what is implied in phonetic terms

what is implied in phonetic termsWe’re moving on now from dealing with the segments – i.e. the vowel and consonant sounds – to tackling supra-segmental features, namely stress, rhythm (which we shall deal with in this section) and intonation (which we’ll come to in Section B7). Unlike vowels and consonants, which are single speech sounds, supra-segmental features normally stretch over more than a single segment – possibly a syllable, a complete word or phrase, whole sentences, or even more.

We introduced the concept of stress in Section A3 and from then on we’ve been employing it for our transcriptions – so you should be quite used to the general idea. But now let’s examine stress more closely so as to discover:

what is implied in phonetic terms

what is implied in phonetic terms

what role stress has to play in the sound system of English.

what role stress has to play in the sound system of English.

Below we shall employ the distinction first made in Section A3 between word stress (stress in the isolated word) and sentence stress (stress in connected speech).

In English, four phonetic variables appear most significant as indicators of stress: intensity, pitch variation, vowel quality and vowel duration (see Table B6.1).

/; in the second word some speakers may use another non-peripheral vowel, KIT.) Diphthongs have a less clearly discernible glide.

/; in the second word some speakers may use another non-peripheral vowel, KIT.) Diphthongs have a less clearly discernible glide.

Some degree of vowel centralisation in unstressed contexts is a feature of many languages; as a result, unstressed vowels sound somewhat ‘fuzzy’ as compared with those in stressed syllables, which retain distinct peripheral vowels on the edges of the vowel diagram. As you can see from our example above, what is unusual about English is that this process generally goes one stage further. The peripheral vowel in the unstressed syllable is actually replaced by another phoneme – most commonly by /ә/, sometimes by /I/ or /Ʊ/, or even a syllabic consonant, e.g. attention /ә’ten∫ /, excitable /Ik’saItәb

/, excitable /Ik’saItәb /. The effect is termed vowel reduction and is one of the most characteristic features of the English sound system. Neglect of vowel reduction is one of the commonest errors of non-native learners of English, and results in unstressed syllables having undue prominence.

/. The effect is termed vowel reduction and is one of the most characteristic features of the English sound system. Neglect of vowel reduction is one of the commonest errors of non-native learners of English, and results in unstressed syllables having undue prominence.

], sarcastic [sɑ’kæːstIk], TV [ti’viː].

], sarcastic [sɑ’kæːstIk], TV [ti’viː].Table B6.1Characteristics of stressed and unstressed syllables

Stressed |

Unstressed |

|

1 Intensity |

Articulation with greater breath/muscular effort Perceived as greater loudness |

Less breath/muscular effort Perceived as having less loudness |

2 Pitch |

Marked change in pitch |

Syllables tend to follow the pitch trend set by previous stressed syllable |

3 Vowel quality |

May contain any vowel (except /ә/) |

Generally have central vowels /ә I Ʊ/ or syllabic consonants |

Vowels have clear (peripheral) quality |

Vowels may have centralised quality |

|

Diphthongs have clearly defined glide |

Diphthongs tend to have a much reduced glide |

|

4 Vowel duration |

Vowels have full length |

Vowels are considerably shorter |

92 (Answers on Website)

Make phonemic transcriptions of the following pairs, noting the occurrence of non-central vowels in stressed syllables against central vowels/syllabic consonants in unstressed syllables:

compound (noun) |

(to) compound |

progress (noun) |

(to) progress |

permit (noun) |

(to) permit |

frequent (adj.) |

(to) frequent |

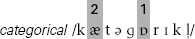

We shall distinguish two degrees of stress and ‘unstressed’, as in:

The strongest stress is primary stress (indicated by 1 in the example); the next level, secondary stress (indicated by 2) – anything else is treated as unstressed. Primary stress is normally shown by a vertical mark [‘] placed above the line (as we have been doing throughout this book). Where it’s necessary to show a secondary stress, this is shown by a vertical mark below the line, thus: [ ], e.g.

], e.g.  cate’gorical,

cate’gorical,  eccen’tricity,

eccen’tricity,  expla’nation, ‘cauli

expla’nation, ‘cauli flower, ‘goal

flower, ‘goal keeper, etc. Note that unstressed syllables are left unmarked. For most purposes, it is sufficient to show only primary stress, and from now on we shall normally ignore secondary stresses and also leave them unmarked, e.g. cateBgorical, Bcauliflower, etc.

keeper, etc. Note that unstressed syllables are left unmarked. For most purposes, it is sufficient to show only primary stress, and from now on we shall normally ignore secondary stresses and also leave them unmarked, e.g. cateBgorical, Bcauliflower, etc.

In certain languages, stress overwhelmingly falls on a syllable in a particular position in the word; we shall term this language invariable stress. For example, in Czech and Slovak, stress is normally on the first syllable; in Italian, Welsh and Polish, stress is normally on the penultimate (last but one); other languages, such as Farsi (spoken in Iran), have word-final stress. In certain languages, notably French and many Indian languages, such as Hindi and Gujarati, native speakers don’t seem to consider stress to be of significance. In French, for example, although in isolated words stress is invariably on the final syllable, things are very different in the flow of speech (see Section C6).

In English and many other languages (e.g. German, Russian, Danish, Dutch), not only can stress occur at any point in the word but, crucially, it is fixed for each individual word; this we may term lexically designated stress. In such languages, stress is furthermore of great importance for the phonetic structure of the word and cannot as a rule be shifted in connected speech.

Despite the significance of stress, it’s curious that few languages show stress in orthography (an exception is Spanish where any word which does not conform to regular Spanish stress patterns has the stressed syllable indicated by an acute accent, e.g. teléfono ‘telephone’; see Section C6). In English, although it’s often very difficult for a non-native to predict the primary stress from the written form of the word, there’s no such help. Nevertheless, native speakers are generally able to guess the stress of unfamiliar words, and this implies that there is an underlying rule system in operation, even though the rules for stress are complex and have numerous exceptions. In fact, linguists have moved from the view once held, which claimed that there were few rules for predicting English stress, to a standpoint where some would say that stress is completely predictable. However, any prescriptive rule system which aimed at being even reasonably comprehensive would have to be tremendously complex.

From the point of view of non-native learners, it’s probably best to consider English stress as being in part rule-governed, and only to concern themselves with learning the most useful and frequent patterns. Together with the guidelines which follow, the traditional advice to the non-native English learner of noting and memorising the stress pattern of words when you first meet them must still apply. Nevertheless, it is possible to note a few useful stress guidelines.

Rough guide: primary stress on first syllable, e.g. ‘culture, ‘hesitant, ‘motivate.

Rough guide: there is a tendency for the antepenultimate syllable to have primary stress, i.e. the last but two, e.g. credi’bility, com’municate, methodo’logical, etc.

Rough guide: in shorter words beginning with a prefix, the primary stress typically falls on the syllable following the prefix: inter’ference, in’tend, ex’pose, con’nect, un’veil. Exception: a large number of nouns, e.g. ‘output, ‘interlude, ‘congress, ‘absence.

Numerous verbs with prefixes are distinguished from nouns by stress. We can term this switch stress. The noun generally has stress on the prefix, while the verb has stress on the syllable following the prefix:

Verb |

Noun |

(to) in’sert |

(the) ‘insert |

(to) ex’cerpt |

(the) ‘excerpt |

(to) con’duct |

(the) ‘conduct |

(to) up’date |

(the) ‘update |

Certain word endings may act as stress attractors, falling into two groups.

ade (nouns), -ain (verbs), -ee (nouns), -eer, -esque (adjs/nouns), -esce (verbs), -ess (verbs), -ette (nouns), -ique (nouns/adjs), -oon, -self/-selves, e.g. pa’rade, ab’stain, interview’ee, engi’neer, gro’tesque, conva’lesce, as’sess, statu’ette, cri’tique, lam’poon, her’self, your’selves.

-ative, -itive, -cient, -ciency, -eous, -ety, -ian, -ial, -ic, -ical, -ident, -inal, -ion, -ital, -itous, -itude, -ity, -ive, -ual, -ular, -uous, -wards /wәdz/, e.g. al’ternative, ‘positive, ‘ancient, de’ficiency, ou’trageous, pro’priety, pe’destrian, super’ficial, melan’cholic, ‘radical, ‘accident, ‘criminal, o’ccasion, con’genital, infe’licitous, ‘multitude, incre’dulity, a’ttentive, per’petual, ‘secular, con’spicuous, ‘outwards. Note that many of these lead to antepenultimate stressing.

Incorrect stressing of compounds doesn’t normally hinder intelligibility, yet this area is a very significant source of error – even for advanced non-native learners. To provide a complete guide is impossible since there are indeed many irregularities. But knowing a few simple guidelines can make compound stress very much easier for non-natives to learn. Even if you still have to use some guesswork, it allows you to get things right, perhaps nine times out of ten.

Compounds in English are of two types: those which have their main stress on the initial element of the compound and those which have the main stress on the final element.

Initial Element Stress (IES) with main stress on the first part of the compound, e.g. ‘apple pip, ‘office boy, ‘Russian class.

Initial Element Stress (IES) with main stress on the first part of the compound, e.g. ‘apple pip, ‘office boy, ‘Russian class.

Final Element Stress (FES) with main stress on the last element of the compound, e.g. apple ‘pie, office ‘desk, Russian Bsalad. Note that many books term this ‘double stress’ or ‘equal stress’.

Final Element Stress (FES) with main stress on the last element of the compound, e.g. apple ‘pie, office ‘desk, Russian Bsalad. Note that many books term this ‘double stress’ or ‘equal stress’.

Stress Guidelines for Compounds

Compounds written as one word nearly always have IES, but those written as two words, or with a hyphen, can be of either stress type.

The most useful guides in terms of allocating stress in compounds are the ‘Manufactures Rule’ and the ‘Location Rule’.

The Manufactures Rule implies that if the compound includes a material used in its manufacture (e.g. an apple pie is a pie made of apples), then FES applies, e.g. apple ‘pie, plum ‘brandy, paper ‘bag, cotton ‘socks, diamond ‘bracelet. Compare non-manufactured items, which instead take IES, e.g. ‘apple-tree, ‘paper clip, ‘plum stone, ‘cotton-reel, ‘diamond cutter.

The Location Rule describes the strong tendency for a compound to take FES if location is in some way involved.

(a) FES applies if the first element is the name of a country, region or town: e.g. Turkish de’light, Russian rou’lette, Burmese ‘cat, Scotch ‘mist, Lancashire ‘hotpot, Bermuda ‘shorts, Brighton ‘rock, London ‘pride.

(b) The vast majority of place-names, geographical features, etc. have FES. This category includes:

regions, towns, suburbs, districts, natural features, e.g. East ‘Anglia, New ‘York, Castle ‘Bromwich, Notting ‘Hill, Silicon ‘Valley, Land’s ‘End, Botany ‘Bay.

regions, towns, suburbs, districts, natural features, e.g. East ‘Anglia, New ‘York, Castle ‘Bromwich, Notting ‘Hill, Silicon ‘Valley, Land’s ‘End, Botany ‘Bay.

bridges, tunnels, parks, public buildings and sports clubs, e.g. Hyde ‘Park, (the) Severn ‘Bridge, Paddington ‘Station, Carnegie ‘Hall, Manchester U’nited.

bridges, tunnels, parks, public buildings and sports clubs, e.g. Hyde ‘Park, (the) Severn ‘Bridge, Paddington ‘Station, Carnegie ‘Hall, Manchester U’nited.

all street names, except street itself, e.g. Church ‘Road, Trafalgar ‘Square, Thorner ‘Place, Churchill ‘Way, Fifth ‘Avenue. Cf. ‘Church Street, Tra’falgar Street, etc.

all street names, except street itself, e.g. Church ‘Road, Trafalgar ‘Square, Thorner ‘Place, Churchill ‘Way, Fifth ‘Avenue. Cf. ‘Church Street, Tra’falgar Street, etc.

(c) Parts of a building tend to have FES, e.g. back ‘door, bedroom ‘window, garden ‘seat, office ‘chair. Exceptions: compounds with -room are IES, e.g. ‘living room, ‘drawing room (but front ‘room).

(d) FES applies where positioning of any sort is involved, e.g. left ‘wing, upper ‘class, bottom ‘line, Middle ‘Ages. Time location also tends to FES, e.g. morning ‘star, afternoon ‘tea, January ‘sales, April ‘showers, summer ‘holiday.

93

Think of more examples of the Manufactures Rule and the Location Rule. Can you think of any counter-examples not already mentioned? In many cases, you can get help from a pronunciation dictionary, such as the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (Wells 2008) or the Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (Jones 2011).

(1) The vast majority of food items have FES, e.g. poached ‘egg. Note that these are often covered by either the Manufactures Rule or the Location Rule, e.g. Worcester ‘sauce, Welsh ‘rabbit, Christmas ‘pudding, fish ‘soup. Exceptions: some items take IES because they can also be regarded as part of the living plant or animal, e.g. ‘chicken liver, ‘orange juice, ‘vine leaves. Other significant exceptions are: -bread, -cake, -paste, e.g. ‘shortbread, ‘Christmas cake, ‘fish paste.

(2) Names of magazines, newspapers, etc. have FES (many involve place or time and are covered by the Location Rule), e.g. (the) Daily ‘Post, (the) Western ‘Mail, (the) Straits ‘Times, Vanity ‘Fair, (the) New ‘Statesman.

(3) IES applies to compounds including the names of academic subjects, skills, etc, e.g. ‘technical college, BFrench teacher (i.e. a person who teaches French).

(4) Nouns formed from verb + particle take IES, e.g. ‘make-up, ‘come-back, ‘look-out, ‘backdrop. Exceptions are few, but note: lie-’down, look-’round, set-’to. These patterns have changed in the recent history of the language. See Section C5.

(5) Nouns ending in -er or -ing +particle take FES, e.g. hanger-’on, passer-’by, washing-’up.

(6) Compounds formed from -ing + noun are of two types:

IES applies where an activity is aided by the object (i.e. a ‘sewing machine helps you to sew), e.g. ‘sewing machine, ‘running shoes, ‘scrubbing brush, ‘washing machine.

IES applies where an activity is aided by the object (i.e. a ‘sewing machine helps you to sew), e.g. ‘sewing machine, ‘running shoes, ‘scrubbing brush, ‘washing machine.

FES applies where a compound suggests a characteristic of the object, with no idea of aiding an activity, e.g. leading ‘article, running ‘water, casting ‘vote, sliding ‘scale.

FES applies where a compound suggests a characteristic of the object, with no idea of aiding an activity, e.g. leading ‘article, running ‘water, casting ‘vote, sliding ‘scale.

When discussing transcription (Section A3) we noted that many of the potential stresses of word stress are lost in connected speech (i.e. sentence stress). The general pattern is that words which are likely to lose stress completely are those which convey relatively little information. These are the words important for the structure of the sentence, i.e. the function words (articles, auxiliary verbs, verb be, prepositions, pronouns, conjunctions). The content words (nouns, main verbs, adjectives, most adverbs), which carry a high information load, are normally stressed.

I’ve ‘heard that ‘Jack and ‘Jane ‘spent their ‘holidays in Ja’maica.

FFCFCFCCFCFC

(C = content word, F = function word)

There are certain exceptions to the general pattern stated above:

These particular function words often add significant information; the demonstratives also provide contrast.

I said give ‘her a kiss, not ‘him.

Would you call yourself a jazz lover?

Actually, I know very little a’bout jazz. I prefer classical music.

It is noteworthy that repeated lexical items are not generally stressed:

There have been ‘traffic jams in ‘Dagenham and ‘areas ‘close to Dagenham.

A similar effect can be heard in items which are direct equivalents:

Are you ‘fond of ‘chocolate then?

‘Given the ‘chance, I’ll ‘eat ‘tons of the stuff.

I’ve heard that ‘Jack and ‘Jane spent their ‘holidays in Ja’maica.

Sentence stress is the basis of rhythm in English. Stressed syllables tend to occur at roughly equal intervals of time. This is because the unstressed syllables in between give the impression of being compressed if there are many and expanded if there are few.

94  Track 25

Track 25

Say the following sentences (stressed syllables are indicated by __; unstressed by •). Take a pencil and tap out the stresses.

‘Jimmy’s ‘bought a ‘house near ‘Glasgow.

• –– • –– • –– •

‘Sally’s been ‘trying to ‘send you an ‘e-mail.

–– • • –– • • –– • • –– •

‘Alastair ‘claimed he was ‘selling the ‘company.

–– • • –– • • –– • • –– • •

Notice how the stressed syllables give the impression of coming at regular intervals; if you pronounce the words in a regular ‘singsong’ manner, it’s possible to tap out the rhythm with a pencil. Try doing so. We term this effect stress-timing, and it’s characteristic of languages such as English, Dutch, German, Danish, Russian, and many others.

Related to this feature is the variable length of vowels in polysyllabic words. Look at the following example, and notice how the syllables compress as more are added. (The lines underneath give an approximate indication of vowel length.)

The ban’s back in place |

The banner’s back in place |

The banister’s back in place |

/bænz/ |

/'bænәz/ |

/'bænIstәz/ |

––– |

–– • |

–– • • |

95

Say these words, noting how the vowel tends to shorten somewhat as unstressed syllables are added.

______ |

_____ |

___ |

mean |

meaning |

meaningful |

see |

seedy |

seedily |

red |

ready |

readily |

myrrh |

murmur |

murmuring |

One area in which stress timing reveals itself in English is the way it forms the basis of rhythm in verse – the metre, to use the technical term. To analyse English poetry written in the traditional manner, you note the beats on stressed syllables – and this applies whether we’re dealing with Shakespeare or a nursery rhyme. In the verses below, the strong beats are shown in bold. There’s always room for variation when reciting poetry, but the rendering below would be a typical way of reading these lines from a nursery rhyme and a piece of comic verse.

For the most part, the stresses fall on the content words, whereas the function words usually lack stressing. In terms of timing, the intervals between the strong beats of the stresses are roughly equal. See how, where you have a sequence of more than one weak syllable, as in ‘everywhere that’ and ‘but it’, the weak syllables compress, taking up much less time. Note also how the rhythm reflects the use of weak forms, as can be seen when the verse is transcribed phonemically.

96  Track 27

Track 27

Listen to the recording on the CD and recite the poems in the same manner, being careful to give more weight to the stressed syllables.

Mary had a little lamb –

Its feet were white as snow.1

And everywhere that Mary went,

The lamb was sure to go

‘mε:ri ‘hæd ә ‘lIt ‘læm |

‘læm |

Its ‘fiːt wә ‘waIt әz ‘snәƱ |

әnd ‘evrIwε: ðәt ‘mε:ri ‘went |

ðә ‘læm wәz ‘∫ɔː tә ‘gәƱ

I eat my peas with honey.

I’ve done so all my life.

It makes the peas taste funny,

But it keeps them on the knife.

aI ‘iːt maI ‘piːz wIð ‘hΛni |

aIv ‘dΛn sәƱ ‘ɔːl maI ‘laIf |

It ‘meIks ðә ‘piːz teIst ‘fΛni |

bәt It ‘kiːps ðәm ‘Dn ðә ‘naIf |

Follow up this activity by finding some other simple verse of the same kind. Mark the stresses and read it accordingly.

Other languages work on a different principle, syllable-timing, giving the impression of roughly equal length for each syllable regardless of stressing. Take this example from French:

Je voudrais descendre au prochain arrêt s’il vous plaît  Track 26

Track 26

/Ʒvudre dε’s dr | o prɔ∫εn a’re | si vu ‘ple |/

dr | o prɔ∫εn a’re | si vu ‘ple |/

Here each syllable appears to have approximately equal time value, except for the final one of each group, which is extended. Other languages with a tendency to equal syllable length are: Spanish, Greek, Turkish, Polish, Hindi, Gujarati.

Stress-timing appears to operate for all types of English spoken by native speakers, possibly with the exception of those strongly influenced by Creoles, such as the English of the West Indies. Some types of English employed as a second language (e.g. the English used by many Indians and Africans) absorb the syllable-timing of the mother tongue of the speakers, but such varieties can be very difficult for others to understand. As has been shown, stress-timing is achieved mainly by lengthening certain vowels at the expense of others: vowels tend to be lengthened in stressed syllables and shortened in unstressed syllables.

97

Transcribe phonemically, showing intonation groups and sentence stress, and using weak and contracted forms wherever possible.

Transcription Passage 11

‘Come on, there’s no use crying like that!’ said Alice to herself, rather sharply. ‘I advise you to leave off this minute!’ She generally gave herself very good advice (though she very seldom followed it), and sometimes she scolded herself so severely as to bring tears into her eyes; and once she remembered trying to box her own ears for having cheated herself in a game of croquet she was playing against herself, for this curious child was very fond of pretending to be two people. ‘But it’s no use now,’ thought poor Alice, ‘to pretend to be two people! Why, there’s hardly enough of me left to make one respectable person!’

1 A more common version of the second line of this rhyme is: ‘its fleece was white as snow’. Say it with those words if you prefer – it doesn’t, of course, affect the stress and rhythm in any way.