Chapter 2

Aging, Programmed Longevity, and Juventology

Why We Age

The approach in this book is different from that of the great majority of nutrition books because I focus on keeping organisms young, not treating individual diseases or conditions. So it’s important to understand what aging is and the strategies that have the best chance of slowing it down without causing side effects.

“Aging” refers to the changes that occur over time to both organisms and objects. These changes aren’t necessarily negative. In fact, although humans and most other organisms become dysfunctional in old age, growing older can actually bring improvements as well. For example, New York marathon winners are typically in their thirties, and many of the top finishers are in their forties. This suggests that there can be overall positive changes in the human body associated with aging.

So why do we age? Clearly every object around us, from houses to cars, gets old and deteriorates, so perhaps a better question is this: Why wouldn’t humans and all other organisms also age and die?

Natural selection, the process Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace described to explain evolution, has resulted in mechanisms that protect an organism, such as DNA repair, until it can generate healthy offspring. Over millions of years of evolution, the lifespan of an organism will tend to get longer if its ability to generate healthy offspring also increases. Both Wallace and Darwin also hypothesized that aging and death may be programmed so that organisms could age on purpose and die prematurely if it were advantageous to the species—to avoid overcrowding, for example. You can think of it like a company that establishes mandatory retirement at age sixty-five in order to allow younger employees to be hired, with the idea that ultimately this benefits the company. Both scientists abandoned this theory because, at the time, it would have been extremely difficult to demonstrate, since they did not have the computational, molecular biology, and genetics tools we have now.

A century and a half later, my laboratory produced one of the first pieces of experimental evidence for this “programmed aging” hypothesis. We showed that a selfish group of microorganisms—in this case baker’s yeast that had been genetically manipulated to invest in their own protection and live as long as possible—would eventually become extinct, whereas shorter-lived microorganisms willing to sacrifice themselves and die early would seed future generations. In other words, the genetic alterations that make the organism act selfishly and live longer decrease its chances of generating healthy offspring. Whether human beings are actually programmed to die, however, has not been demonstrated.

To fully demonstrate programmed aging, one must first demonstrate group selection—one of the most hotly debated and challenged theories of evolutionary biology. Group selection posits that groups of organisms can act in an altruistic way, to protect or benefit the group at the individual’s expense.

In most cases, it can be argued that altruistic behavior—a bird flying in front of the flock, for instance, thereby taking additional risks for the sake of the group—is just a case of paying one’s dues, and that the risk taken will eventually benefit the individual taking the risk. But when an organism dies to benefit others, it’s impossible to deem it a selfish act. Either death is occurring by chance (i.e., it serves no purpose), or it’s programmed and altruistic. Over the past ten years, I have argued for programmed aging in a series of public debates against experts who argued for traditional evolutionary aging theories. After two such debates, in Texas and California, the audience, made up of scientists, was asked to vote on the theory that seemed right. In both cases I lost, though the vote and following discussions suggested I had convinced nearly half of them. Why? I believe it’s because current evolutionary theories are accepted as dogma, and most scientists just aren’t willing to consider alternative possibilities. To maximize the chance for everyone to make it to 110 healthy, it is important to consider these evolutionary theories and take advantage of the programs that have evolved to extend longevity in response to changes in the environment. For example, we showed that the “altruistic death program” described above is inactivated by starvation, indicating that an organism left without food no longer dies to benefit others, probably because the others are not expected to be around to benefit.

There are hundreds of theories of how and why we age. Many are partially true and overlap. For example, the popular free radical theory of aging I already mentioned proposes that oxygen and other reactive molecules that function as oxidants can cause damage to virtually all components of a cell and organism, similar to the rusting of metals when exposed to oxygen and water. Tom Kirkwood’s “disposable soma” theory is another well-received theory of aging. It proposes that organisms invest in reproduction, in offspring and in themselves, but only to the level necessary to generate healthy offspring. The soma, our body—which is the carrier of the genetic material contained in our sperm cells and oocytes—is therefore disposable once it has generated a sufficient number of offspring. Unflattering as it sounds, under this theory we are merely disposable carriers of DNA.

Because these theories focus on the aging process and not on the potential for organisms to stay young, fifteen years ago I came up with my own explanation of aging: the “programmed longevity” theory.1 I proposed that an organism could, in fact, afford a greater investment in self-protection against aging, and that this could have important implications for human life and the prevention of diseases; since by altering the “longevity program,” we could postpone the age at which we begin to become frail and sick. Imagine, for example, moving this age from fifty to seventy. If this is possible, you might wonder, then why did this longevity program ever become dormant?

The answer is not that it is impossible to maximize both protection and reproduction, but that the level of current protection is sufficient to carry out the task. The other reason for the program to have remained dormant is that historically we reproduced, or tried to reproduce, much more frequently than we do now. So for the great majority of human history, activating a program that reroutes so much energy away from reproduction to use for protection and repair would not have been advantageous.

Consider this analogy: Would it be possible to build a plane that could fly years longer than current models without its performance suffering?

The answer is yes. There are at least two ways to accomplish this:

- The longer-lived plane would need more fuel and more maintenance for each mile it flies to prevent damage.

- The longer-lived plane would require superior technology to reduce damage while using the same amount of fuel and maintenance as current models.

Now let’s apply this to humans:

- People who live longer would need more energy to perform more maintenance (DNA repair, cellular regeneration, etc.).

- People who live longer would need to get better at utilizing energy to increase protection against aging and maintaining normal function for longer.

However, there may be no evolutionary reason to do it, because for the human species to continue to thrive, aging and death at eighty is perfectly acceptable. But what if we wanted to be just a little more selfish and live an extra thirty healthy years? Is it possible to improve the protection and repair systems to stay young longer, or even become younger? Or have we reached a maximum level of protection?

I believe, and the data indicate, that we have not—that it is indeed possible to improve the body’s protective systems or make these systems continue to work longer so that we undergo decline and begin to encounter diseases not at age forty to fifty but at age sixty to seventy or better yet, never encounter many of them at all. In the following chapters I will show how genetic or dietary interventions can not only delay diseases but actually eliminate a major portion of chronic diseases in mice, monkeys, and even humans to extend longevity. At the foundation of these effects is what I called programmed longevity: a biological strategy to influence longevity and health through cellular protection and regeneration to stay younger longer.

Juventology

Discussions about theories of aging are great entertainment for scientists but not much use to anyone else. Under the programmed longevity theory, how and why we age is not as interesting as how we stay young. Because of the importance of this distinction, I coined a term for this area of inquiry: “juventology,” the study of youth. What’s the difference? A great deal.

If you are trying to understand why a car ages, you might study the engine and conclude that over time it slowly rusts. To make it last longer, you might add an antioxidant additive to the fuel or motor oil. This is essentially what the free radical theory of aging supports as a way to extend healthy longevity. But this is like what I said before about vitamin C and the Mozart symphony: you can’t improve Mozart’s compositions by just adding cellos—you have to write a better symphony. But for the sake of argument, let’s suppose that you could slow the aging of the engine a little by adding a lot of antioxidants. This aging process and the small effect of the antioxidants on it becomes irrelevant, however, if the owner of the car rebuilds the engine every ten years, replacing the damaged parts with brand-new ones.

The same applies to the human body: we can try to understand how it ages and attempt to slow that down, or we can identify ways to eliminate aged components and periodically replace them with young ones. In this case, it doesn’t matter how the body ages, whether by oxidation or some other mechanism. The goal changes from protecting the body from damage to improving protection and, more importantly, repair and replacement/regeneration.

In both cases the body ages with time, but if we can program health to last longer, the system will trigger protection, repair, and replacement mechanisms to maintain the organism’s vigor and functionality. This is the difference between the current gerontology/aging-based approach and what I think is a more effective juventology-based approach. It is worth keeping in mind that protecting the body from aging and damage is also important because we are a long way from being able to repair and replace molecules, cells, and systems perfectly. Thus, combining the gerontology and juventology approaches is ideal.

Throughout this book, I will describe specific dietary changes that have protective, regenerating, and rejuvenating effects. As my laboratory has discovered, there is a clear connection between nutrients and longevity genes, which can be activated to promote cellular reprogramming and regeneration so that an organism can stay healthy longer and, as a consequence, maximize what we call “healthspan,” or healthy lifespan.

The Discovery of the Aging Genes and Networks

To keep organisms young, we must “reprogram” the “youth period” from a forty-to-fifty-year length to a sixty-to-seventy-year program or longer. To learn how to reprogram longevity though, I had to better understand its molecular mechanisms. The dietary interventions described later in the book are based on discoveries made in part by my laboratory’s research into just this.

In 1992, I came to UCLA, at that time one of the world’s leading centers of longevity research, to devote myself to the genetics and biochemistry of longevity. I had put my career as a rock guitarist on hold, though I did perform in Los Angeles and toured on the West Coast during my first three years of graduate school. Perhaps influenced by the Hollywood obsession with staying eternally young, each of the two rival research universities of the City of Angels had attracted its own master in the field of aging: famous pathologist Roy Walford was at UCLA, and renowned neurobiologist Caleb Finch was at USC.

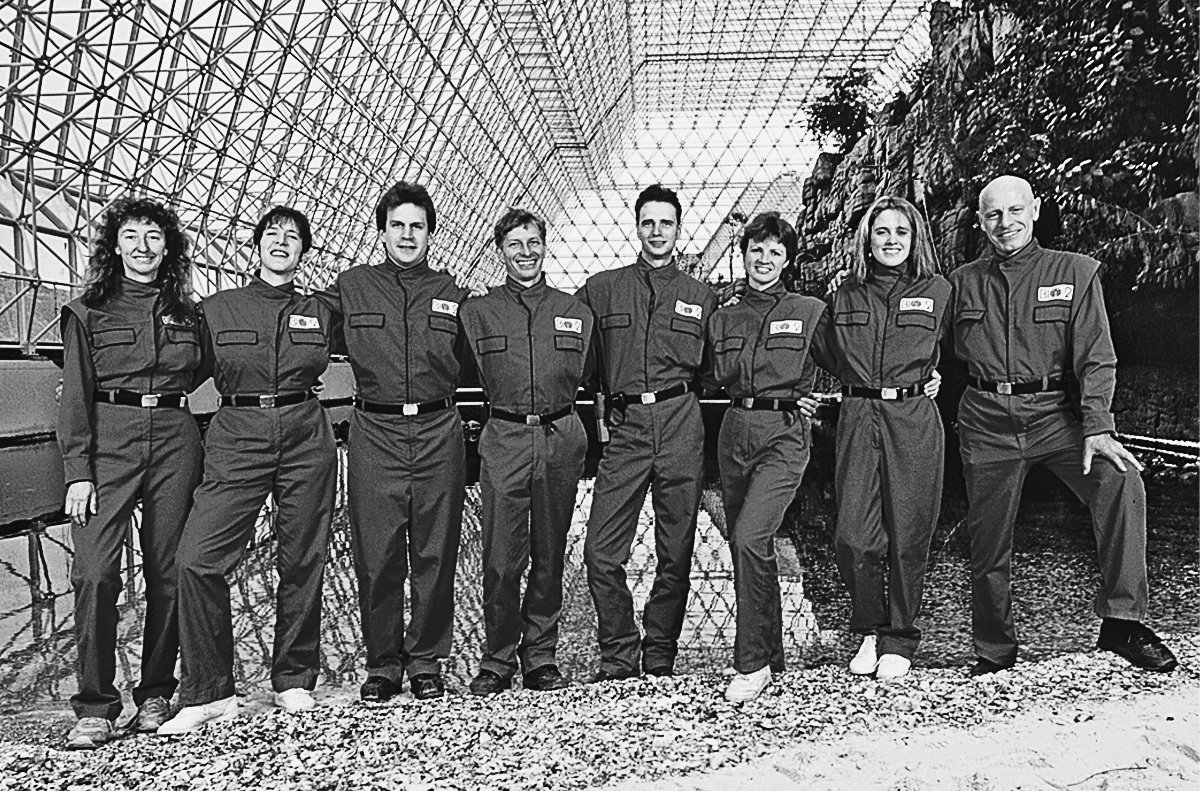

I elected to join Walford’s group for my doctoral work. Under his watch, I studied the effect of caloric restriction—how reducing the daily calories consumed by mice and men by 30 percent every day affects their aging and lifespan. However, Roy and I spoke only via video conference because he had decided to lock himself away for two years, along with seven other people, in a sealed environment in the middle of the Arizona desert. Called Biosphere 2, this self-imposed exile was an experiment to understand whether and how humans could survive in a completely sealed environment, producing all the food they needed: a useful experiment in the responses of humans to a highly regulated environment with possible applications for living on space stations. I went to Arizona at the end of the two years to welcome the eight adventurers as they came out of Biosphere 2. As part of the experiment, they had been calorie restricted and consumed very few calories a day for two years. When they emerged at the end of it, they were extremely thin and looked angry.

After being in Walford’s UCLA lab for two years, I still had little insight into the secrets of aging. Mice were too complex to allow rapid identification of the genes that regulate and affect aging. Also seeing the angry faces of the Biospherians made me think that there must be a better way than chronic calorie restriction to delay aging, and I was impatient to find it. It prompted me to move to the biochemistry department, and the laboratory of Joan Valentine and Edith Gralla, to study aging in baker’s yeast: a simple unicellular organism that allowed me to study the molecular foundation for life, aging, and death.

We think of yeast as an ingredient in bread and beer, but Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker’s yeast) is in fact one of the most studied organisms in science. This single-cell organism is inexpensive to work with and easy to study. It is so easy to work with that some scientists carry out yeast experiments at home. It’s also easy to modify genetically, by simply removing or adding one or more of its roughly six thousand genes.

2.1. Roy Walford (far right) and the Biospherians at the beginning of the experiment, 1991

A small group of scientists, including myself at UCLA and Brian Kennedy at MIT, decided the easiest way to understand how humans age is to identify the genes that regulate the aging of simple organisms, like yeast, and eventually move back to mice and humans. There was a big risk, however: What if our discoveries about how yeast ages had no relevance to humans? Most scientists studying aging in mice and humans had assumed that to be the case and were not that interested in our research on these very simple organisms.

But I had faith it would work and was determined to try; the risk was big but the potential payoff—figuring out the molecular mechanisms of aging—was worth it. My first step was to define a new scientific approach to studying aging. Because aging in yeast was studied only by a method called “replicative aging,” which would be equivalent to studying human aging by determining the maximum number of children a woman could have, I developed a method called “yeast chronological life” and used it to identify a set of genes important to aging. This method allowed me to measure aging chronologically—in other words, the same way we measure it for humans or mice—by being able to monitor every few days how many of these microorganisms remained alive. It was 1994, and no one had ever identified a gene that regulated the aging process in any organism. Thanks to the work of Thomas Johnson at the University of Colorado and Cynthia Kenyon at UC San Francisco, it was known that genes could make worms live longer—just not what genes they were or how they worked.

With three Nobel laureates and seven members of the National Academy of Sciences in the pharmacology and biochemistry departments, UCLA was science heaven. I was surrounded by great geneticists, biochemists, and molecular biologists, all ready to help. I didn’t even have to knock, because the doors—even those of the Nobelists—were almost always open.

Even so, we didn’t tell people we were working on aging. Although within ten to fifteen years the field would explode, back then it was considered a strange, even crazy area of study, and we were considered an odd group. When people asked what I was working on, I would say, “Free radical biochemistry.”

After just one year I made two important discoveries using the method I had invented:

- If I starved yeast—by removing all the nutrients available to them and giving them only water—they lived twice as long.

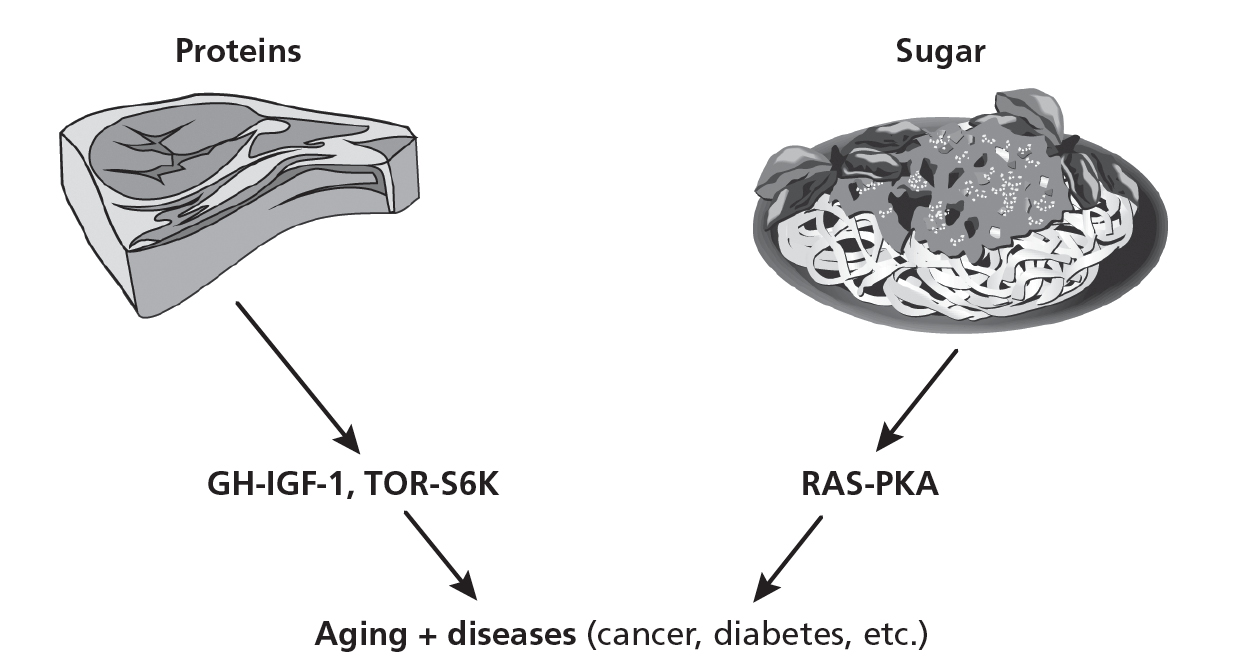

- Sugar is one of the nutrients responsible for yeast aging fast and dying early. It activates two genes, RAS and PKA, that are known to accelerate aging, and it inactivates factors and enzymes that protect against oxidation and other types of damage.

In a short period in the biochemistry department, I had identified not only the first gene regulating the aging process but also the entire signaling pathway, all thanks to a very simple organism.

The system was so simple and so new that the scientific community was in disbelief and struggled to understand, let alone accept, the chronological aging system and the discovery of the pro-aging sugar pathway. Leading science journals refused to publish the findings my mentors and I found so extraordinary, so I used the discoveries as the basis for my doctoral thesis, as well as two other publications, which were ignored for several years.

It wasn’t until 1996 that anyone showed any interest in my discovery. The leading aging research at the time was being done on worms, and Tom Johnson, who was trying to identify an unknown gene that made worms live longer, invited me to present my data on the “sugar pathway” at a conference. When my presentation ended, the room was absolutely silent. The stars of the aging field, who years later would become my colleagues and friends, stared at me as if I had grown horns—no one had ever heard of the system I was working with (yeast chronological aging), nor of the genes I had identified, and anyway, very few believed that similar genes and strategies could be affecting aging in such different organisms.

A few years later, encouraged by continuing to discover similarities between my findings in yeast and those of the teams studying worms, which now included Gary Ruvkun at Harvard, I published an article proposing that many if not all organisms age in similar ways and that the genes and “molecular strategy” to achieve longer lifespans would be similar or the same in yeast, worms, mice, and, yes, humans.2 This was heresy, and the great majority of scientists dismissed it as a crazy idea with no relevance to human aging, since it was based on discoveries made in a microorganism.

2.2. Yeast, fruit flies, and dwarf mice with similar mutations in growth genes all have record longevity.

It would take another six years for our data on genes activated by sugars to get published, along with the discovery of the pro-aging genes activated by amino acids and proteins (see fig. 2.2).3 Eight more years passed before different laboratories would confirm these data experimentally in mice, and another ten years before my own lab provided initial evidence that similar genes and pathways may protect humans against age-related diseases.4

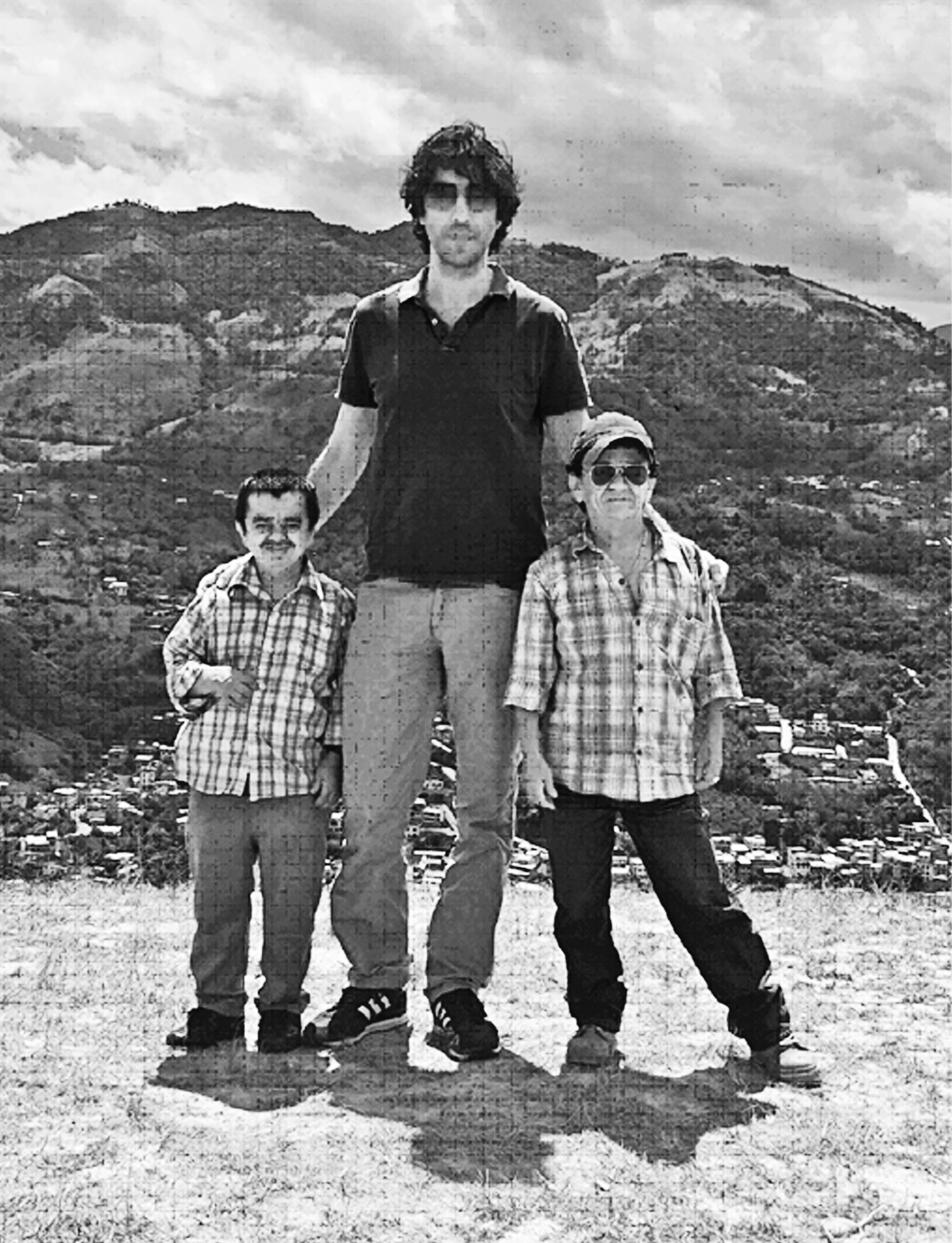

Knowing that “dwarf yeast” with longevity mutations in the growth genes (TOR-S6K) could live up to five times longer than normal yeast, and that “dwarf flies and mice” with similar genetic mutations could live up to twice as long as normal mice, in 2006 I started research on the human version of the growth gene known to correlate to record longevity in mice (see fig. 2.2). Through my colleague Pinchas Cohen, who is now dean of the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, I learned of the work of Jaime Guevara-Aguirre, an endocrinologist who had spent decades studying a community of extremely short people in Ecuador who lacked the receptor for growth hormone, a disorder known as Laron syndrome. After five years of working together, we published our findings concluding that there was a major decrease in the incidence of cancer and diabetes in subjects with Laron syndrome (see fig. 2.4), despite poor diet (consuming large quantities of fried food) and unhealthy lifestyle choices (smoking, drinking, etc.).5 Our finding made this group of short individuals from remote villages in Ecuador famous around the world—everyone wanted to hear about this group of little people who appeared to hold the secret that could protect everyone from cancer, diabetes, and possibly other diseases. We were even invited to present our research to the Pope, accompanied by one of our Laron subjects. Journalists described these people as being free from disease. “It doesn’t matter what we eat,” the Laron subjects told reporters, “because we are immune from diseases.” Of course, this is not the case; a few have developed both cancer and diabetes, but these diseases occur rarely, and much less frequently than they appear in their non-Laron relatives living in the same houses and consuming the same food. Recently, we also published our studies on the brain function of this Laron group and concluded that they have cognitive function that is typical of younger individuals.6 In other words, their brains appear to be younger than they are, which is in agreement with the findings published by the Andrzej Bartke laboratory in mice with similar mutations.7 After these studies and many trips to Ecuador, the country, particularly the isolated Andes to the south, became a magical place for me, and I go back as often as possible. Jaime and I argue all the time, but we continue to work very closely and have forged a fruitful friendship.

2.3. Me with Freddi Salazar Aguilar and Luis Sanchez Romero (both with Laron mutations) in their native Ecuador

2.4. Individuals with mutations in the growth hormone receptor are protected from disease.

These findings were the last missing pieces to support my theory that similar genes and longevity programs can protect organisms, ranging from simple ones such as yeast to complex ones like humans, against aging and disease. These alternative programs, such as those found in the Laron people, have probably evolved to deal with periods of starvation by minimizing growth and aging, while also stimulating regeneration. The mutation in the growth hormone receptor gene that these Ecuadorians carry appears to force the body to enter and stay in an “alternative longevity program” characterized by high protection, regeneration, and low incidence of disease. The rest of the book takes advantage of this genetic knowledge to identify everyday diets and a periodic fasting-mimicking diet that can regulate genes that protect against aging and diseases.

Connecting Nutrients, Genes, Aging, and Diseases

A risk factor is something that affects the probability of dying from or developing a particular disease. For example, obesity is a well-established risk factor for diabetes: it can increase by fivefold the chance of developing the disease. We think of poor nutrition, lack of exercise, and the genes we inherit from our parents as the major risk factors for diseases. But, by monitoring the age at which people are diagnosed with different diseases, we know that aging itself is the main risk factor for cancer, cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s, and many other diseases. According to recent data, the probability that a twenty-year-old woman will develop breast cancer within the next ten years of her life is roughly 1 in 2,000. The risk is 1 in 24 for a seventy-year-old woman—that’s an increase by almost a factor of 100.

As I have stated, my approach is different from that of almost all other nutrition books, in that my program doesn’t focus on achieving a healthy weight or on any one specific disease independently of the long-term consequences of a treatment. If aging is the central risk factor for all major diseases, it’s much smarter to intervene on aging itself than to try to prevent and treat diseases one by one. Even great success against one disease may be minimal or rendered irrelevant if accompanied by an increased incidence of another—few people know, for example, that curing cancer or cardiac disease today would increase the average lifespan by only a little over three years.

The lifespan of a mouse is about two and a half years, and tumors begin to appear in mice at the age of one and a half. People live on average more than eighty years, and most tumors begin to appear after age fifty. In relative terms, that is a similar proportion of life. Therefore, we can reduce the risk of cancer and many other diseases by acting on the longevity program, and we now know that we can do this through diet.

Figure 2.5 shows how sugars and proteins (amino acids) affect key genes and pathways widely recognized to accelerate aging: TOR-S6K, PKA, RAS, and IGF-1. To maximize and reprogram longevity in the human body, we need to continue to study how different diets control these genes and then apply the longevity program to all the diseases associated with aging. (See chapters 7 to 11 for disease-specific applications.) Clearly our strategy of studying the genetics and molecular biology of longevity in simple organisms paid off, though it took many years of hard work by groups made up of mostly geneticists and molecular biologists at universities all over the world.

2.5. The regulation of aging and diseases by sugar- and protein-activated pathways

From Studying Aging to Solving Medical Problems

After studying aging, my second passion, developed while working with Walford’s group at UCLA, is using the biochemistry of longevity to solve medical problems. To optimize disease prevention and treatment, we need to know what causes disease at the molecular and cellular level and to understand how we can return those molecules and cells to their youthful, fully functioning states. To attempt to treat a disease without this information is like trying to fix a car without knowing how its engine or electrical system works. Repairing cars and planes is, of course, much simpler than repairing a sick human body.

Although this is a generalization, much of medical research is based on identifying drugs that can target a specific problem associated with a disease. For example, to treat cancer, researchers developed chemotherapy and other more specific drugs that preferentially kill cancer cells; to treat multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune diseases, scientists identified proteins and drugs that reduce the activity of specific immune cell populations or the inflammatory factors they generate. I argue that this is an incomplete approach that is not “in tune with evolution” and that would greatly benefit from being combined with, and in some cases replaced by, a “longevity-based” approach, preferably one awakening a program already present in the human body, once this is further demonstrated to be effective. For example, by starving a mouse receiving chemotherapy or other targeted therapies, we protect normal cells and organs while making the therapy more toxic to cancer cells (see chapter 7); and by applying cycles of a fasting-mimicking diet to a mouse with an autoimmune disease, we reduce the number of autoimmune cells while also activating regeneration of the damaged tissues (see chapter 11). Preliminary results indicate that these strategies may also be effective in humans.

While I was a research scientist working at USC, I had the opportunity to meet with children being treated for cancer at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Italian researcher Lizzia Raffaghello, at the time a visiting scholar in Los Angeles, was puzzled by our effort to find ways to help people live longer and healthier lives to age one hundred and beyond, when her ward was full of children who might not make it to ten.

One of these patients was a girl from southern Italy. We considered isolating her neuroblastoma cells in the laboratory, to study them and understand what therapy might work best. But we came up against the hard reality that this type of study was not allowed by the hospital or by my department. The girl eventually returned to Italy, and sadly she died. I will never forget how she kept close watch on the intravenous saline solution bag, with the seriousness and maturity of a nurse ensuring a procedure is being carried out correctly.

Because of the impact that girl and the other sick children I’d met had on my vision of research, I decided to divide my lab between two areas of interest and two different missions. One team of researchers would continue to work on the biochemistry and genetics of aging; the other would work to solve medical problems using strategies based on our understanding of cellular protection, repair, and regeneration with an eye toward solutions that were inexpensive and could rapidly be translated into improved therapies. Because diet-based therapies do not involve new drugs, they can move through the Food and Drug Administration approval process quickly, and in some cases can be combined with standard-of-care drug-based therapies without FDA approval. From this effort came our discoveries of differential stress resistance and sensitization, which use prolonged fasting to push normal cells into a highly protected state while making cancer cells highly vulnerable to chemotherapy and other cancer therapies (see chapter 7). Other dietary strategies applicable to diabetes as well as autoimmune, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative disorders also came from our effort to identify simple but powerful therapies for complex problems. But before we get to the diet itself, I’ll explain how I’ve harnessed thirty years of research, both mine and that of other labs, to identify daily diets as well as periodic fasting-mimicking diets with the potential to extend healthy human longevity.