The Birth of Memphis and Paper

Until now our story has dealt with dry regions, places where the first paper would have been preserved, where history was made, and where there was evidence of the great things to which the first paper was destined. We will now turn our attention to the actual production of this first paper.

This takes us from the driest areas to the wettest, since the plant that was used to produce the paper is a swamp plant. Papyrus depends on water to reach its great height (the stems grow up to fifteen feet on average) and is an integral part of delta ecosystems. So we must leave Pharaoh Khufu in Giza and Chancellor Hemaka in Saqqara—both dry places on the western edge of the Nile valley bordering the desert (see insert, Map B)—which makes sense, as both are burial sites where stone mausoleums, pyramids, and deep, dry tombs make preservation possible and provide an ideal base for life in the next world.

Memphis today. View from the ruins toward modern day Mit Rahina (Wikipedia).

The wetlands in which papyrus grew were a world apart. Backwaters and swamps were found all along the floodplain and into the delta, and consisted of all the areas connected by water when the countryside was flooded for months on end every year. Even after the flood subsided, water remained, trapped in pockets and basins. Living in such regions was only possible with water control. Because Memphis was made of mud brick, wood, and reed buildings—stone being reserved for monuments and temples—most of the city would have washed away during inundations were it not for drainage installed early in the life of the metropolis. Drainage was something the Egyptians were extremely good at.

In later years, when hard times fell on Memphis, the dykes and drains fell into disarray, and “Its temples fell prey to vandalism and quarrying. What survived is nowadays buried under a thick layer of Nile clay and covered with modern houses and fields. So today, most of Memphis is lost.”1 The passing of the pharaonic civilization, the rise of Ptolemaic Alexandria in the 300s B.C., and the Arab city of Fustat (later Cairo) in the 600s A.D. ensured its demise. The ultimate insult was levied against the city when Europeans arrived and began asking, “Where is it?” Earlier descriptions gave conflicting views. Looking for evidence of its location in 1799, a famous geographer, Major James Rennell, subsequently known as the Father of Oceanography, created an Egyptian map in England that incorporated all earlier information.2 He distilled the accounts of many travelers and historians; the result was a map (see insert, Map B) that accurately showed the position of Memphis in relation to the Nile and the Eastern and Western Deserts that dominate the landscape today.

Rennell believed, as did others, that the ancient bed of the Nile River was raised because of sediment. It then overflowed and the overflow followed a new course, a channel carved out by the river in the eastern part of the floodplain. This new bed served as the course of the Nile in Rennell’s time and with some changes continues to this day. This division of waters formed an island that became the land on which Memphis was built (see insert, Map B) and with time, the old riverbed silted up. The diversion of water was hastened by man-made channels and dykes, which served to protect Memphis once the land in and around it was reclaimed. These same waterways helped the temple-builders of the city gain access to the limestone slabs of Tura. Once they were developed further, they would also later serve Merer in the time of Khufu to deliver this same stone to the pyramid site.

Even in predynastic days, Memphis was everything that an ancient Egyptian could want, and it was named “enduring and beautiful.” It was probably first sparsely settled in prehistoric days (6000–4000 B.C.) then developed further by Menes, founder of the First Dynasty (3100–3050 B.C.), after which, it became the capital city of ancient Egypt. As pointed out by historians, it was in a strategic position to command both parts of the kingdom, south and north, because it lies at the junction of the delta and the Nile valley (Map B, see insert, and Map 2). With its port, workshops, factories, and warehouses, it was a natural regional center of commerce, trade, and religion. Papyrus paper was made in quantity in the wetlands of the delta and the floodplain swamps of the Nile valley and could be brought here for export. The trade route for grain, and products such as paper, began at the port of Memphis and led by way of the Pelusiac branch of the Nile to the large port centers in the eastern Mediterranean.3 Later in the 300s B.C., the city of Alexandria would serve the same purpose, and it would be in a better position commercially to exploit the markets. By then Memphis was in decline.

In Memphis in the very early days, circa 3500 B.C., settlers lived on the outskirts of the town in reed huts or in floating homes on skiffs made of papyrus. They included hunters, fishermen, and cattle herders; all people familiar with a marshy terrain. The water world was the focus of their life. They used papyrus stems gathered from the nearby swamps for boat making, weaving, and thatching or, tied into bundles, for all sorts of construction. When used for construction or rope making, the stems were cut then dried. But, often the stems were peeled while fresh in order to obtain flexible strips of green skin from the stems, as seen in a 1400 B.C. tomb drawing in Thebes.

Collecting and peeling papyrus stems (Tomb of Puyemra, Thebes 1400 B.C. after N. de Garis Davies).

These strips of skin are supple and long and make excellent material for weaving. Mats and baskets were produced this way, as well as woven sails for the thousands of small reed boats that plied local waters. Such papyrus skin is still commonly used for weaving in Africa today. After the stems were peeled, the soft pith at the center of the stem was left over and must certainly have attracted the attention of children sitting there as their mothers weaved. Possibly, as kids do, they began copying their elders and used the long strips of soft pith to make mats of their own. Even more fun would have been squashing the pith mats, after which, if they were left to dry, humankind would have a rough, early form of paper.

The process was further refined by using thin slices cut from the pith, which were laid rather than woven, and then evenly pressed, rather than just squashed. From this process a thin, durable sheet evolved and thus was paper born.

It would catch on quickly once people realized its potential. We see this when the children’s father comes home. He is a potter and at work he decorates pots with dark-red painted pictures of animals, people, and boats. Not much of a job, but he is curious and interested in life and in things like the dry, white, feather-light mats his kids left behind on the floor of their simple mud-brick house or reed hut.

This is the day after his wife finished weaving some window mats. Made from papyrus skins, they are finished just in time for the rainy season. He turns the product of his children’s handiwork over in his hands. His oldest child wakes from her nap, comes to him, and he shows her how to decorate it using the tools of his trade: a reed brush and colored inks. He is also a recorder for the village chief and must tally the grain that is stored in the village granary. He comes to realize that using this simple mat of papyrus pith is much easier than spending his time scouring the neighborhood for smooth stones, flat bones, shells, or pieces of pottery from his workplace.

Now aware of the potential, and given the inks, pens, and brushes at his disposal, and the great need of priests for records of temple stores and supplies, and that of the village chiefs for agricultural accounts, he improves on it. His career goes forward. He is soon known in the region as a scribe, things begin to look up markedly, and he gives thanks to the gods for his family, his kids, and this new medium, which is now called p’p’r’. This name for it meant “that of the pharaoh” or “the pharaoh’s own,” indicating that any paper in Egypt made from papyrus was the property of the king, since paper manufacture was at that time a royal prerogative, on top of which the plant itself was sacred.

By tradition, papyrus paper was said to have been invented in ancient Memphis,4 and in time papyrus paper factories dotted the landscape in swampy regions, such as Fayum, the delta, and the floodplain. There were probably many more manufacturing centers in operation than those indicated in Map 2, but these are the ones of which records survive.

MAP 2: Egypt in Roman times, showing papermaking centers.

Once Egypt was taken over by the Greeks, the plant was called papyros. The Greek writer Theophrastus uses that term when he writes about the plant used as a foodstuff. When he refers to its use as a nonfood product, such as in rope, baskets, or paper, he uses a different word, byblos, or βύβλος, which is said to be derived from the name of the ancient Phoenician town of Byblos, a major port where papyrus paper was traded in quantity. One expert thought this was simply another example of calling an item after its place of origin, much like calling a dish “china.”

Usage further leads us to the term biblion, which meant a book or small scroll, and “bible,” the English word for that special Christian book.

No matter when or how all this happened, paper, once invented, would be improved on with every generation as the sheets became stronger, more pliable, and thinner—so much so that there is little difference between the ancient sheets and the modern papyrus paper made from plants cultivated in the shallow waters of the Nile today. The only difference is that the modern paper in Cairo is destined for the souvenir market rather than the stall of an ancient paper seller.

In its own way, a roll of papyrus paper is a sophisticated product, something that did not appear de novo, or by accident, like, say, the invention of fire. Primitive man using a thin wooden shaft to drill a hole in an axe handle drives the point too fast; the wood catches fire and, presto, a dramatic moment happens in history. But with a roll of papyrus paper it is more complicated. Not only must the sheets be fashioned, but the roll of a dozen or more sheets must be joined together in such a way that the joins are as smooth as the made paper.

Interestingly, it doesn’t require much skill to make papyrus paper. The better forms and higher grades employ sizing and polishing, and joining the sheets into rolls; perhaps at that stage some expertise is needed, but basically, the making of the paper itself is a simple process and fortunately, the technique was preserved by Pliny in his Natural History. Unfortunately, it was this same account that led to a monumental misunderstanding, as commentators and editors wrestled with that same section (xiii: 74–82). Pliny mentions paperworkers in ancient Egypt slicing the inner stem with a “needle.” Since modern papyrus paper is most easily made using a razor blade or sharp knife, it remains unclear what he meant. Whatever the instrument was that was used to cut the thin strips, it is still unknown and has driven scholars to desperation since 1492. They have subjected that passage to the minutest scrutiny, much of which is beyond the scope of this book. In order to gain some insight into what can be derived from all the argumentation, and from Pliny’s interpretation of the process, we must turn to a specialist. And it happens that one of the best took up the subject, Naphtali Lewis, referred to by many as the “doyen of papyrologists.” Lewis was a distinguished emeritus professor at Brooklyn College when I started writing my book of the history of the plant in the early 2000s. He died in 2005; I never met him, but his work is fascinating. His book, Papyrus in Classical Antiquity, is an expanded and updated version of his Sorbonne thesis.5

He was aware that one of the first things that strikes people about Pliny’s description was why he made such a hash of it. Perhaps, as Lewis noted in his book, the answer lies in the fact that there is very little evidence that Pliny actually saw the p’p’r-making process. Dr. Hassan Ragab, the founder of the Papyrus Institute in Cairo, did something more helpful than reading about Pliny’s account, which was actually re-creating the process in the 1970s.

Dr. Ragab went on to do a great deal of research into the ancient methods of papyrus papermaking, and in 1979 earned a PhD from the University of Grenoble in the art and science of making papyrus paper; meanwhile he brought cuttings of plants from Sudan back to Cairo and started cultivating it in shallow, protected areas of the Nile River. His method of making paper was as close as possible to that described by Pliny and has given birth to many centers in Cairo, the delta, and Luxor where scenes of what might have taken place in ancient time in the papermaking centers of old Egypt are reenacted daily.

In modern times, one of the few working papyrus plantations in the world is the 500-acre swampy plot that was established by the artist Anas Mostafa in el-Qaramous, a village in the eastern part of the Nile delta in the Sharqia region. Here Dr. Mostafa trained 200 villagers in the cultivation of the plant and the ancient method of papermaking.

The process begins with workers hauling in armfuls of green stems freshly cut from a nearby swamp, exactly as they did in ancient papermaking sites in Memphis, the delta, and Fayum. The sequence for collecting papyrus in the ancient swamps and plantations is well shown in a tomb painting (1430 B.C.) copied by Norman de Garis Davies,6 which shows papyrus collectors assembling bundles destined for the makers of boats, rope, mats, and paper. In the drawing, the ancient artist also used the scene to show us the ages of man, from a lad on the left pulling papyrus stems into a papyrus skiff, to a gray-haired, paunchy fellow carrying a bundle of stems.

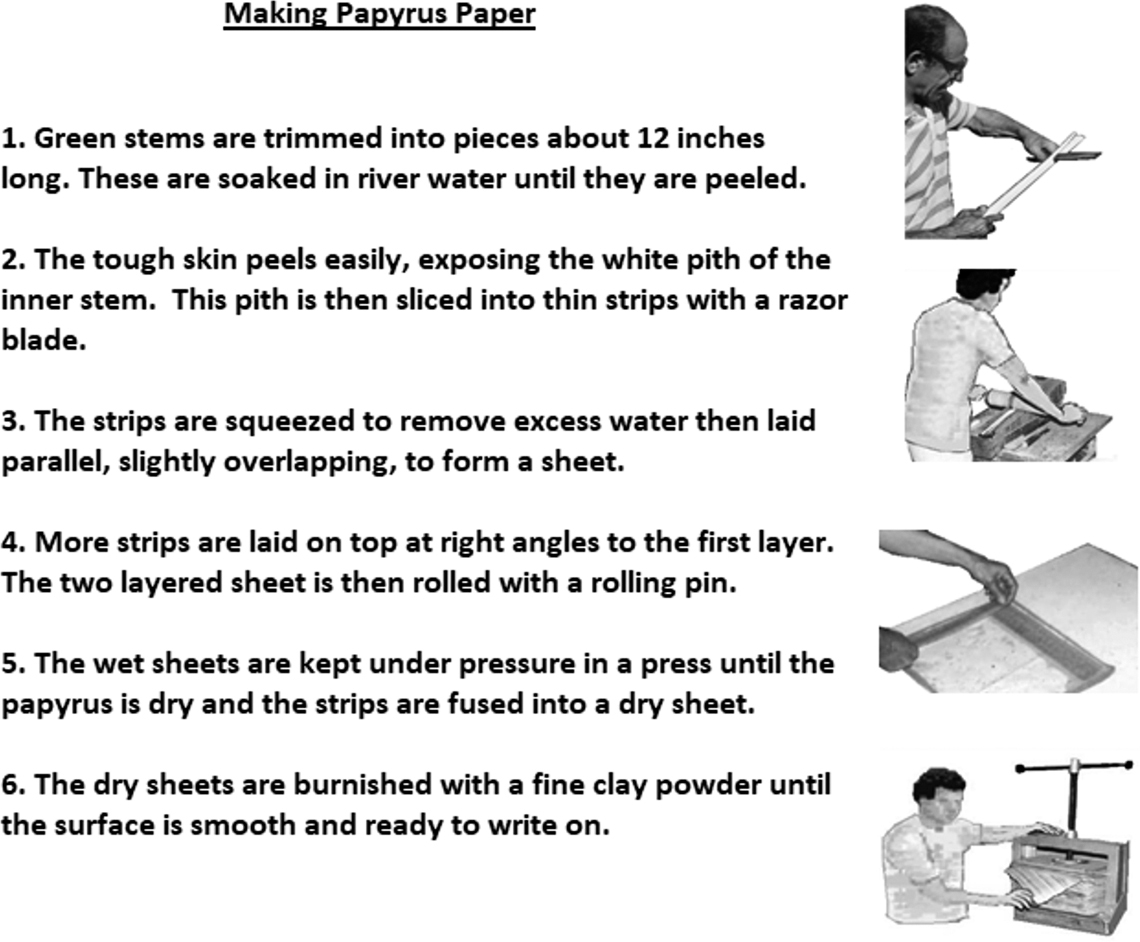

Making papyrus paper.

The next step after collecting the stems in the swamps is to cut off the tops, the flowering umbels, and the narrow upper stems. The remaining stems are then cut into foot-long pieces and left to soak in large basins of river water. Later they are taken up by another group of workers farther along the assembly line: the peelers. Since the stems are triangular in cross section, the tough skin on each flat side of the stem is easily peeled off with a razor or sharp knife, exposing the white pith of the inner stem. As the peelers work, the peels pile up until they are carried off to be woven into mats, sandals, small baskets, and all manner of handicrafts. The exposed white pith that remains is shaved into thin slices that are squeezed and pressed to remove excess water before they are laid out on a porous mat or matrix.7 Laid parallel and overlapping slightly, the slices form a sheet. More strips are laid perpendicular and the two layers are rolled with a rolling pin or hammered with wooden mallets to flatten the sheets.

This squeezing or hammering forces water out of the sheet, provides a natural adhesive, and allows the sheets to dry faster. Bridget Leach, former papyrus conservator at the British Museum, pointed out that the natural sap contained in the plant aids the process of beating and pressing to form a sheet before drying. The pressure applied during this procedure fuses the cellulose in each layer together physically and chemically; similar to the way that modern paper is formed. This is yet another way in which papyrus paper resembles pulp paper.8

The wet sheets of papyrus paper are laid on linen and compressed between boards, then bound tightly and set aside to dry, usually stacked against some sunny wall in the papermakers’ compound. Once dried, the presses are opened and the papyrus sheets are taken out to dry further. We now see a sheet of paper that can be used directly; or, if a finer quality is desired, it can be burnished with a fine clay powder until the surface is smooth.

At this point, the paper can be tested. According to Dr. Ragab, good papyrus paper is quite flexible. In addition to fingering the paper, high quality papyrus paper should be easy to bend, fold, tear, and must remain flexible. This is an indication that the natural juices that bind the sheet and keep it intact have been properly distributed throughout, a condition that only comes about if pressure is used while the sheet is fresh and still wet.

Once fashioned and properly pressed and dried it was very durable, so much so, Professor Lewis tells us, that in ancient and medieval times, papyrus books and documents had a usable life of hundreds of years. Pliny told of seeing papyrus documents that were 100 and 200 years old, and the Greek physician and philosopher Galen told of searching in books that were 300 years old. Papal documents up to 330 years old were handled in 1213 A.D. and there are references in the fourteenth century to papyrus documents from the reign of the Italian king Odoacer (476–493 A.D.).

How was this stability achieved? If there was any secret in the manufacture of papyrus paper it was that sufficient hammering with a wooden mallet, or rolling, or pressing during the early stage was essential. This allowed the strips to adhere to one another and the sheet to stand up to everyday wear and tear. Smoothing of the surface was not an absolute necessity, as it was perfectly easy to write on a freshly dried sheet as soon as it was made.

It should be noted that there are differences between the modern papyrus paper and ancient papyri, as pointed out by Adam Bülow-Jacobsen, former research professor at the University of Copenhagen. Ancient papyri show little or no signs of overlapping of strips. Since overlapping is not mentioned by Pliny, it may not be necessary. Bülow-Jacobsen also pointed out that the modern papyrus paper made in Siracusa, Sicily, though not strongly overlapped, is very soft and pliable; though it still lacks the feel of ancient paper, which is more like good-quality bond paper. On the other hand, modern paper made in Cairo and the delta, though it feels very much like the ancient paper, has marked overlapping, which the ancient material does not.9

After the dry sheets were removed from the presses, they could be joined together to form scrolls of twenty sheets (later referred to by the Romans as a scapus.) This was done using starch paste rather than glue, in order to preserve the flexibility of the roll. In the final stages of the assembly line in an Egyptian paper facility, large rolls 60 to 100 feet long were sometimes made up on special order. The joins were often so well-made that they have amazed researchers. How was it done? The secret is now out. All the right-hand edges of those sheets to be joined into a scroll were made with a strip missing. The result was a thinner joint once the paste was applied and the seam hammered or rolled. Professor Lewis thought it was astonishing that no one noticed for hundreds of years. 10

Papyrus was a resource treasured by the kings of Egypt. The plant, and the paper made from it, was viewed as a gift from the gods directly to the pharaoh himself, and all his subjects benefitted. It allowed Egypt to be papermaker to the world for thousands of years while history was in the making.

Centuries before Alexander’s conquest had made the Greeks the masters of the country, Egypt had manufactured papyrus paper by a carefully guarded process . . . and . . . went on to supply the whole Roman Empire. What a wonderful invention, so light, portable and easy to record information on via a reed pen, compared to the more cumbersome or more expensive writing materials, such as stone and metal plates, wooden and clay tablets, or leather. (C. H. Roberts, 1963)

After the roll or separate sheets were made, they were stacked or tied into bundles and sent off to Pharaoh’s agent for export. What did the earliest papermakers receive in exchange for their work? Certainly not cash, as the first coinage in general use in the western world was not introduced until 700 B.C. Perhaps they received grain, jewelry, cloth, or other goods from the agents for the crown, or the priests of the temple who often owned and operated large estates and in general acted in the interest of Pharaoh. In Roman times, when money was in circulation, the papermaker was regularly employed and paid by an estate manager.

The question of cost has teased historians of papyrus paper for years. Was it cheap or dear? According to the well-known papyrologist, T. C. Skeat, late keeper of manuscripts at the British Library, this is purely a modern question that no ancient writer ever expressed an interest in. Whatever it cost, it was regarded as essential and so had to be accepted.11 In order to further resolve the question, Skeat carried out a careful analysis of two sets of records taken from the extensive accounts and contracts written on papyrus and found in the Fayum region (Map 2). One record was from the estate belonging to Aurelius Appianus that was managed by Heroninos (249–268 A.D.), the other came from a graveyard at Tebtunis (45–49 A.D.), southwest of Fayum.

After careful consideration, he concluded that a standard roll would have cost about two drachma (roughly the equivalent of two denarii).12 Michael Affleck, librarian at the University of Queensland, tells us that Xenia, a very short book written by the Roman poet Martial on papyrus paper, could be bought for only four sesterces in 84 A.D., the equivalent of one denarius. Whereas a more decorative copy of his poems cost five times that. Affleck reckoned the average cost of a book roll to be eight sesterces, which covered the combined value of transcription and one roll of papyrus paper. This is close in value to the two denarii, or two drachmas earlier estimated by Skeat for a full roll of papyrus paper (made up of twenty sheets). A sesterce would be worth about $2.25 today, so the average cost of a book scroll would be about eighteen dollars, while a sheet would be about ninety cents.13

Skeat’s results did not differ much from an earlier analysis by Lewis, who thought the purchase of papyrus was not likely regarded as an expenditure of any consequence for a prosperous Egyptian, Greek, or Roman. It would have fallen, rather, into the categories of “incidentals” or “petty cash.” Lincoln Blumell, assistant professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University, makes it clear that for most persons above the social level of a peasant or an unskilled laborer, the use of papyrus for a letter was not regarded as expensive and was certainly not cost prohibitive. And in those days, when it came to letter writing, there was nothing like papyrus paper. Blumell tells us that of the just over 7,500 published letters from Egypt between the third century B.C. and seventh century A.D., about 90 percent are preserved on papyrus.14

This is not to say that papyrus paper was not carefully used. When corresponding with their paper suppliers, many an ancient maker of books used ostraca, pieces of shell, bones, or broken pottery, the ancient equivalent of Post-its. If a bookbinder would not spare a scrap of paper, ordinary citizens must have thought twice before using it for anything other than important records or correspondence.

And this attitude carried over to copyists who often drafted documents first onto wax tablets (pugillare) before transcribing them to papyrus paper. Luckily, when writing on papyrus, if a mistake was made while washable ink was being used, it was easy enough to sponge it off and start again, a quality that allowed some to take advantage of the situation. Skeat cited the interesting case of Silvanus, a magister in Gaul in the time of Constantius II. Enemies of Silvanus tried to ruin him by obtaining some of his letters, washing off everything except his name and inserting treasonable material. The letters were then shown to the suspicious, paranoid emperor, Constantius II. (Were emperors ever otherwise?) Silvanus, fearing the worst, acted rashly. The forgery was discovered soon after by the imperial court, but too late, the damage was done: Silvanus had been assassinated in Cologne in 355 A.D.15 To get around this, it was possible to use permanent ink that, once dried, was impossible to remove. Such ink often soaked into the papyrus so that the only way to change a typo was to white it out, which left a telltale mark.

Given the fact that paper was in demand and that in many cases it was also possible to scrub off the writing, why wasn’t a major recycling industry taken up? Perhaps, as noted by Skeat, it was because of a sense of caution and suspicion, the same feeling that makes some of us think twice before using something that has been recycled today. In Skeat’s view, secondhand scrolls were looked down upon as inferior material, fit only for such things as drafts or scribbling paper. Literary allusions also tell us that the reuse of papyrus rolls by a poet or writer was cause for contempt. Thus, although a number of papyri were reused, an even larger number (75–91 percent) were not and wound up on the rubbish heap after only one use (i.e. written only on one side). They were later found by the likes of Grenfell and Hunt, who noted that they were torn in half before being discarded—they were not left there by accident.

Ancient authors were also well aware that any unsuccessful book in those days would be consigned to the fish and grocery markets or the schoolroom as scrap.