Growing and Managing Papyrus for Paper

As mentioned earlier, the largest change after the Roman takeover of Egypt was privatization; many swamps were owned outright and the production contracted out as the swamps became managed resources like any other agricultural land. Three contracts reviewed by Napthali Lewis exist from Roman times and show how papyrus was managed as a crop.

The first was an application from a man named Harthotes in 26 A.D. to harvest papyrus in the Fayum region. The interesting thing about this request is that Harthotes was seeking permission to harvest from a wild swamp, a drymos.

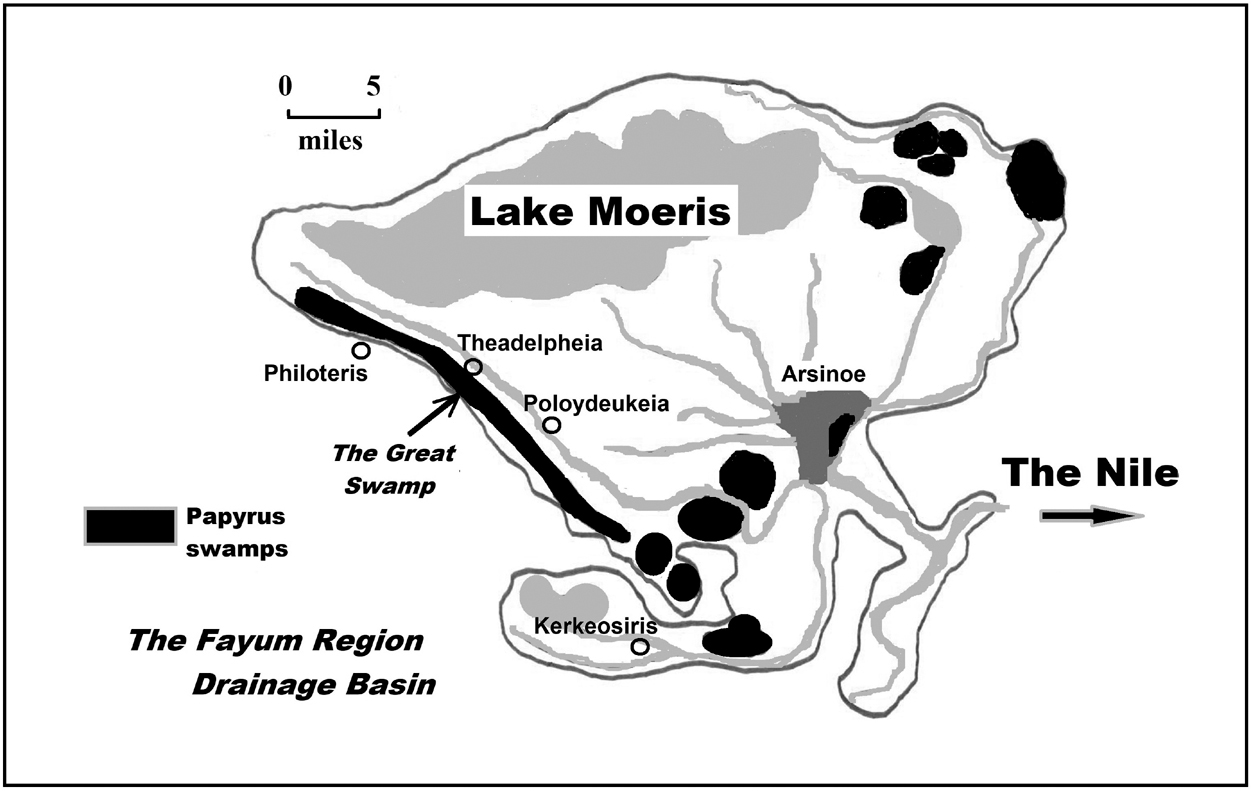

MAP 3: The Great Swamp in the Fayum Region (after original map from Univ. Leuven Fayum Project, courtesy of Prof. Willy Clarysse).

Harthotes if successful, would have access to an enormous wetland called the Great Swamp (Map 3). It was twenty miles long and stretched from the ancient Egyptian town of Philoteris northeast to the village of Theoxenis. Since it was about a half mile wide, it amounted to ten square miles or 6,400 acres. His application reads as follows:1

From: Harthotes, son of Marres.

To: Aphrodisius, son of Zoilus, contractor of the papyrus holdings of Julia Augusta and the children of Germanicus Caesar.

If I am granted the concession to gather papyrus from the vicinity of Theoxenis to the borders of Philoteris—i.e. reeds and papyrus from the drymos—and weave mats and sell them in any villages of the nome I choose for (the remainder of) the 12th year of Tiberius Caesar Augustus, I undertake to pay four silver drachmas and fifteen obols together with the customary expenses, additional charges, and receipt fees, all of which I will pay in three instalments, in Epeiph, Mesore, and the month of Sebastos next year,* if you see fit to grant me the concession on the foregoing terms.

Farewell.

Year 12 of the Emperor Tiberius Caesar Augustus.

Lewis pointed out that this is a remarkable document on its own, regardless of the papyrus harvest, in that it gives evidence of an estate belonging to members of the imperial family (the children of the deceased Germanicus). For the economic history of Roman Egypt and the Roman empire it documents one of the family’s sources of income. Germanicus was a major player among the Roman elite. He was adopted by his paternal uncle, Tiberius, who succeeded Augustus as Roman emperor a decade later. He was also the maternal grandfather of Nero. His children, who are indicated as the owners of the Great Swamp included Caligula, Emperor of Rome, and Agrippina the Younger, Empress of Rome. Another owner of the Swamp was Julia Augusta, who is none other than Livia, the widow of Augustus. She was given the name Julia on the death of her husband and was deified by her grandson Claudius, of whom we will hear more in the next chapter.

Another significant detail is the small sum of money offered for the right to gather wild-growing reeds and papyrus stalks over a twenty-mile stretch of marshland. Four silver drachma and fifteen obols would be about fifty-eight dollars today. Presumably there were other swamps in the Fayum region that were used by the papermakers, who paid much more for the right to harvest, as we will see in the other contracts.

The two other contracts describe the workings of plantations, one from 14 B.C. and a later one from 5 B.C. They deal with swamps in the delta that were kept as plantations and illustrate the difference between protected and cosseted swamps and those left in the wild state. The stems of the protected plant were generally superior as well as homogeneous in size. In order to insure that plant stems from the plantations remained in premium condition, Lewis noted that “a whole battery of provisions is clearly aimed at maintaining the productivity of the plantation and the quality of the product. Thus, the lessees are obliged to cultivate the plantation in its entirety, neglecting no part of it. Again, they may not sublet but must see to the operation themselves. They must use the proper tools and methods, and must maintain the waterways against blockage or deterioration.” Pasturing and watering of animals, common in the wild swamps, was not permitted in the plantations, since the animals would inevitably trample the tall stalks and probably eat the young shoots.

Under the contract, “Woven products could be made from the wild growth . . . but the prime plants . . . destined no doubt for paper-making, were too valuable to be wasted on such inferior uses . . . the bulk of the production was to be cultivated to maturity and harvested at full growth.”

He also found the contracts interesting because of the clauses fixing the going rate for hired labor, which was made up of free men rather than slaves, thus eliminating competition for manpower. Lewis pointed out that the paper factories were able to operate twelve months a year because the papyrus plant was harvested year-round. Contracts showed that harvest went on in one case from June to August; in another, daily from June to November; while the lessees of another plantation agreed to pay a rent of 250 drachmas a month in the six months from September to February ($2,250 in modern terms), and more than double that amount in the other six months.

What did they get for their money? In the earlier contract a husband and wife, lessees of a helos papyrikon, a proper plantation, acknowledge a loan of 200 drachmas ($1,800) to be repaid a drachma a day; and in lieu of interest on the loan they would deliver to the owner each day, and sell to him at less than the market price, a portion of their daily harvest of papyrus stalks, up to a six-month total of 20,000 one-armful loads and 3,500 six-armful loads of papyrus stalks. This averages out to be some 200 sizeable bundles of stalks daily! The owners could then resell or use this papyrus “interest” at a large profit.

In harvesting, as depicted on the walls of Egyptian tombs, the stalks were pulled up from the rooted base and tied into sheaves, which people then carried away on their backs or in boats. Under the terms of the contracts, Lewis noted that at the end of the first century B.C. papyrus stalks were delivered and marketed in units designated as one-armful and six-armful loads, “a detail which suggests very strongly that the techniques and practices of papyrus harvesting had changed little if at all through the ages.”

As to the total harvest, since the above 200 bundles from the contracted swamp were only about 10 percent, a rough estimate of what was taken from the swamp daily would be about 2,000 bundles or about eight tons dry weight. And this was only one of many swamps throughout the country.

In combination, these three documents tell us that from March onward, the yield of papyrus stalks increased, with June through August constituting the major harvest period of the year. The explanation lies, no doubt, in the hydrology of the region. From September to March, the floodwaters of the Nile would be at their highest levels and access to the plants would be more difficult, requiring the use of boats.

Obviously all of the management and production efforts by the Romans were done for a purpose, to provide papyrus paper for a market that continued to expand throughout their empire and beyond. Luckily, they were dealing with a very productive plant.2