Constantinople and the Long Goodbye

Our mentor, Cassiodorus, lived most of his life in an Italy that, by the sixth century, had become a backwater. The Roman Empire of his time was a shell. The Goths, Huns, and Vandals had emptied the coffers, burned the libraries, trashed the archives, and taken control. A superb and diligent bureaucrat even at a young age, Cassiodorus went to work for the Goths when he was thirty-eight and rose rapidly in their political system. He had great connections under the old regime, where his father had been the governor of Sicily and Calabria, and his grandfather a tribune. Cassiodorus knew his way around and how to get ahead. Professor James O’Donnell, librarian at Arizona State University, historian, author, and authority on Cassiodorus, referred to him as a man who had an “aptitude for compromise with power,” and also “a great seizer of opportunities,” he was someone on the side of change and innovation.1

In Ravenna under Theodoric the Great, the Ostrogoths greatly appreciated his literary and legal skills. As Christians, they had taken over the reins of government, and with that came a nightmare, an enormous legacy of documentation, everything connected with the business of church as well as state. It all seemed to require written responses of a lengthy and careful nature. Snowed under by this avalanche of papyrus paper, it helped that they had a man who embraced the task. His appointment as praetorian prefect for Italy effectively made him prime minister of their civil government and he was often entrusted with drafting significant public documents. He kept copious records and letter books concerning public affairs, all on papyrus paper, which he, like Saint Augustine, felt was one of the world’s greatest inventions.

Cassiodorus and a papyrus codex (after Gesta Theodorici 1176).

His boss Theodoric was so swayed by him that in due course he removed the tax on paper, which Cassiodorus thought to be a fine moment in the history of government. By 534 A.D. the people had a great supply of papyrus paper in Italy and it was tax free, thus, “a large store of paper . . . laid in by our offices that litigants might receive the decision of the Judge clearly written, without delay, and without avaricious and impudent charges for the paper which bore it.”2

What a man! And remarkably cool-headed as the Goths continued their wars, beheadings, tortures, and all manner of blood-spattering incidents. If one were to read only Cassiodorus one would never suspect they were anything but a docile church-going flock.

Following the death of Theodoric’s young successor, Athalaric, in 534 A.D., and Justinian I’s conquering of Italy in 540 A.D., Cassiodorus left Ravenna to settle in the new seat of power, Constantinople.

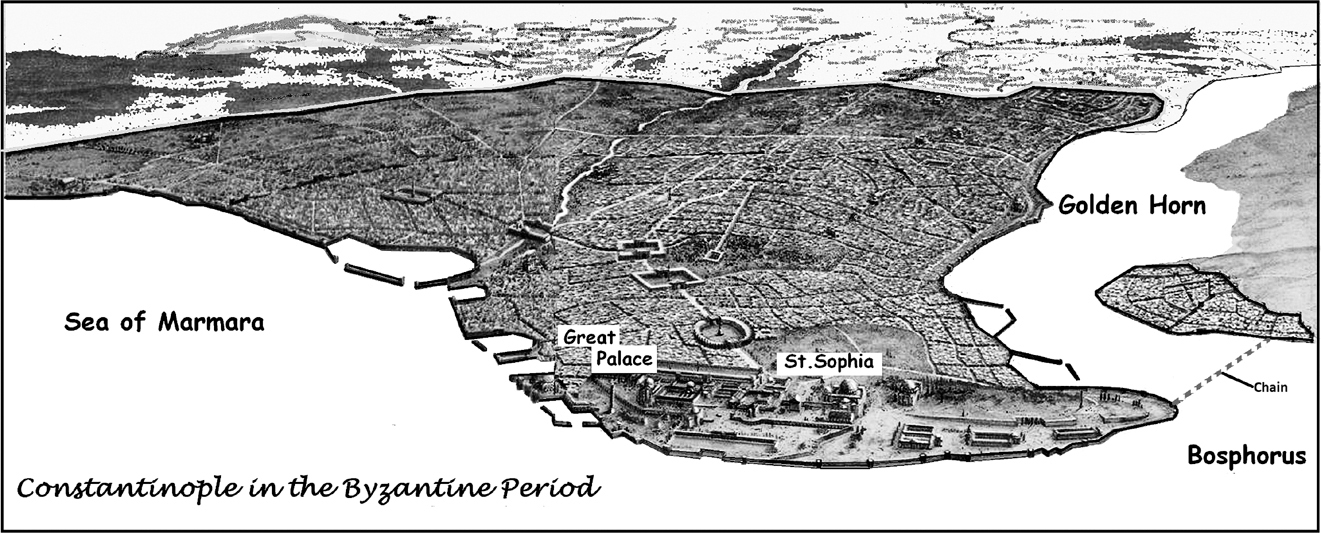

In Cassiodorus’s day, Constantinople was a walled city surrounded on three sides by water. It reflected wealth, power, and protection and, like Rome, it was built on the rising ground of seven hills that provided then, and now in present-day Istanbul, spectacular views of the Bosporus. A chain could be placed across the Golden Horn estuary so as to cut off further boat traffic in order to protect the flanks of the city.

It was the largest city of the Roman Empire and of the world, and so its emperors no longer had to travel between various court capitals and palaces. They could remain in this Great City and send generals to command their armies as the wealth of the eastern Mediterranean and western Asia flowed to them.3

Aerial view of Constantinople in the Byzantine period (after DeliDumrul–Wikipedia).

In the eighth century A.D. the Theodosian Walls (double walls with a moat) kept it impregnable from land, while a newly discovered incendiary substance, known as “Greek Fire,” squirted under pressure allowed the Byzantine navy to destroy Arab fleets and keep the city safe.

Grain arrived regularly from Egypt, spices and exotic foods came from India, grapes and wine from local vineyards, while produce from extensive gardens and abundant local fisheries was brought into the city daily. This supplemented vast quantities of stored provisions, while the Lycus River that ran through the city provided abundant fresh water to many underground cisterns and reservoirs. Constantinople was thus famed for its massive defenses, and though besieged on numerous occasions, it was not taken until 1204 when it was sacked by the army of the Fourth Crusade.

As for paper, Nicolas Oikonomides, the illustrious Byzantine scholar, noted that papyrus from Egypt was still being imported into Constantinople by the shipload in the tenth century. It was regarded as the choicest of materials.4 He pointed out that although parchment was being used to make new books, and to transcribe older papyrus codices, it was still quite expensive. It made up almost a third of the cost of a book. Also, the supply of parchment was seasonal, since slaughter of the animal mostly involved the sheep, and happened at a particular time of the year, and it was not always of the desired quality. There were frequent shortages in Constantinople, especially in the winter months. Papyrus paper could be ordered in large enough quantity so it could be stored as well as used to satisfy daily needs. Michael McCormick, in his concise economic history of the era, The Origins of the European Economy, points out that the papal chancelleries of the 840s A.D. had so much papyrus paper in reserve that one piece was at least thirty-eight years old from the day it was made in Egypt until the day it was used.5 To the east of Constantinople, stored papyrus paper served the Muslim governments equally well. According to historian Matt Malczycki, the caliphs in Baghdad around this time kept tabs on papyrus paper in their storehouses.6

So, throughout the world, from Anglo-Saxon England to Baghdad, and until the tenth century, papyrus served everyone’s everyday needs and more; this situation did not change even after 794 A.D. when an Arab paper mill was started up in Baghdad.7 The mill used the new Arab improvisation on the Chinese method, a process that involved the pulverization of linen rags in order to make a slurry of pulp, and the pouring of this slurry onto frames for drying. The laid rag paper produced this way was cheap but, according to Oikonomides, it was not very strong. Chinese paper was made out of wood fiber, such as mulberry bark, but the earliest paper made in the Muslim world was made of linen rags, which turned out to be a useful idea, as the flax plant was grown and linen cloth made in quantity in Egypt especially under Fatimid rule (969–1171). The new rag-paper industry would thus be a natural adjunct to the large linen-weaving industry. The most interesting part of this story is how the Arabs, after latching onto the Chinese process and changing it, now had a use for their recycled linen waste left over from their cloth industry. For hundreds of years, they manufactured all three in Egypt: papyrus paper for the Christian world, rag paper for the Eastern Muslim markets, and linen cloth in quantity for everyone.

Constantinople found itself directly in the path of development of rag paper on the one hand and parchment on the other; yet papyrus continued to be used for ordinary everyday business. It is no wonder that Oikonomides tells us that up to the ninth century, the imperial secretariat preferred papyrus for important documents, such as the famous “Saint Denis Papyrus.” In this letter, Emperor Theophilus sought help from the Franks in turning the tide of Muslim forces in the Mediterranean, perhaps a prelude to the Crusades.8

With the end of the first millennium came a change in Europe. It was no longer economical to transport papyrus northward across the Alps. Though Italy was awash in papyrus paper (see insert, Map C), the new kingdoms north of the Alps throughout Frankland and as far as Northumbria had to look elsewhere, and they did so. These kingdoms did not have the historic trade ties with Egypt that Rome did. And perhaps also they were following the example of the village priests and curates who, even if it was an expensive process, stocked their local church libraries with codices made of vellum and parchment. Thus the new rulers of western Europe turned to a locally produced medium for their everyday needs and said goodbye to papyrus.

Further north in Europe and England, the supply of papyrus diminished until it reached the vanishing point, and here we see what happens when Pharaoh’s treasure was at the end of its rope. As in modern times when we live far from the grocery store, we just have to make do. In the outer fringes of the Roman Empire in northern England, just south of Hadrian’s Wall, we find ourselves in a Roman fort called Vindolanda living in a military colony of Belgic Gauls in 100 A.D. surrounded by people they referred to as those “wretched little Britons.”9

Although papyrus paper still arrives with the monthly dispatches, and scrolls of the Acta Diurna reach us periodically so that we are still informed as to what is happening in the world, there is less and less paper included in the supplies that are sent to the fort. Now that the major source of paper is far away, we must learn to use what is available locally. In the other parts of Europe, the trend would be to start up a parchment industry; here the military establishment is a small enclave, a fort surrounded by forests not like the monasterial infrastructure of elsewhere. Anything needed for our daily existence that can be made of wood is a blessing. The commanding officer assigns a noncommissioned officer with woodworking skills to provide writing materials. That person decides not to turn to the inner bark of trees, as did earlier Romans; this is where liber of ancient days, the word for bark, comes from. The Latin word for book comes from liber (and the later English word for “library”). He looks instead to the light-colored wood of local trees: the so-called sapwood of birch, alder, and oak.

After cutting down a suitable tree, he saws out a block of wood approximately the size of the final half sheet (about 8 by 3 ½ inches); then, along the surface of the grain of the wet wood, he passes a nine-inch wide, very sharp, iron blade—perhaps contained in the frame of a large block plane. Very soon he has a pile of wide shavings about one millimeter in depth that will serve in place of paper. He treats them further by drying them under a weight so they won’t warp. Then, after a light sanding, he has a supply of small sheets that can be used for everyday correspondence as well as the needs of the army.

Daily and weekly accounts must be kept, work rosters, interim reports, lists of day-to-day needs, and daily checks on men and material have to be recorded. All this is done on what is referred to today as a “tablet,” though perhaps it is more rightly named “wood paper,” since it was used in place of paper, served the same purpose, and probably when first made was as flexible as stiff bond or postcard stock.10

The value of these postcard-size sheets lay in their use as interim material. Larger official reports, which became part of the official archive at regional level, were still drawn up on papyrus paper scrolls; but for all else the sheets of wood were more than adequate.

Discoveries since Vindolanda, especially in the fort and town at Carlisle at the western end of Hadrian’s Wall, show that these tablets were in wide use, and there is evidence that they were well-known in the Roman world. The third century historian Herodian, describing the death of the Emperor Commodus (180–192 A.D.) noted that the assassination was caused by the discovery that the emperor had made a list of proscribed persons, “on a writing-tablet of the kind that were made from lime-wood, cut into thin sheets and folded face-to-face by being bent.”

This is part of the picture of what a well-oiled and bureaucratic machine the Roman army was, and it is also further demonstration of how such a small number of ingenious, resourceful men could be used to police and control a wide frontier.

South of the Alps, as McCormick explains, the Roman church offices and the papal registry followed Saint Augustine and Cassiodorus in their preference for papyrus, which was “part of the conservative symbolic culture of papal power.” In other words, the demand for papyrus paper in Italy was based on the same kind of sacred church liturgical and bibliographic traditions that called for lead seals for documents (bulla in Latin, hence any important church manuscript became a “bull”), special handwriting, prose rhythms, sacred ties, and foldings, all to the glory of God, the church and the pope. One of these traditions demanded that documents of the early popes had to be written on papyrus, and so, in the papal chancery, papyrus was used to the exclusion of other materials, even though alternatives were available in parchment and vellum.

Another factor influencing the decision of the church’s preference for papyrus over parchment may have been security. The fact is that writing normally will adhere firmly to parchment or vellum and ordinarily cannot be erased by rubbing or washing; but even a tenacious ink like that made of iron gall can be removed. Because parchment is very durable, a thin layer can be scraped off the writing surface. This practice was put to use in teaching where the term “scratch pad” in the Middle Ages meant a palimpsest. This was a parchment used in the fashion of a schoolboy slate; any practice writing was simply scratching off to begin again. In the early Middle Ages parchment was even recycled by washing away the original text using milk and oat bran.11 With the passing of time, the faint remains of the former writing would reappear enough so that scholars could discern the text (called the scriptio inferior, the “underwriting”). In the later Middle Ages the surface of the parchment was usually scraped away with powdered pumice to prevent this reappearance of the ghost of the original text, yet irretrievably losing the writing. Hence the most valuable palimpsests today are those that were overwritten in the early Middle Ages.

None of this applies in the case of papyrus, if a permanent ink was used, scraping would leave a hole or scar, making it difficult to falsify a document. This was also a factor in the preference of some caliphs for papyrus over parchment. How could they be certain that their subjects or the person addressed in a letter or decree would receive the real thing? In this they were not alone: the popes also had the same problem. In both cases they were reluctant to give up the use of papyrus paper. Parchment was okay for books, but not for their letters or official documents.

At that time, the term “papal bull” included many things: encyclicals, decrees, notices, and pronouncements of all types. The earliest were written on very large sheets of papyrus, though smaller copies were often made on parchment. A French writer of the tenth century, speaking of a privilege obtained from Pope Benedict VII (975–984 A.D.), says that the petitioner who went to Rome obtained a decree duly expedited and ratified by apostolic authority; two copies of which, one on parchment, the other on papyrus, he deposited in the archives on his return.12

It boggles the mind to think that papyrus, the sacred reed of the pagan Egyptians, was now equally blessed and revered by the Catholic Church. And it remained special until the ink dried on the last bull known to have been written on papyrus in 1083 A.D., the Typikon of Gregory Pakourianos, the noted Byzantine politician, military commander and patron of the Chuch. By then, Europe had turned to parchment for its needs and the church followed suit. Thus, in the late twelfth century, Eustathius of Thessalonica complained of the “recent” disappearance of papyrus.13

In the Muslim East, improved forms of rag-pulp paper eventually became the preferred medium, thanks to fact that it had a more uniform surface, could be written on both sides, and more easily made into a book, so that the last Arabic document on papyrus in 1087 A.D. existed side by side with Arabic manuscripts on laid paper that survived into the eleventh century.14