The Emperor and the Lewd Papermaker

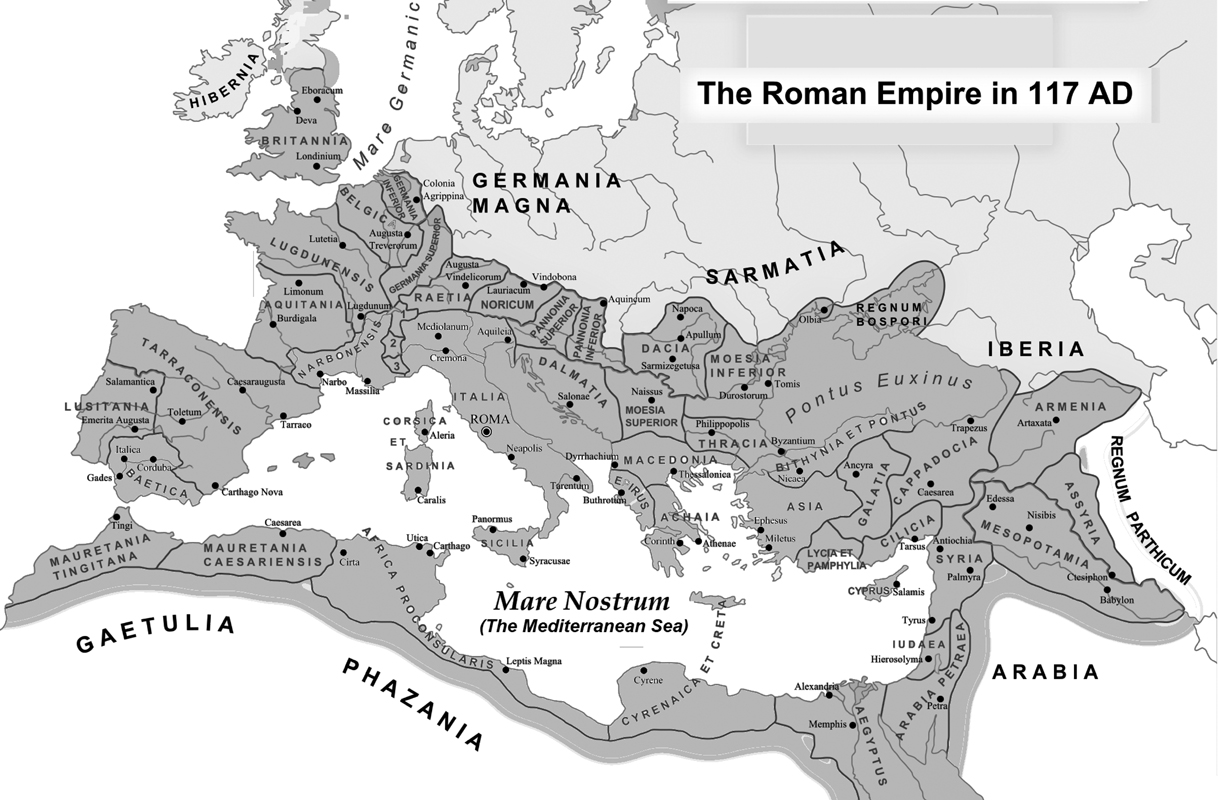

By the first century A.D., papyrus paper was available throughout the Roman Empire, a market that consisted of the area stretching from Hadrian’s Wall in the northern wilds of Caledonia, east to the dry karst plateaus of Cappadocia and the Caspian Sea, south to the lush valley of the Nile, and west to Lixus in the deserts of Mauretania. An empire of over two million square miles surrounding the Mediterranean (Mare Nostrum, “our Sea”) and comprising a population of almost 100 million people, it had an enormous daily demand for food, drink, and paper. To make things easier, the Romans simply made Egypt a province. In so doing they were formalizing a long-standing arrangement. Egypt had been a major supplier of grain for many years. But even though Egypt was now a province, it was still a major trading partner.

MAP 4: The Roman Empire in the 1st century (Wikipedia).

In exchange for luxury imports and raw materials such as gold coins, glassware, olive oil, wool, purple fabric, metal weapons, and tools, Egypt exported gold, linen, glass, painted pottery, papyrus paper, and rope.1 For years Egypt also sent grain, which fed the ports, cities, and populace of Italy, but grain shipments were essentially a tax in kind sent to Rome instead of money.2 The amounts rose to more than 100,000 metric tons per year under the first emperor, Augustus.3

For many items other than grain, the export business was a two-way street and thrived on finished products in preference to raw materials. Egyptian exporters saw it as an opportunity to export value-added items, a practice that goes on in many countries today as well as it did in ancient times.

The first instance I saw of the value-added principle in action was in Ghana in the 1980s when I was consulting on the environmental impacts of a very expensive dam. Aluminum ore was locally available in quantity and the new hydroelectric facility near Accra was destined to be used to provide the power to smelt the ore. But to make exports competitive and profitable, economists on the project suggested it would be better to export improved or finished products. Instead of exporting ingots, they thought Ghana would be better off exporting aluminum pots and pans.

When papyrus paper left Egypt in sheets or rolls bound for the Roman markets, it represented a marvelous example of the value-added principle. Papyrus paper needed little or no input, unlike grain that was sent raw to be ground into flour by the Roman mills, gold that needed to be refined and recast, or glass and linen that required much initial work, and in the case of producing glass, pottery, and refined gold, fuel was needed in a country where wood was scarce. The kilns and furnaces in Egypt often used chaff, waste from grain milling, dried papyrus stems, and as a last resort local bushes and stunted trees from arid regions.4

In the case of paper, it was a finished product that was cheap to make and used local resources that were self-sustaining. It was also a product that was kept under close watch by a cartel of plantation owners who harvested year-round and kept the paper factories operating twelve months a year.5

Under Roman administration, Egyptian papermakers were subjected to strict quality controls as paper was now graded against standards set by Rome. The cartel rose to the occasion and produced whatever was necessary, from the high-quality paper of the imperial grades down to the lowest form used as wrapping paper (Table 1). They were so successful through the years that it was even suggested that Firmus, a Moor ruler in Muretania who set himself up as an imperial pretender in 273 A.D. (a position from which he was later deposed), might have been heavily invested in the Egyptian paper trade.6

By the time Augustus had taken over the Roman Empire in 27 B.C., the papermaking industry needed to be reorganized and standardized. For thousands of years, Egyptian papermakers had made paper in all sorts of lengths and widths. According to Jaroslav Černý, former professor of Egyptology at Oxford, the papyrus rolls of the earlier dynasties in Egypt were about 12½ inches (32 centimeters) in height, which was the dimension that remained constant; similar to the case when you buy wallpaper where the standard dimension is referred to as the height. The “length” will vary depending on where the roll is cut. With papyrus paper, since the rolls were made of twenty sheets, the width or length of a 12½ inch roll would be about 160 inches. This provided plenty of space for most common writing tasks. If this fell short, paper sheets could be added on as needed. Often the ancient rolls that were 12½ inches in height were sliced into four segments providing four rolls for office use, each 2¼–3½ inches in height and 160 inches long. For literary use, the roll cut in half provided two long rolls, each 6¼ inches in height.7

Table 1. Grades of papyrus paper in common use during the Roman period, based on Pliny. Ranked by quality and width of the sheet.

With the founding of the empire, the Romans defined the best-quality paper as a sheet appropriately called, charta augusta8 that was said by Pliny to be 9½ inches wide (he never mentioned height). A more diminutive sheet, charta livia, one inch shorter, was named after the emperor’s skillful, unpretentious wife, Livia, part owner of the Great Swamp in Fayum.

Augustus had many things on his mind in the early days of his realm. He was a busy man embarking on a large program of reconstruction and social reform. Did he know or care about papyrus paper? He was a patron of Virgil, Horace, and other leading poets and interested in ensuring that his image was promoted throughout the empire, thus it is certain that he took an active interest in statues, coins, and perhaps enjoyed the fact that the best paper of his time bore his name.

His stepson, Tiberius, the second emperor, must have acquainted himself with the details of making papyrus paper, since in his time the Senate called attention to supply problems with papyrus paper. Tiberius was very much interested in libraries and thus would have had concerns over the paper that filled them. He built the fourth imperial library as a tribute to his stepfather who died in 14 A.D. The library was in the Temple of the Deified Augustus next to the Augustinian palace on the Palatine Hill. Tiberius also created the position of national librarian, the procurator bibliothecarum, and appointed Tiberius Iulius Pappus to the post to oversee all the emperors’ libraries.9, 10

Claudius, the fourth in succession, seems to have had less interest in libraries, but more in writing. He was a rare ancient scholar who could write about the new empire as well as obscure antiquarian subjects. He even proposed reforming the Latin alphabet with the addition of new letters. Since he wrote copiously throughout his life, including Etruscan and Carthaginian histories, he must have been well aware of the deficiencies in charta augusta, the paper that, until then, was considered the best paper bar none. It did not please him; he was upset by what he thought was the high degree of transparency. The paper was so thin the ink showed through. Lastly the sheets were too small.

He thus directed the papermakers in Egypt to produce a paper that was larger in size and thicker. They responded with a two-ply paper that had a groundwork made of second-quality strips over which were laid strips of first quality. In so doing, they produced a paper that was the best papyrus paper of Claudius’s day. Another advantage was that it could be written on on both sides, which suggests it had perhaps been polished on the verso by rubbing with pumice stone or a piece of bone or ivory.

Claudius must have been justly proud of this accomplishment. He had commissioned a paper grade famous enough to be placed on Pliny’s list, even though the list did not appear until after Claudius’s unexpected death. On that list, which appeared in 79 A.D. after Pliny himself had died from asphyxiation following the eruption of Vesuvius, the ten categories were ranked by quality and width.11 In modern terms, if twenty sheets of 8½ by 11 inch standard bond paper of today were joined in a typical roll, the result would be a continuous piece of paper fourteen feet long that would still only be eleven inches in height. Under Pliny’s system it would perhaps be designated charta moderna.

Once Claudius’s paper was launched, the great paper storehouses of Rome, the horrea charteria,12 would be continuously resupplied with a standard product that would satisfy anyone. But, about the same time, another paper appeared on the market: charta fanniana, which rivaled the new claudiana because it was just as good, but cheaper. Also, it was the first major paper product ever made outside of Egypt since the beginning of recorded time. No mean feat.

The man who accomplished this was Quintus Remmius Palaemon, called Fannius, a former weaver and slave and later a freedman. He became one of the best-known teachers of his time and in the process, was flaunted as the poster boy of self-improvement.

It seems that as a slave, when he was sent to school with his charges, the children of his master’s house, he acquired the rudiments of learning while sitting around waiting to take them home. He soon developed powers of narrative, a style in speaking, and a mastery of poetry, enough so that he became the equivalent of, say, a high school or college English teacher in today’s world.13 After being freed, he was considered one of the most desired teachers of his day. He opened a popular school and managed his private estate with such care that he became a wealthy man.

His largest failings were referred to by the author Suetonius as his “unbridled licentiousness in his commerce with women,” and his weakness for “foul indecency.”14 So steeped was he in luxury that he bathed several times a day and he was infamous for his habit of “mouthing” every man he met. All this turned Tiberius and later Claudius against him. They thought he should not be trusted with the education of boys or young men. But he caught everyone’s fancy by his remarkable memory and his readiness of speech. The Greek form of his name Palaemon meant “the honey eater,” which the Romans thought just about summed him up.

He reminded me of several high school and college English teachers I knew who seemed to either know everything about life from real experience or from what they had read (you never knew which), and as a result they took on racy reputations that they may not have deserved.

Was Fannius really that bad? After thinking about all those biographies, films, books, comics, and videos of degenerate Romans high and low throughout history (the names Nero and Caligula come immediately to mind), Fannius’s bathhouse antics, kissing males and lewd behavior would seem bland in comparison. It has also been said that he was the object of a smear campaign by Suetonius.15

Anyway, Fannius was no fool and he obviously knew his way around. For example, he started a shop selling secondhand clothes for which his experience as a weaver must have been of great help. And soon he had a business empire of his own and an entree into the schools and the writing life, all of which involved papyrus paper. Perhaps his ears perked up when he heard that Emperor Claudius had called for a new type of paper, and with confidence, he probably said, “I can do that.”

What was he thinking of? He was not only taking on an emperor, but one that had all but called him a pervert. This could have been a match-up made for reality TV: Fannius, the macho-driven, self-made, wealthy, Donald Trump-like entrepreneur faces the royal emperor, Claudius, who sometimes lunched with plebeians, but was thought to be bloodthirsty, cruel, overly fond of gladiatorial combat and executions, and very quick to anger.

Could Fannius do it? He must have known, perhaps from his days as a weaver, that cloth and paper were sometimes better thought of as living things, because, unlike bricks and mortar, they could be changed, gussied up, even made over until they were unrecognizable.

The old bonnet that gained a second life because of a few artfully placed feathers, or a shawl changed by a dye job was what he had in mind. In the case of papyrus paper, he knew that there was still a lot that could be done even after the paper left Egypt. Perhaps he discovered by experiment, as I did, that papyrus paper soaked overnight becomes quite soft and pliable. It can then be rolled with a rolling pin until it becomes a very thin sheet, thin enough to read through. In my case, I took a piece of modern papyrus paper made in Cairo, cut it into a square exactly 7½ by 7½ inches, soaked it, and rolled it, and within a short period of time found it had expanded to over 8½ inches square, and by then it was thin enough to read the cover of a gourmet food magazine through.

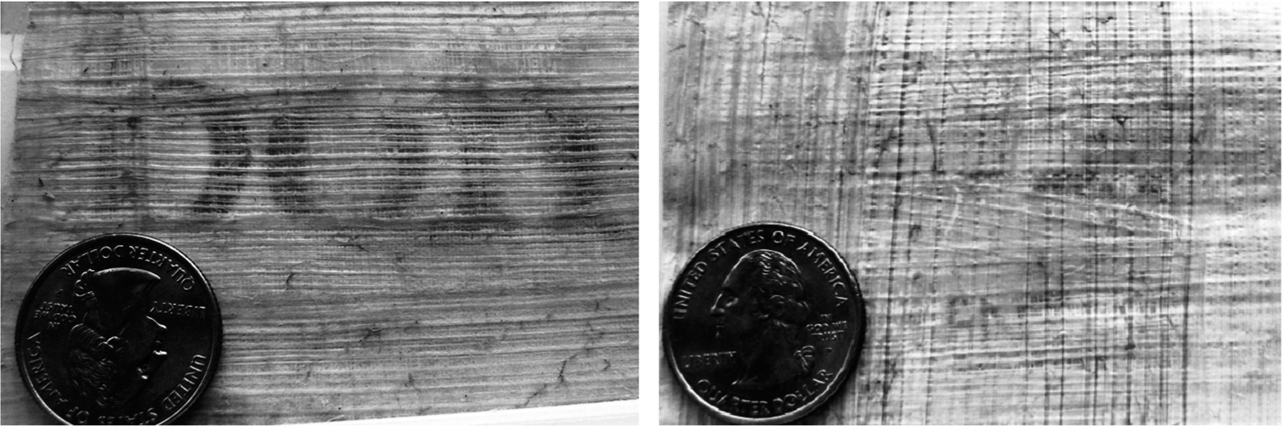

Papyrus paper after rolling while wet lying on a magazine (left), right same, paper after a third layer was added.

Then I soaked up some dry slices, also obtained from Cairo via the Internet, and added a layer to the thin sheet. In adding the new strips, I cut them to the newly increased size, 8½ inches, and did not overlap them. After more pressing, rolling, and malleting I had a three-ply sheet of new paper. And because I had added the new layer in a horizontal fashion (as in the recto side of the original two-ply sheet) I could now write easily on both sides.

Pliny never told us exactly how Fannius did it, but Lewis suggested that a correct reading of what Pliny did say implies that Fannius started with a more common, cheaper grade of Egyptian paper, charta amphitheatrica, and added a third layer after making it thinner.16 In so doing, Fannius would simply have been doing in his workshop in Rome what was being done on occasion in ancient Egypt when a special, high-quality paper was needed. For example, the Papyrus of Ani and that of Greenfield, according to Wallis Budge, were made of three-ply papyrus paper.17 And, if it was good enough for Scribe Ani, it would also serve Fannius and the rest of the Roman Empire, including Claudius Caesar.

By the time Pliny’s list appeared, Fannius, like Claudius, had passed on; but by then Fannius had entered the ranks of emperors, at least to the level of Augustus and Claudius, as namesake for a type of paper. Despite what Suetonius had said about him, he had finally gained a place in history.