Prologue

Paper was born in Egypt toward the end of the Stone Age and was put to work almost immediately. Paper made from papyrus soon became a necessity for the thousands of scribes, priests, and accountants who made a living from the obsessive recording of temple goods and property, and the agricultural accounting that was part of ordinary life in ancient Egypt. Four thousand years later, after an interesting and varied history, papyrus paper was replaced by modern paper made from rag and wood pulp. The story told in this book is an account of what happened during those early days when papyrus paper was the most common medium used throughout the world.

The making of this kind of paper, and the books and documents that came from it, represents one of the most astonishing and exciting stories in the history of the world. It is a tale of human endeavor that spans a period from the late Neolithic almost to the time of Gutenberg; a period that covers more than three-quarters of recorded history, yet it has never been told in its entirety until now.

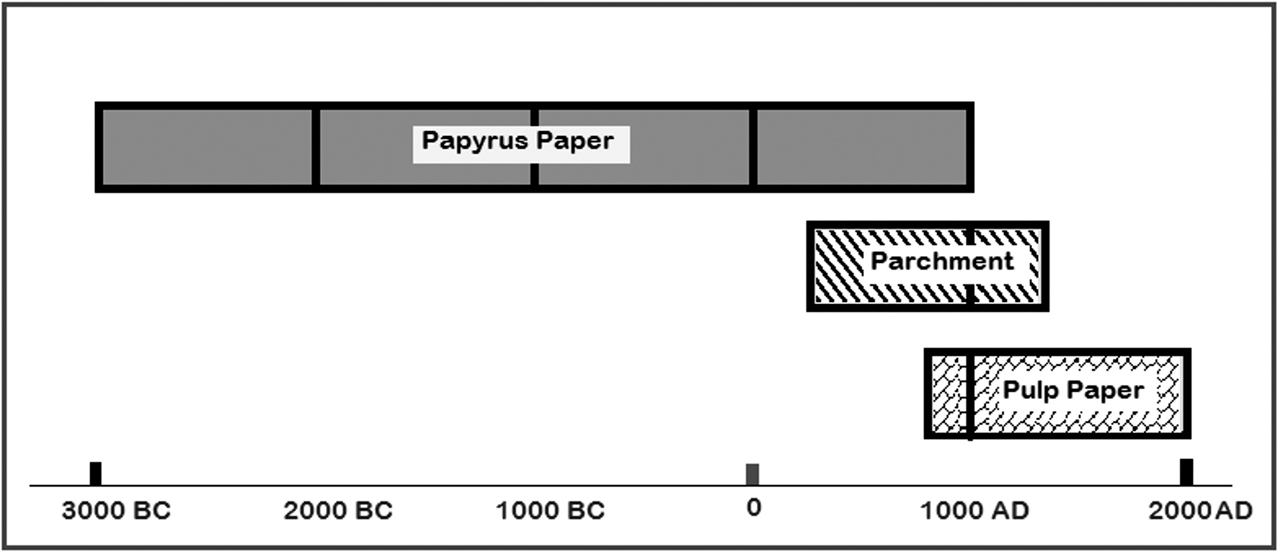

Why not? It seems writers and historians over time have been enamored with the story of parchment and vellum used in place of papyrus in Europe from 300 A.D. to 1450 A.D. And they have also been much taken by the story of rag paper and its discovery by the Chinese. Developed further by the Arabs in 750 A.D. Chinese rag paper evolved into the handmade paper of the Europeans, the sort of paper used by Gutenberg in 1450 and that started the modern age of books and printing. Lost in the shuffle are the early paper products used from the end of the Stone Age until 1450 A.D. What sort of paper did people use for business records, letters, and books during all that time, and why haven’t people written about this?

Comparison—different forms of paper through history.

To begin with, there are no examples of ancient paper before 5,100 years ago. From then until the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, we have thousands of fragments and some small rolls that represent the first records, which include accounts of building materials used for the pyramids in 2566 B.C. After this, one fragile roll of papyrus dated to 1800 B.C. stands out; it contains the first surviving literary effort, the lectures and notes of two viziers of ancient Egypt.

The era of funerary scrolls began around 1550 B.C.; thousands of scrolls and pages of papyrus have been found preserved in tombs dating from that period. These books of the dead, which first appeared in 1700 B.C.,1 were used to guide the deceased in the afterworld. Produced up until the time of Christ, they dominated the world of ancient paper until the literary efforts of the Greeks and later Romans finally provided enough documents and fragments on which historians could begin to feed. Parchment and pulp paper appeared in later years, but the paucity of material and lack of early documents that remained intact meant that the story has been difficult to write about. It was also easy to pass over, so it was lost in the shuffle. It was as if history had dealt out the cards, but had neglected to include several aces in the deck. This present book is intended to restore the balance and to identify the earliest paper as a key element of global cultural advancement.

I have divided this vast history into three parts, in order to capture the rise, apex, and decline of papyrus paper:

1. Guardian of Immortality: ancient Egyptian paper and books, their discovery and significance

2. Egypt, Papermaker to the World: the earliest form of paper, how it was manufactured, how it came to rule the world

3. The Enemy of Oblivion: the ancient Romans’ love affair with papyrus paper, book scrolls, and libraries, early Christian books, parchment, Chinese paper, the rise of rag paper and the printed book.

A second source of inspiration for this book was an illuminating essay by Robert Darnton—historian, writer, Princeton emeritus professor, and former director of the Harvard University Library. The essay first appeared in the journal Daedalus in 1982 and again in The Kiss of Lamourette in 1990, a book I bought because of the chapter on publishing, “A Survival Strategy for Academic Authors.” This last offered some of the best, most practical advice I’d ever gotten about how to get a book published on the ecology, life cycle, and history of the papyrus plant. He especially advocated the two t’s, tactics and titles, which must appear innovative even when the subject is quite ordinary. A good example was the book On the Rocks: A Geology of Great Britain.

Well, once my book was published,2 I moved on to the idea of taking on the task referred to above, how to identify the earliest paper and books as key elements of global cultural advancement. I was encouraged again by my reading of Professor Darnton, this time from his essay in chapter seven, which was about how a field of knowledge could take on a distinct identity. Titled “What is the History of Books?” it put forward Darnton’s argument that the history of books was its own, new, and vital discipline even then in the 1980’s. This idea resonated with me as I set out a few years ago to write this present book.

Darnton made much of the purpose of those in pursuit of this new discipline, which would help them understand how exposure to the printed word affected the thought and behavior of mankind, before and after the invention of movable type. In essence, the goal of any such endeavor should be to understand the book as a force in history. In my case, I felt that the study of the earliest books—those made of the first “p’p’r” paper of the ancients, which came from plants growing in the swamps of Egypt and was preserved for us by the hot, dry sands of the Nile—were as of yet underrepresented.

Is the study of the history of books worth it? After all, some might argue that books and paper, which are the objects of my story, are on their way out. Well, not quite. Darnton and many others (including, as he points out, Bill Gates) prefer printed paper to computer screens for extensive reading. In short, Darnton assures us, the old-fashioned codex printed on folded and gathered sheets of paper is not about to disappear into cyberspace.

Darnton warned anyone who might set out along the path that led to the understanding of the book as a force in history, that they would have to cross a no-man’s land located at the intersection of a half-dozen fields of study. The ancillary disciplines to be considered included the histories of libraries, publishing, paper, ink, writing, and reading. One question that arose immediately from my perspective is that I often think of books and paper as Media One.3 This set aside paper, as I see it, as an invention that lent itself to the long-term needs of modern man. It also distanced paper from the many antique media used in earlier times that were less than global or of limited use because they were so cumbersome.

What then was Media Two? The answer to me was clear; Media Two was the second media invention that was of great service to modern man: the telegraph. More accurately, the long-distance transmission of text messages without the physical exchange of Media One or any other object bearing the message. Thus, as Wikipedia tells us, semaphore (a system of flag waving) is a method of telegraphy, whereas pigeon post is not.

The first big break in Media Two came in the nineteenth century with the invention of electrical telegraphy, then wireless radio, all of which were followed by a second big break with the arrival of natural language interfaces. This happened in the Internet Age and allowed for the evolution of technologies such as electronic mail and instant messaging; these are all still part of this second phase of information transmission, divorced as it is from the physical exchange that paper represents. Paper was the first innovation that allowed for the true expansion of the human intellect and its creative, expressive, and even moral possibilities. No wonder it is still considered a key element in global cultural advancement.