Papyrus Paper, Your Ticket to Paradise

Papyrus paper opened up a new path to immortality by allowing common people in ancient Egypt to possess their own copy of the Book of the Dead, Anyone who wanted it, and could afford it, could be guided directly to paradise by their papyrus scroll while paddling in their personal papyrus canoe (A small model of a boat left in your tomb served just as well, since it could be converted in the afterlife by magic into the real thing). Once they arrived in paradise and began life anew, they found themselves in the Field of Reeds. Perhaps unspoken in all of this was the fact that this Field of Reeds really did exist at some earlier time, like the Garden of Eden, which is said to have existed in the region of the Tigris-Euphrates River valley within the Fertile Crescent. The Field of Reeds pictured and described in the Egyptian papyrus scrolls may have reflected an earlier time in history when a fertile, green, tropical heaven existed on earth, for which there is now proof. It is known generally as the Green Sahara.

The paleoecology of this region (see insert, Map A) was outlined in a National Academy of Sciences review in 2010, which revealed the astonishing fact that a water world existed in this part of Africa from 8000 B.C. up until about 3000 B.C. An extraordinary region, consisting of the whole of the Sahara, it was interlaced with large, interlinked waterways made up of thousands of rivers, and several lakes, each larger than Belgium.1 The terrestrial vegetation in the region consisted of savannas interspersed with tree species.2 A sequence of alluvial fans (fan-shaped deposits of sediment) existed west of the Nile Basin (see insert, Map A) that could well have once been a series of inland deltas, similar to the Okavango Swamps of Botswana. If that were so, they would most likely have been dominated by papyrus, like the Okavango swamps are today. In total, the individual swamps of the Green Sahara would have made up an enormous aquatic ecosystem, ten times as large as the Nile delta—which until modern times was itself a formidable wetland with papyrus much in evidence.

A rough estimate would put this prehistoric wetland at about 12 million acres. A description of it passed down by oral tradition from prehistoric people to the later ancient Egyptians could easily account for the concept of a “Field of Reeds.” That it lay coincidentally in the west where the sun died every day and which was the preferred resting place of the dead was all to the good.

The Green Sahara resolved the long-standing mystery of how early man, fish, and other animals moved into, around, and across the Sahara. This lush country was not only a paradise for aquatic animal species—such as tilapia fish, crocodiles and hippos—it was also a haven for papyrus and papyrus swamps, which would have grown in abundance throughout the many aquatic habitats, especially along the rivers that cut their way through the savannas. In fact, papyrus is thought to have played a major role in the diet of one of the early human species, Australopithecus boisei, who lived in Africa from 1.2 to 2.3 million years ago. If so, he would have had to eat up to two kilograms of papyrus each day to get by nutritionally. 3

In later times (after 3000 B.C.), arid conditions set in. But even then, although the verdant countryside had turned to desert, there is plenty of archaeological evidence dating back to the Old Kingdom that indicates Egyptian movement through the desert region. Though restricted to caravan routes, such as the Abu Ballas Trail (see insert, Map A), travelers from the time of Khufu until that of the Romans could make their way west. Once reaching Gilf Kebir (in the far southwest of present-day Egypt) they were allowed a choice. From there they could travel in several directions, including southwest toward Lake Chad.4

In the time of Khufu, travel was not easily done along this trail, since water was required at every step and had to be carried, but in the days of the Green Sahara, during the height of the Stone Age. 6,000 B.C., when water was everywhere, expeditions must have been easier. Once in the ancient land of Chad, any members of an expedition would presumably want to explore, or even settle in. The naturalist Sylvia Sikes brought a sailboat to Lake Chad in 1969 in order to survey it,5 why couldn’t the Egyptians have done the same thing in 6000 B.C.?

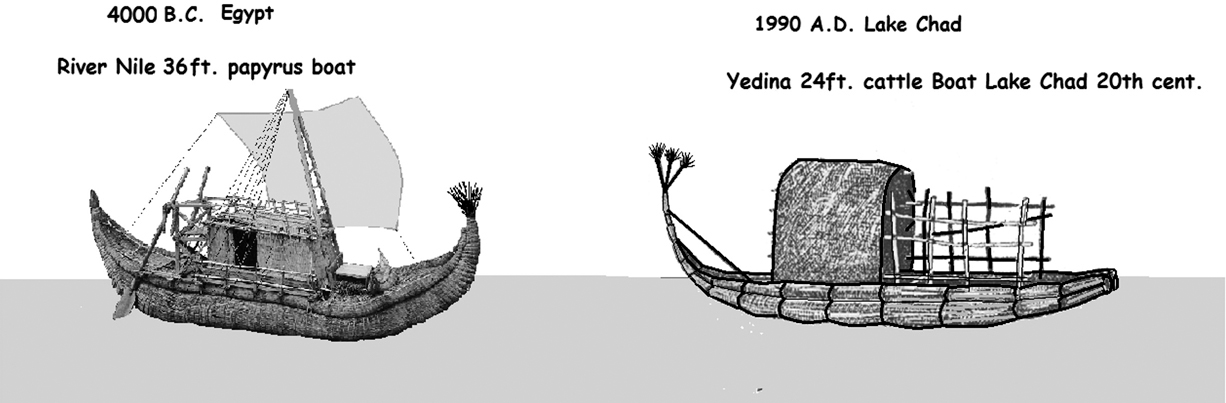

An ocean-going papyrus boat based on ancient lines compared to a modern day cattle boat both built from papyrus from lake Chad (after Konrad 1957 and Wikipedia).

In those days water was plentiful and since papyrus would be growing in profusion on, in, and along the major lakes and watercourses, Egyptian visitors to Chad or local residents could easily have assembled a fleet of papyrus boats, each craft constructed almost entirely from local papyrus. The rope used in the rigging and in the construction of the boat was readily made from dry papyrus stems as was a hull.6 Even sails could be woven from the flexible skins of green papyrus stems. The only thing that couldn’t be made from local papyrus was the mast and the stone anchor, which meant that, since papyrus grew there in quantity, any such expedition would have to bring nothing with them except some very sharp flint knives.

In 2003 the desert explorer, Carlo Bergmann, discovered carved drawings of papyrus boats on rock faces in the region. Dating probably from Khufu’s time, they may represent a notion of what went on in earlier days.7 Of course, in the Green Sahara grasslands also prevailed interspersed between the wetlands. Woodlands were common especially in the south, why not use trees to construct wooden boats? It would have been possible, but the Egyptians only started building wooden boats in the Old and Middle Kingdom (2900–1650 B.C.). During that time in Egypt, wooden ships were being built at a shipyard on the Nile in Koptos, north of Thebes, and then disassembled for transport across the Eastern Desert, where they were reassembled for use in trading on the Red Sea.8 Wooden riverboats like the famous Abydos boat (75 feet, 2900 B.C.) and the Khufu boat (143 by 20 feet, 2500 B.C.) would not be practical for Lake Chad, as they were slim craft designed to be disassembled for transport around the Nile cataracts and other obstacles. They were built for use in calm water, not for the rough water that could build up on the enormous Lake Chad, which in ancient times was equivalent in size to the Caspian Sea. The first large wave would have shattered a riverboat hull and ended any exploration from the start.

In 600 B.C. the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho dispatched a Phoenician fleet of wooden boats to circumnavigate Africa. But all that was much later. In the time of the Green Sahara in about 8000–5000 B.C., it was possible to use log dugouts in shallow water but wooden boat technology was not yet there and papyrus boats would have to do for travel on the open lakes.

On the other hand, papyrus boats, as Thor Heyerdahl proved so conclusively in 1969, ride well above the waves and will not sink until they waterlog after several months. He found that his Ra I, a forty-five-foot, twelve-ton replica of an ancient papyrus boat, carrying five tons of superstructure and cargo, as well as seven crew members, rode high on the water and sailed easily before the wind. If beached and dried occasionally, such papyrus boats should last for years.

By a quirk of fate, the reverse process occurred in 1969 when Heyerdahl, desperate for papyrus boat builders, encouraged two boatwrights to come to Cairo from Lake Chad to build the Ra I. There were no papyrus boat builders left in Egypt; they had vanished with the sacred sedge. Thankfully, papyrus boats were still produced on Lake Tana in the upper region of the Nile, and in Lake Chad where there were hundreds of papyrus boat builders living around the lake.

After 3500 B.C. the climate changed, and the Sahara dried out. The extinction of mammals during this period has been reviewed in a paper from NASA in 2014 that tells of the collapse of the whole ecological network (12,800–3500 B.C.)9 After this point, the desert became the barrier to movement that it is now. And incredibly, this whole story may have been recorded on papyrus paper.

Most likely the rise in use of funerary documents among common people, facilitated by papyrus paper, did not go unnoticed by the Egyptian royals. I would think they must have been appalled when they saw the Book of the Dead pass from exclusive use by kings and viziers to courtiers, officers, civil servants, and finally to the general public. Taylor tells us that it became the most popular funerary text in the kingdom. Perhaps viewing this as a trivialization of a sacred text and a loss of prestige, Pharaoh and his viziers had the priests carry out even more advanced and detailed research on the next world, so that by the New Kingdom (1079–712 B.C.) the royals had gained special knowledge, which they then incorporated into a new set of texts known as the Amduat.

During the New Kingdom, the Amduat was joined by other funerary texts including the Book of Caverns, Book of Gates, Book of the Earth, Book of the Heavenly Cow, Books of the Sky, Book of the Netherworld, and Book of Traversing Eternity. Of all these, the Amduat (literally, “What is in the netherworld?”) remained the oldest and most important of these books.10

At first the Amduat’s use was restricted, appearing primarily on the walls of tombs of kings and viziers; then from 1069–945 B.C., it ceased to be a purely royal prerogative and, like the Book of the Dead (in use from 1550 B.C. to 50 B.C.), it became more widely available. During this time and later, around 945–850 B.C., versions of it were written and drawn on papyrus rolls which were placed along with a shortened version of the Book of the Dead in the tombs of high officials, priests, and their wives.

The Amduat differed from the Book of the Dead in that it described and illustrated the course the sun takes while illuminating the Duat, or world of the dead, during the twelve hours of night. The fascinating thing, according to Thomas Schneider, professor of Egyptology at the University of British Columbia, is that the journey of Ra described in the first three hours of the Amduat is similar to the trip one would have taken from Egypt to Lake Chad in the days of the Green Sahara.11

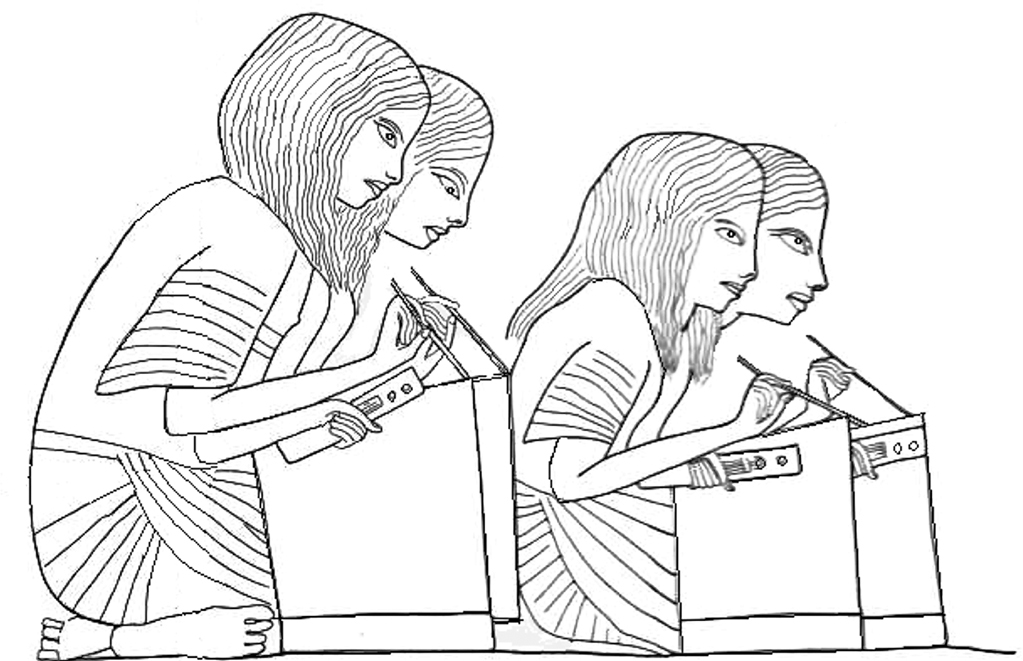

He describes a correspondence between the journeys: in that during the First Hour, Ra travels west with the deceased royal personage, toward the sunset in papyrus boats similar to those found in modern Chad and ancient Egypt. They gain access to the underworld through the “western portico of the horizon,” a passageway of 738 miles (1260 kilometers in converted units in the text) from the Nile. During the Second Hour, Ra and the deceased enter “the watery expanse of Ra,” a region dominated by a gigantic sweet-water ocean. The text also mentions green plants, animals, and the surrounding lands; in the Third Hour they encounter the “waterway of Osiris,” which also involves a large water body. Professor Schneider found that in their description of the Amduat the ancient Egyptians made detailed references to the vast array of rivers and lakes to the west across the Sahara. It matched the paleo-environment as well as the topographical features of this realm.

The goal of this nighttime journey was to reach the hidden realms of the cosmos, which were characterized by floodwaters and green fields, a landscape evocative of creation and of the Field of Reeds found in the Book of the Dead. But in the Fourth Hour of the Amduat, Ra, and the deceased pharaoh who travels with him, reach the sandy realm of Sokar, falcon god of the Memphite necropolis at Saqqara.

In the Book of the Dead, the Field of Reeds, called Saket A’aru, is described as boundless reed fields, like those of a prehistoric earthly Nile delta. The diagram describing the Field of Reeds first appeared on some coffins in the Middle Kingdom (2050 B.C.–1710 B.C.) and according to Taylor is the only true depiction of a landscape in the entire Book. The Field of Reeds shown in this diagram is usually placed in the east, where the sun rises.12 This ideal hunting and farming ground allowed the souls there to live for eternity.13 In the Amduat we see the story of Ra traversing the watery expanse of the west (referred to as Wernes). The two books were considered complementary and in both cases we see the ancient Egyptian’s fascination with all things wet, especially the lush, floodplains as they existed in the ancient water world of the Nile valley.

Papyrus was the medium in this instance, as well as the message, and, as in the case of papyrus boats and paper scrolls and books, the message could be interpreted either as the word of God, Osiris, or Christ, or it could be seen as an account of how people could travel and trade ideas. Diffusion was possible using the Egyptian and Chadian solution which was to use the local vegetation to build a sail boat or make a book or scroll, either would see you to your destination on earth or in heaven.

Once early Egyptians settled in the Nile River valley, they left behind the arid land of the Sahara, abandoning it to the desert people. In the process, they also left behind a number of cultural parallels. The writer and former Peace Corps volunteer on Lake Chad, Guy Immega found this was especially true in the areas of language, music, musical instruments, cattle, fish and fishing, the use of papyrus, and the waterman’s life style.14 Papyrus-boat building was an obvious carryover, but there may also have been a large influence in the way the local people, the Yedina (“people of the reeds”) built their papyrus houses. That seems to be a throwback to the way Egyptians might have built their own huts when they were living in their own water world in 8000–3000 B.C. in Egypt.15

On the other hand, it could all be just the reverse. Maybe the ancient Yedina taught archaic Egyptian settlers all about life in and near the water. Maybe they helped them to get started in making use of the swamps that grew so luxuriantly around as well as in Lake Chad, and as well along the Nile, or even showed them how to make papyrus paper. If so, we may owe a great debt to the Yedina, or their predecessors the Sao, for helping at the birth of Western civilization.

In any event, the Book of the Dead is key in helping us understand the way the ancient Egyptians saw the world, and how the paper that they invented could serve as an ideal medium on which to record the thoughts of mankind. It also represents a key moment in the democratization of knowledge, something that could not have happened without the inherent advantages of paper—it was flexible, easy to obtain, and cost-effective. As a medium for the Book of the Dead and recording the history of the ancient world of the Green Sahara, it was perfect. You could use colored inks applied by brush or pen; it could be cut, pasted, folded and sealed; nonpermanent ink could be erased and easily corrected; whereas permanent ink though it couldn’t be erased, could be “whited out”; and the needful or thrifty could recycle sheets and scrolls and use them again and again. As a last resort it could be softened and used like papier-mâché to model and form a whole range of objects including a rishi coffin or a mummy case.

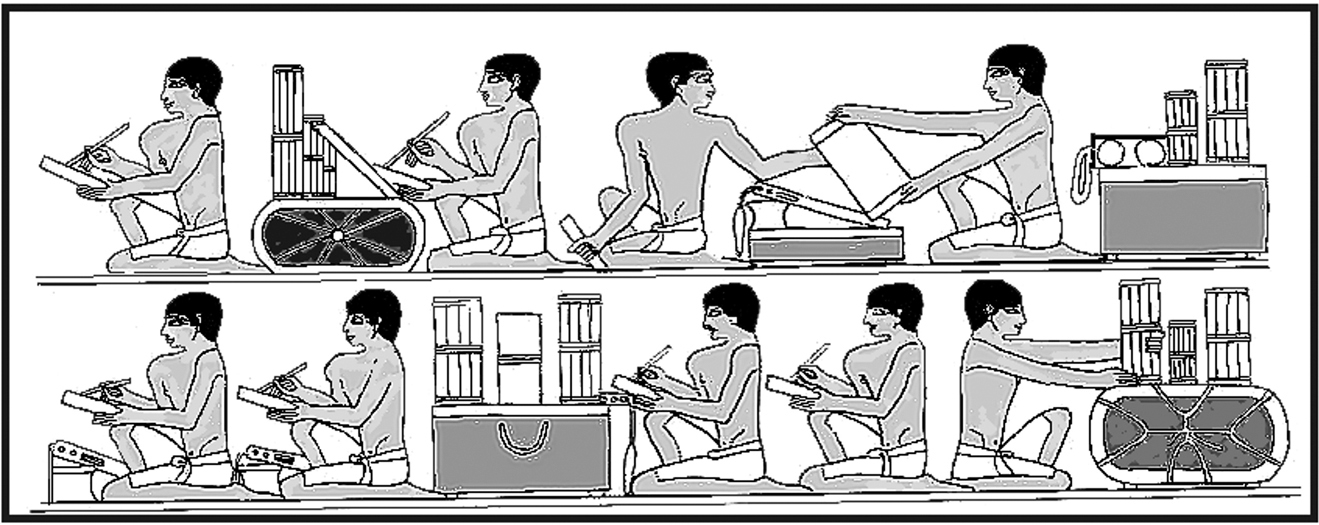

Above all, paper lent itself to the new form of writing. The old pictorial form using glyphs had given way to a cursive form of handwriting mostly because it was easy to write this way on paper, and faster, too, to keep up with the exploding demand for paper text.

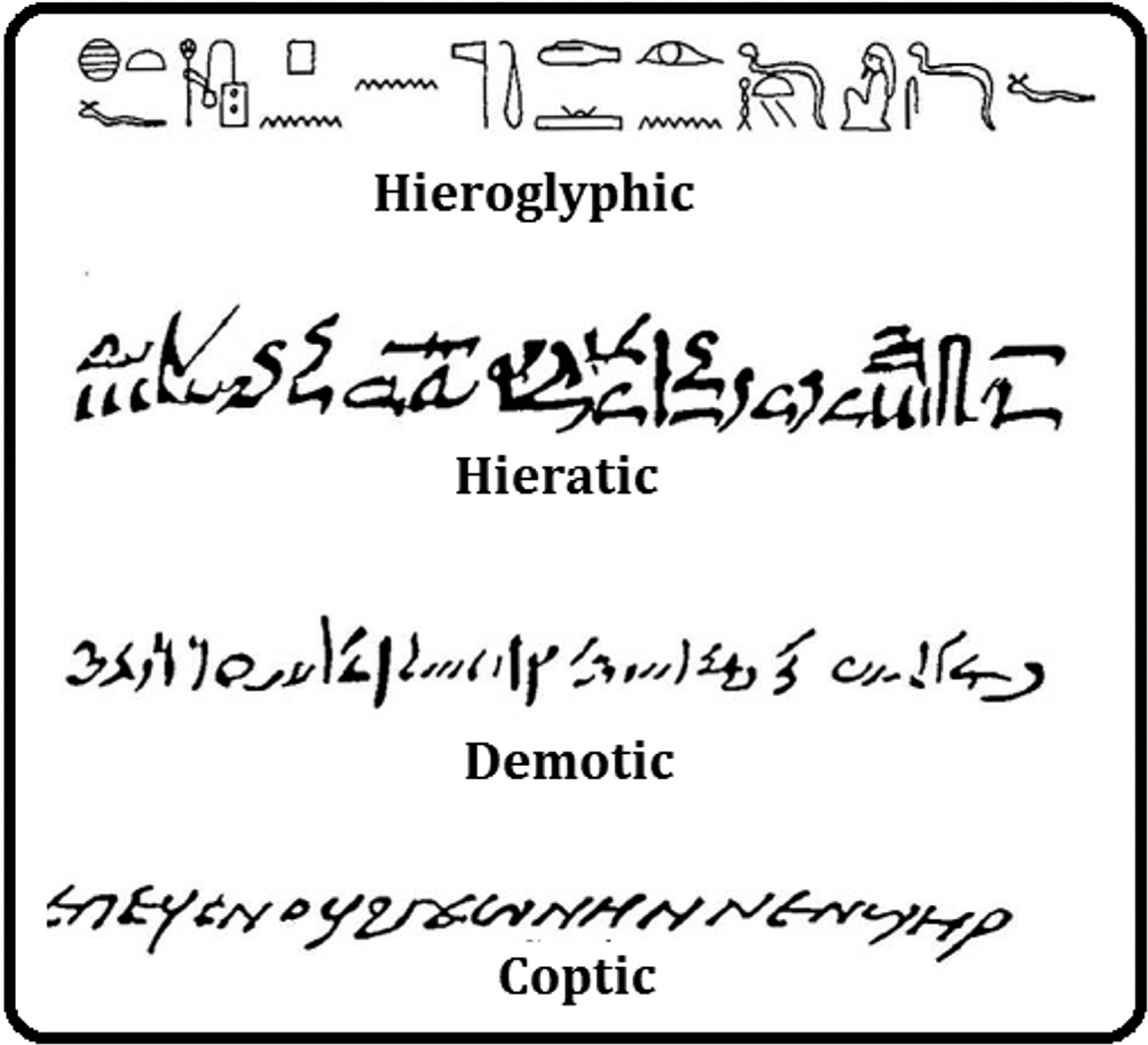

The Egyptians employed four different scripts for their one writing system. The earliest was hieroglyphics, which was read from right or left depending on which way the characters faced. The second script, hieratic, was cursive, meaning that it flowed freely with some characters joined, similar to cursive handwriting of today. It developed almost at the same time as hieroglyphic writing, but it was much faster to write. Unlike time-consuming glyphs, the streamlined characters could also be joined by strokes known as “ligatures.” Written from right to left, it remained Egypt’s everyday script until about 700 B.C. when a new form of shorthand developed in the south.16 Promoted by the business world this third script became so prevalent that Herodotus called it by the Greek word for “popular,” demotikos. As with hieratic, this script was written from right to left.17 Called demotic, it was an Egyptian cursive that had by now become so changed that there was little similarity to classic hieroglyphics. It lasted until it was replaced by Coptic, a script that dated from the time of Alexander’s conquest of Egypt in 332 B.C. This was the Greek version of all three previous scripts: it made use of Greek letters and included vowels.

Four scripts compared (after Linkedin Slideshare.net).

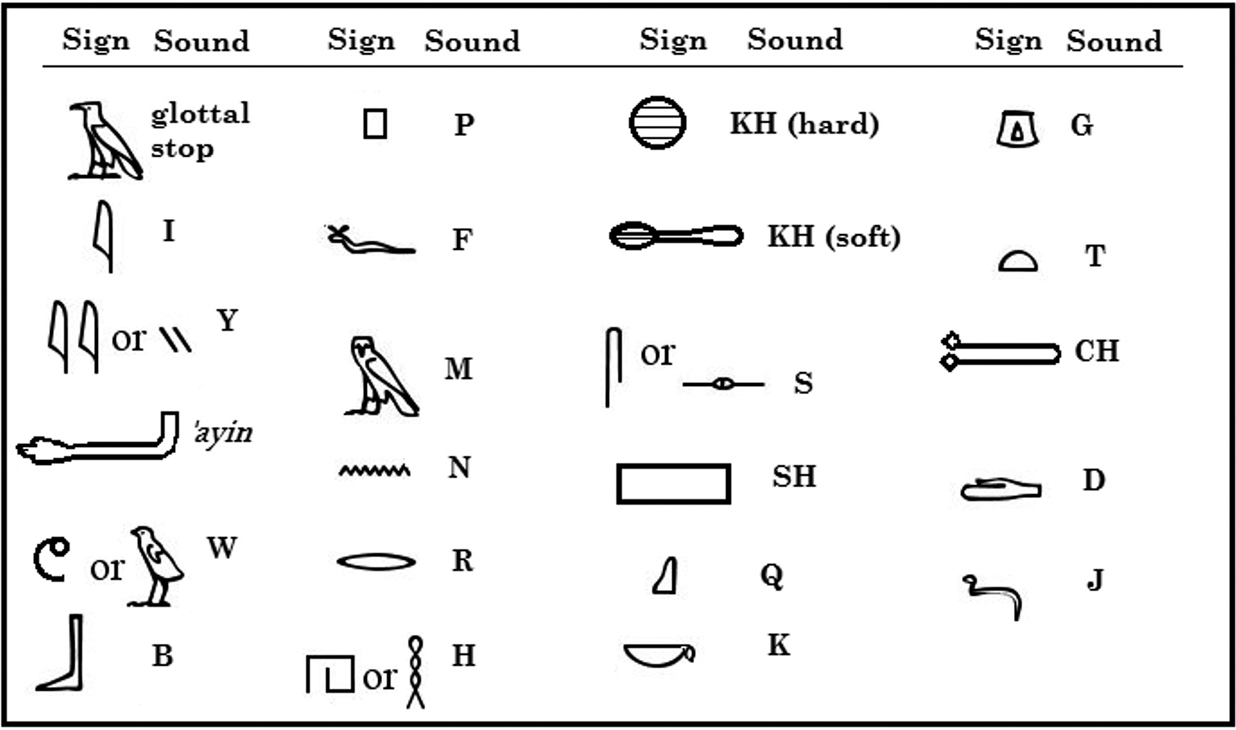

Old form of the hieroglyphic alphabet (after Fischer, 2001).

In appearance, all four scripts were different, but in form, function, and usage they were still just one writing system, which had begun in the earliest days when Mesopotamia’s phonetic writing had reached the Nile. Hieroglyphs were born when Egyptian scribes converted the Mesopotamian idea into something unique, a new system that used hundreds of signs. Of these, the most common was a set of twenty-six that represented mostly consonants. Today we know this as the hieroglyphic alphabet,” commonly found on the Internet and used by jewelers to trace your name in “Egyptian” on bracelets and necklaces. Though it still lacked most vowels, the hieroglyphic alphabet was a remarkable innovation; it was the first of its kind, and it supplied the forms that were taken for the later alphabets of 2200 B.C., which led to the various Semitic alphabets that became the Latin alphabet we use today.18

Stephen Fischer, writer and expert on ancient languages, summarized the process of the development of the alphabet when he noted that writing as we know it may have originated with the Sumerians, but “the way we write and even some of the signs, which we call ‘letters,’ are the ultimate descendants of ancient Egyptian . . .” According to Fischer, the Proto-Sinaitic script (1850 B.C.) shows at least twenty-three discrete signs—almost half of them clearly borrowed from Egyptian. For example, the depicted object “waves in water,”—n in the Egyptian alphabet—became m, which reproduced the initial consonant of the Semitic letter mayim. Our Latin alphabet’s m is a direct descendant, still “showing the waves.” 19

Years later in the New Kingdom, the use of hieratic script was confined to documents of value and religious texts, while demotic, the even more cursive form, was regarded by the Ptolemies, the royal Macedonian Greek family that ruled Egypt from 305 to 30 B.C., as some sort of quaint, old-fashioned form of writing. They referred to it as “enchorial” or “native” writing, a reflection of their Greek heritage; they saw Greek in the same way that many today look upon English as the only sensible language for discourse. Little did they realize that in demotic they were looking at the end of a very long cycle where the Greek written language, of which they were enamored, was in fact Egyptian in a modern form. It happened that in another part of the world in Greece during the ninth century B.C., as explained by Johnson, the Greeks took over the Phoenician alphabet, reversed the direction of writing, and changed some signs to vowels in order to produce the ultimate source of the Western alphabet. Since the Phoenicians had borrowed their signs from the Canaanites who had taken theirs from the Egyptians, we come full circle.

“Neither Greeks nor Phoenicians ‘created’ the alphabet,” says Fischer. “Egyptians distilled the alphabet from their hieroglyphic system.” And, as he noted further, “It is no coincidence that our method of writing at the beginning of the 3rd Millennium A.D. is not too different from that of the Egyptian scribes of the 3rd Millennium B.C.”20

To my mind, the other extraordinary thing is that in 3000 B.C. and 1000 A.D. handwriting was still being done on papyrus paper, which was still the only easily available medium around.

The complete Western alphabet, that is, one that treats consonants and vowels with equal weight, such as was used in Greek or Latin, now appears to be replacing most other writing systems of the world. Fischer views this as one of the most conspicuous manifestations of globalization. In other parts of the world, the Chinese were developing their own writing, likewise a system that would influence much of the world around them. The earliest Chinese inscriptions from 1400 B.C. displayed a characteristic writing in columns, which made it convenient for writing on dry bones as well as on narrow, yellow-colored strips of bamboo. Thus, while the Egyptians were writing a streamlined script on a light, highly portable medium, the Chinese were carefully inscribing bamboo slips that were then sewn and tied into bulky racks and rolls.

In Egypt the fast form of writing was a godsend to businessmen, accountants, and record keepers who now demanded reams and reams of papyrus paper. Soon letter writers took up papyrus paper and authors and poets matched it to their métier as Egyptian civilization advanced. By the first and second centuries A.D. the funerary document of choice had also been streamlined; it was the more condensed Book of Breathing. Its content was short, less than ten lines of the bare essentials, and written in the more fashionable demotic script. These folded, tied, and sealed missals simply listed funerary wishes that encapsulated the bare essentials.21 These were the last in the long line of evolution of the Book of the Dead. Papyrus paper was put to work in the third and fourth centuries A.D. to serve a world that was rapidly turning toward Christian practices.