Ch. 13

SHARKS

You is sharks, sartin; but if you gobern de shark in you, why den you be angel; for all angel is not’ing more dan de shark well goberned.

Fleece, “Stubb’s Supper”

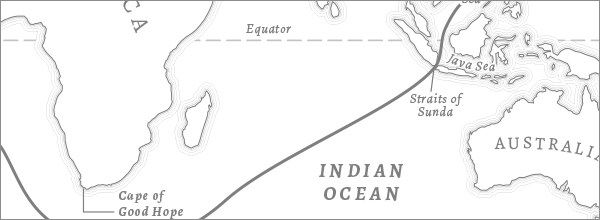

After the sea-ravens and the brit and witnessing the giant squid in all its enormous, nebulous whiteness, the men of the Pequod continue eastbound in the Indian Ocean. As Queequeg predicted, they soon see sperm whales. Stubb kills the first one of the voyage. They lash it alongside. Night falls. Now enter the sharks.

Introductions to shark field guides and other quick studies of the American perception of sharks often explain that it was twentieth-century attacks on coastal swimmers and the stories about shipwrecked soldiers mauled and eaten by sharks while floating at sea in World War II that kicked off an American cultural fear and hatred of these animals—an automatic fear response when an author or filmmaker sends a dorsal fin gliding into a scene. The correlation with sharks was then expanded and cemented by the likes of Peter Benchley’s novel Jaws (1974)—which has distinct nods to Moby-Dick—then far more so by Steven Spielberg’s film version the following year. A flood of sensationalized documentaries followed, bleeding into today’s “Shark Week.” Our current fear of sharks, these authors suggest, is the result of a recently learned, mostly unreasonable cultural fear of these animals. This learned fear theory of the American perception of sharks might be valid for nearly all of us who never come into contact with these animals in our professions or recreational life, but the chronology of this cultural antagonism fails to account for the American whalemen in previous centuries. For those aboard whaleships, those who had regular relationships with deep ocean sharks, familiarity bred contempt. Whalemen hated sharks, reserving for them a level of cruelty that they inflicted on no other animal. And they brought their stories home.

ISHMAEL’S SHARKS AND SHARKISHNESS

Throughout Moby-Dick, Ishmael uses the word and image of sharks to evoke lawlessness, danger, and ferocity. Ishmael says that whalemen have explored “the heathenish sharked waters” of the Pacific, beyond where no other mariners had dared. Starbuck soliloquizes on his “heathen crew” that was “whelped somewhere by the sharkish sea.” And along with swordfish and whales, sharks are part of the “murderous thinkings of the masculine sea.”1

In other parts of his storytelling, Ishmael uses sharks to evoke nightmares and ghosts. The crunching teeth of sharks are the stuff of the sailors’ bad dreams, evoked by Ahab’s crunching the decks over their heads with his ivory leg. “Insatiate sharks” swim around a whale corpse floating off in the distance, becoming a ghostly myth and metaphor for the dangers of religious orthodoxy. Sharks swim around a dead whale that Fedallah and Ahab float beside one night: the sharks sounding, with biblical allusions, “like the moaning in squadrons . . . of unforgiven ghosts.” Only in “The Whiteness of the Whale” does Melville specify a kind of shark, the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), with which he furthers the ghostly imagery and elevates the power of his White Whale. Ishmael’s White Shark lurks in “white gliding ghostliness.” He explains in a footnote that in French this shark is called Requin, sharing the name of the “funereal music” of the requiem at the Catholic Mass for the dead.2

Ishmael gives sharks their most significant role in the closely aligned chapters “Stubb’s Supper,” “The Shark Massacre,” and “The Monkey-rope.” The whalemen have killed their first sperm whale and lashed it alongside. Sharks scavenge and tear off pieces of the bloody carcass. Ishmael explains that if they were in the equatorial region where sharks were more common, the whale would be but a skeleton by morning, but since the ship is not, Stubb takes the first watch while the rest of the crew sleep so they may rest for the labor of processing the whale the next day. Still, the ship is surrounded by “thousands on thousands of sharks.”3

In “Stubb’s Supper,” Ishmael describes the sights and sounds of sharks scavenging on a whale as he directly connects these sharks with Stubb, who has awoken the cook, Fleece, to prepare him a whale meat steak. Stubb prefers the whale especially rare, just as the sharks eat their rare meat in the water, “mingling their mumblings with his own mastications.” Ishmael also associates these sharks with dogs around humans at a table, or a scene of battle, waiting in the shadows while men kill each other as warriors or slavers:

Though amid all the smoking horror and diabolism of a sea-fight . . . the valiant butchers over the deck-table are thus cannibally carving each other’s live meat with carving-knives all gilded and tasseled, the sharks, also, with their jewel-hilted mouths, are quarrelsomely carving away under the table at the dead meat; and though, were you to turn the whole affair upside down, it would still be pretty much the same thing, that is to say, a shocking sharkish business enough for all parties; and though sharks also are the invariable outriders of all slave ships crossing the Atlantic, systematically trotting alongside, to be handy in case a parcel is to be carried anywhere, or a dead slave to be decently buried.4

Ishmael continued that meandering, encircling sentence to explain that rarely do sharks collect in such numbers anywhere at sea than around a whaleship at night. Then he punctuates the paragraph with a snap: “If you have never seen that sight, then suspend your decision about the propriety of devil-worship, and the expediency of conciliating the devil.”5

In “The Shark Massacre,” Ishmael turns to the sharks themselves, down in the water. While Stubb works on his, the sharks work on their own meal. Queequeg and another sailor lower lanterns over the side and stand on the cutting stage to try to kill and hack away at the sharks in order to reduce the loss of blubber. Looking over the rail at night to watch this feeding is a scene of Gothic horror:

These two mariners, darting their long whaling-spades, kept up an incessant murdering of the sharks, by striking the keen steel deep into their skulls, seemingly their only vital part. But in the foamy confusion of their mixed and struggling hosts, the marksmen could not always hit their mark; and this brought about new revelations of the incredible ferocity of the foe. They viciously snapped, not only at each other’s disembowelments, but like flexible bows, bent round, and bit their own; till those entrails seemed swallowed over and over again by the same mouth, to be oppositely voided by the gaping wound.6

This is the most grotesque vision in all of Moby-Dick. It’s more graphic than anything you’ll read in Frankenstein (1818), Dracula (1897), or Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym (1838). Ishmael gives a dead shark the ability to clank its jaws closed, nearly chomping off Queequeg’s hand. “It was unsafe to meddle with the corpses and ghosts of these creatures,” Ishmael says as Queequeg wonders what sort of heathen God would create a shark.7

At the end of Moby-Dick, sharks have a different role in the drama. On the third day of the final chase, the “unpitying sharks” lurk and crunch at the oars as Ahab’s boat tries to stroke after the White Whale. The sharks follow and snap at Ahab’s boat alone. While they pursue Moby Dick, Ahab wonders aloud whether the sharks want to feast on the whale or on him. Eco-critically minded readers might interpret here that the sharks are instead trying to protect the whale, their own apex predator leader.

The final cameo of the sharks in Moby-Dick is in the final image of the novel. In “The Epilogue” Ishmael floats alone on his coffin: “the unharming sharks, they glided by as if with padlocks on their mouths.”8

So Melville fed the period fear and contempt for sharks, writing of these fish as a ghastly, fierce, and cannibalistic metaphor and also as a very real masticating menace to the men of the Pequod. He saved his most gruesome, horrific imagery in the novel for sharks. Yet in other ways, Melville wrote of these predators in a more tempered manner than did his whalemen contemporaries and even the naturalists ashore, describing his sharks with a surprising, subtle degree of sympathy. Melville had Ishmael and Fleece explain that humankind is no more ethical than sharks, and perhaps even more cruel and insatiable. In Moby-Dick, humans are more sharkish than the sharks, first hinted by the departure of the pilot fish from sharkish Ahab. As ichthyologists today learn more and more about sharks, we see that once again, Melville was sneakily, surprisingly, accurate when read from a twenty-first-century biological perspective. For example, Ishmael’s sharks will eat humans on purpose only if the people are already dead: “A thing altogether incredible were it not that attracted by such prey as a dead whale, the otherwise miscellaneously carnivorous shark will seldom touch a man.”9

THE WHALEMAN’S PERCEPTION OF SHARKS IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Francis Allyn Olmsted, whom we’ve already turned to regarding his accounts of albatross, pilot fish, and squid, was the American answer to the British surgeon-naturalists Beale and Bennett. Only a few weeks older than Melville, he boarded a whaleship in 1839 out of New London, Connecticut. Similar to Dana, who in 1834 left Harvard to go to sea in part to cure his bad eyesight, Olmsted had just graduated Yale and boarded a ship for his own health. Olmsted was in much worse shape than Dana, however. In his Incidents of a Whaling Voyage, he refers to himself as an “invalid,” but he doesn’t specify his symptoms beyond “a chronic debility of the nervous system.” Olmsted shipped at the age of twenty on the whaleship North America as a gentleman-naturalist. He returned in February 1841 from his voyage aboard a merchant ship, which dropped anchor off Sandy Hook, New Jersey, as Melville was barely a month outward bound from New Bedford aboard the Acushnet. Olmsted hustled home to New Haven and sent out his narrative, which was snatched up immediately and published the same year. Back at Yale, he earned a medical degree with a dissertation on the role of how narcotics helped to cure insanity. Then he got so sick again that he tried to go to sea once more, but this time he returned home to die less than a week after he turned twenty-five.10

Notably different from most other naturalists and whalemen authors at the time, Olmsted did his own drawings for his narrative. His images in Incidents of a Whaling Voyage were the first commercially published illustrations of American whaling (see later fig. 42).11

Olmsted was a broad-minded field naturalist who was equally comfortable with a gun, a dissecting kit, or a scientific paper in his hands. Olmsted’s father was a professor at the University of North Carolina who moved his family to Connecticut to take a post at Yale in mathematics and natural philosophy. Also an author of text books and an inventor, he cultivated a wide range of interests that included studies of hail stones and shooting stars. So Francis grew up in a household that valued science and a careful, empirical eye. In contrast to the bowing formality of Surgeon Beale, Olmsted in his narrative often slipped in slivers of self-deprecatory, subtle humor. Although he had not yet had any medical training, the captain and men aboard the North America soon began referring to him as the “doctor.” He was put in charge of the ship’s medical chest, with which he did his best to care for his shipmates and the locals that they met who requested aid. When the ship made its first port stop in Ecuador after five months at sea, Olmsted wrote that since the locals wanted confirmation of their health: “It is a singular fact that in proportion to the beauty of the fair applicant, a longer time was required to count the pulsations of her arm.” When crossing the equator on the way home, Olmsted put a piece of string across the spyglass so the passengers’ kids could see “the line.”12

Olmsted often described great abundance in the South Pacific: “Among the various amusements which make the time pass away pleasantly aboard ship, catching fish is one of the most agreeable. Vast schools of fish frequently accompany ships for several days in succession, and whalers are often surrounded for month after month by countless hosts of the finny tribe.” Olmsted caught a range of fish himself. In order to catch sharks, in particular, he used a stout hook with chain.13

One April day to the west of the Galápagos Islands, the crew killed a large male sperm whale and rowed it back to the ship. Lashed to the side, the whale was left overnight. In order to rest, the crew tolerated a collection of sharks, just as does the crew of the Pequod. The next day Olmsted captured six or seven “Peaked-Nose Sharks,” each about seven feet long. He said these were also known as the “Blue shark.” He gave a detailed account of their fins, teeth, tail, and five “orifices” forward of the side fin. Olmsted summed up his shipmates’ perspective:

The shark in all his varieties, is regarded with inveterate hatred by the sailor, and is considered a legitimate subject for the exercise of his skill in darting a lance or spade, to which this savage animal is admirably adapted from his apparent insensibility to pain. At the repeated gashes he receives from these formidable instruments, he manifests the utmost indifference and calm composure, and even with a large hook in his mouth he still continues to exercise his voracious propensities. Aboard whale ships, sometimes, upon the capture of a shark during the process of trying out, he is drawn out of the water by two or three men, and a gallon or more of boiling oil is poured down his open mouth, a most cruel act, but defended on the ground that “nothing is too bad for a shark.”14

In the same breath that he called them “ravenous monsters,” Olmsted relayed, just as Ishmael does, that this shark rarely bites humans unless they put themselves in harm’s way in the flurry of the bloody, blubbery water.

This does not mean that American whalemen did not worry that sharks would prey on them intentionally. When they stepped aboard their first ships, their perception, taken as a whole, was likely the same as how most of us feel today: intellectually we know the chance of shark attack is rare, but that doesn’t mean we’re not terrified by the prospect. And as we do today, when whalemen in the 1800s discussed drowning or death in the water it was often associated directly with sharks, whether they saw them alongside or imagined their immediate appearance. For example, greenhand-artist Robert Weir associated sharks with death in his journal at the start of his first voyage: “We are far very far out of sight of land—of sweet Ameriky. I was sent aloft to the lookout for whales + whatnots—And oh! how dreadfully [sea]sick I was. saw two sharks, one about 12 ft long + the other 5 or 6 ft. I felt very much tempted to throw myself to them for food.” Later Weir drew in his journal a detailed illustration of sharks preying on a whale as the men cut into the blubber (see earlier fig. 14).15

Sometimes the whaleman’s fear of sharks was warranted, even when they did not have a dead whale alongside. Owen Chase, for example, in his 1821 account of his small-boat journey after the wreck of the Essex, describes a shark chomping at the oars of a whaleboat. As the men were slowly dying of exposure and starvation, Chase said that one night “a very large shark was observed swimming about us in a most ravenous manner, making attempts every now and then upon different parts of the boat, as if he would devour the very wood with hunger; he came several times and snapped at the steering oar, and even the stern-post.” Beale, Colnett, and others, like Ishmael in the final chase, also described sharks chomping at the whaleboat’s oars.16

Ishmael’s gruesome description in Moby-Dick of sharks cannibalizing each other and feeling no pain when hacked or sliced by the men’s spades matches the descriptions of Melville’s other contemporaries and likely his own observations when looking over the rail when processing whales at sea. J. Ross Browne led his Etchings of a Whaling Cruise with his own personal illustration of ferocious sharks feeding on a whale carcass alongside. Browne told the story of a shark that was coming up on a man trying to insert the hook into the dead whale while it was floating alongside, almost exactly as Melville would later write in “The Monkey-rope.” Browne described a shipmate from above lopping off the tail of the shark with one slice from his cutting spade. “Strange to say,” Browne wrote, “the greedy monster did not appear to be particularly concerned at this indignity, but, sliding back into his native element, very leisurely swam off, to the great apparent amusement of his comrades, who pursued him with every variety of gyrations.”17

A few years later, the Reverend Cheever described how he witnessed sailors skinning sharks alive in order to get the skin for sandpaper. Similar to Queequeg’s experience, Cheever wrote: “One [shark] that we hauled upon deck, after it was cut open, and the heart and all the internal viscera were removed would still flap and thrash with its tail, and try to bite it off. The heart was contracting for twenty minutes after it was taken out and pierced with the knife.” Cheever also relayed a story of a gutted shark with its tail chopped off that was still able to swim away. “Sailors . . . kill them whenever they can,” Cheever said, “and there is little wonder, considering they are so likely to be themselves eaten by this greedy ranger.” Mary Brewster, a captain’s wife, recorded the whaleman’s hatred for sharks, too, explaining in her journal that the men sometimes caught them to use the oil for their boots. On her second voyage in 1848, she wrote that one day off the Azores the crew caught a large shark, which they killed and threw right back over. She wrote: “The delight of the sailor is to kill every one they can get.” Men on whaleships sometimes ripped out the teeth, jaws, and vertebrae of sharks for their craftwork on board. Some, as Olmsted described, wrote of torturing the animals, cutting off their tails and throwing them back alive, or even sticking a steel rod down a living shark’s throat before tossing it back overboard.18

THE LANDLUBBER’S PERCEPTION OF SHARKS IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Images of cannibalistic, ravenous sharks that felt no pain made their way back to popular works ashore. Melville’s Penny Cyclopædia simply, unemotionally listed the known species of sharks along with the rays, organized with morphological descriptions under the heading of their taxonomic family at the time, the Squalidæ. Other popular science works, however, such as Samuel Maunder’s A Treasury of Natural History (1852), declared that sharks “devour with indiscriminating voracity almost every animal substance, whether living or dead.” Good’s Book of Nature said the shark was “the most dreadful tyrant of the ocean,” capable of devouring everything. Good wrote that the “white shark” can be thirty feet long and 4,000 pounds, and can “swallow a man whole at a mouthful.” (The longest trusted record of a great white is about 19.5 feet.) Thousands of people in Boston, likely including Melville, viewed John Singleton Copley’s famous painting Watson and the Shark (1778), which hung on exhibit at the Boston Athenaeum in 1850. The painting depicts a naked boy in the water only seconds away from the jaws of an enormous great white shark-monster. This was based on a true story of an English teenager named Brook Watson who was bathing off a small boat in Havana Harbor. A shark bit off his leg beneath the knee. Watson, who would later be the Lord Mayor of London, had a peg leg for the rest of his life.19 (See fig. 27.)

FIG. 27. Detail of J. S. Copley’s Watson and the Shark (1778), a painting scholars believe Melville saw while writing Moby-Dick.

Even the preeminent scientists of the mid-nineteenth century were no less emotional or factually conservative about sharks. Baron Georges Cuvier, in the volume on fish that Melville owned, described the white shark as a man-eater and just beneath the sperm whale, which was the apex of all predators. As Ishmael described in “The Shark Massacre,” Cuvier wrote in his work of science: “The white shark . . . is so impatient to pass its half-digested food, to make room for more, that, as Commerson observed, the intestines are frequently forced out a considerable distance from the anus. So great indeed is the gluttony of this animal, that, as Vancouver relates, when harpooned, and no longer able to defend itself, it is sometimes torn to pieces by its companions.”20

SHARK TAXONOMY

In his earlier novel Mardi, Melville not only wrote of the killing of a hammerhead from a small boat (the scene with the pilot fish), but also he composed a lovely little chapter setting up that scene in the story. It’s called “Of the Chondropterygii, and other uncouth Hordes infesting the South Seas.” It has some ideas similar to those that he would express a few years later in “Cetology,” “Brit,” and other scenes in Moby-Dick. Here in Mardi Melville wrote of all the wonders of the ocean unknown to people ashore: “I commend the student of Ichthyology to an open boat, and the ocean moors of the Pacific. As your craft glides along, what strange monsters float by. Elsewhere, was never seen their like. And nowhere are they found in the books of the naturalists.” Here Melville wrote brief, anthropomorphized descriptions of the different types of sharks, those identified by whalemen. Melville’s common names of sharks align with the narratives of the time and the logbooks of experienced whalemen. Men on whaleships often identified different species of sharks that they saw scavenging on whale meat or that they saw from the rails of their boats and ships. The men at times just recorded them generically as “sharks,” but typical common names included the white shark, the “bone shark,” the “brown shark,” the “shovel-nosed shark,” and, as Olmsted wrote, the “Peak-nosed Shark,” also known as the “Blue Shark.”21 (See earlier fig. 3.)

Today over five hundred species of sharks have been named and agreed upon by modern taxonomists, with more classified each year. By the time Moby-Dick was published, naturalists had named only a little over half of these sharks. About a dozen of the known species today are the large pelagic sharks. They are in the families Laminidae and Carcharhinidae, the latter of which are still known as the requiem sharks. All large pelagic sharks will opportunistically scavenge on a sick or recently dead marine mammal and might commonly follow a small boat inquisitively. What whalemen called the shovel-nosed was one of the hammerhead varieties (Family Sphyrinidae). The “bone” shark came from the same word that they used to describe baleen. These would be the big-mouthed plankton-filtering sharks, the whale shark (Rhincodon typus) and the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus). Olmsted and Melville’s peak-nosed/blue shark corresponds to what today’s ichthyologists still call the blue shark (Prionace glauca), which does indeed have a longer, pointed snout. Mariners might have also used this common name when they saw a mako (Isurus sp.) or even a great white, which can be blue or black dorsally. The whalemen’s “brown shark” is the trickiest in retrospect. Bennett described it around a whale carcass and said they never got larger than eight feet, with the scientific name Squalus carcharias. In Mardi Melville wrote that the “ordinary” Brown Sharks, “the vultures of the deep,” were the most common around a whale carcass, and this shark would snap at their oars, and even swim in “herds.” His mariners might’ve been speaking of a dozen different shark species here, perhaps most commonly the oceanic whitetip shark (Carcharhinus longimanus) or the great white.22

A SHARK EXPERT REVIEWS ISHMAEL’S SHARKS

At his lab beside Monterey Bay, I show shark expert David Ebert a sailor’s illustration labeled “brown shark,” but it doesn’t have enough detail other than to suggest it likely wasn’t a great white. Ebert says the most likely species to feed on carcasses mid-ocean and around the equator would be blue sharks, oceanic whitetips, occasionally great whites, tiger sharks (Galeocordo cuvier), and several Carcharhinus sharks, which include the silky sharks (C. falciformis), Galápagos sharks (C. galapagensis), dusky sharks (C. obscurus), bull sharks (C. leuchas), and bronze whaler sharks (C. brachyrus).23

Ebert is a native Californian who grew up in the water around great whites and then spent years studying large predator sharks off South Africa. He returned to Monterey Bay, in part because of the productivity from the ocean canyon and the large populations of marine mammals. The bay is a lively ground for sharks, especially great whites.

Ebert’s lab at Moss Landing is in a building lined with stuffed marine mammals and skeletons of seabirds and whales, and even the library has an enormous shark mural. Ebert is the author of shark field guides and scientific papers, and he’s a regular on Shark Week documentaries. He has seen sharks feeding on whales, including one time from the cliffs of South Africa when he watched a dozen or so great white sharks thrashing into a dead southern right whale. Ebert explains that bloody fish guts can work to attract sharks, but he’s found that dolphin and whale blubber is an even better attractant. The sharks smell the scent from the slick of oil. He says, “You just see these fins pop up on the horizon in the slick.”24

Ebert supports Ishmael’s observations about shark cannibalism: “That’s true. Definitely happens. The sharks are very precise when they’re feeding on stuff, but sometimes if one gets wounded or winged or injured, then the others will pile on and start eating him or her.” Ebert says there’s a hierarchy among sharks at a carcass, within a species and among others, say, with a great white shark pushing out or even “snacking” on a blue shark that’s in its way. “I’ve seen the events where the smaller sharks will come in initially and then the bigger sharks will come in with their teeth and graze them, along with other behaviors, to get them to leave, to say, hey, the big boys are in now. But usually they’re pretty focused on the whale.” Ebert compares the sharks to hyenas in the wild, in the same way that Ishmael compares them to dogs.25

Regarding Ishmael’s depiction of sharks’ indifference to pain, Ebert confirms that these animals can survive serious wounds and tremendous loss of tissue, and, yes, the musculature can still respond after a shark is technically dead. “People think, My god, you can’t kill this thing, but it is dying. It’s just an involuntary reflex—so you got to be careful because they still snap, but not consciously. Best thing to do is sever the vertebral column—or the brain if you can get into it.”

Ebert explains that for all the negative press that came with Jaws, it also helped stimulate interest and funding for shark research and even some conservation, too. Unprompted, he makes an Ishmaelian point to emphasize the importance of learning from the commercial fishermen and the whale-watch captains who have the most experience out in Monterey Bay. Ebert says he’s always prodding his students to go out and talk to these men and women.

I ask Ebert about the status of shark populations. Ishmael’s “thousands upon thousands” of sharks around Stubb’s sperm whale carcass is surely fictional hyperbole, but, is it likely that more large sharks did swim around the global ocean in the mid-nineteenth century, based on the accounts of early mariners?

Ebert explains that facts about past shark abundance are hard to come by, yet shark specialists and fisheries biologists who study present populations in relation to past or healthy ocean ecosystems are confident there have been significant losses in both the numbers and the size of sharks since Melville’s mid-nineteenth century. For example, historians believe that human hunting practically eradicated the large plankton-eating basking sharks from Massachusetts Bay by the 1830s. Late eighteenth-century explorers such as James Colnett and George Vancouver reported enormous sharks in the Pacific, animals eighteen to twenty feet long, which is easy to discount as exaggerations, but the men could measure them well in comparison to their small boats. Part of the challenge is that few nineteenth-century or even twentieth-century scientists or fishermen ever actually counted sharks. They were only considered bycatch or a nuisance. And no recent scientists have yet done DNA work to estimate historical populations. Today, the shark-fin trade still thrives despite international regulations, and small sharks are a regular target for food and for bait for higher value fisheries. Sharks of all sizes are regularly killed as bycatch by the hundreds of thousands of tons each year, unmanaged—and particularly post-Jaws, the large sharks are now targeted in recreational fisheries, although there is more value now in cage diving and photography trips.26

Today’s commercial fishermen, like their nineteenth-century whalemen counterparts, often compete with scavenging sharks. They experience the same frustrations with sharks eating their bait or their catch as did nineteenth-century whalemen. In 2010 Linda Greenlaw wrote about the destruction that blue and mako sharks inflicted on her swordfishing gear or the fish that they’d caught on the line. Over the years Greenlaw watched her shipmates pounding sharks with ice mallets, slicing them up in pieces, and setting the sharks on fire with lighter fluid, some of which she’d even participated herself when she was younger. She wrote that she’d grown out of that kind of hatred of sharks and discouraged it with her crew, but she expected that it continued on other boats: “Maiming, torturing, and killing sharks out of frustration and some weird sense of retaliation and revenge were bound to occur.”27

A 2003 study in Nature found that more than ninety percent of the biomass of all predatory fish, sharks included, have been fished out of the global ocean since before the Industrial Age, when Ahab first rolled into the Pacific. In 2014 shark specialists for the IUCN estimated that over a quarter of all sharks and rays are currently in danger of extinction. The blue shark is “near threatened”; the great white shark is “vulnerable”; the great hammerhead shark is “endangered”; and scientists do not yet have enough information to assess the oceanic whitetip shark.28

On the other end of things, however, Ebert explains that the great white shark is exceptionally well-protected today. With the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, elephant seals, eared seals, and true seals are all making a comeback, especially in areas like Monterey Bay. This food source has brought back great white shark populations.

Motioning out toward the water, Ebert says: “You get tired of trying to count white sharks around here.”

Only a week after I meet with Ebert a man is attacked by a great white shark while spearfishing with his father at the south end of Monterey Bay. As is commonly the case with these sorts of attacks, the shark bites a couple times at the legs and then backs off. The young man, named Grigor Azatian, bleeds profusely. Trained professionals just happen to be on the beach. They apply a tourniquet and save his life.29

A SECOND SHARK EXPERT REVIEWS ISHMAEL’S SHARKS

While sharks feeding on a whale carcass was a common vision for tens of thousands of whalemen in the nineteenth century, few people have witnessed this since. It’s rarely described in any scientific literature.

Chris Fallows is a wildlife photographer and a guide for great white shark observing and cage diving off South Africa. He often works with field scientists, during which he is one of the few who has actually observed and photographed events where great whites scavenge dead whales (see plate 10). Fallows once observed sharks eating a near-term fetus that they’d bitten out of a dead Bryde’s whale. He’s seen firsthand the circular bites in whale meat from great whites, which, just as Ishmael says, appear as near-perfect countersunk circles.

One extraordinary behavior that Fallows and his colleagues have witnessed is that sharks regularly regurgitate chunks of whale blubber, seemingly, they theorize, to make room for other bites of higher calorie whale blubber or meat, with “higher energy yield chunks.” Other researchers off South Africa have watched a thirteen-foot female white shark feed on its own regurgitated whale meat. Was this what Cuvier had heard about, and what Ishmael described in his gruesome scene of sharks eating their own innards?30

On the sound of sharks feeding on a carcass, Fallows says: “Yes, yes, yes. It is a sound that never leaves you. It sounds like the noise of a bellow used to fan a fire. Coupled with the fatty spray, blood, and smell—it is an experience that you never forget.”31

SHARKS AND SLAVERY

Through a twenty-first-century lens, Melville’s depiction of Fleece in “Stubb’s Supper” seems mocking, if not hostile, toward racial equality. Fleece is a comic slave. As he gets relentlessly ordered about by Stubb, commanded to give a speech to animals, Fleece appears so foolish that he doesn’t know his own age or that the United States is his country.

In 1973 a literary scholar named Robert Zoellner wrote of “Stubb’s Supper”: “Over a century after Melville wrote these lines, one can only feel embarrassment at such evidence—pervasive in nineteenth-century American literature from Fenimore Cooper on—that possession of moral sensitivity and high creative gifts does not necessarily arm one against the prejudices and stereotypical thinking of one’s culture.” In other words, we’d like Melville to have been an active abolitionist. He was not.32

Melville was, however, more enlightened on race than might first appear, especially by contrast to others of his day. Francis Allyn Olmsted, for example, wrote disdainfully of the native Hawaiians. The comments of 1940s whalemen in their journals about their African-American shipmates, such as those by John F. Martin, are often ugly and offensive. American whaleships were diverse islands and one of the rare workplaces where merit took precedence over skin color, but they were certainly not beyond the racism on land. As the new United States struggled to mend its divisions over slavery, Melville did see the institution as evil. Some today read Moby-Dick as prescient of the Civil War, with the Pequod, the ship of state, sunk because of its obsession with race and whiteness. Only four years after Moby-Dick, even closer to the Civil War, Melville engaged directly with the slave trade and its horrors with his novella Benito Cereno. Melville, along with his father-in-law, the Chief Justice in Massachusetts, seemed to have worried that to emancipate the millions of slaves in one sign of the pen would be too dangerous and chaotic for America. He hoped that the southern states would soon end slavery on their own. Within this historical context, Melville does not go as far as we might wish, but he does have something profound and progressive to say on both race and nature, which he centered, more safely, on sharks. He does not, unfortunately, directly address immoral hatred among humans, yet with these marine predators, in a proto-Darwinian way, Ishmael decenters man in Moby-Dick, regardless of race or ethnicity, and explores the similarities between the main drivers of human and nonhuman animals.33

It is Queequeg who first teaches Ishmael cultural empathy in the novel. The Polynesian hero saves at least two human lives over the course of the story. He then saves Ishmael’s life indirectly with his coffin. Zoellner wrote that Melville wanted us to read Queequeg as the human embodiment of a shark. Queequeg is nomadic, a superior swimmer and hunter, and a cannibal with “filed and pointed teeth.” A good harpooner needs to be “pretty sharkish,” Peleg explains. In “Cetology” Ishmael lays the groundwork to sympathize with sharks and equate them to the dark-side of humans: “For we are all killers, on land and on sea; Bonapartes and Sharks included.” Later in “The Monkey-rope,” when Queequeg balances on a dead whale in order to insert the blubber hook, balancing between the sharks and the men, Ishmael says of Queequeg, as he is tied physically and metaphorically to the sharkish hero: “Are you not the precious image of each and all of us men in this whaling world? That unsounded ocean you gasp in, is Life; those sharks, your foes; those spades, your friends; and what between sharks and spades you are in a sad pickle and peril, poor lad.”34

The two African-American characters in Moby-Dick, Pip and Fleece, are not treated as heroically as Queequeg. Nor is the African Daggoo, forced to be Flask’s harpooner, treated altogether favorably. Dagoo is the one sent down to get the steak in “Stubb’s Supper.” Yet if you could remove the dialect, for example, Fleece’s sermon is brilliant. He directs and extends this discussion on what is cruel and indifferent in nature, in comparison to what is more evil and dangerous in man. Fleece delivers, Zoellner argues, one of the major morals of Moby-Dick with vocabulary and rhetoric that is beyond most of the other crew members: embrace what is innate, Fleece says, what is natural. Fleece has a thorough understanding of Scripture, even though he claims to Stubb that he’s never been in a church. Though he listens to Stubb out of necessity, Fleece is clearly the better person throughout this interaction, which I find hard to believe that this would have escaped a nineteenth-century reader. In direct contrast to the Calvinist sermon in New Bedford, which argues that people must bend to God’s wishes, Fleece preaches the governance of our evil thoughts, universal equality, and charity for the weak. The cook shows sympathy for sharks in the way Ishmael has learned to revere the morality of Queequeg.35 Fleece says:

Your woraciousness, fellow-critters, I don’t blame ye so much for; dat is natur, and can’t be helped; but to gobern dat wicked natur, dat is de pint. You is sharks, sartin; but if you gobern de shark in you, why den you be angel; for all angel is not’ing more dan de shark well goberned. Now, look here, bred’ren, just try wonst to be cibil, a helping yourselbs from dat whale. Don’t be tearin’ de blubber out your neighbour’s mout, I say. Is not one shark good right as toder to dat whale?36

Fleece then settles on the still more forgiving path, which accepts that sharks will be sharks, men will be men, and we must forgive that which is innate. Fleece understands that Stubb is more shark than the sharks—because he could know better, but does not act morally. The real “shocking sharkish business” is war and violence and hatred. Perhaps even whaling itself, or the broader hunting of marine animals. Melville certainly wanted to make clear in “Stubb’s Supper” that by the shocking business, he also meant the American institution of slavery.

Even more subtle and more shocking to the twenty-first-century reader, is that there was nothing fictional about sharks in the 1800s scavenging on sick and dead men, women, and children who were thrown off slave ships by slave traders or on those African people who jumped off to commit suicide to escape the horror or to gain a final sliver of autonomy. The terror of sharks eating dead African people in the sea was used regularly by abolitionists to expose what was happening on the Middle Passage. This vision of sharks as man-eaters was in the nineteenth-century public consciousness. In 1840, for example, one of Melville’s favorite artists, J. M. W. Turner, painted The Slave Ship with a nightmarish vision of blood, hands, shackles, and shark fins.37

With all that in mind, it’s still a disappointment to the modern reader that Ishmael displays racial prejudice with his suggestion in “The Chase—Third Day” that the sharks might have been more attracted to the flesh of Fedallah and his crew, “infidel sharks” themselves, even if he pulled this directly from Baron Cuvier’s comments that great white sharks used their keen sense of smell toward killing black men over white, because men with darker skin were “more odoriferous.” Ishmael does not correct this or suggest it ironically.38

In “Stubb’s Supper” Fleece has lived long enough to accept the evil in man. He has survived years of degradation. He does not rely on traditional religion, pleads ignorance of his connection to a country that would enslave people, and seeks solace in a peaceful afterlife, a deliverance from an angel. Fleece, like Pip, has been the victim of the sharkish evil in mankind. Fleece has made peace. Pip goes mad. They both know how this voyage in pursuit of the White Whale is going to end.

Starbuck, meanwhile, still wonders whether the good in man might prevail: that Ahab will not lead them all to their death. Even this is connected with sharks. Many scenes later in “The Gilder,” gazing over the rail at a lovely Pacific sunset, Starbuck seems to heed Fleece’s sermon and remain with Christianity in the hopes that everything will turn out all right with this hunt. Starbuck prays that humankind, as a group and as an individual, can overcome, can govern, our innate sharkishness, despite what has been proven to be true over and over again throughout history. Starbuck soliloquizes while looking into the sea: “Loveliness unfathomable, as ever lover saw in his young bride’s eye!—Tell me not of thy teeth-tiered sharks, and thy kidnapping cannibal ways. Let faith oust fact; let fancy oust memory; I look deep down and do believe.”39