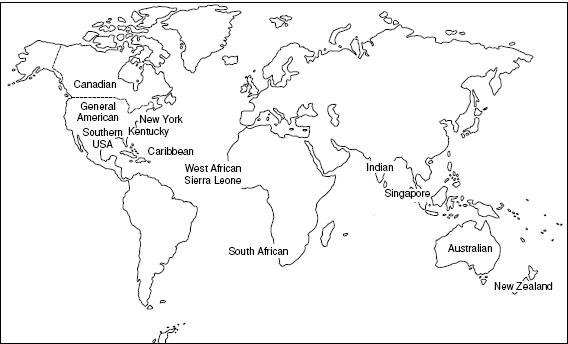

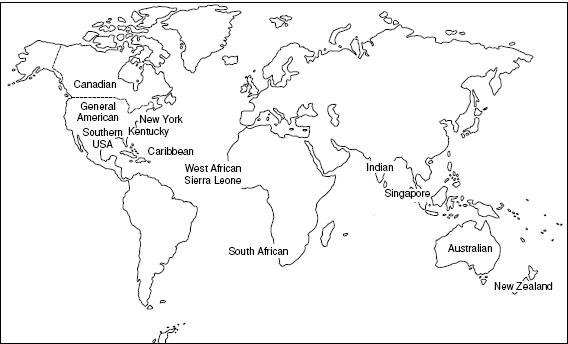

Figure C4.1Map showing locations of world accent varieties exemplified in this book

In this unit we shall examine four more types of North American English and three southern-hemisphere accents (Australia, New Zealand and South Africa). Second-language varieties are represented by Singapore and Indian English. Finally, Caribbean and Sierra Leone illustrate creole-influenced speech.

Track 53

Track 53Gary: Nacogdoches people look down their noses at Lufkin people – we think we’re – we think we’re – far superior to Lufkin –’cos they’re

Interviewer: do they make bad jokes about them

Gary: yeah – and they always beat us at football – we – we haven’t beat them since 1941 – no – well that’s not true – but – but – we our smashing football victory over Lufkin was in 1941 – when Lufkin was to be – Lufkin was – destined to be the state champs – state champions in their district – and Nacogdoches was not supposed to beat’em – and I was only six years old but Daddy – took me to the ball game I remember – and we beat Lufkin seven to six

Interviewer: all right

Gary: and I could remember – I wasn’t but six years old – and but I remember – after the game – Daddy going to town – took me to town – in the car – and we drove around the – square – around the – what’s now the library – used to be the post office – and Daddy was honking the horn – honking the horn – and I said Daddy, why are you honking the horn? – he said’cos we beat Lufkin – but we have not beat Lufkin at football many times since that time – we have beat them a few times – but – anyway – but Lufkin has some – some nice areas and Lufkin has a lot of industry

Interviewer: OK

Gary: that we do not have over here – it’s sort of a blue collar – it’s sort of a working-class – town – and Nacogdoches – we’ve always thought we were a little – little above Lufkin – of course actually we’re just jealous of Lufkin because they have all the good industries now – and our main – the best thing Nacogdoches has going for it – is the college – is the university – that’s our main source of – income

The English of the southern United States sounds quite different from that of the north of the country. Traditionally, the southern states have always been regarded as the poorer, more backward parts of the USA but they have been catching up rapidly since the mid-twentieth century. But perhaps because of the long-standing economic differences, northerners have tended to look down on the accents of the south, and stereotype them as sounding amusing and uneducated. As a result, some southerners try to modify their speech and make it sound closer to the language of their northern neighbours.

Gary is a lawyer with an educated, but quite distinctly Texan, accent. Nacogdoches /nækə'dəƱt∫əz/ and Lufkin are two towns, situated about 30 kilometres’ distance from each other in eastern Texas in the southern USA. As Gary explains, there has always been a friendly rivalry between the neighbouring communities.

Unlike General American (GA), some southern USA English is variably non-rhotic. Notice how Gary deletes /r/ in  horn, years and remember, but pronounces it in far superior. There is t-voicing (

horn, years and remember, but pronounces it in far superior. There is t-voicing ( forty, beat’em, little). Unlike Kathy (see Section C1), Gary, a southerner, and from the older generation, uses /M/ in wh-words (

forty, beat’em, little). Unlike Kathy (see Section C1), Gary, a southerner, and from the older generation, uses /M/ in wh-words ( what’s). A salient feature is the replacement of fricative /z / by a stop /d / preceding nasal /n / in

what’s). A salient feature is the replacement of fricative /z / by a stop /d / preceding nasal /n / in  wasn’t [wad

wasn’t [wad t].

t].

Much of what we have said about General American also applies to southern USA English. But southern USA English has several distinctive characteristics – notably in the vowel system. For instance, the price vowel often lacks any glide, sounding like a long vowel [aː] ( times, I, library). Another noticeable feature is the phenomenon called ‘breaking’, which involves inserting [ə] between a vowel and the following /r/ or /l/. Notice, for instance, how the vowels in

times, I, library). Another noticeable feature is the phenomenon called ‘breaking’, which involves inserting [ə] between a vowel and the following /r/ or /l/. Notice, for instance, how the vowels in  square, ball, old become [εiə, ɔːə, əƱə].

square, ball, old become [εiə, ɔːə, əƱə].

The absence of contracted forms with not is also characteristic of southern speech ( ‘Nacogdoches was not supposed to beat’em’, ‘that we do not have over here’).

‘Nacogdoches was not supposed to beat’em’, ‘that we do not have over here’).

One of the most striking things about southern USA English is its rhythm and intonation. It is often described as ‘drawling’, implying that it sounds slow and drawn out to other Americans. Intonation tunes also appear more extended than in GA. Notice how high-pitched the syllable  Luf-is in ‘but Lufkin has some …’, ‘Lufkin has a lot of industry’).

Luf-is in ‘but Lufkin has some …’, ‘Lufkin has a lot of industry’).

Track 54

Track 54Bill: well I’m – right now we’re living in Louisville – Louisville Kentucky, which – we don’t have accents in Louisville any more but – that – I went – I was raised about two hours east of here in the – Appalachian Mountains in Irvine Kentucky – which is a town of thirty-five hundred – and now if you want to hear accents we just call Jobie – he lives there in Irvine – and I guess that – you get a sampling of what – what the dialect would be up that way – but – usually when I call home I really get my old – accent back in a hurry – and then when I call California I lose it so – but – I’ve been trying to get Jacob to come up there and spend a couple of days on the farm and relax a little bit – but – he’s got another two thousand miles to go – here you’re going to have to go up there – Mike and Barb – Mom’s sister has a – farm up there – they have like – seven horses – and it’s up in – near Red River Gorge – which is just one of the prettiest parts of the state – and we go horseback riding up there – and when you come we’re going to have to hop on one of those things – I guess you ride horses don’t you – but – it’s beautiful up there and you put – especially here in two weeks when the leaves will have turned – it’s going to be nice

Bill would also regard himself as a middle-class speaker but is proud of his country origins. Kentucky is geographically a South Midland state but, at least in its rural forms, has many affinities with the south. Nevertheless, one exceptional feature (heard clearly in Bill’s speech) is consistent rhoticism ( farm, horseback). Final -ing is pronounced as /In/ rather than /Iŋ/ (

farm, horseback). Final -ing is pronounced as /In/ rather than /Iŋ/ ( riding). The FLEECE, GOOSE, FACE and GOAT vowels are extended (

riding). The FLEECE, GOOSE, FACE and GOAT vowels are extended ( leaves, lose, raised, home), whereas the PRICE vowel is steady-state (cf. Texas) (

leaves, lose, raised, home), whereas the PRICE vowel is steady-state (cf. Texas) ( dialect, riding, miles). A feature characteristic of many southern American varieties is the neutralisation of the KIT and DRESS vowels before /n/, KIT being used for both (

dialect, riding, miles). A feature characteristic of many southern American varieties is the neutralisation of the KIT and DRESS vowels before /n/, KIT being used for both ( spend [spInd]). The final syllable in accents shows no vowel reduction. Bill also has extended intonation patterns similar in some ways to southern varieties (

spend [spInd]). The final syllable in accents shows no vowel reduction. Bill also has extended intonation patterns similar in some ways to southern varieties ( ‘which is a town of thirty five hundred’, ‘and spend a couple of days on the farm and relax a little bit’).

‘which is a town of thirty five hundred’, ‘and spend a couple of days on the farm and relax a little bit’).

Track 55

Track 55Lorraine: right because I didn’t pay enough all along – but the – I work a whole lot harder than I ever did – he might not get work in till three o’clock four o’clock sometimes five o’clock – comes in – so I’ll stay and I’ll work – it’s not unusual for me to work till eight or nine o’clock – I may sit around for three hours four hours during the day – sometimes I leave – usually I (?)

Tony: do they pay you on a job basis –

Lorraine: they pay – they pay me for as many hours as I work

Tony: OK

Lorraine: in the beginning he paid me whether I was working or not – and then as my relationship got a little better with him – I felt that – not that it really wasn’t fair – but – I’m using his telephone – like when I call Connecticut I charge that on my own bill – you know I charge it to my home – but I use his phone for local calls – I use his photocopy machine – he’s not exactly the best payer but he pays – and he lets me use his facilities – and so I’m there answering you know his phone and what’s good is – I may need a week off – or – Monday for example I normally would have worked but now I made an appointment – and I have an appointment in the afternoon – so if I had a regular job – I couldn’t work for anyone else – because my schedule wouldn’t allow it – I miss having a steady pay check every week – I miss that’cos at least – whether it’s two hundred or it’s eight hundred dollars it’s steady and you know what you have coming in – so I miss that – I don’t like all the book-keeping I have to do now – I hate doing billing – I don’t like doing that stuff – no – I just went for another freelance job – right over here – they make machinery that folds – things – or packages – products – like if you buy a new shirt – it’s folded into that plastic bag – it’s the ugliest piece of equipment – they have the ugliest work – so no matter what you do – it’s nicer than what they had before and they like it …

Even though it may no longer be the biggest city in the world, New York is still enormous. Over eight million people live in the city itself, while the metropolitan area has a population of approximately twenty million. New York is famous for its cosmopolitan atmosphere, and for being home to a bubbling mixture of races, religions and languages. Many New Yorkers don’t even have English as their first language (Spanish is widely spoken, and you also can hear languages such as Chinese, Russian, Italian, French and Yiddish, to name just a few, at any street corner). Nevertheless, the city’s brand of English is famous all over America, and thanks partly to artists like the Marx Brothers and Woody Allen, and more recently politician Rudy Giuliani, the New York accent is instantly recognisable (at least in its stereotypical form) throughout the USA. For whatever reason, the accent has a poor image for Americans, being held in low esteem even by New Yorkers themselves – as is testified by the large number of courses available through the Internet offering New Yorkers the chance to ‘improve their accent’. Our speaker, Lorraine, is a white university graduate, who lives in a suburb on Long Island. She works free-lance for several New York companies in the field of graphic design. While she has a middle-class occupation and life style, nevertheless she speaks with an unmistakably New York accent, although lacking some of the now stigmatised basilectal accent features.

Unlike GA and most other American accents, a salient feature of New York English is its non-rhoticism. This was formerly heard from all social classes, but for a long time this situation has been changing, and nowadays r-dropping has become a strongly stigmatised feature. Nevertheless, mainstream New York speech is notable for variable non-rhoticity, and this is also the source of much linguistic insecurity. Lorraine is no exception, and is indeed variably non-rhotic; in  here, better, fair, payer, morning /r/ is deleted, yet it is pronounced in

here, better, fair, payer, morning /r/ is deleted, yet it is pronounced in  work, charge, shirt. New York speech is often mocked for instances of intrusive-r (see p. 124), but Lorraine produces no examples in this sample. If /r/ is absent, an off-glide is heard with THOUGHT, SQUARE and NURSE, e.g.

work, charge, shirt. New York speech is often mocked for instances of intrusive-r (see p. 124), but Lorraine produces no examples in this sample. If /r/ is absent, an off-glide is heard with THOUGHT, SQUARE and NURSE, e.g.  morning [mɔənIŋf],

morning [mɔənIŋf],  fair [feə], bird [bзId]. In fact, many New Yorkers who are in general non-rhotic seem regularly to use /r/ in NURSE words. This might well have its origins in an attempt to avoid the old-fashioned highly stigmatised pronunciation [bзId] (often misrepresented as ‘boid’) which was a feature of pre-1950 New York speech; Groucho Marx made this vowel almost his trademark.

fair [feə], bird [bзId]. In fact, many New Yorkers who are in general non-rhotic seem regularly to use /r/ in NURSE words. This might well have its origins in an attempt to avoid the old-fashioned highly stigmatised pronunciation [bзId] (often misrepresented as ‘boid’) which was a feature of pre-1950 New York speech; Groucho Marx made this vowel almost his trademark.

In common with all United States accents, there is no h-dropping ( whole, having), and like the vast majority of present-day Americans, Lorraine has no /M – W/ opposition;

whole, having), and like the vast majority of present-day Americans, Lorraine has no /M – W/ opposition;  whether and

whether and  work both start with /w/. New York /l/ is often very dark (velarised) even pre-vocalically (

work both start with /w/. New York /l/ is often very dark (velarised) even pre-vocalically ( along, lets, don’t like all, ugliest); note that both the allophones of /l/ in

along, lets, don’t like all, ugliest); note that both the allophones of /l/ in  local sound rather similar.

local sound rather similar.

Like GA, intervocalic /t/ almost invariably has t-voicing ( better, but I, facilities, matter). New York is notorious for the prevalence of th-stopping. The fricatives /θ ð/ tend to be produced as dental stop articulations [

better, but I, facilities, matter). New York is notorious for the prevalence of th-stopping. The fricatives /θ ð/ tend to be produced as dental stop articulations [

], and since the plosives /t d/ may also be dental stops, this results in confusion of /θ – t, ð – d/. Because th-stopping is heavily stigmatised, most New Yorkers attempt to remove this feature from their speech. So it is not surprising that Lorraine varies, producing fricatives for the most part, but showing th-stopping in, for instance,

], and since the plosives /t d/ may also be dental stops, this results in confusion of /θ – t, ð – d/. Because th-stopping is heavily stigmatised, most New Yorkers attempt to remove this feature from their speech. So it is not surprising that Lorraine varies, producing fricatives for the most part, but showing th-stopping in, for instance,  three, they pay they pay, felt that – not that).

three, they pay they pay, felt that – not that).

Like the rest of America, New Yorkers use the TRAP vowel in BATH words ( freelance, asking, answering, afternoon). TRAP is often very close and a salient basilectal feature is a centring off-glide [εə] or even [Iə]. Lorraine’s TRAP vowel is indeed relatively close, but it lacks the stigmatised glide (

freelance, asking, answering, afternoon). TRAP is often very close and a salient basilectal feature is a centring off-glide [εə] or even [Iə]. Lorraine’s TRAP vowel is indeed relatively close, but it lacks the stigmatised glide ( freelance, bag, packages). A characteristic feature of New York speech is that the THOUGHT vowel is used for both THOUGHT (e.g.

freelance, bag, packages). A characteristic feature of New York speech is that the THOUGHT vowel is used for both THOUGHT (e.g.  morning, four, call) and for most words spelt o preceding /f θ s g ŋ/ (e.g.

morning, four, call) and for most words spelt o preceding /f θ s g ŋ/ (e.g.  off, along). THOUGHT is realised much closer than in GA, and can sound rather similar to the equivalent sound in British NRP. Like TRAP, it sometimes has a centring glide [ɔə]. This means that in basilectal New York accents, words like law, lore and lost all have the same vowel. The PALM vowel (

off, along). THOUGHT is realised much closer than in GA, and can sound rather similar to the equivalent sound in British NRP. Like TRAP, it sometimes has a centring glide [ɔə]. This means that in basilectal New York accents, words like law, lore and lost all have the same vowel. The PALM vowel ( charge, o’clock, job) is much more back and often somewhat closer than in GA – similar, in fact, to GA THOUGHT so making New York darn sound like GA dawn. Two well-known salient New York features which Lorraine regularly produces are a PRICE diphthong with a back starting point (

charge, o’clock, job) is much more back and often somewhat closer than in GA – similar, in fact, to GA THOUGHT so making New York darn sound like GA dawn. Two well-known salient New York features which Lorraine regularly produces are a PRICE diphthong with a back starting point ( nine, buy), and MOUTH with a very fronted starting point (

nine, buy), and MOUTH with a very fronted starting point ( allow, now).

allow, now).

In terms of suprasegmental features, Lorraine has characteristic New York intonation. She has a somewhat extended pitch range as compared with GA, with numerous rise-falls, and conspicuous rising and high falling tones (a mixture often popularly stigmatised as the ‘New York whine’), e.g.  because I didn’t pay enough all along; work a whole lot harder than I ever did; it’s not unusual for me to work till eight or nine o’clock. Along with her somewhat velarised voice quality combined with nasalisation, these features are typical of a New York accent.

because I didn’t pay enough all along; work a whole lot harder than I ever did; it’s not unusual for me to work till eight or nine o’clock. Along with her somewhat velarised voice quality combined with nasalisation, these features are typical of a New York accent.

Track 56

Track 56Anne: the set-up of the university is very different than what I found here – I mean – there’s – all the buildings are in one location – and there’s probably – well at least fifty different buildings – all – centred right there – I mean and then there’s the residences – so – first-year students usually stay in residences – and then once you’ve met a couple of friends in second year and – up until fourth year you usually live in a house – with a couple of your friends right around – the – all the buildings of – of campus – we like to call it the student ghetto – so I mean we still only have a five-minute walk to class or so – so it’s very different – than here – because here you find you only have to bike from building to building – and from your house to – and everything is so much more spread out here – …

It’s the most beautiful place – like in Canada that I’ve really ever been to – it is so pretty – it’s along the Ottawa river – and so I mean – the whole town is on the river – so there’s beaches everywhere – and it’s a very outdoorsy outdoorsy – kind of – nature town – and – I mean if you enjoy skiing – like cross-country skiing is very big there – and just all kinds of water sports like – canoeing – or fishing – even biking – just anything outdoors – you know you’ll find it in my town – it’s very active – outdoorsy town – yeah

Canada has a population of 29 million people, but a sizeable minority of these are French speakers while many recent immigrants don’t have English as their mother tongue. Nevertheless, this still leaves perhaps as many as 18 million English native speakers. The overwhelming influence on Canadian pronunciation (uniquely amongst the major countries of the former British Empire) is USA English, but Scottish and Irish influences are also claimed. In fact, Canadian English, although recognisably a distinct variety, is much closer to General American than are many regional varieties of the USA itself. Within Canada, there is considerable variation on the Atlantic seaboard, notably the ‘Newfie’ speech of Newfoundland.

The speaker, Anne, grew up in a rural area (the Ottawa Valley) 200 kilometres west of Ottawa and was an exchange student in a European university at the time of recording. Like most American English, Anne’s Canadian accent is h-pronouncing ( house), rhotic (

house), rhotic ( river, water, fourth) and has t-voicing (

river, water, fourth) and has t-voicing ( Ottawa, water, beautiful). Yod-dropping is variable, but generally less prevalent in Canada than in the USA; Anne retains /j/ in

Ottawa, water, beautiful). Yod-dropping is variable, but generally less prevalent in Canada than in the USA; Anne retains /j/ in  student. Her realisation of /l/ tends to be dark in all contexts (

student. Her realisation of /l/ tends to be dark in all contexts ( along).

along).

BATH words have the TRAP vowel ( class). Anne’s front vowels, KIT, DRESS and TRAP, are all rather open (

class). Anne’s front vowels, KIT, DRESS and TRAP, are all rather open ( river, residence, Canada). The THOUGHT and PALM vowels are merged, both sounding like palm, e.g.

river, residence, Canada). The THOUGHT and PALM vowels are merged, both sounding like palm, e.g.  probably, walk. Possibly the most salient feature of Canadian English is the centralised [ə]-like nature of the starting-points of the diphthongs PRICE [əI] and MOUTH [əƱ] when they precede fortis consonants, e.g.

probably, walk. Possibly the most salient feature of Canadian English is the centralised [ə]-like nature of the starting-points of the diphthongs PRICE [əI] and MOUTH [əƱ] when they precede fortis consonants, e.g.  right, bike, like, house, out; compare the non-centralised diphthongs in

right, bike, like, house, out; compare the non-centralised diphthongs in  five, find, found, town. Note the upspeak terminal rise intonation patterns in

five, find, found, town. Note the upspeak terminal rise intonation patterns in  of campus; walk to class or so; just anything outdoors. See pp. 274 – 8; also pp. 192, 193 and 208.

of campus; walk to class or so; just anything outdoors. See pp. 274 – 8; also pp. 192, 193 and 208.

Track 57

Track 57Helen: university is a lot different from school – do you want to know about that – it’s a little bit just – the holidays – because – university – now have holidays in semesters – whereas the schools still have them in terms – and schools are really trying to get their holidays in semesters – because that’s what you work in – and it seems strange having term holidays when you’re working in semesters – but at university we have – three – well it all depends on when your exams finish – there’s – you have two weeks of holidays – but – most exams – you have three weeks of exams – and then – say two weeks of holidays – but – not many people have exams – towards the end of those three weeks – most people will be finished with their exams within the first – what – at least two weeks – so you’ll have probably at least three weeks’ holiday – and you can go home as soon as you’ve finished your exams – and so – well I – I had over – I had three and a half weeks’ holiday – this year – that was in the middle and – you really need the break – and we also have mid-semester holidays – which – this year – in the semester that I had the first semester before I came over here – it wasn’t – it wasn’t in the middle of semester – it was – I suppose they shouldn’t be really called mid-semester because it was just a week off – and the week was two weeks before we started swot-vac

swot-vac: Australian informal term for a non-teaching period (vacation) which allows students to work intensively (colloquial ‘to swot’) for their examinations.

Australia, with a present-day population of over 20 million and growing, appears set to become one of the chief standard forms of English of the future. Until recently, most of its population came from the British Isles, with a majority from southern England, and this is reflected in the nature of Australian speech today. Australian is a relatively young variety of English, and there are as yet no distinct regional accents in Australia; all over this vast country, people sound surprisingly similar. However, as mentioned in Section A1, there are distinct social differences. This speaker, Helen, is a university student, and speaks what would be classified as ‘General Australian’ English (i.e. neither ‘Broad’ nor ‘Cultivated’, see pp. 7–9).

Australian English is non-rhotic ( working, semesters). Broad accents have some h-dropping, but this is much less common than in England, and there is no trace of this in Helen’s speech (

working, semesters). Broad accents have some h-dropping, but this is much less common than in England, and there is no trace of this in Helen’s speech ( holidays, home). Helen has regular medial t-voicing similar to that found in much General American (

holidays, home). Helen has regular medial t-voicing similar to that found in much General American ( university, started). Her /l/ is noticeably dark. Systemically, the Australian vowel inventory is identical to that of NRP. Lexical variation is a feature of certain BATH words, where the TRAP vowel rather than PALM is often found in words like dance, example, i.e. before nasal plus obstruent coda clusters. When preceding fricatives, e.g. path, grasp,

university, started). Her /l/ is noticeably dark. Systemically, the Australian vowel inventory is identical to that of NRP. Lexical variation is a feature of certain BATH words, where the TRAP vowel rather than PALM is often found in words like dance, example, i.e. before nasal plus obstruent coda clusters. When preceding fricatives, e.g. path, grasp,  half, PALM is much more frequent.

half, PALM is much more frequent.

In terms of realisational variation, the front vowels dress and TRAP are close ( semesters, exams). There is diphthong shift with wide glide realisations in FACE and GOAT (

semesters, exams). There is diphthong shift with wide glide realisations in FACE and GOAT ( break, go home). The PALM vowel (

break, go home). The PALM vowel ( started) is very fronted [aː] while NURSE is close and fronted, sometimes with rounding [øː] (

started) is very fronted [aː] while NURSE is close and fronted, sometimes with rounding [øː] ( work).

work).

Helen’s speech provides some good examples of one very well-known feature of Australian English, namely ‘upspeak’ terminal rise intonation (in fact another term occasionally used is ‘Australian question intonation’). See pp. 274 – 8. Note the terminal rises in  so you’ll have probably at least three weeks’ holiday – and you can go home as soon as you’ve finished your exams.

so you’ll have probably at least three weeks’ holiday – and you can go home as soon as you’ve finished your exams.

Track 58

Track 58Simon: Thursday night we decided to go down to the pub – and that made me feel quite good because I really wanted to have a beer – and so – we went down there and we had a beer – and then on the way home – we were there for a couple of hours – we got back to the flat – and – we saw that the back door was open – and – some people thought that maybe – there was – other flatmate had got home – forgotten to close it – but I had this sinking feeling in my stomach – that maybe – maybe that something dodgy was going on – because the lights were on and the door was open – and I had this bit of a sick feeling in my stomach – and so as we walked in the door – we saw that all the cupboards – the food cupboards – were all opened – and that’s when we knew that something wasn’t right – and I thought to myself – oh no – this is very bad – and so we walked through the house – we came down to – Rachel and I came down to her room – and everything had been turned out on to her bed – the desk was trashed – some money was stolen – you know – things were all rifled through – and – it was a very very bad scene – it’s not – it makes – you know – it makes you feel really bad when you see that your stuff’s been gone through – and – it turns out that – one of the flatmate’s cars had been stolen as well – to carry all the stuff – and – one of the other flatmate’s – all his guitars – heaps of – thousands and thousands of dollars worth of stuff was stolen – everybody felt really – unhappy about the whole situation I have to say – and – the police came around – and we told them what had happened – but nobody was insured – and so everybody felt a bit sick – and I felt really sorry for everybody – even though I didn’t have that much stuff here – and – the next day – the crime scene investigator guy came but – they’re not very confident of catching anyone – so – I feel a bit let down by society in – in this respect – that we don’t live in a safe place – and my – and my faith in humanity has been – severely knocked –

Most of New Zealand’s four million people speak English as their first language – even though there are still a significant number of Maoris who are bilingual. Located geographically over two thousand kilometres from Australia, New Zealand nevertheless shares many cultural ties with its closest neighbour, so it isn’t surprising that we find similarities between these two antipodean varieties. Our speaker, Simon, is a post-graduate student at Canterbury University in the South Island and speaks an educated variety of New Zealand English. His speech, like that of most New Zealanders (all except those from the extreme southern portion of South Island), is non-rhotic ( hours, insured).

hours, insured).

Although New Zealand English resembles Australian English in many ways, there are some interesting differences, and the pronunciation of the kit vowel is a sure-fire way of picking out a New Zealander. KIT is noticeably central for Simon as for most New Zealanders, and is levelled with /ə/ ( sick, live). DRESS and TRAP are both even closer than in Australian English (

sick, live). DRESS and TRAP are both even closer than in Australian English ( desk – sounding very like disk in most other varieties – everybody; flat, bad). The SQUARE vowel is often very similar to English NRP near (there are no instances of SQUARE on this recording).

desk – sounding very like disk in most other varieties – everybody; flat, bad). The SQUARE vowel is often very similar to English NRP near (there are no instances of SQUARE on this recording).

Other features are indeed very like Australian. Simon’s NURSE vowel is front and rounded ( Thursday, turned) and PALM is extremely front (

Thursday, turned) and PALM is extremely front ( cars, guitars). The NEAR vowel is often disyllabic (

cars, guitars). The NEAR vowel is often disyllabic ( here, beer [hiːə biːə]). A feature of the consonant system is a noticeably dark l (

here, beer [hiːə biːə]). A feature of the consonant system is a noticeably dark l ( police, feeling). There is frequent medial t-voicing (

police, feeling). There is frequent medial t-voicing ( investigator). As with Australian speakers, rising terminal upspeak intonation patterns frequently occur (

investigator). As with Australian speakers, rising terminal upspeak intonation patterns frequently occur ( … to carry all the stuff, … were all opened). Simon’s mesolectal variety lacks the extended diphthong shift forms of FACE and GOAT found in broader New Zealand accents.

… to carry all the stuff, … were all opened). Simon’s mesolectal variety lacks the extended diphthong shift forms of FACE and GOAT found in broader New Zealand accents.

Track 59

Track 59Nicole: it depends – English schools in South Africa are far more formal – especially the school I went to – which is the Pretoria High School for Girls – an only girls’ school – an Anglican school at that – so it was quite formal – and – I didn’t really enjoy my time there – the Afrikaans school was much more fun – not as posh and la-di-da as the – as the – English school – but – the people were much warmer – they loved the idea of having an English person wanting to learn their language – that was a whole new idea to them – since they were usually the ones having to adapt – and there was – there was lots of fun … Bobotie is very – OK it’s actually a mince dish – with raisins and cloves in it – and – some special kinds of leaves – what are they called again – I can’t remember what the leaves are called – funny name – bit of an exotic name – and it’s – it’s eaten with rice – which you – that yellow kind of rice also with raisins – and you basically bake it in the oven – so it’s a very spicy meat dish – South Africans eat a lot of meat by the way – a lot of meat – they’re real carnivores – and they also like eating potatoes and rice together – so a typical South African dinner – would be meat potatoes rice and a vegetable – something else that’s – is eaten in South Africa very often – especially among the black people – is what they call putupap or mealiepap – it’s basically – crushed – crushed corn – and that’s really ground into a into a sort of a powder – and then cooked up – and then you get this type of white porridgy substance – and that’s very filling – although not very nutritious – so – many poorer black people eat that – very often – but – are malnourished because of it – so – those things are eaten quite often – and what the black people also love eating – is – you know the intestines and brains and eyes and those things – those really are delicacies among the amongst the black people so

Interviewer: but you don’t eat them

Nicole: no – I couldn’t – I couldn’t really

Some people may still be surprised to hear that mother-tongue English speakers are very much in the minority in South Africa, numbering no more than about three and a half million in total. The English of South Africa is much influenced by Afrikaans – a language similar to Dutch, with perhaps as many as six million speakers. It has been said that South African English ranges all the way from broad accents strongly influenced by Afrikaans to upper-class speech which sounds very similar to British traditional RP (Crystal 2010: 40). In the new South Africa many black South Africans who speak African languages, such as Zulu, Xhosa and Sotho, now speak English as a second language.

Our speaker, Nicole, is a student who had spent one year at an Afrikaans-speaking school, but had the rest of her schooling from English-speaking institutions. Although Nicole’s speech is very recognisably South African, hers is a middle-class mesolectal variety lacking many of the potentially stigmatised features (such as voiced /h/ and unaspirated /p t k /).

There is no h-dropping ( high, having) (but broad South African accents have voiced /h/) and the accent is non-rhotic (

high, having) (but broad South African accents have voiced /h/) and the accent is non-rhotic ( are far more formal). The distribution of clear vs. dark l is as in NRP and many other varieties, but dark l has a hollow pharyngealised quality (

are far more formal). The distribution of clear vs. dark l is as in NRP and many other varieties, but dark l has a hollow pharyngealised quality ( else, school, people). /t / is strongly affricated (

else, school, people). /t / is strongly affricated ( wanting, eating, a lot of), perhaps a slight over-compensation for the lack of aspiration in much South African English. Nicole has very little glottalisation (

wanting, eating, a lot of), perhaps a slight over-compensation for the lack of aspiration in much South African English. Nicole has very little glottalisation ( went to, it was, much).

went to, it was, much).

DRESS and TRAP are close ( together, went, black, adapt). In certain words, the KIT vowel is central resembling [ə] (

together, went, black, adapt). In certain words, the KIT vowel is central resembling [ə] ( dinner, mince, cf. New Zealand). STRUT is relatively front (

dinner, mince, cf. New Zealand). STRUT is relatively front ( much, fun). LOT is open and unrounded (

much, fun). LOT is open and unrounded ( wanting, not). The happY vowel is said with a close short FLEECE vowel (

wanting, not). The happY vowel is said with a close short FLEECE vowel ( really, funny, basically). The PALM vowel is very back (e.g.

really, funny, basically). The PALM vowel is very back (e.g.  far, carnivores). PRICE and MOUTH have relatively narrow glides (

far, carnivores). PRICE and MOUTH have relatively narrow glides ( time, kinds, rice, ground, south, powder). SQUARE is very close (

time, kinds, rice, ground, south, powder). SQUARE is very close ( their). The weak form of the is consistently /ðə/ whether it occurs before a vowel or a consonant (

their). The weak form of the is consistently /ðə/ whether it occurs before a vowel or a consonant ( the idea, the English, the oven). The PALM vowel is used in BATH words (

the idea, the English, the oven). The PALM vowel is used in BATH words ( can’t).

can’t).

Track 60

Track 60Rajiv: and of course the politics – they keep on going on with all stupid things I think – I don’t know why – but – that is the reason I think because the rest I don’t understand because – India and Pakistan used to be – they were in the beginning like – let’s say – before the partition – were in a – yeah – it was a big country – and half of them were in India and the other half was in Pakistan – I don’t know how come the friction came but – why we have this friction I think maybe – both countries want to prove that I’m better than another – that is the reason I think – but the rest yeah – if you talk to the Pakistani like – Wasim the other guy – if you talk sometime about the politics (?) – why we have problem – then I say because of the politics – the politician they – they look for their own interest – and he say – absolutely the same thing – the politics – the politician they look for their own interest – that they – just – this way they keep – they keep their own their seats – if you ask the people – maybe people don’t allow – they don’t want any – this kind of a nonsense – because life itself is pretty hard

In terms of numbers, Indian English is without doubt a major world variety; estimates vary, but it could have as many as thirty million speakers. ‘Indian English’ is used loosely to include the English spoken in all the Southern Asian area, i.e. that part of Asia which includes India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. The chief languages, including Hindi, Urdu, Bengali and Punjabi, are all spoken by many millions of people. Because there are so many different languages all over Southern Asia, English is recognised as an official medium which all educated people can use. Consequently, in India, as in all the countries of Southern Asia, English means essentially second-language English. Our speaker, Rajiv, comes from Delhi and is a Hindi speaker but from his schooldays onwards has been speaking English on a day-to-day basis.

One of the most striking things about much Indian English, and this is true of Rajiv’s speech, is that many consonants are retroflex (see Section A5); this is true of /t d s z l n r/ ( better, hard, pretty). Rajiv regularly has th-stopping whereby the dental fricatives /θ ð/ are replaced by /t d/ (

better, hard, pretty). Rajiv regularly has th-stopping whereby the dental fricatives /θ ð/ are replaced by /t d/ ( think, both, that, they). The consonants /v/ and /w/ are not consistently distinguished (

think, both, that, they). The consonants /v/ and /w/ are not consistently distinguished ( why, we), or a compromise (a labio-dental approximant) is used for both. As with most Indians, Rajiv’s English is rhotic (

why, we), or a compromise (a labio-dental approximant) is used for both. As with most Indians, Rajiv’s English is rhotic ( hard, partition); initial and medial /r/ are generally strong taps (

hard, partition); initial and medial /r/ are generally strong taps ( reason, rest). /p t k / are unaspirated (

reason, rest). /p t k / are unaspirated ( politics, talk, keep) and /b d g/ are voiced throughout (

politics, talk, keep) and /b d g/ are voiced throughout ( because, guy, big).

because, guy, big).

Most types of Indian English use the vowels of the local Indian language and these will sound quite unlike those of native English. Note also that some Indian words are said differently in English from the way they are pronounced in India itself. For instance, the name Gandhi has a long PALM vowel in Indian languages but a short vowel in British English.

Indian English is notable for its syllable-timed rhythm, a feature it shares with many Indian languages ( ‘life itself is pretty hard’). In many Indian languages stress does not appear to fall on any particular syllable (cf. French, pp. 131, 228), resulting in unexpected stress patterns in Indian English (

‘life itself is pretty hard’). In many Indian languages stress does not appear to fall on any particular syllable (cf. French, pp. 131, 228), resulting in unexpected stress patterns in Indian English ( beginning). These effects can cause intelligibility problems for non-Indians trying to understand these Indian varieties of English.

beginning). These effects can cause intelligibility problems for non-Indians trying to understand these Indian varieties of English.

Track 61

Track 61Ben: everybody has to go through national service in Singapore – I mean not everybody – every – every male citizen has – have to go through national service in Singapore – from – I think after sixteen you can – you can enlist – but you have to do it from within two to two and a h- – you have to do it – you have to – you have to serve – in the army – I mean – you have to join the national service for two to two and a half years – so you have some – you’re just trained as a soldier and – I think basic training – they have lots of accidents and – dangerous stuff like live firing – live explosives and – yeah – and – lots of military training – so I think – I think the rate of – I think this is – I’ve seen – I’ve – of I’ve heard stories that people get killed – and they’re reading – I’m not really sure if it’s real but – maybe it’s a story to scare all of us – but I’ve seen – people – I’ve think I’ve seen – people – one person commit suicide before – because uh – it’s quite – pressurising in – in the army – of course – I mean – I mean the – your – I mean most people can take it but some people – are not suited to do military service – but they’re still forced to because it’s – it’s by law that you have to do it – so – they can’t really – probably can’t take the pressure and kill themselves – so – yeah I’ve seen – once – someone just jumped down a building – and – there was a huge commotion – everyone surrounding him – and they had uh – they had to get a helicopter from somewhere – and carried him off to a stretcher – I don’t know if he’s still alive – but I mean he jumped from the fifth floor I think – so yeah

Interviewer: not a good thing

Ben: yeah and – yeah we – we didn’t like – we do – grenade throwing – live firing – everything – and uh – we do – obstacle courses where – they actually fire live rounds two metres from the ground level – but I mean – unless we – unless you jump up you get hit – so for that obstacle course we all just on our – on our hands there – I mean we are crawling on the ground – through barbed wire and everything and – yeah

Singapore is a truly multicultural country. Most of its inhabitants are of Chinese origin, but a variety of languages are spoken by the two and a half million people crowded onto this small island. English is only one of four official languages, but it has a special position since most Singapore children go to English-language schools. They understand English well and speak their own variety – sometimes called ‘Singlish’ – fluently. Our speaker, Ben, is typical of many educated Singapore people. Although he is fluent in two types of Chinese, he regularly speaks English both for his work and in conversation with his friends. He can move with ease between more formal English for work to something much closer to Singlish when relaxing with friends.

Ben has no h-dropping ( has to, helicopter) and his speech is non-rhotic (

has to, helicopter) and his speech is non-rhotic ( heard, barbed wire, person). The dental fricative /θ/ is variably replaced by /t / (

heard, barbed wire, person). The dental fricative /θ/ is variably replaced by /t / ( through, throwing). Final dark l is regularly completely vocalised sounding like an [u] vowel (

through, throwing). Final dark l is regularly completely vocalised sounding like an [u] vowel ( killed, level). Final stops are typically unreleased. There is extensive glottalisation, with complete replacement of /t / even in intervocalic position or before pause (

killed, level). Final stops are typically unreleased. There is extensive glottalisation, with complete replacement of /t / even in intervocalic position or before pause ( quite, rate of). Ben regularly reduces consonant clusters to a single consonant (

quite, rate of). Ben regularly reduces consonant clusters to a single consonant ( ground, think, jump).

ground, think, jump).

LOT is tense ( lots). The happY vowel is said with a short FLEECE vowel (

lots). The happY vowel is said with a short FLEECE vowel ( actually, stories, army). THOUGHT and PALM are also tense and shorter than in other accents (

actually, stories, army). THOUGHT and PALM are also tense and shorter than in other accents ( forced to, before, half). BATH words typically have the PALM vowel (

forced to, before, half). BATH words typically have the PALM vowel ( after, half). FACE and GOAT lack a glide (

after, half). FACE and GOAT lack a glide ( rate of, commotion, most).

rate of, commotion, most).

Ben’s speech is also characterised by patterns of stress and intonation which

are typical of Singapore English. Many of these are traceable to the influence of his Chinese origins. Note the high level tones in  everybody, I’ve seen, but some people, we do. There is little reduction of unstressed syllables, giving a syllable-timing effect,

everybody, I’ve seen, but some people, we do. There is little reduction of unstressed syllables, giving a syllable-timing effect,  military training.

military training.

Track 62

Track 62Gregory: old fellow in Golden Rock – they call him Jim – and it seems as if the estate owner of the land was Mr Moore – had some grudge against him – and he always want to whip Jim – the whip man was Hercules – so any time he’s finished eat – and he having a smoke he would sit – I remember the old window that he used to sit in – he showed me – and it was a big tamarind tree right outside there – the house close this window and he used to sit there and smoke – they say you see all those holes there – in that window in the sill there – that’s where he spit his tobacco out – spit – and he said (?) rotten holes like that – he say now – when he want fun – and he finish eating – he want a smoke he light a cigar – and he call the whip man to bring Jim – he say – Har bring Jim – and they would bring old Jim – and they would tie him – a rope up in the tree and it would come down and tie Jim around his waist – and he can’t go no further than where that rope would let him go – and they would keep whipping – so when they – he start whipping him – asked well – how many lashes to give him – some time he say ah – give him a round dozen – a round dozen meaning twelve time twelve – is one forty four – hundred and forty-four lashes – say give him a round dozen – some time he would say – well – give him as much as I take a puff – each puff he take from his cigar is a lash for Jim

Interviewer: he could get away with that – just that – like that

Gregory: well he was the slave own[er] – he was the owner of the slave

Hercules: slaves were frequently given names from classical mythology. (Note the pronunciation [Bhaikles] conserving the probable eighteenth-century pronunciation: see p. 203).

round dozen: in fact this phrase means ‘twelve’ and not what Gregory believes.

Caribbean English in one form or another stretches across a large area of the Atlantic throughout the West Indies and over Guyana on the mainland of South America. There are also sizeable numbers of first-and second-generation speakers with some competence in Caribbean creoles in Britain and the USA.

Our sample comes from one of the smallest speech communities, St Eustatius in the Leeward Islands, more commonly known by its nickname of ‘Statia’. Here just over 2000 people live on a tiny island which is still a colony of the Netherlands. Dutch is the official language that everyone learns in school, and many islanders also have a knowledge of Spanish. Nevertheless, the main language of daily communication is a variety of English. Because of the official status of Dutch, there is no continuum from an acrolectal form of English through to a basilectal creole variety (as is true of Jamaica or Trinidad, for example). Our speaker, a member of the older generation, Gregory, is retelling stories that he has heard concerning one of the most notorious of the nineteenth-century slave owners.

Caribbean English divides along rhotic and non-rhotic lines, and Statian English is of the latter type ( further, there). A salient feature is the simplification of consonant clusters, heard throughout this sample, often eliminating the past tense /t d / or third person /s z/ markers of verbs (

further, there). A salient feature is the simplification of consonant clusters, heard throughout this sample, often eliminating the past tense /t d / or third person /s z/ markers of verbs ( waist, finish(ed), start(ed)). One common word with a typical Caribbean pronunciation is

waist, finish(ed), start(ed)). One common word with a typical Caribbean pronunciation is  asked [akst]. Unlike Caribbeans in, for example, Jamaica, Gregory is not a regular h-dropper. The only indication here of the frequent Caribbean uncertainty concerning the occurrence of this consonant is the hint of epenthetic /h/ in the emphatic pronunciation of

asked [akst]. Unlike Caribbeans in, for example, Jamaica, Gregory is not a regular h-dropper. The only indication here of the frequent Caribbean uncertainty concerning the occurrence of this consonant is the hint of epenthetic /h/ in the emphatic pronunciation of  owner. The realisation of /w/ is at times a labio-dental approximant (

owner. The realisation of /w/ is at times a labio-dental approximant ( whip). Th-stopping (replacement of dental fricatives by stops /t d /) is heard throughout the Caribbean, and Gregory is typical in this respect (

whip). Th-stopping (replacement of dental fricatives by stops /t d /) is heard throughout the Caribbean, and Gregory is typical in this respect ( further than).

further than).

Like most Caribbean speakers, Gregory has an open TRAP vowel ( land) – more like British than American realisations. The PALM vowel is very fronted (

land) – more like British than American realisations. The PALM vowel is very fronted ( start, cigar). The FACE and GOAT vowels are narrow diphthongs or steady-state vowels [eː oː] (

start, cigar). The FACE and GOAT vowels are narrow diphthongs or steady-state vowels [eː oː] ( take, smoke). Final /ə/ is open (

take, smoke). Final /ə/ is open ( owner [oːna]). In

owner [oːna]). In  forty, THOUGHT is open. The PRICE and MOUTH vowels consistently have the typical central starting-points of Caribbean English (

forty, THOUGHT is open. The PRICE and MOUTH vowels consistently have the typical central starting-points of Caribbean English ( light, round).

light, round).

Track 63

Track 63Aminata: To him what happened was – he went – a Dutchman in Sierra Leone – I call it – he went to Sierra Leone – he make appointment with the police – and he has appointment for one o’clock – he was there ten to one or quarter to one – and he found out the person he has appointment with was sleeping – so he was standing there – waiting – he was – he has been sleeping for two hours – and he’s still sleeping – I say – look I have an appointment one o’clock and it’s now three o’clock – I say – yes I know – I know I’m coming – so he went in – into another room – he came after forty-five minutes – so my husband has been there for – since one o’clock – didn’t (?) – his appointment was actually four o’clock – so he become so irritated he blushed and so – I said now – take it easy – this is Sierra Leone – they say one o’clock – they mean three o’clock – it’s African time – that’s what we call it – African time – never you go again when they say one o’clock – make sure you’re there three o’clock or ten past three to be precise – he says oh OK – yes and when he goes to the market – now that’s what I find terrible – he can’t buy in the market because then he has to pay three times the real price – when he goes – one day I was sick so I sent him – I said please go buy some pepper and onions and I want to make soup – so he went – he bought pepper onions tomato – and he came to me – he says it’s about fifty thousand leones – and fifty thousand leones is about twenty-five dollar – I said what – fifty thousand leones – he says yes – for onions tomato and pepper – yeah yeah – I said now – now what we’re going to do we go back – so I went with him – I was sick in my night’s (?) dress and so I – I went to the market – everybody was looking at me (?) as if I am a mad woman – I said where did you buy this – show me – because I know – well actually this man – is a white man with a black woman – so now you people sell give to me what I want for the normal price – so I end up pay five thousand leones – so he pay fifty – forty-five thousand leones extra – so I end up pay five thousand leones for a few things and I come home – yeah – since then when he went to the market – then he say my wife says – then he buy normal – otherwise

Dutchman: Aminata’s husband is Dutch.

leones: Sierra Leone’s unit of currency.

Sierra Leone has its own creole language, Krio, derived originally from English. Some Sierra Leonians are only able to speak Krio and indeed have grown up speaking it exclusively as their mother tongue. Others, like Aminata, although able to speak Krio, also speak English as a second language. They can switch easily between Krio and English, and indeed constantly vary their use of Krio and English according to the circumstances and the persons with whom they’re conversing.

Aminata has much in her English which is common to many West African countries, but some features are peculiar to Sierra Leone. Unlike most West African varieties, there is variable h-dropping ( he, his). /p k / are unaspirated and there is no devoicing of /l/ following the fortis plosives (

he, his). /p k / are unaspirated and there is no devoicing of /l/ following the fortis plosives ( appointment, o’clock, coming). The dental fricatives /0 ð/ are replaced by stops /t d /, i.e. th-stopping (

appointment, o’clock, coming). The dental fricatives /0 ð/ are replaced by stops /t d /, i.e. th-stopping ( three, thousand, with, there, this). An unusual Sierra Leone feature compared with other varieties of African English is that /r/ is uvular (

three, thousand, with, there, this). An unusual Sierra Leone feature compared with other varieties of African English is that /r/ is uvular ( irritated, dress). The accent is non-rhotic (

irritated, dress). The accent is non-rhotic ( quarter, forty-five, market).

quarter, forty-five, market).

Aminata’s realisations of vowels are typical of Sierra Leonian English. TRAP vowel is open ( mad, back, black) while STRUT is back (

mad, back, black) while STRUT is back ( onions, Dutch, coming). NURSE is a back vowel rather like NRP THOUGHT (

onions, Dutch, coming). NURSE is a back vowel rather like NRP THOUGHT ( person). The happY vowel is said with a short steady-state FLEECE vowel (

person). The happY vowel is said with a short steady-state FLEECE vowel ( forty, actually). Syllables which are unstressed in most other varieties of English are pronounced with a degree of stress and not reduced to /ə I Ʊ/ (

forty, actually). Syllables which are unstressed in most other varieties of English are pronounced with a degree of stress and not reduced to /ə I Ʊ/ ( market, African, police, woman). The BATH words are said with the PALM vowel (

market, African, police, woman). The BATH words are said with the PALM vowel ( after, past, can’t). FLEECE and GOOSE are noticeably short (

after, past, can’t). FLEECE and GOOSE are noticeably short ( sleeping, soup).

sleeping, soup).

116  Track 71 Accent detective work (Answers on website)

Track 71 Accent detective work (Answers on website)

Listen to the extracts on your audio CD. In each case, there is another voice speaking with one of the accent varieties discussed and which you have already heard. Try to locate the speaker geographically and state which particular phonetic features enable you to do this.