A word of more than one syllable is termed a polysyllable. When an English polysyllabic word is said in its citation form (i.e. pronounced in isolation) one strongly stressed syllable will stand out from the rest. This can be indicated by a stress mark ['] placed before the syllable concerned, e.g. 'yesterday /'jestədeI/, to’morrow /tə’marəƱ/, to’day /tə’deI/.

10 (Answers on Website)

Say these English words in citation form. Which syllable is the most strongly stressed? Mark it appropriately: manage, final, finality, resolute, resolution, electric, electricity.

Stress in the isolated word is termed word stress. But we can also analyse stress in connected speech, termed sentence stress, where both polysyllables and mono-syllables (single-syllable words) can carry strong stress while other words may be completely unstressed. We shall come back to examine English stress in more detail in Section B6. At this point we just need to note that the words most likely to receive sentence stress are those termed content words (also called ‘lexical words’), namely nouns, adjectives, adverbs and main verbs. These are the words that normally carry a high information load. We can contrast these with function words (also called ‘grammar words’ or ‘form words’), namely determiners (e.g. the, a), conjunctions (e.g. and, but), pronouns (e.g. she, them), prepositions (e.g. at, from), auxiliary verbs (e.g. do, be, can). Function words carry relatively little information; their role is holding the sentence together. If we compare language to a brick wall, then content words are like ‘bricks of information’ while function words act like ‘grammatical cement’ keeping the whole structure intact. Unlike content words, function words for the most part carry little or no stress. Only two types of function words are regularly stressed: the demonstratives (e.g. this, that, those) and wh-interrogatives (e.g. where, who, which, how). Note, however, that when wh-words and that are used as relatives they are unstressed, e.g. the girl who lent me the yellow hat that I wore to your wedding.

Certain function words are pronounced differently according to whether they are stressed or unstressed. Although few in number, they are of very high frequency. Look at this example:

Megan had decided to fetch them from the hospital

/'megən əd də’saIdId tə ‘fet∫ ðəm frəm ðe ‘haspIt /

/

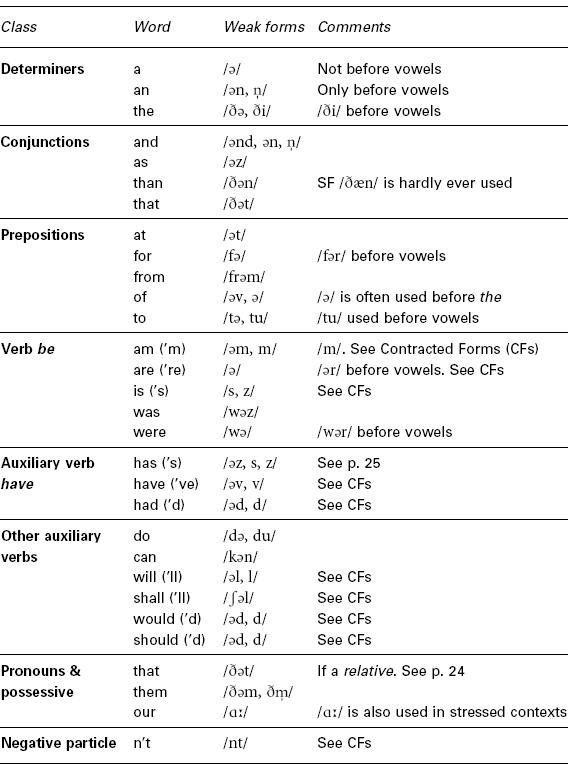

Here the words had, to, them, from, the are all unstressed and reduced to /əd tə ðəm frem ðə/. When in citation form, or stressed, these would instead be /hæd tuː ðem frbm ðiː/. The reduced, unstressed pronunciation is termed the weak form (often abbreviated to WF); while the full pronunciation characteristic of stressed contexts is called the strong form (often abbreviated to SF). A select list of the commonest weak forms is given in Table A3.1 (we have restricted it to those that are necessary for native-speaker English).

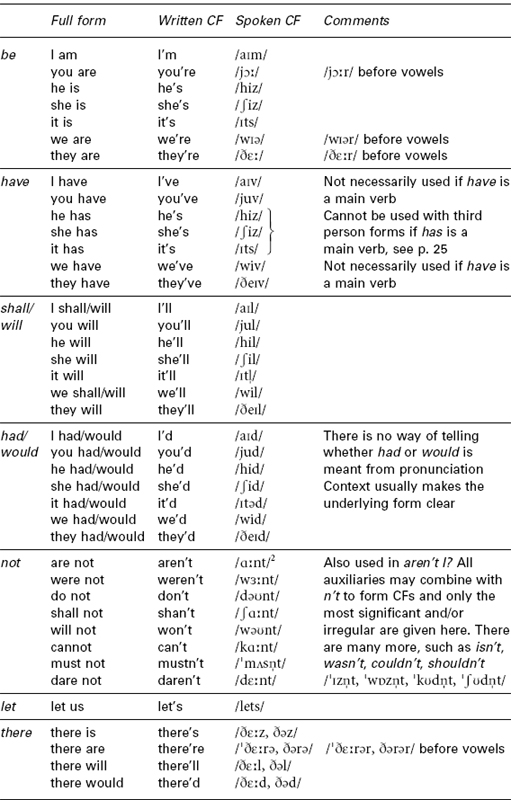

Many function words can combine with other function words, so producing contracted forms (often abbreviated to CF, also called ‘contractions’), e.g. he + will → he’ll, do + not → don’t. Unlike weak forms, contracted forms can be stressed – and indeed frequently are. All contracted forms have orthographic representations including an apostrophe. These spellings are regularly used in dialogue, and often in informal writing, but only sporadically in other kinds of written English. You may have noticed that we use them quite a lot in this book. Table A3.2 provides a list of the most common English contracted forms.

If you’re a non-native learner of English, remember that weak and contracted forms are necessary for anyone with the goal of approaching fluent native-speaker English. It’s certainly fair to argue that they are of less significance to a person learning English as a ‘lingua franca’ (see Jenkins 2000) – namely, a basic form of communication. But we assume that people reading this book will either be native speakers (in which case you’ll want to know about these features of your language), or if you are a non-native you’ll be aiming at more than bare intelligibility.

Among the languages of the world, English is remarkable for the number of its weak and contracted forms and the frequency of their occurrence. Using them appropriately doesn’t come easily to non-native learners. Even if a language does have weak forms (like Dutch, for instance) it’s unlikely that the system will be as complex or extensive as in English.

Note that, in English, weak and contracted forms are in no way confined to very informal contexts, nor are they ‘slang’ or ‘lazy speech’, as some people mistakenly believe. Avoidance of contracted forms is perhaps even more immediately noticeable than not using weak forms. Again, as a non-native, you will usually not be misunderstood, but it will certainly make your English sound less effective.

Table A3.1Essential weak forms

Remember that WFs and CFs are far more frequent than SFs. Bearing that in mind, look at this summary of their usage.1

1WFs are used only if the function word is unstressed. Otherwise SFs must be used, e.g.

It turned out that it was possible /It tзːnd ‘aƱt ðət It ‘wDz pDsəb /

/

2SFs are used at the end of the intonation group (see B7, ‘The Structure of Intonation Patterns in English’), even if the word is unstressed.

What was she getting at? /'wDt wəz ∫i 'getIŋ æt/

Pronouns form an exception in this respect, retaining the WF even in final position.

Jenny collected them /'ʤeni kə'lektId ðəm/

3Remember that demonstrative that invariably has SF (even if unstressed).

That’s the best approach to the problem /ðæts ðə ‘best ə’prəƱt∫ te ðə ‘prDbləm/

Relative pronoun that and conjunction that always have WFs, e.g.

The furniture that we ordered hasn’t arrived /ðə ‘fзːnIt∫ə ðət wi ‘ɔːdəd hæz t ə’raIvd/ Christopher told me that he’d written two books /'krIstəfə ‘teƱld mi ðət id ‘rIt

t ə’raIvd/ Christopher told me that he’d written two books /'krIstəfə ‘teƱld mi ðət id ‘rIt ‘tuː ‘bƱks/

‘tuː ‘bƱks/

4WFs ending in /ə/, e.g. to, for /tə fə/, take on different forms before vowels (see Table A3.1).

5In WFs of words spelt with initial h, i.e. verb forms have, has, had, pronouns he, his, him, her, pronouncing /h/ is variable. The /h/ forms occur without exception at the beginning of an utterance but in other contexts both /h/ and /h/-less forms can be heard; see also p. 127. (The use of a great many /h/ forms in colloquial English tends to sound somewhat over-careful.)

11

In which of the following auxiliary verbs and pronouns (all spelt with h) would English speakers actually pronounce /h/? And where would it be dropped?

Jack’s handed him the money.

Tom’s handed her the money.

He’s handed Jack the money.

Has he handed her the money?

Would he have handed her the money?

Would she have told him about having been handed the money?

I haven’t handed her any of his money.

He hasn’t had any of her money.

Discuss your responses with the other members of your class. Does everybody come up with the same patterning? If there are any differences, where are they to be found?

6Have/has when used as a main verb implying possession usually retains SF, e.g. I have an interesting bit of news /aI ‘hæv ən ‘IntrəstIŋ ‘bIt əv ‘njuːz/. While have occasionally enters into CFs (e.g. I’ve an interesting bit of news /aIv en ‘IntrəstIŋ ‘bIt əv ‘njuːz/), this is never the case with has; compare the inappropriate: *She’s an interesting piece of news – which would mean something quite different! (Note, incidentally, that the asterisk * is used in linguistic work to indicate unacceptable forms.) Do/does behaves in a similar manner. When used as a main verb, the strong form is used, e.g. What are they going to do about it? /'wDt ə ðeI ‘gəƱIŋ tə ‘duː ə’baƱt It/.

See the ‘Brief Transcription Guide’ below for the regular pronunciation patterns of’s in weak forms of has and is.

7Notice that a few common function words have no regular WF. These include: if, in, on, one, then, up, when, what, with.

Now that you know something about stress, and also have a knowledge of the crucial matter of weak/contracted forms, you’re ready to move on from transcribing isolated words to doing a phonemic transcription of a short passage of English. This will enable us to show features of real connected speech such as sentence stress and also all the WFs and CFs. For further detail on other features of connected speech, e.g. assimilation and elision, see Section B5.

Here’s a short extract (slightly adapted) from Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (Ch. 6), shown first of all in an orthographic version (i.e. in ordinary spelling) and then in phonemic transcription. Note that our transcription is only one possible version – there can be quite a lot of freedom in such matters as stressing, the choice of alternative pronunciations, and much else besides.

‘How do you know I’m mad?’ said Alice.

‘You must be,’ said the cat, ‘or you wouldn’t have come here.’

Alice didn’t think that proved it at all. However, she went on, ‘And how do you know that you’re mad?’

‘To begin with,’ said the cat, ‘a dog’s not mad. You grant that?’

‘I suppose so,’ said Alice.

‘Well, then,’ the cat went on, ‘you see a dog growls when it’s angry, and wags its tail when it’s pleased. Now I growl when I’m pleased, and wag my tail when I’m angry. Therefore I’m mad.’

‘I call it purring, not growling,’ said Alice.

‘Call it what you like,’ said the cat.

Track 5

Track 5'haƱ ʤu1 'nəƱ aIm 'mæd | sed 'ælIs||

ju 'mΛs2 bi | sed ðə 'kæt | ɔː ju 'wƱd t əv 'kΛm hIə ||

t əv 'kΛm hIə ||

'ælIs 'dId t θIŋk ðæt 'pruːvd It ə 'tɔːl3 || haƱ'evə |∫i went 'Dn | ən 'haƱ ʤu1 'nəƱ ðət 'jcː 'mæd ||

t θIŋk ðæt 'pruːvd It ə 'tɔːl3 || haƱ'evə |∫i went 'Dn | ən 'haƱ ʤu1 'nəƱ ðət 'jcː 'mæd ||

tə bə'gIn wIð | sed ðə 'kæt | ə 'dDgz nDt 'mæd || ju 'graːnt 'ðæt ||

aI sə'pəƱz 'seƱ | sed 'ælIs ||

'wel ðen | ðə 'kæt went 'Dn | ju 'siː | ə 'dDg 'graƱlz wen Its 'æŋgri | ən 'wægz Its 'teIl wen Its 'pliːzd || naƱ aI 'graƱl wen aIm 'pliːzd | ən 'wæg maI 'teIl wen aIm 'æŋgri || 'ðεːfɔː r4 aIm 'mæd ||

'aI kɔːl It 'pзːrIŋ | nDt 'graƱlIŋ | sed 'ælIs ||

'kcːl It wDt∫u1 'laIk | sed ðə 'kæt ||

1See Section B5, ‘Patterns of Assimilation in English’, for information on assimilations.

2See Section B5, ‘Elision’ and ‘Patterns of Elision in English’, for information on elision.

3This phrase has a fixed pronunciation with stress as shown.

4See Section B5, ‘Liaison’, for information on linking r.

This simplified survey is intended to start you off doing transcription and deals with some frequent beginners’ problems. Several ofs the points mentioned in passing here are discussed at greater length later on in the book.

Transcription may be from a text in conventional orthography.

1 Read the passage aloud to yourself a number of times.

2 In transcribing, you must always remember that you are dealing with connected speech and not a string of isolated words. First, mark off with a single vertical bar the breaks between intonation groups (see Section B7, ‘The Structure of Intonation Patterns in English’). These normally occur where in reading it would be possible to make a brief pause. Sentence breaks are shown by a double bar.

A most important thing to remember | is to clean the filter frequently. || This will ensure | that the machine runs efficiently at all times. ||

Note that for any written text, there are usually several different possibilities for division into intonation groups. See Section B7 for more detail.

3 Using the orthographic text, mark the stressed syllables as found in connected speech (i.e. sentence stress). This is different from stress in the isolated word as indicated in the dictionary (word stress). Sentence stress is most likely to fall on a syllable of content words (i.e. nouns, main verbs, adjectives, most adverbs). Function words (except for demonstratives, e.g. this, those, and wh-words used in questions, e.g. what, where, who) are typically unstressed. Mark sentence stress thus [B] before the stressed syllable, e.g.

A ‘most im’portant ‘thing to re’member | is to ‘clean the ‘filter ‘frequently. || This will en’sure | that the ma’chine ‘runs e’fficiently | at ‘all ‘times. ||

4 Now begin transcribing into phonemic symbols. If in doubt about a difficult word, make an attempt at it but go back later and check in any dictionary showing pronunciation in phonemic transcription (e.g. the Longman Pronunciation Dictionary: Wells 2008). Note that there may be minor differences between the transcription system used in your dictionary and the one in this book. Your dictionary may also show alternative pronunciations, possibly by superscript or italic letters. Don’t indicate all these variants; just choose one of the possibilities.

For phonemic transcription of actual speech, e.g. dictation from your instructor, or an audio recording, you must bear the following points in mind.

1 Listen to the whole passage several times. Mark intonation group boundaries. Then concentrating on one intonation group at a time, mark sentence stress.

2 Remember that in transcribing a passage of spoken language, you cannot (as you can with a written text) choose between a variety of interpretations. You must try to render faithfully in phonemic transcription exactly what the speaker has uttered. Bearing this point in mind, proceed as for a written text.

1 Always use the letter shapes of print rather than those of handwriting.

2 Take care with the following symbols: ə ɔ I Ʊ з ε æ a D ∫ З θ ð g. Make sure that you don’t confuse these letter shapes:

I i εз ə a æ ɑ a z З З з θ ə ɔ Ʊ u m ʍ s ∫ D ɔ D

3 Here are a few hints on how to write some of the symbols:

D is like b without an ascending stroke.

θ is written as 0 with a cross-stroke.

ð is like a reversed 6 with a cross-stroke.

f should not descend below the line.

First the do’s

Do use weak and contracted forms wherever possible.

Do use weak and contracted forms wherever possible.

Do show syllabic consonants with the syllabic mark: bottle /‘bDt

Do show syllabic consonants with the syllabic mark: bottle /‘bDt ]/, written /'rxt

]/, written /'rxt /. The most frequent syllabic consonants in NRP are /l n/; syllabic /m/ and /ŋ/ are less commonly found. Syllabic /r/ is very common in General American and other rhotic accents.

/. The most frequent syllabic consonants in NRP are /l n/; syllabic /m/ and /ŋ/ are less commonly found. Syllabic /r/ is very common in General American and other rhotic accents.

Do transcribe numbers or abbreviations in their full spoken form. Note that in abbreviations the stress always falls on the last item, e.g. CD /siː ‘diː/, CNN /siː en 'en/.

Do transcribe numbers or abbreviations in their full spoken form. Note that in abbreviations the stress always falls on the last item, e.g. CD /siː ‘diː/, CNN /siː en 'en/.

Now the don’ts

Don’t use any capital letters or show any punctuation.

Don’t use any capital letters or show any punctuation.

Don’t include c o q x y, which don’t occur in our English NRP phonemic transcription system. (Note that these symbols are used for sounds in other languages.)

Don’t include c o q x y, which don’t occur in our English NRP phonemic transcription system. (Note that these symbols are used for sounds in other languages.)

Don’t use phonetic symbols, e.g. [?

Don’t use phonetic symbols, e.g. [?  ɫ], in a phonemic transcription.

ɫ], in a phonemic transcription.

1 In our transcription system for English NRP, /ə/ occurs only in unstressed syllables. In stressed syllables you will generally find /Λ/ or /зː/, e.g. butter /'bΛte/, burglar /'bзːglə/.

2 In NRP, and similar accents, /r/ only occurs before a vowel, e.g. fairy /'fεːri/, but far /faː/, farm /faːm/. (See Section B2.) To indicate the possibility of linking r (see B5), many dictionaries use superscript r, e.g. /faːr/. You should never write the superscript r, but instead where there is linking r transcribe it between words with a full-size letter, e.g. far off /faː r 'Df/.

3 The 'happY words’ (see Section B3), ending in -y, -ie or -ee, have a vowel between KIT /I/ and FLEECE /iː/, as do inflectional -ies and -ied. This neutralised phoneme (see Section B1) is indicated by the symbol i, e.g. silly /'sIli/, caddie /'kædi/, coffee /'kDfi/, fairies /'fεːriz/, married /'mærid/. Similarly, words like graduate, influence have a vowel between /Ʊ/ and /uː/, shown by the symbol u, e.g. influence /'Influens/. Note that the neutralised vowels occur also in certain weak forms (see Table A3.1, p. 22).

4 The pronunciation of written s in plurals and verb endings, and ‘s found in possessives, contracted forms, and the weak forms of has and is, is governed by the preceding sound.

Following /s z ∫ З t∫ ʤ/, s →/Iz/, e.g. buses /'bΛsIz/, wishes /'wI∫Iz/, George’s /'ʤɔːʤIz/.

Following /s z ∫ З t∫ ʤ/, s →/Iz/, e.g. buses /'bΛsIz/, wishes /'wI∫Iz/, George’s /'ʤɔːʤIz/.

Following the fortis consonants /p t k f θ/, s → /s/, e.g. Jack’s boots /'ʤæks ‘buːts/, Pat’s gone /'pæts ‘gDn/.

Following the fortis consonants /p t k f θ/, s → /s/, e.g. Jack’s boots /'ʤæks ‘buːts/, Pat’s gone /'pæts ‘gDn/.

In all other cases, s → /z/, e.g. roads /rəƱdz/, dreams /driːmz/, Sue’s /suːz/, Jane’s leaving /'ʤeInz ‘liːvIŋ/.

In all other cases, s → /z/, e.g. roads /rəƱdz/, dreams /driːmz/, Sue’s /suːz/, Jane’s leaving /'ʤeInz ‘liːvIŋ/.

5 The ending -ed has the following patterning:

Following /t/ and /d/, -ed → /Id/, e.g. folded /'fəƱldId/, waited /'weItId/.

Following /t/ and /d/, -ed → /Id/, e.g. folded /'fəƱldId/, waited /'weItId/.

Following fortis consonants (except /t/), -ed → /t/, e.g. looked /lƱkt/, laughed /laːft/.

Following fortis consonants (except /t/), -ed → /t/, e.g. looked /lƱkt/, laughed /laːft/.

Following all other consonants or vowels, -ed → /d/, e.g. seemed /siːmd/, pleased /pliːzd/, saved /seIvd/, barred /baːd/.

Following all other consonants or vowels, -ed → /d/, e.g. seemed /siːmd/, pleased /pliːzd/, saved /seIvd/, barred /baːd/.

For several adjectives, -ed → /Id/, e.g. crooked /'krƱkId/, naked /'neIkId/. Other examples are: ragged, aged, jagged, -legged (as in four-legged, bow-legged), rugged, wicked, learned, cursed, blessed, beloved.

6 A number of verbs ending in n or l have two pronunciations and sometimes two spelling forms for the past tense, one in -ed and one in -t, e.g. spelled/spelt; burned/ burnt. In British English, the pronunciation with /t/ is more common; American English favours /d/.

7 If transcribing from an audio recording, you must show all assimilations and elisions you can hear. When transcribing from a written text, it adds interest to show assimilations and elisions where these are possible (see Section B5).

Passages (slightly adapted from Alice in Wonderland, Ch. 1), graded in length, have been provided for you to use for transcription practice in the course of reading this book. Three are given below to start you off, and from then on there is an activity of this sort at the end of every unit in Sections A and B. Mark sentence stress and intonation group boundaries. Show contracted forms wherever possible, even if not indicated as such in the text (i.e. transcribe could not as /kƱdn /). Keys (based on NRP) to all the transcriptions are to be found on the website.

/). Keys (based on NRP) to all the transcriptions are to be found on the website.

12

Transcribe phonemically, showing intonation groups and sentence stress, and using weak and contracted forms wherever possible.

Transcription Passage 1

And here Alice began to get rather sleepy, and went on saying to herself, in a dreamy sort of way, ‘Do cats eat bats?’ and sometimes, ‘Do bats eat cats?’. For, you see, as she couldn’t answer either question, it didn’t much matter which way she put it.

Transcription Passage 2

She felt that she was dozing off, and had just begun to dream that she was walking hand in hand with Dinah, her cat. She was saying to her very earnestly, ‘Now, Dinah, tell me the truth. Did you ever eat a bat?’, when suddenly – thump! Down she came on a heap of sticks and dry leaves, and the fall was over.

Transcription Passage 3

Alice was not a bit hurt, and she jumped up on to her feet in a moment. She looked up, but it was all dark overhead. In front of her was another long passage, and the White Rabbit was still in sight, hurrying down it. There was not a moment to be lost. Away went Alice like the wind. She was just in time to hear it say, as it turned a corner, ‘Oh my ears and whiskers, how late it’s getting!’

1A more detailed treatment of this topic is to be found online, ‘Weakform words and contractions for the advanced EFL user’, www.yek.me.uk/wkfms.html.

2The older CF of aren’t and isn’t was ain’t – a form now heard only in regional varieties.