At this point, let’s sort out some basic terminology. The study of sound in general is the science of acoustics. We’ll remind you that phonetics is the term used for the study of sound in human language. The study of the selection and patterns of sounds in a single language is called phonology. To get a full idea of the way the sounds of a language work, we need to study not only the phonetics of the language concerned but also its phonological system. Both phonetics and phonology are important components of linguistics, which is the science that deals with the general study of language. A specialist in linguistics is technically termed a linguist. Note that this is different from the general use of linguist to mean someone who can speak a number of languages. Phonetician and phonologist are the terms used for linguists who study phonetics and phonology respectively.

We can examine speech in various ways, corresponding to the stages of the transmission of the speech signal from a speaker to a listener. The movements of the tongue, lips and other speech organs are called articulations – hence this area of phonetics is termed articulatory phonetics. The physical nature of the speech signal is the concern of acoustic phonetics (you can find some more information about these matters on the recommended websites, pp. 313–15). The study of how the ear receives the speech signal we call auditory phonetics. The formulation of the speech message in the brain of the speaker and the interpretation of it in the brain of the listener are branches of psycholinguistics. In this book, our emphasis will be on articulatory phonetics, this being in many ways the most accessible branch of the subject, and the one with most applications for the beginner.

In our view, phonetics should be a matter of practice as well as theory. We want you to produce sounds as well as read about them. Let’s start as we mean to go on: say the English word mime. We are going to examine the sound at the beginning and end of the word: [m].

There’s a tremendous amount to say just about this single sound [m]. First, it can be short, or we can make it go on for quite a long period of time. Second, you can see and feel that the lips are closed.

2

Produce a long [m]. Now pinch your nostrils tightly, blocking the escape of air. What happens? (The sound suddenly ceases, thus implying that when you say [m], there must be an escape of air from the nose.)

3

Once again, say a long [m]. This time put your fingers in your ears. Now you’ll be able to hear a buzz inside your head: this effect is called voice. Try alternating [m] with silence [m . . . m . . . m . . . m . . . ]. Note how the voice is switched on and off.

Consequently, we now know that [m] is a sound which:

Consequently, we now know that [m] is a sound which:

is made with the lips (bilabial)

is made with the lips (bilabial)

is said with air escaping from the nose (nasal)

is said with air escaping from the nose (nasal)

is said with voice (voiced).

is said with voice (voiced).

Do the same for a different sound – [t] as in tie.

4

Say [t] looking in a mirror. Can you prolong the sound? If you put your fingers in your ears, is there any buzz? If you pinch your nostrils, does this have any effect on the sound? (The answer is ‘no’ in each case.)

is made with the tongue-tip against the teeth-ridge 1 (alveolar)

is made with the tongue-tip against the teeth-ridge 1 (alveolar)

has air escaping not from the nose but from the mouth (oral)

has air escaping not from the nose but from the mouth (oral)

is said without voice (voiceless).

is said without voice (voiceless).

A word now about the use of different kinds of brackets. The symbols between square brackets [ ] indicate that we are concerned with a sound and are called phonetic symbols. The letters of ordinary spelling, technically termed orthographic symbols, can either be placed between angle brackets <m> – or, as in this book, they can be printed in bold, thus m.

Human beings are able to produce a huge variety of sounds with their vocal apparatus and a surprisingly large number of these are actually found in human speech. Noises like clicks, or lip trills – which may seem weird to speakers of European languages – may be simply part of everyday speech in languages spoken in, for example, Africa, the Amazon or the Arctic regions. No language uses more than a small number of the available possibilities but even European languages may contain quite a few sounds unfamiliar to native English speakers. To give some idea of the possible cross-linguistic variation, let’s now compare English to some of its European neighbours.

For example, English lacks a sound similar to the ‘scrapy’ Spanish consonant j, as in jefe ‘boss’. This sound does exist in Scottish English (spelt ch), e.g. loch, and is used by some English speakers in loanwords and names from other languages. A similar sound also occurs in German Dach ‘roof’, Welsh bach ‘little’ and Dutch schip ‘ship’, but not in French or Italian. German has no sound like that represented by th in English think. French and Italian also have a gap here but a similar sound does exist in Spanish cinco ‘five’ and in Welsh byth ‘ever’. English has no equivalent to the French vowel in the word nu ‘naked’. Similar vowels can be heard in German Bücher ‘books’, Dutch museum ‘museum’ and Danish typisk ‘typical’, although not in Spanish, Italian or Welsh. We could go on, but these examples are enough to illustrate that each language selects a limited range of sounds from the total possibilities of human speech.

In addition we need to consider how sounds are patterned in languages. Here are just a few examples.

Neither English nor French has words beginning with the sound sequence [kn], like German Knabe ‘boy’ or Dutch knie ‘knee’. Many centuries ago English did indeed have this sequence, which is why spellings like knee and knot still exist.

Neither English nor French has words beginning with the sound sequence [kn], like German Knabe ‘boy’ or Dutch knie ‘knee’. Many centuries ago English did indeed have this sequence, which is why spellings like knee and knot still exist.

Both French and Spanish have initial [fw], as in French foi ‘faith’ and Spanish fuente ‘fountain’; this initial sequence does not occur in English, Dutch or Welsh.

Both French and Spanish have initial [fw], as in French foi ‘faith’ and Spanish fuente ‘fountain’; this initial sequence does not occur in English, Dutch or Welsh.

English has many words ending in [d], contrasting with others ending in [t], e.g. bed and bet. This is not true of German where, although words like Rad ‘wheel’ and Rat ‘advice’ are spelt differently, the final d and t are both pronounced as [t]. Dutch is similar to German in this respect, so that Dutch bot ‘bone’ and bod ‘bid’ are said exactly the same. The same holds true for Russian and Polish, whereas French, Spanish and Welsh are like English and contrast final [t] and [d].

English has many words ending in [d], contrasting with others ending in [t], e.g. bed and bet. This is not true of German where, although words like Rad ‘wheel’ and Rat ‘advice’ are spelt differently, the final d and t are both pronounced as [t]. Dutch is similar to German in this respect, so that Dutch bot ‘bone’ and bod ‘bid’ are said exactly the same. The same holds true for Russian and Polish, whereas French, Spanish and Welsh are like English and contrast final [t] and [d].

Speech is a continuous flow of sound with interruptions only when necessary to take in air to breathe, or to organise our thoughts. The first task when analysing speech is to divide up this continuous flow into smaller chunks that are easier to deal with. We call this process segmentation, and the resulting smaller sound units are termed segments (these correspond very roughly to vowels and consonants). There is a good degree of agreement among native speakers on what constitutes a speech segment. If English speakers are asked how many speech sounds there are in man, they will almost certainly say ‘three’, and will state them to be [m], [æ] and [n] (see pp. 15–16 for symbols).

Segments do not operate in isolation, but combine to form words. In man, the segments [m], [æ] and [n] have no meaning of their own and only become meaningful if they form part of a word. In all languages, there are certain variations in sound which are significant because they can change the meanings of words. For example, if we take the word man, and replace the first sound by [p], we get a new word pan. Two words of this kind distinguished by a single sound are called a minimal pair.

5 (Answers on Website)

Make minimal pairs in English by changing the initial consonant in these words: hate, pen, kick, sea, down, lane, feet.

Let’s take this process further. In addition to pan, we could also produce, for example, ban, tan, ran, etc. A set of words distinguished in this way is termed a minimal set.

Instead of changing the initial consonant, we can change the vowel, e.g. mean, moan, men, mine, moon, which provides us with another minimal set. We can also change the final consonant, giving yet a third minimal set: man, mat, mad. Through such processes, we can eventually determine those speech sounds which are phono-logically significant in a given language. The contrastive units of sound which can be used to change meaning are termed phonemes. We can therefore say that the word man consists of the three phonemes /m/, /æ/ and /n/. Note that from now on, to distinguish them as such, we shall place phonemic symbols between slant brackets / /. We can also establish a phonemic inventory for NRP English, giving us 20 vowels and 24 consonants (see ‘Phonemes in English and Other Languages’ below).

But not every small difference that can be heard between one sound and another is enough to change the meaning of words. There is a certain degree of variation in each phoneme which is sometimes very easy to hear and can be quite striking. English /t/ is a good example. It can range from a sound made by the tip of the tongue pressed against the teeth-ridge to types of articulation involving a ‘catch in the throat’ (technically termed a glottal stop). Compare /t/ in tea (tongue-tip t) and /t/ in button (usually made with a glottal stop).

Ask a number of your friends to say the word button. Try to describe what you hear. Is there an obvious t-sound articulated by the tongue-tip against the teeth-ridge? Or is the /t/ produced with glottal stop? Is there a little vowel between /t/ and /n/? Or does the speaker move directly from the /t/ to /n/ without any break? And is it the same with similar words, like kitten, cotton, and Britain? Now try the same thing with final /l/, as in bottle, rattle, brittle. Do you notice any difference in people’s reactions to the use of glottal stop in these two groups of words?

Each phoneme is therefore really composed of a number of different sounds which are interpreted as one meaningful unit by a native speaker of the language. This range is termed allophonic variation, and the variants themselves are called allophones.

Only the allophones of a phoneme can exist in reality as concrete entities. Allophones are real – they can be recorded, stored and reproduced, and analysed in acoustic or articulatory terms. Phonemes are abstract units and exist only in the mind of the speaker/listener. It is, in fact, impossible to ‘pronounce a phoneme’ (although this phrasing is often loosely employed); one can only produce an allophone of the phoneme in question. As the phoneme is an abstraction, we instead refer to its being realised (in the sense of ‘made real’) as a particular allophone.

Although each phoneme includes a range of variation, the allophones of any single phoneme generally have considerable phonetic similarity in both acoustic and articulatory terms; that is to say, the allophones of any given phoneme:

usually sound fairly similar to each other

usually sound fairly similar to each other

are usually (although not invariably) articulated in a somewhat similar way.

are usually (although not invariably) articulated in a somewhat similar way.

We can now proceed to a working definition of the phoneme as: a member of a set of abstract units which together form the sound system of a given language and through which contrasts of meaning are produced.

A single individual’s speech is termed an idiolect. Generally speaking, it is easy for native speakers to interpret the phoneme system of another native speaker’s idiolect, even if they speak a different variety of the language. Problems may sometimes arise, but they are typically few, since broadly the phoneme systems will be largely similar. Difficulties occur for the non-native learner, however, because there are always important differences between the phoneme system of one language and that of another. Take the example of an English native speaker learning French. French people are often surprised when they discover that an English native speaker has difficulty in hearing (let alone producing) the difference between words like French tu ‘you’ and tout ‘all’. The French vowel phonemes in these words, /y/ and /u/, seem alike to an English ear, sounding similar to the allophones of the English vowel phoneme /ui/ as in two. This effect can be represented as follows (using the symbol [ – ] to mean contrasts with):

French tu /ty/ – tout /tu/

English two /tuː/

On the other hand, French learners of English also have their problems. The English words sit and seat sound alike to French ears, the English vowel phonemes /I/ and /iː/ being heard as if they were allophones of French /i/ as in French site ‘site’:

English seat /siːt/ – sit /sIt/

French site /sit/

Another similar example is the contrast /Ʊ – uː/ as in the words pull and pool as compared with French /u/ in poule ‘hen’:

English pull /pƱl/ – pool /puːl/

French poule /pul/

Of course, we need not confine this to vowel sounds. Learners often have trouble with some of the consonants of English, for instance /θ/ as in mouth. German students of English have to learn to make a contrast between mouth and mouse. German has no /θ/, and German speakers are likely to interpret /θ/ as /s/ as in the final sound of Maus ‘mouse’ – this being what to a German seems closest to /θ/.

English mouth /maƱθ/ – mouse /maƱs/

German Maus /maƱs/

From the moment children start learning to talk they begin to recognise and appreciate those sound contrasts which are important for their own language; they learn to ignore those which are insignificant. We all interpret the sounds of language we hear in terms of the phonemes of our mother tongue and there are many rather surprising examples of this. For instance, the Japanese at first hear no difference between the contrasting phonemes /r/ and /l/ of English, e.g. royal – loyal; Greek learners cannot distinguish /s/ and /∫/ as in same and shame; Cantonese Chinese students of English may confuse /l/ not only with /r/ but also with /n/, so finding it difficult to hear the contrast between light, right and night. So non-natives must learn to interpret the sound system of English as heard by English native speakers and ignore the perceptions imposed by years of speaking and listening to their own language. Any English person learning a foreign language will have to undertake the same process in reverse.

Track 4

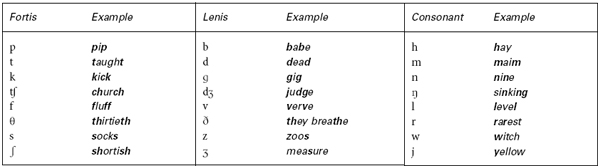

Track 4Certain of the English consonants function in pairs – being in most respects similar, but differing in the energy used in their production. For instance, /p/ and /b/ are articulated in the same way, except that /p/ is a strong voiceless articulation, termed fortis; whereas /b/ is a weak potentially voiced articulation, termed lenis. With other English consonants, there is no fortis/lenis opposition. Table A2.1 shows the English consonant phonemes.

Table A2.1The consonant system of English

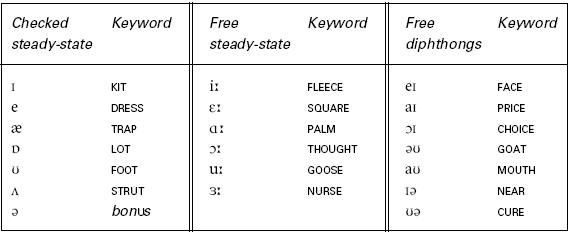

The vowels of English fall into three groups. We’ll classify these in very basic terms at the moment, but shall elaborate on this in Section B3, ‘Overview of the English Vowel System’. For steady-state/diphthong distinction, see pp. 69–70.

Checked steady-state vowels: these are short. They are represented by a single symbol, e.g. /I/.

Checked steady-state vowels: these are short. They are represented by a single symbol, e.g. /I/.

Free steady-state vowels: other things being equal, these are long. They are represented by a symbol plus a length mark i, e.g. /iː/.

Free steady-state vowels: other things being equal, these are long. They are represented by a symbol plus a length mark i, e.g. /iː/.

Free diphthongs: other things being equal, these are long. They have tongue and/or lip movement and are represented by two symbols, e.g. /eI/.

Free diphthongs: other things being equal, these are long. They have tongue and/or lip movement and are represented by two symbols, e.g. /eI/.

Note that all vowels may be shortened owing to prefortis clipping (see p. 58). The effect is most noticeable with free steady-state vowels and diphthongs.

In Table A2.2 we have provided keywords (adapted from Wells 1982) as a convenient way of referring to each of the English vowel phonemes. Keywords are shown in small capitals thus: KIT.

Table A2.2The vowels of English NRP

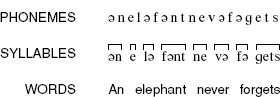

Figure A2.1Phoneme, syllable and word

The syllable is a unit difficult to define, though native speakers of a language generally have a good intuitive feeling for the concept, and are usually able to state how many syllables there are in a particular word. For instance, if native speakers of English are asked how many syllables there are in the word potato they usually have little doubt that there are three (even if for certain words, e.g. extract, they might find it difficult to say just where one syllable ends and another begins).

A syllable can be defined very loosely as a unit larger than the phoneme but smaller than the word. Phonemes can be regarded as the basic phonological elements. Above the phoneme, we can consider units larger in extent, namely the syllable and the word.

Typically, every syllable contains a vowel at its nucleus, and may have one or more consonants either side of this vowel at its margins. If we take the syllable cats as an example, the vowel acting as the nucleus is /æ/, and the consonants at the margins /k/ and /ts/. However, certain consonants are also able to act as the nuclear elements of syllables. In English, /n m l/ (and occasionally /ŋ/) can function in this way, as in bitten /'bIt /, rhythm /'rIð

/, rhythm /'rIð /, subtle /'sΛt

/, subtle /'sΛt /. Here the syllabic element is not formed by a vowel, but by one of the consonants /m n ŋ l/, which are in this case longer and more prominent than normal. Such consonants are termed syllabic consonants, and are shown by a little vertical mark [,] placed beneath the symbol concerned. In many cases, alternative pronunciations with /ə/ are also possible, e.g. /'rIðəm/. In certain types of English, such as General American, Scottish and West Country, /r/ can also be syllabic: hiker /'haIk

/. Here the syllabic element is not formed by a vowel, but by one of the consonants /m n ŋ l/, which are in this case longer and more prominent than normal. Such consonants are termed syllabic consonants, and are shown by a little vertical mark [,] placed beneath the symbol concerned. In many cases, alternative pronunciations with /ə/ are also possible, e.g. /'rIðəm/. In certain types of English, such as General American, Scottish and West Country, /r/ can also be syllabic: hiker /'haIk /.

/.

One of the most useful applications of phonetics is to provide transcription to indicate pronunciation. It is especially useful for languages like English (or French) which have inconsistent spellings. For instance, in English, the sound /iː/ can be represented as e (be), ea (dream), ee (seen), ie (believe), ei (receive), etc. See Section C6 for the same phenomenon in French.

7 (Answers on website)

Find a number of different spellings for (1) the vowel sounds of FACE, PRICE, THOUGHT and NURSE (in NRP /eI aI ɔː зː/) and (2) the consonant sounds /ʤ ∫ s k/.

Now try doing the same thing in reverse. See if you can find a number of different pronunciations for (1) the vowel letters o and a and (2) the consonant letters c and g.

Finally, a rather tougher question. One of the English checked vowel sounds is virtually always represented by the same single letter in spelling. Can you work out which sound it is? If you need more help, turn to p. 118.

We can distinguish between phonetic and phonemic transcription. A phonetic transcription can indicate minute details of the articulation of any particular sound by the use of differently shaped symbols, e.g. [?  ], or by adding little marks (known as diacritics) to a symbol, e.g.

], or by adding little marks (known as diacritics) to a symbol, e.g.  . In contrast, a phonemic transcription shows only the phoneme contrasts and does not tell us precisely what the realisations of the phoneme are. We can illustrate this difference by returning to our example of English /t/. Typically, a word-initial /t/ is realised with a little puff of air, an effect termed aspiration, which we indicate by [h], e.g. tea [thiː]. In many word-final contexts, as in eat this, we are more likely to have [t] with an accompanying glottal stop, symbolised thus: [iː?t ðIs]. In a phonemic transcription we would simply show both as /t/, since the replacement of one kind of /t/ by another does not result in a word with a different meaning (whereas replacing /t/ by /s/ would change tea into see).

. In contrast, a phonemic transcription shows only the phoneme contrasts and does not tell us precisely what the realisations of the phoneme are. We can illustrate this difference by returning to our example of English /t/. Typically, a word-initial /t/ is realised with a little puff of air, an effect termed aspiration, which we indicate by [h], e.g. tea [thiː]. In many word-final contexts, as in eat this, we are more likely to have [t] with an accompanying glottal stop, symbolised thus: [iː?t ðIs]. In a phonemic transcription we would simply show both as /t/, since the replacement of one kind of /t/ by another does not result in a word with a different meaning (whereas replacing /t/ by /s/ would change tea into see).

Both the phonetic and phonemic forms of transcription have their own specific uses. Phonemic transcription may at first sight appear less complex, but it is in reality a far more sophisticated system, since it requires from the reader a good knowledge of the language concerned; it eliminates superfluous detail and retains only the information essential to meaning. Even in a phonetic transcription, however, we generally show only a very small proportion of the phonetic variation that occurs, often only the most significant phonetic feature of a particular context. For instance, the difference in the pronunciation of the two r-sounds in retreat could be shown thus:  . Once we introduce a single phonetic symbol or diacritic then the whole transcription needs to be enclosed in square and not slant brackets.

. Once we introduce a single phonetic symbol or diacritic then the whole transcription needs to be enclosed in square and not slant brackets.

One way in which transcription can be of practical use is in distinguishing what are known as homophones and homographs. Both of these terms contain the element homo-, meaning ‘same’ in Greek; homophone means ‘same sound’ and homograph means ‘same writing’. You can think of homophones as sound-alikes and homographs as look-alikes (Carney 1997).

Homophones are words which sound the same but are written differently. Thanks to the irregularity of its spelling, there are countless examples in English, for instance bear – bare; meat – meet; some – sum; sent – scent. Homophones also exist in other languages (see p. 228 for examples in French). They’re one of the commonest causes of English spelling errors. And unlike other kinds of spelling error, they’re not normally detectable by computer spelling checkers. Can you say why?

8 (Answers on Website)

The following spelling errors would be impossible for most computer spelling checkers to deal with. Supply a suitable homophone to correct each of the sentences.

1 |

You’ll get a really accurate wait if you use these electronic scales. |

_______ |

2 |

Why don’t you join a quire if you like singing so much? |

_______ |

3 |

The people standing on the key saw Megan sail past in her yacht. |

_______ |

4 |

Harry simply guest, but luckily he got the right answer. |

_______ |

5 |

Passengers are requested to form an orderly cue at the bus stop. |

_______ |

6 |

The primary task of any doctor is to heel the sick. |

_______ |

7 |

For breakfast, many people choose to eat a serial with milk. |

_______ |

8 |

Janet tried extremely hard, but it was all in vein, I’m sad to say. |

_______ |

9 |

Why is the yoke of this egg such a peculiar shade of yellow? |

_______ |

10 |

The gross errors in the treasurer’s report are plane for all to see. |

_______ |

Note that homophones may vary from one English accent to another. To give one common example, in rhotic accents (see p. 96) like General American and Scottish, which pronounce spelt r in all contexts, word pairs which are homophones in NRP, like father and farther, do not sound alike. Similarly, in NRP which and witch are homo-phones, but not for speakers of Scottish English. For more information on types of accent variation see Sections C1–C4.

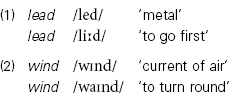

Homographs are words which are pronounced differently but spelt exactly the same. English has far fewer homographs than homophones. Here are two common pairs, with a phonemic transcription, and the meaning:

9 (Answers on Website)

Here is a set of homographs, each having two pronunciations and two different meanings. Fill in the appropriate meanings (one example has been done for you.) To help you, here are a number of brief definitions to choose from:

to decline; to find guilty; to provide accommodation; to run away; to scatter seed; to shut; kind of fish; building for living in; female pig; injury; liquid from the eye; low pitch; near; not legally acceptable; past tense of ‘to wind’; prisoner; rip up; rubbish; sandy wasteland; sick person

Transcription is not only used to represent words in isolation but can also be employed for whole stretches of speech. In all languages, the pronunciation of words in isolation is very different from the way they appear in connected speech (see ‘A Sample of Phonemic Transcription’, pp. 25–6). Phonemic transcription allows us to indicate these features with a degree of precision that is impossible to capture with traditional spelling. As such, it is an essential skill for phoneticians. In the next section of this chapter (after learning about some features of connected speech) you too will get to acquire this very useful ability.

1Also termed ‘alveolar ridge’.