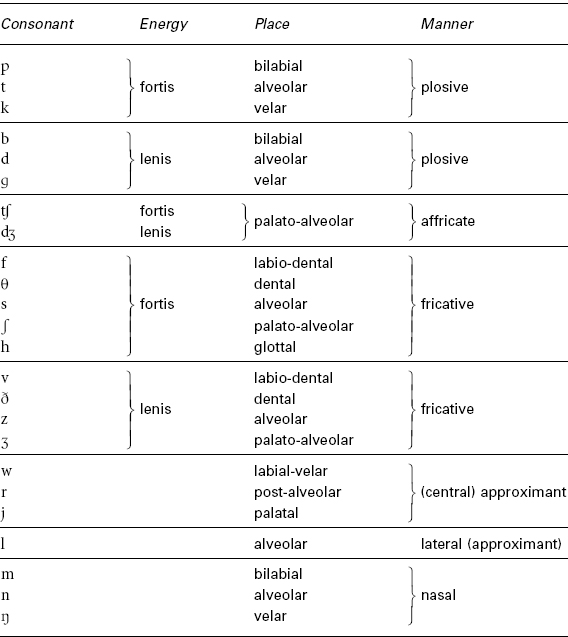

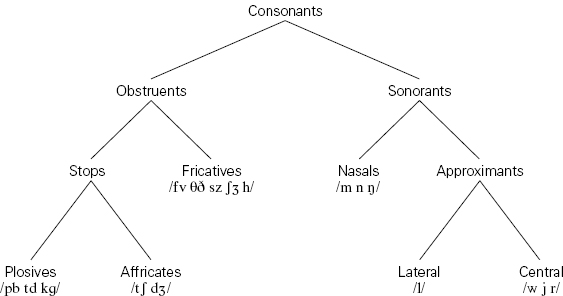

Consonants are usually referred to by brief descriptive labels stating energy, place of articulation and manner of articulation, always in that order (Table A5.1). However, we shall discuss energy of articulation last, since it’s the most complex.

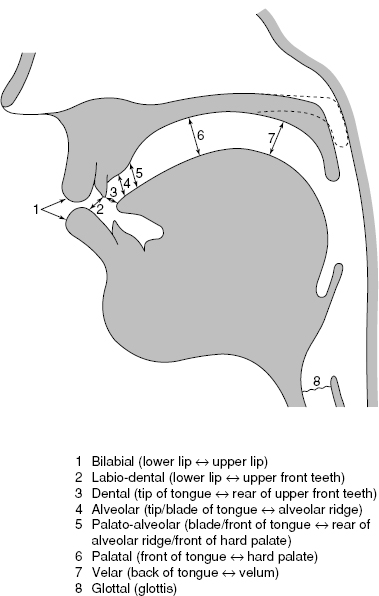

Place of articulation tells us where the sound is produced. The English places of articulation are shown in Figure A5.1 (they correspond to the column ‘Place’ in Table A5.1).

Other languages and varieties of English may have additional places of articulation. For instance, French /r/ is uvular, made with the back of the tongue against the uvula; it is symbolised phonetically as [y] and can also be heard in traditional Geordie (Tyneside) accents; see Section C2. Indian languages (and most Indian English) have retroflex sounds made with the tip of the tongue curled back against the rear of the alveolar ridge (see Section C4). Some speakers of West Country English also make /r/ in that way (see Section C2).

Some consonants have two places of articulation resulting in what is termed a double articulation. An example is English /w/ which is articulated at the lips (bilabial) and at the velum (velar) and hence is termed labial-velar.

35

Say these words and relate the consonants in bold to their places of articulation: pub (bilabial), five (labio-dental), this bath (dental), side (alveolar), rarer (post-alveolar), change (palato-alveolar), you (palatal), king (velar), how (glottal).

Table A5.1Consonant labels for English

Manner of articulation tells us how the sound is produced. All articulations involve a stricture, i.e. a narrowing of the vocal tract which affects the airstream. Table A5.2 summarises the three possible types of stricture: complete closure, close approximation and open approximation.

The active articulator is the organ that moves; the passive articulator is the target of the articulation – i.e. the point towards which the active articulator is directed. Sometimes there’s actual contact, as in [t] and [k]. In other cases, the active articulator is positioned close to the passive articulator, as in [s] or [θ]. With other articulations again, like English /r/, we find only a slight gesture by the active articulator towards the passive articulator.

Figure A5.1English consonants: places of articulation

Table A5.2Manner of articulation – stricture types

Nature of stricture |

Effect of stricture |

Complete closure |

Forms obstruction which blocks airstream |

Close approximation |

Forms narrowing giving rise to friction |

Open approximation |

Forms no obstruction but changes shape of vocal tract, thus altering nature of resonance |

The distinction of passive/active articulator isn’t always possible. For instance, [h] is formed at the glottis. The descriptive label for place of articulation is in most cases derived from the passive articulator. Figure A5.1 shows the chief places of articulation for English.

Say /t/ as in tight [taIt]. Now say /s/ as in sauce [sɔːs]. Can you feel that for /t/ the active articulator (tongue-tip/blade) and the passive articulator (alveolar ridge) block the airstream with a stricture of complete closure? But for /s/ the same articulators form a narrowing through which the airstream is channelled, i.e. a stricture of close approximation. Now say and compare the following sounds:

English /k/ in coat (complete closure)

English /k/ in coat (complete closure)

Spanish /x/, the sound spelt j in jefe (close approximation)

Spanish /x/, the sound spelt j in jefe (close approximation)

English /j/ in yes (open approximation).

English /j/ in yes (open approximation).

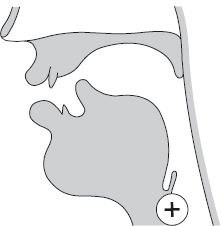

Stop consonants have a stricture of complete closure in the vocal tract which blocks (i.e. stops) the airstream, hence the term stop. The soft palate is raised so that there’s no escape of air through the nose. The compressed air can then be released in one of two ways:

The articulators part quickly, releasing the air with explosive force (termed plosion). Sounds made in this way are termed plosives, e.g. English /p t k b d g/.

The articulators part quickly, releasing the air with explosive force (termed plosion). Sounds made in this way are termed plosives, e.g. English /p t k b d g/.

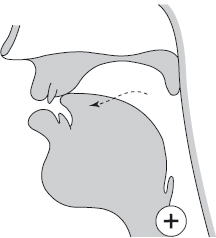

The articulators part relatively slowly, producing homorganic friction, i.e. friction at the same point of articulation. Sounds made in this way are termed affricates, e.g. English /t∫ ʤ/.

The articulators part relatively slowly, producing homorganic friction, i.e. friction at the same point of articulation. Sounds made in this way are termed affricates, e.g. English /t∫ ʤ/.

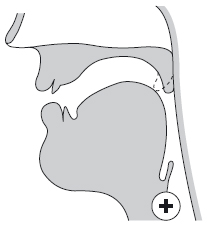

Figures A5.3 and A5.4 illustrate the stages in /t∫ ʤ/ as in church, judge. In English, /t∫/ and /ʤ/ are affricates which function as phonemes (but see also Section B2).

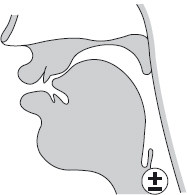

Figure A5.2Plosive [t] showing complete closure

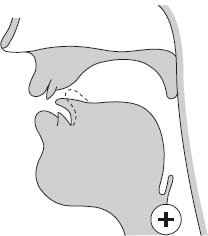

Figure A5.3Affricates [t∫] and [ʤ] showing palato-alveolar closure

Figure A5.4Affricates [t∫] and [ʤ] showing release with homorganic friction

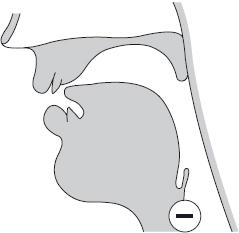

Like stops, nasals have a stricture of complete closure in the oral cavity, but the soft palate is lowered allowing the airstream to escape through the nose, e.g. English /m n ŋ/. In English, as in most languages, nasal consonants are normally voiced. However, a few languages, e.g. Burmese, Welsh and Icelandic, have voiceless nasals functioning as phonemes, i.e. / /. Note that we employ here the diacritic for voiceless

/. Note that we employ here the diacritic for voiceless  added below the symbol (above in the case of [ŋ]).

added below the symbol (above in the case of [ŋ]).

37  Track 10

Track 10

Try imitating these examples, based loosely on Burmese words: [ a] ‘notice’; [

a] ‘notice’; [ a] ‘nose’; [

a] ‘nose’; [ a] ‘borrow’. (See Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996: 111.)

a] ‘borrow’. (See Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996: 111.)

For a trill, the active articulator strikes the passive articulator with a rapid percussive (i.e. beating) action. The two types of trill that most frequently occur in language are alveolar (the tongue-tip striking the alveolar ridge) and uvular (uvula striking the back of the tongue): see Figures A5.5 and A5.6. But other kinds are possible – for instance, a bilabial trill (see Activity 38).

You should find it easy to make a bilabial trill – it’s just the brrr noise we sometimes use to mean: ‘Isn’t it cold!’ The sound has its own phonetic symbol [B]. It functions as a phoneme in a few African languages, e.g. Ngwe, spoken in Cameroon. Look in a mirror and then you’ll be able to see, as well as feel, the rapid percussive lip action.

An alveolar trill is found in Spanish, e.g. carro ‘cart’. The uvular trill [R] is occasionally heard in French – but usually only in singing. Edith Piaf, a well-known French voice from the past, was renowned for her vibrant uvular trill.

A single rapid percussive movement (i.e. one beat of a trill) is termed a tap. Spanish is unusual in having a contrast of a tap /ɾ/ and a trill /r/, e.g. caro ‘dear’ /'kaɾo/ and carro /'karo/. In many languages with trilled [r] (e.g. Welsh and Arabic) speakers regularly pronounce taps, reserving the trill for careful speech.

39  Track 11

Track 11

Try saying, between vowels, (1) an alveolar tap [aɾa] and (2) an alveolar trill [ara]. Then practise the uvular trill [R] in the same context [aRa].

One important point concerning transcription: note that in phonetic transcription the symbol for an alveolar trill, placed, of course, in square brackets, is [r]. The phonetic transcription symbol for the commonest type of English /r/ (a post-alveolar approximant, see p. 53) is an upside-down [ ]. Nevertheless, for phonemic transcription the rule is to employ the simplest letter shape possible, and consequently an ordinary /r/ (in slant brackets) is used for the English phoneme.

]. Nevertheless, for phonemic transcription the rule is to employ the simplest letter shape possible, and consequently an ordinary /r/ (in slant brackets) is used for the English phoneme.

NRP, like virtually all other types of native-speaker English, has no regular trill articulation. Scots can usually produce a trill if called upon to do so but use a tap for /r/ in everyday speech. Many British regional accents, not only Scottish, but also Liverpool, and most Welsh varieties, regularly have an alveolar tap [ɾ] for /r/. A tap was also to be heard from old-fashioned traditional RP speakers (one famous example was the legendary Noël Coward). It was used for /r/ between vowels in the middle of a word, e.g. carry, very. Indeed, a tapped [ɾ] is still sometimes taught by elocutionists (prescriptive speech trainers) as ‘correct’ speech, especially for would-be actors.

40

Some people find it hard to make an alveolar trilled [r]. Don’t despair! One way to begin is by saying a ‘flappy’ [d] using the very tip of your tongue, and as quickly as possible. Try it in words like cross, brave, proof [kdDs bdeIv pduːf]. Practise rapid ‘flappy’ [d] many times until you can change it into a true tap and then extend that into a trill.

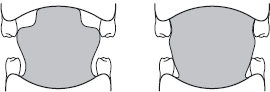

The articulators are close to each other but don’t make a complete closure. The air-stream passes through a narrowing, producing audible hiss-like friction, as in English /f v θ ð s z ∫ ʒ h/.

Compared with most varieties of English, Scottish accents have two extra fricatives [x ʍ]. The voiceless velar fricative [x] is found mostly in local usages, e.g. och! ‘oh’, loch ‘lake’ ([x] also occurs in many European languages; see Section A2). The voiceless labial-velar fricative [ʍ] occurs in words spelt wh, such as which, what, whether, wheel. It is used not only by Scots but also by many Irish and some American speakers.

Figure A5.7Fricative [s] showing narrowing at alveolar ridge

A useful term to cover both stops and fricatives is obstruents. All other consonant sounds, and also vowels, are classed as sonorants.

Figure A5.8Overview of English consonant system

Approximants have a stricture of open approximation. The space between the articulators is wide enough to allow the airstream through with no audible friction, as in English /w j r/. English /j/ and /w/ are like very short vowels – similar to brief versions of /iː/ and /uː/ (an old term for these sounds was in fact ‘semi-vowels’). Note that [j] is also termed yod after the name for the sound in Hebrew.

41

Say English /iː/ followed directly by /es/ in this way: /iː es/. If you say /iː/ quickly, you will end up with yes. Now try the same with /uː/. If you say a rapid /uː/ followed by /et/, you should end up with a sound close to /w/, and a word sounding like English wet. For non-native learners of English who don’t have /j/ or /w/ in their languages this is a good way to learn them.

In NRP, and most English regional accents, /r/ is a post-alveolar approximant – made with the tip of the tongue approaching the rear of the alveolar ridge. The phonetic symbol is [ ]. Remember that in phonemic transcription, because one tries to use simple symbol shapes wherever possible, it is shown with the ordinary letter /r/.

]. Remember that in phonemic transcription, because one tries to use simple symbol shapes wherever possible, it is shown with the ordinary letter /r/.

Figure A5.9Approximant [ ] showing post-alveolar open approximation

] showing post-alveolar open approximation

All the approximants so far described may if necessary be termed central approximants to distinguish them from the lateral approximants described below.

Lateral consonants are made with the centre of the tongue forming a closure with the roof of the mouth but the sides lowered. Typically, the airstream escapes without friction and consequently this sound is termed a lateral approximant. This is true for most allophones of English /l/, and indeed for [l] as it occurs in most languages. Consequently, the ‘approximant’ part of the label is usually omitted, and just ‘lateral’ is used. However, if there’s a narrowing between the lowered sides of the tongue and the roof of the mouth, and the air escapes with friction, the result is a lateral fricative.

Say [l] a number of times. Now try saying the sound, raising the tongue sides a little closer to the roof of the mouth, and forcing a stronger airstream through. This gives you a voiced lateral fricative, [ɮ]. Now try ‘switching off ‘the voice. This results in a voiceless lateral fricative [ɬ], which is Welsh ll. A similar sound also occurs in English (usually represented as [ ]) as an allophone of /l/, following fortis plosives, as in close, place.

]) as an allophone of /l/, following fortis plosives, as in close, place.

Lateral fricatives are unusual in the languages of the world but by no means unknown. The most familiar to you may be the notorious Welsh ll. The voiceless lateral fricative (spelt double ll, and symbolised [ɬ]) is a frequent phoneme in Welsh. You can hear it in the place-name Llanelli. It’s sometimes said to be ‘impossible’ for non-Welsh people to produce – a claim which is patently untrue, since not only do such sounds occur in many other languages but English itself has a similar articulation as an allophone of /l/; see above.

43  Track 13

Track 13

Try saying these Welsh words which contain the voiceless lateral fricative: llaeth /ɫaiθ/ ‘milk’, llaw /ɬau/ ‘hand’, llong /ɬɔŋ/ ‘ship’, allan /'aɬan/ ‘out’, ambell /'ambεɬ// ‘sometimes’.

44  Track 14

Track 14

Just for fun, try saying the longest Welsh place-name. It’s full of voiceless [ɬ] sounds:

Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch

['ɬanvairpuɬ'gwIngIɬgo'gerəxwərn’drɔbuɬ'ɬantI'sIljo'gogo'goːx]

Incidentally, the name in its present form was invented in the nineteenth century – apparently as a joke, or perhaps to bewilder the English. The official name is actually ‘Llanfairpwllgwyngyll’ – still a bit of a mouthful! But it’s known to the locals simply as Llanfair P.G. – much easier to pronounce! Even for the Welsh!

Welsh, Icelandic, Burmese, the South African languages Zulu and Xhosa, and many native American languages all have [ɬ]. The voiced lateral fricative [ɮ] is much more uncommon but does occur, for example, in Zulu and Xhosa.

Find a recording of Miriam Makeba (or another South African performer) singing folksongs in Zulu or Xhosa. Listen to it carefully and try to pick out the lateral fricatives (voiced and voiceless).

We have already mentioned in Activity 42 that English /l/ has a very common fricative allophone which is to be heard in words beginning /pl/ and /kl/. If a normally voiced phoneme is for whatever reason realised without voice, the effect is termed devoicing. As we have seen, this is shown by a diacritic in the form of a little circle, e.g. [ ].

].

46  Track 15

Track 15

Try saying these words with devoiced [ ]: clean, play, click, clock, please, plaster, plenty, cluster. Many English speakers (not all) produce a devoiced [

]: clean, play, click, clock, please, plaster, plenty, cluster. Many English speakers (not all) produce a devoiced [ ] following [t] as in atlas, rattling, cutlet. Do you?

] following [t] as in atlas, rattling, cutlet. Do you?

The third possible distinction is energy of articulation (already mentioned briefly above). The English consonants /k/ and /g/ are both velar (place of articulation) and plosives (manner of articulation), yet they’re obviously very different sounds. The same goes for /s/ and /z/, which are both alveolar fricatives, but are clearly not identical. So what’s the difference?

47  Track 16

Track 16

Listen and repeat these words a number of times: pack – back. Compare the initial sound in each word /p – b/. Which sound do you hear as the stronger, more energetic articulation? Did you also notice that there is a slight ‘puff of air’ after the release of /p/ but not after the release of /b/?

48

Say /p/ and /b/ between /aː/ vowels: /aːpaː/, /aːbaː/. Put your fingers in your ears and listen for voice. Voice ceases during /p/, but continues all the way through /b/. Now do the same for /t/ and /d/, and /s/ and /z/: /aːtaː/ and /aːdaː/, /aːsaː/ and /aːzaː/. Voice ceases for the consonants /t/ and /s/, but continues throughout for /d/ and /z/.

English has two classes of consonant sound: one of the /t k s/ type with stronger and voiceless articulation and another of the /b d z/ type whose articulation is weaker and potentially voiced. The first class is termed fortis (Latin: ‘strong’), and the second lenis (pronounced /'liːnIs/ Latin: ‘soft’). Consonants in English divide as follows (note that /h/ has no lenis counterpart).

Fortis |

Lenis |

p t k t∫ f θ s ∫ h |

b d g ʤ v ð z З |

The fortis/lenis distinction applies in English only to the obstruents (i.e. stops and fricatives). The sonorants (nasals and approximants) do not have this contrast (hence the blank spaces in the ‘Energy’ column in Table A5.1).

Most languages have a contrast of a kind similar to the fortis/lenis contrast found in English. But the exact form of the contrast varies a lot from one language to another, and there are more phonetic signals for the fortis/lenis contrast in English than in most other languages (see Table A5.3 below).

There may also be very important differences in distribution. Many languages have no word-final fortis/lenis contrasts (even where the spelling would seem to indicate this). This goes for German, Dutch and Russian. In German, Wirt – wird ‘host – becomes’ are said exactly the same and kalt – bald ‘cold – soon’ form a good rhyme. Similarly, in Dutch, hout – houd ‘wood – hold’ are pronounced identically, and maat ‘size’ rhymes with kwaad ‘angry’. Speakers of languages such as these usually have great difficulty with the frequent word-final fortis/lenis contrasts in English in pairs like life – live, rate – raid, nip – nib.

Table A5.3 summarises the main ways in which the fortis/lenis contrast is indicated in English. The factors described in this table are crucial for this contrast. Energy of articulation has been mentioned already. Aspiration and glottalisation apply only to the fortis plosives /p t k/ and will be discussed in Section B2. Let’s now examine the two remaining features, voicing and vowel length.

Table A5.3Fortis/lenis contrast in English

| Fortis | Lenis |

| 1Articulation is stronger and more energetic. It has more muscular effort and greater breath force. | 1Articulation is weaker. It has less muscular effort and less breath force. |

| 2Articulation is voiceless. | 2Articulation may have voice. |

| 3Plosives /p, t, k/ when initial in a stressed syllable have strong aspiration (a brief puff of air), e.g. pip [phIp]. | 3Plosives are unaspirated, e.g. bib [bIb]. |

| 4Vowels are shortened before a final fortis consonant, e.g. beat [bit]. | 4Vowels have full length before a final lenis consonant, e.g. bead [biːd]. |

| 5Syllable-final stops often have a reinforcing glottal stop, e.g. set down [se?t ‘daƱn]. | 5Syllable-final stops never have a reinforcing glottal stop, e.g. said [sed]. |

In English, fortis consonants are voiceless, i.e. the vocal folds do not vibrate. Lenis consonants are potentially voiced. The word ‘potentially’ is important here. In many languages the essential difference between sounds like [s] and [z], or [p] and [b], is one of voicing; /p t k f s/ etc. are voiceless while their counterparts /b d g v z/ etc. are truly voiced. This is largely true, for example, of French, Spanish, Italian and many more. In such languages, the terms used for these phonologically opposed classes are voiceless and voiced.

But in English the difference is not as clear-cut. Medially (i.e. between vowels, or other voiced sounds) lenis consonants have full voicing. Some voicing is lost in initial position, and final consonants are typically almost totally devoiced.

49  Track 17

Track 17

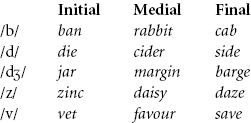

Listen and repeat the following English words and note the degree of voicing in the different contexts:

The difference in initial and final devoicing only affects lenis obstruents. The nasals /m n ŋ/, lateral /l/ and approximants /w j r/ do not undergo devoicing in the manner described following or preceding pause. Consequently, in words like ram, long, wall, moon, yell, the initial and final sounds are both fully voiced.

50 (Answers on Website)

Dad bought books, bags and magazines at Gateshead Station

[' æd 'bɔːt '

æd 'bɔːt ' Ʊks '

Ʊks ' ægə ən mægə‘'ziːnz ət '

ægə ən mægə‘'ziːnz ət ' eItshe

eItshe 'steI∫

'steI∫ ]

]

In this example, the vowels and fully voiced consonants are underlined, and those with devoicing shown by the ‘devoiced’ diacritic:  . Transcribe the following utterances and mark the consonants in the same way.

. Transcribe the following utterances and mark the consonants in the same way.

A big bag full of gold.

David rode off on Grandad’s old bike.

In all varieties of English (except Scottish: see Section C3), vowels are shortened before fortis consonants but have full length in all other contexts (i.e. word-finally, before lenis consonants, and before nasals and /l/). This pre-fortis shortening is most obvious in stressed monosyllables (i.e. single-syllable words) and is termed pre-fortis clipping.

51  Track 18

Track 18

Listen to these sets of English words. Notice how pre-fortis clipping shortens the vowels. When they are word-final or pre-lenis, they have full length. If you are a non-native English speaker, try imitating this effect using the recording as your model.

| Pre-fortis | Final | Pre-lenis |

| wheat | we | weed |

| note | no | node |

| sauce | saw | sawed |

| state | stay | stayed |

| white | why | wide |

| peace | pea | peas |

| bought | bore | bored |

| juice | Jew | Jews |

| weight | way | weighed |

| hurt | her | heard |

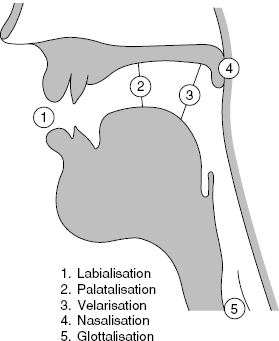

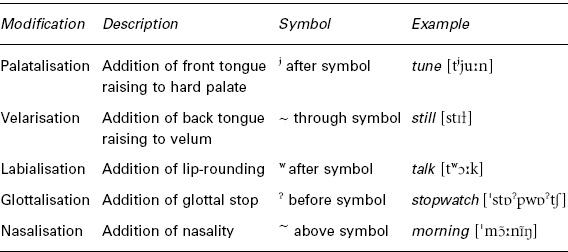

It often happens that the production of a speech sound involves certain types of modification. Besides the main articulation, there may also be an additional secondary articulation. The chief kinds of modification are listed in Figure A5.12 and also in Table A5.4. Notice that all the terms include ‘-ised’ or ‘-isation’.

Figure A5.12Secondary articulation locations

Table A5.4Secondary articulation

Labialisation adds lip-rounding and is shown phonetically with the diacritic [w] after the symbol.

52

Look in a mirror and say me. What shape are your lips? Now say more. Where does the lip-rounding begin? Now say the words door, saw, core, bore. You’ll find that lip-rounding typically starts in the consonant preceding the rounded vowel. We can show these labialised consonants as [dw sw kw bw].

53

Say the word sheep. Do you have lip-rounding for /∫/? English native speakers usually do since the lip-rounding is an essential part of the articulation of this consonant and not dependent on the following vowel.

Palatalisation adds to the main articulation the raising of the front of the tongue towards the hard palate (tongue takes on an [i]-like shape with a possible [j] off-glide). It is shown by [j] placed after the symbol.

54

Say the English words tune, dune, new, mew, assume, beautiful, putrid. These all involve palatalised consonants [tj dj nj mj sj bj pj]. (But note that for tune, dune most NRP speakers nowadays use /t∫ ʤ/; see Section B2.)

In some languages, e.g. Russian, Irish and Scots Gaelic, a set of palatalised consonants contrasts phonemically with a set of non-palatalised consonants.

French, Italian, German and Welsh have palatalised /l/ (often termed clear l) in all contexts. The same is true of most South Wales English and much southern Irish English.

Velarisation adds to the main articulation the raising of the back of the tongue towards the velum (the tongue takes on an [u]-like shape). It is shown by [~] written through the symbol, e.g. [ɫ]. Velarised /l/ is often termed dark l and is found not only in English, but also (for example) in Russian, Portuguese and Dutch.

55  Track 19

Track 19

Listen and repeat the following words in English: still, tell, shall, bull. And then these words in French: style, tel, halle, boule. Note that in this context English /l/ is dark whereas French /l/ is clear.

56

Certain varieties of English, e.g. much American and Scottish, some Australian, have a velarised dark l in all contexts. Is your word-initial /l/ clear or dark in words like leaf, lame, less, look, long? What about medial position, e.g. willow, follow, teller, sullen?

Glottalisation adds reinforcing glottal stop [?]. The English fortis stops /p t k t∫/ are regularly glottalised when syllable-final (see Section B2). Glottalisation is symbolised as [?], e.g. lipstick [lI?pstI?k].

Nasalisation adds nasal resonance through lowering the soft palate. It is shown by the diacritic [~] placed above the symbol. In English, and many other languages, vowels preceding nasals are regularly nasalised, e.g. strong man [str m

m n].

n].

Note that most writers consider as secondary articulations only the oral strictures of open approximation (e.g. labialisation, palatalisation, velarisation). We have extended the concept to cover two other articulatory modifications, i.e. glottalisation and nasalisation.

In addition to differences between individual consonants, one can also consider other characteristics of consonant articulations which have to do with the articulatory setting of a particular language. This term refers to shapings of the speech organs which are continuous throughout the speech process. Setting varies from one language to another and, within the same language, from one accent to another.

To give just a few examples:

Spanish is characterised by a dental setting (tongue-tip against front teeth) which means that sounds such as /t d n s l/ are dental rather than alveolar. (This, together with syllable-timed rhythm (see Section B6), is perhaps why English speakers have been known to refer to Spanish as sounding rather like a ‘machine gun with a lisp’!)

Spanish is characterised by a dental setting (tongue-tip against front teeth) which means that sounds such as /t d n s l/ are dental rather than alveolar. (This, together with syllable-timed rhythm (see Section B6), is perhaps why English speakers have been known to refer to Spanish as sounding rather like a ‘machine gun with a lisp’!)

Portuguese has semi-continuous nasalisation – something also found in much American English (see Section C1). European Portuguese also has notable velarisation (not obvious in the Brazilian variety).

Portuguese has semi-continuous nasalisation – something also found in much American English (see Section C1). European Portuguese also has notable velarisation (not obvious in the Brazilian variety).

In Hindi and other Indian languages there is a retroflex setting so that many articulations are made with the tip of the tongue curled back against the alveolar ridge (see pp. 194–5). This retroflex setting is also a well-known feature of almost all varieties of Indian English.

In Hindi and other Indian languages there is a retroflex setting so that many articulations are made with the tip of the tongue curled back against the alveolar ridge (see pp. 194–5). This retroflex setting is also a well-known feature of almost all varieties of Indian English.

Many types of Arabic have tongue-root retraction producing a pharyngealised setting.

Many types of Arabic have tongue-root retraction producing a pharyngealised setting.

NRP English typically has loose lips, and relaxed tongue and facial muscles – very much opposed to French with its pouting lip-rounding, and tense tongue and facial muscles (something imitated to great effect by the late Peter Ustinov in his portrayal of the French-speaking detective Hercule Poirot). A characteristic of most English is to use a tapered tongue setting for alveolar consonants with a small area of contact. Compare the blunter tongue setting for alveolars found in some other languages, e.g. Dutch, where a larger portion of the tongue is used for these sounds. The looser lip setting and the relaxed tapered tongue shape of English alveolars seem to be one reason why fortis stops in English are frequently realised with aspiration.

Setting can also vary noticeably from one language variety to another. Just within British English we can find several examples: West Country English (e.g. Bristol) often has a type of retroflex setting; South Wales English has a tendency towards palatalisation; whilst Liverpool English is velarised (Scouse is popularly termed ‘adenoidal’, presumably in reference to the voice quality induced by the velar setting). Pharyngealisation is characteristic of English as spoken in much of North Wales.

57

Transcribe phonemically, showing intonation groups and sentence stress, and using weak and contracted forms wherever possible.

Transcription Passage 5

Suddenly she came upon a little three-legged table, all made of solid glass. There was nothing on it but a tiny golden key, and Alice’s first idea was that this might belong to one of the doors of the hall. But, alas! Either the locks were too large, or the key was too small. At any rate, it would not open any of them. However, the second time round, she came upon a low curtain she had not noticed before, and behind it was a little door about fifteen inches high. She tried the little golden key in the lock, and to her great delight it fitted.