3

Trade

Introduction

International trade is potentially a powerful force for poverty reduction. Trade can contribute to poverty alleviation by expanding markets, creating jobs, promoting competition, raising productivity, and providing new ideas and technologies, each of which has the potential for increasing the real incomes of poor people. We emphasize the word “potential” because the link between trade and poverty alleviation is not automatic.1 Indeed, as the recent histories of a number of countries demonstrate, it would be a mistake to rely on trade liberalization alone to reduce poverty. A more comprehensive approach is needed—one that addresses multiple economic and social challenges simultaneously and that emphasizes the expansion of poor people’s capabilities, especially in the areas of health and education.2 Such an approach also needs to address the business climate, infrastructure, and other barriers that prevent potential importers and exporters from benefiting from the opportunities afforded by more open markets. Trade has a vital role to play, and we explore this in the present chapter.

As we emphasize below, improving market access for developing countries is a priority. This would yield benefits that far exceed those of additional aid or debt relief. Additional aid to enhance trade is, however, a vital complement to ensure that low-income countries take advantage of increased access to markets.

International Trade and Its Impact on Poverty

As has been long recognized by international economists, international trade is a means of expanding markets, and market expansion can generate employment and incomes for poor people. In many discussions of globalization, comparisons have been made between the wages of workers in poor-country export industries and the wages of workers in developed countries. In these comparisons, the wages of workers in developing countries’ export industries often appear to be very low. Consequently, globalization has often been identified as worsening poverty. However, comparison between what people may have earned before and after trade opportunities became available is perhaps more relevant. From a poverty perspective, this comparison could be between the wages of export sector workers and agricultural day laborers, both in the same developing country. Often the alternative of work as an agricultural day laborer is much worse than the work of an export sector worker. It is precisely this type of income comparison that draws workers into export industries.3

Export Activity

It must also be kept in mind that not all export activity is equal from the point of view of raising the incomes of poor people. The export sector can best help to alleviate poverty when it supports labor-intensive production, human capital accumulation (both education and health), or technological learning. These characteristics were often present in the successful East Asian export expansion of recent decades. Their weakness in other countries’ export expansions helps to explain why export expansions have not always done as much as could be done to help poor people. In addition, the incomes of poor individuals depend on buoyant and sustainable export incomes, which in turn depend on export prices. Export activity with declining export prices, a characteristic of many primary commodities, does not lend itself to sustain poverty alleviation.

Competition

International trade is also a means of promoting competition, and in many instances, this can help poor people. Increased competition lowers the real costs of both consumption and production. For example, domestic monopolies charge monopoly prices that can be significantly higher than competitive prices. The competition introduced by imports erodes the market power of firms that at times dominate markets and undermine consumer choice. These “procompetitive effects” of trade can make tight household budgets go farther and lower costs of production, for example, through lowering the costs of fertilizer or fuel. Consumers also suffer when they have to pay artificially high prices for food or clothing products. It is estimated that in the European Union, Japan, and the United States, consumers pay over US$1,000 more for their food than would be the case if trade barriers were reduced. This harms poor people in rich and poor countries alike. Lower production costs can have knock-on employment effects advantageous to poor individuals by lowering nonwage costs in labor-intensive production activities. Procompetitive effects can also arise in the case of monopsony (single-buyer) power.4 In this case, sellers (small farmers, for example) to the previously monopsonistic buyer are able to obtain higher prices for their goods as the buying power of the single-buyer is eroded.

Key Terms and Concepts

Export Processing Zones (EPZs)

high-technology manufactured exports (HTME)

maquiladora export sector

market expansion

monopsony

multinational enterprises (MNEs)

openness ratio

primary commodities

real (price adjusted) wages

tariffs

tariff escalation

tariff protection

trade liberalization

value chains

Productivity Increases: Exports

For export activities to support poverty alleviation in a sustained manner, it helps if those activities lend themselves to technological upgrading and associated learning processes. There is some evidence that international trade can promote productivity in a country, and it is possible that productivity increases can in turn support the incomes of poor people. Neither of these processes is automatic, however. It is not the case that exports of all types or in all countries generate positive productivity effects, but there is evidence that this is the case in certain instances. The export process can place the exporting firms in direct contact with discerning international customers, thus facilitating upgrading processes. There is no consensus among international economists on the extent of these upgrading effects, but they nonetheless remain an important possibility that has been active in sectors such as the Indian software industry.5

Productivity Increases: Imports

Productivity increases can occur because of imports as well as exports. In this case, the process is typically related to the imports of new machinery that embody more advanced technologies than the machinery they replace in the importing country. Again the issue arises as to the extent to which this upgrading supports the incomes of poor people. For example, as Chile and Costa Rica liberalized their trading regimes, firms imported more physical capital (machines) to remain competitive. Embodied in these machines was a newer technology level that demanded relatively more skilled workers than the old technology that had been in use. Consequently, as trade was liberalized, the unskilled workers lost in terms of relative wages, while workers who were more highly skilled gained. Because poor people are almost always unskilled, these particular changes worked against them.6 As discussed by de Ferranti and others (2002) in the context of Latin America, this is one of a number of reasons why upgrading skills is crucial for trade (and for foreign direct investment [FDI], discussed in chapter 4) to have a positive impact on poverty.

Access to Foreign Markets

For positive effects of trade to occur, developing countries need access to foreign markets. Unfortunately, as has been very well documented by both trade economists and development organizations, the high-income countries of the world maintain their greatest protective measures in exactly the same markets that are most important for the developing world: agriculture, food processing, and labor-intensive manufactures. In addition, there is substantial evidence of what trade economists call tariff escalation, where high-income countries increase the level of protection along with the degree of processing of a product, resisting diversification up and down value chains that are so important to development processes.7 In many cases, lack of market access hurts poor individuals both directly by reducing employment opportunities and indirectly by contributing to declining export prices, particularly for primary commodities.8

Impact on Health and Safety

International trade can have direct health and safety effects on poor individuals, which can be beneficial or detrimental. Perhaps most important, improving the health outcomes of poor people usually involves imports of medicines and medical products. It is simply not possible for small developing countries to produce the entire range of even some of the more basic medical supplies, much less more advanced medical equipment and pharmaceuticals. It is also the case that many developing counties import (legally or illegally) large amounts of weaponry and export sexual services, both of which can have dramatically negative outcomes for the health and safety of poor individuals.9 In addition, the production processes of some export industries can adversely affect the health of workers in those industries, and a small but important amount of trade involves hazardous waste dumping. We will address both the positive and the negative impacts of trade on health and safety in this chapter.

Characteristics of Developing-Country Trade

Before we begin our analysis of the relationship between trade and poverty alleviation, let’s recall a few relevant characteristics of developing-country trade from chapter 2.

- First, total trade flows (for example, total exports) of developing countries are substantially larger than inflows of FDI, portfolio investment, and foreign aid receipts. Even the largest of these (FDI) is only approximately one-fifth the size of exports. Trade is therefore of utmost importance for developing countries as a whole.

- Second, for low-income countries (but not for middle-income countries), we need to modify the first statement somewhat. For these countries, aid sometimes reaches the value of a third of their exports. Relative to exports, aid is more important than FDI for these poorer countries.

- Third, manufactured exports are increasingly important for developing countries, both low- and middle income, although agricultural exports are more important for low-income countries than for middle-income ones.

- Fourth, commercial service exports are important for all developing countries, especially when compared with agricultural exports.

These are a few important characteristics of trade that we will keep in mind as we investigate its role in global poverty alleviation. We begin with the market expansion effects of trade.

Market Expansion

The development NGO Oxfam (2002a) has rightly noted that “History makes a mockery of the claim that trade cannot work for the poor” and that “Export success can play a key role in poverty reduction” (p. 8). Some in the anti-globalization movement would deny such claims, while many pro-globalist observers would claim that these processes are automatic. Here we take an intermediate view, observing that export expansion has the potential for increasing the real incomes of poor people.

Role of Trade in Alleviating Poverty

In discussions of the more high-tech aspects of globalization, it is often forgotten that 70 percent of the world’s “dollar poor” (those consuming below US$1 per day at 1985 purchasing power parity levels) reside in rural areas.10 For this reason, poverty alleviation cannot ignore rural development, and the potential role that trade can play in poverty alleviation depends in large measure on the possibility of supporting rural incomes, either through farm or nonfarm activities. One such example can be found in Vietnam’s rice sector.

Supporting Rural Incomes: Vietnam’s Rice Sector

In the case of Vietnam, this support of rural areas has occurred, at least to some degree. As a result of a package of reforms in the late 1980s that included gradual trade liberalization, Vietnam turned from a rice importer to a rice exporter despite the role of this crop as the country’s main staple food. Vietnam is now one of the largest rice exporters in the world.

This trade-based market expansion in Vietnam supported household incomes because of the widespread participation of small farms in Vietnam’s rice sector. Indeed, rice is grown by two-thirds of Vietnam’s households. Rice exports increased the incomes of these small farms and, because rice production is labor intensive in Vietnam, increased demand for rural labor.11 Thus, Vietnam’s rice exports have indeed supported rural incomes, helped to alleviate poverty, and even improved nutrition and reduced child labor.12 The key here is the involvement of labor-intensive, smallholder farmers; such success has been noted in other countries such as Uganda, where smallholder agriculture has been supported by export market expansion. Where export expansion supports large-scale, capital-intensive agriculture, and where land ownership is highly concentrated, these poverty alleviation effects are weaker. Finally, it is important to note that Vietnam’s trade liberalization has not been orthodox. For example, it has employed an export quota (maximum exports) to ensure that domestic rice prices do not rise too much to the detriment of consumption. This has been important for the rural poor for whom the bulk of caloric intake is from rice.

Supporting Manufacturing Incomes: Bangladesh’s Clothing Industry

Although rural incomes are most often central to large-scale poverty alleviation, supporting goals of poverty alleviation is not confined to agriculture. Indeed, labor-intensive manufacturing has been an important part of poverty-alleviating trade expansions in much of the developing world. This was the case in the famed export expansion of East Asian countries, and it has also been seen in more recent cases such as Bangladesh’s clothing exports. In Bangladesh’s case, poverty reduction during the 1990s was quite dramatic and, although changes in the nontradable sector were a significant factor in this reduction, clothing exports also played an important role. Nearly 2 million Bangladeshis work in the clothing sector’s nearly 3,000 factories. Oxfam’s (2002a) description of this sector illustrates the point that wage comparisons must be relevant to the workers themselves to be truly useful:

Most of the (clothing) workforce consists of young women, many of whom have migrated from desperately poor rural areas. The wages earned by these women are exceptionally low by international standards, and barely above the national poverty line. Yet their daily wage rates are around twice as high as those paid for agricultural labourers, and higher than could be earned on construction sites. Employment conditions in the export zones are scandalously poor, with women denied even the most basic rights. Yet for most women working in the garments sector, their employment offers a higher quality of life than might otherwise be possible. (p. 56)

Although it is true that the wages in the Bangladesh garment sector are barely US$2 per day, this labor-intensive employment has provided an opportunity to leave worse conditions in rural and urban poverty. To be blunt, it has been a difference between poverty and extreme poverty. Indeed, using survey data from 1990 and 1997, Zohir (2001), Kabeer (2004), and Kabeer and Mahmud (2004) provide evidence that work in the garment sector has had a number of beneficial effects on women workers in Bangladesh. These include first-time access to cash income, support of families in rural areas through remittances, support of siblings’ education, and increased household status. Zohir’s conclusion is that “employment in the garment industry has definitely empowered women, increased their mobility and expanded their individual choice” (p. 67).13 Similar evidence in five additional countries of the way exports can support women’s incomes is provided by Nordas (2003), who concludes that export industries in Mauritius, Mexico, Peru, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka are more likely to employ women than men and that they also tend to increase women’s wages relative to men’s.

Promise of Technological Upgrading

While labor-intensive manufacturing offers an important way to support the incomes of poor people, its long-run promise lies in the potential for technological upgrading. Without technological upgrading, it is likely that the economy will not contribute to long-term poverty alleviation. We will consider this process in the section on productivity. First, however, we consider the issue of competition.

Competition

International economists have begun to understand the ways that international trade can promote competition in developing countries. In many instances, increased competition can help poor people by lowering the real costs of household consumption and production. As mentioned earlier, a domestic firm with market power can raise prices above competitive levels, and import competition can erode this market power.

What trade economists call the “procompetitive effects” of trade does have the potential to help the poor in some instances.14 Procompetitive effects can also occur in the case of monopsony (single-buyer) power. Here, sellers (small farmers, for example) to the monopsony buyer are able to obtain higher prices for their goods as the buying power of the monopsonist is eroded. We give examples of each of these possibilities here.

Procompetitive Effects: Grameen Bank’s Village Phone Program in Bangladesh

The Grameen Bank’s Village Phone Program demonstrates how imported technologies, when introduced in the context of a well-thought-out and targeted policy framework, can make a dramatic difference in the lives of the poorest of the poor. Before this program, Bangladesh had one of the lowest telephone penetration rates in the world: only 1.5 percent of households had access to a telephone. Although the lack of a functioning telecommunications service posed serious frustrations for all Bangladeshis, it was particularly costly for the country’s farmers and local producers. For these individuals, the lack of telecommunication service imposed serious costs by denying them critical access to the price information necessary to make efficient production decisions and to negotiate with middlemen and marketers on a fair basis.

In 1997, the Grameen Bank, Bangladesh’s renowned village-based microcredit organization, launched the Village Phone Program. The program provided selected female members of Grameen Bank’s peer-based microcredit networks with loans of taka 12,000 (US$200) to purchase an imported cellular handset and mobile service subscription. The women were then trained on the use and marketing of mobile phone technology, enabling them to earn money while helping their fellow villagers gain access to information at a fraction of what it had previously cost them.15

As of late 2003, Grameen Phone estimated that the Village Phone Program was providing 50 million people living in remote rural areas with access to telecommunications facilities. Critically, the advent of village phones has dramatically improved the profitability of small farmers. Farmers in villages with village phone programs, for instance, receive 70 to 75 percent of the retail price, compared with 65 to 70 percent received by farmers in villages without phones.16 Participants also reported that village phones have significantly helped facilitate the regular delivery of inputs at low cost, reduced the risk of new diseases infecting poultry or livestock, and have offered immeasurable assistance in averting the adverse effects of natural calamities and crime.17 Thus, the combination of imported technology with an antipoverty policy framework has improved competition in a manner that has been quite beneficial for poor individuals. By vesting control of this new technology in the hands of poor female villagers, the Grameen Bank program represented a dramatic change in economic tradition for Bangladesh, where local elites had ordinarily introduced new innovations and reaped large profits as a consequence.

Procompetitive Effects: Cotton Farmers in Zimbabwe

Examples of procompetitive effects that support the poor can be found in other areas. For instance, there is some evidence that trade liberalization in Zimbabwe during the early 1990s eroded the monopsony buying power of the national cotton marketing board and thereby supported the entry, output, and incomes of smaller cotton producers.18 Following trade liberalization, additional cotton buyers emerged, including one owned by the cotton farmers themselves. This particular buyer became involved in providing extension services to smallholder cotton farmers that previously were not available. Also during this period in Zimbabwe, there was entry of over 3,000 new, small-scale hammer mills in the maize processing sector, employing thousands of new workers and leading to an increase in the consumption of hammer-milled maize meal.19

Assessing Effects of Procompetitive Trade

Examples such as these indicate that, under certain circumstances at least, poor people can take advantage of increased competition that can result from international trade. Assessing such effects is an emerging area of inquiry. Nevertheless, we are convinced that such effects matter for poor people. It also must be recognized, however, that there are circumstances where certain kinds of liberalization that accompany trade liberalization episodes can actually be anticompetitive (for example, some kinds of privatization where new monopolies are created) and hurt the poor. It is necessary to keep an eye on competitiveness issues to fully assess the impact of trade on poverty.

Productivity

There is an insight from the field of the microeconomics of labor markets that has important implications for poverty alleviation. This insight is that long-term increases in real (price adjusted) wages require long-term increases in productivity. As noted by UNCTAD (2004), “sustained poverty reduction occurs through the efficient development and utilization of productive capacities in a manner in which the working age population becomes more and more fully and productively employed” (p. 90, emphasis added). There is some evidence that international trade can promote productivity in a country, and that productivity increases can in turn support the incomes of poor people. The link between trade and productivity improvements is a potential one and is not automatic. It can be related to both imports and exports.20

Trade and Productivity: Import Side

On the import side, trade allows countries to import ideas and capital goods (such as machinery) embodying the new technologies that make productivity increases possible. New technologies, however, require a learning process both to master them and to adapt them to local conditions. As described by Rodrigo (2001), “Learning takes place when unit variable cost in production declines with cumulative output as workers, supervisors and managers build up skills around a specific production process” (p. 88). Without learning, technological improvements are usually impossible.

Trade and Productivity: Export Side

On the export side, foreign market access supports the learning process. Again, as described by Rodrigo (2001), “By opening up a channel to the world market, trade … serves to promote specialization and sustain production tempos of goods in which learning effects are embodied; if constrained by domestic market size alone along with associated domestic business cycle uncertainty of demand, firms would be less willing to make the investments needed to capture gains from learning” (p. 90). Thus, openness to trade, both import and export, can support technological upgrading via learning.21 For this process to occur, trade needs to support human capital accumulation upon which learning depends.22 It also, as Friedman (2005) vividly highlights, requires openness to ideas, which we discuss in chapter 7.

Trade and Productivity: Importance of Learning

Productivity increases can occur in agriculture, manufacturing, and services. They are not, as often supposed, limited to manufacturing alone.23 As discussed in chapter 2, trade in agriculture, manufacturing, and services are all important for the low- and middle-income countries of the world, and trade-induced learning processes can operate across all three of these sectors in the developing world. That said, evidence on learning and technological upgrading is more readily available for the manufacturing sector, so it is worth considering this sector as an example of the way that trade-induced learning can support real incomes over the long term.

In the realm of manufacturing, the importance of learning is reflected in the observation of Lall and Teubal (1998) that, for developing countries, mastering existing technologies is more important than innovating new technologies. The learning process in manufacturing is characterized by these authors as “constant, intensive and purposive” and requires the external support of education and training that is technology specific. This indicates that complementary education policies of the public sector are important for trade-supported productivity gains. Trade alone is not sufficient. One example of this is the initiative of the Costa Rican government to supply schools with computer technologies in support of a hoped-for emergence of an export-oriented computer products sector. This effort proved to be successful.

Empirical Evidence of Successful Learning

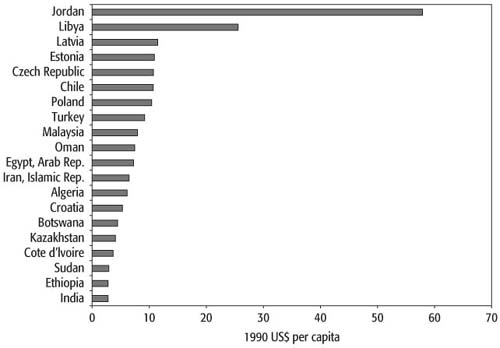

The empirical evidence on the manufacturing sector suggests that successful learning is not as widespread as one would hope.24 Note the evidence presented in figure 3.1. This figure considers the sophistication of manufactured exports for a set of low- and middle-income countries for the year 2003. These 15 countries account for 97 percent of reported high-technology manufactured exports (HTME) from the low- and middle-income countries. High-technology manufacturing exports are highly concentrated in the developing world. Even within the 15 countries reported in this figure, the bulk of high-technology exports are concentrated at the top of the list: in China, Malaysia, Mexico, the Philippines, and Thailand. As emphasized by Lall (1998),

The nature of learning varies greatly by country, depending on initial capabilities, the efficacy of markets and institutions, and the policies undertaken to improve them. Some countries lack the skill and technical base to engage in modern manufactured exports, except for the simplest ones (low quality garments or toys) where foreign investors bring in the technology and provide the (minimal) training needed; some can tackle the manufacture of complex products (automobiles); and some can manage the design and development of new technologies in advanced products. Their capability differences determine the nature and dynamism of comparative advantage. (p. 66)

Figure 3.1 Low- and High-Technology Manufactured Exports of Some Developing Countries, 2003 (millions of US dollars)

Note: LTME is low-technology manufactured exports; HTME is high-technology manufactured exports.

Source: World Bank 2006a.

Learning and Skill Levels

Indeed, one can distinguish (as Lall [1998] does) between the basic learning that is required to export low-technology manufactured exports and the deep learning that is required to export high-technology manufactured exports. The required complementary education and training policies differ in these two instances. As Lall points out, “In early stages of industrialization, when skill needs are fairly low and general, the correct policy is functional support for schooling and basic vocational training. In later stages, with more complex activities and functions, skill needs grow more demanding, diverse, and specific to particular technologies” (p. 68). Beginning the process of basic learning, supported by functional educational advances, and then transitioning into deep learning, supported by more specific educational advances, are both important but not easy to achieve, especially when educational resources are scarce. But it is essential, as the long-run support of real incomes depends on countries’ abilities to do this.25

Learning for High-Technology Manufacture Exports: The Maquiladora Export Sector

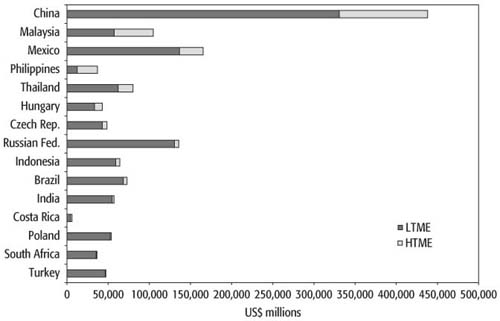

The deep learning process that supports high-technology manufacture exports is important because there is some evidence that low-technology manufacturing exports can fail to deliver long-term real wage increases. It is becoming clear that not all manufacturing activity supports productivity increases from technological learning over the long term. The country in figure 3.1 with the third-highest level of high-technology manufacturing exports is Mexico. However, as can be seen in that figure, the bulk of its manufacturing exports are low-technology in nature. In the case of assembly or maquiladora export sector of Mexico, there are limits to productivity increases despite the generation of over 1 million jobs. For example, figure 3.2 plots imported inputs, value added, and wages as a percentage of gross production value for a quarter of a century in Mexico. As can be seen in this figure, imported intermediate products as a percentage of production value has been on a steady rise, while value added and wages as a percent of production value have been on a steady decline. Why does this matter? There is a great deal of evidence that long-term productivity in exporting activities in support of long-term increases in real wages relies on manufacturing export activities being integrated into the local economy via sourcing of local inputs and local value added. Just the opposite appears to have occurred in the Mexican maquila sector.

Figure 3.2 Some Characteristics of the Maquiladora Industry in Mexico

Source: Buitelaar and Padilla Pérez 2000.

Inward FDI

The manufacturing exports of developing countries are often the result of inward FDI. This is an important link between two realms of globalization we examine in this book: trade and FDI. From the point of view of poverty alleviation, the question becomes: how can the FDI-export process support domestic learning and upgrading, leading to productivity and real wage gains? One way of maximizing the benefits of FDI in the areas of employment and technology is by facilitating the use of local suppliers on the part of the foreign multinational enterprises (MNE) by developing backward links. The increased role of MNEs in an economy without significant backward links results in “enclaves,” which have little connection to the rest of the economy and little contribution beyond direct employment effects. Traditionally, the way to avoid enclave FDI was through local content requirements, but with the advent of the WTO in 1995, such requirements for local inputs became illegal.26

The key policy question for developing countries is how to foster backward links between foreign MNEs and potential local suppliers. The link promotion process involves many players, including the government, the foreign MNEs, the local suppliers, professional organizations, commercial organizations, and academic institutions. The key role of the government is one of coordination, attempting to bridge the “information gaps” among the players. We will address this issue in more detail in chapter 4 on capital flows.

Mauritius: Example of Trade-Supported Productivity Increase

The most well known group of countries that have pursued trade-supported productivity increases for long-term poverty reduction is East Asia.27 However, another notable example is the African country of Mauritius. As described by Subramanian and Roy (2003), Mauritius pursued a trade strategy that supported productivity and income gains throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Indeed, a very high openness ratio (the sum of imports and exports as a percentage of GDP) helps explain the fact that productivity gains of Mauritius in the 1990s nearly reached those of East Asia in the late 1980s to early 1990s. Export processing zones (EPZ) helped in this endeavor (box 3.1). However, as these authors note, this process of trade-supported productivity gains “would probably not have been a success, or at least not to the same extent, without the policies of Mauritius’s trading partners, which played an important role in ensuring the profitability of the export sector” (p. 223). Indeed, at least 90 percent of Mauritian exports were accounted for by preferential market access for sugar, textiles, and clothing in the European Union and the United States. Unfortunately, most low- and middle-income countries cannot count on such market access. This is the problem we turn to next.

Box 3.1 Export Processing Zones

One means by which developing countries have tried to promote the upgrading of their exports is through the use of export processing zones (EPZs). EPZs are areas of developing countries in which multinational enterprises (MNEs) can locate and in which they typically enjoy, in return for exporting the whole of their output, favorable treatment in the areas of infrastructure, taxation, tariffs on imported intermediate goods, and labor costs. EPZs have been used in many developing countries around the world. Indeed, some estimates suggest that there are over 500 EPZs in over 70 host countries. In most cases, EPZs involve relatively labor-intensive, “light” manufacturing such as textiles, clothing, footwear, and electronics and involve only basic learning. A number of studies have tried to assess EPZs from a benefit and cost framework. These studies show that in many (but not all) cases, the benefits do outweigh the costs. For example, Jayanthakumaran (2003) assessed EPZs in China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, the Republic of Korea, and Sri Lanka. He concluded that the EPZs were an important source of employment in all six of these countries. Also, in all but the Philippines, the benefits outweighed the costs. In the case of the Philippines, the infrastructure costs incurred in setting up the EPZ were too high for a net positive benefit. Thus, one cannot make general statements on the success of EPZs. They need to be examined on a case-by-case basis.

Source: Johansson and Nilsson 1997; Schrank 2001; and Jayanthakumaran 2003.

Market Access

Poverty-alleviating trade requires market access for developing-country products, whether in agriculture, manufacturing, or services. Unfortunately, poor people face substantially more trade protection than the nonpoor. Products from developing countries face at least five hurdles in gaining access to foreign markets:

- tariffs

- subsidies

- quotas

- standards and regulations

- security checks.

Tariffs

Tariffs are taxes on imports, imposed to various degrees by all countries of the world. They have the effect of reducing import levels and raising the price of the imported good within the importing country.

Tariff Levels

Poor people face higher tariffs than the nonpoor. For example, for 1998, the World Bank (2002b) compared the effective tariffs faced by poor people and by the nonpoor.28 The results were that poor people face effective tariffs that are more than twice as high as those faced by the nonpoor, an average of 14 percent as opposed to 6 percent. Poor people also face significant tariff peaks in products of export interest to them, where the tariffs are several times the average rate and can range to over 100 percent.29 There is thus a significant bias in the world trading system against poor people, the more than 2 billion individuals (a billion is 1,000 million) living on less that US$2 per day. These are the people who should be supported, not undermined, by trade policies. As it is, the global tariff system represents a regressive tax on poor people. This is true both for developing countries, where poor people on average face double the barriers, and rich countries, where poor people are most affected by the high cost of food and clothing.

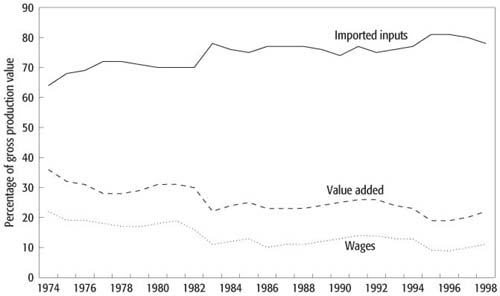

Tariff Escalation

Tariff levels faced by poor people are only one part of tariff protection. The rich countries of the world also engage in policies known to trade policy experts as tariff escalation. This means that the rich countries increase their protection with the level of processing or value added in a product. This type of protection, depicted as overall averages in figure 3.3, occurs in food, textiles and clothing, footwear, and wood products—all sectors in which the developing world has the most interest in exporting labor-intensive goods. For example, UNCTAD (2000) has shown that “effective protection doubles in the United States and Canada from the stage of leather industry to that of footwear production” (p. 10). To take another example, the tariff on cocoa beans in the European Union is 1 percent, but the tariff on chocolate is 30 percent.30 The problem with tariff escalation is that it prevents developing countries from capturing more value added domestically and from vertically diversifying their exports. It also inhibits basic and deep learning processes required for long-term productivity gains, as discussed in the previous section.

Figure 3.3 Tariff Escalation on Developing-Country Exports to Developed Countries (percent)

Source: Laird 2002.

Subsidies

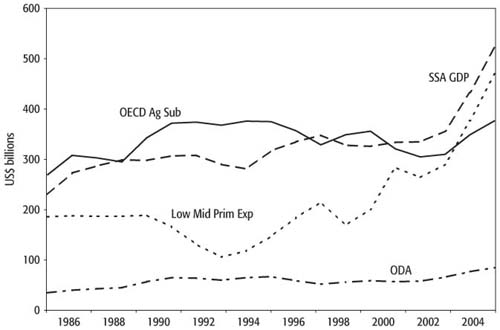

Unequal tariff protection is only one component of limited market access for developing countries. Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) indicate that, since 1986, total support to OECD agriculture has ranged between US$300 billion and US$375 billion, depending on the year. The bulk of this expenditure has been in the United States, the European Union, and Japan. These data are illustrated in figure 3.4. The solid line is total OECD agricultural subsidies between 1986 and 2004, the years for which these data are available. The dashed line is the nominal GDP of Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). For most of the past 20 years, the OECD spent more per year on agricultural subsidies than the entire GDP of Sub-Saharan Africa. The dotted line shows the primary exports of both low- and middle-income countries. Until recent years, OECD agricultural subsidies were larger than the primary exports of developing countries. Finally, the bottom dashed and dotted line is official development assistance (ODA). The OECD tends to spend on agricultural subsidies nearly five times the amount spent on ODA.

Figure 3.4 OECD Agricultural Subsidies

Source: OECD www.oecd.org/dataoecd; World Bank, World Development Indicators.

The information contained in figure 3.4 leads to one important conclusion. In the overall “subsidy war” of global agricultural trade, developing countries simply do not have anywhere near enough resources to compete. The notion that one could somehow create a level playing field by equally applying distortions is misguided. The only solution to the subsidy problem is that they be reduced. This is not to suggest that rich OECD countries do not have the right to look after their own rural areas, but when this is done, it should be in a nondistortionary manner. Such policies could be in the form of income subsidies and conservation-specific support. Indeed, from the point of view of either environmental or small-farmer considerations, most agricultural subsidies are harmful. For example, 70 percent of the nitrogen oxide pollution in the European Union is due to agriculture. And although people imagine that EU agricultural subsidies support the goat farmers and other small farmers of Provence, all but a small fraction of the subsidies in the European Union and the United States are captured by large farmers. Protectionism in the European Union, Japan and the United States has a regressive impact because citizens pay on average about US$1000 more per year for their food and textile products than they would if developing countries could have open access to their markets. Protectionism hurts poor people in both rich and poor countries.31 The detrimental impacts of subsidies and protectionism in developed countries, however, pale in comparison with their effects on the poor in developing countries.

Quotas

Throughout the period following the end of World War II and the liberalization of (some kinds) of trade under the auspices of GATT and WTO, developing countries have faced extensive quota protection in developed-country markets for their agricultural, textile, and clothing exports. These quota systems evolved beginning in the early 1960s and continued in full force through the end of the Uruguay Round in 1994. In the case of agriculture, these quotas were finally replaced by (equally protective) tariffs. In the case of textiles and clothing, the quotas were phased out by 2005, although there have been calls for their extension through 2007. The developing world has suffered through 40 years of extensive quota protection in the very sectors where their comparative advantage tends to be strongest. The case of textiles and clothing is briefly described in box 3.2.

Box 3.2 Textile and Clothing Protection

Trade protection in the textile and clothing sectors has a long history. It began in the late 1950s when Hong Kong (China), India, Japan, and Pakistan agreed to “voluntary” export restraints for cotton textile products. In 1961, the United States introduced protective quotas in cotton textile trade under the GATT-sponsored Short-Term Arrangement Regarding International Trade in Cotton Textiles (STA). In 1962, the STA was replaced by the Long-Term Arrangement Regarding International Trade in Cotton Textiles (LTA), expanding quota coverage. The LTA was renewed in 1967 and in 1970. In 1974, the Arrangement Regarding International Trade in Textiles or the Multifiber Arrangement (MFA) expanded quota coverage beyond cotton textiles. The MFA was renewed in 1977, in 1981, in 1986, and in 1991. The last extension was through 1994. By some estimates, the MFA cost the developing world about 20 million jobs in lost exports.

In April 1994, the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations concluded with the signing of the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the WTO. Developing-country concerns about the textile sector were addressed in the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC), which composed one component of the Agreement. The ATC was designed to facilitate the re-integration of the textiles and clothing sector into GATT principles for the first time since 1962. This integration was to take place in four stages, concluding with the complete integration of textiles and clothing trade into the GATT at the end of 2004.

Even with the removal of quotas beginning in 2005, textile and clothing protection will remain significant. On average, rich-country tariffs on these products are three times the average tariffs on manufacturing goods, with tariff peaks of up to 40 percent. These tariffs can have perverse effects. For example, as noted by Oxfam (2004b), “In 2001, exports from Bangladesh to the United States generated $331 million in tariff revenue for the U.S. Treasury; in the same year, net U.S. aid to Bangladesh was just $87 million” (p. 1). In addition to these high tariffs, both the United States and the European Union often employ overly restrictive rules of origin in preferential and regional trade agreements, safeguard actions, and unjustified antidumping and antisubsidy duties.

Source: Reinert 2000; Kim, Reinert, and Rodrigo 2002; and Oxfam 2004b.

Standards and Regulations

Increasing evidence suggests that developing countries face challenges in gaining market access due to standards and regulations. It is important to recognize that, whereas tariffs and quotas are in almost all cases welfare worsening for the country imposing them, this is not the case with standards and regulations, which have important public goods characteristics. As such, they should not be condemned in general. However, there is growing evidence that, in some cases at least, standards and regulations constitute important nontariff measures.

EU Food Standards

Consider the case of EU food standards. Otsuki, Wilson, and Sewadeh (2001) have examined EU standards for aflatoxin (toxic compounds produced by molds) in food exports from Africa. These authors estimated that these standards, which would reduce EU health risks by less than 2 deaths per billion per year, would decrease African exports of cereals, dried fruits, and nuts by 64 percent ($US 670 million). EU food standards are currently being tightened to include stringent reporting requirements of developing-country farmers. As reported by Wallace (2004), “new food safety regulations [are] due to come into force in the European Union in 2005. These will make it mandatory for all fruit and vegetable products arriving in the EU to be traceable at all stages of production, processing and distribution” (p. 16). EU assistance to help farmers meet these new, stringent standards that involve tracing production back to the seed is reported to be “inadequate.” Consequently, many developing-country farmers risk being closed out of this important market.32 An additional problem is that the standards are applied in a discriminatory fashion and require specialized skills and equipment beyond the capability of most of the low-income countries.

Facing Rising Standards and Increasing Regulations

If developing countries are to face increases in standards and regulations in rich-country markets, they need to be assisted with capacity building in the areas where standards are applied. We take up capacity building issues below.33

Security Checks

Since the attacks in the United States in September 2001, the exports of some developing countries have been subject to increased surveillance and security checks. For some developing countries, such as Pakistan, this has had a negative impact on sustained market access because imports into developed countries have been sourced from other countries seen as more secure. Because countries perceived to be insecure tend to be low-income, there are negative impacts on poverty of these increased security measures.

Trade Protectionism: Costs for Developing Countries

What are the costs of trade protectionism for the developing world? A number of studies have tried to assess this. To take one example, van der Mensbrugghe (2006) has considered the impact of a Doha Bound trade liberalization scenario. The welfare gains to developing countries of this liberalization scenario are estimated to be over US$86 billion.34 This is approximately the current annual value of foreign aid. The number of individuals moved out of poverty (US$2 of income per day) due to this trade liberalization exceeds 65 million. Less rigorous calculations by Oxfam (2002a) conclude that more than 100 million persons can be moved out of poverty by increased trade. Both studies conclude that a significant part of this poverty reduction would occur in Sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, a very conservative estimate of the costs of protectionism to the developing world would be an additional 60 to 100 million persons moved out of poverty—a significant number.

The Primary Product Problem

If the exports of developing countries are to support the incomes of their poor residents, the incomes generated by those exports must increase over time. Export incomes can increase in three ways: increases in export quality, increases in export quantities, and increases in export prices. Many developing countries depend on the exports of a small number of natural-resource-based goods known as primary commodities. Examples are aluminum, coffee, leather, rubber, and sugar. By their very nature, primary commodities are characterized by low levels of value added and limited room for quality improvement. Unfortunately, they are also characterized by a century-long downward trend in export prices.

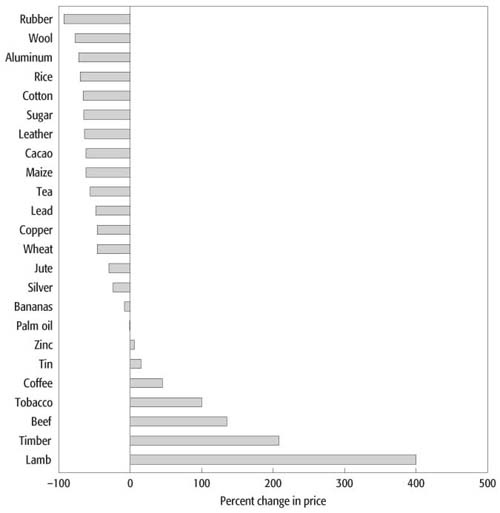

Commodity Prices

Consider figure 3.5, which presents data on primary commodity prices during the 20th century. Seventeen of the 24 primary commodities in this figure experienced declines, most of them of significant magnitude. In addition, and as reported in Ocampo and Parra (2003), an overall index of food products fell by 50 percent, an index of nonfood products fell by 15 percent, an index of metals fell by 7 percent, and the well-known Economist commodity price index fell by 60 percent.35 Evidence suggests that the period since 1980 has been characterized by particularly steep price declines.

Figure 3.5 Primary Commodity Prices in the 20th Century (percent change in price, 1900–2000)

Source: Ocampo and Parra 2003.

Commodity Price Declines

Declines in commodity prices can be disastrous for the very poor. As noted by UNCTAD (2004), “the major sin of omission in the current international approach to poverty reduction is the failure to tackle the link between commodity dependence and extreme poverty” (p. xii). For example, recent declines in coffee prices to a 30-year low (not recorded in figure 3.5) have caused death from malnutrition in Guatemala where such tragedies had been thought to have been a thing of the past. In Ethiopia, where coffee accounts for approximately one-half of export revenues, coffee farmers have been forced to shift to the production of chat, a stimulant used in the region around the Red Sea. Overall, Oxfam (2002b) estimates that the livelihoods of 25 million coffee farmers are under threat due to these recent declines in coffee prices.

Impact of Protectionist Policies

It is very difficult for developing countries to overcome these secular trends in commodity prices. However, the protectionist policies of the rich world make it more difficult than it needs to be.

- First, the agricultural subsidies discussed above contribute to declines in world prices for these goods.

- Second, tariff escalation makes it difficult for developing counties to escape primary product traps by vertically diversifying their exports along value chains toward greater value added to commodities (for example, from cacao to chocolate).

- Third, manufactures protection of the type described above (for example, in textiles and clothing) tends to concentrate developing countries in primary commodities, limiting horizontal diversification out of primary community exports, thereby exacerbating commodity price declines and contributing to the instability of export revenues.

- Finally, limited market access increases the uncertainty developing countries face with regard to future protection levels as does the unpredictable management of quotas and phyto-sanitary and other non-tariff barriers; this reduces investor confidence in both primary and non-traditional productive sectors.36

For these reasons, protection levels are doubly damaging to the world’s poor.

Impact of Foreign Aid

It is also necessary for foreign aid to take into account the limited prospects for primary commodities. Hard thinking about realistic alternatives to rural development must yield alternative routes to support incomes of the poor over the long term. This is no easy task. Until such alternatives are found, the promotion of “fair trade” commodities that ensure the maximum value for developing-country producers and help develop niche markets can play a useful role in mitigating the negative effects of price declines in some important cases.37

Trade-Related Capacity Building

Market access for developing country exports is an important step in allowing for poverty-reducing international trade. However, market access must be combined with efforts to promote export capacity in low- and middle-income countries. These capacity constraints are multidimensional and include infrastructure, market information, skills, and credit. For example, the promotion of capacity can assist “an Algerian diplomat to negotiate his country’s WTO accession, and an Indonesian civil servant to prepare a legislative proposal on copyrights, or a Mali exporter to understand business implications of the WTO Agreement on Textiles” (Kostecki 2001, p. 4). In the past, efforts to relax these constraints occurred under what was known as trade-related technical assistance. However, more recent appreciation of capacity constraints has motivated a change of focus to what is now known as trade-related capacity building. There is also a recognition that trade-related capacity building relies, at least to some significant extent, on outside assistance, making this an issue of foreign aid.

Aid and Trade: A Complementary Relationship

Most discussions of aid and trade view them as substitutes for one another, with trade being the favored of the two. It is indeed true that, from a poverty-alleviation standpoint, trade can play a much larger and sustained role than aid. That said, however, it is important to appreciate the potential complementary relationship between aid and trade, what is sometimes called “aid for trade.”38 Indeed, trade policy experts now recognize that, without such assistance, developing countries will not be able to exploit the market access that is available to them.39

Needs of Developing Countries: Capacity Building

If aid for trade is conceived of as trade-related capacity building that is responsive to developing countries’ needs, can we say something about what those needs are, at least in general terms? In international forums of various kinds, the developing countries have requested assistance in the following areas:

- Better representation in international organizations related to trade such as the WTO.

- Improving infrastructure such as roads, ports, and customs to facilitate exports.

- Upgrading negotiating capacities of trade ministries, including training in WTO legal matters and accession processes.

- Efforts to promote diversification of exports to escape the primary product problems described above.

- Upgrading systems to meet the increasing standards and regulations in developed-country exports markets.

- Developing information systems regarding potential export markets.

Efforts to meets some of these needs in the case of the least-developed countries in the form of the Integrated Framework are described in box 3.3.

Box 3.3 The Integrated Framework

One example of trade-related capacity building that focuses on the least-developed countries (LDCs) is the Integrated Framework or IF. The roots of the IF lie in the 1996 Singapore Ministerial Meeting of the WTO, which adopted a plan of action for the least-developed countries. This plan of action called for “closer cooperation between the WTO and other multilateral agencies assisting least-developed countries” in trade-related matters. Subsequently, a consensus emerged that the WTO should work with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the International Trade Centre (ITC), and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in the Integrated Framework. The precipitating event in this consensus was a high-level meeting on least-developed countries, convened by the WTO in October 1997.

Originally, the IF planned to address trade-related capacity building needs through a twofold process of needs assessment and round table discussion. Despite early enthusiasm and 40 completed needs assessments, by the end of 1999, only five roundtables had been held (Bangladesh, The Gambia, Haiti, Tanzania, and Uganda), only one of which had been considered to be successful (Uganda).

Representatives of the six IF agencies met in New York in July 2001 and issued a joint communiqué suggesting a redesign of the IF. The “new IF” involved LDCs in “mainstreaming” trade into their development policies through a “trade integration chapter” that was to be included in their Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) submitted to the World Bank and IMF. Additionally, three of the six IF agencies agreed to take lead roles: the World Bank as lead agency for “mainstreaming,” the WTO as secretariat, and the UNDP as manager of an IF Trust Fund (IFTF).

LDCs chosen to participate in the IF engage in a process known as “diagnostic trade integration studies” or DTIS. This process consists of five components: a review and analysis of the country’s economic and export performance; an assessment of the country’s macroeconomic and investment climate; an assessment of the international policy environment and specific constraints that exports from each country face in world markets; an analysis of key labor-intensive sectors where there is a potential for output and export expansion; and a “propoor trade integration strategy,” with proposed policy reforms and action plans.

Support of the IF process by the IFSC was reaffirmed in July 2003. Diagnostic studies have been undertaken in 21 countries with a further 16 in the pipeline. Financial commitments to the process continued to grow to reach US$13 million by 2005. The IF donors have summed up some of the most important goals of trade-related capacity building as follows: “We stand ready to help developing countries and LDCs engage in the multilateral trading system. Removing supply-side constraints to trade is important in generating a response to market access opportunities. We will step up assistance on trade-related infrastructure, private sector development and institution building to help countries to expand their export base.” To achieve this end, it has been estimated that a further US$200 to US$400 would be required in IF grants.

Source: The Integrated Framework for Trade-Related Technical Assistance to Least-Developed Countries, http://www.integratedframework.org/.

Promises of the Developed Countries and the WTO

It is fair to say that, while making onerous demand on the developing world to meet strenuous WTO commitments, the developed world has not met its promises to provide trade-related capacity building.40 Some initiatives have been ongoing, including the Advisory Centre on WTO Law, the Swiss-funded Agency for International Trade Information and Cooperation, and the Canadian-funded Centre for Trade Policy and Law, and the International Trade Centre’s World Tr@de Net. Despite these initiatives, evidence suggests that the major players in trade policy formation have a long way to go in providing adequate trade-related capacity building. The review of Kostecki (2001), for example, suggests that greater emphasis must be placed on genuine needs assessment and beneficiary orientation, sufficient funding, escaping bureaucratic restrictions through arm’s-length delivery organizations, and a reevaluation of the professional qualifications of capacity-building staff. There has been progress in this area, but much remains to be done if trade-related capacity building is to fulfill its promise.

Health and Safety

We mentioned in the introduction that, to help poor people, trade activities need to support forming human capital in the forms of education, training, and health. There are cases in which trade activities (both imports and exports) can actually undermine human capital by compromising the health and safety of the poor. In the case of imports, a notable example is arms, which can have disastrous impacts on the safety of citizens in the importing country. Another example is imports of toxic waste. In the case of exports, some production processes can compromise the health of the workers producing the exported products.

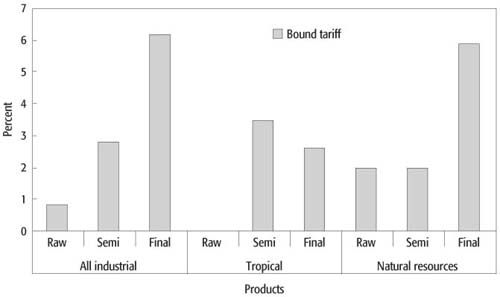

Trade in Arms

Despite the pressing human-development needs of poor countries, arms can compose a large part of low- and middle-income country imports. It is not unusual for arms to constitute 10 percent of developing country imports. As is evident in Figure 3.6, the top 20 developing-country arms importers on a per-capita basis include some of the poorest countries in the world. Civil conflicts and other forms of violence in poor countries have been estimated to result in an annual loss of at least a half million lives; conflict tends to result in development in reverse.41 Approaches to regulate the global arms trade to conflict zones therefore require serious consideration.42

Trade in Hazardous Waste

Similar health and safety issues can arise through the imports of hazardous waste, which can cause serious environmental effects as well.43 These harmful effects can be long term as well as immediate and can impose economic costs. Importing hazardous waste into poor countries is motivated by lower disposal costs in those countries, as well as by growing opposition to disposal in rich countries. In contrast to the case of arms trade, however, there is already a multilateral agreement governing hazardous waste trade—the Basel Convention on the Control of Trans-boundary Movements in Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal. This was signed in 1989 and entered into force in 1992. Although the Basel Convention has not been without controversies and disagreements, it has nevertheless been important in controlling hazardous waste trade, and it is in the process of improving compliance efforts with a central office and staff.44 Similar efforts need to be made in the area of arms trade.

Export Production Processes and Health

There are cases in which the export production processes compromise the health of workers.

The export of Nemagon, an insecticide used in banana production, is a case in point.45 This insecticide was banned in 1979 in the United States because it causes skin diseases, sterility, and birth defects. Despite this, it was used in Central American banana production through the 1980s and, in some cases, through the mid-1990s. Banana workers in Central America began to report many severe symptoms, including anencephaly, a malformation in which conceived fetuses fail to develop brains. This issue is still current. In 2004, over 1,000 affected Nicaraguan workers marched to their capital city, Managua, to demand compensation, and similar concerns were voiced in Honduras and in some cut flower export industries of Colombia and Ecuador, again involving the use of insecticides. In Ecuador, for example, Thomson (2003) reports that “studies that the International Labour Organization published in 1999 and the Catholic University issued here last year showed that women in the industry had more miscarriages than average and that more than 60 percent of all workers suffered headaches, nausea, blurred vision or fatigue.”

The health threat of pesticides that do not meet international standards in both export and domestic industries is an issue that has gained the attention of the World Health Organization (WHO). According to its estimates (2001a), nearly one-third of the pesticides marketed in developing countries do not meet international standards. These “frequently contain hazardous substances and impurities that have already been banned or severely restricted elsewhere” or “the active ingredient concentrations are outside internationally accepted tolerance limits.” The WHO calls upon all governments and international and regional organizations to adopt the World Health Organization/Food and Agricultural Organization pesticide specifications to help alleviate these health threats. Again, greater multilateral efforts are needed.

Cost of Generating Income: Health and Safety Compromised

In all these cases, a similar issue arises. Although trade activities typically generate incomes and other potential benefits for poor people, health and safety may be compromised, sometimes seriously. From a development perspective, this is a trade-off to be avoided if at all possible. The alleviation of income deprivation by increasing health deprivation is not an escape from income poverty but an exacerbation of health deprivation. In these instances, trade cannot be claimed to be fully alleviating poverty.

Illegal Trade

As Moisés Naim (2005) has highlighted, increased globalization has been associated with an escalation of illicit trade. Increased trade and movement of people, together with technological advances in financial markets, communication and transport, have been exploited by criminals to what Naim warns are unprecedented levels. He estimates that money laundering exceeds US$1 billion per year; the illegal drug trade US$800 billion; counterfeiting US$400 billion; illegal arms sales US$10 billion; cross-border human trafficking US$10 billion; and cross-border sales of art US$3 billion. These figures suggest that illegal flows account for as much as 20 percent of trade. Naim emphasizes the interconnected nature of illegal flows (for example, the money laundering of drug sales), and of legal and illegal flows (for example, drugs concealed in shipping containers). The challenge is to control illicit flows while preserving the underlying benefits of increased trade and globalization. The need for enhanced security and regulation carries the risk of adding considerable friction to the movement, not only of goods and services, but also of financial flows and migration.

Conclusions

The link between trade and poverty alleviation is not automatic. However, trade has been a powerful force for poverty alleviation in a number of ways. Exports can expand markets, helping to generate incomes for the poor. Both imports and exports can promote competition, lowering consumption and production costs in the face of monopoly (single seller) power, and raising prices for suppliers in the case of monopsony (single buyer) power. Both imports and exports can support productivity improvements through access to new machinery and contact with discerning international customers. Imports are also important for health aspects of human development, because many medical supplies need to be imported to combat deprivations of health.

Trade Protectionism: A Barrier to Alleviating Poverty

The possibility of exports helping to alleviate poverty is significantly curtailed by trade protectionism in rich countries. This occurs in the form of tariffs, subsidies, quotas, standards, and regulations. Even conservative estimates of the potential gains from reducing protectionism in rich countries are many times the size of annual foreign aid flows. Rich-country protectionism poses a significant barrier to poverty alleviation, not to mention the overall participation of the developing world in the global economy.

Commodity Price Declines

Developing countries relying on the export of primary commodities have suffered from a century-long decline in primary commodity prices that continues to this day. Although export diversification is one way to lessen the effects of such commodity price declines, the impact of these secular trends is exacerbated by rich-country protectionism. Agricultural subsidies and tariff escalation are particularly pernicious in this regard.

Capacity Building

For trade to benefit poor people, increases in market access for developing countries must be combined with trade-related capacity building. These capacity-building efforts are often prerequisites for developing countries to overcome supply constraints, and this is an area where trade and aid act as positive complements. As new thinking in development policy stresses, capacity building should be beneficiary-driven and partnership-based, strive to develop local capacities and skills, and place trade issues in a broader development perspective.46 These include considerations of the broader business and investment environment (the “software”—including questions of health, education, governance, and corruption) as well as the physical infrastructure (the “hardware”—including roads, power, water, and ports). Both these broad areas of action are vital for governments and aid agencies alike.

Trade: Impact on Health and Safety of the Poor

In some cases, trade can have a very direct and negative impact on the health and safety of the poor. This occurs with imports of arms and toxic waste and also with production processes of exports that compromise the health of workers. In each of these cases, concrete, multilateral steps need to be taken to ensure that trade does not compromise poverty reduction and human development but supports it.

Trade Liberalization

We have shown in this chapter that trade reform in both rich and developing countries has a vital role to play in ensuring that globalization benefits the poor. The movement of economies toward more trade-oriented profiles typically involves processes of trade liberalization, often under the auspices of the WTO, the World Bank, the IMF, or regional trade agreements. As emphasized by Harrison, Rutherford, and Tarr (2003); Winters, McCulloch, and McKay (2004); and UNCTAD (2004), the transition costs associated with these reforms can be significant and may actually worsen poverty for some classes of households. For this reason, as developing countries consider the role that increased trade can play in poverty alleviation, they need to guard against the real possibility of increasing the poverty of some groups. Safety nets (social protection), complementary antipoverty programs, and direct compensation might be necessary to achieve poverty-alleviating transitions.47 Again, trade reform is vital but should be placed within a comprehensive approach to overcoming poverty.

Notes

1. The fact that the trade–poverty alleviation link is not automatic has also been stressed by UNCTAD (2004) in the case of the least-developed countries.

2. In this chapter, we are in broad agreement with the assessment of Oxfam (2002a), that “In itself, trade is not inherently opposed to the interests of poor people. International trade can be a force for good, or for bad…. The outcomes are not pre-determined. They are shaped by the way in which international trade relations are managed, and by national policies” (p. 28).

3. To make this observation is not to downplay the exploitation that can often occur in export sectors, such as 14-hour days. Labor standards do matter. But it is decidedly not the case that exploitation is absent from agricultural day labor. We will discuss these issues in more detail, especially health and safety concerns.

4. Readers are probably familiar with the notion of a monopolist—a single seller in a market that can increase the price of its product above the competitive level to the detriment of buyers in the market. A monopsonist is a single buyer in a market that can lower the price of the product it purchases below the competitive level to the detriment of sellers in the market.

5. See Kapur and Ramamurti (2001), for example. These authors show that the large and fast-growing software market within the United States with its sophisticated software buyers has contributed significantly to the competitiveness of the Indian software sector. The remaining issue, however, is the extent to which the expansion of incomes generated by the Indian software industry supports the incomes of poor Indians. In this instance the answer might be “only a little.”

6. See Cragg and Epelbaum (1996), chapter 5 of de Ferranti and others (2002), Gindling and Robbins (2001), and Robbins and Gindling (1999). For the case of South Africa, see Edwards (2004). More generally, Winters, McCulloch, and McKay (2004) note that “trade liberalization may be accompanied by skill-biased technical change, which can mean the skilled labor may benefit relative to unskilled labor” (p. 75).

7. A value chain is a series of value-added processes involved in the production of a good or service.

8. To be fair, there are also market access issues between developing countries that are becoming increasingly important as what international economists call “South-South trade” increases. See, for example, World Bank (2002b) and Laird (2002).

9. See, for example, Reinert (2004).

10. See, for example, Lipton (2005).

11. Minot and Goletti (2000) report that “Rice production in Vietnam is characterized by small irrigated farms, multiple cropping, labor-intensive practices, and growing use of inorganic fertilizer, though there are substantial regional differences” (p. xi). Average farm size is only 0.25 hectares.

12. See Minot and Goletti (1998, and 2000) as well as chapter 2 of Oxfam (2002a). The latter does note that “the advances (in Vietnam) have been unevenly distributed, and many of the poorest producers lack access to the marketing infrastructure and productive resources needed to take advantage of export opportunities” (p. 53). Similar conclusions are provided by Jenkins (2004). On the impact on child labor, see Edmonds and Pavcnik (2002).

13. Zohir (2001) did raise concerns about the effect of garment-sector work on women’s health and the increased risk of harassment. We take up health and safety issues in their own right later in the chapter.

14. On the procompetitive effects of trade, see Markusen (1981).

15. A 2000 study by the TeleCommons Development Group (TDG) of Canada found that “the consumer surplus from a single phone call to Dhaka, a call that replaces the physical trip to the city, ranges from 2.64 percent to 9.8 percent of the mean monthly household income. The cost of a trip to the city ranges from 2 to 8 times the cost of a single phone call, meaning real savings for poor rural people of between 132 to 490 Taka (USD 2.70 to USD 10) for individual calls” (Grameen Phone, www.grameenphone.com ).

16. See Bayes, von Braun, and Akhter (1999).

17. Again, see Bayes, von Braun, and Akhter (1999).

18. See Winters (2000) and Poulton and others (2004). Recent economic setbacks in Zimbabwe have dramatically erased gains associate with trade liberalization.

19. See Winters (2000) and Jayne and others (1995).

20. For a review of the evidence on trade liberalization and productivity, see Winters, McCulloch, and McKay (2004).

21. As emphasized by Bruton (1998), “For the development objective, the main role of exports is its possible contribution to the acquisition of new technical knowledge and consequent increase in productivity through contact with foreign importers combined with the pressures of strong competition” (p. 924). The same can be said of imports. There is a tradition in international economic policy of claiming a great deal for exports in terms of resulting productivity gains. For a critical review of this tradition, see chapter 2 of Rodrik (1999).

22. As emphasized by Szirmai (2005), “the most important contribution of education is indeed ‘learning to learn’” (p. 221).

23. On the presence of productivity increases in agriculture, see Martin and Mitra (2001). On the role of services in supporting productivity increases in manufacturing, see Francois and Reinert (1996).

24. See, for example, Lall (1998).

25. It is important to emphasize that basic education is only a necessary but not a sufficient condition for learning. Indeed, measures of human capital such as average years of schooling explain very little of the variation among developing countries in either low-technology manufacturing exports or high-technology manufacturing exports.

26. The equivalent of local content requirements is still included in government procurement, however. One example is the South African government’s agreement for military aircraft with Airbus. See Odell (2004).

27. See, for just one example, Rodrigo (2001).

28. The assumption here is that poor people earn their incomes from labor-intensive merchandise production, while the nonpoor earn their incomes across the full array of economic activities. The “poor” are defined as those living on less than US$2 per day. See chapter 2.

29. This point is made by Laird (2002), among others.

31. See Messerlin (2001); Goldin and Winters (1995); and www.oecd.org/statisticsdata.

32. See also Barnes (2004).

33. For a further discussion of standards and regulations issues, see Wilson (2002). This author notes that “relatively little is known about the cost impacts of differing product standards and how they affect exporters in developing countries” (p. 436).

34. This figure includes “static” gains only; “dynamic” gains that reflect growth effects are much higher. These dynamic gains reflect alleged productivity gains that are the result of increased exports. However, the magnitude of these dynamic gains is uncertain.

35. For the century and a half between 1850 and 2003, The Economist’s commodity price index fell by 80 percent. See The Economist (2004a).

36. Francois and Martin (2002) note that foreign market access security “serves to reduce uncertainty for foreign investors about the ability of an economy to link itself with the global economy and hence to generate returns that can ultimately be repatriated” (p. 545).

37. See Raynolds (2000) and references therein. The “fair trade” designation is the responsibility of the Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International (FLO). While we support the goals of this effort with respect to maximizing the incomes of poor people, we do not embrace some of its general, antimarket statements.

38. The subject of aid for trade actually overlaps with two other chapters of this book: chapter 5 on aid and chapter 7 on ideas. Aid for trade and trade-related capacity building are development ideas that are effected through foreign aid.

39. One example is the generalized system of preferences (GSP) granted the least-developed countries (LDCs) by the developed world. As observed by Inama (2002), “Almost 30 years of experience with trade preferences, and particularly with the GSP schemes, have largely demonstrated that the mere granting of duty-free market access to a wide range of LDCs’ products does not automatically ensure that the trade preferences will be effectively utilized by beneficiary countries” (p. 114).

40. As noted by Kostecki (2001), “Most of the WTO provisions calling for … technical assistance are ‘best endeavour’ promises which are not binding on donor countries” (pp. 11–12).

41. Former World Bank president James Wolfensohn (2002), for example, highlighted that “the world’s leading industrial nations provide nearly 90 percent of the multibillion dollar arms trade—arms that are contributing to the very conflicts that all of us profess to deplore, and that we must spend additional monies to suppress” (p. 12).

42. The Commission for Africa (2005) and the United Kingdom Foreign Secretary have recently highlighted the need for further progress in this area, as have organizations such as Oxfam, Amnesty International, and the International Action Network on Small Arms. See, for example, www.iansa.org.