5

Aid

Introduction

This chapter examines foreign aid flows, historically the most recent of the global flows we consider in this book.1 Although ideas, goods, investments, and people have crossed great distances for millennia in response to a host of economic opportunities, it is only relatively recently that governments began to provide financial and technical assistance to foreign countries. The purpose of this assistance has varied and has included geopolitical purposes as well as stimulating economic development, ameliorating poverty and suffering, promoting political outcomes, and ensuring civil stability and equitable governance. Although foreign aid is often visualized by citizens in rich countries in terms of financial “handouts” by rich countries to the world’s poorest inhabitants, the truth is much more complex. Indeed, contrary to popular perception, low-income countries generally receive less than half of total aid. Much of the remainder is made up by flows to middle-income countries such as Colombia and the Arab Republic of Egypt, and some countries of particular interest—Israel, and most recently, Afghanistan—have received significant amounts of assistance.2 The good news is that recent years have seen sharp improvements in both the quality and quantity of aid.

Aid, or official development assistance (ODA) as it is technically known, covers a wide range of both financial and nonfinancial components.3 Cash transfers to developing countries can be vital, but currently they account for less than half of the aid that goes to those countries. Nonfinancial forms of assistance include grants of machinery or equipment as well as less tangible contributions such as providing technical analysis, advice, and capacity-building. Many donors also count their own administrative costs in their aid budgets as well as contributions to debt reduction and other financial allocations that never reach developing countries.4 Just as there is considerable heterogeneity in the types of aid disbursed, there is also a surprising amount of diversity in the countries that receive ODA. For some countries—such as those in early post-conflict situations or where institutions are particularly weak and corruption is prevalent—technical assistance may have a more positive impact than cash transfers, but in the majority of countries, cash transfers in support of government programs are most effective in contributing to growth and reducing poverty.

An analysis of aid flows cannot be separated from an analysis of the development of the international development finance system and the role of institutions such as the World Bank as conduits for financial and other flows. This chapter therefore focuses on both bilateral and multilateral flows as well as on related issues such as the role of official debt and its cancellation.

A Brief History of Aid Flows

In many ways, the histories of modern aid and colonialism are intertwined. In so far as colonialism was an exercise driven by a desire to stimulate and then exploit economic activity abroad, providing investment capital, technology, and technical assistance to colonies was integral to the process. This included constructing a railroad network in the Congo by Belgium to facilitate the extraction of ore deposits, establishing foreign legions of civil service employees, and constructing the Suez and Panama Canals.

Colonial Nature of Early Foreign Aid

It was not until the early 20th century, however, that colonial powers considered providing assistance to support general aspects of economic development that were not exclusively tied to extraction and exploitation. Even here, as noted by Little and Clifford (1965), in the case of the United Kingdom’s 1929 Colonial Development Act, infrastructure rather than, say, education, played a central role. As stressed by Kanbur (forthcoming), it was not until the 1940 and 1945 Colonial Development and Welfare Acts that the United Kingdom began to support education in its nascent foreign aid efforts, although its 1948 Overseas Development Act established the Colonial Development Corporation.

Even after countries gained independence, the colonial nature of foreign aid persisted. Szirmai (2005, chapter 14) stresses the role of aid in decolonization processes, as well as in post-independence assimilation policies, particularly in the cases of the United Kingdom and France. The Netherlands was not exempt in this process either. As Szirmai states, in an example not atypical of the early years of other aid programs,

In the case of the Netherlands, there was a sudden rift with Indonesia in 1949 after the so-called police actions of 1947–49. The Netherlands attempted to restore its damaged international prestige by participating on a large scale in multilateral technical assistance which was beginning at that time. The Netherlands had a reservoir of experience in the form of colonial training programmes, unemployed colonial civil servants and technical experts. It was quite successful in finding employment for its experts in multilateral aid programmes. (p. 586)

Keyterms and Concepts

adjustment programs

aid flows

Cold War

debt overhang

debt-service-to-export ratios

official development assistance (ODA)

capacity building

Green Revolution

technical assistance

tied assistance

Washington Consensus

Tied Nature of Early Foreign Aid

A key feature of these early forms of development assistance was its “tied” nature, in which aid was restricted to importing from the donor country.5 This was true of the Colonial Development Act in the United Kingdom and the “Good Neighbor Policy” of the United States toward Latin America. The practice of tied assistance dominated bilateral aid flows during much of the Cold War and, although there has been considerable progress in untying aid, it remains a feature of a number of aid programs today. To the extent that aid is tied, receiving countries have struggled to extract the full potential benefit, as the assistance provided does not necessarily fit with local choices and priorities. At times, ostensibly magnanimous donations of assistance have in fact had a discernibly detrimental impact on local producers, to the advantage of exporters in the donating country. Concerns are often raised about the efficacy of foreign food aid, for instance, which may ultimately serve to undermine the markets of domestic growers while at the same time providing a captive source of demand for producers in the donor country.6

Modern Foreign Aid in the Wake of World War II

The advent of modern foreign aid may be traced back to the Marshall Plan for bilateral assistance between the United States and Europe in the wake of World War II, as well as to the Bretton Woods Conference and the creation of durable multilateral institutions to facilitate increased international assistance and cooperation, such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (see box 1.2 in chapter 1).7 These efforts were informed by the adverse experiences of past conflicts, whereby the vanquished often had been compelled to pay reparations to the victors. As had been the case with Germany after World War I, such reparations often exacerbated and prolonged the impact of the conflict, leading to financial crises and a lasting sense of resentment. The succession of European wars and failed armistices that resulted had, by 1945, provided a compelling lesson in the need to invest in peace and economic integration. Thus, it was in the shadow of World War II that the international aid architecture was first articulated. Together with much smaller but increasingly significant assistance from private foundations, the combination of bilateral assistance and multilateral institutions has remained the dominant paradigm of international aid flows to the present day. The amount of aid provided and the evolution of aid programs are traced in table 5.1 and figure 5.1.8

Table 5.1 Average Annual Aid Flows per Person in Real 2000 US Dollars, 1960-2003

| Categories of recipients |

1960-9

|

1970-9

|

1980-9

|

1990-9

|

2000-3

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-income countries | $14.72 | $16.85 | $16.23 | $13.82 | $11.41 |

| Middle-income countries | $6.86 | $9.43 | $8.52 | $10.78 | $8.34 |

| High-income countries | $3.38 | $4.16 | $3.94 | $2.94 | $1.50 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on World Bank 2005b.

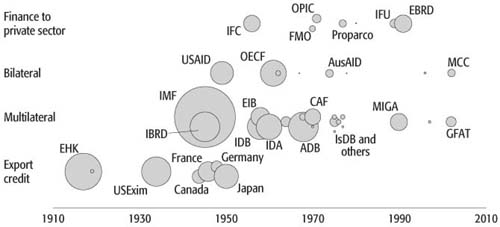

Figure 5.1 Magnitude and Vintage of Major Aid Organizations

Note: Agencies are shown in year of creation, with the area of the circles proportional to their most recent annual aid commitments in US dollars. ADB is Asian Development Bank; AusAID, Austrailian Agency for International Development; CAF, Corporación Andina de Fomento; EHK, Euler Hermes Kreditversicherungs; EIB, European Investment Bank; FMO, Netherlands Development Finance Company; GFAT, Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis, and Malaria; IBRD, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IDA, International Development Association; IDB, Inter-American Development Bank; IFC, International Finance Corporation; IFU, Industrialisation Fund for Developing Countries; IMF, International Monetary Fund; MCC, Millenium Challenge Corporation; MIGA, Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; OECF, Overseas Economic Corporation Fund; OPIC, Overseas Private Investment Corporation; and USEx/Im, Export-Import Bank of the United States. “IsDB and others” includes the Islamic Development Bank, the OPEC Fund, and the Arab Monetary Fund. Some organizations with annual commitments of less than US$1.75 million are not labeled.

Source: World Bank 2004a.

Figure 5.1 and table 5.2 highlight the changing nature of the aid agencies over time, from agencies that focused almost exclusively on promoting exports to a broader multilateral agenda and then, more recently, to underpinning private sector investment. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), established in 1991 after the collapse of the Berlin Wall to support the transition to a market economy in Eastern Europe, is the most modern of the multilateral development banks, and combines lending to both public and private sectors with and without government guarantees.

Table 5.2 Developments in the History of Foreign Aid

| Decade

|

Dominant or rising institutions

|

Donor ideology

|

Donor focus

|

Types of aid

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940s | Marshall Plan, Bretton Woods, and UN system | Planning | Reconstruction | Program assistance |

| 1950s | United States, with USSR | Anti- or pro-Communist building regime capacity | Community development | Food aid and project-based financing |

| 1960s | Bilateral programs | Anti- or pro-Communist building regime capacity | Productive sectors (e.g., Green Revolution), infrastructure | Technical assistance, budgetary support |

| 1970s | Expansion of multilaterals (World Bank and IMF) | Building state capacity, fulfilling basic needs | Poverty and basic needs | Import support |

| 1980s | Nongovernmental organizations | Structural adjustment | Macroeconomic reform | Program-based, debt relief |

| 1990s | Eastern Europe and Ex-USSR as recipients | Structural adjustment then state capacity | Macroeconomic reform and institutions | Human development and sector-focused assistance |

| 2000s | Security and G-8 agenda MDGs | Aid effectiveness, partnership, coherence | Results measurement governance, post conflict | Budget support global programs (e.g., HIV/AIDS) |

Source: Adapted from Hjertholm and White 2000.

Note: MDGs are Millennium Development Goals.

From 1944, upon their incorporation in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, the initial focus of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was on helping to rebuild and reinvigorate war-torn Europe and on ensuring the stability of the world financial system.9 Of the World Bank’s first six loans, five went to countries in Western Europe; the first four were explicitly for post-war reconstruction. The poor countries of the world were not the first priority, and the focus was on raising production and income rather than on broader notions of development. However, with rapid reconstruction progress and the increasing demands of the Cold War, this slowly began to change, and many low- and middle-income countries received increasing flows of international assistance. In 1949, U.S. President Harry Truman set in motion the “Point Four” program for technical assistance in developing countries.10 In 1961, the United States established the Agency for International Development (USAID), and this was followed by similar actions by Sweden in 1962 and Britain in 1964.11 These agencies, along with the African, Asian, and Latin American regional development banks that were established around the same time, complemented the work of the World Bank and provided channels for increased aid flows to the world’s poorest countries. The resulting flows of aid are plotted in figure 5.2. They are given in per capita terms in table 5.1.

Figure 5.2 Inflows of Official Development Assistance by Region, 1960–2004

Source: World Bank 2006a.

For many European countries, the national aid agencies at first mainly concentrated on supporting their former colonies, leaving the broader global challenges of reconstruction and development to global and regional institutions such as the World Bank and the African Development Bank. Increasingly over time, however, there has been a convergence of objectives and strategy, and a global professional cadre of development specialists has been built up. With rapid progress in post-war reconstruction, development assistance began to focus on raising incomes in what came to be called the developing world. At first, the goal was largely confined to raising aggregate national incomes. Then, with the growing recognition that population growth rates vary sharply (so aggregate income did not necessarily give a clear picture of changes in living standards), attention turned to per capita incomes. Soon, with increased understanding of the importance of income distribution, simply raising average per capita incomes also was recognized to be too limited a goal.

By the 1970s, the attention of international aid agencies focused on the twin problems of growth and income distribution and also, increasingly, on the basic needs of poor people.12 Reducing income poverty became a greater priority for the international financial institutions as well as for governments. Some of the major deployments of aid relative to the size of the recipients’ economies are summarized in table 5.3. The table illustrates that, for very small economies, aid can even exceed the size of the national domestic economy. On average, for developing countries, aid contributes around 3 percent of national income, and in Africa the average contribution is around 5 percent. However, as the table shows, some countries—such as Mozambique and Zambia in recent years—have seen aid levels well in excess of half of their domestic economy. Very small economies, with total national incomes of less than US$250 million and populations of fewer than 1 million people, and those emerging from conflict are most prone to very high levels of aid dependence, as table 5.3 illustrates.

Table 5.3 Major Deployments of Foreign Assistance

| Country

|

Year

|

ODA/GDP (percent)

|

Country

|

Year

|

ODA/GDP (percent)

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palau | 1994 | 242 | Micronesia | 2001 | 60 |

| Sao Tome & Principe | 1995 | 185 | Zambia | 1995 | 58 |

| Liberia | 1996 | 108 | Albania | 1992 | 57 |

| Rwanda | 1994 | 95 | Nicaragua | 1991 | 56 |

| Mozambique | 1992 | 79 | The Gambia | 1986 | 55 |

| Kiribati | 1992 | 79 | Tonga | 1979 | 53 |

| Marshall Islands | 2001 | 75 | Cambodia | 1974 | 52 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 1994 | 74 | Cape Verde | 1986 | 51 |

| Timor-Leste | 2000 | 73 | Samoa | 1991 | 51 |

| Somalia | 1980 | 72 | Equatorial Guinea | 1989 | 51 |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on World Bank 2004c.

Foreign Aid and the Cold War

Although the motivation for providing aid in the immediate post-World War II period was driven at the Bretton Woods Conference by reconstruction and broader considerations, this soon was coupled by a growing preoccupation with the politics of the Cold War. From the mid 1950s to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990, aid was increasingly used as a means to support friendly states. Also, originating in the foreign policy of the United States during the early years of the Cold War, economic and military aid were closely interconnected, and aid’s strategic purpose was seen to be at least as much geopolitical as it was humanitarian. It was in this context that Hawkins (1970) in The Principles of Development Aid, suggested that foreign aid belonged to the field of political economy rather than economic analysis. Hayter’s (1971) title, Aid as Imperialism, was even more direct. And Milton Friedman (1958, cited in Kanbur [2003]) from the other end of the ideological spectrum similarly observed, “Foreign economic aid is widely recognized as a weapon in the ideological war in which the United States is now engaged. Its assigned role is to help win over to our side those uncommitted nations that are also underdeveloped and poor” (p. 63).

Foreign Aid after the Cold War: Poverty Reduction Efforts

When aid is disbursed for political or military reasons, with an eye to supporting donor-country exports, or for transition or disaster relief in post-conflict stabilization, any positive effects for poor people generally occur with a long lag time. The end of the Cold War and progress in transition countries have made possible a more direct targeting of aid to poverty reduction efforts. As stated by Goldin, Rogers, and Stern (2002),

Donor financial assistance is targeted far more effectively at poverty reduction than it was a decade ago. At that time, Cold War geopolitics was still exercising a heavy influence on aid allocation, and too many recipient economies were poorly run, often suffering from excessive state intervention in economic activity and poor governance…. As a result, the poverty-reduction effectiveness per dollar of overall ODA has grown rapidly. (pp. 42–43)

Unfortunately, the increase in the effectiveness of aid until 2001 was not accompanied by an increase in its availability. After rising rapidly from 1945 to the early 1960s, flows of aid declined in subsequent decades. Expressed as a percentage of high-income country income (figure 5.2), aid has trended down from slightly over 0.35 percent to approximately 0.2 percent of the GDP of high-income countries in 2001. The good news, however, is that this decline finally appears to have been reversed and the last couple of years have seen a renewed commitment to increasing aid flows. Table 5.4 presents the latest data as well as estimated ODA for 2006.

Table 5.4 ODA as a Share of GNI, 2005 and Estimated for 2006

|

|

Net ODA 2005 (USD millions)

|

ODA as % of GNI 2005

|

ODA as % of GNI estimated 2006

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 1,539 | 0.52 | 0.33 |

| Belgium | 1,924 | 0.53 | 0.50 |

| Denmark | 2,076 | 0.81 | 0.77 |

| Finland | 883 | 0.46 | 0.41 |

| France | 9,893 | 0.47 | 0.47 |

| Germany | 10,013 | 0.36 | 0.33 |

| Greece | 372 | 0.17 | 0.30 |

| Ireland | 703 | 0.42 | 0.50 |

| Italy | 4,958 | 0.29 | 0.33 |

| Luxembourg | 248 | 0.84 | 0.90 |

| Netherlands | 5,036 | 0.82 | 0.82 |

| Portugal | 371 | 0.21 | 0.33 |

| Spain | 2,911 | 0.27 | 0.33 |

| Sweden | 3,377 | 0.94 | 1.00 |

| United Kingdom | 10,640 | 0.47 | 0.42 |

| Eu members, total | 54,943 | 0.44 | 0.43 |

| Australia | 1,557 | 0.25 | 0.28 |

| Canada | 3,410 | 0.34 | 0.28 |

| Japan | 13,534 | 0.28 | 0.20 |

| New Zealand | 251 | 0.27 | 0.27 |

| Norway | 2,494 | 0.94 | 1.00 |

| Switzerland | 1,757 | 0.44 | 0.41 |

| United States | 26,888 | 0.22 | 0.19 |

| DAC Members, Total | 104,835 | 0.33 | 0.30 |

Source: www.oecd.org/statistics OECD-DAC Secretariat 2006.

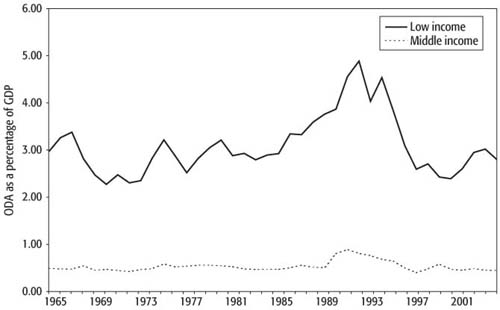

On the recipient side, when expressed as a percentage of the recipient country’s GDP, (or GNI) aid has been relatively constant over the entire period since 1967 (figure 5.3). The average amount of aid received by low-income and middle-income countries over this period was 3.1 and 0.5 percent of GDP, respectively. That said, however, there have been significant declines since the early 1990s, especially for low-income countries. Thus, from the point of view of helping poor people, foreign aid as an aspect of economic globalization can be characterized as a significant, missed opportunity.

Figure 5.3 Foreign Aid Receipts as a Percentage of Low- and Middle-Income Country GDP, 1960–2004

Source: World Bank 2006a.

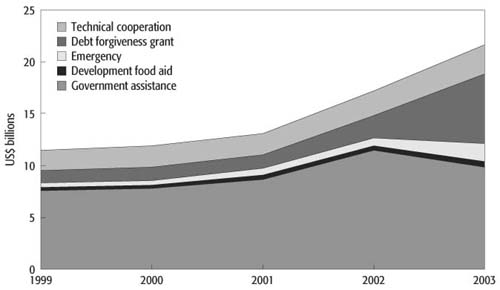

These numbers reflect the upper limit of what countries actually receive, because we know that most bilateral aid does not in fact end up as a cash transfer in the hands of the recipient country. Figure 5.4 illustrates that a great deal of aid is not provided in the form of transfers of financial resources, but rather as food aid, emergency relief, technical cooperation, and debt relief. Although these nondiscretionary forms of aid may make an important contribution, they too often are driven by the priorities of the donors rather than the recipients. They are no substitute for predictable, multiyear flows of aid that are mobilized behind government budgets in national programs that are agreed to across the donor community. Improvements in the quality of aid are necessary as are increases in the volume of aid. For many countries, only a small part—on average around 20 percent—of the aid is provided in the form of direct support to budgeted government programs. This is one of the reasons that the transaction costs of aid are very high and in many cases divert scarce personnel from their ordinary activities of managing public resources.

Figure 5.4 Breakdown of Aid Flows to Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding Nigeria)

Source: OECD Development Assistance Committee and World Bank and authors’ calculations.

Harmonization and coordination is vital to reduce the transaction costs of aid and to ensure that the national priorities of recipient countries are supported, particularly if these are not the same as the pet projects and programs of individual donors and recipient ministries. The transaction costs of aid transfers are also important in determining what portion of total aid flows is spent productively. When ministers have to spend their time hosting visiting dignitaries, and their officials are engaged in satisfying a wide range of donor reporting requirements, the administrative and other burdens imposed by the donors may not only undermine the benefits of the project but also distract officials and scarce skilled staff from more vital priorities. It is for this reason that the recent evolution of donor consultative forums, mobilized behind national strategies and reinforcing existing budget mechanisms and harmonized reporting standards, are so essential. Considerable progress has been made in recent years in harmonizing approaches. A growing number of national and multilateral agencies are reflected in the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, which emphasizes “ownership, harmonization, alignment, results and mutual accountability.”13

One shortcoming of such donor consultative systems, however, is that, because they weaken the direct link between an individual donor and an individual project, they render attributions of individual ODA efforts with country or project outcomes more complex. While harmonization and common platforms almost invariably enhance the effectiveness of ODA, it may be more difficult to demonstrate to skeptical voters in rich countries where their tax payments have gone. For this reason, care may need to be taken in the design of such systems to ensure that donors can still point to concrete examples of where their funding has made a difference.

Modern Goals of Development Assistance

In recent years, the goals of development have come to embrace the elimination of poverty in all its dimensions—income poverty, illiteracy, poor health, insecurity of income, and powerlessness. A consensus is emerging around the view that development means increasing the control that poor people have over their lives—through education, health, and greater participation, as well as through income gains. This view comes not only from the testimony of poor people themselves, but also from advances in conceptual thinking about development.14 It is clear that the various dimensions of poverty are related, and that income growth generally leads to strong progress in the non-income dimensions of poverty as well. It is also clear, however, that direct action taken to reduce poverty in these other dimensions can accelerate the reduction of both income and non-income poverty. Aid policy is beginning to reflect these new understandings.

Levels of development assistance are small compared with both other financial flows and the scale of the challenge at hand. Development aid totaled about US$54 billion in 2000, for example. This was only one-third as much as foreign direct investment (FDI) in developing countries (US$167 billion), which itself was only a small fraction of total investment (nearly US$1.5 trillion). Similarly, although the World Bank is the world’s largest external provider of assistance in the education sector, it typically provides less than US$2 billion in direct assistance for education each year.15 By comparison, annual public spending on education in the developing world totals more than US$250 billion. Given this discrepancy in scale, even if the World Bank were to greatly increase its lending in the sector from around 1 percent to 2 percent, its effectiveness would have to come primarily through catalyzing institutional development and policy change in education rather than through resource transfer alone.

Since, in comparison with domestic investment and government expenditures, aid flows are typically small and should not be viewed as a permanent source of finance, the key challenge is to ensure that they support systemic change, introducing ideas and improving practices that increase the overall size of the resources available for growth and poverty reduction. These indirect effects of aid are difficult to measure, however, and seeking attribution may undermine government leadership and harmonization with other donors. Measuring aid effectiveness is thus necessarily focused on its direct effects. However, because aid flows are relatively small, their direct effects in terms of income increases or reductions in mortality will often be swamped by other factors. For this and the reasons outlined in the next section, evaluating the impact of aid is extremely complex, although vital in order to enhance its effectiveness and create a virtuous cycle of greater willingness to provide aid.

The Multifaceted Impact of Aid

The complexity of social and economic change means that the impact of foreign aid cannot be easily separated from other factors. Countries themselves bear most of the burdens of development, and they rightly claim credit when development succeeds. Assistance works best and can be sustained only when the recipients are strongly committed to development and in charge of the process. In addition, successful projects that draw on foreign assistance in their early stages may later become self-sustaining and serve as sources for lessons that can be applied elsewhere without any foreign involvement at all. For these and other reasons, the positive impact of ODA can be very large. Nevertheless, identifying cause and effect and attributing outcomes to particular actions is often difficult.16 Furthermore, any excessive attempt to claim credit for the successes of foreign aid can devalue the idea and practice of partnership and local leadership. Successful development strategies and actions generally depend on strong country ownership as well as good partnership among donors. This makes it difficult, even counterproductive, for any external actor to claim full credit for a reform or project.

When all aid is lumped together, some analyses have found no clear relationship between aid and growth or poverty reduction.17 But not all aid is aimed directly at poverty reduction, nor has aid always been provided in ways that will maximize growth. Moreover, because aid is often provided to help countries cope with external shocks, even if aid is reasonably well designed and allocated—and thus effective in helping the poor—the positive impact of such aid may be obscured by the magnitude of the shocks.

Kinds of Aid: Disaster Relief and Transition

Disaster relief, for example, is not aimed directly at long-term poverty reduction and, thus, it is no surprise that such aid is not correlated with that result.18 However, it does achieve its goal of helping to avert famine or assisting countries to recover from natural disasters. Similarly, large amounts of aid were directed at supporting the transition in Eastern Europe and Central Asia for both political and economic reasons. There, the mandate in the early 1990s was explicitly to help transform these countries into market economies, rather than to focus directly on reducing poverty.

In addition to these concerns with transition, donors initially placed too much emphasis on the role of what were often isolated projects, neglecting the quality of the overall country environment for growth—a mistake that adjustment (or policy-based) aid was intended to overcome. Finally, as mentioned above, aid was sometimes allocated for pure strategic reasons, with growth and poverty reduction in these cases being distinct secondary concerns, if indeed they were concerns at all. Given this diversity of motives, it is not surprising that aid did not always have the direct effects of spurring growth and reducing poverty.19

Kinds of Aid: Adjustment Programs

The adjustment programs that came into their own in part in response to the severe macroeconomic imbalances of the 1970s, including those that were the result of oil shocks, had their own problems. Donors incorrectly believed that conditionality on loans and grants could substitute for country ownership of reforms. Too often, governments receiving aid were not truly committed to reforms. Moreover, neither donors nor governments focused sufficiently on alleviating poverty in designing adjustment programs.20 In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the pendulum in leading donor countries swung to the new policies of Ronald Reagan in the United States, Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom, and Helmut Kohl in the Federal Republic of Germany. This was reflected in the World Bank by a new emphasis on “getting the prices right” and the articulation of the Washington Consensus, and the aid community focused on macroeconomic reform in developing countries.21 While it was necessary to achieve macroeconomic stability as a prerequisite for sustainable growth and poverty reduction, both donor and recipient countries underestimated the importance of governance, of institutional reforms, and of social investments as a complement to macroeconomic and trade reforms. Prescriptions for reform were too often formulaic, ignoring the central need for country specificity in the design, sequencing, and implementation of reforms.22

As a result, weak governance and institutions reduced the amount of productivity growth and poverty reduction that could result from the macroeconomic reforms. Many of these factors came together in Africa, contributing to the lack of progress in the region. There are many causes to slow development in Africa, including poor domestic policies and institutions and weak commitment to reform, but too often aid did little to improve the situation and in some cases even worsened it. The notable case of Zaire is discussed in box 5.1.

Box 5.1 Aid in Zaire

If there is a worst case of geopolitical aims undermining the effectiveness of foreign aid, it may be Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) under President Mobutu Sese Seko, who ruled from 1965 to 1997. Mobutu was primarily motivated by amassing his own personal fortune, which peaked in the mid-1980s at US$4 billion, even as GNP per capita fell from US$460 in 1975 to US$100 in 1996. Domestic policies were either nonexistent or bad, and private sources of credit consequently disappeared by the mid-1980s. However, with its huge size and strategic location, Zaire was seen as a buffer against the spread of communism in southern and central Africa. Consequently, both bilateral and multilateral aid began to fill the gap as private credit dried up. Between 1960 and 2000, donors disbursed more than US$10 billion in aid to Zaire, with the bulk of this beginning in the 1980s.

Failure to pay adequate attention to corruption and wasteful use of funds severely undermined the effectiveness of this foreign aid. Indeed, total capital flight from the country has been estimated by Ndikumana and Boyce (1998) to be US$12 billion in real 1990 dollars, and Transparency International estimates that US$5 billion was stolen by Mobutu himself. It would be hard to argue much was achieved in Zaire, either in economic or social terms, as a result of the aid.

The result has been increasing skepticism in the donor countries that aid is effective. Well over half of respondents in successive polls believe that aid is wasted, as indeed it often was when it was not aimed at poverty reduction. For aid to lead to poverty reduction, three things are necessary:

- It must aim for poverty reduction rather than geopolitical or other objectives.

- It must go to countries where poor people live.

- It must go to countries whose governments are committed to the eradication of poverty.

Source: Burns, Holman, and Huband 1997; Ndikumana and Boyce 1998; Financial Times, October 13, 2004; and Goldin, Rogers, and Stern 2002; Transparency International 2004.

Rethinking Development Models and the Role of Aid

During the 1990s, a rethinking of development models and the role of aid began. This was facilitated by a combination of four developments.

- First, the end of the Cold War reduced the geopolitical pressures on aid agencies.

- Second, there was an increasing recognition of the successes of India, China, and other developing countries that had achieved macro balance and sustained growth while adopting their own particular development models.23

- Third, mounting evidence suggested an apparent failure of orthodox adjustment models adopted, albeit reluctantly, by African and other highly indebted countries, as seen by the lack of positive growth and poverty outcomes.

- Finally, as discussed in chapter 7, a growing body of analytic literature highlighted the importance of the need for a more comprehensive approach to development and wider understanding of poverty, focusing on human capital (education, health) and physical capital (infrastructure) as well as institutions, governance, and participation.24

As discussed in chapters 1 and 2, the understanding that poverty is about more than income leads to the recognition that growth is not the only determinant of poverty reduction. Social indicators—health and education—improved far faster in all developing countries during the 20th century than would have been expected, given the rate of income growth these countries experienced. Most countries have made major progress in increasing educational attainment and health outcomes by targeting these goals directly and by applying new knowledge and technologies to them specifically, rather than just waiting for the effects of income growth to improve these indicators. At every level of income, infant mortality fell sharply during the 20th century. For example, a typical country with per capita income of $8,000 in 1950 (measured in 1995 US dollars) would have had, on average, an infant mortality rate of 45 per 1,000 live births. By 1970, a country at the same real income level would typically have had an infant mortality rate of only 30 per 1,000, and by 1995, only 15 per 1,000. Similar reductions occurred all along the income spectrum, including in the poorest countries.

The improvements in social indicators have been remarkable by historical standards. Life expectancy in developing countries increased by 20 years over a period of only 40 years, as it increased from the mid-40s to the mid-60s. By comparison, it probably took millennia to improve life expectancy from the mid-20s to the mid-40s. Literacy improvements have also been remarkable: whereas in 1970 nearly two out of every four adults were illiterate, now it is only one out of every four.

These advances in education and health have greatly improved the welfare of individuals and families. Not only are education and health valuable in themselves, but they also increase income-earning capacity. Where macroeconomic analyses of the growth effects of education have been somewhat ambiguous, the microeconomic evidence of the returns to education is overwhelming and robust.25 Research suggests that each additional year of education increases the average individual worker’s wages by at least 5 to 10 percent.26 Educating girls and women is a particularly effective way to raise the human development levels of children. Mothers who are more educated have healthier children, even at a given level of income. They are also more productive in the labor force, which raises household incomes and thereby increases child survival rates—in part because, compared with men, women tend to spend additional income in ways that benefit children more.27

The Importance of Public Policy

These trends make it clear that public policy matters. As we discuss in chapter 7, government has a role not only in ensuring delivery of good basic services in health and education, but also in ensuring that technology and knowledge is spread widely through the economy. The dramatic improvement in life expectancy at a given income level is attributable to environmental changes and is the result of public health actions. The control of diarrhea-related diseases, including the development of oral rehydration therapy to reduce child mortality, is one example; the education of women was an important component of these efforts. Smallpox eradication, made possible through a combination of advances in public health research and effective program management, is another example of a successful 20th century public health effort.28

The statistical evidence shows that large-scale financial aid can generally be used effectively to reduce poverty when reasonably good policies are in place.29 In recent years, donors have increasingly acted on these findings by tailoring support to local needs and circumstances. Thus, the balance of support has moved toward providing large-scale aid to those who can use it well and focusing on knowledge and capacity-building support in other countries. This has been reflected in greater selectivity and coordination in lending on the part of aid agencies, shifting resources toward governance and institutions, emphasizing ownership, and making room for diverse responses to local needs. These new approaches and procedures have begun to pay off. However, it is clear that there is still much to learn: for example, more work is needed on the question of how best to catalyze and support reforms and institution-building in countries with very weak policies, institutions, and governance.

Collier, Deverajan, and Dollar (2001) and Collier and Dollar (2001) sought to quantify the extent to which policies matter for aid effectiveness. Their analysis claims that in 1990, countries with worse policies and institutions received US$44 per capita in ODA from all sources (multilateral and bilateral), while those with better policies received less: only US$39 per capita. By the late 1990s, the situation was reversed: better-policy countries received US$28 per capita, or almost twice as much as the worse-policy countries (US$16 per capita). As a result, the poverty-reduction effectiveness per dollar of overall ODA has grown rapidly. In 1990, a one-time aid increase of US$1 billion allocated across countries in proportion to existing ODA would have permanently lifted an estimated 105,000 people out of poverty; but by 1997–8, that number had improved to 284,000 people lifted out of poverty.30 In other words, the estimated poverty-reduction productivity of ODA nearly tripled during the 1990s. Similar lines of inquiry (for example, Collier and Dollar 2002) suggest that reallocating existing levels of aid more effectively could double the numbers of people lifted out of poverty by these flows.

Why would the overall environment matter so much in determining the effectiveness of ODA? The first reason is very straightforward: policies and institutions affect project quality. For example, a major reason for the dramatic decline in measured World Bank project outcomes in the 1970s and 1980s was the deterioration in policy quality and governance in many borrowing countries. No matter how well designed, a project can easily be undermined by high levels of macroeconomic volatility or of government corruption.

The second reason is more subtle. Even if a project does seem to succeed—based on narrow measures of economic returns and successfully attaining project objectives—the actual marginal contribution of aid funneled through that project may be small or even negative. This is because government resources are often largely fungible: money can be moved relatively easily from one intended use to another. Thus if donors choose to finance a primary education project, displacing local money that would have been used for education, that local money could then be shifted to less productive purposes, such as military spending. In a country with poor public expenditure management, the displaced money could even be diverted to the personal uses of corrupt officials. In this case, the indirect but very real effect of aid could be to promote corruption.31

Should we then use only policy and institutional quality as measures in determining aid flows? Should countries with poor policy and poor institutional quality receive no aid at all? This would probably be too rash a conclusion. Recent research by Clemens, Radelet, and Bhavnani (2004) takes an entirely different approach. Instead of focusing on the different policy and institutional characteristics of recipient countries, they focus on the characteristics of different types of aid flows. Importantly, they consider only what they term “short-impact” aid, which includes budget and balance of payments support, infrastructure investments, and aid for productive sectors such as agriculture and industry. In contrast to previous studies, they find a strong impact of aid on growth (and thus on poverty reduction, at least to some extent) regardless of institutions and policies.32 In light of such evidence, it is necessary to be cautious and avoid a new fadism or herd behavior in the reallocation of aid flows to a small group of countries that meet the criteria. Timely interventions to support reform efforts and to avert famines and other crises remain a vital function of aid.

The above considerations suggest that aid can indeed be very productive. Evidence also suggests that developing countries have never as a group been better able to absorb distributed aid. Additionally, aid agencies have never been better able to disburse aid more effectively. Remarkably, however, as discussed above, although there is virtual unanimity that aid effectiveness has improved, the amount of aid given by rich countries as a share of their income has declined. Since 2001, this trend has reversed, but even optimistic predictions indicate that aid will only account for 0.30 percent of OECD donors’ income in 2006, down from 0.33 percent in 1992 but up from the trough of 0.22 percent.

Improving the Effectiveness of Aid

As we have seen, the development community’s understanding of both development and poverty has evolved in some significant ways. Most importantly, it is now widely accepted that poverty reduction efforts should address poverty in all its dimensions—not only lack of income, but also the lack of health and education, vulnerability to shocks, and poor peoples’ lack of control over their lives.33 This conception of poverty can call for different approaches than those used in the past. Examples of these different approaches include an increased focus on public service delivery to vulnerable groups and greater attention to early disclosure of information that poor people can use.

As we discuss in chapter 7, experience has shown that neither the central planning approach followed by many countries in the 1950s and 1960s nor the minimal-government, free-market approach advocated by many aid agencies in the late 1970s and the 1980s will achieve these development and poverty alleviation goals. Most effective approaches to development will be led by the private sector, but they need to have effective government to provide the governance framework, to assist with or provide physical infrastructure, to invest in education and health, and to ensure the social cohesion necessary for growth and poverty reduction.34 Institutional development has too often been neglected in past policy discussions, but it is now recognized to be essential to sustained poverty reduction. Although a number of key principles for effective development are clear, there is no single road to follow. Countries must devise their own strategies and approaches, appropriate for their own country circumstances and goals.

The most successful development assistance will have effects that reverberate far beyond the confines of the project itself, either because the ideas in the project are replicated elsewhere or because the intervention has helped institutionalize new approaches. As noted above, levels of aid are small relative to the private capital and public resources that it can leverage. Therefore, aid’s largest impact will come through the effects of such demonstration and institution-building. These wider or deeper effects of aid are far harder to measure than its direct effects.

China, India, Mozambique, Poland, Uganda, and Vietnam are all examples of countries where, within the past two decades, policy and institutional reforms have sparked an acceleration of development. In each of these cases, the country and its government have been the prime movers for reform, and each country mapped out its own development strategy and approach. Their experiences do have some common features—most notably an increase in market orientation and macroeconomic stability—and all have seen their growth powered by private sectors (both farms and firms) that have begun to thrive. Although these countries did act along those broad guidelines on development, none of them closely followed any external blueprint for development offered by international institutions and foreign donors.

Yet in all of these cases, development assistance from many sources has supported the transformation. In some cases, advice was more important than lending. In China, for example, aid flows have been dwarfed by inflows of private capital. But development assistance helped pave the way for private sector growth and international integration. For example, external analysis and advice was provided to help China open its economy to investment, unify its exchange rate, and improve its ports early in its transition period.

The converse is also clearly true. There are many examples of countries that have received very large volumes of aid over time, with little result in terms of poverty reduction. A case in point, discussed in box 5.1, is the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire). Also, donor-supported progress on human development indicators in a number of countries has been reversed by the AIDS epidemic or by conflict. In Botswana, which otherwise has a highly successful economy, AIDS reduced life expectancy from 57 years to 39 years in the 1990s. In Sierra Leone, conflict and its aftermath have kept life expectancy at around 35 years. We take up the issues of both HIV/AIDS and conflict in chapter 8 when we present our policy agenda.

Commitment of the leadership is one of the most critical conditions for ensuring the success of reforms, whether they are in the area of the macroeconomy or in combating epidemics such as HIV/AIDS. Evidence has shown that policy change is driven by the country’s own initiative, capacity, and political readiness rather than by foreign assistance and associated loan conditionality.35 Relying heavily on conditionality is ineffective for several reasons:

- It can be difficult to monitor whether a government has in fact fulfilled the conditions, particularly when external shocks muddy the picture.

- Governments may revert to old practices as soon as the money has been disbursed.

- When assessments are subjective, donors may have an incentive to emphasize progress to keep programs moving.

Without country ownership, adjustment lending has not only failed to support reforms, but may have contributed to their delay. For example, case studies of Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Nigeria, and Tanzania all concluded that the availability of aid money in the 1980s postponed much-needed reforms.36

In practice, country commitment has often proved difficult to assess. For example, a government may be seriously committed to a reform program but subsequently find it impossible to implement key measures, sometimes for reasons not fully under the government’s control. In other cases, the government may be interested primarily in the funds, not in the reforms on which the funding is conditional. For this reason, the government’s track record, as measured by the quality of the policies and institutions it has already put in place, is often a good indicator of its commitment to reform. That said, as discussed in the previous section, some types of aid might be effective even with a limited degree of reform. For example, the delivery of aid to eliminate school fees or through providing an incentive to attend school has the potential, already in progress, to educate millions more African children than are educated today.37

Assisting Weak States

If the conclusion of the past 50 years of aid is that aid (and debt relief) should be allocated to countries with a policy and institutional environment that is conducive to effective use, what should be done in countries where this does not exist? Or to put it another way, how can the international community assist countries where states can be characterized as “weak” or “failed?” Approaches that work in the typical low-income country may not be appropriate in post-conflict and weak states, as such states usually lack the governance, institutions, and necessary leadership for reform. In these circumstances, traditional lending conditionality has not worked well to induce and support reform.

Countries with weak or failed states vary widely in their problems and opportunities. As for the better-performing countries, no single strategy will be appropriate for all of them. Each has its specific challenges and must look for unique solutions. Nevertheless, it is useful to distinguish approaches in post-conflict and weak states from those that will work in countries with better policies, institutions, and governance.

Approaches for Post-Conflict and Weak States

Large-scale financial transfers are unlikely to work well in post-conflict and weak states because the absorptive capacity in these environments is quite limited. Instead, donors should focus on knowledge transfer and capacity-building to facilitate change. Because of constraints on government capacity, such efforts should concentrate on a limited reform agenda that is both sensible in economic terms (that is, mindful of sequencing issues—what is possible to achieve and what should be prioritized) and feasible from a sociopolitical standpoint. Only when they develop greater capacity will these countries generally be able to make good use of large-scale aid. There will often be a case for using aid to improve basic health and education services. To be effective, however, funding should probably be directed through channels other than the central government. This suggests wholesale-retail structures in which a donor-monitored wholesaling organization contracts with multiple channels of retail provision, such as the private sector, NGOs, and local governments. The role of the United Nations and its agencies in emergency relief and coordination with donors on refugees for funding and provision of basic services is important and not always sufficiently recognized. The very least that poor people in dire emergencies should be able to expect is that the international community demonstrates that it is able to coordinate and act effectively.

Experience of Sub-Saharan Africa

Improvements in policies and institutions in many Sub-Saharan African countries, combined with examples of successful poverty reduction in a few countries, now provide grounds for hope.38 As policies in many Sub-Saharan African countries improved, so did economic performance: GDP growth rates rose to an average of 4.3 percent in 1994–8, or nearly 2 percentage points higher than it was in the 1980s. A few countries, such as Mozambique and Uganda, have seen especially strong returns to reform. These developments have important implications for aid allocation: although not every country in Africa could absorb an increase in large-scale aid (for reasons described in the previous section), as the effectiveness of aid rises, so too should the amount of aid allocated to the region. Instead, African countries with good policy saw a substantial decline in aid flows in the 1990s, with aid per capita falling by roughly a third, even as prices for export commodities also fell sharply. Annual per capita aid in Africa is currently well below the levels of 20 years ago, while policies are greatly improved, both in the recipient and in the donor countries. For these reasons, much more aid than is currently given to well-performing countries can be effectively utilized.

Aid for Post-Conflict Countries in Need of Reform

Although aid effectiveness requires that large-scale financial assistance be allocated to poor countries that have demonstrated the capacity to use aid well, the international community cannot simply abandon people who live in countries that lack the policies, institutions, and governance necessary for sustained growth and for effective use of aid. Poor people in these countries are among the poorest in the world and face the greatest hurdles in improving their lives. Experience suggests that current technical assistance for capacity-building efforts, as well as the promise of greater financial assistance if policies, institutions, and governance improve, is often insufficient to enable these countries to initiate and sustain reform.

Of the two or three dozen countries with the poorest institutions and policies, only a few have made major improvements in their environments for growth and poverty reduction over the past decade, in contrast to the broad improvements in policies in other developing countries. Ethiopia, Mozambique, and Uganda are unusual among former post-conflict countries in having achieved significant progress. Other post-conflict countries have seen little development progress, and the performance of the development agencies lending portfolio in this group has been relatively poor. Projects have failed there at double the rate for other countries.

Innovative Aid Programs

Despite huge advances in science and in the understanding of the aid and development processes, there is much that we still do not know. Perhaps most important, we do not understand fully how to help improve institutions and governance, especially in the poorest countries where the needs are greatest.39 And we are still learning how best to deal with pressing cross-border issues—such as disease, environmental problems, and political instability—that threaten development.

Global development challenges such as conflict, loss of biodiversity, deforestation, climate change, and the spread of infectious diseases cannot be handled solely by individual countries acting at the national level. They require sustained, multilateral action. As the number and scope of global challenges have grown, so too have the number of actors involved, creating a need for new partnerships and networks among stakeholders. Private charities have become a force in the areas of environment and health. Pharmaceutical companies have become donors to global health initiatives. As discussed in chapter 4, private capital flows to developing countries (especially in the form of FDI) now dwarf official development assistance. The search for international common ground, together with a variety of formal and informal international agreements, have led to new alliances and revised roles for a range of institutions that include the Global Environment Facility, the World Trade Organization, and the various UN bodies. No single actor can speak to all of these challenges, but efforts to address them have been growing rapidly.

According to the UN Secretary General’s office, hundreds of new programs to address issues of global scope are being created each year. Although multinational initiatives are required, they often must be linked to country actions. Many global initiatives address problems that have both important domestic effects and major cross-border spillovers, such as financial contagion, the spread of AIDS, ozone depletion, and toxic pollution. Other global problems call for increasing the efficiency of resources spent at the country level through the use of science and technology available only in the richer countries or globally supported research centers. In most cases, complementary national efforts in developing countries are central to either achieving objectives of the global programs (such as biodiversity conservation, which often builds on local programs) or ensuring developing countries’ access to their benefits (such as agricultural productivity, where new crop varieties must be matched to locally adapted cultivation practices). Here, we take up just three examples of effective global programs, which highlight the benefits of global action on aid.

Onchocerciasis Control Program (OCP)

The first program addresses riverblindness or onchocerciasis, a disease widespread in Africa. It causes blindness, disfigurement, and unbearable itching in its victims, and has rendered large tracts of farmland in Africa uninhabitable. The Onchocerciasis Control Programme (OCP) was created in 1974 with two primary objectives. The first was to eliminate onchocerciasis as a public health problem and as an obstacle to socioeconomic development throughout an 11-country area of West Africa (Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo). The second objective was to leave participating countries with the capacity to maintain this achievement. OCP was sponsored by four agencies: the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Bank, and the World Health Organization (WHO).

OCP has now halted transmission and virtually eliminated prevalence of onchocerciasis throughout the 11-country subregion containing 35 million people. About 600,000 cases of blindness have been prevented, 5 million years of productive labor added to the economies of 11 countries, and 16 million children born within the OCP area have been spared any risk of contracting onchocerciasis. In addition, control operations have freed up an estimated 25 million hectares of arable land that is now experiencing spontaneous settlement. OCP has been hailed as one of the most successful partnerships in the history of development assistance.40 As summarized by Benton and others (2002), “Through a combination of persistence, dedication, and happen-stance, the Onchocerciasis Control Programme evolved from an ambitious plan to a sterling example of disease control” (pp. 8–9).

Given this success, the program has extended operations to what is now called the African Program for Onchocerciasis Control. This program, begun in 1995, extends the OCP to the remaining 19 infested African countries. This effort involves establishing networks of community-directed drug distributors (CDD) that can potentially be used to combat other health problems in the region. Again, as summarized by Benton and others (2002), “What began as a top-down, vertical, disease-control programme has evolved into a bottom-up, integrated approach that couples strong regional co-ordination with the empowerment of local communities to address not only onchocerciasis but, potentially, many other health problems” (p. 12). The potential of the CDD to help combat HIV/AIDS is particularly of interest here.

The Green Revolution

Sometimes building on success involves helping to diffuse ideas across countries and regions through partnership with other development actors.41 The Green Revolution, which began in South Asia in the 1970s and spread to Africa and Latin America, has led to impressive gains in production of basic food crops across the developing world, as shown in table 5.5. Between 1970 and 1997, yields of cereals in developing countries rose more than 75 percent, coarse grains 73 percent, root crops 24 percent, and pulses nearly 11 percent. International aid agencies supported this sweeping change through its lending for irrigation, rural infrastructure, and agriculture, and by mobilizing support with other donors through the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research, better known by its acronym, the CGIAR. This is a second example of an effective aid program.

Table 5.5 Yields of Major Food Crops [kg/ha] in Developing Nations, 1970-2004

| Period

|

Cerealsa |

Coarse grainb |

Root cropsc |

Pulsesd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970-4 | 1,522.1 | 1,112.8 | 9,393.7 | 586.7 |

| 1975-9 | 1,745.4 | 1,308.6 | 10,009.1 | 611.8 |

| 1980-4 | 2,055.5 | 1,500.1 | 10,539.7 | 620.6 |

| 1985-9 | 2,257.1 | 1,561.4 | 10,945.0 | 633.2 |

| 1990-4 | 2,488.7 | 1,756.8 | 11,228.4 | 638.6 |

| 1995-9 | 2,711.0 | 1,955.9 | 11,811.6 | 656.9 |

| 2000-4

|

2,798.6

|

2,040.7

|

12,135.9

|

684.8

|

| Changee | +83.86% | +83.38% | +29.19% | +16.72% |

a. Wheat, rice, other.

b. Corn, barley, rye, oats, millet, sorghum, other.

c. Potatoes, sweet potatoes, cassava, taro, yams.

d. Dry beans, broadbeans, dry peas, chickpeas, cowpeas, pigeon peas, lentils, other.

e. Percentage change from 1970-4 to 2000-4.

Source: FAO Statistic (http://www.fao.org).

The CGIAR, created in 1971, now includes 16 international agricultural research centers. The 8,500 CGIAR scientific staff members work to develop and produce in the following areas:

- higher-yield food crops

- more productive livestock, fish, and trees

- improved farming systems

- better policies

- nenhanced scientific capacity in developing countries.42

The knowledge generated by CGIAR—and the public- and private-sector organizations that work with it as partners, researchers, and advisors—has paid poor consumers handsome dividends in terms of increased output and lower food prices. More than 300 varieties of wheat and rice and more than 200 varieties of maize developed through CGIAR-supported research are being grown by farmers in developing countries. Food production has doubled, improving health and nutrition for millions. New, more environment-friendly technologies developed by CGIAR have released between 230 and 340 million hectares of land for cultivation worldwide, helping to conserve land and water resources and biodiversity. CGIAR’s efforts have helped to reduce pesticide use in developing countries. For example, control of cassava pests alone has increased the value of annual production in Sub-Saharan Africa by US$400 million.

Yet the CGIAR must now meet new challenges. Agriculture research technology has changed, giving prominence to molecular biology and genetic approaches. More robust intellectual property rights have produced an explosion in private investment for agricultural research. These changes pose new challenges to the CGIAR size, organization, and approach as does the urgent need to lift agricultural productivity in Africa. The Commission for Africa (2005) notes that US$340 million a year is required by the CGIAR to help offset Africa’s agricultural productivity deficit.

African Economic Research Consortium (AERC)

A third example of a successful global program is the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC), which is less well known than the first two. Like the river blindness control program, the AERC is a regional program focused on addressing one of Africa’s greatest needs: strong domestic capacity for policy analysis and formulation. Recent development experience shows clearly that development strategies must be “owned” by the countries that implement them, not dictated by outside donors. But the ability to participate in design and decision making that is necessary for ownership depends on local capacity for policy analysis. For this reason, capacity building is an essential element of development assistance.

The international nature of the AERC has made it stronger by supporting a critical mass of researchers and academic institutions, and by encouraging the sharing of experiences across countries. Its mission statement has as its principle objective “to strengthen local capacity for conducting independent, rigorous inquiry into problems pertinent to the management of economies in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Established in 1988, this initiative now covers 22 countries.

Established by six international and bilateral agencies and private foundations, AERC is now funded by 15 donors, including foundations, governments, and multilateral organizations. It has a budget of approximately US$7 million a year. The AERC conducts research in-house and administers a small grants program for researchers in academia and policy-making institutions.43 In addition to its research program, the AERC began in 1992 to administer a two-year collaborative Masters of Arts (MA) program in economics with students and faculty from 20 universities in 15 Sub-Saharan African countries. The program has produced about 800 MA graduates in economics to date, and 200 more students now participate in this program. Many graduates of the AERC have gone on to research and teaching posts throughout the region, and others to high-level positions in African central banks and finance ministries.

Easing the Burden of Debt

As we related in chapter 4, debt financing has been an important part of financing in developing countries for centuries and no reading of economic history is complete without reference to the debt crises of previous eras. The first recent major debt crisis to take place, and in which aid policies included significant debt components, occurred when an oil-price shock and global recession hit in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Commodity prices turned sharply against the non-oil commodity exporters, making it difficult for them to pay for both imports and debt service. While interest rates were rising, official lending increased to help cushion the effects of the shock, and to substitute for finance from commercial sources, which for most borrowing countries evaporated.

Components of Foreign Debt

For all countries, including developing countries, any deficit on the current account (such as through trade deficits) that is not made up for by net factor receipts, transfers such as foreign aid, FDI, or a reduction in foreign reserves necessarily translates into foreign debt as the country sells financial assets of various kinds to generate an offsetting surplus on the capital account.44 It sometimes makes sense for developing countries to engage in short-term borrowing of this kind to cover short-term current account deficits.

Build Up of Unsustainable Debt in Highly Indebted Countries

Increasingly from the 1950s, developing countries had access to more long-term borrowing, which in most instances is better suited to their needs. However, where such borrowing is not used to make productive investments that increase output of the tradable sectors of the economy (which increase exports relative to imports), current accounts will persist indefinitely, and debt will build up to unsustainable levels.

In many of the highly-indebted countries, the expected improvements in policy performance did not materialize, whether because of insufficient commitment by borrowers or because the design of the adjustment had not paid enough attention to the political economy of reform, governance, and corruption or to social concerns. In other cases, reforms were implemented but did not lead to the expected supply and growth response. As a result, the GDP average growth rate between 1980 and 1987 of the 33 countries that were characterized in the mid-1990s as the most severely indebted low-income countries was just 1.9 percent—which translated into an income decline in per capita terms. The cumulative effect of the shock and economic decline was that a debt burden that had been reasonable became unsustainable. Between 1982 and 1992, the debt-to-export ratio of the 33 most highly indebted countries rose from 266 to 620 percent.45

The Debt Crisis

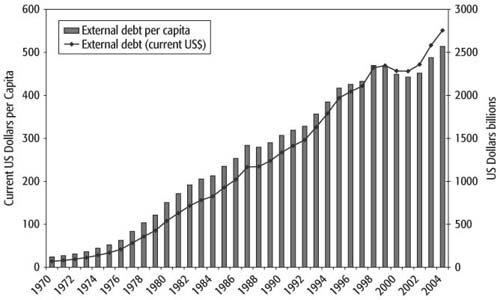

The recent history of external debt is traced in figure 5.5, both in total terms (solid line and right-hand axis) and in per capita terms (vertical bars, left-hand axis). Significant increases in both measures began in the mid-1970s. As reported in Reinert (2005), “Beginning in 1976, the IMF began to sound warnings about the sustainability of developing-country borrowing from the commercial banking system. The banking system reacted with hostility to these warnings, arguing that the Fund had no place interfering with private transactions” (p. 259).

Figure 5.5 External Debt of Developing Countries

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators 2006.

The IMF’s warnings became clear when the “debt crisis” began in 1982. The initiating event was Mexico’s announcement that it would stop servicing its foreign currency debt. Within months, the debt crisis had spread to Brazil and Argentina. In 1982, the total external debt of developing countries was approximately US$750 billion and per capita external debt was approximately US$200. As can be seen in figure 5.5, both total and per capita external debt continued to increase significantly through 1999 to approximately US$2,400 billion and US$514 per capita. Indeed, between 1990 and 2002, the total external debt for developing countries increased by approximately US$1 trillion, the bulk of which was for middle-income countries. These continued debt burdens in the developing world negatively affect both growth prospects and the financing of basic public services. Both of these, in turn, negatively affect poverty in all its dimensions.

International Debt Relief Efforts: HIPC Initiative

Since the late 1980s, the international development community has attempted to address the problem through a variety of debt-reduction mechanisms. In 1996 it went a step further, creating the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) debt relief initiative to deepen debt relief for poor countries suffering from unsustainable debt burdens. The initiative aims to increase the effectiveness of aid by helping poor countries achieve sustainable levels of debt while strengthening the link between debt relief and strong policy performance. Forty-two countries, primarily from the Sub-Saharan Africa region, are identified as potentially eligible to receive debt relief under this initiative. As of October 2004, 27 countries had met the required governance and other standards and are receiving debt relief that will amount to about US$54 billion over time.46Debt-service-to-export ratios have been reduced for this set of countries to an average of 10 percent.47

Not only does HIPC reduce debt overhang, it also supports positive change toward better poverty reduction. Debt relief under the HIPC initiative is intended for countries that are pursuing effective poverty reduction strategies as ascertained by the World Bank and the IMF; both better public expenditure management and increased social expenditures are critical elements of this affirmation of effectiveness (www.worldbank.org/debt). For the countries that have received HIPC relief, the ratio of social expenditures to GDP is projected to increase significantly. The challenges are to ensure that these expenditures translate into better outcomes in the social sector; that vital infrastructure improvements also increase; and, more important, that the broader policy environment continues to improve and support growth and poverty reduction.

The HIPC experience has demonstrated that debt relief can work. It is clear, however, that the amounts allocated within HIPC—the debts that are written off—are insufficient to put all low-income countries on a sustainable debt repayment path and to ease the pressure on their debt servicing sufficiently to allow an accelerated reallocation of funds toward required investments in infrastructure, education, health, and other poverty reduction expenditures. A new framework for debt sustainability was therefore needed to match the need for funds in low-income countries with their ability to service debt. This requires substantial increases in the funds available. The July 2005 commitment at the Gleneagles, Scotland, summit of the Group of Eight leaders to allocate US$40 billion for additional debt relief is a significant step forward. The Group of Eight confirmed that these funds will be “additional” to previous commitments to increase aid (including to the International Development Association) and that finance that would go to the better performers who had paid their debts would not be cannibalized to write off the debts of the eligible HIPC countries.

While the accelerated cancellation of debt has been widely welcomed, there are concerns regarding the moral hazard and incentive effect of debt write-offs. For those countries that have diligently repaid their debts or carefully constrained their debt burden, the prospect of additional aid flows being given to reduce the obligations of those who have been less prudent may seem unfair. To add to this complexity is the question of the intertemporal nature of debt—the debts being repaid today typically were incurred by previous generations of leaders. Many individuals and some current governments in countries where dictators incurred debts argue that these debts are illegitimate. There are moves that do not necessarily have government support in a wide range of countries, including Indonesia, Nigeria, and South Africa to write off what may be termed illegitimate or “odious” debts, and this precedent has been established for Iraq.48

Without debating the virtues of this position, the key issue is the source of these additional funds. Global flows, like national flows, need to be sourced and paid for with additional commitments. In honoring their commitments to increasing aid, the rich countries need to ensure that funding to meet debt forgiveness is additional and does not represent a claim on existing or future commitments to other forms of aid. They also need to ensure that all countries that are able to use aid effectively benefit from additional flows, so that easing the burden of debt does not come at the expense of poor people in other countries.

The Millennium Development Goals and Donor Coordination

A key driver of the effectiveness of aid flows is that they become more predictable and that there is harmonization behind country-owned programs. Too many ministers and civil servants in poor countries spend their time servicing the needs of donors—from taking visiting dignitaries to visit their pet projects to meeting the unique audit and reporting needs of the different aid and donor agencies. In Tanzania, for example, it was estimated that well over a thousand quarterly reports need to be completed for donors. Aid agencies have a responsibility to ensure that their requirements are harmonized in a set of common standards and that their demands on countries are focused on ensuring that the money goes to projects and programs prioritized in national budgets, rather than to individual projects in localities favored by foreign or domestic politicians. In addition, donors have a responsibility to ensure that their flows are predictable, that they agree to multiyear commitments, and that they are not restricted to contracts or goods and services procured from the donor country. A visit to virtually any low-income country reveals the carcasses of projects and programs initiated through donor pressure and promises and that have failed through lack of follow-through in funding and maintenance.

The commitment in 2002 by heads of state of both rich and poor countries to achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) requires the following, as set out in more detail in box 5.2:

- halving poverty and hunger by 2015

- achieving universal primary education

- eliminating gender disparity in education

- reducing by three-quarters maternal mortality

- combating HIV/AIDS and other diseases

- halving the proportion of people without access to potable water

- a global partnership for development.

This agreement reflected a unique coming together in terms of defining the problem and the role of different actors. It has given clear common goals to the international community, and not least to donor agencies and the multilateral institutions, as well as a set of agreed measurable targets and results.

Box 5.2 Millennium Development Goals