The Inspector Puts Pen to Paper and Makes History

Our story begins in the last year of the reign of Pharaoh Khufu (2589–2562 B.C.) His Great Pyramid was almost complete and it was no coincidence that his life would end perhaps at the moment the last stone was put in place. It was well within his power to do whatever he wanted, after all; he was a god on earth, was he not? In the last year of his existence and in his haste to have all in readiness for his death, he may have driven the people of his realm to work harder than usual. As king and overseer of the known world, he would probably never brook riots or insurrections; in any event he had no need to worry in that regard, since he had several very efficient management techniques that served him well. And, god or no god, good management has a way of winning out.

Great Pyramid of Cheops during the inundation (Wikipedia).

Though labeled a tyrant by Greek historians, Khufu reminds us more of a velvet glove than an iron fist. Firstly, his call to workers to report each year to build his pyramid would always be obeyed. And why not? The supply of meat, beer, food, and living conditions—including medical care—at Giza were all of an unusually high level and quality for that age.1 Consequently, there was no need for slave labor. Khufu’s people came voluntarily by the thousands to work willingly on his monumental constructions in order to insure their own afterlife.2

The work also coincided with the inundation, a period when farm work was at a minimum anyway, so why sit around waiting for the floodwater in the fields to lower enough for planting, when beefsteaks and beer could be had at Giza? It also happened that in that same season, building blocks for his pyramid arrived in quantity daily at the pyramid river port. High water on the Nile worked well for the heavy wooden barges used to transport these enormous stones. Everything functioned in favor of the king, as it had done for Egyptian royals for hundreds of years.

In addition to working conditions and the timely arrival of supplies, Khufu’s management style and choice of staff were faultless. Proof of this lies in what he left behind, the Great Pyramid, engineered to within 0.05 degrees of accuracy along a north-south axis. A magnificent creation to his memory, this tombstone was composed of 2.3 million massive blocks and completed within twenty years.3 It is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World that remains.

We are concerned here with one of Khufu’s managers, an inspector named Merer, a functionary brought into the news in 2013 by Professor Pierre Tallet of the Université Paris-Sorbonne. Merer, until then an unknown leader of a royal team of expeditors, became famous when he was discovered to be the author of the oldest surviving writing on paper in the history of the world.4

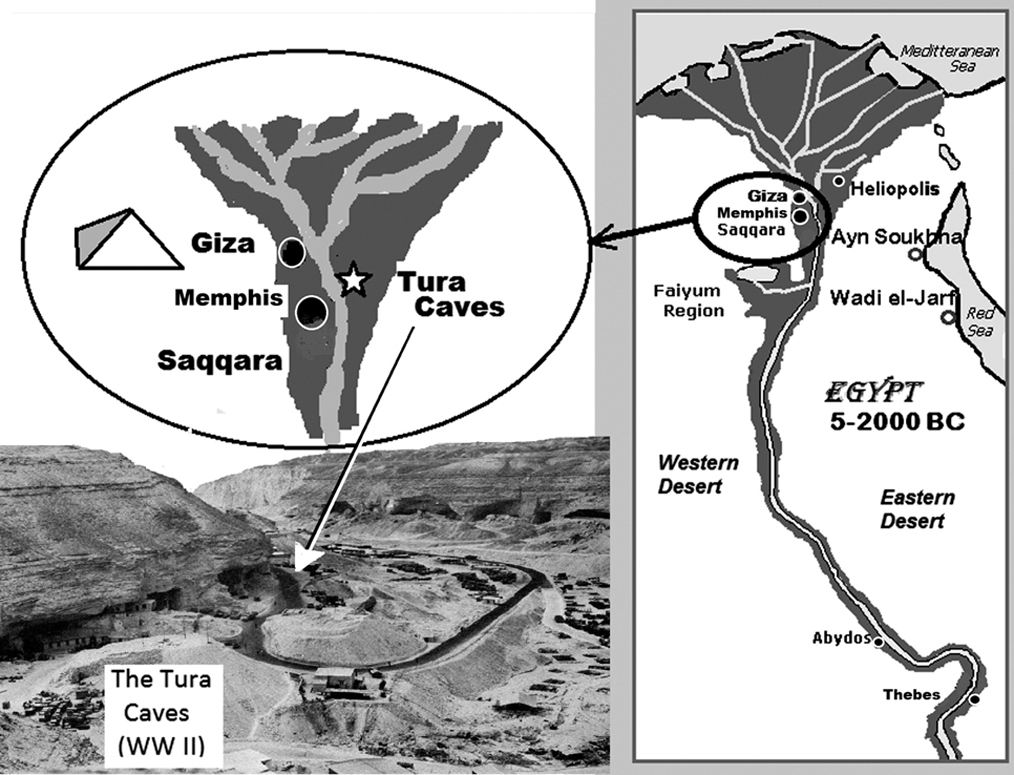

He had been appointed by Khufu to oversee the acquisition and transportation of stone for the Great Pyramid. The stone Merer delivered was a special white limestone from the Tura caves not far from Cairo. Polished with fine sand, this limestone served as the outer covering of the pyramid and turned the outside into a blinding white surface that must have been spectacular when the sun hit it during the height of the day. No wonder people in those days as well as today thought that this pyramid might have come from heaven or outer space—no ordinary man was capable of such things. Of course, they had not counted on people such as Khufu or Merer.

The limestone from Tura was the finest and whitest of all the Egyptian quarries, so it was used for facing the richest tombs, pyramids, sarcophagi, and temples. It was found deep underground and the caves that the quarries left behind were adapted by British forces during World War II to store ammunition, aircraft bombs, and other explosives.

MAP 1: Egypt during the Old Kingdom and the Tura Caves.

Tallet found Merer’s diary during an expedition in 2013 to Wadi el-Jarf, an ancient Red Sea port (Map 1) used by the Egyptians thousands of years ago.5 Tallet was leading a joint Egyptian–French archaeological team with Gregory Marouard from the Oriental Institute of Chicago. The site of the ancient port is in a remote part of the Egyptian desert about 140 miles east of Giza. It consists of a 492 foot-long stone jetty, a navigational marker of heaped stones, a large storage building, and a series of thirty galleries carved into limestone outcrops farther inland from the sea.

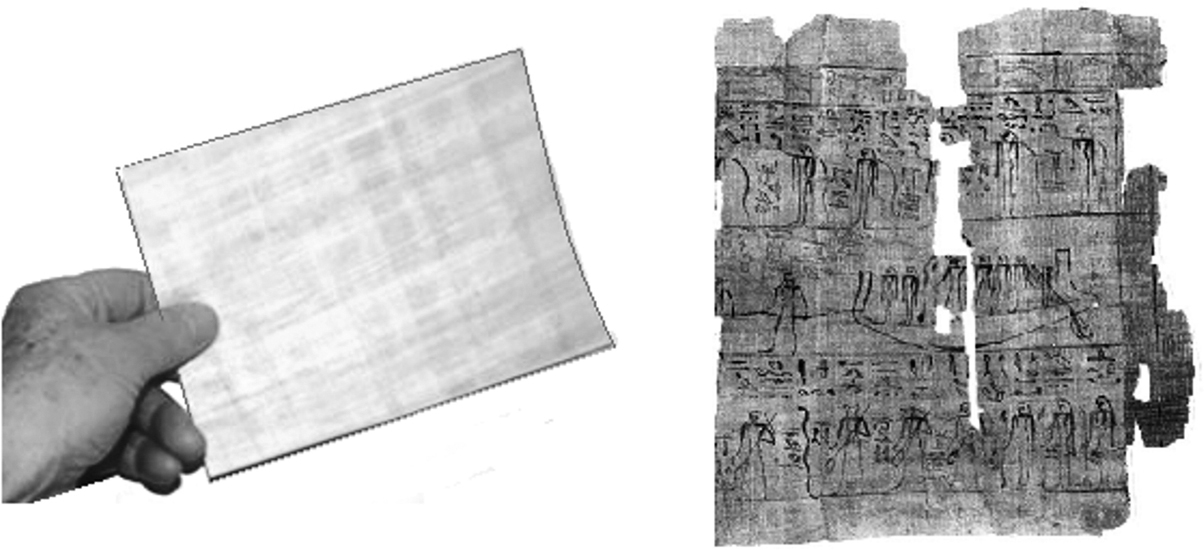

Modern sheet of papyrus paper, left; Ancient papyrus paper 1075–945 B.C., right (after Wikipedia & Brooklyn Museum).

These galleries provided living space, as well as workshops, boat storage space, and warehousing in ancient times; after being abandoned for so many years these were the last places anyone would expect to find an antique diary. But it was in two of these rock-cut galleries that Professor Tallet found an unusual cache of old paper. At first glance, he saw that they were written in hieroglyphics as well as hieratic, the cursive script that the ancient Egyptians used for everyday communication. When Tallet was asked how he felt when he came across these hundreds of pieces of ancient papyrus paper, he replied, “You know, when you are working full tilt every day on a site like that it’s difficult to realize the full significance of such a find.”

Tallet also told Discovery News, “Although we will not learn anything new about the construction of the Khufu monument, this diary provides for the first time a look into what was going on behind the scene.” After examining hundreds of fragments, along with some larger pieces, sheets, and even scrolls, Professor Tallet concluded that the paperwork was the production of Inspector Merer and his team, an efficient group of workmen, scribes, craftsmen, sailors, and stevedores. What was such a group doing in Wadi el-Jarf? Tallet concluded that Merer and his team had been sent there by royal command to collect and transport copper back to Giza.6 At that time, copper rivaled gold in terms of utility and value as a trade item. Khufu lusted after the output of local copper foundries. Why? Because copper was used in forming the tools his pyramid builders needed. Indeed, according to some, Khufu may have amassed the largest concentration of copper anywhere in the world in order to have the tools needed to build his gigantic marvel.7 The production of thousands of copper tools required in turn a large amount of wood needed to produce the hot fires necessary for working the metal. In fact the construction of the pyramids at Giza must have used so much wood that deforestation of the Giza region was inevitable, especially because acacia trees—the preferred fuel—were not easily replaced because of the arid conditions that developed in this region.

The metal came from several sources, including the Sinai region that lies just across the Red Sea, opposite the ancient ports of Ayn Sukhna and Wadi el-Jarf. At Ayn Sukhna, Professor Tallet had uncovered the remains of ovens for smelting copper before he discovered Merer’s journals.8

Khufu was also known to have sent several expeditions to Lebanon to trade copper tools and weapons for precious Lebanese cedar; the wood was essential for building the stately funerary boats that he sequestered in large pits on the southern side of his Great Pyramid.9

It is evident that Merer and his team were important links in the trade and development of Egypt. And this royal team had to be supplied and fed while on the road. Now, thanks to Tallet, we have detailed daily and monthly accounts kept by the team of the foodstuffs they received and consumed. Local officials had to provide for them since they were on assignment from Pharaoh. The names of those contributing to the maintenance of this team were also entered on the sheets, perhaps serving as an official receipt to let Pharaoh know exactly how the various provinces were carrying out their obligations. There is an entry for every item that had to be delivered to the team. On the papyrus account sheet, alongside the accounting of food and supplies, Merer and his clerks drew three boxes: one to indicate the amount anticipated, then an entry of what was actually delivered, and finally what was still pending. The most complete of these sheets was the delivery record of different types of cereals, or the “account of bread.”10

A second set of documents discovered by Professor Tallet consists of time sheets, grids with horizontal lines subdivided into thirty boxes with columns to record the daily activities of the team over the course of a month. This mostly concerns their progress fetching limestone slabs at Tura and delivering them to Giza. The team scribes entered tasks and project goals on lists separated by horizontal lines. At every stage of the operation, a notation of progress or date of completion would be added to track overall progress. Forward progress was definitely needed to satisfy the boss, who in this case was a pharaoh with a reputation for quick and harsh reactions.

Sound familiar? Michael Grubbs of Zapier thought it was. He cites Merer’s bread account and time sheets as the first ever spreadsheet.11 Apparently, four and a half thousand years ago man was just as bad at mentally processing information as today. In modern times we repackaged data tables—more commonly known today as spreadsheets—to organize arrays of information as accurate, easy-to-use data sets that our brains can’t otherwise recall. But the invention of the first “spreadsheet,” as it were, was not thanks to Microsoft Excel, but to papyrus.

Spreadsheets help us sort and label in a way that makes sense, so we can reference it and perform calculations later. The practice actually dates back thousands of years, to the papyrus spreadsheets in the diary of Merer, an Egyptian Old Kingdom official involved in the construction of the Great Pyramid of Khufu. Back then, paper was one of your only options for cataloguing huge amounts of data. Now, we’ve got computers to do the work for us. (Michael Grubbs, “Google Spreadsheets 101: Beginner’s Guide.”)

Lastly we come to the third set of papers found at the site, the journal or diary, which consists of the best-preserved sheets in the cache. They contain detailed accounts of various missions carried out by the Merer team, mainly their work before their arrival at the port of Wadi el-Jarf. The team organized the loading, transport, and delivery of stone from Tura, and thus Merer made daily entries of the times of arrival, overnight stays, and the duration of each phase of the operation.

The Tura quarry is located twelve and half miles south of Giza. From the diary it is clear that the trip required two days to reach Giza sailing with the current. Once unloaded, the barge would be rowed or sailed back upriver and returned to Tura in one day. Recall that unlike the majority of the world’s rivers, the Nile flows north. Sailing on the Nile is at most times an easy task for a light boat; little effort is involved either way. The prevailing wind is from the north, thus boats can sail upstream and then drift down with the river current on their return journey; or in Merer’s case, just the opposite. This is easy to remember when you think of the hieroglyph for the expression “travel up the river or south,” which is a small drawing of a papyriform boat with sail set. The same glyph with sail furled is used to mean, “travel down the river or north.”

One complicating feature of river travel in ancient times was that the course of the Nile shifted, so that the route from Tura to Giza most certainly would not be as direct as it is today. It has been suggested that Khufu and those before him constructed waterways and canals that connected the pyramid-building area to harbors, reservoirs, and basins that would ease the passage of stone barges to the site.12

As noted by Tallet, the diary makes for straightforward reading.

“Day 24: heaping up of stone with the crew, personnel from the palace, and the noble Ankhaef [a vizier, half-brother of Khufu].”

“Day 26: ship laden with stones; spends the night beside the Lake of Khufu.”

“Day 27: departure, bound for the Horizon of Khufu [aka the Great Pyramid] to deliver the stones.”

“Day 28: departure, headed for Tura Caves.”

“Day 29: day spent with the crew to pick up other stones at Tura . . .” and so on.13

Tallet speculated that Merer’s team carried the paperwork and diary with them to the port during their last copper run, then left it all behind when they heard Pharaoh had died. With Khufu dead, their work came to an end. By then, the pyramid was perhaps complete and there was no longer any reason to stay in Wadi el-Jarf, which being an arid, very hot isolated station was hardly a place to linger.14

Tallet was interviewed in 2015 by Alexander Stille, an author and professor at Columbia’s School of Journalism. Stille thought the professor found the comments of the press and popular media both amusing and mildly annoying. And who could blame him for being annoyed? Ealier Tallet had made the case for Merer’s diary being, “. . . to this day the oldest registered papyrus ever unearthed in Egypt,”15 a fact that seems to have been pushed aside by Madison Avenue-type spinmeisters in the popular media. In their view, ancient Egypt means only the “three M’s”: monuments, massive pyramids, and mummies. As far as they are concerned the real keys to development, the mundane items of ordinary life that made Egypt great and are studied by the professor, can go begging. Things like pottery kilns, copper smelters, simple water-lifting devices, homemade ploughs and farm animals like oxen for agricultural production, all must wait. The building of monuments and pyramids are more buzzworthy.

It is true that the pyramids provided a national economic stimulus and a focus for mobilization of resources, but economists tell us that the real basis for Egypt’s greatness came from agriculture and the management of agricultural production. The Egyptians remeasured and reassigned land after every inundation based on past assignments, they assessed expected crops, they collected part of the produce as taxes, and then stored and redistributed it to those on the state’s payroll. Regional storage facilities with hundreds of storehouses provided produce in case there was a shortfall. All of this was recorded and tracked using spreadsheets, and so the country soon became a nation dependent on lightweight paper to process and manage data sets.

Paper thus became one of the many basic things that made Egypt the wonder of its time. Spreadsheets of the type used by Merer became invaluable to the Egyptian way of life. It was also the medium used to record the immediate thoughts or sayings of the priests, pronouncements of the kings, and the substance of history in the ancient world. As such, it was far more important than Khufu or his pyramid. In essence it was the pharaoh’s greatest treasure.

Professor Tallet has spent twenty years working on the edges of Egypt’s ancient culture, a culture that leveraged what Stille calls, “a massive shipping, mining, and farming economy” needed to propel their civilization forward. Part of this process involved the small miracle performed by Merer every day of his adult lifetime, using paper to free up the minds of his team members for bigger and better things. Lightweight paper made from plants helped carry out the business of the moment and, most importantly, helped process and use data sets to move the agenda of Pharaoh forward. All of this pointed again toward the importance of paper.

Paper wasn’t their only means. Other media, such as tablets made of lead, copper, wax, and clay; pieces of shell or pottery; tree bark; leather; cloth; slips of bamboo; and palm leaves were all used to a greater or lesser extent. Papyrus paper was, however, the first medium in the modern sense. It weighed almost nothing, and yet allowed the writing that had until then been restricted to the walls of tombs or sides of monuments or lids of coffins or the impressed surface of clay and paintings on pottery to lift off and take wing. This was the first stage in the ultimate journey that brought us all to what is known today as “the cloud.”

In earlier times, clay tablets were also a means of passing text around. Evolved from tokens used around 4000 B.C. to record basic information about crops and taxes, clay tablets allowed for the development of Sumerian cuneiform ‘wedge writing,’ a script that began around 2500 B.C. The fragility and weight of clay tablets were liabilities that were not shared by paper or parchment. Properly baked clay is fairly permanent, but sun-dried clay is not. New Testament scholar Robert Waltz tells us that a number of cuneiform tablets from Mesopotamia, while initially perfectly legible, are now decaying because they were displayed in museums that did not maintain proper humidity. This quality would preclude their spread after the Bronze Age to areas other than arid regions. These tablets did serve well in the royal archives of Mesopotamia. Distinguished librarian and scholar Frederick Kilgour noted that 95 percent of the half million tablets surviving today were made for record keeping. But there were complaints from ancient readers that the writing used was almost unintelligible to scribes other than the Sumerians. And as a social medium, clay tablets had another disadvantage: their weight. Waltz estimated that a complete New Testament would require about 650 tablets and would be too heavy for an ordinary person to carry, plus you’d need a way to keep the tablets in order.

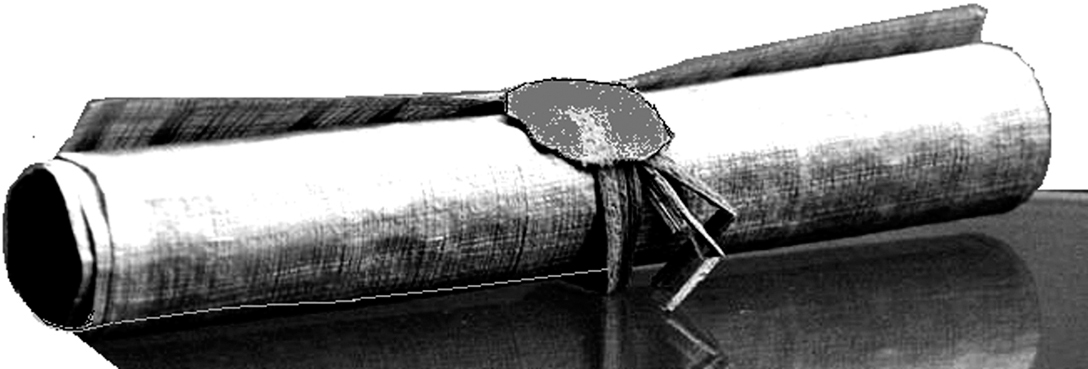

Luckily for the written word, papyrus paper arrived in about 3000 B.C. just in time to help kick-start Western civilization and literature as we know it. From then on, as cuneiform clay tablets faded into the background, the world could breathe easier as words became as transmittable and as easy to spread as the scrolls they were written on.

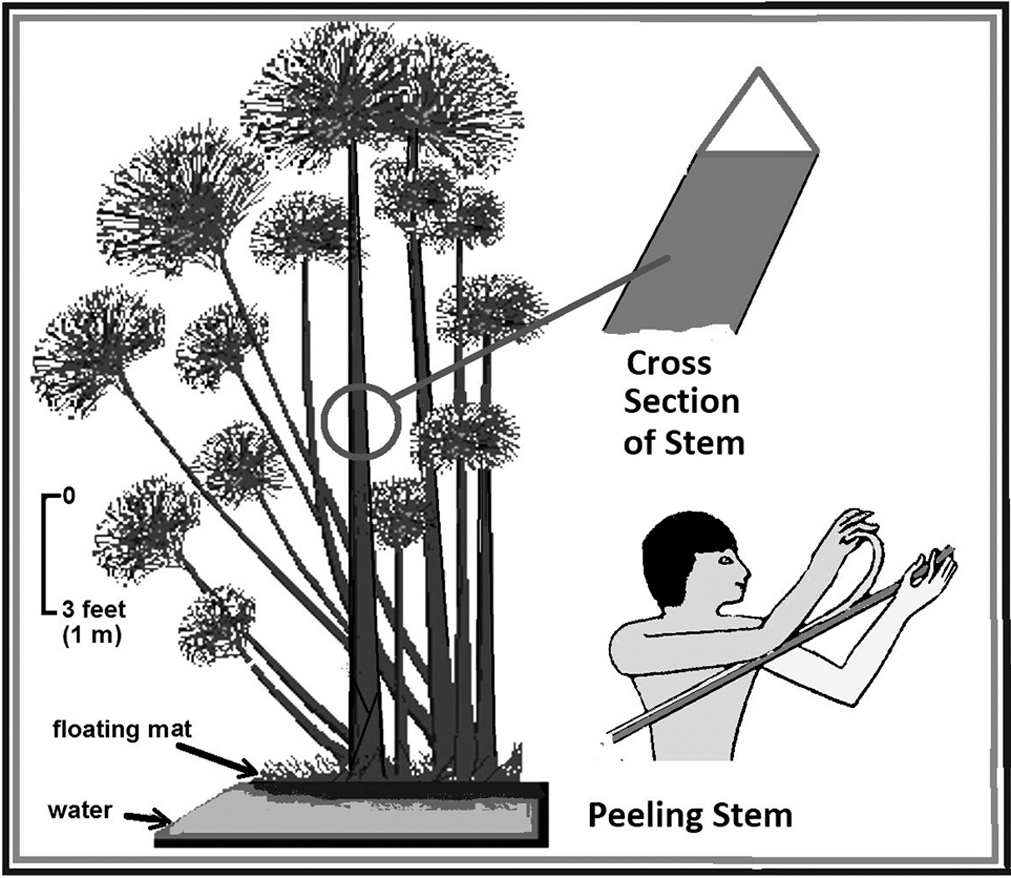

The Egyptians made papyrus paper from thin slices of the white inner stem of the papyrus plant, which were pressed together, and then dried to make millions of sheets. From the end of the Neolithic period in 3000 B.C. the Egyptians, and later the Greeks, Romans, and Arabs, would swear by it.

What a godsend. And the early Christians likewise were relieved when they looked around for something to record their early letters and scriptures on and found papyrus paper in sheets, rolls, and the folded pages of notebooks that formed the earliest books, called “codices.” Lucky for them, and again for us, the plant the Egyptians used was among the fastest growing, most productive plants on earth. Under the hot sun and cloudless skies of old Egypt, it prospered in the ancient swamps, which were millions of acres in size.

The First Piece of Paper Ever

Tallet’s discovery revealed the first piece of paper with writing on it, but we know paper existed even prior to that time. The person who discovered this did so by dint of hard work. With great difficulty, he had cleared tombs of viziers, sacred bulls embalmed and encased in a giant sarcophagi, and Nubian kings, and he had seen it all in the process. He had even been present and lent a helping hand when Howard Carter cleared out the tomb of King Tut in 1923. Solid, reliable, pipe-smoking Walter Emery was there in Saqqara because he had earned the right. On a Penguin book cover, his smiling face looks out from eyes framed by horn-rimmed glasses. Dark haired and ruddy cheeked, in the photograph he looked exactly like what he had been in early life: a marine engineer. But the place where he stood that day late in March 1936 was very far from any ocean or sea; it was an arid, dusty necropolis, a place used in ancient times by the inhabitants of Memphis, the capital that lay south of present-day Cairo.

As a young Egyptologist, Emery had shown himself capable of managing large and important excavations, and because he was a trained draftsman and analyst of structures, he was the right man to excavate these tombs. And his wife Molly helped immensely by taking charge of the camp logistics. The famous archaeologist Flinders Petrie had himself wanted to “do” Saqqara, but had been turned down. In the early days when Petrie had longed for the area, it had been set aside as a preserve for government archaeologists. Many years later the chief inspector of antiquities at Saqqara died and Emery was put in charge.

His first excavation season began in the autumn of 1935, once the hot summer had passed. His first move was to look long and hard at the solid, massive mastaba called “Tomb 3035,” a mound that dominated the area. His engineer’s eye told him that, of all the places in the necropolis, this was the right place to start.

It was rumored that it was the burial place of Hemaka (ca. 3100 B.C.16), an important man who had been chancellor and royal seal-bearer and second in power only to Pharaoh Den in the First Dynasty. This tomb was considered a masterpiece of architecture, and throughout history had attracted many visitors who had picked the place clean. Was there anything of importance left? Luck, intuition, and hard work paid off when, after a year’s work, Emery discovered forty-five storage rooms, or magazines.

Then came the hard part, the backbreaking work; carefully clearing each of the forty-five rooms. Starting in magazine A, his crew had proceeded through the alphabet to Z, where he stood this day. Clearance meant 400 men digging, sifting, sweeping, brushing, and even dusting under close supervision. All the previous twenty-five rooms had been cleared, but to date only a handful were found to contain anything of value. In some of the rooms he had discovered ancient oil and wine jugs. Over the last few weeks in magazines W, X, and Y his crew had turned up more and more artifacts. Today in magazine Z they had uncovered a large number of objects, among them an inlaid gaming disc showing hunting dogs in pursuit of a gazelle. Numerous other gaming discs were recovered in Z, along with arrows, tools, flint scrapers, flint knives, and pot seals made of clay. It was in this room he had found the name of Hemaka on two ivory labels and the handle of a sickle.

More than satisfied with his find, he photographed the site. These last three objects had dated the site and given him the confidence he needed to begin drawing a detailed plan for publication. It also meant that he could name and date Tomb 3035 as definitely belonging to Hemaka.

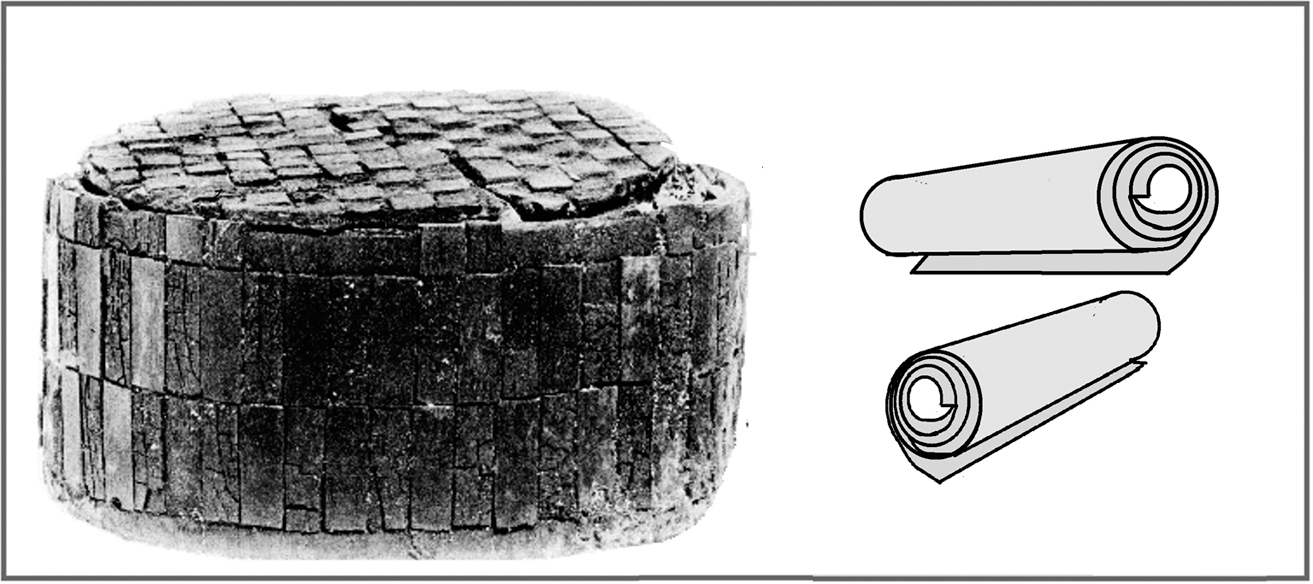

Inlaid wooden box found in Hemaka’s tomb (after Emery, 1938) and two blank papyrus scrolls.

Suddenly one of the workmen motioned him over. There, under a layer of sand and debris, was a small, circular, inlaid wooden box. Carefully hefting the box, he waited as the men gathered round. Here was a container that had sat for over 5,100 years. They were certain that inside would be gold trinkets, semiprecious stones, or some exquisite relict of those early days when history was just beginning. They held their breaths as Emery gently pried opened the lid.

Inside were two rolls of papyrus paper, the sole contents of the box. Imagine their disappointment as they then learned that the rolls were blank. The crew went back to work and Emery turned his attention to other things.

In King Tut’s tomb Carter had his solid gold coffins; in the great Tomb of Hemaka Emery had his drawings, and the largest single collection of early dynastic objects ever discovered, including a cache of 500 arrows. He was satisfied.

The instant he opened the box had been an important moment in the history of the world. Then and now, despite thousands of rolls of papyrus paper recovered from Egypt; thousands of copies of the Book of the Dead; despite two thousand charred rolls found in a villa in Italy; despite the hundreds of thousands of fragments, sheets, and rolls dug up at Oxyrhynchus and other rubbish sites; and the ancient diary and spreadsheets of Merer; no one has yet turned up an older example of paper, let alone two intact rolls. He had by chance uncovered the most ancient paper ever found.

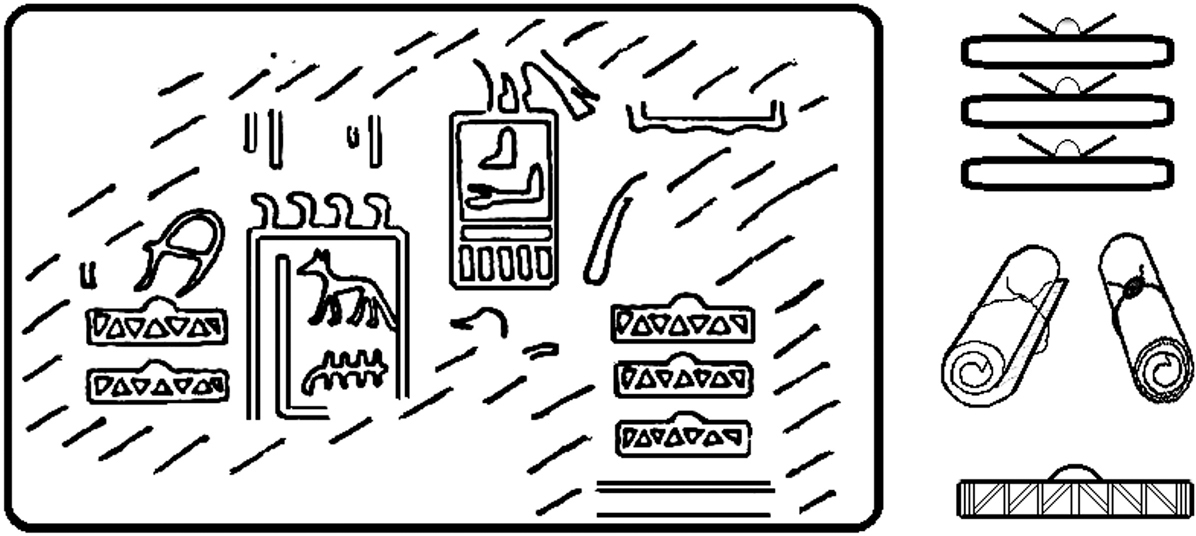

Papyrus roll hieroglyphs on clay seal King Qa’a (from Emery, 1954). Right, various drawings of book rolls and their glyphs.

The most intriguing part of his discovery was that the rolls were blank. What did that mean? During the First Dynasty (3100–2890 B.C.) simple outlines on seal impressions in the time of King Qa’a, the last ruler in this period, showed scrolls sealed with a daub of Nile mud. The drawing of such a sealed scroll served as a hieroglyph for “book” or “writing.”17 This showed that papyrus paper was already in existence with the arrival of the first kings of Egypt. By then Egyptians had developed hieroglyphics, as well as hieratic, an elegant cursive script.

Looking back on all this, Cambridge University Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson concluded that the uninscribed rolls of papyrus paper discovered by Emery were not only proof that papyrus paper existed 5,000 years ago, but also that Egyptian writing already existed in the First Dynasty (a span of eight kings from Narmer to Qa’a from 3150–2750 B.C.)18 Wilkinson based his conclusion on the fact that hieratic script was tied to papyrus paper, which lent itself to this speedier form of writing.

The Pharaohs’ Treasure

It is interesting and important to note from the beginning that ancient Egyptians were quite aware of the true value of the papyrus plant, and that, as it happened, Egypt was the only one among the many early hydraulic civilizations blessed by this plant. This is a fact that seems to have escaped modern historians, and there is precious little in the general or scientific literature to indicate how or why this plant, almost from the beginning of recorded history, was revered and treasured by common folk and the pharaohs.

Papyrus plants growing at the edge of a papyrus swamp on the River Nile.

What made the plant so unusual was the flexibility of its stem. At maturity, most other reeds are too stiff to be worked into a great number of handicrafts or to be made into paper or rope. Once papyrus stems are cut they can be dried and used like any other of the reeds common to the hydraulic empires of Mesopotamia, the Indus valley, Somalia (Shebelle-Juba), Sri Lanka, China, pre-Columbian Mexico, and Lake Titicaca (Bolivia-Peru) to build boats, fences, and houses. Beyond that, the most common reeds are of limited use. It happens that the grass reed or bardi (Phragmites), totora sedge (Schoenoplectus) and the bulrush or khanna (Typha), are all hollow or too rigid at maturity, and therefore not useful for making paper or rope, as was done for thousands of years with the more flexible papyrus.

Given its flexibility, how then was papyrus able to grow up to an average of fifteen feet under normal conditions? The papyrus plant grows a light, tough green skin around a wide triangular core of pith, an ingenious invention of nature that packaged a pith useful for paper making while the outer green skin can be easily peeled away. That in itself provides an excellent source of material for weaving and handicrafts of all sorts. The pith and skin made papyrus an outstanding resource and, because of its size, unique even among plants of its own kind.

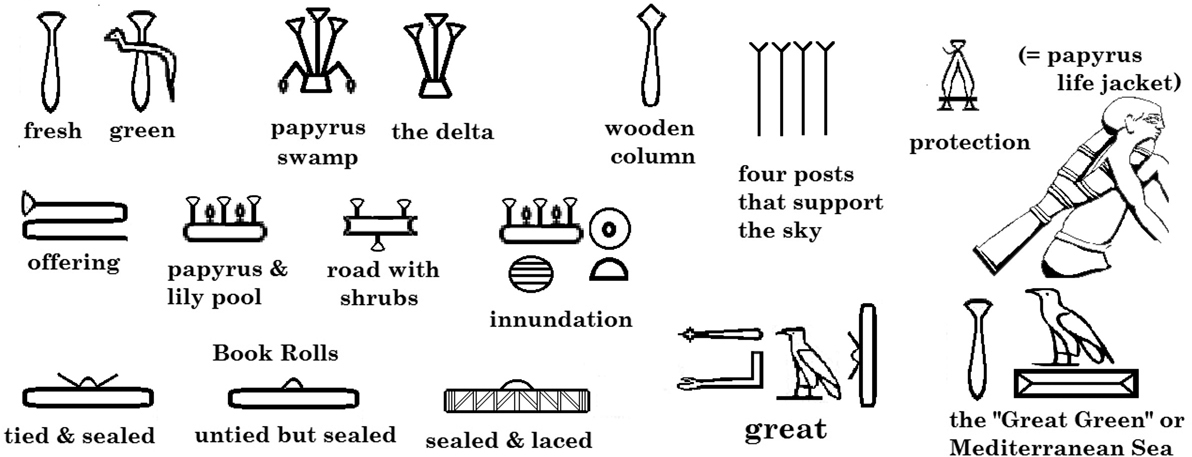

Because of its versatility, productivity, and adaptability, papyrus played an important role in the life of Egyptians and thus appeared in the earliest hieroglyphs. The word for the papyrus stem was “djet” or, as a water plant, “tjufy,” or the more general term for marsh plants, “mehyt.”19 A sign for a papyrus plant was used in writing the word “wadj,” which meant fresh, flourishing, or green—as in the “Great Green” or Mediterranean Sea. After it had been made into paper rolls it was called djema, which meant “clean” or “open,” in reference to the fresh writing surface.20 A long-stemmed papyrus plant folded twice symbolized an offering or gift, a clump of papyrus (phonogram ha) represented the Nile delta or Lower Egypt, stems lined up on a base were used in the expression for the inundation season.

When the papyrus stem was joined with a cobra (the symbol for Wadjet, patroness of the Nile delta), it represented the adjective green (phonogram wadj); whereas stems tied into a bundle then bent into a loop (an early form of life jacket or cattle float) meant “protection.”

Various hieroglyphs featuring papyrus or papyrus paper.

Simple ouline drawings of the plant stem became part of the symbol for a street (perhaps “road with shrubs” was an indication that early Egyptian roads were built along the top of dikes with papyrus plants on both sides or bordering roads that ran between and through papyrus swamps); or the symbol of the four pillars that support the sky, which are the four corners of the earth; or the symbol of the outline of a wooden column modeled after the common stone papyriform columns used in temples throughout Egypt.

Replica roll sealed with clay (Wikipedia & Papyrus Mus. Siracusa, photo by G. Dall’ Orta).

As to the paper, a roll of papyrus paper shown tied with a string and sealed with a daub of clay (or without the string but still sealed) is an ideogram for “roll of papyrus,” with its own phonetic value (“m(dj)3t”). This comes from the fact that hieroglyphic writing is phonetic with certain symbols standing for certain sounds, unlike the English alphabet where some letters have many sounds or can be silent. Thus when an ancient Egyptian said “m(dj)3t” he knew anyone listening would understand that he had just called for another roll of paper.

Combined with other signs, the papyrus roll appears in the expression for “great.” What we are missing, however, is the path that led the Greeks to the word papyros. Several authors believe it is an obvious derivative of the ancient Egyptian “pa-per-aa” (or p’p’r) literally “that of the pharaoh” or “Pharaoh’s own,” in reference to the crown monopoly on papyrus production.

All of the ways that images of papyrus were included in Egyptian writing were indications of how they recognized the importance of the plant. It was almost as if they could foretell that paper that was already being produced from it, would in the coming years be a significant factor in the development of the world. In more immediate terms, it turned out to be an important foreign exchange earner for Pharaoh. It was the export and sale of millions of sheets and rolls of paper, and millions of feet and coils of papyrus rope over thousands of years that made papyrus a treasure—a jewel not shared by any of the other early global river-based cultures. The income from papyrus was a steady, significant flow into the Pharaoh’s coffers. This flow went on regardless of the rise and fall of grain stocks, which were subject to droughts. And the income from the products of Egyptian papyrus swamps could always be counted on. As we will see, it was an unusual set of circumstances that interrupted the export flow of paper.

From 30 B.C. to 640 A.D., Egyptian rule gave way as the Romans took control of the country and the management of the paper industry, which went on to supply the whole of the Roman Empire with scrolls and sheets. One Roman statesman, Cassiodorus, openly admitted that he did not know how the civilized Western world would have got on without it,21 since by his day it was used for books, records of business, correspondence, orders of the day for the Roman army, even the first newspaper, the Acta Diurna—the newspaper that was originally carved on stone—was then written on papyrus paper and became then a lot easier to carry around.

All of this seems to pale in light of the new electronic world of pads, pods, PCs, phones, and tablets. But for all the innovation and technological miracles, the physical proof of evolution of the human mind still centers on the scrolls and books made of papyrus paper, which are counted among the earliest historical documents.

The importance of papyrus’ role was recently reinforced when a scrap of papyrus paper surfaced in 2012 and made headline news. It was announced by Karen King, professor at Harvard Divinity School, that she had obtained a fragment from a private collector who wanted to remain anonymous. It contained the words, “Jesus said to them, ‘My wife . . . ’” King obtained the papyrus two years before that. At first blush, she said, it appeared genuine. “Christian tradition has long held that Jesus was not married, even though no reliable historical evidence exists to support that claim.” King later wondered whether this fragment should lead us to re-think whether Jesus was married, rather than to re-think how Christianity understood sexuality and marriage in a very positive way, and to recapture the beauty of human intimate relations.

This event proved that papyrus paper is still a force to be reckoned with. It also reminded me of the day I found an old piece of notepaper. In my case I’m sure the press were not interested, especially as I found it in a pair of trousers slated for the Goodwill people. It was a note to myself and I recalled just how important that message was at the time. There it was, preserved in its entirety, a reminder to pick up an antique pearl necklace. My wife still treasures the anniversary gift that it engendered, and an archaeologist going through a Goodwill midden years from now would probably have found it hard to contain his excitement at such a find.

The conservation of records at such a personal level pales in comparison to what we face in the future on a global scale. At a conference on this topic in the nineties, one speaker described “. . . the threat to all our magnetic records posed by a high altitude [over thirty kilometers] nuclear explosion, which would generate gamma radiation and erase all magnetic records within a wide area . . .” In the discussion period, someone asked who would be alive then to save our heritage. The speaker said that the atmosphere protects us, only the electromagnetic radiation gets through, and had he understood the question correctly? The person replied, ‘Yes—You’re promoting the use of paper.’”22

If that technician is correct, then it really is important to write things down. And today, the lawyers and accountants would agree. They would further caution you that once something is written down you should sign it, scan it, and send a copy to them, “and make sure you mail me the original.” Presumably on paper.

Once done, such a record is as good as carved in stone, but much more portable—a point that Moses would come to appreciate when he was commanded to appear in 1200 B.C. at God’s bidding atop Mount Sinai. Here, according to Hebrew tradition, the text of the Ten Commandments was written with the finger of God on two original stone tablets, as well as on subsequent replacements. After this, Moses was faced with task two: recording the Torah, virtually a history of the world as well as a code of ethics and behavior for his followers. Since the Torah also recounts the creation of the world and the origin of the people of Israel, their descent into Egypt, and the drafting of the Torah on Mount Sinai, it is in part or whole a significant undertaking, composed of many pages. If Moses had turned to a chisel and hammer, it may never have happened. Instead, he must have reached for a scroll of papyrus paper. Why? Because Mount Sinai was and still is located in the Sinai Peninsula near the city of Saint Catherine in Egypt, a nation in which, at that time, papyrus paper was the medium of choice. And a pen? We know that at a later date, among the Gnostic documents there is reference to God as having a pen of gold. Whether Moses was so equipped, we don’t know, or whether God loaned him His pen we are ignorant, but according to the story when he came down the mountain carrying two tablets in his arms he must have had a copy of the Torah written out on a paper scroll sequestered someplace in the folds of his robe. At this point the Bible tells us that Moses was ready to direct his people onto the path of righteousness and he never looked back. Again the same message comes through: if it’s important, write it down.

As we will see in the next chapter, Prisse d’Avennes, a Frenchman in Victorian times coming out of Egypt and, like Moses, carrying stone tablets and scrolls, items that were destined to be part of the foundations of recorded history, must have, again like Moses, reflected on the choice of medium. If papyrus paper was, after all, the dominant medium of its age, then, as Marshall McLuhan (the famous philosopher and professor of communication technology) would argue, such media shaped the way we perceive and understand our surrounding world. And this is exactly what happened, as papyrus paper went on to affect the Western world for almost four thousand years.

One school of media scholars, led by Donald Shaw at the University of North Carolina, has recently drawn attention to what they refer to as the “emerging Papyrus Society,” a society in whch there is a more personalized mix of personal messages, as in ancient times when messages were the ones more easily transportable by papyrus paper. This need of modern man for a personal, portable means of communication, is the result of a long period of evolution that started with the move away from messages painted and carved on rock faces. Once the move was made to the new medium—mobile, flexible, portable paper—it never stopped. This was a pivotal moment in world history; we had been set free. In essence, papyrus paper was the midwife at the birth of civilization and had literally cut the cord. It freed man from his dependency on writing on unwieldy surfaces. It allowed man to carry his messages and records with him as he moved around, an innovation the like of which was not seen again until the introduction of wireless technology in the twentieth century. And, once set in motion, this new media assisted in the advent of the first newspaper. In later days, newspapers, news magazines, radio, news channels, and TV programs directed the news to listeners and viewers in a vertical fashion—top-down to the entire community. These major media are fighting a losing battle with the new horizontal media: social networking, blogs, web sites, cable TV, satellite radio, etc.

All this will come as a surprise to modern Internet users who may assume that today’s social-media environment is unprecedented. But many of the ways in which we share, consume, and manipulate information, even in the Internet era, build upon habits and conventions that date back centuries. Today’s social-media users are the unwitting heirs of a rich tradition with surprisingly deep historical roots . . . social media does not merely connect us to each other today—it also links us to the past. (Tom Standage, “Writing on the Wall: Social Media—The First 2,000 Years.”)

Since attention spans are limited, people today mix and match media to a greater degree, which led Shaw to consider another dimension to the meaning of his modern day Papyrus Society. It seems that papyrus paper required two layers of papyrus pith in its manufacture: one laid horizontally and one laid vertically. To Shaw, this matrix is a physical metaphor for the challenging modern media mix of vertical power and horizontal spread. (It also can be seen, as pointed out by Shaw and his colleagues, as a balancing between the power of vertical, institutional society, represented by magnificently rising pyramids, and the ease and convenience of social media to convey information, such as papyrus paper once allowed.)

One goal of this book will be to provide a history of paper and books during the early days of antiquity. Another goal will be to present an overview of how papyrus lent itself to the task of producing these books and how, in doing so, it helped revolutionize the world.