Vowels can’t be described in the same way as consonants. For vowels there’s always considerable space between the articulators so that in terms of manner of articulation all vowels are approximants. Nor can we effectively use place of articulation – all we can do is distinguish broadly whether the front, centre or back of the tongue is raised towards the roof of the mouth. Finally, our third variable (voicing or energy of articulation) is of little help. Vowels are typically voiced, so that there are no voiced/ voiceless or fortis/lenis contrasts.

It is possible to use another means of description, namely acoustic data, and acoustic phoneticians have now made enormous advances in this area. But obtaining such information and interpreting it still involves considerable time and effort. In language teaching, dialect research, and many other branches of practical phonetics, a speedy and reasonably accurate way of describing vowels is what is actually required.

The most generally used description of vowel sounds is based on a combination of articulatory and auditory criteria, and takes into account the following physical variables:

Finally, we have a non-physical variable which operates in a large number of languages:

5Duration.

Change in the shape of the tongue is perhaps the most important of all these factors. Let’s first examine the variable of tongue height, namely how close the tongue is to the roof of the mouth. For some vowels, it is very easy to see and feel what is going on, as you can test for yourself in the following two activities.

58

Say the English vowel /aː/, as in PALM. Put your finger in your mouth. Now say the vowel /iː/ (as in FLEECE). Feel inside your mouth again. Look in a mirror and see how the front of the tongue lowers from being close to the roof of the mouth for /iː/ to being far away for /aː/. Now you know why doctors ask you to say ‘ah’ when they want to see inside your mouth; the tongue is at its lowest when you say /aː/.

Now say these English vowels: /iː/, as in FLEECE, /εː/, as in square, /æ/, as in TRAP. Can you feel the tongue moving down? Then say them in reverse order: /æ/, /εː/, /iː/. Can you feel the tongue moving up?

As the tongue lowers, the oral cavity opens and increases in size. Consequently, the oral cavity is bigger for /aː/ than it is for /iː/, and as a result it produces a lower-pitched resonance.

60

Now take another set of English vowels and say them a number of times: /aː/, as in PALM, /ɔː/, as in THOUGHT, /uː/, as in GOOSE.

For the vowel /aː/ in PALM, the tongue is fairly flat in the mouth. For /ɔː/ in thought, the back of the tongue rises, and for /ui/ in goose is closer again. We cannot see or feel the back of the tongue as easily as the front, and the lip-rounding for /ɔː/ and /uː/ obscures our view. But X-ray photography (and similar imaging techniques) confirm the raising of the back of the tongue for vowels like /ɔː/ and /uː/.

This provides us with an important aspect of vowel description. If the upper tongue surface is close to the roof of the mouth (like /iː/ in FLEECE and /uː/ in GOOSE) the sounds are called close vowels. Vowels made with an open mouth cavity, with the tongue far away from the roof of the mouth (like /æ/ in TRAP and /aː/ in PALM), are termed open vowels.

We also need to know which part of the tongue is highest in the vowel articulation. If the front of the tongue is highest (as in the first type /iː/ and /εː/), we term the sounds front vowels. If the back of the tongue is the highest part, we have what are called back vowels (the second type, like /ɔː/ and /uː/).

Although we can look into the mouth cavity, it is impossible to view directly what is happening in the pharynx – but this can be observed with X-ray imaging and similar techniques. As a consequence, we know that the open vowels like /aː/ have the tongue root pushed back so that the pharynx cavity is small. For the other open vowels, and to an extent for all back vowels, the pharynx cavity is reduced in size.

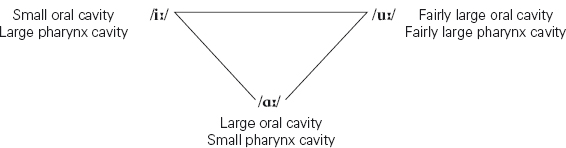

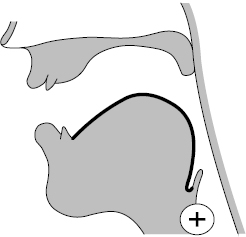

Figure A6.1Relative sizes of oral and pharynx cavities in vowel production

It was not until early in the twentieth century that a reasonably accurate system of describing and classifying vowels was devised. In 1917, the British phonetician Daniel Jones (1881–1967) produced his system of cardinal vowels (often abbreviated to CVs), a model which is still widely employed to this day.

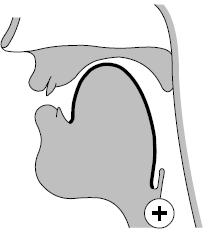

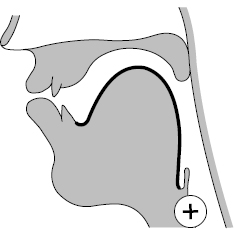

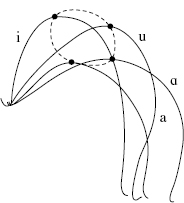

For any vowel, the tongue must be arched into a hump (termed the tongue arch), as illustrated in Figures A6.2–A6.5. We can always distinguish the highest point of the tongue arch for any vowel articulation. There is an upper vowel limit beyond which the surface of the tongue cannot rise in relation to the roof of the mouth – otherwise friction will be produced. The vowels at the upper vowel limit are the front vowel [i] and the back vowel [u].

Fairly large oral cavity Fairly large pharynx cavity /ia/ /ua/

61

Say a close front vowel, e.g. /iː/ in FLEECE. Now try to put your tongue even closer to the roof of your mouth. You will hear friction. Do the same for /uː/ in GOOSE. Once again a kind of fricative will be the result.

Figure A6.2Tongue arch for [i]

Figure A6.3Tongue arch for [u]

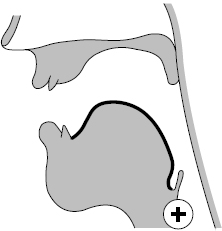

Figure A6.4Tongue arch for [a]

Figure A6.5Tongue arch for [ɑ]

There is also a lower vowel limit beyond which the tongue cannot be depressed. This gives us two other extreme vowels – a front vowel [a] and a back vowel [a].

We have now established the closest and most front vowel [i]; the closest and most back vowel [u]; the most open and most front vowel [a]; the most open and most back vowel [a].

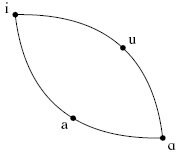

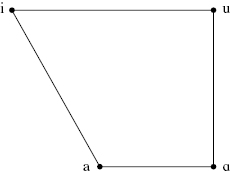

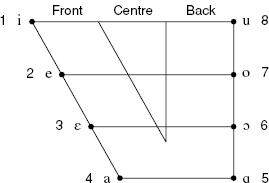

Figure A6.6 shows the superimposed tongue-arch shapes for the vowels [i u a a]. In each case, the highest point of the tongue has been indicated by a black dot. If we then link up these dots, as shown on the diagram with a dashed line, then we arrive at an oval shape – rather like a rugby football (or its American football equivalent). This is termed the vowel area, indicating the limits for vowel production (see Figure A6.7). For the sake of simplicity, we can straighten out the lines to form a four-sided figure, termed the vowel quadrilateral, as shown in Figure A6.8. Other vowels have been estimated auditorily (i.e. by ear) at roughly equal steps related to assumed tongue height. This gives four intermediate vowels – two front [e ε] and two back [o ɔ]. The full series of eight sounds is termed the primary cardinal vowels (named after the cardinal points of the compass: North, South, East, West). The quadrilateral is then for convenience divided up by lines as in Figure A6.9. The resulting figure is termed the vowel diagram.

Figure A6.8Vowel quadrilateral

Figure A6.9Primary cardinal vowels shown on a vowel diagram

What the cardinal vowel model provides is a mapping system which presents what is essentially auditory and acoustic information in a convenient visual form. The approach can be faulted in some respects, mainly in that no account is taken of the pharyngeal cavity. Nevertheless, linguists have found it a very useful way of dealing with vowel quality for many practical purposes. The cardinal vowel model has been adopted by phoneticians all over the world and, in 1989, a vowel diagram closely based on it was introduced on to the International Phonetic Alphabet symbol chart. The full revised 2005 version is illustrated on p. 332.

Note the labelling system for the cardinal vowels:

[i]: front close |

[e]:front close-mid |

[ε]:front open-mid |

[a]:front open |

[u]:back close |

[o]:back close-mid |

[c]:back open-mid |

[a]:back open |

In older textbooks, you may find the terms ‘half-close’ for close-mid and ‘half-open’ for open-mid.

Below, we give some rough indications of what the primary cardinal vowels sound like (what is technically termed vowel quality). To do so, we use, for comparison, average vowel qualities in familiar European languages:

[i]: French vie |

[e]:German See |

[ε]:French crème |

[a]:French patte |

[u]:German Schuh |

[o]:German so |

[c]:English awe |

[a]:unrounded English box |

It must be emphasised that the above are intended only as rough guides. The quality of the vowels in natural languages has considerable variation from one accent to another. To overcome this problem and in order to define the cardinal vowel qualities, Jones made a series of audio recordings, and these have served as a standard for other phoneticians using the system. A recording of the CVs by Daniel Jones himself can be heard if you visit this website: http://wwwp.honeticsu.clae.du/course/chapter9/ cardinal/cardinalh.tml.

Listen to the recording of the primary cardinal vowels on your audio CD; get to know them so that you can recognise them and reproduce them with ease. At the same time, learn to associate the vowel with its number and symbol and its place on the diagram. Listen to the vowels again, and repeat them, this time using your mirror and noting carefully the shape of the lips.

Change of lip shape is also a significant factor in producing different vowel qualities. The main effects of lip-rounding are: (1) to enlarge the space within the mouth; (2) to diminish the size of the opening of the mouth. Both of these factors deepen the pitch and increase the resonance of the front oral cavity. The lip shapes of the primary CVs follow the pattern typically found in languages worldwide. Front and open vowels have spread to neutral lip position, whilst back vowels have rounded lips (see Figure A6.10). (The UPSID survey of world languages, carried out by the University of California, has shown that over 90 per cent of front and back vowels are unrounded and rounded respectively; Maddieson 1984.)

The shape of the lips can be shown on vowel diagrams by means of the following lip-shape indicators:

Unrounded,  e.g. /ex/ in FACE

e.g. /ex/ in FACE

Rounded,  e.g. /ok/ in GOAT in many American varieties.

e.g. /ok/ in GOAT in many American varieties.

Although front unrounded vowels are the norm, nevertheless a number of languages (including many spoken in Europe) also have rounded front vowels; this goes for French, German, Dutch, Finnish, Hungarian, Turkish and the major Scandinavian languages. For example, French has the rounded front vowels /y ø œ/, as in tu ‘you’, peu ‘little’ and neuf ‘nine’; German rounded front vowels include /yː øː œ/, as in Stühle ‘chairs’, Goethe (name), Götter ‘gods’. Unrounded back vowels are much less common but are, for instance, to be heard in some languages of the Far East, like Japanese and Vietnamese. To cover these cases, a set of secondary cardinal vowels was devised, with reverse lip positions (i.e. front rounded, back unrounded) and these can be found on the official IPA chart (p. 332). For many purposes, it is only necessary to be familiar with three front rounded vowels as shown in Figure A6.11.

Figure A6.10Lip shape of primary cardinal vowels

Figure A6.11Front rounded cardinal vowels

63  Track 21

Track 21

Listen to the recording of the three secondary cardinal vowels /y ø œ/; get to know them so that you can recognise them and reproduce them with ease. Look in a mirror when you pronounce them to check that your lips are rounded.

You can find more information on the cardinal vowels in the Handbook of the International Phonetic Association (1999: 10–13).

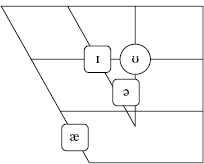

Other vowels are now included in the latest version of the vowel diagram incorporated into the International Phonetic Alphabet. The most important of these is the central vowel [ə] (termed schwa after the name of the vowel in Hebrew and similar to the bonus vowel of English). In addition, the following vowels are significant because of their frequent occurrence in languages: centralised CV 2 [I] (similar to KIT) and centralised CV 7 [Ʊ] (similar to FOOT). See Figure A6.12. Another vowel shown is a front vowel between CVs 3 and 4, namely [æ] – termed ‘ash’ (from the name for the letter in Old English). This sound is similar to General American TRAP.

If the positions of the tongue and lips are held steady in the production of a vowel sound, we term it a steady-state vowel. In other books you may encounter the terms ‘pure vowel’ or ‘monophthong’ /'mDnəfθDŋ/ (Greek for ‘single sound’; note the spelling with phth). If there is an obvious change in the tongue or lip shape, we term the vowel a diphthong (meaning ‘double sound’ in Greek, pronounced /'dIfθDŋ/; note again the spelling with phth). For a sound to be considered a diphthong, the change – termed a glide – must be accomplished in one movement within a single syllable without the possibility of a break. Apart from steady-state vowels, most languages also have a number of diphthongs; this goes for English and for other European languages, e.g. Dutch, Danish, German, Spanish and Italian. French is the best-known example of a language which is usually analysed as having only steady-state vowels.

The starting-point of a diphthong is shown in the usual way and the direction of the tongue movement is indicated by an arrow. Figure A6.13 illustrates by means of a cross-section the change in tongue position for the English diphthong /aI/ as in PRICE. This corresponds to an arrow on a vowel diagram.

To allow for possible change in lip shape in diphthongs, two additional lip-shape indicators are employed:

From unrounded to rounded, e.g. /əu/ in GOAT

From unrounded to rounded, e.g. /əu/ in GOAT

From rounded to unrounded, e.g. /ɔI/ in CHOICE

From rounded to unrounded, e.g. /ɔI/ in CHOICE

Note that the indication goes from left to right as in handwriting. (These lip-shape indicators were devised by J. Windsor Lewis 1969.)

Nasal vowels, produced with the soft palate lowered (see Section A4), are found in many languages all over the world. European languages with nasal vowel phonemes include French (see Activity 64), Portuguese and Polish. These sounds are common in African languages (for example, Yoruba, spoken in Nigeria) and are also to be heard in a European language now spoken in South Africa – Afrikaans (see Activity 65).

64  Track 22

Track 22

Listen to your audio material and practise making the nasal vowels in the French words given here: brun ‘brown’ /br i/, train ‘train’ /tr

i/, train ‘train’ /tr /, banc ‘bench’ /b

/, banc ‘bench’ /b /, bon ‘good’ /b

/, bon ‘good’ /b /. (Most present-day speakers of standard French have no contrast /

/. (Most present-day speakers of standard French have no contrast / –

–  /, using /

/, using / / for both.) Compare the oral vowels: boeuf ‘ox’ /bœf/, très ‘very’ /trε/, bas ‘low’ /ba/, beau ‘beautiful’ /bo/.

/ for both.) Compare the oral vowels: boeuf ‘ox’ /bœf/, très ‘very’ /trε/, bas ‘low’ /ba/, beau ‘beautiful’ /bo/.

65  Track 23

Track 23

Listen to these Afrikaans sounds on your CD: kans ‘chance’ /k s/, mens ‘human being’ /m

s/, mens ‘human being’ /m s/, ons ‘we, us, our’ /

s/, ons ‘we, us, our’ / s/.

s/.

Duration is merely the time taken for any sound. But measuring sounds in isolation only gives us absolute values. Duration is only of linguistic significance if one considers the relative length of sounds, i.e. the duration of each sound has to be considered in relation to that of other sounds in the language.

Many languages have a phonemic contrast of longer vs. shorter duration in vowel sounds, although very often this is combined with differences of vowel quality. This is true of English where the checked vowels like /I/ are shorter than the free vowels like /iː/ (see Sections A2 and B3). Similar phonemic pairs are found in, for example, German, Dutch and the Scandinavian languages.

The following system can be used for vowel description. The areas of the vowel diagram are designated in the way shown in Figure A6.14.

Figure A6.14Areas of the vowel diagram

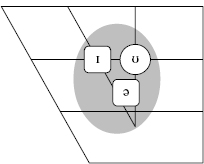

Figure A6.15Central vowel area (indicated by shading)

We shall also distinguish between central vowels (i.e. those in or near the central-mid position of the diagram, Figure A6.15) and peripheral vowels (i.e. those around the edges, or periphery, of the vowel diagram).

66

Transcribe phonemically, showing intonation groups and sentence stress, and using weak and contracted forms wherever possible.

Transcription Passage 6

Alice opened the door and found that it led into a small passage. She knelt down and looked along the passage into the loveliest garden you ever saw. How she longed to get out of that dark hall, and wander about among those beds of bright flowers and cool fountains. But she was not able even to get her head through the doorway. ‘And then, if my head would go through,’ thought poor Alice, ‘it would be of very little use without my shoulders. Oh, how I wish I could shut up like a telescope! I think I could, if I only knew how to begin.’ For, you see, so many out-of-the-way things had happened lately, that Alice had begun to think that nothing was really impossible.