of arrows might be a warning of an enemy attack, for example. Sign language—necessary to find common ground where there were so many different tongues and dialects—is covered under a separate entry in this book.

The term “Sioux” is used to refer to seven different tribal families which, in turn, are organized into three further units: the Teton (also called Lakota/Dakota), the Yankton, and the Santee.

The peoples that collectively came to be known as the Sioux were settled on the Upper Mississippi River in Minnesota by the 1500s. Back then, they didn’t call themselves the Sioux but went under the name of the “Seven Council Fires.” Each of the seven fires, of course, symbolized a Nation, and those seven Nations were the Mdewakanaton, the Wahpeton, the Wahpekute, the Sisseton, the Yankton, the Yanktonai, and the Teton/Lakota. These tribes would all meet together once a year to discuss any tribal matters and also to renew friendships with one another. They would also choose their four leaders at this time. The last time that the Seven Fires met was in 1850, and the first time that they were recorded as the “Sioux” was when the French interpreter Jean Nicolet noted the word in 1640.

See Treaty of Fort Laramie

This is a Hopi word referring to a small hole or hollow in the floor of the kiva (ceremonial chamber) of the ancient Zuni people. The sipapu is a physical representation of the entrance through which the ancestors emerged into the material world. In his renowned book, The Way of the Shaman, Michael Harner posits that the sipapu could have been a portal for two-way traffic:

“Although I have no hard evidence, I would not be surprised if the members of the medicine societies at Zuni used the holes to enter the Lowerworld when in trance.”

One of the original seven tribes of the Lakota/Dakota whose name, in their own language, means “lake village.” They lived in the neighborhood of Mille Lacs—in French, “a thousand lakes,” in the interior northeast of the Mississippi River close to the Wahpeton and Mdewakanaton peoples.

“I do not wish to be shut up in a corral. All agency Indians I have seen are worthless. They are neither red warriors nor white farmers. They are neither wolf nor dog.”

1831(?)–1890

Arguably one of the greatest and best known of the Native American chiefs, and the last to surrender to the white man, the infant who would go on to become Sitting Bull was born on the Grand River in South Dakota sometime between 1830 and 1834, into the Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux tribe. His first name was Slon-He, meaning “slow,” but as a young boy he was nicknamed “Jumping Badger.” In common with other young Native Americans, he learned the arts of war from the moment he could walk, and went on his first buffalo hunt when he was ten. At 14 he first “counted coup” (See Counting Coup) when he was part of a war party against a band of Crow. At this point he was called “Four Horns.” In 1857, when he became a medicine man, he was named Sitting Bull, or, in the Lakota language, Thathanka Iyotake. The name describes an intractable stubbornness and determination, qualities which he would prove to possess in abundance. Being a Holy Man or medicine man did not prevent a Native from being a warrior, and Sitting Bull was no exception.

His first encounter with the European enemy came in 1863; two years later he led a siege against the recently established Fort Rice in North Dakota. The Black Hills of Dakota were considered sacred to the Sioux. In 1868 Sitting Bull was, allegedly, recognized as leader of all the Lakota people—although this claim was disputed because the Lakota population was scattered over a large area. Whatever the technicalities, Sitting Bull was respected not only for his fearlessness and strategic thinking, but for his perspicacity and foresight.

Numerous incidents that describe Sitting Bull’s legendary courage and calmness have been recorded. One such event describes how, in 1872 during a battle with U.S. soldiers who were protecting railroad workers, the chief led four other warriors out to sit between the railroad tracks, calmly sharing a pipe while the U.S. Army bullets whizzed around them. After they had finished, Sitting Bull calmly and carefully cleaned out his pipe, and he and his men got up and casually walked away, unscathed.

In the meantime, the Treaty of Fort Laramie, in 1868, had effectively protected the sacred Black Hills of Dakota from incursion by white men. However, when gold was discovered in the Hills all hell broke loose as prospectors started to trespass into the area. In 1874 an expedition led by General George Armstrong Custer, along with a posse of journalists and eager prospectors, had arrived in the Black Hills to confirm the discovery of gold in the region. The U.S. Government wanted to buy the land from the Sioux, or at least to lease it, but the Native Americans refused. The Treaty of Fort Laramie was effectively abandoned, and the Lakota were ordered to relocate to allotted reservations by the end of January 1876, or else by default designate themselves as “hostiles” and face the wrath of the U.S. Army. Sitting Bull, true to his name, stayed put with his people.

In March 1876, as three columns of Federal troops under General George Crook started to move into the area, Sitting Bull called together the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Lakota Sioux to his encampment at Rosebud Creek, Montana, where he led a powerful Sun Dance ritual. Slashing his arms 100 times as an offering to Wakan Tanka, Sitting Bull gazed into the sun for several hours; at this point he had a vision that the white soldiers were falling from the sky. This he took as a sign that the Natives would win this battle.

Encouraged and inspired by this supernatural vision, Crazy Horse, another great leader of the Oglala Lakota, set out with 500 warriors to confront the white soldiers. Taking Crook’s army by surprise, Crazy Horse and his band forced them to retreat in a fight called the Battle of the Rosebud. The Lakota then moved their camp to the Little Bighorn River valley. Here they were joined by the massed ranks of over 3,000 Native Americans, who had quit the reservations to follow Sitting Bull. When the Indians were attacked by the impetuous General Custer, the white leader found to his cost that he was severely outnumbered, and his army was routed in one of the most infamous defeats in all of American history at the Battle of Little Big Horn.

This humiliating military defeat stirred up a deal of public outrage, and over the course of the next year the Lakota were relentlessly pursued by literally thousands of soldiers, mainly cavalrymen. Although many other chiefs were forced to surrender, Sitting Bull, true to his name, remained intractable, refusing to surrender. Sitting Bull led his people north of the border into Canada, to Saskatchewan, where they would be out of the reach of the U.S. Army. The difficult achievement of getting to Canada unscathed further enhanced Sitting Bull’s reputation as a great medicine man, attuned to mystical forces. Occasionally Sitting Bull was offered a “pardon” and the chance to return to the U.S. Every time, he refused.

Four years after they first reached Canada, however, Sitting Bull realized that his people simply could not survive there. The buffalo, once their key means of survival, had been hunted almost to extinction. The winters were bitter, and the Indians were starving as well as freezing to death. In 1881 Sitting Bull finally made the journey south to surrender. He asked his young son to hand his rifle to the officer at Fort Buford, hoping to encourage the boy to become a friend of the white men. Sitting Bull tried to negotiate the terms of his surrender, asking for the freedom to be able to enter and exit Canada whenever he wished, and for a reservation to be established near the Black Hills, at the Missouri River where he had been born. However, Sitting Bull and his band were sent instead to the Standing Rock Reservation in northern South Dakota, far from the Black Hills to the west. The reception Sitting Bull received upon first arriving at Standing Rock made the U.S. Government aware of his popularity; fearing a new uprising, they sent him to Fort Randall, on the south side of the Missouri River. Sitting Bull was held at Fort Randall for two years as a prisoner of war. In 1883 he was released and went to rejoin his tribe at Standing Rock, where he tilled the land and farmed; the land agent James McLaughlin was eager to make sure that the great chief was offered no special privileges.

In 1885 Sitting Bull’s life took a strange new turn when he was invited to join Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show. All he had to do was ride around the arena once in order to receive the sum of $50 a week. But Sitting Bull found the company of the white men very difficult to countenance, and left after only 16 weeks.

Back at Standing Rock, Sitting Bull lived in a cabin by the Missouri River, still refusing to accept Christian values, and living with his two wives. He did concede that his children would be better off in the future if they could read and write, though, and accordingly they were sent to the reservation’s Christian school.

Sitting Bull, around about the time he returned to Standing Rock, had another revelation. Given a message from a bird—allegedly, a meadow lark—he suddenly “knew” that he would be killed by one of his own people.

In the meantime, a new craze was spreading among the Sioux tribe. This was the Ghost Dance, or Spirit Dance. In essence, the Native Americans believed that performing this ritual—a circle dance held over a fourday period—would result in the thousands of slain Indians being restored to life, and the peaceful retreat of the white men. In addition, the Natives were encouraged by Ghost Dance leaders to return to their traditional values, eschewing the weapons, goods, and values of the white settlers. Sitting Bull had initially set himself apart from the craze, but observed with interest, knowing that it was giving his people some hope during desperate times. In 1890 he was approached directly by a Miniconjou warrior, Kicking Bear, and informed about the rapid growth of the movement.

The U.S. Government authorities were already becoming nervous about the Ghost Dance Movement. Sitting Bull was hugely revered, a Holy Man and a great spiritual leader. The last thing they wanted was for him to endorse the craze in any way. They considered it so alarming that troops had already been called onto the reservations at Rosebud and Pine Lodge to control the crowds. Accordingly, troops were sent to arrest Sitting Bull. In December, 1890 they arrived at his cabin early in the morning, and surprised the chief as he was asleep. Initially, Sitting Bull came peacefully, but when a couple of the arresting officers started rifling through his cabin and throwing things around, he grew agitated, and the men had to drag him outside where his followers were gathering, having heard what was happening. There were gunshots and confusion. A Lakota policeman, Red Tomahawk, shot Sitting Bull through the head. Sitting Bull’s prophecy—that he would be killed by one of his own people—had come to pass.

Luckily, we know many of the details of Sitting Bull’s life because he depicted them in drawings not long before he died. These images are now kept at the Smithsonian Institution.

Sitting Bull’s body was buried at Fort Yates in North Dakota. However, in 1953 his remains were disinterred and moved to Mobridge in South Dakota. There was an argument between the two states as to which one should claim the right to be the site of his final resting place. Sitting Bull remains in South Dakota, a huge granite shaft marking the place where he is buried.

1838–1897

A member of the Squaxon tribe of the Pacific Northwest, the Native American Squ-sacht-un, otherwise known as John Slocum, had an important role to play in the introduction of a new religion to the Native Americans.

In common with multitudes of Native Americans, John Slocum had been introduced to Christianity by the missionaries, and had embraced the new faith. In the early 1880s Slocum, who was living with his family on a reservation, fell ill. When he recovered, he described an ecstatic vision that he had had. While ill, he had entered a trancelike state in which he was taken to Heaven and shown the ways that the salvation of the Indians could be brought about. The drive from this vision was such that in 1886 he built a church in which he could preach about his vision and its accompanying chance of salvation.

However, Slocum became ill again in 1887 and his wife, Mary Slocum, unaccountably began to shake and shudder while physically close to her husband. Once again John recovered and decided to incorporate shaking and twitching into his church’s religious practice, as a way of “shaking off” sin. The faith, which was a syncretism between Native American spiritual beliefs and all the trappings of Christianity, including a belief in Heaven and Hell, thus became known as the Indian Shaker Religion.

Despite his absorption of Christianity, Slocum was still persecuted by the U.S. Government, and was imprisoned frequently for resisting the move toward assimilation.

The Indian Shaker Religion is still practiced today.

The coming of the white man had many devastating effects on the indigenous peoples of America. European diseases caused a colossal number of deaths and illness, particularly so because many of the infections had never been known in America and so the Native peoples had absolutely no immunity to them. The diseases that caused the most harm included smallpox, measles, bubonic plague, syphilis, and mumps. Although the diseases generally spread accidentally, it is also likely that sometimes they were introduced deliberately with the aim of reducing the Native American population, although this is very difficult to substantiate with 100 percent certainty.

It is also difficult to assess precisely how many people were lost because of these diseases. We know that the Seneca, for example, were so reduced in numbers after they contracted scarlet fever and bubonic plague that their four settlements were reduced to two. Also, Seneca pottery dated after the infection is much rougher and less skilled than beforehand; the inference here is that this, and other, cultural knowledge may have been lost. We’ll never know for sure.

Mythology surrounds the bringing of tobacco, and the pipe, and the accompanying ceremony and ritual pertaining to their use.

In Sioux stories, the White Buffalo Calf Woman appears to mankind, bringing the gift of the pipe and instructions about how to use it. In Huron myth, another goddess figure appears, an envoy of the Great Spirit, come to save mankind. As she travels all over the world, anywhere that she touches the soil with her right hand, potatoes grow. Her left hand touching the earth draws forth corn. Once the whole planet has been made fertile, the woman sits down to rest. When she stands up again, goes the story, tobacco is growing where she rested.

Although tobacco is now a hugely important commercial crop, and the smoking of it is cause for concern because of the illnesses it brings in its wake, the ritual use of tobacco is a very different matter. The tobacco itself—considered a sacred herb—was never meant to be abused in the way it now is. For Native Americans, smoking tobacco was a ritual act, intended to show respect to the Great Spirit, to protect, and also to heal. Prior to the coming of the Europeans to America, tobacco was used as medicine. After their arrival and their discovery of the herb, the management of the tobacco crop became big business, the revenue generated from it used to support the establishment of the colonies. It was so important that the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. has leaves of the tobacco plant sculpted into its columns. The same tobacco-leaf emblem was also used on coins during the American Revolution.

For many, it is difficult to think of commercially available cigarettes, product of myriad tobacco companies, as a sacred herb. In fact, this sort of tobacco is not considered to be sacred at all, and Native Americans were quick to differentiate between commercially cropped tobacco and the “real thing” as used for spirit work.

As with any ritual, understanding comes from actually experiencing it, and so describing the smoking ceremony doesn’t really do it justice. The combination of the pipe (the mechanism by which the smoke is made), the tobacco (the sacred herb which produces the smoke), the smoke itself (connecting the physical to the spiritual world), and the spark which causes the tobacco to burn, creates a microcosm. When that pipe is shared around a circle, the celebrants are unified. Further, the pipe is offered to the directions and the elements, north, south, east, west, above and below; George Catlin describes a contemporaneous account of this in his book, North American Indians, first published in 1898:

“ … one of the men in front deliberately lit a handsome pipe, and brought it to Ha-wan-je-tah to smoke. He took it, and after presenting the stem to the North—to the South—to the East, and the West—and then to the Sun that was over his head, and pronounced the words ‘how-how-how!’ drew a whiff or two of smoke through it, and holding to bowl of it in one hand, and its stem in the other, he then held it to each of our mouths, as we successively smoked it; after which it was passed around the whole group …”

And further, Catlin explains:

“This smoking was conducted with the strictest adherence to exact and established form, and the feast the whole way, to the most positive silence. After the pipe is charged, and is being lit, until the time that the chief has drawn the smoke through it, it is considered an evil omen for anyone to speak; and if anyone break silence in that time, even in a whisper, the pipe is instantly dropped by the chief, and their superstition is such … another one is called for.”

Ed McGaa, also known as Eagle Man, the Sioux author of Mother Earth Spirituality: Native American Paths to Healing Ourselves and Our World, first published in 1995, elucidates the connections with those six directions. The west is a reminder of the ever-present spirit world, and the essential rains. North stands for honesty and endurance. East is a reminder of the rising sun, which brings with it knowledge and the absolute essence of spirituality. The south direction brings abundance, healing, and growth.

Touching the pipe to the ground connects with the spirit of the earth, the Mother. The sky is acknowledged as essential to the earth. Finally, the pipe is offered to Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit, and in the words of Eagle Man, the following prayer is spoken:

“Oh Great Spirit, I thank you for the six powers of the Universe.”

Use of a smudge stick is called smudging. The stick itself is a bundle of dried herbs, often including white sage, tied into a long bundle. Other herbs that are often incorporated into the stick are lavender, mugwort, cedar, cilantro, yarrow, rosemary, juniper, and artemesia. Smudging is carried out as a form of purification and for driving out bad spirits, and is by no means restricted to Native American peoples. The use of incenses and smoke is a core spiritual practice all around the world, and smudging in particular has been adopted by many practitioners of various New Age therapies.

Traditionally, the Ojibwe and Cree smudge sticks incorporated sage, sweet grass, balsam fir, and juniper.

The Snake Dance or Snake Ceremony of the Hopi was a major part of their ceremonial practice. It was, at its essence, a prayer for rain. In the dance, the priests performing the ceremony would dance around the village while carrying live snakes (including venomous rattlesnakes) in their mouths. The finale of the dance saw the release of the snakes back into the wild at the edge of the settlements, sent back to the gods to appeal for rain to come. While other snakes were used as well, the most poisonous and potentially lethal one was the rattlesnake. Whether or not the fangs of this snake were removed prior to the dance is unknown, but it seems unlikely since an antidote would be prepared prior to the ceremony. Another part of the cure for rattlesnake bite was to place the belly of the snake on the wound, although the efficacy of this method has to be doubted.

Theodore Roosevelt, writing in 1916, describes in great detail an account of a Snake Dance ceremony that he witnessed, and even back then it seems to have become a tourist attraction. He says in A Book Lover’s Holiday in the Open:

“I have never seen a wilder or, in its way, more impressive spectacle than that of these chanting, swaying, red-skinned medicine men, their lithe bodies naked, unconcernedly handling the death that glides and strikes, while they held their mystic worship in the gray twilight of the kiva …”

The Inuit invented something very like modern-day snow goggles almost 2,000 years ago. Although they didn’t have a transparent shield, the “goggles,” carved from bone or tusks, had narrow slits that protected the eyes from the glare of the snow and the sun.

A hunting method used during the winter months, a snowpit, as the name suggests, was a hole made in the snow which was large enough for the hunter to hide in so that he could get closer to his prey.

1871–1913

The first Native American Major League baseball player who did not feel the need to conceal his background, Louis Sockalexis was a Penosbcot. In 1897 he was selected to play for the Cleveland Spiders. An immensely talented athlete, he could apparently throw a baseball the 600 feet across the Penobscot River. However, Louis was taunted because of his Indian blood, shouted at, heckled, and even spat at. Under this pressure, the star player developed a drinking problem and his game suffered considerably after he broke his ankle at a party. In 1915 the Spiders changed their name to the Cleveland Indians—it is believed that this might have been, in part, in honor of Louis Sockalexis.

A piece of magical equipment used by the shaman and medicine man of some tribes, including the Haida. The soul catcher was a tube carved of bone, which was used to capture the wandering spirit of the sick and return them to their bodies. The end of the tube was placed in the mouth of a sick patient; when his or her own spirit re-entered the body, it was believed that the evil entity that had caused the illness in the first place would be expelled.

The Spokane—or Spokan—people lived in the eastern part of Washington along the banks of the Spokane River. The name means “People of the Sun” and they were a part of the Salishan group. Because of the proximity of the river, fishing was a fundamentally important way of life for the Spokane, and salmon formed a large part of their diet. The fish was supplemented with wild fruits and plants including the camas.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition encountered the tribe in 1805, after which the fur trade in the Spokane territories was developed by the colonists—to the extent that trader John Astor became the wealthiest man in America. The tribe were well-disposed toward the white settlers although, like other tribes, they had no natural immunity to the diseases carried by the white men and consequently suffered devastating effects from smallpox in the 1840s and 1850s. Eventually, the relentless incursions by the white men, combined with their reneging on treaties, caused this peaceable people to protest. The Spokane, the Paiute, and the Palouse were among some of the Native peoples who allied together and rose up in 1858; this rebellion became known as the Spokane War. After the war, the Spokane were relocated to different reservations in the Washington area. Some aligned with the Flathead, also of the Salishan family.

1826–1890

Chief of the Miniconjou band of the Lakota Sioux, Spotted Elk was known in his own language as Hehaka Gleska and also as “Big Foot.” This latter was intended as a derogatory name, given to him by an American soldier. Spotted Elk became chief in 1875 after his father, One Horn, died at the ripe old age of 85.

Although he was a skilled warrior, Spotted Elk was renowned for his reputation as a peacemaker, and was called upon regularly to settle disagreements and quarrels within the Teton bands of the Miniconjou. Cousin to Crazy Horse, Spotted Elk, his half-brother Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and Touch the Clouds united their tribes together in the 1870s against the U.S. Army. Defeated during the Sioux War of 1876–1877, Spotted Elk’s men surrendered. Part of the settlement after the war saw the Miniconjou relocate to the Indian Reservation in South Dakota, where Spotted Elk did all he could to encourage his people to follow the instructions of the white men, and become farmers. His peacemaking skills would have been key during this time.

Conditions on the reservations were not as promised, however; living conditions were poor and the Lakota struggled to survive, hindered not only by the conditions but by corrupt Indian agents who did not supply the promised rations.

Then the Ghost Dance Movement reared its head among a people that were starving, disillusioned, and desperate for change. Spotted Elk and his people embraced the movement wholeheartedly as the solution to their problems. Other Sioux bands, too, caught onto the movement, which spread like wildfire.

After Sitting Bull was shot in 1890 by the Government, who were alarmed at the spread of the Ghost Dance, his followers descended on Spotted Elk’s camp for protection. Spotted Elk in turn traveled to the Pine Ridge Reservation to visit Red Cloud, hoping to be able to restore peace. Unfortunately, however, Spotted Elk caught pneumonia on the journey and the Cavalry caught up with them, whereupon Spotted Elk, delirious with fever, surrendered willingly. He and his men were taken by the Army to Wounded Knee Creek to join the camp that was already set up there.

Spotted Elk was among those who were killed in the Wounded Knee Massacre that occurred on the morning of December 29.

“This war did not spring up on our land, this war was brought upon us by the children of the Great Father who came to take our land without a price, and who, in our land, do a great many evil things … This war has come from robbery—from the stealing of our land.”

1823–1881

Born in South Dakota and named Sinte Gleska (“Jumping Buffalo”), this Brule Lakota was born into a time of great change for his people and for the Native American population. The Sioux had moved from their hereditary areas in South Dakota and Minnesota toward the area west of the Missouri River, had split into different sub-divisions (including the Oglala and the Brule), and were using horses to hunt the buffalo.

Reared by his grandparents after the death of his parents, as a young man he was given the gift of a raccoon tail from a white trapper—hence the name he came to be known by, Spotted Tail. He took to wearing this tail as part of his warbonnet. Spotted Tail was acknowledged early on as a war chief after a skirmish with the Ute, when his clever tactical fighting resulted in a Sioux victory even though they were outnumbered.

A born diplomat who took every opportunity he could to observe people and learn from them, Spotted Tail, despite his skill as a warrior, believed that fighting was never the way to any long-term solutions. Accordingly, he was among those who agreed to the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, which was supposed to protect the Sioux territories from encroachment by white settlers. But in 1874, after General Custer led a gold-hunting expedition into that same sacred land, which led to a mass encroachment by eager prospectors, it seemed that the already uneasy peace between the Sioux and the white man would be shattered. A year later, a delegation of chiefs including Spotted Tail and Red Cloud traveled to Washington, D.C. to attempt to persuade President Ulysses S. Grant and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Ely S. Parker, to honor the agreement they had made in the Treaty of Fort Laramie. However, the chiefs were told that the Government had a solution to the problem: rather than protecting the land, as they had promised, the Government suggested they simply pay the Native Americans for their hereditary and sacred lands and move the tribes to reservations within the Indian Territory (in what is now Oklahoma).

The chiefs refused this arrangement, expressing their desire to follow the agreed terms of the Treaty instead. Spotted Tail was quoted as saying:

“When I was here before, the President gave me my country, and I put my stake down in a good place, and there I want to stay … I respect the treaty but the white men who come in our country do not. You speak of another country, but it is not my country; it does not concern me, and I want nothing to do with it.”

The Great Sioux War of 1876–1877 followed; Spotted Tail managed to keep his people under control and, as a result of his diplomatic approach, became involved in the negotiations that eventually did lead to the sale of the Black Hills in South Dakota. Spotted Tail subsequently became Chief of the Brule and Oglala Sioux. Despite this, Spotted Tail did not involve himself in the leadership of Red Cloud’s Oglala people.

Spotted Tail, who was related to Crazy Horse, was instrumental in getting that firebrand warrior to surrender; unfortunately, this led to Crazy Horse’s death in 1877 when an attempt was made to imprison him. Spotted Tail was blamed for this, and in 1881 he was shot in the chest by Crow Dog, a supporter of Crazy Horse. Spotted Tail died instantly. He is buried in Rosebud Cemetery in Montana.

See Tisquantum

If a white man married a Native American woman, this was the name that he was given. Although the term was a derogatory one, in fact many wealthy and successful men were “Squaw Men.” For example, the eminent geographer, geologist, and ethnologist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft married a Native American woman—when she died, he married another.

A part of the Salishan language family, the Squaxon were a part of the coastal Salishan people and lived in the bays of Puget Sound, in what is now the northwestern part of Washington state. Their close proximity to the ocean led to them calling themselves “the People of the Water.”

Naturally, fishing was an important way of life for the Squaxon. Their diet, primarily seafood, was augmented with foraged plants and some small game. With the coming of the Europeans, their traditional way of life was threatened. The Treaty of Medicine Creek in 1854 saw large quantities of the Squaxon ancestral lands ceded away. They were left with Squaxon Island, which was only some four and a half miles long and just half a mile wide. Some of the Squaxon staged a rebellion with the Nisqually people in the mid-1850s, but this failed.

“We lived on our land as long as we can remember. The land was owned by our tribe as far back as memory of men goes.”

c.1834–1908

Born into the Ponca tribe, Standing Bear is most famed because of his successful argument in court that a Native American was actually a person within the eyes of the law. This happened in 1879, and although it might sound strange now, at the time this ruling was nothing short of revolutionary, and the court judgement made it a landmark case.

At the time he was born, Standing Bear’s people followed the bison in winter, and in summer settled down in their traditional homes, planting and harvesting crops such as corn, squash, and beans, and various fruits. Agriculture was slowly superseding hunting as a means of subsistence, although fishing was also important. Standing Bear would have learned to farm, hunt, and fish. Aside from raids by other Indians, primarily the Brule, life would have been peaceable and stable.

Then, in 1854, a Government act encouraged a large influx of European settlers, and the tribes in Nebraska—including the Ponca—were forced to cede their land to the U.S. Government to accommodate the incomers. In three short years, where the summer maize fields had once stood, a town, Niobrara, was now being built by the white settlers, and the Ponca were forced onto land that was poor for farming. Although the Government had promised to supply the tribe with schools, mills, and protection, this promise was broken and, as a result, the Ponca were starving, impoverished, and still suffering on account of raids by neighboring tribes.