CHAPTER 6

ETHNOBOTANY OF OTHER USEFUL PLANTS IN NORTH-EAST INDIA: AN INDO-BURMA HOT SPOT REGION

CONTENTS

6.2 Bamboo: A Prominent Non-Timber Forest Product Linked With Ethnicity Of North East India

6.7 Insecticide/Insect Repellent

6.8 Ichthyotoxic And Fish Feed Plants

ABSTRACT

In the present chapter ethnobotany of other useful plants has been described which may be inextricably and intimately linked with rural livelihood of diverse tribes existing in North East India. Initially, in this chapter ethnobotany of Bamboos and Canes (Rattans) is described and overviewed. Further, ethnobotany of useful plants serving multifaceted purposes apart from ethnomedicine and food are described. These include dye-producing plants, fiber yielding plants and plants used for preparation of wine and pickles have been described. Use of under-utilized plants or less exploited plants to be used for diverse economic benefits for the livelihood improvement is intimately linked with socio-economy of North East India, an Indo Burma hot spot region.

6.1 INTRODUCTION

Biodiversity at local, regional and global level is intimately as well as inextricably linked with environment as well as economy. Plant diversity boosts the economy by providing food, fiber, timber and non-timber forest produce (NTFP), for example, botano-chemicals while it maintains a healthy environment by efficiently regulating the gaseous and nutrient cycling. Forest resources thriving immense biodiversity may be inextricably connected with socio-economic livelihood and hence Sustainable Development of North East India (NE, India) (Rai, 2015).

The Indian Subcontinent is one of the seventeen mega-biodiversity centers of the world particularly rich in plant resources linked with the human health and welfare (Rai and Lalramnghinglova, 2010a,b,c; 2011 a,b). North East India encompasses a significant portion of Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot (Myers et al., 2000; Rai, 2009).

The North East Region (NER) of India is perhaps one of the most vibrant and complex areas to administer, of the 600 odd ethnic communities that inhabit India, well over 200 ethnic groups are found in this region (Rocky, 2013).

World over, the tribal population still stores a vast knowledge on utilization of local plants as food and other specific uses (Sundriyal et al., 1998; Pfoze et al., 2014). In an ethnobotanical exploration of Nagaland

(Pfoze et al., 2014) a total of 628 number of species recorded in the study, 73.88% (464) of the species are used as ethnomedicine, 27.23% (171) as edible plants, 13.69% (86) as edible fruits, 5.73% (36) as dyes, 4.30% (27) as fish poison, 1.60% (10) as fermented food and beverage, 1.75% (11) as fodder and pasture grass and about 7.96% (50) for other uses such as fibers, furniture, jams and pickles, oil and gum, masticatory, plants use as seasonal indicator, etc. (Pfoze et al., 2014). Similarly, about 318 genera of ethnomedicinal plants, 124 genera of edible plants and 53 genera of edible fruits. Hazarika et al. (2015) investigated ethnobotany of other useful plants used for purposes other than ethnomedicine (See Tables 6.1–6.3). Devi (1980) has given the details of museological aspects of ethnic tribes of Manipur valley.

Albizzia odoratissima and Albizzia procera are the two main sources of fodder tree species in the Mizoram (Sahoo et al., 2010).

6.2 BAMBOO: A PROMINENT NON-TIMBER FOREST PRODUCT LINKED WITH ETHNICITY OF NORTH EAST INDIA

Bamboo is a predominant under-story species in forest ecosystems of NE India. Out of the 150 species of bamboo available in India, 58 species are present in NE India (Rai, 2009). Bamboo is an important commercial source for a variety of purposes, such as manufacture of paper, construction of houses, bridges, furniture, bags and baskets, and is also utilized, although to a limited extent, as fuel and fodder (Rai, 2009). Bhatt et al. (2003) also mentioned the various economic importance of bamboo in the form of food (young shoot), timber, and as agricultural implements (culms and branches) in three states (Mizoram, Meghalaya and Sikkim) of NE India. Bamboo is also inextricably linked with the traditional culture as well as ethnicity of peoples of NE states, and various festivals are based on it with the performance of bamboo dance (Rai, 2009). Therefore, in real sense, bamboo is poor man’s timber in NE states of India.

TABLE 6.1 Underutilized and Unexploited Fruits from Ethnobotanical Plants Used for Making Oil

| S. No. | Plant species | Part Used |

| 1 | Terminalia bellerica (Combretaceae) | Seed |

| 2 | Phoenix dactylifera (Arecaceae) | Seed |

| 3 | Emblica officinalis (Euphorbiaceae) | Fruit |

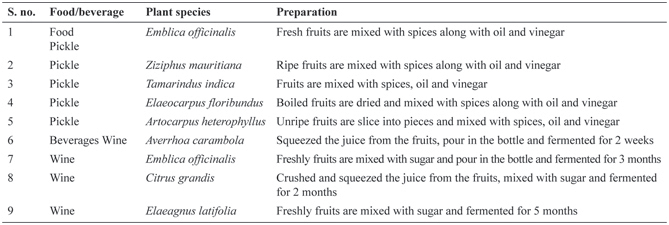

TABLE 6.2 Ethiiobotanical Plants Used to Prepare Pickle and Wine of Commercial Importance

(Reprinted from Hazarika, T. K., Marak, S., Mandai, D., Upadhyay, K., Nautiyal, B. P, & Shukla, A. O. (2015). Underutilized and unexploited fruits of Indo-Bunna hot spot, Meghalaya, north-east India: etlmo-medicinal evaluation, socio-economic importance and conservation strategies. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 63(2), 289-304. With permission of Springer.) Ethnobotany of India, Volume 3

TABLE 6.3 Other Ethnobotanical Plants of Miscellaneous Use

| S. No. | Plant species | Family | Uses |

| 1. | Dillenia pentagyna | Dilleniaceae | Leaves for packing material |

| 2. | Sterculia villosa | Malvaceae | Bark for making ropes |

| 3. | Artocarpus heterophyllus | Moraceae | Wood for making furniture |

| 4. | Ficus glomerata | Moraceae | Wood containers |

| 5. | Ficus lamponga | Moraceae | Wood containers |

Bamboo shows a characteristic simultaneous mass flowering after long intervals of several decades. Bamboo species flower suddenly and simultaneously then all the flower clumps die, leading to drastic changes in forest dynamics and environmental conditions, for example, light intensity, seedling survival, organic matter decomposition, and nutrient cycling, although complete destruction of bamboo clumps requires another few years. Bamboo communities follow active nutrient cycling and their vigorous growth and litter production ameliorates nutrient impoverished coal mine spoil and tropical soil fertility (Rao and Ramakrishnan, 1989; Singh and Singh, 1999; Mailly et al., 2007; Takahashi et al., 2007; Rai, 2009). However, after mass flowering and death, nutrient uptake by the bamboo ceases and large amounts of dead organic matter are deposited (Rai, 2012).

Ethnopedology is the documentation and understanding of local approaches to soil perception, classification, appraisal, use and management (WinklerPrins and Sandor, 2003; Nath et al., 2015). It is widely recognized that farmers’ hold important knowledge of folk soil classification for agricultural land for its uses, yet little has been studied for traditional agroforestry systems (Nath et al., 2015). Nath et al. (2015) explored the ethnopedology of bamboo (Bambusa sp.) based agroforestry system in North East India, and establishes the relationship of soil quality index (SQI) with bamboo productivity.

6.3 RATTANS (CANE)

The name ‘cane’ (rattan) stands collectively for the climbing members of a big group of palms known as Lepidocaryoideae. Rattans/canes are prickly climbing palms with solid stems, belonging to the family Arecaceae and the sub-family Calamoideae. They are scaly-fruited palms. The rattans/ canes comprise more than fifty per cent of the total palm taxa found in India (Basu, 1985; Lalnuntluanga et al., 2010). Rattan forms one of the major biotic components in tropical and sub-tropical forest ecosystem (Lalnuntluanga et al., 2010). The flora of Assam is still regarded as a major floristic account ofthe North East region (Kanjilal et al., 1940; Lalnuntluanga et al., 2010). Anderson (1871) enumerated 7 species of rattans of Sikkim (viz., Calamus erectus, C. flagellum, C. leptospadix, C. tenuis, C. acanthospathus, C. guruba and C. latifolius). In-depth studies on rattans have been started recently in the region. Thomas and Haridasan (1999) reported 24 species of rattans under 4 genera (Calamus, Daemonorops, Plectocomia and Zalacca) from Arunachal Pradesh (Lalnuntluanga et al., 2010). Singh et al. (2004) reported 13 species, viz., C. acanthospathus, C. arborescens, C. collina, C. erectus, C. flagellum, C. floribundus, C. guruba, C. inermis, C. latifolius, C. leptospadix, C. tenuis, Daemonorops jenkinsianus and Plectocomia bractealis, under 3 genera (Calamus, Daemonorops and Plectocomia) from Manipur. Deb (1983) reported 6 species, viz., C. viminalis, C. floribundus, C. tenuis, C. leptospadix, C. guruba and C. erectus, belonging to the genus Calamus from Tripura. Haridasan et al. (2000) reported the presence of 3 species of Calamus (viz., C. leptospadix, C. tenuis and C. erectus) from Meghalaya, 1 species of Daemonorops (viz., D. jenkinsianus) from Nagaland and 6 species of Calamus (viz., C. leptospadix, C. inermis, C. latifolius, C. flagellum, C. erectus and C. acanthospathus); 1 species each of Daemonorops (viz., D. jenkinsianus) and Plectocomia (viz., P himalayana) from Sikkim (Lalnuntluanga et al., 2010).

6.4 DYE YIELDING PLANTS

Borthakur (1981), Akimpou et al. (2005), Singh et al. (2009), Teron and Borthakur (2012), Pfoze et al. (2014), and Hazarika et al. (2015) gave an account of dye yielding plants and dyeing system of Manipur and North-East India, details of which are given below.

- Bixa orellana L.: The plant imparts reddish color to clothes or yarn threads. Seeds are taken in clean and thin clothes and rubbed into the water with hand. The liquid thus obtained is used for dyeing clothes or yarn threads

- Carthamus tinctorius L.: The petals yield a pink dye. The petals are collected and kept until they become decayed. The decayed petals are rolled in the palm making into balls of thumb size. Two or three balls are enough to dye the yarn threads for one phanek (skirt).

- Clerodendron odoratum D. Don: This dye gives pale green color to the clothes. Leaves are collected and crushed into the tub containing water. The water turns light green in color. Then the thread or cloth is soaked overnight and slightly squeezed and spread in shade. The process is repeated 6 to 7 times until the desired color is obtained.

- Croton caudatus Gelseler: Sap of twigs is used for black dye of crafts.

- Curcuma domestica Valenton (Syn.: C. longa L.): The plant gives yellowish color. Fresh rhizomes are crushed into pieces and allowed to soak in water. Clothes or threads are soaked overnight and dried.

- Garcinia xanthochymus Hook.f. & T. Anderson Yellow, pale rose and maroon red dye is extracted from the plant used for dyeing the garments.

- Indigofera tinctoria L. Leaves and flower buds are used to extract indigo/blue dye for dyeing garments.

- Justicia comata (L.) Lam. Leaves and shoots used to extract pink dye used for crafts.

- Machilus gamblei King ex Hook.f. Bark is used to extract red dye used for garments.

- Marsdenia tinctoria R. Br. Leaves are used to extract indigo/blue dye used for tattoos.

- Morinda angustifolia Roxb. Roots are used to extract yellow dye used for dyeing garments.

- Pasania pachyphylla (Kurz) Schottky: Stem bark is cut into pieces and soaked in a pitcher containing water for 6 to 7 days. It is used to obtain black color and dark brown color. For pure black, the thread or cloth is alternately soaked in Strobilanthes cusia (Nees) Imlay liquid and Pasania pachyphylla liquid until the desired color is obtained. And for dark brown color it is soaked in Quercus spp. prepared liquid.

- Plumbago indica L.: Flowers are collected in large amount and its petals are crushed and soaked in water. Clothes or yarn threads dipped into the liquid acquire red color.

- Quercus dealbata Hook.f. & Thoms. The plant gives dark brown color (of less color intensity) to the clothes/yarn threads. The bark is cut into pieces and soaked in a pitcher containing water.

- Shorea robusta Gaertn. Red dye is extracted from tender leaves for dyeing crafts.

- Strobilanthes cusia (Nees) Imlay: Mature leaves are collected and soaked in a pitcher containing water. The pitcher is kept undisturbed until the leaves are completely decayed. The pitcher is stirred with a multipronged stick. Solid things are removed while stirring. Ashes taken from burning oyster is added and stirred continuously. Now liquid is ready for dyeing clothes. It is mainly used to dye black color.

- Strobilanthes flaccidifolia Nees Kum dye is prepared from the plant.

- Tectona grandis L.f.: Leaves or barks are cut into pieces and soaked for 2-3 days in water. Clothes or yarn threads which are dipped into this dye give somewhat reddish color.

- Terminali bellirica (Gaertn.) Roxb. Black dye is extracted from fruits for dyeing cordage.

6.5 WOOD CRAFTS

The close and even grained wood of many Rhododendron species such as R. arboreum, R. hodgsonii, R. falconeri, etc. are used for the ‘Khukri’ handles, pack-saddle, cups, spoons, ladles, gift boxes, gun-stocks, and posts by Bhutias, Lepchas and Nepalese.

The yak pastoralists, known as Brokpas, of Arunachal Pradesh are expert craftsmen making all the items of their daily utility for processing and storing yak products by themselves. The wood of Quercus wallichiana and Bamboo species, Dendrocalamus hamiltonii, Bambusa tulda and B. pallida are used for these purposes (Bora et al., 2013).

The wood of Hibiscus tiliaceus is used by the Great Andamanese to make buoys (phota) for fishnets. Bark from the trunk is removed, sun dried, and scraped to extract fibers used to weave items such as harpoon lines and nets; the fiber is also used to make bracelet.

6.6 INCENSE

The leaves of Rhododendron anthopogon are mixed with those of junipers to provide incense that is widely used in Buddhist monasteries in Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh.

6.7 INSECTICIDE/INSECT REPELLENT

It is reported that the vegetative parts of Rhododendron thomsonii is boiled and the highly poisonous extract is used as natural insecticide in Lachen and Lachung villages of north-east Sikkim (Pradhan and Lachungpa, 1990). Similarly the leaves extract of Rhododendron dalhousiae var. rhabdotu is used as insect repellent by the Monpas of Arunachal Pradesh (Paul et al., 2010).

6.8 ICHTHYOTOXIC AND FISH FEED PLANTS

Community seasonal fishing and hunting are of great economic activities of many tribal people including Monpa ethnic group in addition to agriculture. Chetri et al. (1992) also gave an account of ethnobotany of ichthyotoxic plants in Meghalaya. Tag et al. (2005) reported that the following plants are used as fish poison by the hill Miri tribe of Arunachal Pradesh: Aesculus pavia (bark, leaves), Cyclosorus extensus (whole plant), Acacia pennata (whole plant), Ageratum conyzoides (whole plant), Anamirta cocculus (fruits), Croton tiglium (bark, leaves), Gynocardia odorata (pulp of fruits), Polygonum hydropiper (whole plant), Spiranthes oleracea (whole plant), Tephrosia candida (leaves, seeds) and Zanthoxylum nitidum (bark, fruits). Namsa et al. (2011) documented the use of the following plants for stupefying and poisoning the fish. The study revealed a wealth of indigenous knowledge and procedures related to poison fishing with the aid of poisonous plants. This easy and simple method of fishing are forbidden in urban areas but still practiced in remote tribal areas. The active ingredients were released by macerating the appropriated plant parts with the help of wooden stick or hammer, which were then introduced into the water environment. Depending upon time and conditions, the fish begin to float to the surface where they can easily be collected with bare hand. A total of seven plant species, namely Castanopsis indica, Derris scandens, Aesculus assamica, Polygonum hydropiper, Spilanthes acmella, Ageratum conyzoides, and Cyclosorus extensus were used to poison fish during the month of June-July every year and leaves of three species like Ipomoea batatas, Mannihot esculenta, and Zea mays were used as common fish foodstuffs. The two main molecular groups of fish poisons in plants (the rotenones and the saponins) as well as a third group of plants which liberate cyanide in the water account for nearly all varieties of fish poisons. The underground tuber of Aconitum ferrox was widely used in arrow poisoning to kill ferocious animals like bear, wild pigs, gaur and deer. The killing of Himalayan bear was very common practice among the tribal people and the gall bladders are highly priced in the local market. The dried gall bladders of bear are given orally in low doses to cure malaria since ancestral times. Fresh bark of Aesculus assamica Griffith collected and pounded with wooden stick used as fish poison. Juice and paste of Ageratum conyzoides L. used as fish poison. Whole plant extract of Castanopsis indica Roxb. is used to poison fish. Derris scandens (Roxb.) Benth. roots are pounded with wooden stick and thrown into the river to poison fishes. Polygonum hydropiper L. whole plant extract is used to poison fish. Paste or boiled leaves and young twigs of Spilanthes oleracea Murr, are used as fish poison.

6.9 CONCLUSION

The present review emphasizes the use of under-utilized plants or less exploited plants to be used for diverse economic benefits for the livelihood improvement intimately linked with socio-economy of North-East India, an Indo Burma hot spot region. The development of traditional knowledge to suit new lifestyle would result huge benefit upon livings. The global consumers were aware on the benefits of the natural products.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author is thankful to Professor Amar Nath Rai, Former Director, NAAC, Vice chancellor Mizoram and North Eastern Hill University, India. The author is further thankful to Prof. Lalramghinghlova, Prof. Lanuntluanga, Prof. U. K. Sahoo and Dr. T. K. Hazarika for their kind cooperation and literature provided.

KEYWORDS

- bamboo

- beverages

- canes

- dye yielding plants

- livelihood

REFERENCES

1. Akimpou, G., Rongmei, K., & Yadava, P. S. (2005). Traditional dye yielding plants of Manipur. Northeast India. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 4 (1), 33–38.

2. Anderson, T. (1871). An enumeration of the palms of Sikkim. J Linn Soc (Botany) , 11 , 4–14.

3. Basu, S. K. (1985). The present status of Rattans Palms in India: An overview. In ProceedingsRattan (Ed.), Wong & Manokaran (pp. 77–94). Kuala Lumpur: Seminar.

4. Bhatt, B. P., Singha, L. B., Singh, K., & Sachan, M. S. (2003). Commercial edible bamboo species and their market potential in three Indian tribal states of North Eastern Himalayan Region. J. Bamboo and Rattan , 2 (2), 111–133.

5. Bora, L., Paul, V., Bam, J., Saikia, A., & Hazarika, D. (2013). Handicraft skills of Yak pastoralists in Arunachal Pradesh. Indian J. Trad. Knnowl. , 12 (4), 718–724.

6. Borthakur, S. K. (1981). Studies on ethnobotany of Karbis (Mikirs): Plants mastigatories and dyestuffs. In S. K.Jain (Ed.), Glimpses of Indian Ethnobotany (pp. 180–190). Jodhpur: Scientific.

7. Chetri, R. B., Kataki, S. K., & Boissya, C. L. (1992). Ethnobotany of some ichthyotoxic plants in Meghalayas, North-eastern India. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. Addl. Ser , 10 , 285–288.

8. Devi, D. L. (1980). Ethnobiological studies of Manipiur valley with reference to Museological aspects. PhD thesis, Manipur university.

9. Deb, D. B. (1983). The Flora of Tripura State, Volume-II. Today & Tomorrow’s Printers and Publishers ,428–430.

10. Haridasan, K., Thomas, S., & Sharma, A. (2000). Bamboo and rattan (cane) in North-East India with special reference to Arunachal Pradesh. In:S. C.Tiwari & P PDabral, eds. International Book Distributor, 9/3 Rajpur Road, Dehra Dun, pp. 39-58.

11. Hazarika, T. K., Marak, S., Mandal, D., Upadhyay, K., Nautiyal, B. P., & Shukla, A. O. (2015). Underutilized and unexploited fruits of Indo-Burma hot spot, Meghalaya, north-east India: ethno-medicinal evaluation, socio-economic importance and conservation strategies. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. , 63 (2), 289–304.

12. Kanjilal, U. N., Kanjilal, P. C., Das, A., De, R. N., & Bor, N. L. (1940). Flora of Assam. Vols. 1-5. Shillong.

13. Mailly, D., Christanty, L., & Kinunins, J. P. (1997). ‘Without bamboo, the land dies’: nutrient cycling and biogeochemistry of a Javanese bamboo tahn-kebun system. ForestEcol Manage , 91 , 155–173.

14. Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B., & Kent, J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature , 203 , 853–858.

15. Namsa, N. D., Mandal, M., Tangjang, S., & Mandal, S. C. (2011). Ethnobotany of the Monpa ethnic group at Arunachal Pradesh. India: J Ethnobiol Ethnomed.

16. Nath, A. J., Lal, R., & Das, A. K. (2015). Ethnopedology and soil quality of bamboo (Bambusa sp.) based agroforestry system. Science of the Total Environment , 521–522 , 372–379.

17. Paul, A., Khan, M. L., & Das, A. K. (2010). Utilization of Rhododendrons by Monpas in Western Arunachal Pradesh. India. J. Amer. Rhododendron Soc. ,81–84.

18. Pfoze, N. L., Kehie, M., Kayang, H., Mao, A., & A., (2014). Estimation of Ethnobotanical Plants of the Naga of North East India. J. Medicinal Plants Studies. , 2 (3), 92–104.

19. Pradhan, U. C. & Lachungpa, S. T. (1990). Sikkim-Himalayan Rhododendrons. Kalingpong: Primulaceae books.

20. Rai, P. K. (2009). Comparative Assessment of soil properties after Bamboo flowering and death in a Tropical forest of Indo-Burma Hot spot. Ambio , 38 (2), 118–120.

21. Rai, P. K. (2015). Environmental Issues and Sustainable Development of North East India. Germany: Lambert Publisher.

22. Rao, K. S. & Ramakrishnan, P. S. (1989). Role of bamboos in nutrient conservation during secondary succession following slash and burn agriculture (jhum) in north-east India. J Appl Ecol , 26 , 625–633.

23. Rocky, R. L. (2013). Tribes and Tribal Studies in North East: Deconstructing the Philosophy of Colonial Methodology. J. Tribal Intellectual Collective India. , 1 (2), 25–37.

24. Sahoo, U. K., Lalremruata, J., Jeeceelee, L., Lalremruati, J. H., Lalliankhuma, C., & Lalramnghinglova, H. (2010). Utilization of Non timber forest products by the tribal around Dampa tiger reserve in Mizoram. The Bioscan , 3 , 721–729.

25. Singh, A. N. & Singh, J. S. (1999). Biomass, net primary production and impact of bamboo plantation on soil redevelopment in a dry tropical region. For Ecol Manage , 119 , 195–207.

26. Singh, H. B., Puni, L., Jain, A., Singh, R. S., & Rao, P. G. (2004). Status, utility, threats and conservation options for rattan resources in Manipur. CurrentSci. , 87 (1), 90–94.

27. Singh, N. R., Yaipabha, N., David, T., Babita, R. K., Devi, C. B., & Singh, N. R. (2009). Traditional knowledge and natural dyeing system of Manipur with special reference to Kum dye. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. , 8 (1), 84–88.

28. Sundriyal, M., Sundriyal, R. C., Sharma, E., & Purohit, A. N. (1998). Wild edible and other usefulplants from the Sikkim Himalaya, India. OecologiaMontana , 7 , 43–54.

29. Tag, H., Das, A. K., & Kalita, P. (2005). Plants used by the Hill Miri tribe of Arunachal Pradesh in ethnofisheries. Indian J. Trad. Knowl , 4 , 57–64.

30. Takahashi, M., Furusawa, H., Limtong, P., Sunanthapongsuk, V., Marod, D., & Panuthai, S. (2007). Soil nutrient status after bamboo flowering and death in a seasonal tropical forest in western Thailand. Ecol Res , 22 , 160–164.

31. Teron, R. & Borthakur, S. K. (2010). Traditional knowledge of herbal dyes and cultural significance of colors among the Krbis ethnic tribe in Northeast India. Ethnobotany Research & Applications , 10 , 593–603.

32. Thomas, S. & Haridasan, K. (1999). Rattans the prickly palms. Arunachal Forest News , 17 , 26–28.

33. WinklerPrins, A. & Sandor, J. A. (2003). Local soil knowledge: insights, applications, and challenges. Geoderma , 111 , 165–170.