CHAPTER 2

ETHNIC DIVERSITY OF NORTH-EAST INDIA

CONTENTS

2.3 Tribes of Arunachal Pradesh

ABSTRACT

The North Eastern (NE) region of India houses considerable ethnic multiplicity, which largely differ in their traditions, customs and language. Majority of these tribes are forest dwellers and live in communities under the rule of despotic chiefs. These tribes are classified according to their origin, language, race, religion and their geographical location. These tribal communities are distinct from each other and considerable variations are found even among closely related tribal groups of the region. In this chapter, we focus on the different ethnic communities of NE India, their distribution, their cultural activities, religion and languages.

2.1 INTRODUCTION

India is a multicultural country and perhaps nowhere in the world people in a small geographic area are distributed as a large number ethnic, caste, religious and linguistic groups as in India (Bhasin and Walter, 1994). People of different groups live side by side for hundreds or even thousands of years but yet retained their support entities through endogamy. These diverse groups of people started migrating to India from different directions in an unbroken sweep over at least 5,000 years from the present and have contributed very significantly to the present day rich human gene pool of the sub-continent (Gadgil et al., 1998; Allchin and Allchin, 1982; Sankalia, 1974; Misra, 1992; Kashyap et al., 2003). The diverse ecological regimes of India seems to have nurtured this diversity (Gadgil and Guha, 1992). The major waves of historical migration into Indian sub-continent include Austro-Asiatic languages speakers soon after 65,000 BP, probably from the Middle East, Indo-European language speakers, in several waves, after 4,000 years BP and Sino-Tibetan language speakers, in several waves, after 6,000 years BP (Gadgil et al., 1998). The ethnic racial groups of India include the Caucasoid, Negrito (or Negroid), Australoid and Mongoloid who differ from one another in certain morphological features, but one should remember that there are no strict lines of demarcation between these four racial groups. The first and last racial groups are mainly concentrated in the north and northeastern parts of India, the third confined mostly to central, western and southern India while the second is essentially restricted to Andaman Islands (Cavalli-Sforza et al., 1994). The linguistic groups of India include the Dravidian (Dravida), Austro-Asiatic (Nishada), Tibeto-Burman or Sino-Tibetan (Kirata) and Indo-European (Indo-Aryan). They together speak about 187 languages and 544 dialects. The first group is spread essentially over southern part of India, the fourth essentially over northern part of India, the third essentially over northeast India, while the second is restricted to certain tribes such as Korkus, Mundas, Santals, Khasis and Nicobarese (Kashyap et al., 2003). The People of India project recognized 4635 distinct communities in India, although the actual number of endogamous groups may be of the order of 50 to 60 thousand (Cavalli-Sforza et al., 1994; Singh, 1998). The religious groups of India include, Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsi and Jews.

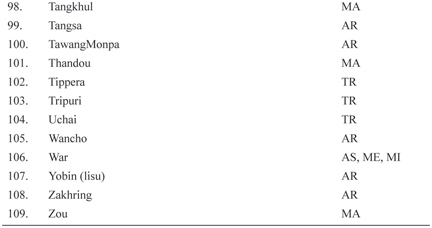

The northeast region of India is a very important region known for its cultural heritage, rich floristic and faunal diversity, diverse ethnicity and unique biogeography. It is located in the North eastern corner of India comprising of eight states/ territories of Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura and Sikkim. It comprises 8% of the total land size of India. According to the census of 2001, the total population of North East India is approximately 40 million (2011 census), representing 3.1% of India’s total population. This region borders on China and Bhutan in the North, Myanmar in the east, Bangladesh and West Bengal on the West and the Bay of Bengal of the South. It is connected to the mainland of India with a 22 km long “Chicken Neck corridor (Bijukumar, 2013) or Siliguri corridor. Although this region shows ecological and cultural contrasts between the hilly terrains and the plains, there are significant features of continuity (Kumar et al., 2004)(Kumar et al., 2004). Interdependence and interaction (Dutta and Dutta, 2005). With more than 150 tribes speaking as many language, the northeast region of India is a “Melting pot of variegated Cultural Mosaic” of races, languages, religions and “ethnic tapestry of many hues and shades” (Dutta and Dutta, 2005). This chapter deals with ethnic diversity of northeast India and the rich cultural diversity associated with it.

2.2 ETHNIC DIVERSITY

The tribal segment of Indian population reflects an interesting profile of India’s ethnic richness and diversity. There are about 427 tribal communities all over India, of which about 145 major tribal communities and a total sub-tribes of 300 (Kala, 2005) are found in northeast India. It has been estimated that of the approximately 40 million people inhabiting this region, around 10 million are tribal or 25% (Ali and Das, 2003).

The first settlers of North East India were Austro-Asiatic speaking people and later people of Tibeto-Burmese and Indo-Aryan origins settled there. It is the home for major tribal communities like Abor, Garo, Khasi, Kuki, Naga, Apatani, Adi, Hmar, Mizo, Reang, Chorei, Tripuri, etc. Studies have indicated that due to immense biological and crop diversity and availability of fertile land, the primary tribal settlers were mostly farmers although they were preceded in some parts by hunter-gatherers/foragers. The major tribal groups are of Mongoloid origin, who came to the region at different times, possibly earlier than Caucasoid (Das et al., 1987; Kumar et al., 2004). The tribes that belong to the Mongoloid racial stock usually belong to the Tibeto-Chinese or Tibeto-Burmese linguistic family, while the Caucasoid are related to Indo-European linguistic stock (Kumar et al., 2004). Both Mongoloid and Caucasoid represent definite degree of differences in cultural and biological traits. Some workers have suggested that the Australoids came to North East India before the Mongoloids and the physical feature of different tribes of this region suggests the presence of Australoid element in some of the tribes (Das, 1970; Ali and Das, 2003). The diversity of tribal communities varies considerably. In Assam, Tripura and Manipur, the tribal communities represents 12.82%, 30.95% and 34.41% respectively of the total population, while ~90% of the total population in other states are represented by tribal communities.

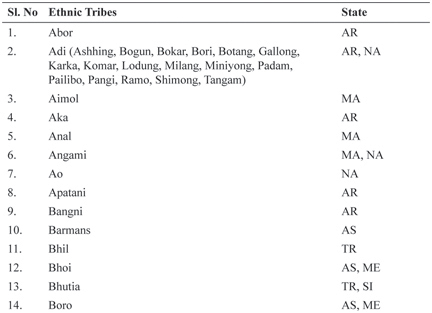

The most important tribal communities in the various states of northeast India are shown in Table 2.1. It is evidenced from this table that among all the major tribes of North East India, the largest groups comprise the Bodos, Khasi, Garo, Naga, Mizo, Karbis and Mishing. The Bodo tribes are widely distributed from areas bordering North Bengal to the western Nagaon and Darrang districts of Assam, while Khasi and Garo have well defined homeland in the state of Meghalaya. Mizo are characteristically found in the state of Mizoram, while a small population is also residing in some parts of Southern Assam (Cachar district) and regions of Manipur. Karbi tribe belongs to the Karbi-Anglong district of Assam but also spread over some parts of Dima-Hasao district in Assam and parts of western Nagaland and north-eastern Meghalaya. In Nagaland, the major tribal communities include the Ao, Sema, Konyak and Angami. Bulk of the Naga population belonging to Tangkhul, Kabui and Thado are found in the state of Manipur. Hmar tribal population is widely distributed in states of Manipur and Mizoram, while a major population is also found in three districts of Southern Assam. In Arunachal Pradesh, the major tribes include the Nishi, Apatani, Adi, Mishing, Wancho and Galong. These tribes represent extreme heterogeneity in terms of population distribution and socio-cultural structure and pattern (Ali and Das, 2003). Each of the tribe has distinct sub-divisions and their customs and societal structure varies considerably. For examples, among the sub-divisions of Khasis like Wars, Khynriams, Pnars and Bhois follow distinctive the socio-cultural traits, which varies considerably with each other (Ali and Das, 2003). The geographical distribution has a strong impact on social, cultural and economic aspects of each of the tribes. The Dimasa-Kacharis residing in Dima-Hasao district of Assam have mostly retained their traditional practices, while those living in Cachar district have a strong influence of Bengali culture and customs. Most of the tribes which are in vicinity of non-tribal groups are mostly influenced by the non-tribal customs and in due course of time they have acquired such customs and culture in their day to day life (Ali and Das, 2003). The diversity of the cultural heritage gives the tribal communities of North East India their specific identity. The North Eastern region of India, which is represented by bulk of the tribal population of the country have cultural and traditional similarities with inhabitants of China, Tibet and Myanmar. After the post-independence era, these tribal communities of North East India have faced identity crisis and as a result there is a strong divergence of these communities towards modern life. Further, loss of traditional cultural among the tribal youths has also resulted in loss of traditional knowledge and heritage. This situation appears to be extremely alarming and needs special attention to conserve the precious traditional knowledge.

Key: AR – Arunachal Pradesh; AS – Assam; MA – Manipur; Me – Meghalaya; MI – Mizoram; NA – Nagaland; SI – Sikkim; TR – Tripura.

The culture of North-East Indian Tribal communities is reflected in their food, dance, music, drama, festivals (including harvest, pottery), arts and crafts, songs, dressing, jewelry and ornaments, tattooing, and social ceremonies and rituals, which vary in different communities. The most important festivals celebrated are Nyokam, Ngada, Kashad Suk Nongkrum, Mimkuut, Khaskain, Wangala, etc. Their arts and crafts include weaving (cotton, silk, and wool) with different motifs printed (manual) using vegetable dyes, crafts and furniture made out of canes, bamboo and wood, basket weaving (using canes and wild twinners and climbers) etc. The major dance forms include Ponung, RekhamPada, Ajima Rao, and Chambilmpa when string and wind blowing instruments.

TABLE 2.1 Major Ethnic Tribes of Northeast India

2.3 TRIBES OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH

The tribal of Arunachal Pradesh constitutes 64.20% of the total state population. There are 35 ethnic groups in the state, which are widely distributed in 13 districts. Almost 86% of the tribal population thrives in rural areas with farming and animal rearing as their principal occupation. Among the tribes, the female population exceeds the male population in the state. The tribal population of Arunachal Pradesh is of Asiatic origin and have facial proximity with people of Tibet and Myanmar. In the western part of Arunachal Pradesh, the major tribe include Nishi, Sulung, Sherdukpen, Aka, Monpa, Apatani and Miri. Adis are one of the largest groups in the states after Apatani, which occupies the central region of the state. The Wancho, Nocte and Tangsa are mainly distributed in Tirap district, while Mishmis are mostly concentrated in northeastern hills. These groups differ among themselves in their culture, tradition, customs and religious beliefs. There are almost 50 different languages and dialects. Majority of the languages spoken by these tribes belong to the Tibeto-Burmese branch of Sino-Tibetan language family. Beside their own language, the tribes are well conversant in English, Hindi and Assamese. Mompa tribe has six subgroups, which include the Sherdukpens, Akas, Khowas and Mijis that are inhabitants of Kameng district. In the east Kameng district, Sulungs, Mijis and Akas are the pre-dominant tribes. Among Adis and Tangsas, there are about 15 sub-groups, while Mishmis are divided into 3 sub-groups. The Mishmi tribes are distributed mainly in the Dibang valley and Lohit district of Arunachal Pradesh. In addition to the Mishmis, the Lohit district is also inhabited by other tribes including Zhakrings, Meyors, Khantis and Khamiyangs (Ali and Das, 2003). The main religious practices among the Arunachal tribes is based on worshiping the deities of nature and spirits. Ritual sacrifice of animals like Mithun is commonly observed among all the major tribes of Arunachal Pradesh. Religious beliefs based on Hinduism and Buddhism can also be observed among several tribes of the state.

2.4 TRIBES OF NAGALAND

Nagaland has around 30 ethnic communities. The Naga tribe of North East India is one of the most diverse tribal communities of India. In the 1991 census of India, there are 35 different Naga tribes that are enlisted among the schedule tribes in India, out of which 17 in Nagaland, 15 in Manipur and 3 in Arunachal Pradesh. Each of the tribal inhabited regions of Nagaland has its own definite population and usually governed by despotic chiefs. The current geographical regions of Nagaland comprises of some former Naga districts of Assam and Tuensang frontier divisions. It is divided into eight main districts viz., Mokokchung, Tuensang, Mon, Wokha, PhekZunheboto, Kohima and Dimapur. The most predominant Naga tribes include the Angami, Ao, Chakesang, Chang, Chirr, Konyak, Lotha, Khiamngam, Makware, Phom, Rengma, Sangtam, Sema, Yimchunger and Zeliang (Ali and Das, 2003). Each of these tribes have their own legend, which articulates about the original course of their migration. The Khaimungan, Pochury, Sangtam and Chang regard themselves as original descendants of Naga Hills, while Angami, Chakhesang, Lotha, Rengma and Sema have originated from same racial stock but got separated and congregated their own identity. However, conflicting views regarding their origin and ancestry exists. It is assumed that larger tribes like the Ao and Angami kept on shifting from one place to another and gradually encroached into territories of smaller tribes, but later due to economic and social compulsion they started settling into specific territories and maintained principles of patrilineal descent. Smaller group of Naga tribes like Kahha came from Phom, which in their local dialect means cloud. Pochury, which is the smallest group among all Naga tribes have originally descended from the Chakhesang tribe and widely distributed in about 24 villages of Nagaland. People of Pochury tribe are engaged in spinning, carpentry, stone craving and leather works. The Rengma are divided into two distinct territorial groups’ viz., Nteyne and Nzong, which occupies the subdivisions constituting Nidzurku Hills to Wokha Hills. Both Nteyne and Nzong groups of Rengma tribe have different dialect. It is also believed that a major section of Rengmas have gradually migrated to the Mikir Hills in Assam. The Yimchunger is a relatively small group of Naga tribe that is divided into three sub-tribes viz., Tikir, Makware and Chirr. They speak different dialect and live in a well-defined territory under the headship of tribal chiefs. The Sangtams of Nagaland are divided mainly into two distinct territorial groups in Chare and Kiphire sub-divisions of Nagaland. Sema is widely scattered in almost in all major parts of Nagaland and also distributed in some parts of Assam. The Zemi, Liangmei and the Rongmai belongs to single ethno-cultural entity and collectively known as the Zeliang in Nagaland. Among the Naga, there is no concept of caste or class. Each clan is exogamous, which occupies a definite territorial boundary. The clans have their independent political and economic rights and distinguishes itself from the other in terms of the custom, language and ethnicity.

2.5 TRIBES OF MANIPUR

The state of Manipur is distinctly divided into two geographical regions. This includes the fertile plains and hilly tracts. Manipuri belonging to the Methai community are the primary inhabitants, however, tribal groups belonging to Naga and Kuki-Chin-Mizo are also the native of Manipur. As per the 2001 census, Manipur comprises of 34.2% tribal population, under about 30 tribes the total tribal population of Manipur, Thadou is considered as the largest with a total population of1.80 lakhs, representing 24.6% of the total tribal population. Other major tribes of Manipur include Tangkhul (19.7%), Kabui (11.1%), Paite (6.6%), Hmar (5.8%), Kacha Naga (5.7%) and Vaiphui (5.2%). Other major tribal groups of Manipur are Maring (3.1%), Anal (2.9%), Zou (2.8%), Lushai (2.0%), Kom (2.0%) and Simte (1.5%). About 95% of the tribal population resides in rural areas, who predominantly practices agriculture. Agriculture is the main occupation of males, while the womenfolk are engaged in weaving and looming.

2.6 TRIBES OF TRIPURA

Tripura is one of the smallest states of India with a total population of 3,199,203. According to the 2001 Census report, the tribal communities comprise 31.1% of the total population. They come under 40 different ethnic communities The Tripuri are the main tribal group of the state and accounts for 54.7% of the total tribal population. Other tribal groups of Tripura include Reang (16.6%), Jamatia (7.5%), Chakma (6.5%), Halam (4.8%), Mag (3.1%), Munda (1.2%), Any Kuki Tribe (1.2%) and Garoo (1.1%). Tripura is a meeting point of both tribal and non-tribal culture, generating a unique combination of unusual cultures. Currently, Tripura is largely dominated by Bengali population, which constitutes the major portion of the population. The state is divided as North and South Tripura including hilly terrains and fertile land. These zones are home for tribal communities. The principal occupation of tribes of Tripura is agriculture, mainly in the form of Jhum cultivation. They live in elevated houses made of bamboo, known as the thong. Music and Dance are integral part of tribal culture of Tripura and each community is known for their specific forms of Dance and Music. Handicrafts and handloom practiced by the tribes of the state are famous and earned international recognition.

2.7 TRIBES OF MIZORAM

The Mizos belong to the mixed racial stock of Huns. They migrated from Chamdo region of Tibet to the Upper Burma and subsequently kept moving southwards and occupied what is now known as Patkai Hills and Hukwang Valley. The Mizo as an ethnic group assimilates many tribes, sub-tribes and clans. The transformation of diverse clans into a single common ethnicity was driven by common basic interest and also facilitated by adoption of Christianity, Roman Script and West Education. According to the Census of 2001, out of the total population of 888,573, the tribal communities comprises 94.5% of it. There are around 65 ethnic communities of which Lushai or Any Mizo Tribe is the largest group comprising of 77% of total tribal population. Other major tribal groups includes the Chakma (8.5%), Pawi (5.0%), Lakher (4.3%), Any Kuki Tribe (2.5%), Hmar (2.2%), Khasi (0.2%) and Any Naga Tribe (0.1%). Beside these, other smaller groups include Syntheng, Dimasa, Garo, Mikir, Man and Hajong. The broad groups of Mizo are classified into 15 different communities, which include Ngente, Khiangte, Chwangthu, Renthlei, Zowngte, Khwlhring, etc. These groups though have distinct identity, still they are no longer considered separate. Religious beliefs of all Mizos are strictly based in Christianity. Literacy rate is significantly high among the Mizos.

2.8 TRIBES OF MEGHALAYA

Meghalaya constitutes 85.9% tribal population mainly comprising of Khasis (56.4%) and Garos (34.6%). Out of the total population of 2,318,822, the tribal population comprises 1, 992,862 persons. The state has registered 31.3% decadal growth in Tribal population in the period 1991-2001. There are around 25 tribal communities of which Khasis constitute almost half of the total tribal population, followed by the Garos and both together comprise 91% of the total tribal population. In Meghalaya smaller tribal groups include the Hajong (1.6%), Raba (1.4%), Koch (1.1%), Synteng (0.9%), Mikir (0.6%), AnyKuki Tribe (0.5%), Lushai (0.2%), Naga (0.2%), Boro-Kacharis (0.1%) and Hmar (0.1%). The tribal population is pre-dominantly rural (97.2%), while only a small part of the population resides in urban areas. The state was carved out from Assam in 1973 and divided into seven administrative districts. Khasis are the group, who follows matrilineal social structure. They are Mon-Khmer speaking people mostly residing in East and West Khasi Hills and the Jaintia Hills. Garos are predominantly concentrated in the Garo Hills and preferred to be called the Mande or Achik (Ali and Das, 2003). The social structure of these tribes are predominantly matrilineal, which follows the matriarchal law of inheritance (Ali and Das, 2003). Females have the custody of property and holds key position in the family, which is passed onto the youngest daughter from mother. The Khasis and Jantias speak the language that belongs to the Mon-Khmer family of Austric connection, while the Garo language has proximity with Bodos belonging to Tibeto-Burmese family of languages (Ali and Das, 2003).

2.9 TRIBES OF ASSAM

The state of Assam comprises of 12.4% of tribal population, registering 15.1% decadal growth in population in 1991-2001. There are around 80 tribes that are distributed in different parts of the state. In addition to recorded major tribal population, good numbers of other tribal communities belonging to Naga, Mizo, Kuki, Chorei, Reang and Tripuri are also existent in Assam. Topographically, Assam is distinguished into three distinct zones viz., the Brahmaputra Valley in the North, Karbi-Anglong or Dima-Hasao comprising the central regions and Barak Valley in the south. About 95.3% of the tribal population of Assam are rural and practice agriculture and handicraft as their primary occupation. Bodos represent almost half of the total tribal population, followed by other tribes. The districtwise breakup of tribal population of Assam shows that more that 68% of the population in Dima-Hasao are tribal, which is followed by KarbiAnglong with ~55% tribal population. In Dhemaji and Kokrajhar districts the tribal population is 47.3% and 33.7%, respectively. The majority of the tribal communities in districts like Kamrup, Cachar, Karimganj, Hailakandhi and Dibrugarh are urban, while a small portion of them are located in rural areas.

2.10 TRIBES OF SIKKIM

Sikkim is one of the most beautiful States of North east India with an area of 7300 sq. km. The state is interlaced with jungle-clad ridges and deep ravines created by the Mountain Rivers, emerald valleys and dense forests. The original Lepcha inhabitants call Sikkim Myel Lyang “the land of hidden paradise”. To the Bhutias, it is Beyul Demojong the hidden valley of rice and the Limbus call it Sukhim, which means ‘the new house’. The landscape of this tiny State is dominated by the world’s highest mountain peaks like Kangchendzonga, the third highest mountain on earth. It has played a major unifying role among these three major ethnic communities of Sikkim. This mountain has been worshipped by the Lepchas from very early times. It is equally revered by the Bhutias and Nepalese. Pang Lhabsol is an annual festival celebrated. The population of Sikkim is about 5.5 lakhs, mainly consisting of the Nepalese, the Lepchas and the Bhutias. Of these, the Nepalese are the largest in number followed by the Bhutia and Lepcha communities. A small number of people from other parts of the country have also settled in Sikkim. Despite such an ethnic diversity, a remarkable feature of Sikkimese society is the tolerance and acceptance of different cultures and their harmonious co-existence. The Lepchas are the earliest settlers of Sikkim. Lepchas belong to one of the Naga tribes or are associated with the Jimdars and Mech in their eastward migration from Nepal. Some scholars have found a similarity between the Lepachas and the tribes in Arunachal Pradesh. Yet some others contend they are related to the Khasis in Meghalaya. The Lepchas themselves are convinced that their home has always been the legendary kingdom of Mayel in the vicinity of Mt. Kangchendzonga. The Lepchas have their own language and script. The Lepcha dances, songs and folk tales reflect a wonderful synthesis between men and nature. The Bhutias are mainly descendants of the early settlers in Sikkim from Tibet and Bhutan who accompanied the ancestors of the first Chogyal, Phuntsok Namgyal. Tibetan Buddhism played a special role in shaping the Bhutia society. Every household ritual, marriage, birth, death ceremonies and agricultural rites are conducted by the monks from the Gompas. Like the Lepchas and the Nepalese, the Bhutias are fond of their “chang”, the local brew. This preparation from fermented millet is served in bamboo containers. It has become an indispensable part of every Sikkimese ceremony, whether religious or secular. The Bhutias are famous for their weaving, woodcarving and the Thanka painting. Important festivals observed by the Bhutia community include Losoong, Pang Lhabsol, Kagyat dance and Saga Dawa. The Nepalese community of Sikkim is itself a conglomeration of diverse ethnic groups, some speaking their own vernacular. These ethnic groups can be roughly divided between the Magars, Murmis, Tamangs, Gurungs, Rais, Limbus, Damis, Kamis, Bahuns and the Chhetris. Most Nepalese are Hindus or Buddhists. Some of them have also adopted Christianity. The Rais, Limbus, Magars, Murmis, Tamangs and Gurungs have somewhat similar physical characteristics inasmuch as they are all Mongoloid. But each group has its own distinctive culture. The major festivals of the Hindu Nepalese in Sikkim are Dasain, Teohar, Makar Sankranti and Baisakhi.

2.11 CONCLUSION

Studies have shown that each of the tribal communities of North-East India differ in terms of their culture and tradition, which provides them a distinct identity. North-East India is a very important region of India with very rich cultural heritage. The region is very rich in ethnic diversity with varied origins. Several languages and dialects are spoken. As a part of their various culture and social behavior they have utilized the diverse flora (and fauna) for their day-to-day requirements and thus have contributed to a very rich traditional knowledge. With the increase in urbanization and eagerness to adopt modern ways of life, the traditions and culture are becoming extinct day-by-day. It is important to note that the impact of development in terms of improving the living standard has affected traditional culture significantly. Most of the ethnic population, particularly in state of Assam have preferred to adopt urban way of life. It is, therefore, imperative to emphasize that the conservation and preservation of ethnic culture and traditions vis-à-vis socio-economic development of the tribes requires important and pointing attention.

KEYWORDS

- Arunachal Pradesh

- Assam

- Culture

- Ethnic languages

- Manipur

- Meghalaya

- Mizoram

- Nagaland

- Origin of tribes

- Sikkim

- Society

- Tripura

REFERENCES

1. Ali, A. N. M. I., & Das, I. (2003). Tribal Situation in North East India. Stud. Tribes Tribals, 1 ( 2 ), 141–148.

2. Allchin, B., & Allchin, R. (1982). The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

3. Bhasin, M. K., Walter, H., & Dankor-Hopfe, H. (1994). An investigation of biological variability in Ecological Ethno-economic and Linguistic Groups. Kamla-Raj Enterprises, Delhi, India:

4. Bijukumar, U. (2013). Social exclusion and ethnicity in northeast India. NEHU Jour. 9 , 19–35.

5. Cavalli-Sforza, I., Menozzi, P., & Piazza, A. (1994). The History and Geography of Human Genes. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

6. Das, B. M. (1970). Anthropometry of the Tribal groups of Assam, India. Florida: Field Research Project.

7. Das, B. M., Walter, H., Gilbert, K., Lindenberg, P., Malhotra, K. C., Mukherjee, B. N., Deka, R., & Chakraborty, R. (1987). Genetic variation of five blood polymorphisms in ten populations of Assam India. Int. J. Anthrop, 2 , 325–340.

8. Dutta, B. K., & Dutta, P. K. (2005). Potential of ethnobotanical studies in North East India: An overview. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 4 , 7–14.

9. Gadgil, M., & Guha, R. (1992). The Fissured Land: AN Ecological History of India. Oxford Univ. Press, New Delhi, India.

10. Gadgil, M., Joshi, N. V., Prasad, U. V., Manoharan, S., & Patil, S. (1998). Peopling of India. (pp. 100–129). In: Balasubramanian, D., & Appaji Rao, N. (Eds.), The Indian Human Hertiage. Universties Press, Hyderabad, India

11. Kala, C. P. (2005). Ethnomedicinal botany of the Apatani in the Eastern Himalayan region of India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 1 , 11.

12. Kashyap, V. K., Sarkar, N., Sahoo, S., Sarkar, B.N. & Trivedi, R. (2003). Genetic variation at fifteen microsatellite loci in human populations of India. Curr Sci. 85 , 464–473.

13. Kumar, V., Basu, D., & Reddy, B. M. (2004). Genetic Heterogeneity in Northeastern India: Reflection of Tribe-Caste Continuum in the Genetic Structure. Amer. J. Human Biol. 16 , 334–345.

14. Misra, S. (1992). The age of the Achenlian in India: New evidence. Curr. Anthropol, 33 , 325–328.

15. Sankalia, H. D. (1974). Prehistory and protohistory of India and Pakistan. Deccan College, Poona, India.

16. Singh, K. S. (1998). People of India. Anthropological Survey of India and Oxford University Press, Delhi, India.

PLATE 1 : Map of North East India (Source: National Atlas and Thematic Mapping Organization, Govt. of India).