Frank Vriesekoop

CONTENTS

24.3 Integrity Issues Associated With Raw Materials

24.4.3 Agents to Enhance the Colloidal Stability of Beer

24.5 Perceived Biological Food Safety

24.5.1 Hurdle Technology and Pathogenic Bacteria

24.1 INTRODUCTION

The process of beer brewing, and beer itself, is often held in a position of repute and tradition. Beer represents centuries-old craftsmanship, produced with ingredients that have been a staple for all layers of society dating back to Neolithic times and the Mesopotamians around 6,000 to 7,000 years ago,1, 2 inspiring poetry,3 being incorporated into classical and modern art,4–10 and supporting a robust and healthy lifestyle.11 Notwithstanding the obvious presence of alcohol, which brings about the often-experienced feelings of euphoria when it is consumed in moderation,12 for a long time, beer has been consumed in preference over town water13 due to its inherent safety, which is linked to the numerous antimicrobial hurdles associated with beer.14–17 As such, beer has gained a reputation as a staple beverage with a solid and trustworthy authenticity. This authenticity is well earned and is often the basis of the integrity we award to beer.

The beer consumer relies on this integrity and places trust in the product. This trust is often based on consistency, wholesomeness, and consumer identification with long-standing values. Apart from a strong trust that beer will contain all of the perceived goodness and values, the consumer also demands a product that fulfills his/her expectations. These expectations can be in the form of a certain crystal clearness of the liquid, a particular color and/or strength of the foam, a characteristic color or hue of the liquid, an aroma that lingers but does not overwhelm, a taste that is matched by mouthfeel, and a particular sensory enjoyment that is particular to one brand and not to another. At the same time, the consumer expects a product that will not cause ill health when consumed in moderation. In fact, some consumers expect health benefits from the consumption of beer!11

This status of integrity can be underpinned by legislation such as Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), Protected Geographical Indication (PGI), or the German beer purity law—the Reinheitsgebot. Also, it demands a product that will obey international, national, or local legislative rules and regulations with regard to the ingredients used as additives or processing aids and their identification on product labels.

The brewer works hard to produce beer that lives up to these expectations. However, at the same time, brewers have to deal with commercial realities such as competition from other brewers reducing profit margins, with long and tedious supply lines to the consumer, maintenance of product quality/integrity once the beer leaves the control of the brewer, and the ability to track and trace products when there are quality or safety concerns. Furthermore, a beer that has a strong reputation for its unique characteristics might be challenged in its ability to maintain that particular product’s integrity. For instance, a beer produced in, and associated with, a specific geographical location (e.g., Ireland, the Netherlands, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, or Japan) might create a demand that overburdens its production ability. Even if the brewer could produce sufficient volumes to satisfy demand, the supply lines might be too long and tedious to guarantee maintenance of the quality characteristics associated with the brand. Additional brewing locations across a much wider geographical area could be employed in order to satisfy the demand, or the product could be produced under license or contract (often the case these days) through a coopetition arrangement. However, producing the same product at different locations could pose concerns that challenge the ability to maintain product integrity due to variations in the raw material supply, brewery configuration, cultural disparities, and legislative limitations.

This chapter will attempt to highlight the potential integrity challenges in the beer production process. It examines allergens, issues with raw materials, processing aids and additives, food safety, and certification systems.

24.2 BEER AND ALLERGENS

There are a multitude of estimates that predict the prevalence of food-related allergies within the world’s population. The estimates of the prevalence of food-related allergies range from 2% to close to 5% of the general population,18–20 with self-diagnosed allergies being even more prevalent. Allergies can be defined as having an abnormal reaction when exposed to one or more compounds in a person’s environment. This abnormal reaction is typically the result of an immune system-related response that yields symptoms that can result in mild discomfort and even in life-threatening situations! The most common routes that involve exposure to allergens are through the airways, the gastrointestinal tract, and the skin. This can lead to broncho-constriction, abdominal pains, and skin rashes. Almost all food-related allergenic reactions yield abdominal-related symptoms, which are sometimes accompanied by skin rashes and hives. People working in the brewing and allied industries, with sensitivities to various beer-associated food allergies, may suffer from a much wider range of symptoms because their route of exposure to potential allergens is much more diverse, including direct exposure to their nasal cavity, eyes, and skin.

The most complete listing of food allergens that require attention with regard to labeling of foods and beverages is the one enforced by the European Union (EU), which lists 14 allergens (Table 24.1). Among those 14, there are 3 that are commonly found in many mainstream beers and another 2 that can be found in specialty products.

Table 24.1 Common Human Allergens

|

|

Common Description |

Association With Beer |

|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Celery |

Includes celery stalks, leaves, seeds, and the root (celeriac) |

None |

2 |

Gluten |

Cereals containing gluten, such as wheat, rye, barley, and oats |

All common beer-associated cereals contain gluten. Most gluten-free beers are produced from sorghum, millet, and buckwheat |

3 |

Crustaceans |

Includes crabs, lobster, shrimp, prawns, and scampi |

None |

4 |

Eggs |

Typically refers to hen eggs, but does not exclude the eggs from others birds |

None |

5 |

Fish |

Typically, a limbless cold-blooded vertebrate animal with gills and fins, living wholly in water |

Isinglass is the collagen-rich product, used in the brewing industry as a processing aid to facilitate the removal of proteins and yeast cells |

6 |

Lupin |

Flowering and pea-bearing plant within the legume family |

No records can be found of the use of lupins in modern brewing. However, lupin has been recorded as being used as a bittering agent in ancient times |

7 |

Milk |

Secretion from mammary glands intended to be the nutritional input of mammalian neonates |

Milk as a beer ingredient is uncommon; however, the inclusion of lactose in milk-stouts is commonplace. Milk allergies are not to be confused with lactose intolerance |

8 |

Molluscs |

Typically includes mussels, oysters, squid, and snails |

Oysters are occasionally included as an ingredient in oyster stouts. However, not all “oyster stouts” contain oysters |

9 |

Mustard |

Member of the brassica family. No know cross-reactivity from other brassica |

None |

10 |

Nuts |

Fruit composed of a hard shell and an indehiscent seed |

None |

11 |

Peanuts |

Also known as a groundnut. The peanut is not a nut, instead it is a legume |

None |

12 |

Sesame seeds |

Sesame is a flowering plant whose seeds yields very large amounts of oil |

None |

13 |

Soya |

A high oil and protein yielding legume |

None |

14 |

Sulfur dioxide |

Chemical preservative and antioxidant, also referred to as sulfite |

Natural occurring at very low levels in beers. Sometimes added as an antioxidant to slow down the aging process of beer by complexing carbonyls and adsorbing oxygen |

24.2.1 Gluten

The most common and most difficult to avoid allergen that is associated with beer is gluten, which is contained within all common beer-associated cereals. Adverse reactions to gluten can be a general intolerance to gluten or more specifically—celiac disease.21, 22 The symptoms and their descriptions vary widely and include abdominal bloating, chronic diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and vomiting.21–23 In general, gluten-related disorders can be summarized as “a chronic small intestinal immune-mediated enteropathy precipitated by exposure to dietary gluten in genetically predisposed individuals.”23 Gluten represents a significant fraction of the storage proteins in grains. Although gluten is the term most commonly associated with wheat, proteins with similar allergenic reactivity have different nomenclatures in other grains.24 Wheat is by far the most gluten-abundant grain. However, sufficient gluten-like proteins (hordeins) are present in barley to cause concern.25, 26 The general popularity of beer has created a niche for specialty beers that can be drunk by those consumers who have a gluten allergy or intolerance. The most common approach to overcome these problems has been to produce beers solely from cereals that do not contain gluten, such as rice, sorghum, millet, or buckwheat.27 However, a more technical approach has been used as well, by the utilization of a de-glutinized barley malt.28, 29 De-glutinization employs the use of a propyl endopeptidase that is highly active toward celiac-active substances.29, 30 The effectiveness of this enzymatic approach is probably underpinned by the fact that the typical brewing process (mainly during mashing) already causes a 99% reduction in gluten levels in all-malt beer formulations.25, 26

The most common gluten-related disorders, including allergenic reactions, are associated with bread made from wheat. Occupation-related gluten allergies are reported among bakers,31 but none have been reported for people working in the malting or brewing industry. It is likely that people in the brewing industry with gluten-related allergies are also very interested and instrumental in the production of gluten-free beers.21

24.2.2 Fish

The inclusion of any material originating from fish has to be labeled as an allergen.

Isinglass (produced from fish bladders) can be added to freshly fermented beer toward the end of the fermentation in order to aid in the removal of yeast,32–34 or in the case of cask ales, to facilitate the elimination of yeast and proteins by precipitation from the potable portion of the cask beer.35 In wine production, isinglass is used to enhance colloidal stability36 and color stability.37

There have been no substantiated reports of allergic reactions linked to isinglass in alcoholic beverages. Nonetheless, in 2003, the EU adopted Directive 2003/89/EC1 with regard to compulsory labeling of a number of ingredients present in foodstuffs that are known to induce allergic reactions or intolerances in sensitive individuals. This list includes fish and fish-derived products. The directive states that whenever the listed ingredients/substances or their derivatives are used in the production of foodstuffs, they must be labeled without exception. Directive 2003/89/EC1 was successfully challenged by the Brewers of Europe and the Brewing, Food and Beverage Industry Suppliers Association (BFBi), citing various specific clinical trials on fish collagen that showed that none of the fish-challenged allergic individuals had a positive reaction.38, 39 Upon investigation by an EU investigative panel, it was determined that it was not likely that isinglass, when used as clarifying agent in beer, would induce a severe allergic reaction in susceptible individuals under the conditions of production and its use specified in the challenge. As a consequence of this opinion, the EU established, with the Commission Directive 2007/68/EC, a permanent exception for the labeling of fish gelatin, or of isinglass, when used as a fining agent in beer and wine.40

24.2.3 Sulfur Dioxide

Sulfur dioxide (SO2) is specifically listed in the 2003/89/EC1 directive41 and is required to be identified as present when it is used as an ingredient at concentrations of more than 10 mg/L. The same regulation regarding labeling exists in most countries. In some countries, specific regulations regarding allowable upper limits exist (Table 24.2). With varying regulations among countries, a close scrutiny of an individual country’s protocols is warranted when contemplating export.

Table 24.2 Country-Specific Regulations Regarding SO2 in Beer

Country |

Lower Limit Requiring Mention on Label (ppm) |

Maximum Legal Limit (ppm) |

|---|---|---|

Canada |

10 |

15 |

European Union |

10 |

20 |

|

|

50 with secondary fermentation in barrel/cask |

Russia |

10 |

20 |

|

|

50 with secondary fermentation in barrel/cask |

USA |

10 |

25 |

Australia |

10 |

25 |

New Zealand |

10 |

25 |

Singapore |

10 |

25 |

India |

NF |

50 |

Brazil |

NF |

50 |

Note: NF, information not found.

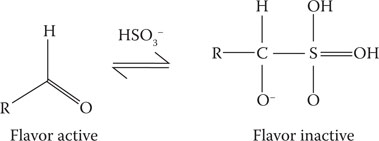

In beer, SO2 is commonly added to act as an antioxidant to scavenge oxidative compounds to delay the formation of carbonyl compounds (Figure 24.1), which could potentially lead to the formation of stale flavors42 (details in Chapter 10). The levels of SO2 added to beer are too low to impart an antimicrobial impact on the product, while other alcoholic beverages, such as cider and wines, often contain SO2 for antimicrobial purposes. These products require much higher additions compared to the use of SO2 as an antioxidative agent. The principal reason why SO2 has at best a limited antimicrobial role in beers is that at the pH of typical beers, the SO2 is predominantly present in the bisulfite form (Figure 24.2).43 The undissociated form (SO2⋅H2O) is by far the most-effective bacteriostatic form, while the bisulfite form (HSO3−) has only a limited bacteriostatic effect—and only when unbound.44,45 At the pH of beer, the bisulfite ions are mostly bound to carbonyl compounds.

Figure 24.1 SO2 reaction with carbonyls.

Figure 24.2 Effect of pH on the equilibria of SO2 species in aqueous solutions. (Courtesy of Van Leeuwen, T., A Comparison of the Chemical Analysis of Beers and Judges’ Scores from the 2004 Australian International Beer Awards, Honours thesis, University of Ballarat, 2006.)

24.2.4 Molluscs

There is ample anecdotal information available that describes the application of oysters in stouts. It appears that great variations occur in the application of oysters in the production of stouts. This varies from the addition of oyster shells to the mash tun, the addition of oyster flesh or extract to the kettle, the addition of oyster flesh or extract to the fermenter, the addition of oysters to the finished beer, or no addition of oysters at all. The application of oysters to the beer production process is said to improve head retention and the flavor of the stout.46 The addition of oyster shells at the end of the mash is said to extract calcium carbonate from the shells, which helps reduce the tannic astringency that can result from the roasted grains used in stouts (J. Downing, personal communication), which will yield a water makeup similar to the hard water used in typical stout brewing areas. To date, there have been no reported cases of mollusc-related allergic reactions following the consumption of oyster stout.

24.2.5 Milk

Again, much is written about so-called milk stouts and much of the information is anecdotal. An early patent was granted for the production of a milk beer containing malt, whey, and hops,47 but no direct information can be found regarding the application of intact milk in the production of either milk beer or milk stout. A number of attempts have been made to produce beers or beer-like beverages with whey.48 In some, the whey sugars were targeted as the sources of ethanol by employing a lactose fermenting yeast,49 while in others, the presence of lactose caused product spoilage.50 Over the years, the addition of whey during beer production must have yielded stouts where the typical astringency was masked by the sweetness of the nonfermentable lactose contained in the whey.51 The designation “milk stout” became prohibited in the United Kingdom in 1946 after it became clear that lactose was the added ingredient to the beers labeled as “milk stout.”52 The use of lactose in the production of “milk stouts” or “sweet stouts” is still commonplace today.51 To date, there have been no reported cases of milk-related allergic reactions following the consumption of milk stout.

When producing beers with potentially allergenic ingredients, the process may require compulsory labeling on equipment that is used for the production of the beers that do not contain these ingredients. Indeed, appropriate cleaning and validation procedures must be in place. The use of shared equipment can result in cross-contamination of allergenic ingredients if proper care is not taken. The vast majority of people with known food allergies can tolerate exposure to trace amounts without any adverse health effects. However, Rona and coworkers53 have argued that a small but significant proportion of people suffering from allergies are affected following exposure to even trace amounts of allergens.

24.3 INTEGRITY ISSUES ASSOCIATED WITH RAW MATERIALS

The raw materials used in the brewing process make up the four principal ingredients upon which beer is founded: water, cereals (malted or unmalted), hops, and yeast. The raw materials provide the intrinsic characteristics that underpin beer’s integrity.

24.3.1 Water

Water, as the largest volumetric contributor to beer, is very much influenced by its source. Many brewers will use water that is readily available at or near the site of the brewery. In times long gone, brewers would produce beers that suited the readily available raw materials, which ultimately yielded geographically specific beer styles. Examples of these beers are some British ales and Dortmund lagers that require hard water; London porters and Dublin stouts are better suited to be produced with intermediate hardness in the water. Pilsners are better produced with very soft waters. In modern brewing operations, multiple beer styles are produced at single sites with a single water source. Methods, such as reverse osmosis, allow brewers to strip most minerals from the water and then later reintroduce mineral salts into the process that is best suited for individual beer styles.54 When using salts to adjust the mineral content of the brewing water, it is imperative that food-grade salts are employed to maintain suitable traceability for quality and integrity assurances (further details in Chapter 4).

24.3.2 Malt

The main process preceding the actual brewing process is malt production. The principle aim of the malting process is to induce the in situ biosynthesis of endogenous enzymes for the hydrolysis of storage carbohydrates and proteins, without causing a significant hydrolysis of storage nutrients. The latter process is reserved for the mashing step during actual brewing. The overall malting process is person-made management of a natural process—namely the induction of a seed germination process that could ultimately yield a plant. As described in Chapter 5, gibberellic acids are plant hormones that induce the breaking of dormancy, enzyme induction, and germination. The addition of exogenous gibberellic acid during the steeping step will accelerate the onset and progress of germination.55 When used, exogenous gibberellic acid can reduce malting time by more than 24 hours (further details in Chapter 5).

Apart from the use of exogenous gibberellic acid to improve the economy of the malting process, maltsters have endeavored to minimize malting losses. One such loss involves minimizing the amount of culms (the rootlets produced by the germinating grains) that are not part of the malt used during brewing but that remain following the completion of kilning. Rootlet growth can be inhibited by the addition of bromate56–58 to either the steep or cast into the germination box. The application of bromate delays the development of proteolytic activity during germination and subsequently restricts respiration and rootlet formation.56 Rootlet growth is less vigorous compared to untreated barley, and less heat is generated during the germination stage. Malting losses can be reduced by 1% to 2% by the application of bromate,56 and there is typically a slight increase in the hot water extract following the addition of bromate; however, a lower free amino nitrogen (FAN) yield usually occurs.58 Regardless of the direct economic benefits associated with the application of bromate during malting, its application is rarely used currently. Bromate has been found to be mutagenic,59, 60 and its association to food and beverages includes drinking water, bread, and malt. Bromate exposure causes oxidative damage to the guanine bases of DNA, which can result in chromosomal mismatches and damage. Furthermore, it has been found to be cytotoxic and to cause changes in renal gene expression.61 The negative health issues associated with bromate warrant the selection of malts whose production has not involved the addition of bromate. However, as an alternative, rootlet growth can also be inhibited by the addition of a small proportion of ethanol to the steep water without reducing the hot water extractability of the resultant malt.58 However, it should be emphasized that additives to control rootlet growth are not currently employed.

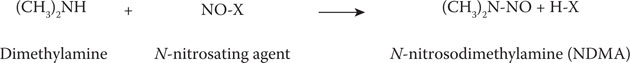

When cereal germination is complete, in order to arrest the germination process, the cereal grains are dried to preserve the enzymatic activity that is later relied upon during mashing. Drying occurs in a kiln, where hot air is driven through a bed of wet germinated grain. The generation of hot air was traditionally achieved by direct heating, where the flue gases were drawn into the kiln. The traditional fuel used to generate heat for the kilns was typically linked to readily available fuels. The passage of the flue gases through the drying malt bed often imparts a fiery or smoky flavor to the malt, the like of which we nowadays describe as specialty malts, such as rauch and peated malt. However, most (but not all) consumers and brewers prefer a beer free of this smoky character, which initially involved the use of coking coal, anthracite, oil, or natural gas as the fuel in direct-fired kilns.62 Direct firing of kilns poses two main problems with links to the integrity of the beers made from these malts. First, some fuels—such as coal and anthracite—can contain arsenic that can become volatile and be introduced to the drying malt.63–65 Arsenic readily volatilizes to such an extent that greater levels of arsenic have been found in the dust from malt kilns than in the ashes left in the furnace.66 Arsenic’s volatility has been blamed for the elevated arsenic content in malt and also, in some instances, hops when dried in coal burning kilns.64 Arsenic causes acute and chronic adverse health effects, including neuritis resulting in paresthesia, numbness and pain in the extremities,67 and cancer.68 Although many fossil fuels contain traces of arsenic, the volatilization can be avoided by achieving sufficiently high temperatures in the kiln because arsenious oxide reacts with bases in the coal and forms nonvolatile compounds.69 This also resulted in the use of lime filters, through which the kiln gases are passed before reaching the drying malt. The lime binds the volatile arsenic and renders it nonvolatile,63, 69 thus effectively removing the arsenic from the drying air. A second issue related to direct firing of kilns is the fact that this can lead to the formation of N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA).70–77 NDMA is a member of a family of extremely potent carcinogens, the N-nitrosamines, which are known to cause cancers of the esophagus, stomach, and nasopharynx.78 Nitrosamines such as NDMA are formed when amides react with oxides of nitrogen (NOx) (Figure 24.3).79 At the temperatures employed in the kiln, atmospheric nitrogen (N2) readily oxidizes to form (NOx).

Figure 24.3 Chemical reaction leading to the formation of N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA).

During the germination step, alkaloids such as hordenine and gramine are formed in the malt roots, which react with NOx to form N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA),77 of which a noteworthy portion makes it into the beer.70–72, 74, 76, 80 The current international threshold for NDMA in beer is set at 0.5 ppb.72, 80 In one of the earliest reports on NDMA in beer, 70% of the beers on the market in the late 1970s contained NDMA at levels in excess of 0.5 ppb.73 Since that time, much of the kilning technology used in the malting industry has been modified from direct-fired kilns to indirect-fired kilns, which has resulted in a drastic decrease in the levels of NDMA found in commercially available beers to approximately 1% of beer with NDMA in excess of 0.5 ppb.76 Not all of the reduction in NDMA in beers is due to the employment of indirect fired kilns; alternative (but less effective) methods can be applied to direct-fired kilning that reduces the levels of NDMA. The practice of “sulfuring” causes a significant reduction in the formation of NDMA during direct-fired kilning.70, 79, 81, 82 Sulfuring typically involves the introduction of SO2, at the combustion stage of the kilning process, in the form of burning sulfur.81 The presence of SO2 in the flue gas competes with O2 in the reaction with N2 and thus decreases NOx formation causing a reduction in the NDMA that is formed.81 This sulfuring can also be achieved by using a sulfur-rich fuel82 or by spraying sulfuric acid on the germinated grain prior to kilning.79 Despite best efforts to avoid direct contact of the combustion air with the drying malt, there are specialty malts that cannot be produced without drying by direct exposure to combustion gases. These specifically include smoked malts for the production of peat-driven beers or rauchbiers. Not surprisingly, rauchbiers are the beers with the highest reported levels of NDMA.73 The use of sulfuring to reduce malt NDMA can have negative environmental effects.

24.3.3 Hops

Most beers are flavored with hops83 (details in Chapter 7); however, varieties of fruits and spices have also been and are still used in the brewing process.84–87 The hop flavoring components are obtained from the female flowers of the hop plant and dried immediately following harvesting. The dried hops are extremely voluminous and can be either compressed into pellets for ease of handling as a raw ingredient, or the principal active components (the hop oils and resins) can be extracted into a concentrate. The use of hop extracts permits brewers to fine-tune the bitterness levels of their beers at the completion of the production process, which allows for cost savings and flexibility in production. The early attempts to create hop extracts included the use of organic solvents such as petroleum ether, hexane, and trichloroethylene,88 which all have been deemed to be (potentially) toxic and could leave trace amounts in the final beer. Advances in extraction technology and nontoxic solvents have seen the use of ethanol and supercritical carbon dioxide in the production of hop extracts that do not have toxic potential.

24.3.4 Yeast and Fermentation

The fermentative organisms involved in the production of beer are predominantly either Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Saccharomyces pastorianus yeasts. Although a bacterial presence occasionally is welcomed for particular styles, none of the typical fermentative organisms (yeast and bacteria included) are known to cause adverse effects beyond spoilage.17, 89, 90 The principle metabolic product of yeast is the causative agent of beer-induced euphoria and inebriation; however, there are no beer-associated yeast fermentation products that cause underlying health issues.

In other alcoholic beverages—for example, whiskey and some fortified wines such as sherry, port, and Madeira—ethyl carbamate has been identified as an important product of yeast metabolism, but not in beer. Ethyl carbamate is a genotoxic and carcinogenic compound that is commonly found in high-alcohol-containing beverages and some other fermented foods.91, 92 In the previous editions of this handbook, a link to ethyl carbamate formation in beer has been dismissed. Studies have also been conducted to determine whether yeast foods contribute to the formation of ethyl carbamate (urethane) in beer or wine. It has been suggested that ethyl carbamate occurs naturally because of a reaction of carbamyl phosphate with ethanol. Fermentation experiments, showed that ethyl carbamate was not formed during fermentation, either in the presence of “yeast foods” or when the fermentations were directly supplemented with urea. In beers, ethyl carbamate has only been found in trace amounts.91, 92

24.4 MIRROR, MIRROR ON THE WALL; WHO IS THE FAIREST BEER OF THEM ALL? (PROCESSING AIDS AND ADDITIVES)

The visual appearance of beer is the first parameter that most consumers encounter and is very likely to influence the consumer’s perception of that beer.93 The brewer has a wide range of contrivances in his/her beer-beautifying “tool kit” that empower him/her to adjust or fine-tune the outward appearance of the beer. The most visual characteristics of any beer are the foam and its stability when poured,93, 94 its color,95, 96 and its crystal clear appearance.97, 98 It should be noted that these parameters are not pursued by many beer drinkers because of their unfortunate habit to drink directly out of the bottle or can!

24.4.1 Foam Stability

Regardless of whether it is customary for the foam in a glass of beer to be “two fingers” in depth or only just marginally present, the stability of the head of foam is one of the first visual beer quality characteristics encountered by the consumer.99 In order to enhance the natural foaming abilities of beer, there are various additives that have been employed over the years. Propylene glycol alginates are most commonly used in the brewing industry to enhance beer foam stability.99, 100 Their use protects beer foam against contaminants—for example, dirty glasses and lipstick—at dispense and consumption, counteracts some of the components of beers that can act as foam inhibitors, improves foam cling to the side of glass, and enhances head retention of poured beers. Propylene glycol alginates have not been shown to impart any adverse reaction in healthy individuals101 and only mild allergic reactions in sensitive individuals.102

Before the common employment of propylene glycol alginate, various brewers used a range of different additives to enhance foam stability. In the early 1960s, some brewers began adding cobalt to beer in order to protect foam stability.80, 103 The addition of trace amounts of some metals such as cobalt, nickel, and iron improved head retention in the presence of iso-α acids.104–106 The amount of cobalt in the beers ranged from 0 to 5 ppm. This might have been an acceptable level of cobalt intake when beer was consumed in moderation. However, the consumption of cobalt-containing beers by heavy beer drinkers (10+ servings/day) resulted in a large number of cardiomyopathy cases (166 cases) with a nearly 40% mortality rate.80, 107 Although cobalt is an important trace element in human nutrition,108 excessive cobalt intake in combination with heavy drinking and poor nutrition appears to have caused an abnormally heightened sensitivity to cobalt exposure. Cobalt addition to beer was not uncommon in the 1960s and was more widespread than just the beers associated with the cobalt-induced cardiomyopathy cases. However, not all beers that contained cobalt as a foam-enhancing additive resulted in reported health problems.80, 107, 109, 110

Another past attempt to enhance foam stability was the notion to add fluorocarbon gas in addition to carbon dioxide (CO2).111 Fluorocarbons such as Freon increase the stability of the individual CO2 bubbles by toughening the bubble’s liquid skin, providing a thicker and denser foam, thus enhancing overall beer foam stability. Although fluorocarbon gas was initially hailed as an inert gas with regard to humans (apart from asphyxiation) and was widely used as a refrigerant, it was quickly realized that it was a causative agent in the depletion of ozone and thus its use posed a significant negative environmental issue.112

A natural means of enhancing foam stability is through the use of hops (details in Chapters 7 and 20) with high levels of isomerized hydrophobic alpha acid.83, 99, 113 The isomerized alpha acids are the major source of bitter flavor in beer.83, 114 The hydrophobic isomerized alpha acids appear to partition into the foam of the beer where they interact with the proteins and stabilize the foam bubbles and enhance cling.113, 115 The brewing industry has seen the introduction of reduced isomerized alpha acids, which are often used to minimize lightstruck (skunky) character in beer. Lightstruck character ultimately expresses itself as the formation of 3-methyl-2-butene-1-thiol due to the riboflavin-induced photodecomposition of isohumulone.37 The chemical reduction of components of hops such as isohumulone makes these compounds even more hydrophobic, which then makes the isohumulone less susceptible to light degradation, and further enhances foam stability and cling.115

24.4.2 Beer Color

Although raw materials used in the production of beers have a profound influence on beer color, the color range is from pale yellow to dark brown, with occasional hues of red. The compounds that underpin these colors are quite different, and they impart a distinct visual association with the beer and its style. The color obtained by the beer is directly acquired from its raw materials, which includes various forms of malt ranging from extremely pale pilsner malts to crystal malt and roasted malts and grains,116, 117 but the color of beer can also be influenced by added fruits.85 Most brewers will produce their beer to tightly defined specifications, which includes the following: alcohol content, bitterness, long-term colloidal stability, and color. However, despite greater process control, the natural ingredients used in the production of beer introduce a level of variance on some quality attributes that can hinder precision brewing, and often the tight quality specifications are not entirely met. As a consequence of these biological variations, some brewers make postfermentation adjustments to beers in terms of bitterness, long-term colloidal stability, and color. The most common color adjustment that used to occur was the use of exogenous caramel in order to achieve a preset color intensity. The addition of caramel to beer has been permissible for some time118; this allows fine-tuning of color because it is easier to add color to beer rather than to remove it. Caramel is listed under its e-number of E150. However, there are four sub-categories of E150, namely: E150a (plain caramel), E150b (caustic sulfite caramel), E150c (ammonia caramel), and E150d (sulfite ammonia caramel). Caramels E150c and E150d are distinctively different from the other two caramels in that their production process involves the use of ammonia or its salts.119, 120 The inclusion of ammonia or its salts in the caramel production yields measurable levels of the neurotoxin and carcinogen, 4-methylimidazole.121–123 All four types of caramel are readily available and used in food and beverage production. All caramels contain compounds that have, in one way or another, imposed a negative influence on human health at high enough doses. All caramels contain 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde (5-HMF), which is considered to be an irritant to mucous membranes (eyes, upper respiratory tract) and the skin,124 while 2-acetyl-4(5)-tetrahydroxybutylimidazole (THI) is exclusively present in caramel E150c.124 THI has been shown to act as an immune suppressor in animal models by preventing T-cell export from the thymus.125 From a toxicological point of view, it has been shown that caramels produced in the absence of ammonia are recommended for the use in foods and beverages,121–124, 126 and caramels produced with ammonia should be avoided by the brewing and other industries.

24.4.3 Agents to Enhance the Colloidal Stability of Beer

Most beers are at their optimal quality when first brewed and packaged; the longer they remain in storage before consumption, the greater the changes as quality can be negatively affected by physical and chemical changes during storage (see details in Chapter 21). One of the quality parameters that influences the cosmetic appeal of many beers is its colloidal stability, which is typically represented by its crystal clear appearance.97, 98 The principal cause of colloidal instability in beer is the formation of protein-polyphenol complexes that, over time, aggregate into larger particles that have the ability to cause a clearly perceived haze. The commonly used solution in the brewing industry is to remove either the most haze-sensitive proteins from the beer or the polyphenols/anthocyanins from the beer postfermentation and prior to packaging.97, 127, 128 Protein-reducing processing aids and additives include silica gels, bentonite, papain, and tannic acid,129–132 while the most commonly applied additive for polyphenol removal is polyvinylpolypyrrolidone (PVPP).133, 134 None of the aforementioned documented processing aids and additives have been linked to any adverse effects to human health following consumption in beer.

Before the availability of PVPP to the brewing industry in the late 1970s and early 1980s,135 the application of formaldehyde during the mashing process to reduce haze-related polyphenols was commonly employed.136–138 Formaldehyde addition during mashing was found to markedly reduce the tannin content while only marginally reducing the wort total soluble nitrogen content.136, 137 The notion was that formaldehyde is extremely volatile and therefore would be removed during the wort boil. The findings at that time were that the residual formaldehyde content in formaldehyde-treated beers was comparable to untreated beers; therefore, formaldehyde treatment was not considered to be a health risk. Although formaldehyde is a common intermediate and the by-product of metabolism in almost all living organisms, exposure to high concentrations has been shown to react with proteins and genetic material causing mutations.139 The practice of formaldehyde addition to mashing has been abandoned by the brewing industry. However, reports of formaldehyde in finished beer occasionally occurs and the concentrations of formaldehyde found in beer are usually well below acceptable levels.140, 141 Nevertheless, the presence of any concentration of formaldehyde is frowned upon because of its reputation as an embalming material!

24.5 PERCEIVED BIOLOGICAL FOOD SAFETY

24.5.1 Hurdle Technology and Pathogenic Bacteria

The microbial safety and stability, the nutritional and sensorial quality, and the economic potential of many foods, including beers, are maintained using a combination of preservative factors (hurdles)—this is termed “hurdle technology.”14, 142 By employing numerous hurdles at reduced levels, rather than a single hurdle at an intense (single) level, a product can be produced with more desirable organoleptic properties. A historical example of the applied use of hurdle technology in beer is in the preservation of India pale ales (IPAs). During the late 1700s, ales destined for British troops in India spoiled very quickly during the long sea journey.143 British brewers recognized the need to increase the stability of their beers, and by the early 1800s, this was achieved by brewing beers with higher levels of hops and ethanol, both of which contribute antimicrobial properties.14, 17 Beer contains an array of antimicrobial hurdles that, under most circumstances, prevents the growth of pathogenic microorganisms and limits spoilage bacteria to a small number of genera. Among these hurdles that ensure the safety of beer are the following: kettle boil, the presence of hops, ethanol, and carbon dioxide, the low pH, and the lack of available nutrients and oxygen.14 Beer is more susceptible to undesirable microbial growth when one or more of these hurdles is absent or present at a reduced level. For example, it has been found that beers with a combination of any of the following factors: elevated pH levels, low ethanol, low CO2, and added sugar (primed) were more prone to spoilage144 and even permitted the growth of pathogenic bacteria.15–17 With ethanol being the greatest intrinsic antimicrobial hurdle in beer,15 it is advised that due attention is paid to the remaining antimicrobial hurdles during the production of reduced-alcohol or alcohol-free beers as these beers can support the growth of pathogens, especially at slightly elevated pH levels. Therefore, pasteurization and pH values should be closely monitored during the production of unpasteurized low-alcohol and alcohol-free beer, which would not be without risk from pathogenic bacteria.15

24.5.2 Mycotoxins

Apart from potential risks from bacterial pathogens in beer, an ever-present risk is the occurrence of mycotoxins in beer. Mycotoxins are secondary metabolites produced by fungi that have a deleterious effect on human health.145, 146 Although not all fungi produce mycotoxins, those that are known to produce mycotoxins in beer-related materials are listed in Table 24.3.

Table 24.3 Mycotoxins in Beer

Type of Toxin |

Abbreviation |

Organism |

Pathogenicity |

|---|---|---|---|

Aflatoxin |

AF |

Fusarium |

|

Ochratoxin |

OTA |

Penicillium |

|

Fumonisins |

FM |

Fusarium |

|

Deoxynivalenol |

DON |

Fusarium |

|

Nivalenol |

NIV |

Fusarium |

|

HT toxin |

HT |

Fusarium |

|

Ergot |

ERG |

Claviceps |

|

Zearalenone |

ZON |

Fusarium |

|

Most of the mycotoxin producing fungi are limited to various species belonging to the genera: Fusarium, Aspergillus, Claviceps, and Penicillium.146–149 Some mycotoxins impose a severe health risk through their ability to cause cancer, especially aflatoxins and to a lesser degree ochratoxins and fumonisins (Table 24.3), for which not enough conclusive evidence has been provided in relation to their carcinogenic ability.150 Although most of the other mycotoxins might not be carcinogenic in nature, their ability to cause other toxic effects is well documented.146, 147, 150 Mycotoxins such as deoxynivalenol, nivalenol, and the HT toxin display cytotoxic effects, resulting in the inhibition of protein synthesis together with immunosuppressive effects.150 The mycotoxin zearalenone stimulates growth of cells with estrogenic receptors, possibly causing infertility, vulval swelling, and mammary hypertrophy in women. In males, it causes feminization, including shrinking of testes and enlargement of mammary glands.150, 151

Most mycotoxins enter the beer production process via the grains152–154 used in beer production, with oats being the least likely grain to host mycotoxins.154 Both the malting and brewing processes have very little influence on the concentration of some mycotoxins,155, 156 with a substantial amount remaining in the final product. Many mycotoxins tend to be washed off the grain during the steeping process. However, their concentration has been seen to increase again during the germination step of the malting process.156 The survival of many mycotoxins during kilning and the wort boil is probably indicative of the fact that most mycotoxins are reasonably heat stable. The fermentation process tends to cause some degree of mycotoxin reduction due to the adherence of mycotoxins to the yeast cell wall.157 This property has been exploited in the feed industry by the inclusion of spent yeast in poultry feed to reduce the potential negative impact of mycotoxins in the feed.158 Although the fermentation process can reduce mycotoxin loading in beer, yeast itself is sensitive to the elevated presence of certain mycotoxins,159 causing an inhibitory effect with regard to growth.

The level of mycotoxins in malt and beer has been regularly monitored and reported.147, 149, 156, 157, 160, 161 It has to be stressed, however, that many mycotoxins are present in a conjugated (or masked) form,162, 163 which means that not all forms of the same mycotoxins are detected in a routine analysis. Mycotoxins are also toxic to plants, and many have evolved detoxification systems to counter a wide range of potentially toxic compounds. The detoxification systems found in plants follow either a hydrolytic or oxidative route, or the mycotoxins become conjugated through the addition of glycosyl, malonyl, or sulfur groups.162 Many of the hydrolyzed or oxidized forms of mycotoxins have a marked reduction in regard to plant toxicity but retain most of their toxicity against animals. The conjugated mycotoxins often become nontoxic or have a significantly reduced toxicity.162, 163 Many organisms have evolved with active mechanisms for the removal of glycosyl, malonyl, or sulfur groups.164 This means that during further biological processing of malt into beer there is the possibility that previously masked mycotoxins could revert to their original form and pose a toxic risk. No reports in regard to the potential of “unmasking” of masked mycotoxins are available but a liberal interpretation of mycotoxin data might be warranted.

24.5.3 Biogenic Amines

Biogenic amines and polyamines are compounds that are typically derived from the decarboxylation of amino acids.165 These amines are natural products related to intercellular communication in human and animal physiology, with the most relevant ones in animal physiology being histamine, dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenaline.166 However, biogenic amines are also readily found in foods,167 especially fermented foods and beverages.165, 168–171 An excessive dietary intake of biogenic amines can result in adverse reactions such as headaches, nausea, rashes, and hypertension, especially in individuals that are naturally sensitive to biogenic amines or in those whose biogenic amine detoxification ability is impaired through the use of medication.60, 172 Many beers contain biogenic amines71, 72, 165, 173–177 at greatly varying concentrations (Table 24.4).

Table 24.4 Biogenic Amines and Polyamines in Beer170,171

Compound |

Biogenic Amine |

Polyamine |

NOAEL (ppm) |

Range in Beer (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Tyramine |

Y |

|

2,000 |

ND—67.5a |

Histamine |

Y |

|

50 |

ND—21.6b |

Putrescine |

|

Y |

2,000 |

ND—30.7a,b |

Cadaverine |

|

Y |

2,000 |

ND—49.1a |

Spermidine |

|

Y |

1,000 |

ND—9.3b |

Spermine |

|

Y |

200 |

ND—15.3b |

Tryptamine |

Y |

|

NE |

ND—10.1a |

Agmatine |

Y |

|

NE |

ND—46.8a |

Phenylethylamine |

Y |

|

NE |

ND—8.3a |

Sources: aKalač, P., and Křížek, M., J. Inst. Brew., 109, 123–128, 2003; bLozanov, V., Biogenic polyamines in beer, online chapter, in Beer in Health and Disease Prevention, Preedy, V.R., Ed., Elsevier Academic Press, Amsterdam, e106–e111, 2009.

Note:NOAEL, no observed adverse effect level; ND, not detected; NE, not established.

However, the concentration of any of the biogenic amines found in beer is still very low when looking at the value of the no-observed-adverse-effect-level (NOAEL), which indicates the level of exposure (dietary intake) where no lasting negative effects are noticed in a healthy individual.178 This does not mean that in the marketplace there are no beers that will cause a biogenic amine-related response, rather it means that the risk of a significant adverse reaction to biogenic amines through the consumption of such beer is very low. Most of the biogenic amines in beer are derived from either the hops or the malt or are due to bacterial activity during or postfermentation.165 It has to be noted that polyamines play an essential role in plant physiology,179 where they fulfill a variety of roles. The malting process appears to be the largest generator of biogenic amines, with some biogenic amines being absent in the raw barley (e.g., histamine and tryptamine), but all biogenic amines can be detected in the final malt.165, 180 The formation of biogenic amines during the malting process appears to be influenced by conditions that influence bacterial activity such as time and temperature during germination, kilning temperature, and CO2 levels.180 The mashing conditions are usually prone to the generation of more biogenic amines,165 while the wort boil will essentially establish the levels of biogenic amines due to their heat stability.181 Very little or no biogenic amines are formed during typical yeast fermentations.165 This means that removal of all microbiological activity and maintaining an appropriate cold chain will limit any postfermentation increase in beer-based biogenic amines.169 Although bacteria, typically found in the malting process, are most likely to have the ability to generate biogenic amines, the application of specific starter cultures that are capable of degrading biogenic amines182, 183 could be another tool to limit the amount of biogenic amines in beers.

24.5.4 Certified Beers

It might be the intention of brewers to produce beers that can be labeled with a particular certification. Examples of certification exist in the form of organic beers, Kosher beers, Halal beers, and beers with a protected geographical indication. With the latter, it is more about the protection of an intellectual property.184 Since 1992, the EU has protected high-quality agricultural products and foodstuffs based on their geographical origin. This has been achieved using special quality schemes under the regulation (EU) No. 1151/2012. The regulation establishes three different schemes: Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), Protected Geographical Indication (PGI), and Traditional Speciality Guaranteed (TSG). Each scheme has its own characteristics and a specific label, which allows the identification of products protected under these regulations. According to (EU) No. 1151/2012, these schemes have the following characteristics: PDO identifies a product that has been produced, processed, and prepared within a specific geographical area. Its quality or characteristics are essentially or exclusively due to the geographical environment using a recognized human know-how. PGI denotes a product linked to a specific geographical area by its quality or reputation, in which at least during one stage of production, processing, or preparation takes place in that region. Although TSG highlights traditional characters, it safeguards these methods of production and recipes. The principal aim of these schemes is to differentiate products of high quality linked to their origin. This ensures product authenticity and communicates this to consumers as well protecting product names from misuse and imitation. Under the same rules, EU quality schemes can also serve as marketing tools, adding economic value and providing a regional and cultural identity to protected beers.184, 185 Currently, there are 27 beers in the EU listed under the PGI and TSG schemes; Germany and the Czech Republic have 9 PGI beers each; Belgium has 5 TSG beers; the United Kingdom has 3 PGI beers; and Finland has 1 TSG beer. The protection under the EU scheme is not indefinite. Throughout Europe, five beers have had their special protected geographical indications removed. These were always voluntary, but the main underlying reason for this voluntary removal of protected geographical indication has been because the owners of the brand no longer wished to protect the brand name for marketing reasons or because of the relocation of the brewing site for the protected beers. For instance, “Newcastle Brown Ale” (United Kingdom) and “Gögginger Bier” (Germany) were voluntarily deregistered because the actual production processes moved out of the initially designated area.186 Therefore, the quality and/or reputation of beers protected under these labels was significantly attributable to their geographic origin, which for many people is a deep-rooted sign of product integrity.

Other examples that are more driven by consumers’ convictions include nongenetically modified organisms (non-GMO) or produce, beers labeled as “all natural,” “organic,” or beer “brewed according to the German Beer Purity Laws” (the Reinheitsgebot). Each of these “certifications” go to the heart of the integrity of the beers that are labeled as such. The latter beers, brewed according to the German Reinheitsgebot (which was proclaimed in 1516), can only contain barley, hops, and water as ingredients. Yeast was not initially included as a named ingredient because the concept of yeast as an active ingredient to facilitate the fermentation was unknown until 1680 (details in Chapter 1). The emphasis was on barley as a grain for brewing, following a limitation on the use of grains that were typically used for a more important food staple—bread. This meant that local brewers could not use wheat or rye in the production of beer to ensure that the general population had access to bread as a staple part of their diet. The decree has also been used, for example, to protect locally produced beers in Bavaria, from imported beers, and elsewhere to impose trade barriers based on the raw materials used in the production of beer.

Certifications such as Kosher and Halal are driven by religious dogmas that embed trust and security in beers that carry the label. Both labels can only be attained after a specific level of scrutiny that is facilitated by a person of “standing” and follower of the doctrine within the specific religion.187, 188 With regard to Kosher beers, there are very few restrictions, and most beers that are produced by typical means do not infringe upon Jewish dietary laws. Kashrut, a set of Jewish religious dietary laws, provides guidelines on which products and which of the ingredients from which they are produced can be incorporated into Kosher foods.189, 190 Most beers are Kosher because the typical ingredients used to produce beer (malted barley, hops, yeast, and water) cause no kashrut-related concerns. However, the use of isinglass as a clarifying agent can potentially cause concern. When obtained from the swim bladder of sturgeons, a non-Kosher fish, isinglass is only permissible if it is removed from the beer by a subsequent process such as filtration.188 This leaves traditional British real ales with questionable Kosher status if the isinglass used is obtained from a non-Kosher fish such as the sturgeon. When other atypical ingredients are used in the production of beers, a closer study might be required to justify the Kosher label on such beers. For instance, the inclusion of lactose can impede the ability to maintain a Kosher certification because of its dairy origin.189 Similarly, Islamic religious dietary rules can exclude beer from consumption. Food and beverages that are allowed to be consumed are deemed to be Halal. Food and beverages that do not comply with the Islamic dietary rules are deemed to be Haram. Traditional beers are considered to be Haram because of the presence of alcohol and not because of the raw ingredients that might be used to produce the beer. However, cereal-based alcoholic beverages are explicitly mentioned in the Quran as being allowed to be consumed, as long as the person consuming the drink does not become intoxicated.191 All grape-based alcoholic beverages (Khamr) have always been considered Haram,192 but the prohibition incorporated all alcohol-based beverages in the eleventh century. Beers can be considered Halal if they can be produced and offered for consumption without the presence of alcohol.193 There are numerous methods that can be employed to produce a beer without alcohol in the final product,194 and the beer can then be considered Halal.

There are two other certification systems that are part of the modern age and go to the root of people’s lifestyles, beliefs, and convictions, and these are not religion-based. They involve organic produce and produce that is non-GMO.195, 196 The organic food and beverage market is rapidly expanding, especially in developed countries where an increasing fraction of “green consumers” take environmental factors and intrinsic quality and safety characteristics into consideration when making their purchasing decisions.197 Consumers of organic produce rely heavily on physical product labeling that employs certification logos,198 with a wide range of certification schemes available. Much of the organic movement focuses on the farming methods, processing procedures, and subsequent brewing of these raw materials into a final product that embraces the exclusion of chemicals such as herbicides and pesticides from the supply chain, while also excluding genetically modified raw materials.195–197 A wide range of organic beers are available on the market and most of them (not all) are produced by smaller craft breweries. This is predominantly driven by the fact that, despite the ready availability of organic barley, hops are still not sufficiently available in an organic form,199 but quantities are increasing. Although all organic beers will be non-GMO by extension, claims of non-GMO do not always translate into a product being organic.196 In fact, there are currently no beers on the global market that are exclusively labeled as containing genetically modified ingredients. When specific GMO-related labeling requirements are demanded, these typically only refer to the main ingredients and not necessarily to the processing aids and additives employed. Care should be taken when selecting processing aids and additives, especially nonmalt enzymes that are used during the brewing process. Many of these enzyme preparations are available to the brewer in order to enhance the quality of the beer or to assist with processing issues.200 Examples of these include the following: amylolytic enzymes in the production of low carbohydrate beers,200, 201 proteolytic enzymes that are used to enhance wort FAN and reduce potential colloidal haze issues in beer,202 and enzymes to intensify the maturation process in brewing.200, 203 Some of these enzyme preparations are produced by genetically modified microorganisms. For instance, a commonly applied endo-protease is produced by a genetically modified strain of Aspergillus niger, which contains additional copies of its own endo-protease gene.204 This same enzyme preparation is also used for the de-glutinization of malted barley so that the resulting beer can then be marketed as gluten-free.28, 29 Similarly, an alpha-acetolactate decarboxylase produced by a genetically modified strain of Bacillus subtilis, containing the gene from Bacillus brevis, is commercially available for the rapid removal of diacetyl yielding intermediates.205 Another example of a GMO-derived commercially available enzyme preparation is the de-branching amylolytic enzyme pullulanase, which is synthesized by a genetically modified Bacillus subtilis containing the gene for pullulanase from Bacillus acidopullulyticus.204

The inclusion of enzymes as brewing processing aids from genetically modified organisms yields obvious benefits with regard to processing efficiencies and beer quality parameters. When claims of “all natural,” “organic,” and “GMO-free” are entertained, a close scrutiny of suppliers providing processing aids and additives is warranted. The use of GMO systems in brewing is still considered with great reservations!

24.6 CONCLUDING REMARKS

For many generations to come, beer will remain an inspiration for lovers of life, art, and health. In its vibrancy, the brewing and allied industries will always be innovative, will embrace cutting-edge technologies to improve production economies, and will be ahead of new consumer trends. This will inevitably move the industry into uncharted waters, as it has many times in the past. Whether it is selecting specific raw materials for the brewing process, or processing aids or additives to enhance the specific brewing characteristics, it has always been and will always be in the brewer’s interest to maintain the integrity of his/her brand and products in line with consumer expectations and governmental regulations and specifications.

REFERENCES

1. Meussdoerffer, F.G., A comprehensive history of beer brewing, in Handbook of Brewing: Processes, Technology, Markets, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, pp. 1–42, 2009.

2. Anderson, R.G., History of industrial brewing, in Handbook of Brewing, 2nd ed., Priest F.G. and Stewart G.G., Eds., Taylor and Francis, Boca Raton FL, pp. 1–38, 2006.

3. McGrath, C., Ode to a can of Schaefer Beer, New England Review, 27:210–212, 2006.

4. Bruegel, P., The Peasant Dance, oil on canvas, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, c1569.

5. van Rijn, R., The Prodigal Son in the Tavern, oil on canvas, Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, c1635.

6. Singleton, H., The Ale-House Door, oil on canvas, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, ~1790.

7. Manet, E., A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, oil on canvas, Courtauld Gallery, London, c1882.

8. van Gogh, V., Beer Tankards, van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, 1885.

9. Picasso, P., Bottle of Bass and Glass, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, c1914.

10. Gromaire, M., The Beer Drinkers, Musee d’art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, c1924.

11. Bamforth, C.W., Beer and health, in Beer a Quality Perspective, Bamforth, C.W., Vol. Ed., Academic Press, London, pp. 229–254, 2011.

12. Morgan, C. J. and Badawy, A.A.B., Alcohol-induced euphoria: Exclusion of serotonin, Alcohol Alcohol., 36:22–25, 2001.

13. Vallee, B.L., Alcohol in the western world, Sci. Am., 278:80–85, 1998.

14. Menz, G., Aldred, P., and Vriesekoop, F., Pathogens in beer, in Beer in Health and Disease Prevention, Preedy, V.R., Ed., Elsevier Academic Press, Amsterdam, pp. 403–413, 2009.

15. Menz, G., Aldred, P., and Vriesekoop, F., Growth and survival of foodborne pathogens in beer, J. Food Prot., 74:1670–1675, 2011.

16. Menz, G., Vriesekoop, F., Zarei, M., Zhu, B., and Aldred, P., The growth and survival of food-borne pathogens in sweet and fermenting brewers’ wort, Int. J. Food Microbiol., 140:19–25, 2010.

17. Vriesekoop, F., Krahl, M., Hucker, B., and Menz, G., 125th Anniversary Review: Bacteria in brewing: The good, the bad and the ugly, J. Inst. Brew., 118:335–345, 2012.

18. Sicherer, S. H. and Sampson, H.A., Food allergy: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment, J. Allergy Clin. Immunol., 133:291–307, 2014.

19. Soller, L., Ben-Shoshan, M., Harrington, D.W., Knoll, M., Fragapane, J., Joseph, L., St Pierre, Y., La Vieille, S., Wilson, K., Elliott, S.J., and Clarke, A.E., Prevalence and predictors of food allergy in Canada: A focus on vulnerable populations, J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract., 3:42–49, 2015.

20. Versluis, A., Knulst, A.C., Kruizinga, A.G., Michelsen, A., Houben, G.F., Baumert, J.L., and van Os‐Medendorp, H., Frequency, severity and causes of unexpected allergic reactions to food: A systematic literature review, Clin. Exp. Allergy, 45:347–367, 2015.

21. Hadjivassiliou, M., Sanders, D.S., and Aeschlimann, D., The neuroimmunology of gluten intolerance, in Neuro-Immuno-Gastroenterology, Springer International Publishing, New York, pp. 263–285, 2016.

22. Cerf-Bensussan, N. and Meresse, B., Coeliac disease and gluten sensitivity: Epithelial stress enters the dance in coeliac disease, Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 12:491–492, 2015.

23. Ludvigsson, J.F., Leffler, D.A., Bai, J.C., Biagi, F., Fasano, A., Green, P.H., Hadjivassiliou, M., Kaukinen, K., Kelly, C.P., Leonard, J.N., and Lundin, K.E.A., The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms, Gut, 62:43–52, 2013.

24. Hager, A.S., Taylor, J.P., Waters, D.M., and Arendt, E.K., Gluten free beer–A review, Trends Food Sci. Technol., 36:44–54, 2014.

25. Dostálek, P., Hochel, I., Méndez, E., Hernando, A., and Gabrovská, D., Immunochemical determination of gluten in malts and beers, Food Addit. Contam., 23:1074–1078, 2006.

26. Guerdrum, L.J. and Bamforth, C.W., Levels of gliadin in commercial beers, Food Chem., 129:1783–1784, 2011.

27. Meo de, B., Freeman, G., Marconi, O., Booer, C., Perretti, G., and Fantozzi, P., Behaviour of malted cereals and pseudo‐cereals for gluten‐free beer production, J. Inst. Brew., 117:541–546, 2011.

28. van Zandijke, S., Gluten-reduced beers made with barley, The New Brewer, Nov./Dec. 79–84, 2013.

29. Walter, T., Wieser, H., and Koehler, P., Degradation of gluten in wheat bran and bread drink by means of a proline-specific peptidase, J. Nutr. Food Sci., 4:293, 2014, doi/10.4172/2155-9600.1000293.

30. van Landschoot, A., Gluten-free barley malt beers, Cerevisia, 36:93–97, 2011.

31. Kucek, L.K., Veenstra, L.D., Amnuaycheewa, P., and Sorrells, M.E., A grounded guide to gluten: How modern genotypes and processing impact wheat sensitivity, Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf., 14:285–302, 2015.

32. Boulton, C. and Quain, D., Brewing Yeast and Fermentation, Wiley-Blackwell, UK, 660p., 2006.

33. Walker, S., Camarena, M., and Freeman, G., Alternatives to isinglass for beer clarification, J. Inst. Brew., 113:347–354, 2007.

34. Hucker, B., Vriesekoop, F., Vriesekoop‐Beswick, A., Wakeling, L., Vriesekoop‐Beswick, H., and Hucker, A., Vitamins in brewing: Effects of post‐fermentation treatments and exposure and maturation on the thiamine and riboflavin vitamer content of beer, J. Inst. Brew, 122:278–288, 2016.

35. Baxter, E., Cooper, D., Fisher, G., and Muller, R., Analysis of isinglass residues in beer, J. Inst. Brew., 113:130–134, 2007.

36. Yildirim, H., Effects of fining agents on antioxidant capacity of red wines, J. Inst. Brew., 117:55–60, 2011.

37. Cosme, F., Ricardo-da-Silva, J. M., and Laureano, O., Interactions between protein fining agents and proanthocyanidins in white wine, Food Chem., 106:536–544, 2008.

38. André, F., Cavagna, S., and André, C., Gelatine prepared from tuna skIn: A risk factor for fish allergy or sensitization? Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol., 130:17–24, 2003.

39. Hansen, T.K., Poulsen, L.K., Skov, P.S., Hefle, S.L., Hlywka, J.J., Taylor, S.L., Bindslev-Jensen, U., and Bindslev-Jensen, C., A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled oral challenge study to evaluate the allergenicity of commercial, food-grade fish gelatine, Food Chem. Toxicol., 42:2037–2044, 2004.

40. EFSA – EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies on a request from the Commission related to a notification from Brewers of Europe and BFBi on isinglass used as a clarifying agent in brewing pursuant to Article 6 paragraph 11 of Directive 2000/13/EC—For permanent exemption from labelling, EFSA J., 536:1–10, 2007.

41. Directive 2003/89/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 November 2003 amending Directive 2000/13/EC as regards indication of the ingredients present in foodstuffs. Official Journal of the European Union, EFSA J., 308:15–18, 2003.

42. Lachenmeier, D.W. and Nerlich, U., Evaluation of sulphite in beer and spirits after the new allergen labelling rules, Brewing Sci., 59:114–117, 2006.

43. Van Leeuwen, T., A comparison of the chemical analysis of beers and judges’ scores from the 2004 Australian International Beer Awards, Honours thesis, University of Ballarat, 2006.

44. Ilett, D.R., Aspects of the analysis, role, and fate of sulphur dioxide in beer – A review, Tech. Q. Master Brew. Assoc. Am., 32:213–221, 1995.

45. Guido, L.F., Sulfites in beer: Reviewing regulation, analysis and role, Scientia Agricola, 73:189–197, 2016.

46. Brown, B.M., Oyster stout, J. Inst. Brew., 65:77, 1939.

47. Kokosinski, E., Improvement in the manufacture of beer. U.S. Patent 222,507, 1879.

48. Holsinger, V.H., Posati, L.P., and DeVilbiss, E.D., Whey beverages: A review, J. Dairy Sci., 57:849–859, 1974.

49. Dietrich, K.R., Whey-containing malt wort as a raw material for the preparation of a malt-whey beer, Brauwissenschaft, 2:26, 1949.

50. Brunner, R. and Vogl, A., The production of beer with the use of whey, Gambrinus, 5:181, 1944.

51. Pavsler, A. and Buiatti, S., Non-lager beer, in Beer in Health and Disease Prevention, Preedy, V.R., Ed., Elsevier Academic Press, Amsterdam, pp. 17–31, 2009.

52. Harding, L., Whey, Int. J. Dairy Technol., 16:53–61, 1963.

53. Rona, R.J., Keil, T., Summers, C., Gislason, D., Zuidmeer, L., Sodergren, E., Sigurdardottir, S.T., Lindner, T., Goldhahn, K., Dahlstrom, J., and McBride, D., The prevalence of food allergy: A meta-analysis, J. Allergy Clin. Immunol., 120:638–646, 2007.

54. Briggs, D.E., Brookes, P.A., Stevens, R., and Boulton C.A., Water, effluents and wastes, in Brewing: Science and Practice, Woodhead Publishing, UK, 848p., 2004.

55. Palmer, G.H., Barrett, J., and Kirsop, B.H., Combined acidulation and gibberellic acid treatment in the accelerated malting of abraded barley, J. Inst. Brew., 78:81–83, 1972.

56. Macey, A. and Stowell, K.C., Preliminary observations on the effect of potassium bromate in barley steep‐water, J. Inst. Brew., 63:391–396, 1957.

57. Dudley, M.J. and Briggs, D.E., Effects of bromate and gibberellic acid on malting barley, J. Inst. Brew, 83:305–307, 1977.

58. Parker, D.K. and Proudlove, M.O., Studies on the mechanisms of rootlet inhibition in developing barley embryos, J. Cereal Sci., 21:71–78, 1995.

59. Cantor, K.P., Feasibility of conducting human studies to address bromate risks, Toxicol., 221:197–204, 2006.

60. Moore, M.M. and Chen, T., Mutagenicity of bromate: Implications for cancer risk assessment, Toxicol., 221:190–196, 2006.

61. Kolisetty, N., Bull, R.J., Muralidhara, S., Costyn, L.J., Delker, D.A., Guo, Z., Cotruvo, J.A., Fisher J.E., and Cummings, B.S., Association of brominated proteins and changes in protein expression in the rat kidney with subcarcinogenic to carcinogenic doses of bromated, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 272:391–398, 2013.

62. Schuster, K., Malting technology, in Barley and Malt, Biology, Biochemistry, Technology, Cook, A.H., Ed., pp. 271–302, 1962.

63. Ling, A.R. and Newlands, B.E.R., Examination of fuels employed in malting, with special reference to the arsenic they contain, J. Fed. Inst. Brew., 7:314–337, 1901.

64. Duck, N.W. and Himus, G.W., On arsenic in coal and its mode of occurrence, Fuel, 30:267–271, 1951.

65. Ault, R., Determination of arsenic in malting coal, J. Inst. Brew., 67:14–28, 1961.

66. Wood Smith, R.F., and Jenks, R.L., A monthly record for all interested in chemical manufactures: Part 1, J. Soc. Chem. Ind., 20:417–466, 1901.

67. Vahidnia, A., van der Voet, G.B., and de Wolff, F.A., Arsenic neurotoxicity—A review, Hum. Exp. Toxicol., 26:823–832, 2007.

68. Hughes, M.F., Arsenic toxicity and potential mechanisms of action, Toxicol. Lett., 133:1–16, 2002.

69. Beaven, E.S., Fuel consumption in malt kilns, J. Inst. Brew., 10:454–480, 1904.

70. Pollock, J.R.A., Aspects of nitrosation in malts and beers. I. Examination of malts for the presence of N‐nitrosoproline, N‐nitrososarcosine and N‐nitrosopipecolinic acid, J. Inst. Brew., 87:356–359, 1981.

71. Havery, D.C., Hotchkiss, J.H., and Fazio, T., Nitrosamines in malt and malt beverages, J. Food Sci., 46:501–505, 1981.

72. Frommberger, R., N-nitrosodimethylamine in German beer, Food Chem. Toxicol., 27:27–29, 1989.

73. Spiegelhalder, B., Eisenbrand, G., and Preussmann, R., Contamination of beer with trace quantities of N-nitrosodimethylamine, Food Cosmet. Toxicol., 17:29–31, 1979.

74. Izquierdo-Pulido, M., Barbour, J.F., and Scanlan, R.A., N-nitrosodimethylamine in Spanish beers, Food Chem. Toxicol., 34:297–299, 1996.

75. Izquierdo-Pulido, M., Hernández-Jover, T., Mariné-Font, A., and Vidal-Carou, M.C., Biogenic amines in European beers, J. Agric. Food Chem., 44:3159–3163, 1996.

76. Lachenmeier, D.W. and Fügel, D., Reduction of nitrosamines in beer—Review of a success story, Brew Sci., 60:84–89, 2007.

77. Yurchenko, S. and Mölder, U., N-nitrosodimethylamine analysis in Estonian beer using positive-ion chemical ionization with gas chromatography mass spectrometry, Food Chem., 89:455–463, 2005.

78. Tricker, A.R. and Preussmann, R., Carcinogenic N-nitrosamines in the diet: Occurrence, formation, mechanisms and carcinogenic potential, Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol., 259:277–289, 1991.

79. Wainright, T., The chemistry of nitrosamine formation: Relevance to malting and brewing, J. Inst. Brew., 92:49–64, 1986.

80. Long, D.G., From cobalt to chloropropanol: De tribulationibus aptis cerevisiis imbibendis, J. Inst. Brew., 105:79–84, 1999.

81. Wainwright, T., Nitrosodimethylamine: Formation and palliative measures, J. Inst. Brew., 87:264–265, 1981.

82. Johnson, P., Pfab, J., Tricker, A.R., Key, P.E., and Massey, R.C., An investigation into the apparent total N‐nitroso compounds in malts, J. Inst. Brew., 93:319–321, 1987.

83. Schönberger, C., and Kostelecky, T., 125th Anniversary Review: The role of hops in brewing, J. Inst. Brew., 117:259–267, 2011.

84. Stubbs, B.J., 2003. Captain Cook’s beer: The antiscorbutic use of malt and beer in late 18th century sea voyages, Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr., 12:129–137.

85. Bonciu, C. and Stoicescu, A., Obtaining and characterization of beers with cherries, Innov. Rom. Food Biotechnol., 3:23–27, 2008.

86. Takoi, K., Itoga, Y., Koie, K., Kosugi, T., Shimase, M., Katayama, Y., Nakayama, Y., and Watari, J., The contribution of geraniol metabolism to the citrus flavour of beer: Synergy of geraniol and β‐citronellol under coexistence with excess linalool, J. Inst. Brew., 116:251–260, 2010.

87. Verachtert, H. and Derdelinckx, G., Belgian acidic beers daily reminiscences of the past, Cerevisia, 38:121–128, 2014.

88. Sharpe, F.R. and Crabb, D., Pilot plant extraction of hops with liquid carbon dioxide and the use of these extracts in pilot and production scale brewing, J. Inst. Brew., 86:60–64, 1980.

89. Menz, G., Andrighetto, C., Lombardi, A., Corich, V., Aldred, P., and Vriesekoop, F., Isolation, identification, and characterisation of beer‐spoilage lactic acid bacteria from microbrewed beer from Victoria, Australia, J. Inst. Brew., 116:14–22, 2010.

90. Suzuki, K., 125th Anniversary review: Microbiological instability of beer caused by spoilage bacteria, J. Inst. Brew., 117:131–155, 2011.

91. Zhao, X., Du, G., Zou, H., Fu, J., Zhou, J., and Chen, J., Progress in preventing the accumulation of ethyl carbamate in alcoholic beverages, Trends Food Sci. Tech., 32:97–107, 2013.

92. Weber, J.V. and Sharypov, V.I., 2009. Ethyl carbamate in foods and beverages: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett., 7:233–247, 2009.

93. Smythe, J.E., O’Mahony, M.A., and Bamforth, C.W., The impact of the appearance of beer on its perception, J. Inst. Brew., 108:37–42, 2002.

94. Smythe, J.E. and Bamforth, C.W., The path analysis method of eliminating preferred stimuli (PAMEPS) as a means to determine foam preferences for lagers in European judges based upon image assessment, Food Qual. Prefer., 14:567–572, 2003.

95. Callemien, D. and Collin, S., Involvement of flavanoids in beer color instability during storage, J. Agric. Food Chem., 55:9066–9073, 2007.

96. Suárez, A.F., Kunz, T., Rodríguez, N.C., MacKinlay, J., Hughes, P., and Methner, F.J., Impact of colour adjustment on flavour stability of pale lager beers with a range of distinct colouring agents. Food Chem., 125:850–859, 2011.

97. Bamforth, C.W., 125th Anniversary Review: The non‐biological instability of beer, J. Inst. Brew., 117:488–497, 2011.

98. Feilner, R. and Jacob, F.F., Improving resistance to aging and increasing haze stability in southern German wheat beer through process optimization, Monatsschr. Brauwiss., 68:58–66, 2015.

99. Bamforth, C.W., The foaming properties of beer, J. Inst. Brew., 91: 370–383, 1985.

100. Jackson, G., Roberts, R.T., and Wainwright, T., Mechanism of beer foam stabilization by propylene glycol alginate, J. Inst. Brew., 86:34–37, 1980.

101. Anderson, D.M.W., Brydon, W.G., Eastwood, M.A., and Sedgwick, D.M., Dietary effects of propylene glycol alginate in humans, Food Addit. Contam., 8:225–236, 1991.

102. Gultekin, F. and Doguc, D.K., Allergic and immunologic reactions to food additives, Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol., 45:6–29, 2013.

103. Sullivan, J.F., George, R., Bluvas, R., and Egan, J.D., Myocardiopathy of beer drinkers: Subsequent course, Ann. Int. Med., 70:277–282, 1969.

104. Rudin, A.D., Effect of nickel on the foam stability of beers in relation to their isohumulone contents, J. Inst. Brew., 64:238–239, 1958.

105. Evans, J.I., Control of beer foam, Process Biochem., 7:29–31, 1972.

106. Bishop, L.R., Whitear, A.L., and Inman, W.R., A scientific basis for beer foam formation and cling, J. Inst. Brew., 80:68–80, 1974.

107. Alexander, C.S., Cobalt-beer cardiomyopathy: A clinical and pathologic study of twenty-eight cases, Am. J. Med., 53:395–417, 1972.

108. Underwood, E., Cobalt, in Trace Elements in Human and Animal Nutrition, 4th ed. Elsevier, UK, pp. 132–158, 2012.

109. Kesteloot, H., Roelandt, J., Willems, J., Claes, J.H., and Joossens, J.V., An enquiry into the role of cobalt in the heart disease of chronic beer drinkers, Circulation, 37:854–864, 1968.

110. Lorca, T.A., Why should the malting and brewing industry be concerned about food safety? Part 1, Tech. Q. Master Brew. Assoc. Am., 53:34–38, 2016.

111. Bayne, P.D., Fluorocarbon gas as a foam improving additive for carbonated beverages, U.S. Patent, 3,515,560, issued June 2, 1970.