All languages modify complicated sequences in connected speech in order to simplify the articulation process – but the manner in which this is done varies from one language to another. Furthermore, most native speakers are totally unaware of such simplification processes and are often surprised (or even shocked!) when these are pointed out to them.

The differences between the citation forms and the modified connected speech forms are not just a matter of chance: clear patterns are distinguishable.

87  Track 24

Track 24

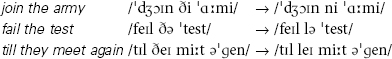

Try saying these English words and phrases, first following the transcription in column 1 and then in column 2.

1 Citation forms |

2 Connected speech forms |

|

headquarters |

/hed ‘kwɔːtәz/ |

/heg ‘kwɔːtәz/ |

main course |

/meIn ‘kɔʔs/ |

/meIŋ ‘kɔːs/ |

matched pairs |

/mæt∫t ‘pεːz/ |

/mæt∫ ‘pεːz/ |

perhaps |

/pә’hæps/ |

/præps/ |

Phonetic Conditioning

Phonetic conditioning is a term used to cover the way in which speech segments are influenced by adjacent (or near-adjacent) segments, causing phonemes to vary in their realisation according to the phonetic context. We can distinguish three main types: (1) allophonic variation; (2) assimilation; (3) elision.

Throughout the sections on English segments, we have discussed deviations from the target forms of phonemes. These result from phonetic conditioning and are responsible for much of any range of allophones occurring in complementary distribution. We shall now proceed to deal with the two other types of phonetic conditioning.

Where, as a result of phonetic conditioning, one phoneme is effectively replaced by a second under the influence of a third, we term the process assimilation.

Take the English word broadcast, which in careful pronunciation is /'brɔːdkɑːst/, but in connected speech may well become /'brɔːgkɑːst/. Here, one phoneme /d/ has been replaced by a second /g/ under the influence of a third /k/. This could be stated as a rule:

/d/ → /g/ before /k/

We can distinguish here the two forms of the word broad: (1) /brɔːd/, (2) /brɔːg/, where form (1) can be considered the ideal form, corresponding to the target that native speakers have in their minds. This is what is produced in the slowest and most careful styles of speech; it often bears a close resemblance to the spelling representation. Form (2), more typical of connected speech, is termed the assimilated form.

In many cases there is a two-way exchange of articulation features, e.g. English raise your glass /'reIz jɔː 'glaːs/ → /'reIƷ Ʒɔː 'glɑːs/. This is termed reciprocal assimilation.

Nasal and lateral assimilations occur in English, mainly affecting initial /ð/ in unstressed words, e.g.

Nasal assimilations are especially common in French, e.g. un demi /  dәmi/ → /

dәmi/ → / nmi/, on demande /

nmi/, on demande / dәm

dәm d/ → /

d/ → / nm

nm d/.

d/.

Assimilations of different types may occur simultaneously, e.g. behind you /bә’haIndjuː/ → /bә’haIndƷuː/. Here both place and manner assimilation affects /d/ and /j/ of the ideal form:

More than one phoneme may be affected by an assimilation, e.g. point-blank range /pɔInt blæŋk 'reIndƷ/ → /pɔImp blæŋk 'reIndƷ/.

A change from the ideal form in connected speech may involve the deletion of a phoneme, e.g. English tasteless /'teIstlәs/ → /'teIslәs/. The phoneme is said to be elided and the process is termed elision.

Frequently, assimilation processes also involve elision, e.g. English mind-boggling /'maIndbDglIŋ/ → /'maImbDglIŋ/.

We can distinguish between contemporary assimilation and elision vs. historical assimilation and elision processes. In contemporary assimilation/elision (using ‘contemporary’ in the sense of ‘present-day’), there is an ideal form. The assimilation (or elision) takes place only in a certain phonetic context and, in most cases, assimilation or elision is optional. Once the original ideal forms become extinct, and the assimilated/elided forms are fixed, we term such cases historical assimilation and elision, e.g. cupboard /'kΛbәd/, where the form */'kΛpbɔːd/ has died out. The ‘silent letters’ of English spelling provide frequent reminders of historical elision, e.g. talk, comb, know, could, gnome, whistle, wrong, iron. See Section C5 for a more general discussion on language change.

88

Go through two or three pages of one of the extracts in Section D and find more examples of ‘silent letters’ in English.

There is a tendency nowadays for some historical elisions and assimilations to revert to the original forms as a result of the influence of spelling. For instance, in modern NRP English, /t/ is frequently pronounced in often (formerly /'Dfәn/).

89

If you’re a native speaker, how do you pronounce the following words: always, falcon, historical, hotel, often, perhaps, towards, Wednesday? Do you know how your parents say these words? And what about your grandparents (or people of similar age)? See Section C5. (If you’re not a native speaker, ask an English-speaking friend.)

The converse of elision is liaison, i.e. the insertion of an extra sound in order to facilitate the articulation of a sequence. We have seen (Section B2) that accents of English can be divided into two groups according to /r/ distribution, namely rhotic accents where /r/ is pronounced in all contexts, as opposed to non-rhotic accents (like NRP) where /r/ is pronounced only preceding a vowel. In these latter varieties orthographic r is regularly restored as a link across word boundaries, e.g.

sooner /'suːnә/ |

sooner or later /'suːnә r ɔː ‘leItә/ |

sure /∫ɔː/ |

sure enough /'∫ɔː r I’nΛf/ |

This is termed linking r. With most speakers of non-rhotic English, it is also possible to hear linking r when there is no r in the spelling. This is termed intrusive r.

the sofa in the catalogue /ðә 'sәƱfә r In ðә 'kætәlDg/

my idea of heaven /maI aI'dIә r әv ‘hevәn/

we saw a film /wi 'sɔː r ә 'fIlm/

bourgeois immigrants /bƱәƷwɑː r 'ImIgrәnts/

via Australia /vaIә r D'streIliә/

Intrusive r is heard after the vowels /ɑː ɔː ә/ and the diphthongs terminating in /ә/. Instances with other vowels hardly ever occur: /εː/ is invariably spelt with r (except possibly in the word yeah as a form of yes); final /зː/ almost always has r in the spelling. Many native speakers are aware of the existence of intrusive r and many seem to make a conscious effort to avoid it (especially after /ɑː/ and /ɔː/). It is often considered by English people (particularly the older generation) as ‘lazy’ or ‘uneducated’ speech. Nevertheless, it is a characteristic feature of NRP, and is also heard from the overwhelming majority of those who use any non-rhotic variety of English. Some native speakers will insert a glottal stop in examples like those given above, in a conscious effort to avoid producing an /r/ link. But, interestingly, many of those who condemn intrusive r vociferously are unaware of the fact that they regularly use it themselves.

French is notable for an elaborate system of liaison, e.g. Il est assez intelligent, where ‘est’ and ‘assez’, pronounced /e/ and /ase/ in citation form, recover the final consonants when they occur pre-vocalically in connected speech: /il εt asεz  tεliƷ

tεliƷ /.

/.

Related to liaison is epenthesis, which is the insertion into a word of a segment which was previously absent. In all varieties of English, including NRP, speakers often insert a homorganic plosive between a nasal and a fricative in examples such as the following: once /wΛnts/, length /leŋkθ/, something /'sΛmpθIŋ/. As a result, words like sense and scents may be pronounced identically as /sents/.

90

Some English native speakers distinguish the following pairs. Others, pronouncing an epenthetic consonant, say them identically: mince – mints; prince – prints; patience – patients; chance – chants; tense – tents; Samson – Sampson; Thomson – Thompson. What do you do? Check with friends. Can you think of any other examples of the same phenomenon?

In some accents of English, particularly Irish English, an epenthetic /ә/ is inserted in sequences such as /lm/ and /rm/, e.g. film /'fIlәm/, alarm /ә’larәm/.

Assimilation and elision tend to be more frequent in:

unstressed rather than stressed syllables;

unstressed rather than stressed syllables;

rapid rather than slow tempo;

rapid rather than slow tempo;

informal rather than formal registers.

informal rather than formal registers.

Alveolar → Bilabial in Context Preceding Bilabial

footpath /'fƱppɑːθ/, madman /'mæbmәn/, pen pal /'pem pæl/, in March /Im ‘mɑːt∫/, runway /'rΛmweI/

Alveolar → Velar in Context Preceding Velar

gatecrash /'geIkkræ∫/, kid-gloves /kIg ‘glΛvz/, painkiller /'peIŋkIlә/

Note that in NRP the allophone of /p k/ representing orthographic t is almost invariably strongly pre-glottalised and never has audible release: [ʔp ʔk], e.g. footpath [‘fƱʔppɑːθ], gatecrash [‘geIʔkkræ∫]. Often there will be complete glottal replacement [‘fƱʔpɑːθ], [‘geIʔkræ∫].

Alveolar → Palato-Alveolar in Context Preceding Palato-Alveolar

spaceship /'speI∫∫Ip/, news sheet /'njuːƷ ∫iːt/

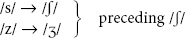

The plosives /t d/ merge regularly with you and your in a process of reciprocal assimilation of place and manner. The fricatives /s z/ have similar reciprocal assimilation with any word-initial /j/:

/t/ + /j/ → /t∫/

/d/ + /j/ → /dƷ/

/s/ + /j/ → /∫Ʒ/

/z/ + /j/ → /ƷƷ/

suit yourself /'suːt∫ɔː'self/, find your umbrella /'faIndƷɔː r Λm'brelә/

nice yellow shirt /'naI∫ 'ƷelәƱ '∫зːƱ/, where’s your cup? /'wεːƷ Ʒɔː 'kΛp/

Assimilations of this sort are especially common in tag-questions with you:

You didn’t do the washing, did you? /'dIdƷu/

You should contact the police, shouldn’t you? /'∫Ʊd t∫u/

t∫u/

Assimilation is also frequent in the phrase Do you. This is often written d’you in informal representations of dialogue: D’you come here often? /dƷu ‘kΛm hIә r ‘Df /.

/.

Initial /ð/ in unstressed words may be assimilated following /n l s z/:

on the shelves /Dn nә '∫elvz/, all the time /ɔːl lә 'taIm/, what’s the matter? /'wDts sә 'mætә/, how’s the patient? /haƱz zә 'peI∫ t/.

t/.

Lagging assimilations are most frequent preceding the. Nevertheless, a difference is still to be heard (except at very rapid tempo) between the and a as a result of the lengthening of the preceding segment and possible differences in rhythm. With words other than the, assimilation of this type is less frequent – though by no means uncommon – particularly in unstressed contexts.

in this context /In nIs 'kDntekst/, when they arrive /wen neI ә'raIv/, will they remember? /'wIl leI rә'membә/, was there any reason for it? /wәz zεː r 'eni 'riːz fɔː r It/.

fɔː r It/.

In English, energy assimilation is rare in stressed syllables. Two obligatory assimilations are used to and have to (where equivalent to ‘must’), e.g.

I used to play cricket /aI 'juːstә 'pleI 'krIkIt/, cf. I used two (main verb) /aI 'juːzd 'tuː/ I have to write him a letter /aI 'hæftә 'raIt Im ә ‘letә/, cf. I have two (main verb ‘possess’) /aI 'hæv 'tuː/

There are also some word-internal energy assimilations, generally with free variation between two possible forms:

newspaper /'njuːspeIpә/ or /'njuːzpeIpә/; absurd /әp’sзːd/, /әb’sзːd/ or /әb’zзːd/; absolute /'æpsәluːt/ or /'æbsәluːt/; absorb /әb’zɔːb/ or /әb’sɔːb/; obsession /әp’se∫ / or /әb’se∫

/ or /әb’se∫ /

/

Although energy assimilations across word boundaries are rare in stressed syllables, they do occur in unstressed contexts, but only in the form lenis to fortis. This is particularly true of final inflexional /z/ (derived from the s of plurals, possessives and verb forms), and also with function words such as as and of and auxiliary verbs:

of course /әf ‘kɔːs/, it was stated /It wәs ‘steItId/, as soon as possible /әs ‘suːn әs ‘pDsәb /, if she chooses to wait /If ∫i ‘t∫uːzIs tә ‘weIt/, my sister’s teacher /maI ‘sIstәs ‘tiːt∫ә/, the waiter’s forgotten us /ðә ‘weItәs fә’gDt

/, if she chooses to wait /If ∫i ‘t∫uːzIs tә ‘weIt/, my sister’s teacher /maI ‘sIstәs ‘tiːt∫ә/, the waiter’s forgotten us /ðә ‘weItәs fә’gDt Λs/

Λs/

Note that fortis to lenis assimilations, e.g. back door */bæg ‘dɔː/, not bad */nDd ‘bæd/) are not found in English. Such assimilations are common in many languages, e.g. French and Dutch.

Elision of /t/ or /d/ is common if they are central in a sequence of three consonants:

past tense /pɑːs 'tens/, ruined the market /'ruːIn ðә 'mɑːkIt/, left luggage /lef 'lΛgIdƷ/, failed test /feIl 'test/

Elisions such as these may remove the /t d/ marker of past tense in verbs but the tense is usually (not always) clear through context. Elision of /t d/ is not heard before /h/: smoked herring /'smәƱkt ‘herIŋ/. If /nt/ or /lt/ are followed by a consonant, there is normally no elision of /t/ (except at very rapid tempo), though /t/ will be glottally reinforced [ʔt] or replaced by [ʔ]. Note that the vowel before /nt/ and /lt/ is shortened: spent time /'spent ‘taIm/ [‘spenʔt ‘taIm] or [‘spenʔ ‘taIm]; Walt Disney /wɔːlt ‘dIzni/ [wɔlʔt ‘dIzni] or [wɔlʔ ‘dIzni]. Sequences of consonant + /t + j/ and consonant /d + j/ generally retain /t/ and /d/, but often have reciprocal assimilation to /t∫/ and /dƷ/:

I’ve booked your flight /aIv 'bƱkt∫ɔː 'flaIt/, I told your husband /aI 'tәƱldƷɔː 'hΛzbәnd/

The verb forms wouldn’t you, didn’t you, etc. are regularly heard with this assimilated form: /'wƱd t∫u, 'dId

t∫u, 'dId t∫u/ (see pp. 125–6).

t∫u/ (see pp. 125–6).

The sequence /skt/ has elision of /k/ instead of, or if preceding consonants, in addition to /t/:

masked gunman /mɑːst 'gΛnmәn/ or /'mɑːs 'gΛnmәn/, they asked us /ðeI 'ɑːst әs/

The following are examples of connected speech forms not covered by what has been stated already:

In more rapid speech, /v/ is sometimes elided before /m/ in the verbs give, have, leave: give me a chance /'gI mi ә 't∫ɑːns/, do you have my number /duː ju 'hæ maI 'nΛmbә/, leave me alone /'liː mi ә’lәƱn/.

91

Transcribe phonemically, showing intonation groups and sentence stress, and using weak and contracted forms wherever possible.

Transcription Passage 10

She tried to fancy what the flame of a candle looks like after the candle is blown out, since she could not remember ever having seen such a thing. After a while, finding that nothing more happened, she decided to go into the garden at once. But poor Alice! When she got to the door, she discovered that she had forgotten the little golden key, but when she went back to the table for it, she found she could not possibly reach it. Alice could see it quite plainly through the glass, and she tried her best to climb up one of the legs of the table, but it was too slippery. When she had tired herself out with trying, the poor little thing sat down and cried.