Prisse, like Moses, Carries Home Stone Tablets and Paper Scrolls

Once Prisse d’Avennes had packed his treasures into twenty-seven large cases, he needed to carry his trophies downstream to Cairo. In the spring of that same year, 1844, on the other side of the world, the first electrical telegram was sent by Samuel Morse from Washington, DC, to a railroad depot, asking the question of questions, “What hath God wrought?” Prisse was certain the Egyptians would ask the same question once he had gone, but in reference to him: “What hath d’Avennes done?”

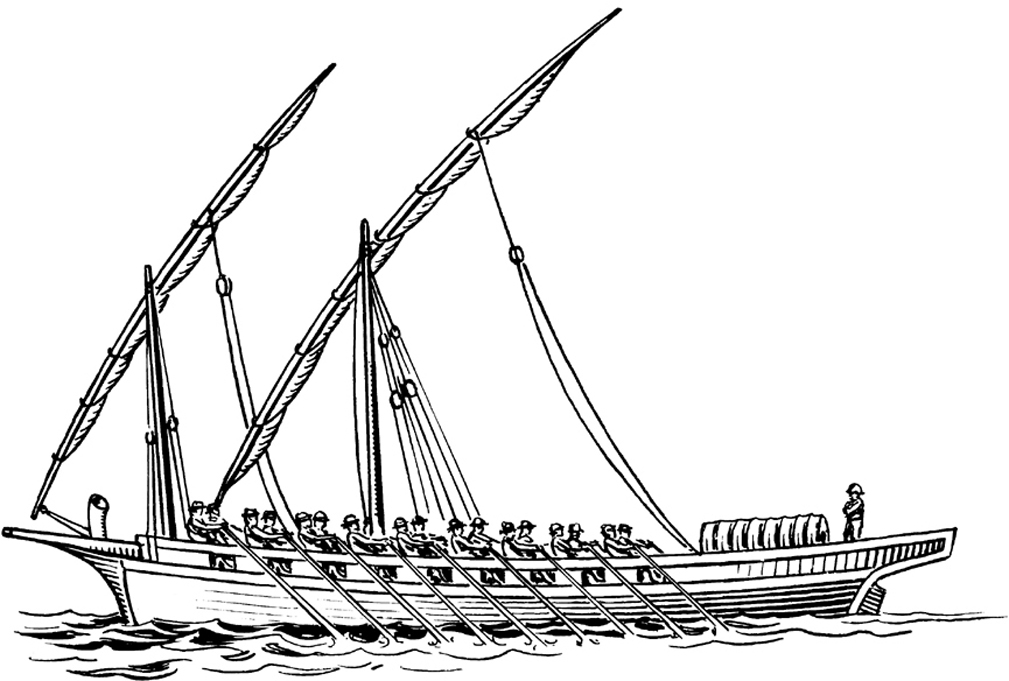

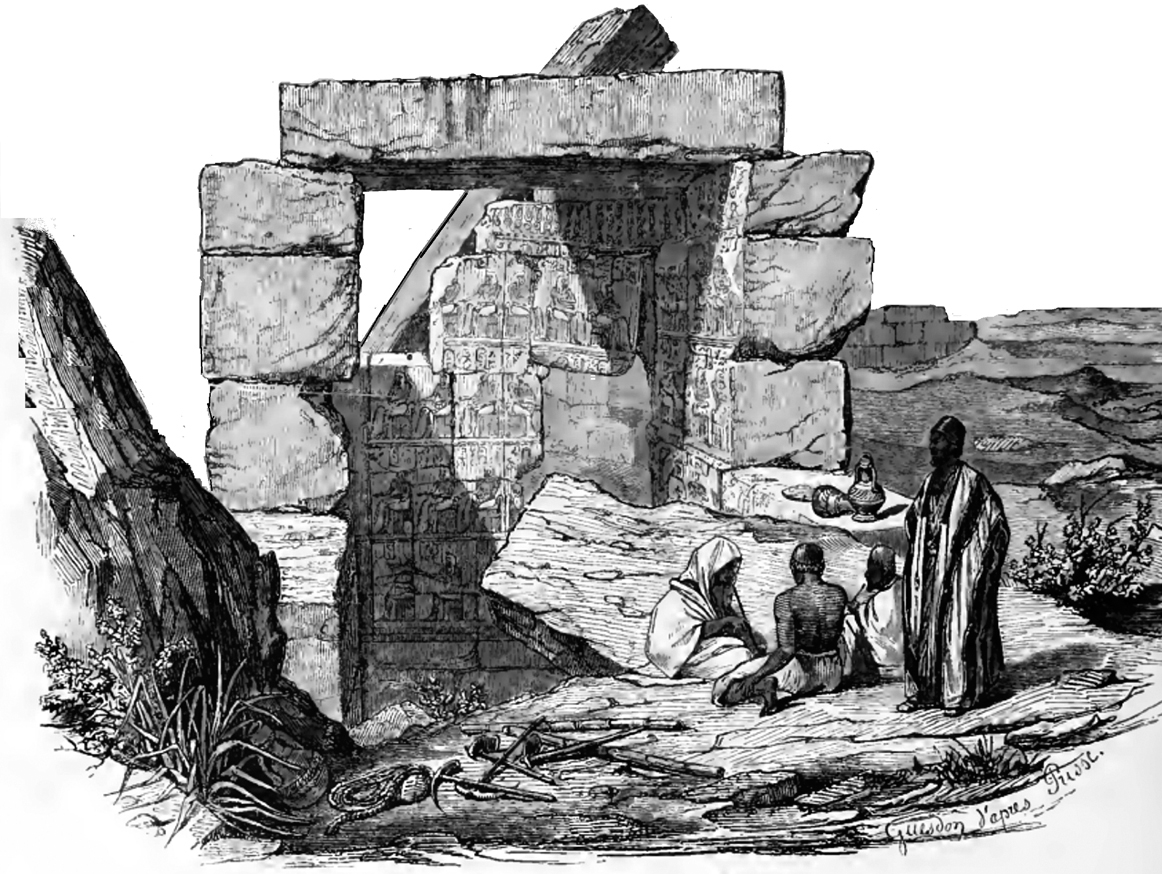

He had little time to ponder how such things as the invention of Morse would change his world, which was still a paper world. His small crew had been working every night for almost a year, secretly cutting over sixty sculptured panels from the Amun temple in Karnak near the port town of Luxor, formerly Thebes (Map 1). Having done this without a permit (firman) or diplomatic immunity, he stopped work in 1844 when he found out that the local governor of the Quena region had been tipped off about what he and his team had been doing.1 The minute his tent had been placed under government watch, Prisse decided it was too risky to stay; it really was time to get out while he could. By noon the next day he had rented and loaded a large felucca boat. That night, as the moon rose over the river Nile, he made his escape.

Falucca on the Nile with crew in the 1840’s (Wikipedia).

As they pushed off from the pier, the captain of the felucca took the tiller and several of his crew rowed while Prisse and his workmen lay down on the deck for a well-deserved rest. The river current and the rowers carried them steadily away from shore and out into the main stream.

Prisse d’Avennes was perhaps the most skillful treasure hunter to ever come to Egypt. Strangest of all was the fact that he hadn’t intended it that way. When he first arrived in 1826 at the age of nineteen, he carried with him a diploma in drafting and engineering from a respected French school and a pedigree—he came from the French branch of a family descended from the English noble family of Price of Aven. His parents and grandparents were prominent administrators and lawyers and he was intent on assisting the viceroy, Mohammed Ali Pasha, and his son, Ibrahim Pasha, with engineering and water development projects. In the process, and over the course of many years, he acquired a proficiency in Arabic, Turkish, Greek, Coptic, Amharic, Latin, English, Italian, and Spanish. He also taught topography and fortifications in Egyptian military academies, traveled widely in the East and, after taking the name Edris-Effendi, embraced Islam.

Though contentious by nature and in the habit of alienating his colleagues, he succored the sick and poor and remained a model of deportment. He was never thought of as a man who would steal, and he disparaged those who did. He is famously quoted as saying, “. . . learned society has now descended like an invasion of barbarians to carry off what little remains of its [Egypt’s] admirable monuments . . .” If anyone could claim the moral high ground, it was this man.

Émile Prisse d’Avennes 1807–1879, French archaeologist, architect. (Wikipedia).

What happened? What changed his character so? Why on that night in 1844 was he lying down on a felucca with a band of rogue workmen, a group no better than a gang of thieves, in an escapade that was entirely against local law? He knew he had committed a crime, one of serious proportions, but he had been driven to it by his bosses, the Pashas. They made it known throughout Europe that they would trade antiquities, including obelisks, ancient tombs, and any and all pharaonic treasures for cotton gins, steam engines, mechanical looms, metal works, and sugar mills. They encouraged the leveling and recycling of all ancient monuments in their haste to rebuild Egypt as a modern country. When Prisse learned that they planned to demolish the Temple of Amun in Luxor, he acted. He became a man who would steal for a cause, not for gain.

Prisse’s men removing the stone panels in Karnak, 1843 (Wikipedia).

Through superhuman exertions and with virtually no resources, save a few men and fewer tools, and working mainly under cover of darkness, Prisse removed the carved stone blocks from the temple walls that included the figures, cartouches, hieroglyphic signs, and details of all known Egyptian kings. Known as the Karnak King List, this incomparable record included the details of over five-dozen royal predecessors, ranked in dynastic order. The writer Mary Norton tells us that he also succeeded in extracting several tablets (stelae)—one with domestic scenes dating from 4000 B.C.,2—and a papyrus scroll that turned out to be as important as all his other loot. Discovered in Thebes, Prisse bought that scroll from one of the fellahîn whom he employed when he was excavating at the necropolis there. It has since been dated to 1800 B.C. and refers back to the nobility of Khufu’s time. Known as the Prisse Papyrus, it is said to be the oldest literary work on paper in the world.

When he neared Cairo, he tied up his felucca in Boulac, the nearby Nile river port, and left his foreman in charge of the boat and its cargo. He sought out the French vice-consul and implored him to place his precious cargo under diplomatic protection, but the official refused. Undeterred, Prisse returned to his boat. Along the way he met the famous archaeologist and scholar, Richard Lepsius, leader of a Prussian team that had just started assembling an expedition that would travel up the Nile. Sanctioned by the Pasha, Lepsius would later come away with his own impressive collection, including a dynamited column from the ill-fated tomb of Seti I, and sections of tiled wall from Pharaoh Djoser’s Step Pyramid at Saqqara. All of these were official presents from Mohammed Ali Pasha in thanks for a dinner service presented to him by Lepsius in the name of the Prussian king. Prisse invited Lepsius back to his boat and entertained him that night with coffee while the famous man sat on one of the cases, not knowing what was in it.

In May 1844, a full year after he had first sunk his chisel into the monumental walls of the Temple of Amun, Prisse sailed downriver to Afteh. If he had waited another twenty-five years, perhaps it would have been easier to get away, since by 1869 the Suez Canal would be in place. Instead, Prisse had to transit the Mahmoudieh Canal, which connected the Nile to the sea at Alexandria and delivered fresh drinking water and food to that city. The canal had been dug by the Pasha, Prisse’s old boss, at a loss of 15,000 men. Prisse had his felucca towed in tandem with a barge and steam tug up the canal to the port of Alexandria where he unloaded his crates and boarded the French steamboat Le Cerbère that called at Malta and Gibraltar en route to Marseille.3

So, after many years of dedicated work in Egypt, he left for France and glory. On arrival, he presented the stone tablets that comprised the Karnak King List to the Louvre and was awarded the Legion d’Honneur in 1845. What then was the outcome of Prisse’s efforts? His King List had simply joined a host of others.

There have been many other king lists discovered since his time, including the Palermo Stone carved on an olivine-basalt slab and broken into pieces and acquired by F. Guidano in 1859 (it is kept in Palermo); the Giza King List painted on gypsum and cedar wood, taken in 1904 by George Reisner from a mastaba at Giza (it now rests in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston); the South Saqqara Stone carved on a black basalt slab that was discovered in Saqqara in 1932 by Gustave Jéquier; the Abydos King List of Seti I carved on limestone that is still in place on the wall of the Mortuary Temple of Seti at Abydos in Egypt; the Abydos King List of Ramses II carved on limestone, dug up in Abydos by William Bankes in 1818 (now in the British Museum); and the Saqqara King List carved on limestone and found in 1861 in Saqqara (now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo).

Surprisingly, the most reliable kings list in history for the chronology of the period prior to the reign of Ramesses II (1200 B.C.) wasn’t even cut in stone, but written out on papyrus paper. It is called the Turin King List. Inscribed with red and black ink, it was acquired by the famous collector, Drovetti in 1820 at Luxor. Even though it is damaged, it includes all the early kings of Egypt up through at least the Nineteenth Dynasty. Kept in the Museo Egizio in Turin, it is yet another excellent example of the advantage of copying out messages from stone to paper. In this case, a papyrus scroll has trumped many of the previous carved or painted monumental artifacts.

The second remarkable thing is that, with the exception of the two Saqqara lists and the Abydos Seti list, all of the above were discovered by Victorian and Edwardian collectors and are now kept outside of Egypt. Should they be repatriated, especially if they were illegally exported? These are questions that have been argued for years, but there is less talk today of repatriation to Egypt since the Arab Spring revolutions of 2011. After the fire-bombing of the Egyptian Scientific Institute near Tahrir Square in Cairo in December 2011, volunteers spent days trying to salvage what was left of the 200,000 historic books, priceless journals, and extraordinary writings kept in the institute. This presents a conundrum, should people acquire by any means (including illegal transactions) in order to “rescue history?” or should they demand the return of hundreds of thousands of objects from around the world? Any massive repatriation would overwhelm the curators and resources of the museums in Egypt, making the situation worse.

Perhaps the solution lies in what seems like a general philosophy offered by Salima Ikram, the well-known archaeologist and professor of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo. After advising that, without question, certain items should be returned to Egypt, she pointed out that many items on display overseas “are the best ambassadors that Egypt has.”4 She wondered what would happen if everything went back to Egypt. A mass repatriation would leave a vacuum in the world. “How will anyone know about Egypt? How will anyone be excited?” The impasse has not been resolved despite the impending opening of the long-planned Grand Egyptian Museum at Giza, which could harken a return of the many Egyptian antiquities in museums around the world, should the organizations that currently have these artifacts prove willing to return them. As a consequence, for now, many of these kings lists will probably remain where they are.

The diary and spreadsheets of Merer are the tip of an iceberg when it comes to pinpointing when the use of paper first exploded into the mainstream. We have some idea of how extensive paper use had become in ancient days when a host of ancient fragments and scrolls were uncovered by nineteenth century collectors and archaeologists. Included among these nineteenth century discoveries is an assortment of business papers relating to the cults of an ancient royal family, the Abusir Papyri from the Old Kingdom (about 2686–2181 B.C.), and a scattered array of literary papyri including the Westcar Papyri (1800–1650 B.C.) that contains five stories about miracles performed by priests and magicians (these tales were told at the royal court of Pharaoh Khufu by his sons).

When the Prisse Papyrus was handed over to the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris in 1845, it was divided and glazed and has been on exhibit for 170 years. Spread out flat, it measured about twenty feet, seven inches, with an average height of about 6 inches. It contains eighteen pages of bold, black and red hieratic script that is said to be the earliest literary use of papyrus paper. The papyrus relates “The Maxims of Ptahhotep,” itself a copy of a work written by the Grand Vizier Ptahhotep, during the reign of Djedkare Isesi (2475–2455 B.C.). The maxims are directed to Ptahhotep’s son. The scroll also contains lessons and advice from another vizier, Kagemni, who served during the earlier reign of Pharaoh Sneferu (2600 B.C.), father of Khufu.

Leila Avrin, author of Scribes, Script, and Books, believed that “The Maxims of Ptahhotep” began an age of classical literature in Egypt that blossomed during the Middle Kingdom, a new wave of middle-class ancient literature that sprang up as writers became aware of social evils and the use of the short story as a genre. Among ancient Egyptian texts, which fall in this class and surfaced over the years, we find The Eloquent Peasant, The Dispute Between a Man and his Ba, and The Story of Sinuhe. There is also Teaching of King Merikare, a literary composition taken from three fragmentary papyri produced in 1540–1300 B.C.

Along with these is the classic papyrus containing The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor, a story told of an ancient voyage to a king’s mines (2000–1650 B.C.). Considered to be the oldest fantasy text ever written, it involves a hero who sets out on a sea journey, encounters a storm, lands on an enchanted island, and battles a monster that turns out to be the prototype for the greatest imaginary monster of all time—the dragon.

Mathematical and medical papyri dating back to 2400–1300 B.C. were also recovered by collectors and archaeologists. All of which indicates that from 2500 B.C., countless scribes, priests, and accountants made a living using papyrus paper that was by then a common enough item, which served them well. Then, at the beginning of the New Kingdom, around 1550 B.C., another type of scroll began showing up, this time in tombs and coffins. A copy of a Book of the Dead, a guide to the correct path to eternity, was prepared and treated in much the same manner as the mummy they were associated with; consequently, a significant number have survived whole or in part.

More correctly known as the Book of Coming Forth by Day, it contained those magic spells needed to assist the soul on arrival in the afterlife. People who commissioned their own copies chose spells they thought most vital, which must have been a gut-wrenching process. Which spells to choose? Would they get it right? Their whole future in the afterlife depended on their choices, and on the availability of paper.