At the meeting it was obvious they were suspicious. The Egyptians had never met anyone like Thor Heyerdahl before, and it wasn’t because he was Norwegian; his companion at the talks, Peter Ankar, the Norwegian ambassador to Egypt, was well-liked and easy to fathom. Perhaps it was because it was a hectic time in Egypt. The 1969 War of Attrition was in progress. At the bottom of the steps of the government building in which they were meeting, a barricade had been erected, characteristic of wartime Cairo, with sandbags stacked in front of all the windows.

Egypt was mounting a springtime offensive in the Suez. Large-scale shelling was going on along the Suez Canal, extensive aerial warfare and commando raids were in progress daily, which meant perhaps that they were at a point where they might need friends, and another Scandinavian might help, much like Gunnar Jarring the Swedish diplomat who had been charged by the United Nations to find peace that year in the Middle East. At least they knew where Peter and Gunnar stood, unlike this whacky Norwegian archaeologist.

“You want to rope off a bit of desert behind the Khufu Pyramid to build a papyrus boat?” the thickset Egyptian minister asked in disbelief. He adjusted his horn-rimmed glasses and looked at Thor with a questioning smile. He glanced half dubiously at Ankar who politely smiled back as he stood erect and white-haired beside Thor, as “a sort of pledge that this stranger from the north was in his right mind.”1

Thor was asking to violate the sacred ground on which stood the tombs of the pyramid builders, a place that according to Zahi Hawass was protected by a curse. “O all people who enter this tomb, who will make evil against this tomb . . . May the crocodile be against them on water, and snakes against them on land.”2

Mohammed Ibrahim, Egypt’s director of antiquities, died in 1966. His successor Gamal Mehrez, director of antiquities who was present at the meeting, had been plagued with dreams of death, and then while going to a meeting in Cairo on King Tut’s treasure, he was hit by a car and died instantly. Three years after Mehrez’s meeting with Heyerdahl and Ankar, during a loan of King Tut’s death mask to London in 1972, Mehrez himself slumped to the floor dead at fifty from circulatory collapse.

Thor was asking permission from people with such memories and fears fresh in their minds. They finally agreed to allow him to cordon off an area and set up a tent, a camp, and a boat-building site, but only if he swore that he would not dig in the sand.

Present at the meeting was a man in his late fifties, Hassan Ragab. Early photos show him as a handsome young Basil Rathbone type, with a dark, clipped military moustache that turned gray in later life. Ragab had brought cuttings of papyrus back from Sudan and established plantations and an institute in Cairo where he made papyrus paper for the tourist trade. At the meeting he was the most qualified to judge Thor’s project. Would it work? Would it sink? If so, how would that reflect on Egypt? It was, after all, a very public undertaking, and while the boat was being built, tourists would be visiting the site, which lay near the Khufu’s Royal Boat Restoration project close by to the pyramids.

Like the other high-ranking Egyptians, Ragab was suspicious at first. In the papyrus plantations that he had started on the Nile, he knew that if fresh green stems were cut and tied into large bundles, they would be very heavy. A boat made of that may not sink, but it would not float easily. Thor explained that he was not talking about using green stems; he would use dry stems in which air could be trapped when they were tied tightly together in bundles. He had done a great deal of research on reed boats and knew it could be done. Ragab, an engineer as well as a diplomat and military man, was satisfied and Thor’s project went forward, but perhaps Ragab learned something else at that meeting besides the basics of reed boat construction. He was good at book learning and admired academia, but it must have been obvious to him that he had just received a lesson in public relations from a master.

If you are going to deliberately attempt to manage the public’s perception of a subject, this was the way to start. Thor had used the meeting to good effect. The day he set foot on the sacred ground of the pharaohs the fame and press coverage would begin, and the minute he announced that he was having tons of papyrus shipped from Lake Tana in Ethiopia to Cairo it would be news. Why? Because papyrus had not grown in Egypt for over a thousand years? Or was it because a papyrus boat had not sailed on the Nile for twice as long? Or was it simply because papyrus, plant of ancient days, was again playing a crucial role?

Whatever it was, Ragab saw the cameras clicking and whirring, and he realized as a result that the plant that he had fallen in love with was again on the front pages of the world press because of this Norwegian. It was a lesson he would never forget.

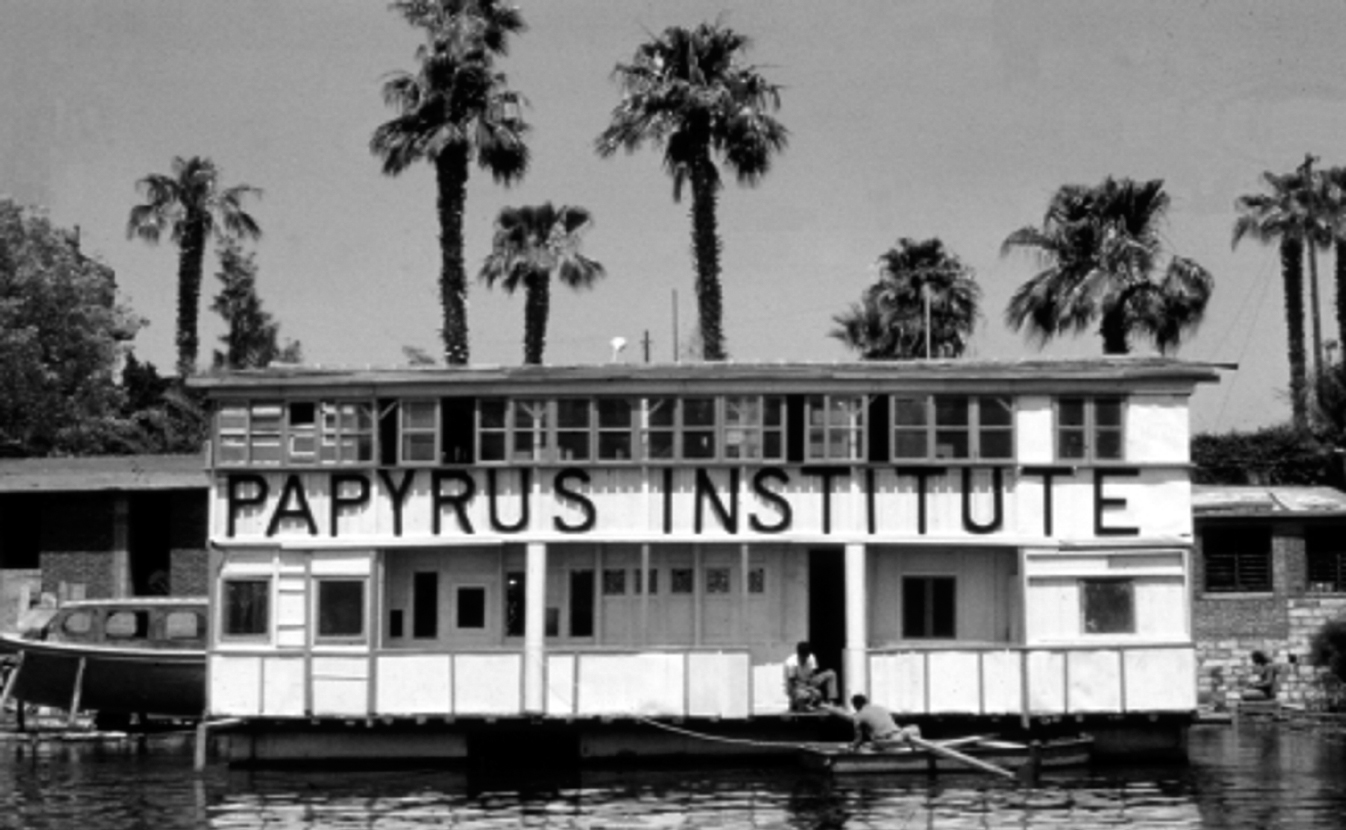

A former engineer, general in the Egyptian Army, cabinet minister, and ambassador to China, Italy, and Yugoslavia, Hassan Ragab had by then retired from active government service, and the previous year had founded his institute in Cairo devoted to the history and manufacture of papyrus paper. He called it the Papyrus Institute and he eventually came to know practically everything about papyrus that could be known. While in China as ambassador, he had seen a small family operation where laid-pulp paper was manufactured by hand, a process not very different from the method used 2,000 years earlier during the period when China invented the process of modern paper production. That gave him the idea. “It occurred to me,” he said, “that if we could set up something like that in Egypt, perhaps it might become another tourist attraction.”

Hassan Ragab’s original Papyrus Institute, a houseboat on the Nile, 1973.

He went on to do a great deal of research into the ancient methods of papyrus papermaking and in 1979, earned a PhD from Grenoble in the art and science of making papyrus paper; meanwhile he also cultivated more cuttings of papyrus from the plants he had brought from Sudan and expanded his plantations in shallow, protected areas of the Nile River.

He died in 2004 at age ninety-one, but by then his plant cuttings and papyrus paper initiative had evolved into a modern industry. Today in Cairo, Luxor, and the delta thousands of sheets are made and sold to tourists, a production similar to that of ancient days when Egypt was the major center for the production of papyrus paper in the civilized world.

Ragab was a great believer in making museums “come alive.” We first met in 1973 when I was on tour in Egypt; by then his papyrus paper project was just beginning to turn a profit and he looked forward to expanding the Institute. His goal was to create a “living museum,” a concept that was all the rage then. The major museums of the world in the seventies were in a terrific hurry to jump on the same bandwagon. I imagine it was, and still is, difficult for museums to come up with innovative exhibits, though they’ve made great strides: witness the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Smithsonian museums in Washington, the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert in London, and the Louvre in Paris. They go to extraordinary lengths to breathe life into the past. And the new museums—the Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Museum of the American Indian, and the Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington—are all designed from the beginning to address the issue of “living history.” This is obviously the way of the future.

“For me Williamsburg still has the edge,” Ragab said, referring to the trade and small industry boutiques at America’s largest showplace of living history. “I want to transport the viewer back into an ancient world and to allow them to mingle with the craftsmen, let them look over the shoulders of the ancients to see how they did things. You Americans are good at that.” In his new facility he decided that everything must be there, “From Pharaoh on down, the papermakers, scribes, weavers, potters, artists, all in their proper place.”

Around the time I first met Hassan, there was already talk about re-creating the great Royal Library of ancient times in Alexandria. The new library was finally built and dedicated in 2002 at a cost of $176 million with the support of many nations. Dr. Ismail Serageldin, a former vice president of the World Bank and an accomplished writer in economic development and biotechnology, was appointed its first director.

The library’s design features a cylindrical building, set in a pool quite near the sea and a gridded glass roof sloped downward until part of it disappears below ground level. A spectacular structure, it accommodates an ambitious international program, including a library that can hold millions of books; specialized libraries, conference centers, and research facilities to restore manuscripts. The library also serves as one of the external backup archives for the global Internet. As part of a joint program with the Internet Archive, the library received a donation of five million dollars and a collection that includes: 10 billion web pages spanning the years 1996–2001 from over 16 million different sites; 2000 hours of Egyptian and U.S. television broadcast archives; 1000 archival films; 100 terabytes of data stored on 200 computers.

The new Library in Alexandria (Wikipedia).

It should be noted that the new facility was built from scratch using modern ideas and concepts, since we have no idea of what the original looked like. But now because of advances in 3-D imagery and digital reproduction, existing documents, antiquities, and even buildings, no matter how large or small, can be replicated almost exactly.

A case in point are the tombs of Egypt. Sharon Waxman in her 2008 book Loot remarked on the tomb of Seti I in the Valley of the Kings—a marvelous, incomparable work of art, with its twenty-foot ceiling and bright colored wall paintings—but it is not an easy place to get to and today it is closed to the public because of the risk of damage to the artwork.3 No one can see or photograph it, except by special permission. Waxman pointed out that after it was discovered by Giovanni Belzoni in the early 1800s, he had the bright idea of re-creating the rooms and putting them on display. He hired an Italian artist to make wax models that could be reconstructed as full-scale models in London. “He opened it as a tourist attraction and business endeavor in 1821 at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly and charged an entrance fee. The exhibit was such a hit that it lasted a full year. It is worth considering in our age of modern technology. Can’t we build a replica and invite everyone in? Constructing the same sort of model today would be easier and more faithful to the original. It would open up access to the wonders of ancient Egypt and could travel the world or sit permanently near the Valley of the Kings. In short, perhaps Seti could be brought to the people if the people cannot be brought to Seti.”

Thankfully, someone is listening. Adam Lowe, a former painter who runs the Madrid-based restoration workshop, Factum Arte, built a replica of King Tut’s tomb in Egypt, which according to Daniel Zalewski, features director of the New Yorker, was the most heralded digital facsimile yet made.4 Lowe now intends to take on a replica of Seti I’s tomb.

Hassan Ragab was enthralled with the idea that the Alexandria Library would be rebuilt. “That library, as you may remember, held hundreds of thousands of volumes of papyri—until Julius Caesar burned them. We can’t restore all of them, but there are more than 40,000 papyri still in existence today (under glass or in storage) and once we can get some of the originals and copies of others under one roof, we’ll have a nucleus. That assumes, of course, that by then we will have begun to make papyrus on a large enough scale—and we will, we will.”

That was in 1973, and back then it was only a dream; now in the twenty-first century it could become a reality. The days are gone when the papyrus plant was lacking and technicians nonexistent: the papyrus papermakers in Cairo now have the means and the skills. A good example of what could be done at the village level is the story of papermaking in the delta, where papyrus plantations on a 500-acre swampy plot were established in the seventies by Dr. Anas Mostafa. Dr. Mostafa trained 200 villagers in the cultivation of the plant and the ancient method of papermaking. At the height of the tourist market early in this millennium thousands of sheets of papyrus paper were being made here. There is also a capability for illustrating papyrus sheets with silk screening, 5,000 sheets per week can be done.5 What is needed is a link between the papermakers, the library, and the museum world, and a global effort to re-create in major museums what the world of scrolls looked like.

The papermakers and artists are ready, willing, and capable of re-creating a large enough number of scrolls to allow at least one corner of any major library to be used to play out the ancient drama of papyrus paper in the time of the Ptolemies.

Such an exhibit could also re-create the environment of an early age with readers, researchers, and thinkers wandering in and out of the facility, with ready access to real scrolls of papyrus paper inscribed with the classics that could be rolled and unrolled with impunity. The touristic possibilities of such an exhibit are impressive.

Aside from the re-creation of such a library of scrolls and bringing back to life the world of ancient scholars, another benefit of the papermaking industry in Egypt would be the replication in a detailed manner of special scrolls, such as the case in 1989 when the McClung Museum at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville commissioned an exact replica of the first three feet of an original papyrus scroll, the Papyrus of Kha. This papyrus is an edition of the Book of the Dead similar to Ani’s Papyrus, and was likewise found in Thebes. It belonged to the ancient builder, Kha and his wife Merit and is dated 1386–1349 B.C. It was 52½ feet long and is today in the Museo Egizio in Turin. The replica depicts the deceased Kha and his wife before the great god of the dead, Osiris, and, according to Evans “in twenty years the colors of the replica have not faded and the papyrus copy is still in excellent condition.” The facsimile was done by Antonio Basile, of the Museo Didattico del Libro Antico in Tivoli, Italy. Antonio is the brother of Corrado Basile, the founder of the Instituto di Papyri in Sicily, one of the few places outside of Africa where papyrus grows naturally. Corrado, a pioneer in the restoration, repair and re-creation of antique papyrus paper has worked with the Egyptian Museum and the International Papyrus Institute in Cairo. His goal is to help restore the 30,000 ancient papyri in the museum’s collection.

Luckily the technique for creating facsimiles has grown by quantum leaps with the introduction of digital methods. The newest techniques avoid the problem of replicas painted by hand, which record only the details that the copyists notice; they have no scholarly value. Also helpful is the fact that several photographic facsimiles of the Ani Papyrus have been available for many years on paper. The first appeared in a British Museum edition in 1890, the latest was printed in 1978 by ADEVA (Akademische Druck-u. Verlagsanstalt, Graz, Austria) on thirty-seven pages. A more sophisticated edition appeared in 2018, produced by CM Editores in Salamanca, Spain. This latest facsimile is an expensive limited edition of 999 copies made from the original color photos and printed on modern papyrus paper on thirty-seven pages. One drawback of all of these facsimiles is that they represent thirty-seven separate sheets rather than a complete scroll. Perhaps it would be possible using techniques devised by Adam Lowe to print an entire seventy-eight foot scroll intact. In replicating the King Tut tomb, for example, he used a very accurate “warts and all” method that involved modifying an enormous Epson printer so that it could make repeated passes over a gesso-like skin in perfect registration. The skin was then put in place on walls built for the purpose in Luxor. Lowe is also unusual in that he makes a great effort to incorporate Egyptian personnel and facilities into the project. He is training Egyptians in his scanning methods in his Madrid workshop, and plans to set up a digital-fabrication studio in Luxor. The moment is approaching where a facsimile of the complete seventy-eight-foot roll of Ani’s original book can be printed on native papyrus paper by Egyptians, much like Ani’s team of scribes did when they produced the original over 3000 years ago.

The immediate goal of such an initiative would be to supplement the exhibit of ancient scrolls visualized by Ragab for the Alexandria Library, or a similar collection in the Getty Villa dei Papyri, or any other museum interested in the history of ancient Rome or Egypt. In addition to a collection of scrolls similar to those in the ancient libraries, a mobile exhibit could be mounted that would use the new Egyptian-made scrolls to be placed inside of, or attached to, a flexible plastic medium. This would allow them to be used in a free-form manner inside any viewing space and would get away from the large problem of having to display such documents on a wall. Often a bare wall is a rare and most coveted item in a modern museum.

Rolled in part or whole, it would also show the public what scrolls are all about, much like the case of the Bayeux Tapestry and the British facsimile that has been on view since 1895 in Reading. It could be an effort equivalent to Heyerdahl’s highly publicized Ra project where he produced a replica of a papyrus boat, but this time the project would feature the return of the ancient papyrus paper industry to Egypt. Egyptologists from all over the world could be involved, assisted by a multinational team of experts who would simulate not just the effects of ancient Egyptians on the people of other lands, but the world of papyrus paper from the time of the New Kingdom until the time of the Roman and Islamic Empires, when papyrus paper was the principle medium in use.

Another advantage of the techniques used by Lowe in Egypt is that facsimile scrolls could be made in multiple copies, enough to use in any available space in the old or new Cairo museums, as well as in national museums in countries worldwide. A flexible medium would allow the scroll to be “free formed,” or wrapped around or through any collection. It could be paired with smaller “living” mini-exhibits, as in the new museums, or, in a darkened room it could be highlighted with sequential spotlights in a mini sound and light show. The possibilities are endless.

Papyrus-making crafts, papermaking, the history of writing, art, manuscript illumination, restoration and research on ancient papyrus scrolls, along with hands-on and visitor involvement activities, and so on, could all be put in place and supplemented with some or all of the thirty-seven panels of the original Ani scroll on loan from London to Cairo or elsewhere. The originals could finally be taken out of storage and shared out and incorporated into the “living” exhibits from the start. The intention would be to have the original scroll become a useful resource for participating museums in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and the Americas.

Other centers of Egyptology would be encouraged to join in; France, the United States, Germany, Italy, Austria, and the United Kingdom could participate in the program by duplicating or borrowing the exhibit on their own as they wished. The Papyrus of Ani would be ideal for this as it is one of humanity’s earliest and finest spiritual treasures. The exhibit would highlight the papyrus paper industry, explaining and reliving its history and illustrating how it affected the world in the way that Marshall McLuhan imagined, where the form of the message determined the ways in which that message was perceived. In the ancient days of papyrus paper, the scroll had far-reaching sociological, aesthetic, and philosophical consequences, to the point of actually altering the ways in which the ancients experienced the world, just as later papyrus pages in the form of a codex influenced the Christian world. In the case of papyrus, the medium was the message, and it was a medium that changed the way people lived their lives and went to their deaths.

That is the story that would be illustrated by the Papyrus of Ani, and shared not just by Egypt and England, but by the world. In the process, Wallis Budge might even be pardoned, forgiven and possibly even thanked, for starting something he never intended.

The way ahead was illustrated to me one day in New York. I had a few hours to kill, the Metropolitan Museum was close by, and so I decided once again to visit the Egyptian Great Hall, which is always a treat. Once through the hall, I started through the galleries and caught myself thinking what a shame when I saw the large colorful Egyptian frescoes lining the walls.

Having just read Brian Fagan’s The Rape of the Nile, I recoiled at the thought that someone had cut these wondrous works off the walls of Egyptian tombs. Even though they were well mounted and obviously cared for, like Vivant Denon, I felt the gall rising as I thought of the crime involved. Then at the end of the gallery before passing on, my eye caught a small sign that read Facsimile Wall Paintings.

I stopped cold in my tracks. Facsimile! I couldn’t believe it. But after going back and looking as closely as I could, without arousing the suspicions of the guards, I had to concede there wasn’t a piece of purloined plaster in sight.

They were drawings on paper!

Did any of my fellow viewers notice? Were they disturbed by the fact that these were facsimiles? As far as I could tell there wasn’t a jaundiced eye in the house. For the next ten minutes as I watched hundreds streaming by (the gallery is on the way to many other exciting displays), I saw quite a few pass with only a glance or two, but many stopped, looked and snapped photos, some sat and consulted their printed guides, and some sat and admired the paintings with satisfied looks on their faces.

I realized then that it was an extraordinary exhibit, and, despite my ill-founded suspicions, to all intents it was the real thing.

How was this done? It turns out that the story behind the Facsimile Collection of the Met is as exciting as the collection itself. It begins with the artist couple, Norman and Nina de Garis Davies, already in residence in Egypt when they were joined by a third artist, Charles Wilkinson, who later became an emeritus curator. A student of the Slade School in England, Wilkinson was recommended because of his abilities in tempera painting. Also, as he noted in one of his books, active service in WWI had left him, at twenty-two, “none too strong physically.” It was felt that “the climate of Egypt would do him good.” It must have helped, as he lived to be the last surviving member of the expedition and died at age eighty-eight.

Once the museum’s Egyptian Expedition had been granted a concession to work in the tombs at Thebes on the west bank of the Nile opposite Luxor, all three settled down to work in the early 1900s. One problem that arose immediately was that permanent, accurate copies of the wall drawings could not be easily done. Existing photographic means were inadequate. Photos alone would have been too artificial. Neither would watercolor sketches do, as existing pigments were too transparent. The solution was found by Francis Unwin, Norman’s assistant, who discovered that egg tempera would closely duplicate the original earth colors of the ancient paintings.

I realized later that this was the reason I was taken in. I had grown too used to the fake colors used in gaudy copies on postcards, and now on the Internet, which led me to reject reproductions. Having seen original paintings in Egypt, I thought I knew the real thing on sight. It turns out in this case that it wasn’t only the paint that did the trick; it was the skill of the artists.

We have one description from Nigel Strudwick, a specialist in Egyptian art at the University of Memphis on how it was done. When, for example, Nina was “painting a male figure wearing a white robe through which the body color is partially visible, she would paint the background, apply a solid area of color for the body, overlay it with the white for the robe, and draw the red-brown outline, cleaning the figure up, as had the ancient painter, by application of further background color.”

She also developed a way of including damaged sections by painting them in. She did this in such a way that it captured the texture and the composition of the gaps and holes. Even the cracks in the original wall that are so common to the original wall paintings were carefully rendered, so much so that they seem three-dimensional. The result of their effort is a collection of 350 wall drawings in the Metropolitan, all of which are valuable records. In those cases where the originals have disappeared, from one cause or another, the drawings have become priceless as the only remaining record. In sum, the de Garis Davies had made an elegant case for facsimile tomb paintings. Recently the same case was made for ancient papyrus paper when the new Museum of the Bible opened in Washington, DC.

It was at this time I decided to leave aside the complexities of exhibiting very long rolls of papyrus paper and turn my attention to the single sheets found in ancient letters and early codices. Here I struck gold. The Museum of the Bible had opened to great fanfare in Washington, DC, in 2017 and, I thought, this was only right as, after all, the Bible as a subject of historical research has to be a crowd-pleaser. Even more interesting was the media reaction, in which this museum was said to be “the most technologically advanced museum in the world, offering an unbeatable combination of interactive entertainment, scholarly investigation, and historical exhibition.”6 The Washington Post declared that it would “set a new standard for how this country’s museums fuse entertainment and education,” and it does so “in a way that many visitors will probably find more compelling and accessible than the dense cultural stew on view at the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History.”7 The Post also pointed out that the museum uses the “master narrative” idea of history, “that there is one sweeping human story that needs to be told, a story that is still unfolding and carrying us along with it . . . It is an exciting idea, and an enormously powerful tool for making sense of the world.”

I was encouraged to think that this museum was the answer to my prayers since, if there were any place that papyrus paper would be taken seriously, it would be here. Obviously there has been so much original material lost over the last two thousand years that it makes the remaining fragments and pages of papyrus relating to the early Christians rare and very valuable. Proof came as I passed through the pair of awe-inspiring forty-foot bronze panels inscribed with Genesis 1 that flank the front entrance. Immediately inside the vestibule, I saw an illuminated blow-up of some papyrus paper pages. Several large glass panels were in place showing Psalm 19 from the Bodmer Psalter, an ancient papyrus prayer book used by third century A.D. Christians. This is a psalter the publication of which in 1967, according to Professor Albert Pietersma of the University of Toronto, was nothing short of sensational for scholars interested in such things. Not only is this manuscript the most extensive papyrus of its kind discovered to date, but its text, even apart from its immense value for the reconstruction of the Old Greek, presents us with a Greek psalter as it was used in Upper Egypt in ancient days.

Further along on the third floor, I was pleasantly surprised to see the extensive use of papyrus facsimiles in the museum’s permanent exhibit called, History of the Bible. On display were eleven original ancient papyrus pages or fragments including five pages of the famous Bodmer Psalter. Alongside these were seven facsimile items including an eleven-page facsimile codex, all of which fitted seamlessly into the story that was being told.

An important point made by Professor Pietersma was that scholars such as those using the museum’s facilities, are much indebted to various editors and the Bodmer Library who have helped in the production and circulation of complete and excellent facsimiles, since this “enables one to obtain first-hand information and to correct the edited text where necessary. It also makes it possible to reassess the restorations compiled by editors which, upon reexamination, can sometimes be improved upon.”8

Under the soft lighting in this special room, a room devoted to the earliest part of Bible history, we can almost hear the Christian copyists scratching out the Word and calling out for fresh pages of paper—papyrus paper—as they press forward on their pathway to glory.