Popular Media of the

Vietnamese Diaspora

Stuart Cunningham and Tina Nguyen

The Vietnamese diaspora is arguably unique in this study, because of its historical roots in refugee-exile circumstances. Being originally refugees and only lately immigrants makes the Vietnamese peoples in the Western world very aware of the pull between maintaining their original cultures and adapting to their new host cultures. They are thus most similar, of any Asian-Australian group, to Naficy’s (1993) Iranian exilic community. They contrast in the recency of their diasporic history with, for example, the Chinese community in Melbourne. They also contrast with the Chinese and Indian communities in their part-reliance on non-Vietnamese audiovisual media, because the Vietnamese industry is very small and there is a negligible export dynamic, but most importantly because most overseas Vietnamese reject the output of the “homeland” as fatally compromised by being produced under a communist regime.

The Vietnamese is by far the largest refugee community in Australia. For most, “home” is a denied category while “the regime” continues in power, so media networks—especially music videos—operate to connect the dispersed exilic Vietnamese communities. Small business entrepreneurs produce low-budget music video mostly out of southern California, which are taken up within the fan circuits of America, Australia, Canada, France and elsewhere. The internal cultural conflicts within the communities centre on the felt need to maintain pre-revolutionary Vietnamese heritage and traditions; find a negotiated place within a more mainstreamed culture; or engage in the formation of distinct hybrid identities around the appropriation of dominant Western popular cultural forms. These three cultural positions or stances are dynamic and mutable, but the main debates are constructed around them, and we will use them as a way of organising our analysis of the cultural and media environment.

This chapter will treat the media businesses that specifically service the Vietnamese diaspora; the media consumed; and the active appropriations made of media. Between 1995 and 1999, business interviews were conducted at the headquarters of the main Vietnamese music video production companies in Westminster, Orange County and some of their distribution representatives in Bankstown, New South Wales; several video store proprietors in Brisbane; and with newspaper editors in Sydney. Interviews with several performers and other artists who make a living from live and recorded performance and music video activity (discussed in “Vietnamese Diasporic Video”, below) were also conducted in person in Southern California, Sydney and Brisbane and by email.

For audience response, the “affinity group” methods used were appropriate to tracking forms of fan and less intense consumption of the central media. This involved the research team establishing initial contacts through professional and community associations, workplaces and personal relationships, and then working out from these by “referral-on” to establish an adequate base of diverse consumption patterns and relations to media. Semi-structured interviews with community leaders and in households; focus groups assembled through community associations and through a special school for recent migrants; and participant observation of festivals, concerts, celebrations and karaoke sessions, together with television and video viewing in homes in Brisbane, Sydney and Westminster, were all used in the course of the research.

The most detailed audience response research, in Brisbane, was conducted with two families who were first-wave refugees and whose members held some responsible positions in the community; a brother and sister (and their regular clientele in the coffee shop) who are extremely well-informed fans and who run a grocery store and an adjacent coffee shop where karaoke and music video are played; a large group of recently arrived teenagers on the family reunion program assembled through their school; and a working class group of youth, many of whom were unemployed and who had had limited education. We will use the term “respondents” or “informants” in most cases when referring to activities undertaken or insights offered. Sometimes this will be supplemented by a description of the social location of the respondent(s). In a few cases, we will use the actual names of people who have engaged very strongly with the project, providing richly textured responses and insights that they were happy to share publicly.

Basic Demography

The Vietnamese have had a long history of migration within their immediate region, but a very limited history of migration outside of Vietnam. By 1975 only about 100 000 Vietnamese were living outside Vietnam. Australia’s earliest record of Vietnamese migration goes back to August 1920, when a group of 38 Vietnamese aboard a ship transporting labourers blew off course and ended up in Townsville. Australia next encountered Vietnamese in the country as part of the Colombo Plan from the late 1950s. By 1975, 335 Colombo Plan students were attending Australian universities along with some 130 private school students.

However, from 1965–75, during the height of the Vietnam (or “American”) War, over half of Vietnam’s population was displaced internally, and now the Vietnamese diaspora numbers something over 2 million Vietnam-born throughout the world. (The current population in Vietnam is 76 million, whereas in 1975 it was estimated that the population of Vietnam was 60 million.) To this, of course, should be added the second generation—those born to Vietnamese parents in the host countries—whose numbers are notoriously not reliable because census data collection in several countries follows widely variant protocols, but are estimated at at least half a million.

About half of the total diaspora is domiciled in the United States, with significant population centres in Orange County, San Jose, Texas, Minneapolis, Washington and Houston. Other major host countries include France, Canada, Germany and The Netherlands, as well as Australia. The 1996 Census figures show a little over 151 000 Vietnam-born people in Australia, to which numbers should be added a substantial second generation. Given the fraught history of the treatment of refugees in the immediate East Asian and Southeast Asian region, it is not surprising that there are very few Vietnamese resettled in the country’s immediate region. Overall, there are about 70 population centres across the world with some Vietnamese presence outside the “homeland”.

It is a small diaspora but one which has had a very high profile internationally because of the implication of major Western countries in the conditions which led to the creation of the group: the US and French involvements in Vietnam, together with the crucial nature of the Vietnam War for the course of international relations and ideological alignments in the 1960s and the 1970s. Also, the nature of escape—particularly by boat—from the homeland in the late 1970s and early 1980s constituted one of that period’s ongoing international media events. The acceptance of Vietnamese refugees, including the so-called “boat people”, during this period was the first major test of Australia’s liberalised, post-”white Australia”, immigration policies, and arguably its major humanitarian project in response to war and refugee displacement since World War II (Thomas, 1997: 274–75).

It is also a very recent diaspora, with virtually the entire overseas refugee and immigrant population resettlement occurring since 1975, and the median period of residence in Australia in 1995 being nine years (Viviani, 1996: 83). There has been an exceptionally high level of attention paid in the media to the Vietnamese population in Australia, despite the very small size of this population:

The strong profile of the Vietnamese population in the broader Australian community is partly due to their relatively spatial concentration in our largest cities, high unemployment rates and comparatively low levels of English proficiency. There is, however, a danger in stereotyping the attributes of the Vietnam-born, as a superficial examination of their dominant socio-economic features can mask the more complex nature of spatial mobility and status differentiation . . . it has become clear that, among the Vietnam-born, there is a persistent pattern of accelerating socio-economic diversity, along with important class, status and ethnic differences. (Thomas, 1997: 275)

Further indicators of the specialness of the group are brought forward by Viviani (1996). The Vietnamese are over-represented in university attendance, with twice as many of those born in Vietnam at a university than the Australian-born population, but they are also over-represented in gaols, with longer sentences for more serious crimes. The rate of consumption of and reliance on video and television is to some extent related to rates of under- and unemployment (Viviani, 1996: 111).

It is widely known as an exilic diaspora, although the proportion of the overseas Vietnamese who began their resettlement as refugees has declined all through the 1990s as the Doi Moi (Renovation) policies of the Vietnam government have permitted structured legal emigration since 1989. In the mid-1990s in Australia, only around 30 per cent of the population were originally refugees (Viviani, 1996: 83). The Vietnamese have arrived in Australia (from 1975 to the present) in four main waves. The first two, in the mid- and late 1970s and the early 1980s, were refugee intakes, including the so-called boat people. The latter of these refugee movements was predominantly of the ethnic Chinese, whose small-business interests were specifically targeted by the communists for expropriation and nationalisation. The last two major waves, in the mid-1980s and early 1990s, were mostly immigrant intakes, predominantly under Australian government immigration policies of family reunion. When the Australia-born group is added (in 1995, there were about 180 000 Vietnam-born or second generation), it becomes clear that the proportion of the population who were refugees/exiles is rapidly declining. Also, since the 1986 Census, there has been a dramatic rise in older age groups due to family reunion, and thus a growing difference between recency of arrival (older age groups and relative lack of English proficiency) and generational difference (the young are predominantly Australian-born and have experienced greatest acculturation to the host country).

Over 30 per cent of the Vietnam-born population claim Chinese ancestry (the ethnic Chinese) and, while it is not readable from Census data, there are sizeable proportions of the population who have undergone double and triple migratory experiences, having migrated internally from the north to the south or central regions as a result of Ho Chi Minh’s Communist assumption of power in 1954 and then moved again out of the country during the 1970s. Thus there are significant differences along axes of generation, ethnicity, region of the home country, education and class, and recency of arrival and conditions under which arrival took place amongst this small population.

“Structured in Dominance”: The Vietnamese Media Diet

The Vietnamese media diet is “structured in dominance”: while mainstream media offer little of relevance and can be perceived as, in one respondent’s calmly diplomatic word, “unfriendly” in the way they portray the community, there are therefore of necessity a range of alternative media that in varying degrees service community information and entertainment needs and desires. So, with an emphasis on agency in media use, the study of the interpretative community at work might start with those forms which Vietnamese audiences have least access to and control over—dominant broadcast and print media—move to specialist broadcasters and to language-specific print forms such as ethnic newspapers, but stress those electronic media which embrace both information and entertainment and which are engaged with most strongly as indicators of popular cultural capital: Hong Kong video product and Vietnamese live variety shows and music video—the latter a form unique to the diaspora as audiovisual media made by and for the diaspora.

The Televisual Mainstream

Most of those respondents who worked full-time asserted that they were too busy to watch broadcast television regularly; and of those who did watch (mostly under- or unemployed and school-aged young people), it was game shows, soaps and daytime talk shows that were most regularly mentioned as broadcast television fare. Substantial survey-style research has been done on ethnic minority preferences and viewing patterns which report largely negative outcomes for broadcasters’ service to these communities. In spite of the development of various “Advisory Notes”, including one on Cultural Diversity, by the Federation of Australian Commercial Televisions Stations (FACTS) since 1994, there is strong, ongoing evidence for television and commercial radio to be perceived as a distinctly hostile, and at best benignly neglectful, environment for Asian-Australians.

While studies of the mainstream press indicate a broader range of representation, and a greater possibility of stories with positive representation (Pittam, 1993; Pittam and McKay, 1991), these are based on content analysis and cover both soft and hard news genres, with “human interest” stories demonstrating the most positive representations. Studies exclusively of hard news genres are uniformly critical of mainstream coverage of Vietnamese-Australians (Loo, 1994; Thomas, 1996). The work of Hartley and McKee on the “Indigenous Public Sphere”—which constructs as strongly positive an account of Aboriginal agency in the Australian mediascape as possible—opens up importantly innovative avenues in a depressingly predictable field, but even in this work there is a recognition that soft news has been more open to real cultural diversity than hard news genres (Hartley, 1999a; Hartley and McKee, 2000). The field of mainstream media remains virtually a no-go area for Asian-Australians in terms of directly inclusive invitations to identification and engagement.

Perceptions studies (rather than content analysis, either quantitative or qualitative), which seek opinion from representative groupings within the minorities, tend also to produce uniformly critical outcomes. The most extensive of these in Australia is Nextdoor Neighbours, A Report for the Office of Multicultural Affairs on Ethnic Group Discussions of the Australian Media (Coupe et al., 1993). Findings from studies of this type are replicated in similar research elsewhere—for example, in the mid-1990s by the Independent Television Commission (ITC) of the United Kingdom, which found large percentages of ethnic minority groups in Great Britain arguing that mainstream television was biased against ethnic minorities and their religions and in favour of the police force. Seventy-six per cent of Asians, 88 per cent of African-Caribbeans and 52 per cent of the “main” (ethnically undifferentiated) sample agreed that “all too often television portrays negative stereotypes about different ethnic minority groups”. The research concluded that “the overwhelming impression . . . is that viewers from ethnic minorities consider terrestrial television to be ‘white’ television” (Hanley, 1995: 17).

The key mediating institution between the mainstream and specialist mediascapes is SBS. We have considered the broad structural position of the SBS in Chapter 1, and also the significant role its WorldWatch programming plays in Chapter 2. The structural limitations of SBS Radio, and other community-language radio stations in the community broadcasting sector, are that they can provide very small windows for each separate “community” language and are locked into the problems and politics of limited time and resource allocation in a regime of spectrum scarcity. As information sources and language maintainers, SBS and community radio continue to play significant roles for mostly older age groups. However, in 1999, with an estimated four hours per week on community radio, one hour per day on SBS radio, and about 1.5 hours a week on C31, the community television station (if the signal is receivable), community broadcasting barely begins to address the media needs of the Vietnamese community in western Sydney, the largest in the country. A representative of the Vietnamese Women’s Association in Queensland told us that:

About 90 per cent of older Vietnamese listen to Vietnamese radio or hear about news and views in the community in Queensland and the other places in Australia. SBS Radio serves a very important role in the community, people always listen. 4EB [the community radio station in Brisbane] is good but not enough, only one hour at inconvenient time. SBS TV too is very good but also good for many Australians. The people watch SBS movies to read English because it is easier than to hear it.

The adequacy of Vietnamese representation on SBS-TV brings into sharp relief the structural limitations of the service and the politics of particularly refugee diasporas discussed in Chapter 1. In the period 1992–97, only nineteen Vietnamese-language programs were screened, or were purchased to be screened, by SBS. Most were single-episode documentaries, with the rare exception of a feature film such The Scent of Green Papaya. SBS points out that the country has a very underdeveloped production base; there is negligible emphasis on program export (as the Vietnamese language diaspora, compared with the Chinese or the Indian, is opposed to the consumption of homeland material); and there are quality control concerns regarding program suitability for Australian broadcast standards (Edols, 1995; Webb, 1997). Overall, though, the predominating SBS position is that there are structural constraints on programming and purchase policy governed by its charter commitment to multicultural programming for the whole Australian population, not specific sections of it.

The size of the corpus, though tiny, can still attract strong criticism of the screening of many items on the basis that they are barely-disguised “propaganda” for the regime. Documentaries such as Vietnam Church and State (screened in 1993) and Women, the Strength of Vietnam (screened in 1996) attracted criticism for this reason. While a feature such as Cyclo (screened in 1996), by Paris-based expatriate Tran Anh Hung, was “acceptable” to those overseas Vietnamese who may have watched it insofar as it portrays the desperation of the contemporary Vietnamese underclass, an acclaimed international art feature such as Indochine can be suspect. First-wave refugee Trinh’s political criticism of this feature was that it centres on narrative justification for the emergence of Vietcong resistance to the French occupation and, because its narrative ceases at the point at which communist anti-colonialism can be regarded as undeniably progressive nationalism, valorises the origins of the regime from which the refugees ultimately had to flee.

Of course, the charter of SBS-TV, as discussed in Chapter 1, does not address language and cultural maintenance as such, so it is hard to imagine a scenario within the parameters of its single-channel service where the situation described above could change significantly. On the other hand, community newspapers are largely defined by their cultural maintenance role (albeit with significant variations), and are major established media formats designed specifically and exclusively for the community.

Community Newspapers

The first cultural position—that of heritage maintenance—is primarily centred on the ideological monitoring role of maintaining the salience of the anti-communist originary stance foundational to the diaspora. Community-language newspapers are to a large extent controlled by established figures of the first and second wave who were refugees and members of the South Vietnam power elites. As such, they remain powerful voices maintaining the currency of the originating acts and reasons for separation from the homeland. It is not surprising, therefore, that the readership of community language newspapers is generationally skewed towards the older, original refugees and the less English-proficient segments of the population.

The Vietnamese community press, like most print media serving more recent immigrant groups (the most comprehensive analytical study of the ethnic press is Bell et al., 1991), is characterised by an editorial model of strong, often strident partisanship. In effect, many community newspapers contribute to the continued liminalisation of everyday life for their readerships. In this respect, they work on a press model followed normatively by most newspapers up to the end of the nineteenth century, and which continues in many European countries. The development of normative objectivity as a governing principle for professional journalism (“Our reporters do not cover stories from their point of view. They cover them from nobody’s point of view.”—CBS News President from the 1970s, Richard S. Salant, quoted in Cunningham and Miller, 1994: 35) is meant to supplant the partisan model—and it has done so to some extent in ethnic newspaper production in Australia for those communities which are well established over several generations, typically the southern European communities (Kissane, 1988: 32).

As a mark of the partisan model of the press, there is a plethora of ethnic community newspapers in Australia, and the Vietnamese press is no exception. In Australia, from the early days of the Colombo Plan through to the present, there is estimated to have been a total of 92 different types of Vietnamese print publication with some claim to a broad readership (Tran, 1995). While a sizeable proportion of readers expect the newspapers to reinforce the rationale for escape and exile from the homeland, and to provide an information base to facilitate cultural maintenance in Australia (Tran, 1995), there has been differentiation of editorial focus and emphasis during the 1990s in keeping with the shifting demographic profile of the community.

The leading papers with a continuing explicit political refugee editorial line are Viet Luan (The Vietnamese Herald) in Sydney and Nhan Quyen (The Human Rights Daily) in Melbourne. Viet Luan is the main “quality” weekly which has been running continuously since 1983. Established by Nguyen Chanh Si, who was a lawyer in Vietnam before 1975, currently the newspaper is owned jointly by a consortium of local Sydney businesspeople. The typical editorial content balance is one-fifth Vietnamese news, two-fifths Australian news, a community information update and an entertainment, sport and miscellaneous section, while at least half the paper is devoted to advertising. Its influence transcends its 14 000 national circulation. Nhan Quyen was established in 1982 by another former lawyer, Long Quan.

The paper with the widest readership, and one that has developed away from the political refugee editorial line, is Chieu Duong (The Sunrise Daily). Established in 1980, and based in Cabramatta, it went daily in 1986 and remains the only daily Vietnamese newspaper in Australia. Chieu Duong was set up by Nhat Giang, who had established newspapers in San Jose and in France as well. It is run by Nhat Giang’s son, Nhi Giang, in the late 1990s a member of the New South Wales Ethnic Affairs Commission. It has a weekday circulation of 15 000, with the Saturday edition going to 18–19 000. Editorially as well as in format, Chieu Duong is tabloid, minimising political content and emphasising human-interest, society and entertainment news. Other papers include Chuong Saigon (Saigon Bell), which was first published in 1979 and ran to 1993 as mostly a weekly magazine, though for a time it was a biweekly.

The broadest public sites of ideological monitoring are indeed these newspapers. The papers have historically been closely aligned with the Vietnamese Community Organisation, the peak national lobby for the community, which vows constant vigilance against the Vietnam government and its attempts to compromise the integrity of the anti-Communist refugee stance. Attempts by members of the community to have this stance softened—in the interests of either a principled recognition of a changed environment since Doi Moi (Renovation) policies from the late 1980s, or the pragmatics of the advantages of being able to do business or facilitate family reunions—are met with harsh rebuke (see Thomas, 1996: 143). The exception to this is Chieu Duong, which largely avoids these issues of community division, instead facilitating a community identity around shopping, social scandal and entertainment.

A typical example of newspaper heritage maintenance at the time of writing was a campaign against SBS-TV adding Hanoi TV News to its WorldWatch news schedule—programming discussed in Chapter 2. Viet Luan’s edition of 19 February 1999 (pp. 30, 50) editorialises vehemently against such a proposed move, saying that the community has “patiently put up with the screening by SBS of poorly produced, poorly sub-titled Vietnamese programs from Hanoi that often carry naked propaganda messages”. But proposing to add a daily news bulletin is seen as “go[ing] too far”, and the community is asked to mobilise around a petition.

Some of the importance, as well as the ambivalence, accorded the press is expressed in this comment from a young woman who, though her parents had been forced to leave in 1978 because of the communists’ nationalisation of their business, was not wedded to maintaining a reflex anti-communism stance:

Read Asian newspaper just once a week to keep in touch . . . not very true . . . too far away now and they don’t know now . . . yes I agree with them Communists bad before, really nasty . . . but now the way they run the country is far better because they can look after themselves. The Vietnamese papers don’t know any more that’s why I don’t read that part [overseas politics] . . . I just read the community part . . . a lot of news I can’t understand in Australian paper . . . 50–50 I understand that so I read the Asian paper to understand better the politics and economy story . . . mostly read about what happen in Australia . . . like budget . . . I don’t understand in Australian paper.

Mandy Thomas (1996: 145) compares mainstream and community newspaper discourse about the Vietnamese:

The Vietnamese press, while attempting to secure for its readership a sense of control and empowerment, is often overtly political, as well as being a promoter of immutable and uniform images of Vietnamese people in exile. While the mainstream press images the Vietnamese as . . . intrusive and destructive within Australian spaces, the Vietnamese press is often making a plea to its readers to turn their focus of attention beyond Australia, to the past in Vietnam, and to a new and different future in that country.

“The New York of the East”: Hong Kong Attractions

The structure of diasporic distribution of Chinese language video (film and television), and also some of the close intersections of Chinese media and its consumption by Indochinese in Australia, have been covered in Chapter 2. Coming at this intersection from the side of the Vietnamese communities, it is clear that, along with Vietnamese diasporic music video, the audiovisual product that is the site for most intense engagement is Hong Kong film and television. Compared with Hong Kong audiovisual influences, cultural anthropologist Mandy Thomas argues, Euro-American cultural influences are “almost insignificant” in Vietnamese-Australian households (personal email communication, 12 December 1996).

It is these two bodies of entertainment product that are drawn on as a series of (popular) cultural debates are played out in the overseas communities. Very lively cultural work—around the three axes of maintenance, adaptation/negotiation and hybridity; and perceptions of popular culture as frivolous and lowbrow on the one hand and affirmative and empowering on the other—is in play in Vietnamese engagement with both these sets of screen media. The tendency is for older, less educated people, and those with less English-language cultural capital, to embrace Vietnamese diasporic video and performance, particularly in their heritage maintenance role, and in their cultural negotiation role in terms of the middle-of-the-road production that forms the large majority of its output. Members of this same grouping are also consumers of Hong Kong television series, but not film. Vietnamese diasporic video is also strongly embraced by well-educated young adults as a form of contemporary cultural assertion—they are those members of the diaspora who most distinctively have created a fan culture around the product.

Young Vietnamese—particularly teenagers and boys, and to a lesser extent those who may have less education—embrace Hong Kong film on video as compatible with their particular youth culture. This may be influenced by the need to carve out cultural space away from the Vietnamese family unit and also because consuming Hong Kong product doesn’t require Vietnamese language skills (even if there are Vietnamese subtitles). This is a major form of cultural negotiation rather than hybridity—it creates space for a distinctive youth culture that is neither (traditional) Vietnamese nor Anglo and attracts, as Hong Kong action film does more generally (Wilson and Yue, 1996), dismissive rejection by mainland Chinese as well and can be used to mark out a space of rebellion from the expectations of cultural consumption for Vietnamese youth. Vietnamese diasporic music video can be eschewed by these same young men and boys as too embarrassingly middle-brow and “ultra-Vietnamese”, but also by many urbane professionals for exactly the same reason! The third position, that of assertive hybridity, is exclusively played out around Vietnamese diasporic music video and a small group of New Wave performers and their followings.

Most specialist East Asian video stores in Australia, whatever else they carry, stock Hong Kong television product from either of the main international suppliers, TVB or ATV—typically game shows, variety shows, and series and serials. Hong Kong action films also feature prominently. By volume of titles rented, television series are more popular amongst Vietnamese than feature films. There are a very small number of video titles sometimes available from Saigon television (through a small distribution company, Saigon Video), and some Taiwan movies are available subtitled in Vietnamese, but Vietnamese people prefer to watch TV shows or movies made in Hong Kong with Chinese actors and contemporary story lines. They tend to shun Vietnamese television on video due to poor production quality, outdated story lines and communist subtext. They feel anything that comes out of Vietnam will be, in the words of various informants, “vetted by the government” and therefore “contaminated with communist ideology”—or at the very least of inferior quality. No one who dismissed Vietnamese product for these reasons also regarded the Hong Kong product as being ideologically motivated. In this, they seem to share the general industry perception: “Born out of a competitive market with cultural laissez-faire, the serials are fast paced, melodramatic, apolitical and entertaining.” (Chan, 1996: 141)

These Vietnamese and Taiwanese videos do find a small niche market among older men and women who have been unable to learn English or adapt as well as Vietnamese in their forties or younger. These people have memories of Vietnam that predate the 1970s, and they tend to seek out Vietnamese folk tales or operas or Taiwanese television dramas which are set in a rural or village life, generally in a mythical past. They may even view Vietnamese television available through Saigon Video, just in order to see Vietnamese sets and actors. It is a phenomenon found by Naficy (1993: 42–43) among the Iranian exiles:

B movies and videos freeze fetishized images of Iran in the prerevolutionary periods, rekindling viewers’ nostalgic memories of their homeland and helping them to relive their experience of viewing films in Iran . . . they are viewed as souvenirs of an inaccessible homeland, irretrievable memories of childhood, a former prosperous lifestyle, and a centred sense of self.

Younger Vietnamese tend to be dismissive of this nostalgia for an unrecoverable or purely mythic past, and most Vietnamese families are more interested in Hong Kong long-form episodic drama as their soap opera fare of choice. Hong Kong, both the “imagined nation” and the media product, has been embraced—of course, not just by Vietnamese—as “the New York of the East”, an Archimedean space equidistant between West and East (for discussion of the absorption of Western influence into Hong Kong broadcast television, see Lee, 1991), an Eastern image of modernity between a denigrated/irrecoverable homeland and a Western setting in which they find themselves as an “Asian minority”. This material is consumed because it provides settings where Asian faces and values predominate. Certainly Vietnamese speak of Hong Kong as being culturally “other” to them, and this is usually spoken of in the context of being frequently perceived as socially inferior within Asian pecking orders—an experience ambivalently created or reinforced by many refugee Vietnamese spending their first long months or even years of “freedom” in Lantau, the huge refugee camp on Hong Kong territory.

But the appeal lies in the fact that they are not as “othered” in Hong Kong media as the white Western culture that they find themselves living in. Punning on geographical, as well as cultural, proximity, Thuy, a well-educated community worker and educator, said: “It’s close enough to Vietnam.” Interlocutors often claimed to like these videos simply because they didn’t have to struggle with language (for many, their Chinese language skills were adequate, together with irregular subtitling into English or Vietnamese). Clearly, though, the representation of Asians as hegemonic can be read as of equal appeal, particularly within Anglo host cultures where Asian peoples are still the subject of ongoing racist exclusion and attack. In viewing Asian videos, they are at least not being written out of existence, as is their experience in viewing Australian television.

Apart from these generic characteristics, there have been a number of Vietnamese characters, storylines and personnel in Hong Kong cinema and television. Producer and director Tsui Hark is Vietnamese, and has spoken of his thematic preoccupations being influenced by his status as a refugee and of the parallels between Vietnam under communism and the incorporation of Hong Kong into China—an allegorical but also political gesture regularly raised by Vietnamese fans of Hong Kong cinema and television. There are hero figures in features that are depicted as Vietnamese in origin, such as Mark in the cult films A Better Tomorrow 1, 2 and 3. Narratives about the plight of refugees are featured in, for example, Ann Hui’s The Story of Woo-Viet and Boat People, and there are films with characters based on the Ah-Chan persona, a refugee from Vietnam who is reunited with or adopted by Hong Kong relatives.

The most popular Hong Kong video material amongst Vietnamese falls into two distinct interest areas. One is in action adventure/martial arts; the other in family melodrama. Knowledge and interest in the first is found predominantly amongst boys and young men whose pleasure mainly derives from the representation of superhuman skills in martial arts. This aspect of Chinese tradition, like so much of it also very much part of Vietnamese culture due to millennia of Chinese cultural influence over and in Vietnam, is “owned” as their own culture through this sense of shared heritage, but also by being transformed into a contemporary generic “Asian” context.

The genre is characterised by stylised hyper-violence and by melodramatic, unequivocally heroic male characters. One Vietnamese male teenager interviewed suggested that these hero figures act very much as role models and fantasies about fathers who are now absent due to war or exile, or who have been rendered socially and professionally marginal, and therefore marginal in the family, within the host culture. And their textual violence was often sharply defended in sociological and psychological terms of the Vietnamese community having experienced social violence beyond that of the general Anglo population. Social violence, as well as textual violence, is often offered as a political allegory of anti-communism by young Vietnamese in trouble with the law (Smith and Tarallo, 1995; Thomas, 1996: 144).

The ambivalence of storylines such as that in the popular Hong Kong feature The Bodyguard from Beijing, where numerous references are made to the looming reunification of China and Hong Kong, can be read allegorically by Vietnamese as parallelling their quixotic opposition to communism while it inevitably continues in power in the homeland. Communist military discipline is pitted against Hong Kong’s laissez-faire Western consumerism and jokes are made at the expense of the Chinese police working for the British force. However, the Beijing bodyguard, in reprises of the Kevin Costner vehicle Bodyguard or Someone to Watch Over Me, triumphs in the end and achieves a kind of rapprochement between mainland and island.

Several of our interlocutors mentioned the burden of being the “perfect citizen” in the host country. (As Ghassan Hage argues in White Nation, the discourse of “worry” about the legitimacy, adaptability or disruptiveness of “Third World-looking” migrants is so pervasive that “If there is a single important, subjective feeling behind this book, it is that I, and many people like me, are sick of ‘worried’ White Australians” (Hage, 1998: 10).) They have experienced the effects of concerted media campaigns “worrying” about the community and their knock-on effects at street and community level, such as the killing of John Newman in Cabramatta (see Thomas, 1996: Ch. 6; Loo, 1994). “The entire Vietnamese community wears the brunt of this witchhunt,” said one respondent. Hong Kong cartoon-like hyper-violence allows a fantasmic space for boys and young men outside the often-crushing internal expectations of the Confucian family and the external expectations of a watching and worrying world.

More popular as family entertainment are Hong Kong television serials and series from TVB and ATV. These are limited-episode series requiring the viewer to rent episodes in order and screen them either over several consecutive nights or over, say, a month two or three nights a week. Each video typically has three episodes dubbed on to it. Both the form of this video rental and its content (television programming rather than feature films) are quite distinct from the typical patterns of mainstream rental, indicating that there is significant substitution of the broadcast television schedule by a video-constructed diet that provides a sense of the reliability and “dailiness” derived typically from a such a schedule.

European Australians normally rent movies on video once or twice a week; rental of television series or any other long-form release is very marginal. Video rental figures for 1996 provided by the Video Industry Distributors Association suggest 62 per cent of Australia’s VCR homes rent at least once a month with a minority of much younger “videoheads” renting up to six titles a week. However, the Asian video store proprietors and desk workers interviewed for this study confirmed that a characteristic of immigrant communities was high use of video. Several said it was not abnormal for customers to rent up to ten or more video cassettes a week, at least half of which contain three episodes per tape of a mid-run TVB or ATV series.

In a series of interviews and participant observations of family and individual rental and viewing of Hong Kong long-form fiction drama over recent years, shows like Before Dawn, Kindred Spirits, Nothing to Declare, Plain Love and It Runs in the Family—family melodramas from TVB or ATV, some subtitled in Vietnamese—were often mentioned as favourites. It Runs in the Family is a comic melodrama of a family separated by circumstance, and their attempts to reunite. The comedy is based on the fact that the twin brothers who were separated at a very young age actually live in the same household with the mother, their true relationship only perceived by the viewer. The mother and one brother continue to search for the other brother/son, even though he is already living with them as a boarder. An intruder answers an advertisement seeking the missing brother/son. The viewer’s frustration is amplified by this false brother’s claim to the family. The father is absent.

Participants spoke consistently of enjoying/identifying with the similarities between such a classic melodramatic narrative structure and their experiences of displacement and family fracturing. Looking back, the tragedies inherent in the often totally arbitrary nature of success or failure to keep families together during escape and relocation can be distanced through comic melodrama. Even the stock melodramatic trope of the false/assumed identity was woven in as memorable in terms of the need to dissemble or hide one’s own or loved ones’ identity under communism and/or in attempting to escape from it.

Almost without exception, participants spoke of the importance of familial ties and the difficulty of maintaining them in a host country that threatens established hierarchies and traditions. Marie Gillespie, in her discussions of television soaps, and particularly the use of Neighbours within the Punjabi community in Southall, emphasises the:

therapeutic effects of the mildly cathartic narrative resolutions to be found in soaps. Although many parents feel that their values are undermined by soaps like Neighbours, they can exploit the situation to reinforce traditional norms and values, or to renegotiate them with their children. Similarly, their children may affirm, or challenge, parental values around the TV set . . . In using and interpreting soaps, young people are constantly comparing and contrasting their own social worlds with those on screen. (Gillespie 1993: 31)

Like Gillespie’s teenage Punjabis, who creatively “misread” the household structures of the fictional universe of Neighbours as being like their own extended families in order to use the soap opera as a platform for working through issues of control and authority, so the stock melodramatic device of mistaken/misplaced identity in a family seeking reunification is “usefully” misread as a diaspora metaphor.

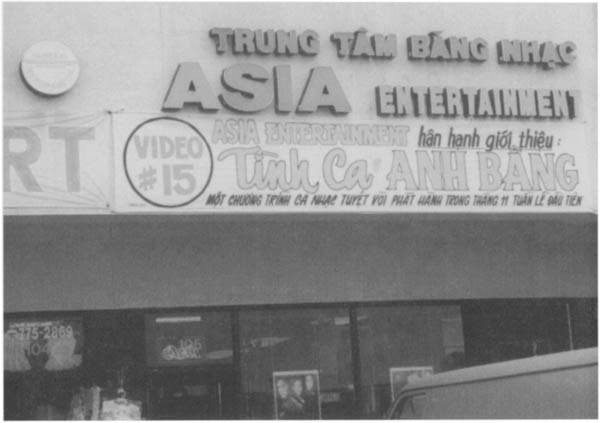

Vietnamese Diasporic Video

The live variety shows, and music video productions based on and arising from them, produced by Vietnamese-owned and operated companies based in Southern California and exported to all overseas communities, are the only media form unique to the diaspora as audiovisual media made by and for the diaspora. This media form is unlike the Croatian and Macedonian diasporic video analysed by Kolar-Panov (1997), which comprised amateur video letters. Nor is it of the same dimensions as that studied by Gillespie (1993), which was India-sourced video fiction or mainstream broadcast product. It certainly bears many similarities to the commercial and variety-based cultural production of Iranian television in Los Angles studied by Naficy, not least because Vietnamese variety show and music video production is also centred in the Los Angeles conurbation. The Vietnamese grouped there are not as numerous or rich as Naficy’s Iranians and so have not developed the extent of the business infrastructure to support the range and depth of media activity recounted in The Making of Exile Cultures. The business infrastructure of Vietnamese audiovisual production is structured around a small number of small businesses operating on low margins. It is, as Kolar Panov (1997: 31) dubs ethnic minority video circuits as they are perceived from outside, a “shadow system”, operating in parallel to the majoritarian system, with few industry linkages and very little crossover of performer or audience.

To be exilic means not—or, at least, not “officially”—being able to draw on the contemporary cultural production of the home country. Indeed, it means actively denying its existence in a dialectical process of mutual disauthentification (Carruthers, 1999). The Vietnam government proposes that the Viet Kieu (the appellation for Vietnamese overseas which carries a pejorative connotation) are fatally Westernised, whereas the diasporic population propose that the homeland population has been de-ethnicised through, ironically, the wholesale adoption of an alien (Western) ideology of Marxism-Leninism.

The widely dispersed geography and the demography of a small series of communities frame the conditions for “global narrowcasting”—that is, ethnically specific cultural production for widely dispersed population fragments centripetally organised around an officially excluded homeland. This makes the media—and the media use—of the Vietnamese diaspora significantly different from media consumption in the Chinese, Indian or Thai diasporas, which revolve around large production centres in the “home” countries.

These conditions also determine the nature of the production companies (Thuy Nga, ASIA/Dem Saigon, Mey/Hollywood Nights, Khanh Ha, Diem Xua and others). These are small businesses running at low margins and constantly undercut by copying of their video product outside the United States (particularly in Vietnam itself), where their ability to police copyright is restricted by not having the time or resources to follow up breaches. They have clustered around the only Vietnamese population base which offers critical mass and is geographically adjacent to the world-leading entertainment–communications–information (ECI) complex in Southern California. There is evidence of internal migration within the diaspora from the rest of the United States, Canada and France to Southern California to take advantage of the largest overseas Vietnamese population concentration and the world’s major ECI complex.

Conditions of Production

Thuy Nga Productions is by far the largest and most successful company. It organises major live shows in the United States and franchises an appearance schedule for its high-profile performers at shows around the global diaspora, and has produced more than 60 two-hour videotapes since the early 1980s (see Appendix 3.1), as well as a constant flow of CDs, audiocassettes and karaoke discs. President and owner of Thuy Nga, To Van Lai, was a university psychology professor before establishing Thuy Nga in 1969. Named after his wife, Thuy Nga was set up as a recording and production label which actuated To’s stance as a cultural intellectual bringing traditional folk and contemporary Vietnamese music traditions into contact with popular American and French music.

To Van Lai escaped with his family to Paris at the fall of Saigon, and continued to produce audiocassettes and to branch out into music video, CDs and karaoke output. The initial venture into music video was precipitated by To approaching a French TV executive in 1983 for assistance with making “a cultural exchange between the French and the Vietnamese”. According to To (1996), “the title of Paris By Night was chosen because during the day people worked hard with very little time, but in the evening they have more time for themselves. For anyone who has lived in France, there is nothing more beautiful than being in Paris at night; therefore the title Paris By Night was established.” Since then, at least two music videos have been produced each year (with current production at four annually).

A short history of the company was presented in 1998 on its fifteenth anniversary video (Thuy Nga Productions (hereafter TNP) 63, Paris By Night (hereafter PBN) 46—see Appendix 3.1). The early Paris By Night productions evoked pre-1975 Saigon through its revival of cabaret music and entertainment from previously well-established Vietnamese performers, such as Elvis Phuong, Jo Marcel and Khanh Ly. Due to the rising costs of production, more public demand for live concert performances in the United States and Canada, the demand for regularisation of music video production protocols, and the fact that the majority of Vietnamese performers were living in the United States, To moved Thuy Nga Productions to Orange County in the late 1980s. The first Paris By Night video produced in 1983 was recorded in Paris and cost about US$19 000. It consisted of eleven performances with local Vietnamese in Paris. In comparison, in the late 1990s, Thuy Nga releases at least four videos a year, consisting usually of 24 performances from a range of international Vietnamese performers, a stage and technical crew of approximately 300 people, often recording in front of packed audiences. Production costs per video have moved to US$500 000.

Paris By Night had the challenging task of breaking into the well-established demand for Chinese-language video in the United States, which “monopolised” the overseas Vietnamese market through the 1980s. Mostly Hong Kong product of the sort previously discussed, heavy consumption of multi-tape series television—indeed, according to To, the Vietnamese audience’s “addiction” to these series—had a deleterious effect on their working lives and their lifestyles. Within the wider issues of dealing with the new country, the contribution of “addiction” to Chinese videos worsened the community’s social dilemmas. To Van Lai’s attempt to provide an alternative to the Chinese language material began to work after 1986 when the release of its first special documentary edition, Gia Biet Saigon (Farewell Saigon), which is discussed below.

The revenue and profit generated from the live performances and shows helps to fund the production of music videos, CDs and karaoke discs. To Van Lai claims sales figures per video of approximately 40 000 and up to 80 000 for “specials” in the United States, but also states that overseas sales are not a significant or stable revenue source due to illegal dubbing of tapes. Income from overseas sales is a “bonus”: every country has its own laws on copyright and it would cost him more money to hire overseas lawyers to prevent piracy than to pursue the issue (To, 1996). Recent prices in US dollars are videos $25, CDs $15 and karaoke discs $85, with concert tickets ranging from $75 to $200. On these prices, Thuy Nga can count on about US$1 million in video sales in the United States alone, with costs of production for a single music video up to US$500 000.

Thuy Nga attempts to stay close to its audience by including a questionnaire in every purchased new release in the United States which requests information on favourite songs, who should perform them, and assessments of previous releases. Indicators of Thuy Nga’s success include the fact that mainstream advertisers are starting to place promotions in the videos and performers are prepared to work for free because of the worldwide recognition they receive. There are agents in the main population centres representing Thuy Nga Productions who franchise both the live shows’ organisation and the sales of video and other product from single master tapes sent from Southern California.

Apart from the artists, the regular Thuy Nga show comperes, Nguyen Ngoc Ngan and Nguyen Cao Ky Duyen, are both notable figures in the diaspora in their own right. Ngoc Ngan is a well-known political writer and novelist. After spending three years in reeducation camps from 1975 to 1978, he escaped to Malaysia by boat in 1979, and in that year completed his first novel while in the Malaysian refugee camp, Nhung Nguoi Dan Ba Con O Lai (The Women Left Behind). His first published work was The Will of Heaven (about his own personal journey as a refugee), written in English and published in New York in 1980. In 1992, Ngoc Ngan began his career as an MC for Thuy Nga. Nguyen Cao Ky Duyen’s father was former Republic Vice-President and Air Force Commander Nguyen Cao Ky. Her family fled the country in the 1970s while Ky Duyen was an infant.

The other most popular company committed to high production values is ASIA Productions (Dem Saigon/Saigon Nights) (see Appendix 3.1). It was established in the United States in the early 1980s. In contrast to Thuy Nga, ASIA is not a family business, but is owned by shareholders and run by a manager. ASIA reaches out beyond the established community performers, focusing more than Thuy Nga on promoting new talent in the United States and Canada. Through an annual “star search” competition, Truc Ho, ASIA’s music director, scouts for talent, offering contracts to perform live shows, video taping and CD recordings for the company. It also encourages its audience to take part in the “quest for stardom” by testing talent using its karaoke recordings, and then sending in tapes of the performances. Shortlisted singers are given the opportunity to perform in front of a live audience to get feedback on their performance. Like all other production companies, the main revenue and profit derives from the ticket sales of live shows and the domestic sale of CDs, videos and karaoke discs.

Other companies are not so popular, mainly because their productions are basic taping of live shows and do not enjoy the production values of the larger companies. MEY Productions (Hollywood Nights) is based in Westminster (as are all these companies) and established itself in the early 1990s with a series of “Hollywood Nights” videos conspicuously patterned on the successful Paris By Night formula. Mey’s emphasis is less on stand-alone music videos as the company also focuses on producing Van Nghe Vietnam (Vietnamese Entertainment), a regular program on the local community-access television station. These smaller concerns must look further afield for their talent, as Thuy Nga and ASIA tend to sign the well-known, popular performers.

Khanh Ha Productions is a family-controlled business. The father, Lu Lien, a popular composer and singer from the famous singing trio AVT, is of the same generation as composer Pham Duy, who just happens to be an in-law (Lu Lien’s son, singer Tuan Ngoc, is married to singer Thai Thao, who is the daughter of Pham Duy). Khanh Ha and her siblings (Tuan Ngoc, Anh Tu, Luu Bich, Lan Anh, Thuy Anh and Bich Chieu) and other performers are a close-knit group performing live regularly in their family-owned night club, recording CDs and producing occasional music videos.

Conditions of Consumption

From data supplied by the production companies and distributors, the rates of sale and rental derived from samples of video store retailers, and the scale of attendances at regular live variety performances, it can be surmised—in the absence of large-scale tracking surveys for which the industry does not have resources—that most overseas Vietnamese households may own or rent some of this music video material, and a significant proportion have developed comprehensive home libraries. Its popularity is extraordinary, cutting across differences of ethnicity, age, gender, recency of arrival, refugee or immigrant status and home region. It is also widely available in pirated form in Vietnam itself, as the economic and cultural “thaw” that has proceeded since Doi Moi policies of greater openness has resulted in extensive penetration of the homeland by this most international of Vietnamese expression. (Carruthers (1999) points to data from 1996 which estimates that 85–90 per cent of stock in Saigon’s unlicensed video stores was foreign.) As the only popular culture produced by and specifically for the Vietnamese diaspora, there is a deep investment in these texts by and within the overseas communities—an investment by no means homogeneous but uniformly strong. The social text which surrounds—indeed, engulfs—these productions is intense, multi-layered and makes its address across differences of generation, gender, ethnicity, class and education levels, and recency of arrival. “Audiovisual images become so important for young Vietnamese as a point of reference, as a tool for validation and as a vehicle towards self identity.” (Trang Nguyen, 1997)

The central point linking business operations, the textual dynamics of the music videos and media use within the communities is that what we have called the three cultural positions or stances in the communities, and the musical styles which give expression to them, have to be accommodated somehow within the same productions because of the marginal size of the audience base. From the point of view of business logic, each style cannot exist without the others. Thus the organisational structure of the shows and the videos, at the level both of the individual show/video and at the level of whole company outputs—particularly those of Thuy Nga and ASIA—reflects the heterogeneity required to maximise audience within a strictly narrowcast range. This is a programming philosophy congruent with broadcasting to a globally spread, narrowcast demographic.

This also underscores why “the variety show form has been a mainstay of overseas Vietnamese anti-communist culture from the mid-seventies onwards” (Carruthers, 1999). In any given live show or video production, the musical styles might range from pre-colonial traditionalism to French colonial-era high modernist classicism, from crooners adapting Vietnamese folksongs to the Sinatra era through to bilingual cover versions of Grease or Madonna. Stringing this concatenation of taste cultures together are the comperes, typically well-known political and cultural figures in their own right, who perform a rhetorical unifying function:

Audience members are constantly recouped via the show’s diegesis, and the anchoring role of the comperes and their commentaries, into an overarching conception of shared overseas Vietnamese identity. This is centred on the appeal to . . . core cultural values, common tradition, linguistic unity and an anti-communist homeland politics. (Carruthers, 1999)

Within this overall political trajectory, however, there are major differences to be managed. The stances evidenced in the video and live material range on a continuum from “pure” heritage maintenance and ideological monitoring, to mainstream cultural negotiation, through to assertive hybridity. Most performers and productions seek to situate themselves within the mainstream of cultural negotiation between Vietnamese and Western traditions. However, at one end of the continuum there are strong attempts to keep both the original folkloric music traditions alive and also the integrity of the originary anti-communist stance foundational to the diaspora through very public criticism of any lapse from that stance. At the other end, Vietnamese-American youth culture is exploring the limits of hybrid identities through “New Wave”, a radical intermixing of musical styles. We shall consider some textual examples of each style and audience/readership responses to them.

Heritage Maintenance

Heritage maintenance, as we have seen in relation to newspapers, embraces a range of cultural and informational production and is closely connected to the ideological monitoring role of maintaining the salience of the anti-communist stance foundational to the diaspora. Diasporic video is one of the prime sites monitored. This is borne out spectacularly in the Mother issue of Paris By Night (PBN 40). Paris by Night 40 was released in 1997 to coincide with Vu Lan, the Season of Filial Piety, a time for special veneration of parents. The video was particularly popular, but popularity turned to condemnation in the diaspora when it was discovered that a small segment of documentary war footage showing planes strafing and killing South Vietnamese civilians was actually of the Republic of South Vietnam (RSA) air forces. Thuy Nga asserted it was the innocent mistake of a young and inexperienced editor; both To Van Lai and compere Nguyen Ngoc Ngan were forced to publish apologies in the main newspapers and calm very angry responses on Websites, in letters to the editor, on radio and in demonstrations outside Thuy Nga’s offices. Some even alleged that it was a cynical ploy by the company to establish its good name in Vietnam in advance of a greater entrepreneurial effort in the homeland.

The Mother imbroglio has been extensively analysed by Carruthers (1999), who stresses the porosity of communications flows between the diaspora and the homeland, noting that the degree of ideological border-drawing on which the identity and integrity of both the homeland regime and the diasporic community depend is increasingly difficult to sustain under the pressures of globalisation. However, it is appropriate for our themes that we stress that the Mother episode illustrates the degree of psychic and ideological investment in the music video corpus and the degree to which it, like all public cultural manifestations, is monitored for deviations from the ideological foundations of the diaspora. The social text of the corpus is subtended by strong community expectations of a proper education for the young in the reasons for cultural maintenance. While much of the dissolution of boundaries between homeland and diaspora proceeds around cultural product, entrepreneurship and travel (it was estimated that about 20 000 Australian Vietnamese visited Vietnam annually in the mid-1990s), there continues to be organised resistance to such dissolution among the overseas populations. Examples include boycotts of restaurants run by government-aligned owners, and the fact that a new shopping complex, known as the “cultural court”, in the heart of Westminster on Balsa Avenue that was part-financed by the homeland sources was conspicuously under-patronised—and for a good time virtually boycotted—in the months following its opening in 1996. International attention was drawn in 1999 to the community attacks on a shop owner in the precinct who insisted on flying the official country flag and displaying pictures of Ho Chi Minh.

The main musical expression of heritage maintenance lies in the restoration and preservation of traditional Vietnamese music styles (and the instruments on which they are played). Major cultural figures such as Pham Duy, often titled in American media coverage as the “Woody Guthrie” of Vietnam, have devoted long careers to the maintenance of the received Vietnamese heritage in folk culture. (He wrote a historical treatise, Musics of Vietnam (1973); has had several special issue videos dedicated to his corpus; and has recreated as a folk opera the “Iliad of Vietnam”, Truyen Kieu (The Tale of Kieu).) The purity is maintained through a scholarly attention to the traditions and their transmission to a younger, dispersed generation; the artisanal attention to the playing of traditional Vietnamese musical instruments; but also a preparedness to transmit this heritage by contemporary technologies such as CD and the Internet. Into this category should also be placed a considerable amount of traditional folk balladry and a residual element of traditional Vietnamese opera on the tapes. This form of “pure” heritage maintenance is clearly mainly consumed by the older generation of the educated elite.

A small fraction of the music video corpus is given over to heritage maintenance across the entire tape. These six to eight tapes are constructed quite differently to the rest and are at the other end of the stylistic continuum from the live show formats. They are compilation documentary-style video, and have been produced typically to commemorate historical anniversaries in the overseas communities’ lives (examples include TNP 41, 10th Anniversary; TNP 32, 20 Nam Nhin La (Looking Back 20 Years), Asia 7, 1975–95).

An early example of the historical compilation video is Thuy Nga 10 Gia Biet Saigon (Farewell Saigon). Made in 1986, this Thuy Nga production has none of the sophisticated production values and choreography of later productions; in fact, it is organised on quite different principles to the variety show format of most of the corpus. The organisational principle is one of popular memory, bearing all the hallmarks of a very specific address to the military, educational, business and government elites of the South Vietnam regime in the period leading to the fall of Saigon.

This principle of organisation makes it a virtually unwatchable tape for all but this specific audience. The great majority of second-generation and recent arrivals who participated in focus groups and interviews asserted that historical compilation material was “for [their] parents” or for those who “had been through the events” being recounted. Farewell Saigon, a tape of approximately 90 minutes’ duration, comprises historical footage of pre-1975 Saigon (together with some post-1975 footage) with studio-based musical interludes sung by profiled performers of the same or similar generation to the target audience—those performers who successfully transitioned from pre- to post-1975 as part of the diaspora.

The great majority of the elapsed time on the tape is a video essay extolling the strength, social balance and harmony, and dynamism of a well-governed and stable Republic of Vietnam during the Diem and Thieu years. So much can be readily deduced from the contents and organisation of the tape. What can be adduced from its reception and use within the specific target audience—the original diasporic elites—is both the depth of loss and longing which the tape engenders and, on the other hand, a still-strong politics of disavowal of the regime’s complicity in its own downfall and the continued placing of blame on America as a “great and powerful friend” which withdrew its support unilaterally, rendering the defence of the republic impossible. The vertiginous shifts from triumphalism to abjection, from very long static camera angles on impeccably suited parades of military to the hand-held chaos of the end-time of 1975, has strong parallels with the abrupt changes of tempo and testamental nature of the Croatian video analysed by Kolar-Panov (1997: 153).

The footage combines travelogue-style panoramas of market scenes, major downtown buildings, the Presidential Palace, main girls’ and boys’ schools and a compendium of a religious buildings. The second set of visual materials include a highly structured, syncopated visual hymn to the women of the republic, cut to complement the ballad “Co gai Viet” (The Vietnamese Lady) in a studio setting by three women performers wearing signifiers of North, Centre and South regions of a pre-communist-unified country. The third type is very extensive footage of a military parade that was held on 26 October, the National Day, each year. Voiceover commentary details the different regiments in careful detail and occupies almost half an hour of the tape.

What is readable as flat “propaganda” and inexcusably tedious editing by its non-intended audience is received very differently by its primary audience, the original diasporic elites. For them, Farewell Saigon is like a home movie. There are no specific time references to anchor the footage at a particular date apart from its ambience in the later 1960s/early 1970s: it inhabits a modality of popular memory, with very specific anchors of place but not of time. In one family with whom researchers were invited to watch the video, the father had been an RSA fighter pilot and had been interned in a re-education camp for eleven years before being allowed to come to Australia under the family reunion program. Farewell Saigon has footage of his military unit which he finds impossible to watch. The mother can point out the school she went to as a girl—the images of a sea of white ao dai (traditional dress worn by Vietnamese women) spreading gaily from the gates of the school are images of Confucian educational rectitude and the innocence of youth that are almost equally impossible to watch.

There are also those for whom the politics of this tape are to be foregrounded: “The video brings back emotional memories of how proud and honoured Vietnamese should be with their country and not believe false propaganda and damaging accusations by foreign political analysts and the Vietcong” and “It was produced to remind the Vietnamese and the rest of the world that Vietnam was once an independent nation until it was betrayed in the war by its American allies” are representative of the public construction that can be placed on this material by its intended audience. It is important to note that there is nothing in the tape commentary or visuals that directly attacks the United States—but there is a studied absence of virtually any signifier of what was by the time of the footage an overwhelming American presence in Saigon.

There is also a very direct political sense in which Farewell Saigon is like a home movie. Most of the documentary footage used in the video was smuggled out of the country just before the fall of Saigon by the Vietnamese Student Association in Paris. It was then handed over to a senior military figure who gave To Van Lai copyright clearance to use the footage in his assembly for Gai Biet Saigon. The footage is a virtual palimpsest of the violence of exile—such media, left behind after the fall of Saigon, would have had prime value in targeting elite members of the fallen regime.

Cultural Negotiation

The auspicers of the inevitable and widespread negotiation between Vietnamese and Western cultural forms are prominently the owners of the small-business music video production houses and the principal well-established performers. Many of these figures were prominent in South Vietnamese cultural production before 1975 and have maintained that position in the ensuing decades. They are educated in the heritage and have maintained the popular memory as they simultaneously auspice inevitable hybridisation of this heritage under the commercial imperative. But this is to continue a well-established historical hybridisation. For the most established, there are direct links back to pre-1975 Saigon, and the continuities of such converged music forms being developed and practised well before 1975 need to be accounted for. The hybridity of Vietnamese music culture has its roots both fundamentally in millennial Chinese–Vietnamese interchange and more latterly with French interchange during the colonial period. In the 1960s, it was the massive influence of American rock and roll during the war, especially in Saigon, which provided the most recent pre-exile infusion of hybrid elements. Pham Duy’s historical treatise Musics of Vietnam (1973), even as it is committed to the identification and preservation of the country’s folk traditions, shows that the south’s major styles of theatrical romanticism in performance, while influenced by French and latterly American traditions, was originally a Chinese influence (1973: 118). As was observed in Chapter 1, Vietnamese area studies could benefit significantly from a greater sense of the mutability and adaptability of its object of study, and this is nowhere clearer than in the area of popular culture. Terry Rambo (1987), arguing this case, shows that even such an exemplary symbol of Vietnamese authenticity, the ao dai, is a borrowing from Chinese culture.

Of the cultural positions available to the communities, that which accepts the inevitability of cultural negotiation and adaptation and fashions musical styles around that position seeks to minimise the more liminal postures of heritage maintenance or assertive hybridity. The musical styles are mainstreamed and stable in style, based on established patterns of intermixing Chinese, French and US inputs from before 1975. A major figure, Elvis Phuong—an Elvis cover singer before it became a global industry!—was an established performer in Saigon before 1975 and his career has continued unabated throughout the exile. Other major performers include Luu Bich, Tuan Ngoc and Khanh Ha. Befitting its mainstream status, probably two-thirds of the corpus is of this type, as it is predominantly easy listening or middle-of-the-road “crooner” presentational styles that are the least confronting and of potentially broadest address across audience interests. The style of music renews audience connections to the soft melodic music and sentimental ballads often performed in bars and cabarets of the pre-1975 period. Visually, this style of presentation rarely employs documentary footage characteristic of the first style, nor does it involve the elaborate postmodern-pastiche stage settings and “excessive” costuming of the third style. All the companies aim for this type of predominant content, as it will maximise its target audience. The other two categories occupy together roughly a third of total output.

“Hat Cho Ngay Hom Qua” (Song of Yesterday) (TNP 37, PBN 20, 1993), a “Lien Khuc” (medley) with performers Elvis Phuong, Duy Quang, Anh Khoa and Tuan Ngoc, is a good example. Performed bilingually, the medley comprises popular Western songs of Elvis Presley and John Lennon, and music from the era of the Vietnam War (“Yesterday, all my troubles seemed so far away, now it looks as though there’re here to stay, oh I believe in Yesterday”/“Yesterday when I was young”/ “And now the time is near and so I face my final curtain”/ “When the night has come and the land is dark and the moon is the only light we’ll see, no I won’t be afraid, no I won’t be afraid, just as long as you stand, stand by me”). The performance draws upon the memories of the mature audience who lived in Saigon throughout the 1950s to 1970s—hence the title: “Hat Cho Ngay Hom Qua” (Sing for Yesterday). That audience’s memories of an era of continual war, struggle and devastation are mapped gently on to the “hardships” which are the thematic substance of the original Western songs (lost and unrequited love, etc.) and the massive disjunction is managed in the ambience of nostalgia and tasteful dinner jackets on the set.

Innovation within this style is centred on harmonious both-ways adaptation: Vietnamese interpretation of foreign music or traditional Vietnamese lyrics with the influence of contemporary Western music. New songwriters like Nhat Ngan and Khuc Lan specialise in translating and interpreting Chinese and French songs into Vietnamese New Wave music. Luu Bich is often linked with the latter, performing a wide range of Chinese ballads translated into Vietnamese with one of the most popular song being “Chiec La Mua Dong” (The Leaf of Winter). Composers like Van Phung and Ngo Thuy Mien, for example, are strongly influenced by jazz and rhythm and blues. In “Noi Long” (Feelings) (TNP 56, PBN 39, 1997), Bich Chieu’s performance of lyrics which are purely Vietnamese is revamped with a Western influence of jazz and blues. The initial reaction from one focus group of young recently arrived school students watching this was that it was “weird” and “un-Vietnamese”. However, during discussion and reflection, they were able to appreciate the new version of the song.

The most productive means of grasping the cultural work audiences are performing with this music is to see it as positively modelling identity transition. The simple lyrics, well known to the point of cliché (“easy listening”) in Vietnamese, English or French, provide a reassuring point of recognition for those (mostly the older, more recently arrived) who find themselves displaced in an overseas community where language is the main cultural barrier; while others (mostly the young) are provided with an easier way into understanding their own family’s cultural environment. ASIA Productions specialise in this approach. Thanh and Jasmine, well-educated relatives who are dedicated fans of the music, reflected that they were initially attracted to their own heritage by their interest in the re-mixing of traditional folklore music through the music videos of ASIA Productions.

The cultural negotiation position can also be distinguished politically from heritage maintenance insofar as it is prepared to negotiate certain emergent relationships with the homeland—a stance unthinkable within the first category. As Carruthers (1999) points out, the revered composer Trinh Cong Son, who actually lives in Vietnam but enjoys equal popularity both at home and abroad, has had a long collaboration with popular diaspora singer Khanh Ly. Also, diaspora artists are now beginning to test the home market with some live performances, such as at the major Tet celebrations since 1996. Indeed, there is greater reciprocity to this emergent and problematic rapprochement than might at first appear:

The homeland pirate culture industry has been able to take advantage of lax copyright and censorship laws to enjoy the fruits of overseas Vietnamese media companies’ labours without contributing to their revenues, while overseas companies have been able to exploit the first world/third world divide by going to Vietnam to record the voices of local singers, mastering them in studios back in France and the US, and releasing the CDs at a significantly lower price than those produced entirely overseas. (Carruthers, 1999)

“New Wave” Assertive Hybridity

While the hybrid retains its links to and identification with its origins, it is also shaped and transformed by (and in turn, shapes and transforms) its location in the present.

Belonging at the same time to several “homes”, it cannot simply dissolve into a culturally unified form. The complex achievement of the hybrid is a product of [the] obligation to “come to terms with and to make something new of the cultures they inhabit, without simply assimilating to them”. The result is a celebration of cultural impurity, a “love-song to our mongrel selves”. (Turner, 1994: 124–25, internal quotes Hall, 1993: 362)

The reception for performers who assertively seek to fully appropriate Western rock and pop (in a style that is dubbed “New Wave”) can be as intense as the political controversies around incidents such as the Mother episode. This “assertive hybridity” is exclusively a phenomenon of youth culture, and centres on its very specific formation at “ground zero” in Southern California. The “excesses” of controversial performers such as Lynda Trang Dai, Nhu Mai, The Magic or Don Ho have some precedent within the context of Californian Vietnamese-American youth culture (as evidenced by the specialist lifestyle magazines for Vietnamese-American young people such as Viet Now). However, the economics of live performance and music video production necessitate a much broader audience and thus a context beyond its niche age and style demographic.