1

Background and Context

Introduction

The relationship between globalization and poverty is not well understood. For many, globalization is held out as the only means by which global poverty can be reduced. For others, globalization is seen as an important cause of global poverty. Consider the following two quotations:

A world integrated through the market should be highly beneficial to the vast majority of the world’s inhabitants.

While promoters of globalization proclaim that this model is the rising tide that will lift all boats, citizen movements find that it is instead lifting only yachts.

—International Forum on Globalization

To the knowledgeable global citizen, such disparate views are a cause of some confusion and concern. In this book, we aim to resolve this confusion. We want to provide an understanding of the main dimensions of economic globalization and their impact on poverty and development. Although rooted in rigorous inquiry, this is not narrowly an academic book. Our objective is to inform the wider public and to provide a broad foundation for policy discussions on globalization and poverty.

Many claims about the relationship between globalization and poverty are not well founded. By examining both the processes through which globalization takes place and the effects that each of these processes can have on global poverty alleviation, current discussions can be better informed. The processes we examine in this book constitute the main global economic channels affecting poverty: trade, finance, aid, migration, and ideas.1 By considering each of these processes, confusion about globalization can, to some extent at least, be resolved. To that end, this chapter introduces the five dimensions of globalization and considers the problem of global poverty, placing both globalization and poverty in historical context. Our central message is that, with appropriate national and global policies, globalization can be an important catalyst for alleviating global poverty. In the absence of these policies, however, this catalyst role is diminished. In a few particular instances, globalization without corrective policies can actually exacerbate certain dimensions of poverty. We identify what actions are needed to produce positive global outcomes.

Globalization and Global Poverty

Globalization is an often-discussed but seldom-defined phenomenon. At a broad level, globalization is an increase in the impact on human activities of forces that span national boundaries. These activities can be economic, social, cultural, political, technological, or even biological, as in the case of disease. Additionally, all of these realms can interact. For example, HIV/AIDS is a biological phenomenon, but it affects and is affected by economic, social, cultural, political, and technological forces at global, regional, national, and community levels. In this book, we focus primarily on economic activities, referring to the other realms of globalization only tangentially.2 This no doubt reflects our bias as economists, but also our observation that global poverty is very much (but certainly not exclusively) an economic phenomenon. In adopting this economic focus, we in no way wish to imply that social, cultural, political, technological, and biological aspects of globalization are unimportant. They are important. But having cast our net widely already to include multiple dimensions of economic globalization, we consider it unwise to cast it even more broadly.

The changing natures and qualities of the five economic dimensions of globalization characterize its process. These dimensions are

- trade

- finance

- aid

- migration

- ideas.

Trade is the exchange of goods and services among countries. Finance involves the exchange of assets or financial instruments among countries. Aid involves the transfer of loans and grants among countries, as well as technical assistance for capacity building. Migration takes place when persons move between countries either temporarily or permanently, to seek education and employment or to escape adverse political environments. Ideas are the broadest globalization phenomenon. They involve the generation and cross-border transmission of intellectual constructs in areas such as technology, management, or governance.

Key Terms and Concepts

autarky

bond finance

capacity building

capital flows

commercial bank lending

comparative advantage

equity portfolio investment

foreign direct investment (FDI)

global public good

gross domestic product (GDP)

migration

poverty

purchasing power parity dollars

Dimensions of Poverty

For each of these five economic dimensions of globalization, the field of investigation is very wide. We will narrow it significantly by considering only those aspects that are most closely tied to issues of poverty alleviation. This process of narrowing our scope requires a large element of judgment. In choosing what to emphasize, we have reflected the issues and concerns of development policy communities as well as our disciplinary backgrounds in economics.

What do we mean by global poverty? Although we all have some concept of what it is to be “poor,” the notion of poverty is not as straightforward as it might first appear. The reason is that poverty is not a one-dimensional phenomenon. It is multi-dimensional. A number of different concepts and measures of poverty relate to its various dimensions. Each of these dimensions has the common characteristic of representing deprivation of an important kind. The variety of poverty concepts in use in development policy communities reflects the variety of relevant deprivations.3 The major measures of poverty we consider here are those that encompass:

- income

- health

- education

- empowerment

- working conditions.

Income

The most common measure of poverty is known as income poverty, and it derives from a conception of human well-being defined in terms of the consumption of goods and services. In this approach, poverty is viewed as a lack of goods consumption due to a lack of necessary income. At present, the most widely accepted measure of income poverty is in terms of one or two U.S. dollars per day, measured in constant (price adjusted), “purchasing power parity” dollars.4 Individuals who exist on less than one dollar a day are known as the “dollar poor” or the “extremely poor”; individuals who exist on less than two dollars a day are known as the “poor.”5 In this book, we use this concept as one important indicator of global poverty.

Health

There is growing recognition that income poverty is not the only important measure of deprivation.6 For example, poor health is now recognized as perhaps the most central aspect of poverty. The fact that 6 million persons die annually from AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria illustrates this point, as do the annual deaths of a roughly equal number of infants from largely preventable causes such as diarrheal disease. Health deprivation characterizing poverty can be assessed in terms of life expectances, infant and child mortality, and a number of other health-related measures.

Education

Lack of education that results in limited literacy and numeracy is another important deprivation. Indeed, lack of education is often an important cause of deprivations in income and health. This dimension of poverty can be assessed in terms of literacy rates, average years of schooling, or enrollment rates. Gender disparities in education are an important and too-often-observed component of educational deprivation and represent a key obstacle to development.

Empowerment

Lack of what is sometimes called “empowerment” is a fourth important dimension of poverty. This includes limits on individuals’ abilities to enter into and participate in social realms such as work and political processes because of discrimination of various kinds. Gender disparities are an important kind of empowerment deprivation and interact in detrimental ways with consequences in health and educational deprivations. In many countries, for example, women are socially restricted from entering the workforce or from political participation. In some instances, they do not have the same legal rights as men.7

Working Conditions

One important issue that does not always arise in discussions of poverty concepts is working conditions. As emphasized by Bruton and Fairris (1999), “Because a person fortunate enough to have a full-time job will spend at least one half of his/her waking hours at work, it is incumbent on social scientists to investigate the conditions necessary for the maintenance of working conditions that are safe and pleasant and for the creation of jobs that contribute to individual and social well-being” (p. 6). We will turn to these working-condition issues at various junctures in this book, especially to considerations of forced labor, health, and safety.8

Assessment of Dimensions of Poverty

Each of these dimensions of poverty can be assessed in absolute or in relative terms.9 For example, income poverty can be assessed in terms of the numbers of individuals living below an income level (absolute) or in terms of the lowest 20 percent of households ranked according to income (relative). Both absolute and relative poverty are important for social outcomes. In this book, however, we will place a greater emphasis on absolute poverty. With regard to income poverty, we will emphasize the “dollar a day” or “extreme” poor measure. With regard to other dimensions of poverty, we will emphasize illiteracy (including gender disparities) and infant mortality. The ways in which globalization as described above plays a positive or negative role in such poverty alleviation is our central concern here.

A Historical View

Both globalization and poverty have deep historical roots. Although in popular accounts globalization is a recent phenomenon, historians recognize that, in some important respects, it is not new. The ever-increasing integration of people and societies around the world has been both a cause and an effect of human evolution, proceeding more in fits and starts than in any simple, linear progression. Technological innovations, whether in the form of the marine chronometer or modern fiber optics, have propelled surges in globalization; changes in policy, institutions, or cultural preferences have restrained or even reversed it. In the 15th century, for instance, the Chinese emperor Hung-hsi banned maritime expeditions, slowing down Asian globalization considerably.10 Similarly, the proliferation of nation states and the imposition of border controls in the early 20th century generated new obstacles to the movement of goods, capital, persons, and ideas among the countries of the world.

Stages of the Modern Era of Globalization

Economic historians date the modern era of globalization to approximately 1870. The period from 1870 to 1914 is often considered to be the birth of the modern world economy, which, by some measures, was as integrated as it is today. A description of this world by John Maynard Keynes can be found in box 1.1. What historians have observed is that, from the point of view of capital flows (the predominately British foreign direct investment and portfolio investment of the era), the late 1800s were an extraordinary time.11 The global integration of capital markets was facilitated by advances in rail and ship transportation and in telegraph communication. European colonial systems were at their highest stages of development, and migration was at a historical high point in relation to the global population of the time.

Box 1.1 John Maynard Keynes on Globalization

Looking back on the end of the 19th century, and writing in 1919, John Maynard Keynes described the vanishing world of the British economic empire as follows:

The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep; he could at the same moment and by the same means adventure his wealth in the natural resources and new enterprises of any quarter of the world, and share, without exertion or even trouble, in their prospective fruits and advantages; or he could decide to couple the security of his fortunes with the good faith of the townspeople of any substantial municipality in any continent that fancy or information might recommend. He could secure forthwith, if he wished it, cheap and comfortable means of transit to any country or climate without passport or other formality, could despatch his servant to the neighbouring office of a bank for such supply of the precious metals as might seem convenient, and could then proceed abroad to foreign quarters, without knowledge of their religion, language, or customs, bearing coined wealth upon his person, and would consider himself greatly aggrieved and much surprised at the least interference. But, most important of all, he regarded this state of affairs as normal, certain, and permanent, except in the direction of further improvement, and any deviation from it as aberrant, scandalous, and avoidable.

Source: Keynes 1920, pp. 11–12.

This first modern stage of globalization was followed by two additional stages, one from the late 1940s to the mid-1970s and another from the mid-1970s to the present. These, however, were preceded by World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II. During this time, many aspects of globalization were reversed as the world experienced increased conflict, nationalism, and patterns of economic autarky. To some extent, then, the second and third modern stages of globalization involved regaining lost levels of international integration.

The second modern stage of globalization began at the end of World War II. It was accompanied by a global, economic regime developed by the Bretton Woods Conference of 1944 establishing the International Monetary Fund (IMF), what was to become the World Bank, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) (see box 1.2). This stage of globalization involved an increase in capital flows from the United States, as well as a U.S.-founded production system that relied on exploiting economies of scale in manufacturing and the advance of U.S.-based multinational enterprises.12 This second stage also involved some reduction of trade barriers under the auspices of GATT. Developing countries were not highly involved in this liberalization, however. In export products of interest to developing countries (agriculture, textiles, and clothing), a system of nontariff barriers in rich countries evolved. Also, a set of key developing countries, especially those in Latin America, pursued import substitution industrialization with their own trade barriers.13 These developments, along with the Cold War, suppressed the integration of many developing countries into the world trading system.

Box 1.2 International Agreements, Institutions, and Key Players

The Bretton Woods Conference was a gathering of world leaders that took place in 1944 in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United States, with the aim of placing the international economy on a sound footing after World War II. The conference resulted in the establishment of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Institutions

The World Bank Group and the International Monetary Fund are sometimes referred to as the Bretton Woods Institutions.

The five World Bank Group institutions are as follows:

- The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) lends to governments of middle-income and creditworthy low-income countries.

- The International Development Association (IDA) provides interest-free loans, called credits, to governments of the poorest countries.

- The International Finance Corporation (IFC) lends directly to the private sector in developing countries.

- The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) provides guarantees to investors in developing countries against losses caused by noncommercial risks.

- The International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) provides international facilities for conciliation and arbitration of investment disputes.

The International Monetary Fund is a subscription-based, global financial organization whose purpose is to promote international monetary cooperation and the multilateral system of payments. It engages in four areas of activity: surveillance or monitoring, the dispensing of policy advice, lending, and providing technical assistance.

Other international economic institutions include the following:

- Nongovernmental Organizations (NGOs): Private, nonprofit organizations that pursue activities to relieve suffering, promote the interests of the poor, protect the environment, provide basic social services, or undertake community development. NGOs often differ from other organizations in the sense that they tend to operate independently from government, are values-based, and are guided by the principles of altruism and voluntarism.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): An international organization, primarily of high-income countries, helping governments tackle the economic, social, and governance challenges of a globalized society.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): Manages a “network” of development activities undertaken by the United Nations in the areas of democratic governance, poverty alleviation, crisis prevention and recovery, energy and the environment, and HIV/AIDS.

- World Trade Organization (WTO): An international organization governing the system of rules for global trade among its member nations. It is also involved in dispute settlement and compliance monitoring related to international trade.

Source: World Bank Group institutions: adapted from The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development 2003: box 1.1; other institutions: World Health Organization 2001b.

The third modern stage of globalization began in the late 1970s. This stage followed the demise of monetary relationships developed at the Bretton Woods Conference and involved the emergence of the newly industrialized countries of East Asia, especially Japan, Taiwan (China), and the Republic of Korea. Rapid technological progress, particularly in transportation, communication, and information technology, began to dramatically lower the costs of moving goods, capital, people, and ideas across the globe. For example, as noted by Frankel (2000), “Now fresh-cut flowers, perishable broccoli and strawberries, live lobsters and even ice cream are sent between continents” (pp. 2–3).14

Assembly systems in this latest stage of globalization were also significantly modified into a new arrangement characterized by flexible manufacturing. In flexible manufacturing systems, information technology supports computer-aided production and relies less on economies of scale. In this stage, Japan emerged as an important, new source of foreign direct investment (FDI): between 1960 and 1995, Japan’s share of global FDI increased from less than 1 percent to over 10 percent.15 The thawing of the Cold War, the entry of China into the world economy, and a general reduction of trade barriers in most developing countries beginning in the late 1980s, helped to accelerate global integration during this phase.

Modern Globalization and Global Poverty

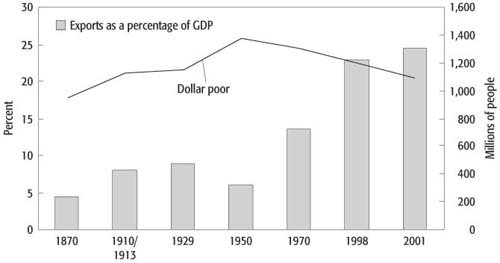

What has been the historical relationship between globalization and poverty during these three stages? A partial view is found in figure 1.1. This figure combines a single measure of globalization—exports as a percentage of world gross domestic product (GDP), with a single measure of poverty—the number of dollar (extreme) poor people, in a time series from 1870 to 1998. What is clear from this schematic is that, historically, globalization and global poverty can be either positively related or negatively related to each other. From 1870 though 1929 and the beginning of the Great Depression, globalization (trade) and global poverty increased together. However, the retreat from globalization during the Great Depression and World War II was accompanied by a continued increase in global poverty. This can be seen from the 1950 data in figure 1.1 showing that, when exports as a percentage of GDP had declined nearly back to the 1870 level, extreme poverty reached a peak of approximately 1.4 billion persons (a billion is 1,000 million).

Figure 1.1 Trade and Extreme Poverty in Historical Perspective

Source: Exports as a percentage of GDP from Ocampo and Martin (2003) based on Maddison (2001) and from World Bank (2004d). Dollar poor data from Bourguignon and Morrisson (2002), and Chen and Ravallion (2004).

As seen in figure 1.1, the increase in globalization as measured by trade in the second and third stages of modern globalization has been associated with a gradual decline in extreme poverty to approximately 1.1 billion people. During these stages, globalization and poverty have been negatively associated with each other, albeit mildly so. A key public policy challenge facing humankind is to eliminate this still-prominent level of extreme poverty. Understanding how to do this requires a deeper understanding of the links between globalization and poverty.

The Globalization-Poverty Relationship

As mentioned above, globalization has the five primary economic dimensions trade, finance, aid, migration, and ideas. Increases in these dimensions of globalization, if managed in a way that supports development in all countries, can help to alleviate global poverty under certain conditions. We investigate these pathways and conditions in some detail later in this book. We also consider some particular circumstances where dimensions of globalization can aggravate some dimensions of poverty. Here we define and summarize the five economic dimensions of the relationship between globalization and poverty.

Trade

Trade is the exchange of both goods and services among the countries of the world economy.16 The involvement of developing countries as exporters in global trade has increased significantly since the mid-1980s, even in services where their comparative advantage is typically seen as weak. For a variety of reasons (not least the trade barriers placed by rich countries), the agricultural exports of the developing world have been stagnant. The regional involvement of developing countries in trade varies widely, with Africa’s share of world exports declining over time.

Increased international trade can help to alleviate poverty through job creation, increased competition, improvements in education and in health, and technological learning. The impact of increasing trade openness depends critically on the relationship between trade reforms and other reforms and complementary actions at the national and international levels. Increased exports of petroleum and minerals often (but not always or necessarily) fail to support these activities, as many developing countries have found. Many kinds of manu-facturing, agricultural, and service exports, accompanied by complementary infrastructure and training policies, can support these activities, however. In addition, imports of many types—especially health-related imports and imports embodying new technologies—are crucial for alleviating poverty.

The exports of developing countries face many kinds of protective barriers, including tariffs, subsidies, quotas, standards and regulations, and increasing security checks. Rich-world agricultural subsidies, for example, are twice as large as the entire agricultural exports of all developing-country exports combined and six times the value of foreign aid. These subsidies have exceeded the entire GDP of Sub-Saharan Africa in recent years and reducing protection is vital for more inclusive globalization. Conservative estimates suggest that limited trade liberalization could reduce the number of poor people (those who live on US$2 per day) by a minimum of 100 million.17

For any increase in market access for developing country exports to positively affect poor people, trade-related capacity building is necessary, particularly to support the diversification of exports away from standard primary products. This is an important area where the trade and foreign aid dimensions of globalization can complement each other. To protect the most vulnerable who can sometimes lose as a result of trade liberalization, social safety nets and complementary antipoverty programs are crucial.18

Finance

Global finance in the form ofcapital flows involves the exchange of assets or financial instruments among the countries of the world, either by private or public agents. In this book, we distinguish among four types of capital flows:

- foreign direct investment or FDI

- equity portfolio investment

- bond finance

- commercial bank lending.

Foreign direct investment (FDI ) is defined here as the acquisition of part of a foreign-based enterprise that exceeds a threshold of 10 percent, implying managerial participation in the foreign enterprise. Equity portfolio investment is similar to FDI in that it involves the ownership of shares in foreign enterprises. It differs from FDI, however, in that the share holdings are too small to imply managerial participation in the foreign enterprise. It is thus indirect rather than direct investment, undertaken for portfolio reasons rather than for managerial reasons. Its behavior can consequently differ substantially from that of FDI.

Bond finance (also called debt issuance) is a second kind of portfolio activity. It involves governments or firms issuing bonds to foreign investors. These bonds can be issued in either the domestic currency or in foreign currencies, and they carry a number of types of default risk. Both bond finance and equity portfolio investments are held by domestic and international investors as a way to manage wealth, and the entire range of portfolio behaviors apply to both. Commercial bank lending is another form of debt, but it does not involve a tradable asset as bond finance does.19

Private capital flows to developing countries have increased significantly since the early 1990s, particularly in the case of FDI, which has displaced the previously dominant commercial bank lending in importance. Equity portfolio investment and bond finance flows to developing countries, however, have been volatile since the 1997 Asian crisis, although both have recovered somewhat in recent years. Official capital flows, reflecting the activities of central banks, are a different story. Since 2000, the government and trade deficits of the United States have involved that country importing over US$500 billion in recent years, structurally claiming the bulk of world savings, which is provided in part by Asian central banks buying U.S. government debt. As a result of these official transactions, the developing world has recently become a net exporter of capital.

From the point of view of alleviating poverty, capital flows have both significant promise and some particular dangers. Capital flows can help to mobilize and deploy savings, develop the financial sector, and transfer technology. They can also manage various types of risk and channel funds in line with the performance of firms’ managers. The financial markets involved in some kinds of capital flows, however, are characterized by a number of imperfections that economists refer to as “market failures.” In particular, information is less than perfect in these markets, and this can cause significant volatility in flow levels. Consequently, deepening and regulating these flows poses considerable policy challenges.

Foreign direct investment can contribute to poverty alleviation when it supports the generation of new employment, promotes competition, improves the education and training of host-country workers, and transfers new technology. These benefits are evident in a host of developing countries. Unfortunately, FDI is highly concentrated, and many developing countries receive little or no FDI inflows. FDI that establishes backward links to local suppliers and advances best practices in terms of technology, employment, and social conditions is more beneficial than FDI that remains a low-wage enclave within the host country.

Equity portfolio investment, bond finance, and commercial bank lending can help to alleviate poverty under effective exchange rate regimes and properly regulated and developed financial systems. Equity portfolio investment, in particular, has been positively associated with growth through its support of entrepreneurial activity.20 Bond finance and commercial bank lending can leave developing countries vulnerable to crises that arise from the volatile nature of portfolio investment. Such crises can increase poverty substantially, as happened in Asia during the late 1990s.21 Properly managed, however, bond finance and commercial bank lending can be an important part of financial sector development. This aspect of economic globalization, then, must be handled with care.

Aid

Aid is the transfer of funds in the form of some combination of loans or grants and the provision of technical assistance or capacity building. The transfer of funds can be in the form of bilateral aid between two countries or in the form of multilateral aid that is channeled through organizations such as the World Bank. Foreign aid remains a vital resource flow for many developing countries. It can finance investment in infrastructure and services, supplement capabilities in health and education, and provide access to new ideas in the realm of policy. These characteristics make it possible for aid to have a significant impact on global poverty alleviation. The motivations of foreign aid donors have varied widely and include advancing geopolitical objectives, stimulating economic development, ameliorating poverty and suffering, promoting political outcomes, and ensuring civil stability and equitable governance. Given both these mixed objectives and the low quality of some developing country governance systems, aid has not always been effective.

That said, with the end of the Cold War calculus of donors and a greater emphasis on governance in the developing world, evidence that aid is more effective now than ever before is continuing to emerge.22 Sustaining the positive impact of aid requires both increasing aid flows and using them better. Despite the progress made in aid effectiveness, the share of the budgets that rich countries have devoted to aid declined during the last few decades, going from slightly over 0.35 percent of high-income countries’ GDP to approximately 0.25 percent only to rise again to over 0.30 percent in 2005. Only 5 of the 22 high-income countries of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee that have pledged 0.7 percent of their GDP to foreign aid have actually met this goal as of 2005.23 Indeed, foreign aid has steadily remained at approximately one-sixth of rich-world agricultural subsidies—subsidies that have been shown to significantly worsen global poverty. Recent evidence of a pick-up in aid volumes must be sustained if aid is to fulfill its potential in global poverty reduction.

Compared with private investment, and even with remittances, the value of aid flows is and will remain small. Domestic investment in developing countries is around US$1.5 trillion, much larger than aid levels that over the past decade averaged around US$63 billion per year and foreign investment of around US$200 billion. Recently, a renewed commitment to aid is evident in sharp increases in aid levels and promises. As we show, what matters most in foreign aid are the accompanying ideas, policies, and capacity building. These can increase the overall domestic and foreign investment flows that create jobs and drive sustainable growth and poverty alleviation. A persistent and important challenge for foreign aid is assisting weak or even failed states. These countries often vary widely in their problems, and approaches that work in a “typical” low-income country might not be effective. Large-scale financial transfers are unlikely to work well, and emphasis should be placed on capacity building to facilitate change, as well as on a limited reform agenda, stressing governance, basic health, educational services, and infrastructure.

Migration

We define migration as the temporary or permanent movement of persons between countries to pursue employment or education (or both) or to escape adverse political climates. In this book, we do not consider rural-urban and other sorts of migration within countries. Migrants can be categorized into permanent settlers, high- and low-skill expatriates, asylum seekers, refugees, undocumented workers, visa-free migrants, and students. Migration has historically been the most important means for poor people to escape poverty. Indeed, by some estimates, 10 percent of the world’s population permanently relocated between 1870 and 1910 during the first phase of modern globalization described above.24 This historical pattern has been greatly reduced by the development of nation states; more recently, at the beginning of the 20th century, it has been further reduced by the use of passports and a growing range of mechanisms to identify and control individual movement. Consequently, migration is much less free but is no less important for poverty alleviation.

In addition to the direct “escape from poverty” function, migrants also provide significant remittance flows to their families in their home countries. These remittance inflows, were approximately US$200 billion to developing countries in 2006, and exceed inflows of FDI in some regions by substantial amounts. On the other hand, migration also causes what is known as “brain drain”—the loss of educated and high-skilled citizens to other countries. The effective management of global migration flows is a difficult and controversial, but very important, challenge for the world community.

Current migration restrictions give rise to criminal activity and the exploitation of unsuspecting illegal migrants, often with tragic consequences. Skill poaching by wealthy countries can also have detrimental effects, not least in the health service area. As in the case of capital flows, migration must be managed carefully—preferably through multilateral frameworks.

The dearth of empirical research on key dimensions of migration makes forming policy on this subject particularly hazardous. However, there is one largely unexploited way for migration to positively affect global poverty. This is through the further development of the temporary movement of workers in services trade.25 These labor-intensive exports of services through the temporary movement of persons have the potential to allow developing countries to benefit from global services trade in a manner similar to the developed countries in other modes of service delivery, namely FDI in financial services and the temporary movement of corporate personnel. Significant further progress is necessary in this area.26

Ideas

Ideas are the most powerful influence on development. Ideas are the generation and transmission of distinctive intellectual constructs in any field that can have an impact on production systems, organizational and management practices, governance practices, legal norms, and technological trends. One well-known category of ideas is intellectual property, which can be thought of as an asset defined by legal rights conferred on a product of invention or creation.27 Ideas are not just commercial, however. For example, the notion of human rights that need to be respected and protected by governments is an idea of paramount importance. Additionally, flows of ideas across borders play an important role in shaping policies, as well as the perceptions and reality of poverty. In this book, we concentrate on ideas that shape economic activities rather than on those that have primarily cultural or political content, although we are mindful that these are distinctions mostly of convenience and need to be treated with care.

The evaluation and adaptation of ideas requires local capacity in the form of both skills and institutions, as well as a culture of learning. Developing countries can bridge existing gaps in knowledge by acquiring, absorbing, and communicating knowledge.28 Openness to ideas has historically been and continues to be an important way to alleviate poverty.29 Ideas can affect poverty through a variety of mechanisms and can interact in important ways with all of the other dimensions of economic globalization. More effective policy regimes, better technological innovations, greater respect for human rights, and the improved social status of women can all help the lives of poor people. The challenge in harnessing ideas to alleviate poverty lies in adapting them to the many local sociocultural contexts of the developing world. A full understanding of this challenge is still in progress, but it is clear that supporting the exchange of ideas and learning is vital to accelerating the beneficial impact of globalization.

The development community’s understanding of the most effective way to achieve development objectives has evolved over time with the accumulation of evidence and experience. Approaches that appeared at the time to be both correct and obvious have been undermined by experience and closer analysis. This has seen the broadening and deepening of what is meant by “development,” from income to include health, opportunity, and rights. Recent years have seen a greater recognition in the policy debate of the complementarities between markets and governments. Clearly, experience shows that the private market economy must be the engine of growth, but it shows also that a vibrant private sector depends on well-functioning state institutions to build a good investment climate and deliver basic services competently. Indeed, in many crucial areas—such as health, education, and infrastructure—public-private partnership is essential.

Areas for Action

History and the recent experiences of many countries have taught us that global integration can indeed be a powerful force for reducing poverty and empowering poor people. Poor people are less likely to remain poor in a country that is exchanging its goods, services, and ideas with the rest of the world. Yet, although participation in the global economy has generally been a powerful force for reducing poverty, the reach and impact of globalization remains uneven. In addition, the accelerated pace of globalization has been associated with a rapid rise in global risks, which have outpaced the capacity of global and national institutions to respond. The increasing global impact of national policies, ranging from armaments and contributions to climate change, points to the need for more effective global governance. If the globalization train is to pull all citizens behind it, policies that ensure that the poor people of the world share in its benefits are required.

In our concluding chapter, we draw together the many issues considered in this book and provide a policy agenda designed to ensure that increased globalization assists in alleviating poverty. Here we anticipate that more detailed discussion by briefly distilling four basic areas for action to support positive global outcomes. These are areas designed to accomplish the following:

- to ensure that global trade negotiations allow more equitable access to products of developing countries to the world market

- to increase aid, assistance, and debt relief to countries that demonstrate commitment to its effective use

- to enhance the benefits of migration and mitigate its harmful effects

- to support and encourage the development of global public goods to benefit poor people.

Balanced Outcomes to Global Trade Negotiations

The first area for action is ensuring that global trade negotiations yield more balanced outcomes. Rich countries must stop impeding the ability of poor countries to produce and trade a wide range of goods and services. Goods produced by poor people face, on average, double the tariff barriers of those produced in the most advanced countries. The practice of generously subsidizing agricultural production, a practice that is widespread in many high-income countries, has had a devastating impact on many poor producers, denying them not just export markets but also hindering their capacity to sell their produce in their own country. With around US$300 billion per year devoted to agricultural protection alone, the rich countries’ policies have created a fundamentally unbalanced playing field. Current policies compound the downward trend in commodity prices, increase instability, and undermine the potential for diversification into higher value added manufactured products. Reforming the world trade system and ensuring more equitable access for the products of poor countries is an essential step toward allowing more of the world’s people to enjoy the benefits of globalization.

Increase Aid, Assistance, and Debt Relief

The second area for action is the increased provision of aid, assistance, and debt relief to countries that demonstrate a commitment to the effective and equitable use of the additional resources. As mentioned above, aid volumes have declined during recent decades to approximately 0.25 percent of high-income countries’ GDP, despite the fact that donor countries are richer now than ever before and that aid has never been more effectively used. With the ending of the Cold War, aid has been increasingly allocated to countries able to use it most effectively. Not surprisingly, the impact of aid on growth and poverty reduction has more than doubled over recent years.30 Providing increased foreign assistance and implementing more rigorous schemes that monitor and evaluate the effective use of that aid are thus critical to ensuring that the gains provided by globalization are not erased by bad governance and ineffective use of aid.

Foreign aid resource transfers are particularly important in the poorest countries, and much higher levels of aid are urgently required for investments in health, education, infrastructure, and for combating HIV/AIDS and other diseases. These investments cannot be financed by domestic savings alone, especially in countries that are currently crushed under burdens of debt and escaping the ravages of past corruption and mismanagement.

Enhance the Benefits and Mitigate the Negative Effects of Migration

The third area for action is enhancing the benefits and mitigating the negative effects of migration. Migration remains for many poor people the most effective way to escape poverty. Recorded remittances of over US$150 billion are more than twice the amount of annual foreign assistance. Whereas barely 20 percent (averaging around US$10 billion over the past decade) of aid is transferred to developing countries in the form of resource transfers, the entirety of remittance flows represents real transfers. These flows could be increased if the transactions costs were reduced from their current average of up to 15 percent of the flows to around 1 percent, which is closer to the cost of transfers between rich countries. While foreign aid goes to governments and FDI flows to a small number of firms, remittances tend to flow directly to a large number of individuals and communities. The loss of skills associated with migration is a severe problem, not least for poor regions such as Africa or the Caribbean, where it is estimated that up to two-thirds of the educated doctors and teachers have left. Positive flows include the ideas and investments that originate with these diasporas, as is evident in the pivotal role of Indian emigrants in the Bangalore information technology boom. Addressing the problems of the current migration system and increasing its ability to provide real gains to poor people will require a multilateral as well as bilateral commitment to effective migration reform and management.

Support of Global Public Goods

The fourth area for action is support for what is commonly referred to asglobal public goods.31 Foremost among these global public goods is the need for global peace and stability. Conflicts lead to reverse development. Wars, big and small, destroy the foundation of growth and development and have a particularly devastating effect on poor people, especially poor children. Although many wars have local origins, they feed off global flows—from the sale of commodities such as diamonds and oil to the trade in arms and ammunition. Managing the wide range of environmental side effects associated with domestic policies is also vital. Chief among these environmental concerns are climate change and the looming water and energy crises, which will have increasing international dimensions. How these crises are managed are among the biggest development challenges facing our planet.

Another crucial global public good involves the management of science and technology in favor of development. Combating diseases, not least HIV/AIDS and malaria, as well as developing higher yield and stress-resistant crops can be addressed only at the global level, and requires a pooling of resources and the management of intellectual property and technology to overcome the widening scientific and digital divides.

The Purpose of this Book

The purpose of this book is to provide an understanding of the main aspects of economic globalization and their impact on poverty and development. By examining these dimensions in some detail, we hope to resolve to some extent the confusion about globalization represented in the quotations at the beginning of this chapter. In our view, globalization can be managed so that its benefits are more widely shared than they are today and so that its negative impacts are identified and mitigated. Achieving these outcomes is a global, national, and local responsibility. In the following chapters, we analyze the dimensions of this responsibility.

Notes

1. Clearly, our coverage is not comprehensive. We do not examine questions of culture, peace, politics, natural disasters, and security, nor global environmental and health issues, except where they are related to one of our primary areas of focus.

2. We are mindful of Gilpin’s (2000) statement that “No … book … can do justice to either the scope or the rapidity of the economic, political, and technological developments transforming human affairs” (p. ix). For an effort complementary to ours, see World Commission on the Social Dimension of Globalization (2004).

3. For a discussion of this variety, see chapter 4 of Sen (1999).

4. Purchasing power parity dollars adjust for differences in the cost of living among the countries of the world. This adjustment is especially important because nontraded services tend to be less expensive at low levels of income.

5. See Bourguignon and Morrisson (2002), Chen and Ravallion (2001), and Chen and Ravallion (2004) on the extent of poverty.

6. Again, see chapter 4 of Sen (1999).

7. See Nussbaum (2000) for a powerful, book-length discussion of the lack of empowerment of women in developing countries. Nussbaum notes the often-mentioned fact that “gender inequality is strongly correlated with poverty” (p. 3). See also World Bank (2005d)World Development Report on Equity and Development, which stresses the importance of equity and opportunity.

8. To mention just one example, the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture has estimated that well over 150,000 children are involved in hazardous labor in the cacao farms of West Africa, including clearing brush with machetes and applying pesticides, as part of the region’s export agriculture. See IITA (2002).

9. See, for example, Fields (2001).

10. Indeed, by 1500 in China, building ships with more than two masts was punishable by death.

11. See, for example, chapter 1 of James (1996), O’Rourke and Williamson (1999), and World Bank (2002c).

12. This production system is known as “Fordism” or “managerial capitalism.” To quote John and others (1997), “American corporations consolidated into the position of world leaders across almost the entire range of the advanced industries during the 1950s” (p. 40).

13. See Bruton (1998) for a review of import substitution industrialization.

14. With regard to declines in transportation costs, Frankel (2000) takes up the case of shipping costs. He notes that “The margin for US trade fell from about 9½ percent in the 1950s to about 6 percent in the 1990s” (p. 10). Here Frankel measures shipping cost margins as the ratio of c.i.f. (cost insurance freight) trade value to f.o.b. (free on board) trade value.

15. See Dicken (1998). This new production system is known as “Toyotism.”

16. Goods (or merchandise) are tangible and can be stored over time in inventories, while services are less tangible and cannot be stored. As is often remarked jokingly, you cannot drop a service on your toe. Consequently, the production and consumption of a service happens more or less simultaneously.

17. See World Bank (2003a).

18. This point is made by Winters, McCulloch, and McKay (2004).

19. Commercial bank loans, including interbank loans, can be short term or long term and can be made with fixed or flexible interest rates. A single bank or a syndicate of banks can be involved in any particular loan package.

20. See Rousseau and Wachtel (2000) for a discussion of how equity portfolio investment supports entrepreneurial activity.

21. Eichengreen (2004) notes that an “average” or “typical” financial crisis can claim up to 9 percent of GDP. Some of the worst crises, such as those in Argentina and Indonesia, reduced GDP by over 20 percent, declines greater than occurred in the United States during the Great Depression. Suryahadi, Sumarto, and Pritchett (2003) estimate that, in Indonesia alone and at the peak of the increase in poverty following the 1997 crisis, approximately 35 million persons were pushed into absolute poverty.

22. See, in particular, Goldin, Rogers, and Stern (2002). The overall debate on aid effectiveness is reviewed in Clemens, Radelet, and Bhavani (2004).

23. These countries are Denmark, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. See www.oecd.org/dac/stats.

24. See World Bank (2002c).

25. In the parlance of trade policy, this is known as “Mode 4” service trade.

26. See Winters and others (2003).

27. See Maskus (2000). As defined by the World Trade Organization, intellectual property includes copyrights, trademarks, geographical indications, industrial designs, patents, and layout designs of integrated circuits.

28. The terms “acquiring,” “absorbing,” and “communicating” knowledge are from World Bank (1999).

29. This is the main argument of Landes (1998). Landes’ work, however, has come under some criticism for overemphasizing the role of European ideas at the expense of ideas from other part of the world.

30. Goldin, Rogers, and Stern (2002, p. 42). See also chapter 5, this volume.

31. See Kaul, Grunberg, and Stern (1999).