CHAPTER 8

ETHNOBOTANY OF ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS

CONTENTS

8.1 The Andamans: People and their Culture

8.2 Tribal Diversity in Andamans (7.5%)

8.3 Ethnomedical Plants of Andamans

8.5 Ethnic Food Plants and Ethnic Foods of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands

ABSTRACT

The Andaman archipelago comprises of about 570 islands and encompasses an area of about 6,340 square miles. This chapter detail the ethnic tribes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands which include Great Andamanese, Onges, Jarawas, Sentinelese, Nicobarese and Shompen. The usage of plants for food, medicine and other uses by these ethnic people is given. In the Andamans studies on ethnic foods revealed minimal processing and no great efforts are devoted for preparing the foods. Plants foods of the Jarawas and Sentineleses are trivial and only few plants are consumed by them, the preparation methods are not known/not documented which suggest most foods are eaten raw. More ethnobotanical exploration is needed to analyze and document the ethnic foods consumed by tribal communities of the Andamans.

8.1 THE ANDAMANS: PEOPLE AND THEIR CULTURE

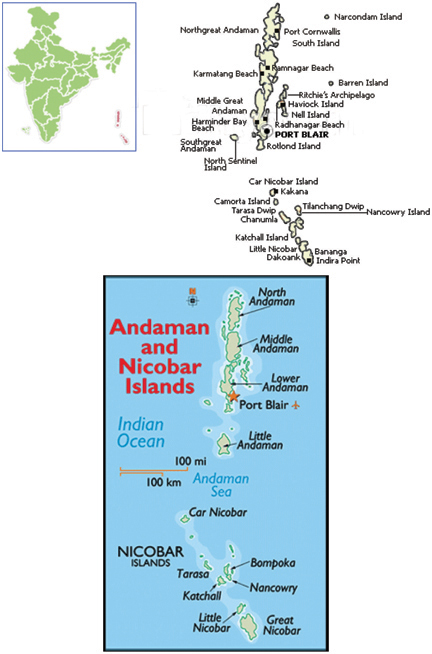

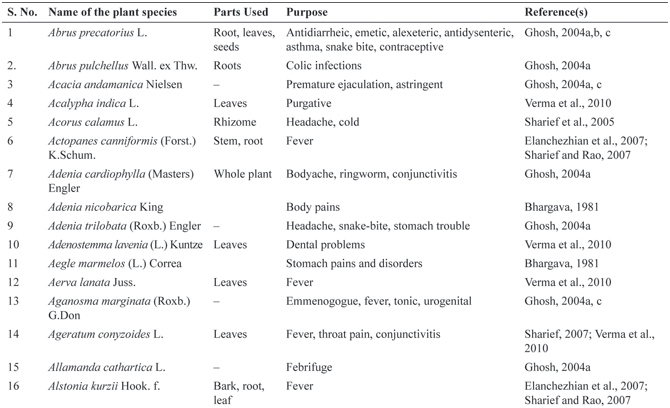

The Andaman archipelago comprises of about 570 islands and encompasses an area of about 6,340 square miles (Krishnakumar, 2009), situated in a north-south direction between 6° and 14° North and 92° and 94° East at the mouth of the Bay of Bengal (Awasthi, 1991). The Andamans are divided into two main groups of islands, Great Andaman and Little Andaman, separated by the Duncan passage (Figure 8.1). The Great Andaman is further subdivided into three separate groups: North Andaman, Middle Andaman, and South Andaman (Sekhsaria and Pandya, 2010). The entire land surface of the Andamans is hilly, enclosing narrow valleys; the tendency of slope is from east to west. The islands have typical tropical maritime climatic situation with average annual rainfall of 3100 mm, temperature ranges from 20 to 32°C and high relative humidity (70-92%). These islands are rich in floral biodiversity which represents elements of both North-East India and Indonesia-Myanmar regions (Balakrishnan and Ellis, 1996).

FIGURE 8.1 Map of the Andamans.

The Andaman Islands is home to indigenous tribes who are divided by two categories: the indigenous tribal people and the outsiders. Latter who are settled in the territory due to the fact of colonial rule, include Bengali, Tamil, Malayali, Telugu, Oriya, North Indian and others (Majumdar, 1975). The blend of these two classes of people constitutes a colorful ethnicity to the people’s profile of Andamans. The indigenous tribes are generally dark in color, short in stature with peppercorn hairs belonging to Negrito stock and represented by the Great Andamanese, the Onges, the Jarawas and the Sentinelese (Sharief, 2007). The aboriginal population of the Andaman Islands, along with the Semangs of Malaysia, the Aetas of the Philippines, and the few population groups of Papua New Guinea who morphologically resemble the African pygmies, are the remnants of the ‘Negrito’ populations of Southeast Asia (Kashyap et al., 2003). Formerly, the Onge tribe was semi-nomadic, roaming around the shores of the island in response to different seasons (Bhargava, 1983).

The aboriginal tribes of Andaman are known for their skills in arts and crafts. They excel in crafts related to shells, wood, cane and bamboo. Apart from this, mat making and basketry form an integral part of their culture. There is no specific attire which is used by the people of the Andamans and they still move around naked living in the inaccessible coastal areas. A slight refinement comes with the Jarawas where they use only adornments of bark and shell, like necklaces, armbands, waist bands, etc. But, however, all the ceremonial occasions are adorned by necklaces made of shell, waistbands and headbands of bark fiber. Thus, they still preserve their tradition and culture along with their language and religion. The main occupation of the people of these islands includes agriculture, forestry and fishing. Agricultural crops consist of rice, coconuts, betel (areca nuts), fruits and spices (turmeric), rubber, oil palms and cashews. During the khariff season, paddy becomes the prime field crop. Fishery is also another major occupation of the area and not meant for domestic use. Aboriginal tribes living in coastal forests mostly make best use of their surrounding forest produce for their daily needs, for example, fuel, fodder, edibles and others items but also come out of the forest towards sea coasts and utilize its resources too, to meet their basic requirements. Among other tangible culture of the Andaman, food system of the aboriginal tribes adds to the ethnic and cultural heritage of the region. Over the years, the interactions of native food systems and that of the migrants favored amalgamation and evolution of diverse food cultures which helped in identification of more new local food resources in this small archipelago (Singh et al., 2013). Dagar and Dagar (1999) gave a detailed account of plants and animals used by the Negrito and Mongoloid tribals of Andaman and Nicobar Islands in their routine life for food, shelter, dugout canoe making, taboos, rituals and medicines (Figure 8.1).

8.2 TRIBAL DIVERSITY IN ANDAMANS (7.5%)

8.2.1 GREAT ANDAMANESE

A small group of about 100 persons inhabiting little Andaman Islands. The Great Andamanese are traditionally non-vegetarian. Their staple food consists of fish, pig, crab, dugong, shellfish, turtle egg, and tubers, etc. The people are finely skilled in arts and crafts and therefore, are able to utilize several plant materials for their hunting tools. The Great Andamanese produce their string (bole) from the bark fiber of the climber Anodendron paniculatum. The fiber is also used to make string for harpoon lines, bowstrings, and turtle nets. Stem pieces of 1/2 or 1 m are taken by the Great Andamanese during fishing traps which is claimed that the obnoxious odor of the wood wards off attacks of large fishes and crocodiles. The eggs of birds are also collected for consumption. Besides that, various plants and plant products are gathered and consumed either in raw form or cooked as vegetable. Twenty-four plants have been reported to be used by the Andamanese as source of food. They are fond of seeds of Entada scandens, E. pursaetha, pith of Caryotas obolifera, two species of Dioscorea (yam) (Patnaik, 2006). Certain edible fruits of Terminalia catappa, Carica papaya, Annona squamosa, Acacia pennata, Artocarpus omeziana, Artocarpus integrifolia, Ficus nervosa, Moringa pterygosperma, Psidium guajava, Bruguiera gymnorrhiza, Calamus viminalis, Cocos nucífera, Pandanus andamanensium, Musa sapientum var. simiarum, Nypa fruticans, Manilkara littoralis, Citrus medica, Atalantia monophylla, Mangifera comptospermum, Mangifera indica, etc. are often consumed by the Great Andamanese (Awasthi, 1991). The people are expert in honey hunting and they employ various plant materials during the hunt. Paste, juice, and vapors of Polyalthia jenkinsii, obtained by chewing the leaves and sprayed by mouth on honeybees, are used to disperse these insects during honey collection. When the Great Andamanese raid a hive, they strip off the leaves and chew the stem; the liquid thus extracted is smear over their body. The same juice is used also to disperse the attacking bees. Bees are at once repelled by the obnoxious odor of the juice emitted in a fine spray from the mouth. Sometimes they use the chewed stalks to drive off the last defenders of the hive.

8.2.2 ONGES

Onges are pure hunter-gatherers and as they were formerly semi-nomadic, they never took any interest in cultivation. Of course, they do not destroy edible plants; on the contrary, they try to protect useful plants. They take only the required number of edible plants while the remaining is left for regeneration. This shows their natural interest in the conservation of the flora. The Onges eat mostly natural food in which the island abounds. They are very fond of jackfruit, yams, Pandanus species. The leaves of Pandanus sometime provide roofing for Onge shelters. They particularly like pilchards. They catch mollusks, Crustacea, lobsters, crayfish and crabs, even some kind of hermit crab. They eat cicada too. They collect the pupae which are supposed to be a great threat. It is noteworthy to mention that in the indigenous diet items of the Onge menu birds, crocodiles, lizards, jungle cats, bats, rats and snakes are not included because as per Onge beliefs they harbor spirit of dead or malevolent spirits. Onge tribals can consume even slightly toxic fruits or seeds, viz., Abrus precatorius, Barringtonia asiatica, Cycas rumphii and Dioscorea glabra after mild processing through boiling or roasting. Probably by heating the plant parts, the toxic properties are destroyed (Tanaka, 1976) which makes them less harmful to be consumed. The three food plants of the Onge tribe, viz, Cycas rumphii, Dioscorea glabra, and Pandanus are also used by the natives of southeastern Asian countries (Bhargava, 1983). Moreover, the procedures employed in cooking and consuming are similar to those of other Asian tribes (Anonymous, 1948-1972; Burkill, 1951; Smitinand, 1972; Tanaka, 1976; Bhargava, 1983). At present, the tribals are rapidly developing a taste for the well-cooked food of the civilized world. Wheat flour, rice, and fruits of Cocos nucífera have recently been added to their diet.

8.2.3 JARAWAS

Jarawas, also known as Ang, are considered to be the original inhabitants of the Andaman with the other Negrito tribes (Sarkar, 2008). They entirely depend on forest and marine sources for survival. Diet of the Jarawa includes varieties of fruits, tubers, honey, mollusk, fish, and animals like pig, wild boars, monitor lizard and turtle. Besides, honey was an important item of food for the Jarawas. Normally, men hunt crabs by hitting arrows when these were encountered in water or mudflats. The women use net for trapping the crabs and often dug out the crabs from burrows. The women and children usually caught fishes from shallow waters, in streams and near shoreline, by hand-nets. Jarawa women collected turtles’ eggs from the sandy beach in a bay area. The turtle nesting grounds were detected near the edge of tidal flat (high water mark), where grass grew. The women and children used to collect marine mollusks like trochus, turbo, giant clams, cowries, etc., from the inter-tidal areas of coral beds on open seashore or mouth of bay area. All kinds of fruits are eaten fresh, and a great portion is consumed on the gathering spot itself, except Pometía pínnata, Baucaría sapída, and Cycas, which are gathered in large quantities and carried to the camp. Men, especially the young ones, climb high up the trees to collect jackfruit, which becomes abundant during the peak dry season of the year. During this period jackfruit comprised a considerably high portion of their food, more at camps in interior parts of forest and less in coastal areas. Traditionally, food was cooked in pit ovens called aalaav; those were made inside or outside their huts for roasting food. Such ovens are mostly used to cook pig meat and jackfruit. After three to four hours the cooked food is taken out for consumption. In recent times, it has been observed that most of the time they boil pig meat and other items of food. Boiling is done in buchu or aluminum vessels either supplied by the AAJVS (Andaman Aadmi Janjati Vikas Samiti) or procured from the villages. The males process pig meat; cooking the meat in pit ovens is also done by them, while boiling meat in a buchu is not a gender specific job.

It has generally been observed that the males consume larger part of pig meat. If it is monitor lizard, only the males consume it without giving any share to the females.

The Jarawas are more dependent on animal foods for protein and fat. This is supplemented by a wide variety of plant foods that provide reasonable quantity of carbohydrates and vitamins. The Jarawas more often consume fruits and honey found in the forests rather than digging for tubers and roots (see Table 8.2). The Jarawas use fruits, nuts, seeds, leaves, tubers and roots of different plants as secondary source of diet. They eat many kinds of seeds and tubers, some are eaten raw and some are processed before eating. Most of these seeds and tubers are gathered and transported to the camp by women, while men and children occasionally help them when the seeds are abundant. Members of Botanical Survey of India collected information about 58 plants which provide food to the Jarawas. Frequently used ones are Artabotrys speciosus, A. chaplasha, A. lakoocha, Baccaurea ramiflora, Alamus andamanicus, Cycas rumphii, Dioscorea bulbifera, D. vexans, D. glabra, Diospyros andamanica, Ficus racemosa, Garcinia cowa, Mangifera andamanica, Pinanga manii, Donax canaeformis, Pometia pinnata and Terminalia catappa.

8.2.4 SENTINELESE

Sentinelese is a small tribal group of about 100 people of Negrito race inhabiting North Sentinel. The Sentinelese culture is based on observations during contact attempts in the late 20th century. They are noted for resisting attempts at contact by outsiders and their hostile attitude towards the strangers. Unlike the Andamanese, Onge and Jarawa, the Sentinelese have refused to have contact with outsiders, and seemingly as a result remain culturally intact and healthy. Repeated attempts by the administration to make friendly overtures to them have resulted only in arrows fired from trees or beaches on the island’s periphery. Their language remains unclassified. The Sentinelese maintain an essentially hunter-gatherer society, obtaining their subsistence through hunting, fishing, and collecting wild plants; there is no evidence of any agricultural practices or producing fire (Raghunathan, 1976). Food consists primarily of plant stuffs gathered in the forest, coconuts, which are frequently found on the beaches as flotsam, pigs, and, presumably, other wildlife (which apart from sea turtles is limited to some smaller birds and invertebrates). Fruits of Pandanus and Sapodilla remain their staple food. Wild honey is also seen to be widely collected by the Sentinelese.

8.2.5 NICOBARESE

Nicobarese is a tribe group of about 22,000 people. It is a Mangoloid race inhabiting Nicobarese group of islands in Bay of Bengal. Linguistically of non-Khmer branch of Austro-Asiatic family.

8.2.6 SHOMPEN

Shompen is a small tribal group of223 persons of Mongoloid race inhabiting the Great Nicobar Island in Bay of Bengal. Shompens are the aboriginal inhabitants of Great Nicobar Island. They probably migrated into this area, several hundred years ago from Malaysian regions and got admixtured with Nicobarese tribes at later stages. They are one of the Mongoloid aborigines. They are semi-nomadic, food gatherers and hunters with stone age civilization; live in small groups in dense interior forests of the island and exclusively depend on forest resources and sea products for most of their sustenance. The Shompens build temporary huts propped on stilts 2-6 m above ground. Inside the huts, crude mats made from pandanus and cane strips are used and leaves of Leea grandiflora Kurz. serves bed sheets, while a piece of bamboo is often used as pillow. The Shompens prepare indigenous dugouts or canoes called ‘horis,’ which are of two types. Small canoes having carrying capacity of two or three persons are used for crossing creeks and rivers. Big canoes having carrying capacity of 2-7 persons are used for transportation and fishing in the sea. These canoes which vary in size from 6 to 10 ft., are generally fixed with outrigger for balance and moved using paddles.

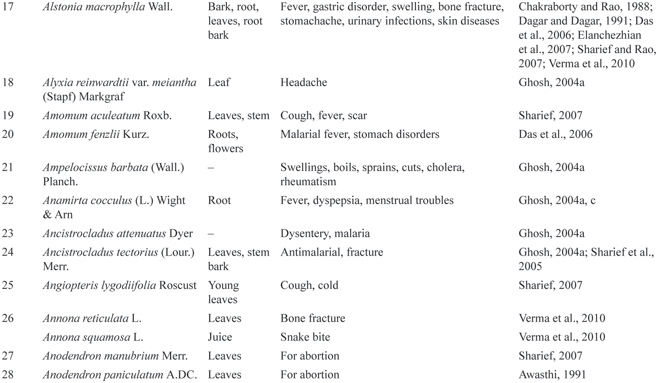

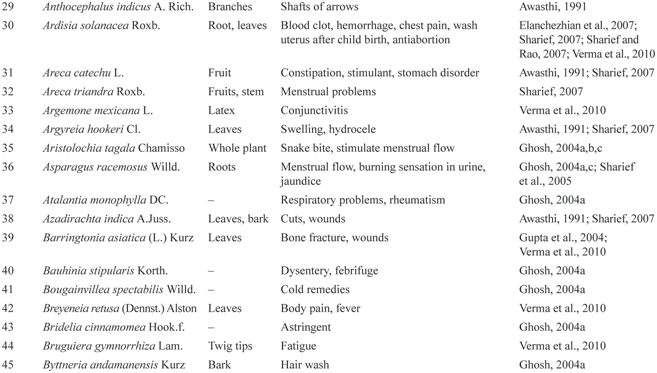

8.3 ETHNOMEDICAL PLANTS OF ANDAMANS

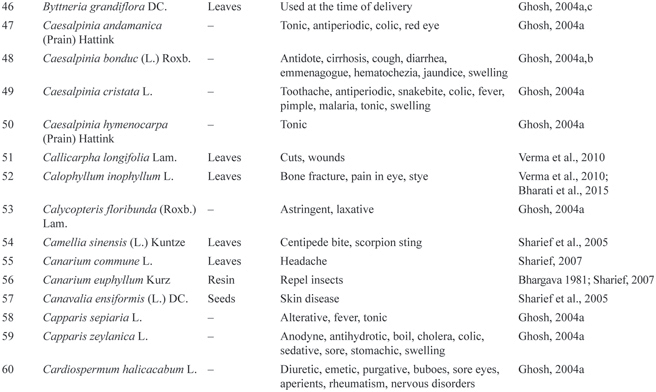

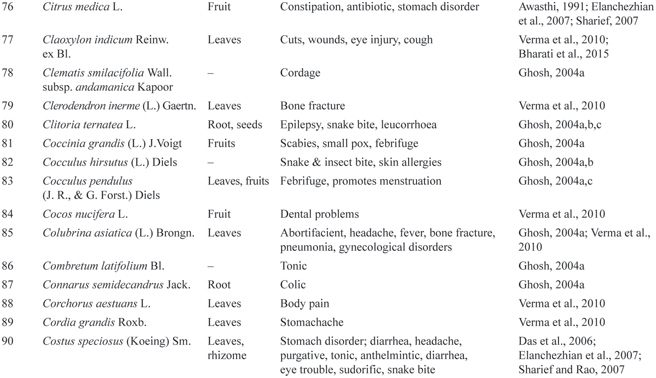

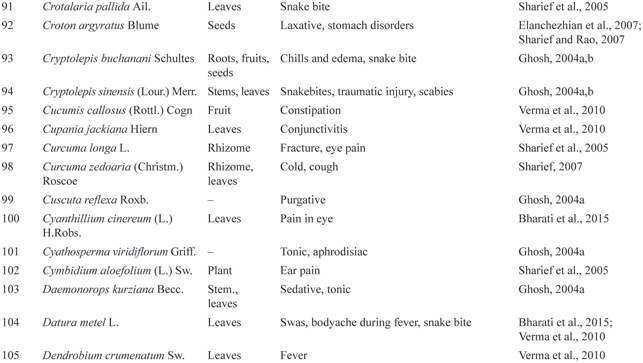

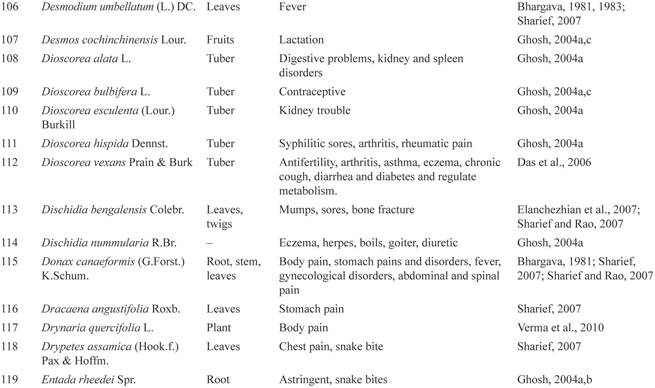

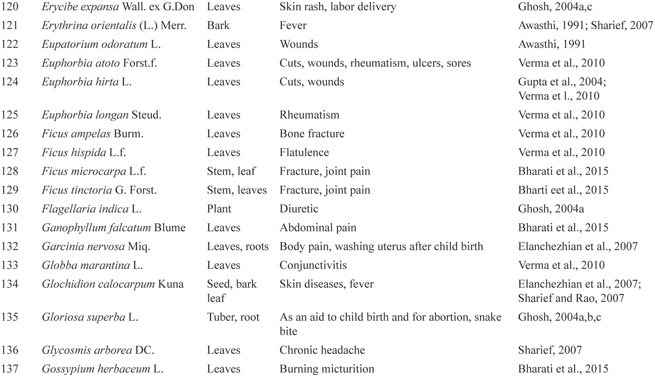

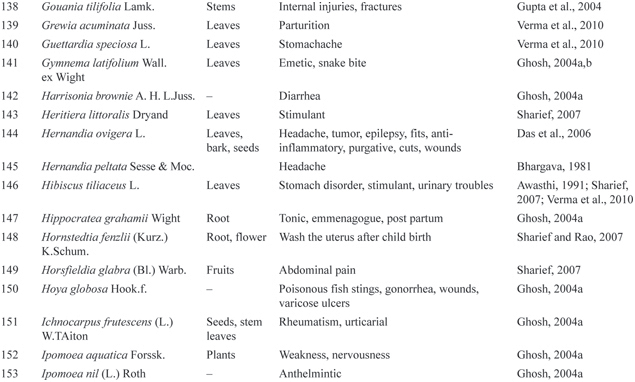

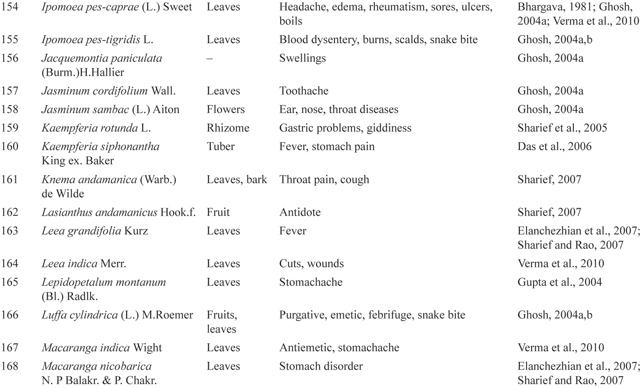

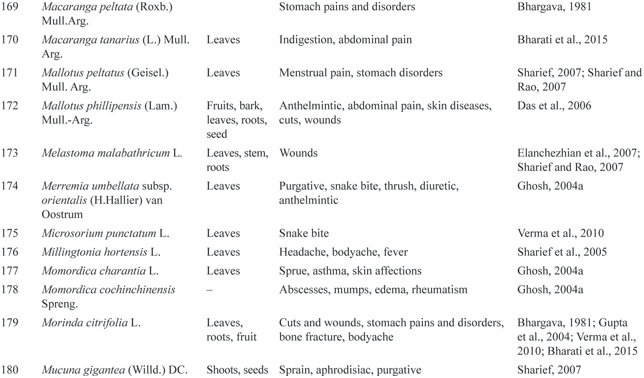

Ethnic tribes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands use various plants or plant parts as a source of food, shelter, clothing, medicine, timber and for other miscellaneous purposes (Table 8.1 and 8.2). Ethnic tribes inhabiting the interior forest of the Islands are mainly forest people and their relationship

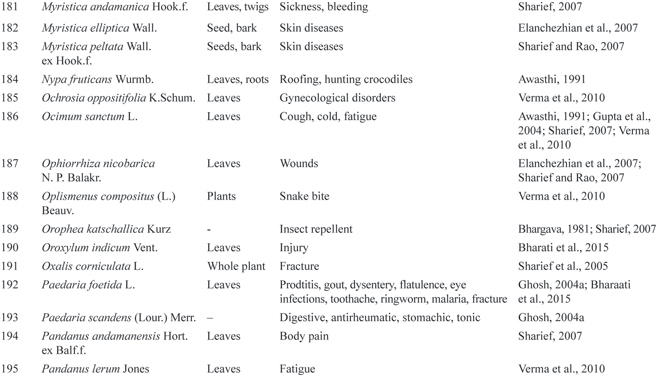

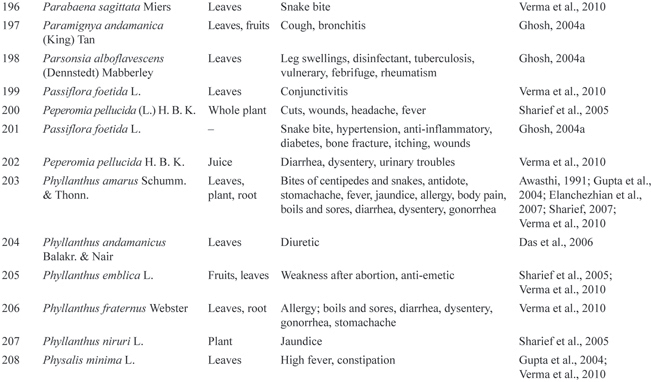

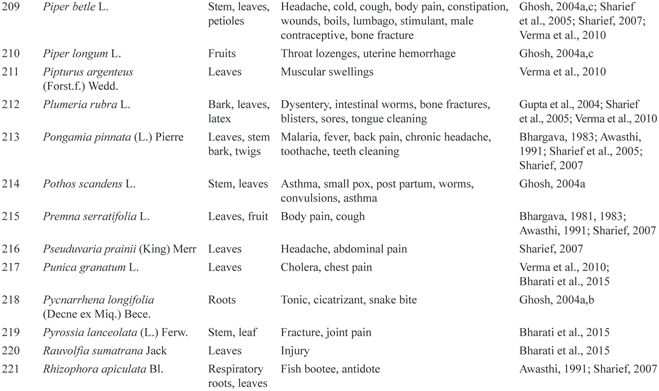

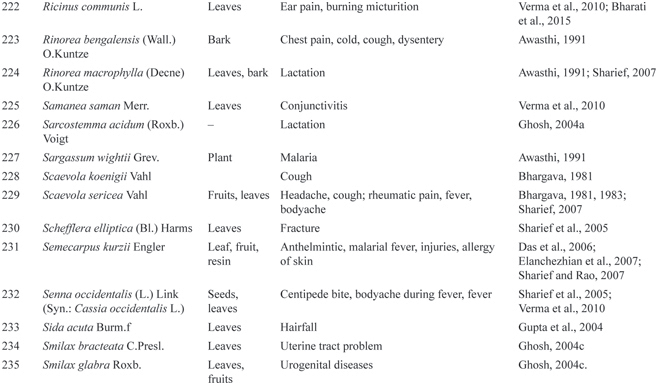

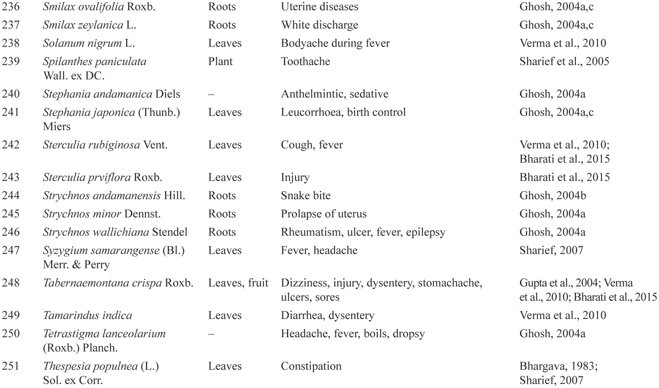

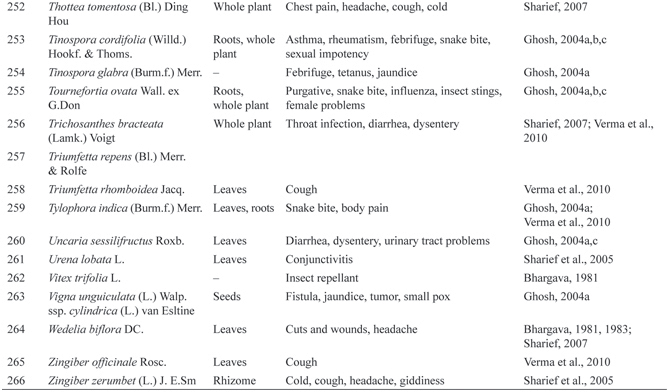

TABLE 8.1 Ethnomédicinal Plants Used by Ethnie Tribes of Andamans

with forest is in a balanced state. They live in cohesion with the nature with least or negligible disturbance to the fragile ecosystem. The tribes depend completely on the forest and marine resources for their livelihood. The semi-nomadic nature of these tribes within the forest area, allow them to use the resources judiciously without over exploiting them.

Dagar (1989) documented uses of 73 plant species as folk medicine used by Nicobarese tribals of Car Nicobar Island. Dagar and Dagar (1991) reported the use of 65 plant species as folk medicine among the Nicobarese of Katchal Island. Dagar and Dagar (1999) gave a detailed account of plants and animals used by Negrito and Mongoloid tribals of Andaman and Nicobar Islands in their routine life for food, shelter, dugour canoe making, taboos, rituals and medicines. Kumar et al. (2006) gave the ethnobotanical profile of 197 species used by the Nicobarese tribe. Prasad et al. (2008) reported that rural folk of North Andamans are using 72 plant species for curing 42 ailments. Ethnomedicinal uses of 289 plant species used by the aborigines in Andaman & Nicobar Islands have been documented by Pandey et al. (2009). Rasingam et al. (2012) gave the details of 11 plant species used as herbal tooth sticks used by the Chota Nagpuri and Tamil inhabitants of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Chander et al. (2014) reported use of 150 medicinal plant species to treat 47 different medicinal uses, divided into nine categories of use. Chander et al. (2015a) recorded the use of 132 medicinal plant species for treating 43 ailments among Nicobrese of Nancowry group of Islands. Chander et al. (2015b) reported uses of 34 medicinal plant species to treat a total of 16 ailments by the Nicobarese inhabiting Little Nicobar Island of Andaman & Nicobar Archipelago. Chander et al. (2015c) documented the use of 78 medicinal plant species to treat 38 different ailments among Karens of Andaman & Nicobar Islands. Other publications on ethnomedicinal plants of Nicobarese include Dagar (1989) and Dagar and Dagar (1996, 2003).

8.4 OTHER USES OF PLANTS

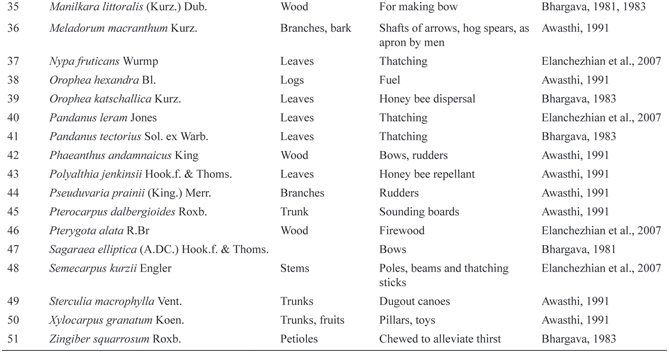

Ethnic tribes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands use plants for various other purposes which are given in Table 8.2.

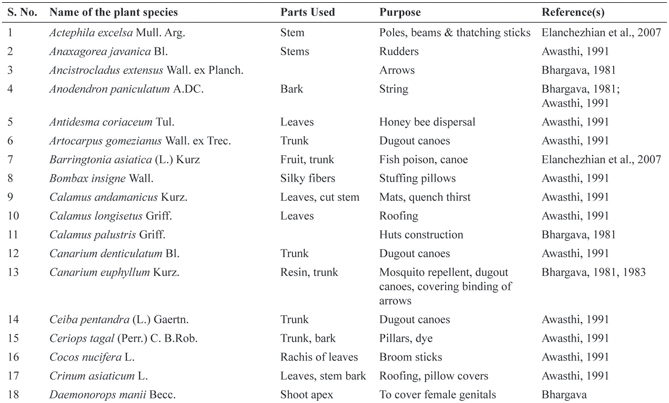

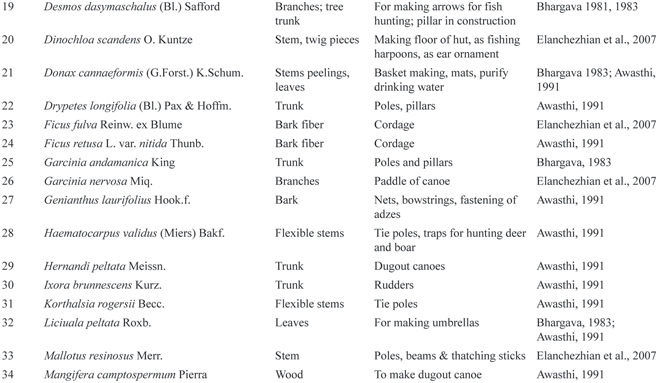

TABLE 8.2 Miscellaneous Etlniobotanical Uses by Ethnie Tribes of Great Nicobar Islands

8.5 ETHNIC FOOD PLANTS AND ETHNIC FOODS OF THE ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS

8.5.1 DIVERSITY OF FOOD PLANTS

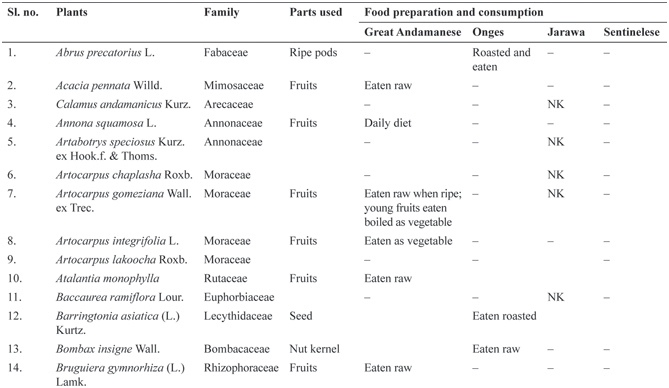

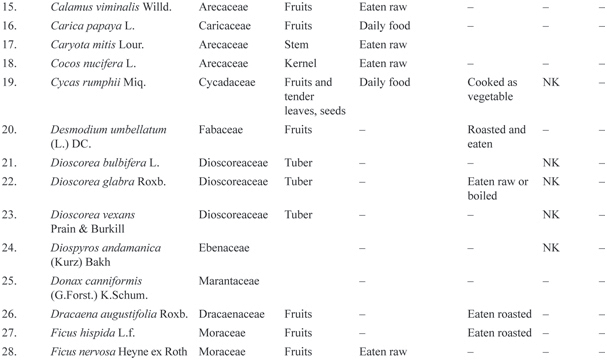

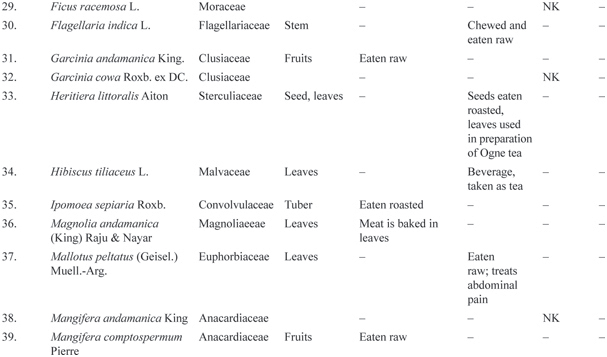

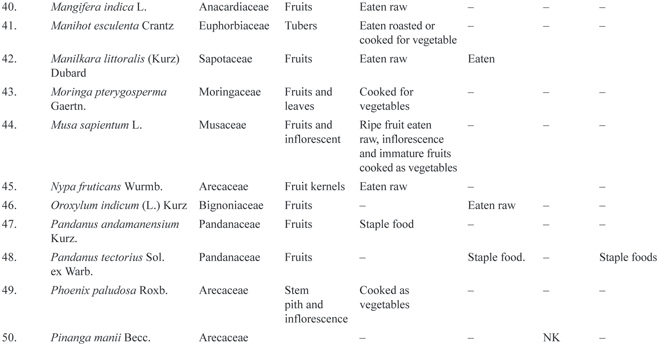

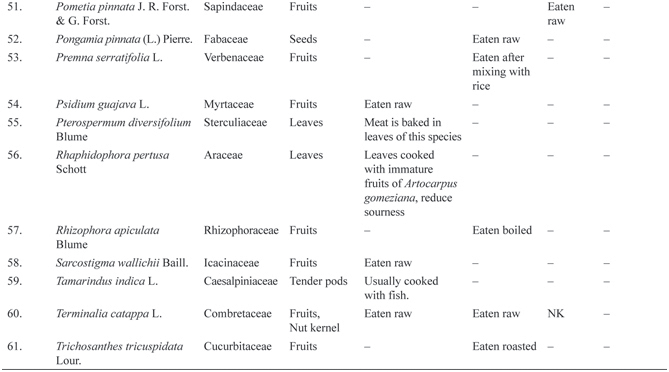

There are limited reports on ethnic food plants of indigenous tribes of the region. Works on the culture and tradition as well as ethnobotany of the aboriginal tribes of the Andamans has been carried out by a few anthropologists who have made some references to plants used by the tribal folks (Klos, 1902; Chak, 1967; Singh, 1975; Cipriani, 1996; Balakrishnan, 1996; Kashyap et al., 2003; Patnaik, 2006; Singh et al., 2007; Krishnakumar, 2009; Seksharia and Pandya, 2010). Some authors reported dietary utilization of plant resources by indigenous people of Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Thothathri, 1966; Awasthi, 1991; Sangal, 1971; Chengappa, 1958; Joshi, 1975; Sahni, 1953; Anonymous, 1948-1972; Bhargava, 1981, 1983; Raghunathan, 1976; Watt, 1990; Zama, 1976; Shareif, 2007; Singh and Singh, 2012). The chief reason for scarce ethnobotanical information could be because only the Great Andamanese and Onge regions are accessible for outsiders while the Jarawa and Sentinelese peoples are still hostile (Awasthi, 1991). The indigenous tribes of the Great Andamans have great affinity towards wild foods, particularly they are acquainted to consumption of wild fruits. Perhaps, with long association with forest and meticulous observation of plants and animals, they have gained knowledge on the poisonous and non-poisonous forest products. Some of the foods are eaten raw while some are eaten either in cooked form or eaten roasted. The people are also aware of quenching their thirst through chewing stems of certain plants like Flagellaria indica or sometimes chew petioles of Zingiber squarossum to alleviate their thirst. Available data on food plants of the indigenous tribes of the Great Andamans is presented in Table 8.3. A total of 61 edible plants belonging to 37 botanical families have been compiled. A glance of the enumeration reflects the foods are minimally processed and no great efforts are devoted for preparing the foods. Plants foods of the Jarawas and Sentineleses are almost negligible; of the few plants consumed by them, the preparation methods are not known which suggest most foods are eaten raw.

TABLE 8.3 Diversity of Food Plants and Preparation by Ethnic Tribes of Andamans

8.5.2 DIETARY SYSTEMS AND CULINARY METHODS

Seafoods form the dominant component of the food system of the Andamanese. They also consume both red and white meat. Being hunters by origin, the people of the islands hunt birds and wild animals and feast on them. Before the use of fire was known to them, foods are said to be consumed in raw form. The region is rich in biodiversity and the inhabitants mainly survive through means of forest and forest products. Forest food includes mango (Mangifera sp.), banana (Musa sp.), orange (Citrus sp.), pineapple (Ananas comosus), guava (Psidium guajava). Fruits of Pandanas leram, P. odaratissimus and P tectorius are common to all the indigenous tribes which also form the staple food of the Andamans. Some forest produce like roots and inner stems of certain wild palm (Pinanga manii) known as komba are also collected for food. All parts of plants (leaves, tender stem, roots, flowers, unripe fruits, spikes and immature seeds) are consumed. Traditional vegetables are consumed after minimal processing viz. cleaning, washing, boiling, frying, grinding, mixing and drying. The cuisines include chutney, fried items, pickles, boiled vegetables, roasted tender stem and mix vegetables. Eryngium foetidum, Moringa oleífera, Hibiscus sabdariffa and Piper serpentum are used to enhance taste and flavor of dietary preparations. The vegetables are also used in making of household snacks like pakora, soup, muruku, vada and maththi. Immature fruits of perennial trees are also used for culinary preparations but their less popularity was primarily due to cumbersome processes of product preparation and lack of availability (Singh and Singh, 2012). There exist differences among local communities for preference of traditional vegetables which might be due to differences in dietary habits and associated food traditions (Majumdar, 1975; Singh et al., 2013).

Ethnic tribes of the Andamans also exploit animal resource as source of food. Small animals and snakes are occasionally hunted for food. Along with this, folks supplement their diet with a variety of marine products, ranging from octopus (known as koe) to multiple varieties of fish. Sea turtles (Eretmochelys sp.) and their eggs are also relished. The tribes are fond of hunting and hunt almost all the small animals such as small rodents, snakes, birds, etc. For hunting larger animals such as wild boars, monkeys and crocodiles, they usually form well-organized groups. Crocodile hunting is very rarely undertaken as it involves grouping of almost all the men and grown-up boys of a band and is a rather dangerous task. Sometimes, the total effort put in at times may result in just injuring the crocodile and in such case the hunt becomes unproductive. Both men and women gather all sorts of edible leaves and root matter; insects and larvae are often included in their collection. Fishing technology is well developed as they have variety of fishing spears which they use in the shallow coral bedded sea fronts where the waters are clear and fish are visible; use of fish net is a common practice. They use outrigger canoes which are large and capable for venturing into deep sea, but generally they use it for short trips along the coast to visit other settlements or nearby islands.

8.5.3 FOOD SYSTEMS AND CULTURE

The Onges prefer to catch sea cow Dugong dugon (a mammal belonging to order Sirenia) for delicious meat and they place the lower jaw of the animal in front of their house to ward off evil spirits. The Great Andamanese are very much aware of the poison of the climber Anodendron paniculatum. The leaves of this plant when eaten by pregnant women is said to cause abortion as the watery-milky juice of the plant is said to be septic. Aromatic resin of Canarium euphyllum is used by the Great Andamanese for burning during certain ceremonies. The people are very much fond of consuming the fruits of Carica papaya while the dried, crushed leaves are used as a substitute for tobacco. The Great Andamanese prepare tea from the mature leaves of Hibiscus tiliaceus, which are boiled in water to get an extract. The tea which blends into a colored and flavored drink is also used for stomach disorders.

KEYWORDS

- Andamans

- Ethnobotany

- Ethnofood plants

- Ethnomedicinal plants

- Nicobar Islands

- Traditional knowledge

REFERENCES

1. Anonymous. (1948-1972). The Wealth of India-Raw Materials, Vols. 1-9; Council of Scientific & Industrial Research; New Delhi.

2. AwasthiA.K.. (1991). Ethnobotanical Studies of the Negrito Islanders of Andaman Islands, India: The Great Andamanese. Economic Bot. 45(2):274–280.

3. Balakrishnan, N. P., & Ellis, J.L.. (1996). Andaman and Nicobar Islands. In: Hajra et al. (eds.). Flora of India, Part 1. Botanical Survey of India, Calcutta, India.

4. BharatiP.L., PrakashO, JadhavA.D.. 2015. Plants used as traditional medicine by the Nicobari tribes of Andaman & Nicobar Islands. Int. J. Bioassays. 4(12):4650–4652.

5. BhargavaN. 1981. Plants in folk life and folklore in Andaman and Nicobar Islands. In: JainS.K., editor. Glimpses of Indian Ethnobotany. New Delhi: Oxford & IBH Publishing; p. 329–345.

6. BhargavaN.. (1983). Ethnobotanical studies of the tribals of Andaman & Nicobar Islands. India I: Onge. Econ. Bot. 37(1):110–119.

7. ChakB.L.. (1967). Green islands in the sea. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, Delhi: Publication Division.

8. ChakrabortyT, BalakrishnanN.P.. (2003). Ethnobotany of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India A review. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. 27(4):869–893.

9. ChakrabortyT, RaoMKV. 1988. Ethnobotanical studies of Shompens of Great Nicobar Island. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. 12:39–54.

10. Chander, M. P., Kartick, C., Gangadhar, J., & Vijayachari, P (2014). Ethnomedicine and healthcare practices among Nicobarese of Car Nicobar an indigenous tribe of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. J. Ethnopharmacol., 158 part A, 18-24.

11. ChanderM.P., KartickC., VijayachariP.. (2015a). Herbal medicine & healthcare practice amng Nicobarese of Nancowry group of Isalands an indigenous tribe of Andaman & Nicobar Islands. Indian J. Med. Res. 141(5):720–740.

12. ChanderM.P., KartickC, VijayachariP. (2015b). Medicinal plants used by the Nicobarese inhabiting Little Nicobar Island of the Andaman and Nicobar Archipelago. India. J. Altrn. Complement. Med. 21(7):373–379.

13. ChanderM.P., KartickC, VijayachariP. (2015c). Ethnomedicinal knowledge among Karens of Andaman & Nicobar Islands. India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 162:127–133.

14. ChengappaB.S.. (1958). Working Plan for the Forests of the Andaman Islands, 1942–57. Port Blair: Andaman and Nicobar Administration.

15. CiprianiL. (1996). The Andaman Islanders. London: Weiden-feld and Nicolson.

16. DagarH.S.. (1989). Plant folk medicines among Nicobarese tribals of Car Nicobar Islands. India. Econ. Bot. 43:215–224.

17. DagarH.S.. (1989). Plants in folk medicine of the Nicobarese of Bampoka Island. J Andaman Sci Assoc. 5:69–71.

18. DagarH.S., DagarJ.C.. (1991). Plant folk medicines among the Nicobarese of Katchal Islands. India. Econ. Bot. 45:114–119.

19. DagarH.S., DagarJ.C.. 1996. Ethnobotanical studies of the Nicobarese of Chowra Islands of Nicobar group of Islands. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. Additional Series. 12:381–388.

20. DagarJ.C., DagarH.S.. (1999). Ethnobotany of aborigines of Andaman-Nicobar Islands. Dehra Dun: Surya International.

21. DagarH.S., DagarJ.C.. (2003). Plants used in ethnomedicine by the Nicobarese of islands in Bay of Bengal. India. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. 27:73–84.

22. DasS, SheejaT.E., MandalA. (2006). Ethnomedicinal uses of certain plants from Bay Islands, Indian. J. Trad. Knowl. 5:207–211.

23. ElanchezhianR, SenthilkumarR, BeenaS.J., SuryanarayanaM.A.. (2007). Ethnobotany of Shompen a primitive tribe of Great Nicobar Island. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. 6(2):342–345.

24. GhoshA. (2014a). Survey of ethno-medicinal climbing plants in Andaman and Nicobar Islands. India. Int. J. Pharm. Life Sci. 5(7):3671–3677.

25. GhoshA. (2014b). Traditional phytotherapy treatment for snakebite by tribal people of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. Indian J. Fundamental Appl. Life Sci. 4(2):130–132.

26. GhoshA. (2014c). Climbing plants used to cure some gynecological disorders by tribal people of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. International J. Pharmacy and Life Sci. 5(5):3531–3533.

27. GuptaS, PorwalM.C., RoyP.S.. (2004). Indigenous knowledge on some medicinal plamts among the Nicobari tribe of Car Nicobar Island. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. 3(3):287–293.

28. JoshiM.C.. (1975). Census of India 1971. Government of India, New Delhi: Choura-A socio-economic survey.

29. KashyapV.K., SitalaximiT, SarkarB.N., TrivediR. (2003). Molecular Relatedness of the Aboriginal Groups of Andaman and Nicobar Islands with Similar Ethnic Populations. Int. J. Hum. Genet. 3(1):5–11.

30. KlossC.B.. (1902). Andamans and Nicobars. New Delhi: Vivek Publishing House.

31. KrishnakumarM.V.. 2009. Andaman Islands: Development or Despoliation? The Intern. J. Res. into Island Cultures. 3:104–117.

32. KumarB.K., KumarT., SelvunB., SajibalaR.S.C., JairajS Mehrotra, PushpangadanP. (2006). Ethnobotanical heritage of Nicobarese tribe. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. 30(2):331–348.

33. MajumdarR.C.. (1975). Penal settlements in Andamans. New Delhi: Ministry of Education and Social Welfare, Govt. of India Press, McGraw-Hill; p. 251–258.

34. PandeyR.P., RasingamL, LakraG.S.. (2009). Ethnomedicinal plants of the Aborigines in Andaman & Nicobar Islands. India: Nelumbo; p. 51.

35. Patnaik, R. (2006). The Last Foragers: Ecology of Forest Shompen . In: PDash Sharma (Ed.): Anthropology of Primitive Tribes. New Delhi: Serial Publications, pp. 116-129.

36. PrasadP.R.C., ReddyC.S., RazaS.H., DuttC.B.S.. 2008. Folklore medicinal plants of North Andaman Islands, India. Fitoterapia. 79:458–464.

37. Raghunathan, K. (1976). Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Recordings of the Medico Botanical Survey Team (CCRIMH-New Delhi), Publ. 19. (Cyclo-styled).

38. RaoP.S.N., MainaVinod, TiggaaM. (2001). The plants of sustenance among the Jarawa aboriginies in the Andaman Islands. J. Forestry. 24(3):395402.

39. RasingamL, JeevaS, KannanD. 2012. Dental care ofAndaman and Nicobar folks: medicinal plants used as toothstick. Asian Pacific J. Trop. Biomed. S1013–S1016.

40. SahniK.C.. (1953). Botanical exploration in the Great Nicobar. Indian Forester. 79:3–16.

41. SampathkumarV, RaoP.S.N.. (2003). Dye yielding plants of Andaman & Nicobar Islands. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. 27(4):827–838.

42. SangalP.M.. (1971). Forest food of the tribal population of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Indian Forester. 97:646–650.

43. SekhsariaP, PandyaV. (2010). The Jarawa tribal Reserve Dossier: Cultural and biological diversities in the Andaman Islands. Paris: UNESCO.

44. ShariefM.U.. 2007. Plants folk medicine of Negrito tribes of Bay Islands. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. 6(3):468–476.

45. ShariefM.U., KumarS, DiwakarP.G., SharmaT. V. R. S.. (2005). Traditional phytotherapy among Karens of Middle Andaman. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. 4(4):429–436.

46. ShariefM.U., RaoR.R.. 2007. Ethnobotanical studies of Shompens A critically endangered and degenerating ethnic community in Great Nicobar Island. Curr. Sci. 93(11):1623–1628.

47. SinghR. 1975. Arrows speak louder than words: The last Andaman Islanders. Natl. Geogr. 148:66–91.

48. SinghS, SinghD.R.. (2012). Species diversity of vegetables crops in Andaman and Nicobar Islands: efforts and challenges for utilization. In: SinghD.R., et al., editors. Souvenir on Innovative technologies for conservation and sustainable utilization of island biodiversity. Port Blair: CARI; p. 120–129.

49. Singh, S., Singh, D.R., Singh, L. B., Chand, S., & Roy, S.D.. (2013). Indigenous Vegetables for Food and Nutritional Security in Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. Intern. J. Agriculture and Food Sci. Technol ., 4 ( 5 ), 503-512.

50. ThothathriK. 1966. The tonyoge plant of Little Andaman. Indian Forester. 92:530–532.

51. VermaC, BhatiaS, SrivastavaS. 2010. Traditional medicine ofthe Nicobarese. Indian J. Trad. Knowl. 9:779–785.

52. Watt, G. (1990). A dictionary of the economic products of India. 6 vol. Periodical Experts, New Delhi. (Reprinted in 1972).

53. ZamaL. 1976. Forestry in the Andamans. Yojana. 20:56–61.