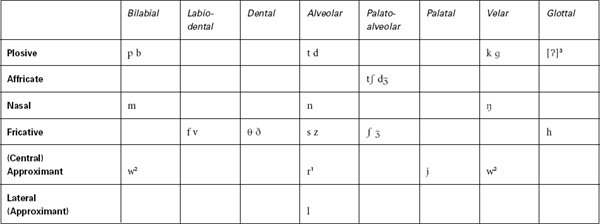

Table B2.1English consonant grid

Notes

1 /r/ is post-alveolar.

2 /w/ is labial-velar with two strictures (see Section A5).

3 In NRP [ʔ] is an allophone. Hence the square brackets.

We’ve already discussed the various possibilities for producing consonant sounds. Now we’re going to examine in greater detail how these sounds function in present-day English. It is usual to provide an overview in the form of a consonant grid with the following conventions: place on the horizontal axis, manner on the vertical axis; fortis precedes lenis in each pair.

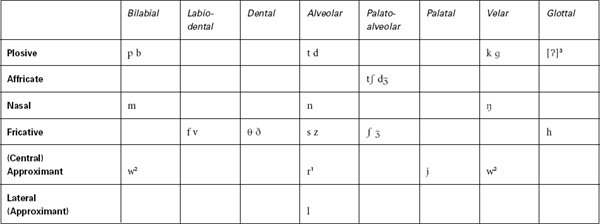

Table B2.1English consonant grid

Notes

1 /r/ is post-alveolar.

2 /w/ is labial-velar with two strictures (see Section A5).

3 In NRP [ʔ] is an allophone. Hence the square brackets.

The English stop phonemes (1) plosives /p t k b d g/ and (2) affricates /t∫ dƷ/ occur in initial, medial and final contexts.

Stops (i.e. plosives and affricates) have three stages:

in the approach stage, the articulators come together and form the closure;

in the approach stage, the articulators come together and form the closure;

in the hold stage, air is compressed behind the closure;

in the hold stage, air is compressed behind the closure;

in the release stage, the articulators part and the compressed air is released, either (1) rapidly with plosion in the case of plosives, or (2) slowly with friction in the case of affricates.

in the release stage, the articulators part and the compressed air is released, either (1) rapidly with plosion in the case of plosives, or (2) slowly with friction in the case of affricates.

See Figure B2.4 below.

In all cases a closure is made at some place in the vocal tract:

at the lips for bilabial /p b/ (Figure B2.1);

at the lips for bilabial /p b/ (Figure B2.1);

tongue-tip against alveolar ridge for alveolar /t d/ (Figure B2.2);

tongue-tip against alveolar ridge for alveolar /t d/ (Figure B2.2);

back of tongue against velum for velar /k g/ (Figure B2.3).

back of tongue against velum for velar /k g/ (Figure B2.3).

English has two phoneme affricates, namely /t∫/ and /dƷ/; see Section A5 (p. 44) for cross-section diagrams of /t∫ dƷ/. A closure is formed between a large area of the tip, blade and the front of the tongue with the rear of the alveolar ridge and the front of the hard palate. The palato-alveolar closure is released relatively slowly, thus producing friction at the same place of articulation (i.e. homorganic). Like the palato-alveolar fricatives /∫ Ʒ/, these affricates are strongly labialised, with trumpet-shaped lip-rounding. Fortis /t∫/ is energetically articulated (though without aspiration); lenis /dƷ/ is weaker and has potential voice.

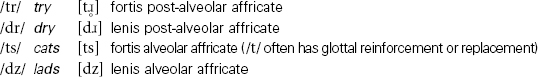

In addition there are the following phonetic affricates resulting from a sequence of two homorganic consonants:

Affrication is also heard from many speakers who produce bilabial affricates [pφ bβ] as realisations of the sequences /pf bv/, e.g. helpful, obvious.

The fortis stops /p t k t∫/ have energetic articulation and are voiceless; lenis stops /b d g dƷ/ have weaker articulation and have potential voice (see Section A5). In addition, aspiration (for plosives) and pre-glottalisation are important distinguishing features.

Aspiration (symbolised phonetically by [h]) occurs when fortis plosives /p t k/ are initial in a stressed syllable, and takes the form of a delay in the onset of voicing, an effect often compared to a little puff of air (see Figure B2.6). The link with stress is significant; in com'petitor [kәm’phetItә] aspiration is heard on the /p/, but much less so on the unstressed /k/ or the two /t/s; compare 'competent ['khDmpәtәnt]. In initial clusters with /s/, e.g. stool, spool, school, aspiration is absent. See below for devoicing of /l r j w/ following fortis plosives.

72 (Answers on Website)

A test for aspiration is to put a feather or a piece of paper in front of your mouth and then pronounce the consonants [p t k]. If you’re a native speaker of English, the paper should move noticeably.

Try the same test with the lenis non-aspirated [b d g]. The paper should move less or not at all. Now try the clusters [sp st sk] as in spy, sty, sky. Does the paper move now?

Aspiration is a feature of most English accents (a few varieties, e.g. some Lancashire, and most Scottish and South African English, have very weakly aspirated stops). Languages split into two main groups:

those with aspiration, such as English, standard German, the Scandinavian languages

those with aspiration, such as English, standard German, the Scandinavian languages

(Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic), Welsh, Chinese; q those without aspiration, such as Dutch, southern varieties of German, the Romance languages (e.g. French, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Rumanian) and the Slavonic languages (e.g. Russian, Polish, Czech, Slovak, Serbian, Croatian and Slovene).

(Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic), Welsh, Chinese; q those without aspiration, such as Dutch, southern varieties of German, the Romance languages (e.g. French, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Rumanian) and the Slavonic languages (e.g. Russian, Polish, Czech, Slovak, Serbian, Croatian and Slovene).

Some languages (e.g. Korean) distinguish voiceless vs. aspirated voiceless vs. voiced stops; many Indian languages have a four-term distinction (voiceless vs. aspirated voiceless vs. voiced vs. aspirated voiced). Non-aspiration languages tend to have firmer closures for voiceless plosives; the articulators form a tight, efficient valve, with a brisk release of the compressed air. Aspirated articulations have looser closures which act like an inefficient ‘leaky’ valve from which the air is released somewhat more slowly.

English syllable-final fortis stops are accompanied by a reinforcing glottal stop at or before the hold stage. Termed (pre-)glottalisation, or glottal reinforcement, this is one of the most significant phonetic markers of final fortis stops in many English accents. In NRP the pattern of glottal reinforcement is as follows.

Syllable-final fortis stops are regularly glottalised before another consonant, e.g. I don’t like that fat guy [aI 'dәƱnʔt laIʔk 'ðæʔt 'fæʔt 'gaI], sleepwalker ['sliːʔpwɔːkә], locksmith ['lDʔksmIθ], watchdog ['wDʔt∫dDg]. Note that /t∫/ also has optional glottalisation in medial position, e.g. kitchen ['kIʔt∫In].

Syllable-final fortis stops are regularly glottalised before another consonant, e.g. I don’t like that fat guy [aI 'dәƱnʔt laIʔk 'ðæʔt 'fæʔt 'gaI], sleepwalker ['sliːʔpwɔːkә], locksmith ['lDʔksmIθ], watchdog ['wDʔt∫dDg]. Note that /t∫/ also has optional glottalisation in medial position, e.g. kitchen ['kIʔt∫In].

In the following contexts both glottalised and non-glottalised forms are to be found:

In the following contexts both glottalised and non-glottalised forms are to be found:

The most frequently glottalised consonant is /t/. In particular, pre-glottalisation (and glottal replacement, see below) very commonly affects a small group of high-frequency words, namely: it, bit, get, let, at, that, got, lot, not (and contracted forms: don’t, can’t, aren’t, isn’t, etc.), what, put, but, might, right, quite, out, about.

The most frequently glottalised consonant is /t/. In particular, pre-glottalisation (and glottal replacement, see below) very commonly affects a small group of high-frequency words, namely: it, bit, get, let, at, that, got, lot, not (and contracted forms: don’t, can’t, aren’t, isn’t, etc.), what, put, but, might, right, quite, out, about.

73

If you’re a native English speaker, do you glottalise the underlined stop consonant in any of these words or phrases? If you’re a non-native, try using pre-glottalisation with the stop closures in these examples.

not true; put right; it’s got twisted; tra door; atlas; pot luck.

door; atlas; pot luck.

Glottal replacement (an effect also known as ‘glottalling’) occurs when [ʔ] is substituted for /t/ so that, for example, shortbread, shorten, sit down are realised as ['∫ɔːʔbred, '∫ɔːʔ , sIʔ 'daƱn]. This may also occur where /p k/ are followed by a homorganic stop or nasal, e.g. stepbrother ['steʔ brΛðә], took care ['tƱʔ 'kεː].

, sIʔ 'daƱn]. This may also occur where /p k/ are followed by a homorganic stop or nasal, e.g. stepbrother ['steʔ brΛðә], took care ['tƱʔ 'kεː].

Types of Release

When a plosive is followed by a homorganic nasal, the closure is not released in the usual way. Instead, the soft palate lowers, which allows the airstream to pass out through the nasal cavity; this is termed nasal release, e.g. submit, partner. Nasal release of /t d/ is also heard in final /tn dn/ leading into a syllabic nasal, e.g. shorten ['∫ɔːt ], rodent ['rәƱd

], rodent ['rәƱd t]. With fortis plosives, there is typically accompanying glottalisation, e.g. witness ['wIʔtnәs], help me ['helʔp mi]. In present-day NRP, fortis plosives normally undergo glottal replacement in this context, e.g. ['wIʔnәs ‘helʔ mi]. German is notable for the common occurrence of nasal release giving rise to syllabic nasals (often with assimilation: see Section B5), e.g. leben ‘to live’ ['leʔb

t]. With fortis plosives, there is typically accompanying glottalisation, e.g. witness ['wIʔtnәs], help me ['helʔp mi]. In present-day NRP, fortis plosives normally undergo glottal replacement in this context, e.g. ['wIʔnәs ‘helʔ mi]. German is notable for the common occurrence of nasal release giving rise to syllabic nasals (often with assimilation: see Section B5), e.g. leben ‘to live’ ['leʔb ], beten ‘to pray’ ['beːt

], beten ‘to pray’ ['beːt ], sagen ‘to say’ ['zaːg

], sagen ‘to say’ ['zaːg ].

].

In English, /t/ and /d/ can have lateral release, i.e. the alveolar closure is released by lowering the sides of the tongue, e.g. settle, partly, muddle, paddling. Following /t/, there is initial devoicing of /l/: ['set l], ['pɑːt

l], ['pɑːt li]. Similar tongue-side lowering is found in the sequences /kl gl pl bl/, as in prickly, struggling, grappling, bubbly, where the tongue takes up the alveolar position for /l/ during the hold stage of the stop.

li]. Similar tongue-side lowering is found in the sequences /kl gl pl bl/, as in prickly, struggling, grappling, bubbly, where the tongue takes up the alveolar position for /l/ during the hold stage of the stop.

Lateral release in NRP English often leads into syllabic laterals. In many other accents, lateral release is lacking and instead a vowel /ә/ or /Ʊ/ is inserted, giving e.g. settle ['setәl] or ['setƱl]. Of late, possibly as a result of the spread of London influence, realisations without lateral release have become increasingly common among younger NRP speakers. As opposed to what happens with syllabic /n/, glottalisation is not found in NRP in this context.

Sequences such as, for example, /pt gb kd gt∫ dg/, as in stopped, rugby, back door, big cheese, bad guys, where a plosive consonant is immediately followed by a stop, are termed overlapping stops. In such cases, the plosive has inaudible release and the second stop has inaudible approach.

74

Take a paragraph from any of the extracts in Section D and underline all the examples of overlapping stops that you can find. Then transcribe them phonemically.

In English, in a sequence of three stops, the central consonant (usually alveolar /t/ or /d/) lacks both audible approach and release stages. In fact, /t d/ in this context are elided in all but ultra-careful speech, e.g. clubbed together /'klΛb tә'geðә/, she looked quite young /∫i 'lƱk kwaIt 'jΛŋ/ (see Section B5 on elision).

Sequences of homorganic stops result in a single articulation with a prolonged hold stage, e.g. /gg/ (phonetically [gː]) as in big game. Where the first of such a homorganic sequence is fortis, the stop typically has glottal replacement, e.g. short time ['∫ɔːʔ 'taIm], great day ['greIʔ 'deI].

Alveolar /t d/ have a wide range of variation in NRP. Intervocalic /t/ (i.e. /t/ between vowels) is frequently realised as a very brief voiced stop which can be shown as [ ], e.g. British, pretty, but I, pathetic, that I. This effect is known as t-voicing and is particularly common in high-frequency words and expressions. The brevity of the tap and the shortening of the preceding vowel serve to maintain the contrast with /d/. Unlike American English, there is no tendency to neutralise the contrast /t – d/ in pairs such as clouted – clouded, writing – riding, waiter – wader. (See Section C1.)

], e.g. British, pretty, but I, pathetic, that I. This effect is known as t-voicing and is particularly common in high-frequency words and expressions. The brevity of the tap and the shortening of the preceding vowel serve to maintain the contrast with /d/. Unlike American English, there is no tendency to neutralise the contrast /t – d/ in pairs such as clouted – clouded, writing – riding, waiter – wader. (See Section C1.)

75

Are you a ‘t-voicer’? Say the following words and phrases and ask others in your class to judge.

better; phonetics; pretty; later; apathetic; not a lot of; what a pity; quite a lot.

If you do voice /t/, do you think the resulting sound is the same as /d/ or different? Check by saying pairs like whiter – wider, waiter – wader. Do you also extend t-voicing to contexts before syllabic /l/, e.g. bottle, total? Or do you replace /t/ here by glottal stop?

The bilabial and alveolar nasals /m n/ occur in all contexts, but velar /ŋ/ occurs only syllable-finally following checked vowels. For all three nasals, the place and manner of articulation is similar to that of the corresponding stops /b d g/ (see above). However, the soft palate is lowered (i.e. there is no velic closure; see Section A4), thus adding the resonance of the nasal cavity. See Figures B2.8, B2.9 and B2.10 for /m n ŋ/.

The soft palate anticipates the action of other articulators, and consequently vowels are nasalised preceding nasals, e.g. farm [f ːm], lawn [l

ːm], lawn [l ːn], gang [g

ːn], gang [g ŋ]. This tendency can be very noticeable in certain varieties, e.g. most American English.

ŋ]. This tendency can be very noticeable in certain varieties, e.g. most American English.

76

You may have noticed that when you have a cold, your nose gets blocked and nasals come out as non-nasals. Try saying the following text substituting non-nasal stops [b d g] for the nasals [m n ŋ].

Good morning, Mr Armstrong. I’m most sorry but I’m not coming in this afternoon owing to an appalling attack of influenza. I’m going to remain at home but with any luck, I’ll be in again on Wednesday morning. End of message.

gƱd 'bɔːdIg | bIstә r 'ɑːbstrDg || aIb 'bәƱst 'sDri bәt aIb 'dDt 'kΛbIg 'Id ðIs ɑːftә'duːd || 'әƱIg tu әd ә'pɔːlIg ә'tæk әv Idflu'edzә || aIb 'gәƱIg tә rә'beId әt 'hәƱb | bәt wIð 'edi 'lΛk | aIl bi 'Id ә'ged Dd 'wedzdeI 'bɔːdIg || 'ed әv 'besIdƷ ||

(A useful technique if you want a good excuse for staying away from work!)

All fricatives, except /h/, occur in fortis/lenis pairs. (Return to Sections A2 and A5 if you’re unsure of the contrast between lenis and fortis consonants.)

The lower lip makes near contact with the upper front teeth resulting in labio-dental friction. Lenis /v/ has potential voice.

The tongue-tip makes near contact with the rear of the upper teeth resulting in dental friction. Lenis /ð/ has potential voice, and often has the tongue withdrawn, being realised as a type of weak dental approximant.

Initial /ð/ occurs only in the following function words: the, this, that, these, those, then, than, thus, there, they, their, them; also in thence and the archaic words thou, thee, thy, thine, thither.

The tip/blade of the tongue makes near contact with the alveolar ridge. Air is channelled along a deep groove in the tongue, producing alveolar friction characterised by sharp hiss (see Figure B2.14). /s z/ are sometimes termed grooved fricatives; see Figure B2.13. Lenis /z/ has potential voice.

A large portion of the tongue (tip/blade/front) makes near contact with the alveolar ridge and the front of the hard palate. The airstream is channelled through a shallower groove than for /s z/. In addition, /∫ Ʒ/ have strong trumpet-shaped lip-rounding similar to that of /t∫ dƷ/. The resulting hiss is graver (i.e. lower pitched) than that of /s z/.

/Ʒ/ is notably restricted in its distribution, occurring mainly in medial position, e.g. usual, pleasure, etc. In initial and final position it is found only in recent French loanwords, e.g. genre, beige. In most of these cases, there are alternative pronunciations with /dƷ/. Remember that in initial clusters /pl kl/ in stressed syllables, e.g. clean, please, /l/ is devoiced and fricative [k iːn p

iːn p iːz] (see pp. 54–5).

iːz] (see pp. 54–5).

Phonetically, /h/ is like a voiceless vowel. The articulators are in the position for the following vowel sound and a strong airstream produces friction not only at the glottis but also throughout the vocal tract. Consequently, there are as many articulations of /h/ as there are vowels in English (and for that reason no cross-section diagram is provided). In English, /h/ occurs only preceding vowels.

The tip and blade of the tongue form a central closure with the alveolar ridge, while the sides of the tongue remain lowered. The airstream escapes over the lowered sides.

Clear l occurs before vowels, e.g. leap, and before /j/, as in value. The tongue shape is slightly palatalised with a convex upper surface giving a close front vowel [i]-type resonance (see Figure B2.16 below).

Dark l occurs before consonants and pause. The articulation is slightly velarised (see Section A5), with a concave upper surface, giving a back-central vowel [Ʊ]-type resonance, e.g. still [stIɫ], help [heɫp]. Dark l is often a syllable-bearer, when it will be of longer duration [ɫː], e.g. hospital /'hDspIt / [‘hDspItɫː]. Younger NRP speakers, especially those brought up in the area of London or the south-east, nowadays regularly have a vocalic dark l sounding rather like [Ʊ], especially following central and back vowels, e.g. doll [dDƱ], pearl [pзːƱ]. This effect is termed l-vocalisation. Traditional RP speakers tend to stigmatise this feature, which is nevertheless one of the striking changes going on in present-day English.

/ [‘hDspItɫː]. Younger NRP speakers, especially those brought up in the area of London or the south-east, nowadays regularly have a vocalic dark l sounding rather like [Ʊ], especially following central and back vowels, e.g. doll [dDƱ], pearl [pзːƱ]. This effect is termed l-vocalisation. Traditional RP speakers tend to stigmatise this feature, which is nevertheless one of the striking changes going on in present-day English.

The allophonic distribution of clear and dark l quoted above is true of NRP and most varieties of English, but other English accents show different patterns. For example, most Welsh and Irish accents have only clear l in all contexts, while many Scottish and American varieties have only dark l.

77

Try saying the following sentences (1) with dark l only, (2) with clear l only:

I’m told that this model will only be available for a little while longer.

Lesley feels awfully guilty putting you to all this trouble.

Delia’s told me she’ll call round at twelve.

The sides of the tongue are raised and in contact with the back teeth; the tongue-tip may move towards the rear of the alveolar ridge in a stricture of open approximation (see Figure B2.17 below). Although /r/ is classed as post-alveolar, the raising of the sides of the tongue is probably more important than the tongue-tip movement. The latter is in fact absent for many individuals. Most NRP speakers have accompanying labialisation, i.e. lip-rounding and protrusion.

The sporadic occurrence in times past of an alveolar tap [ ] in traditional RP in intervocalic contexts, e.g. borrow, marry, has been mentioned in Section A5. Nowadays, tap [

] in traditional RP in intervocalic contexts, e.g. borrow, marry, has been mentioned in Section A5. Nowadays, tap [ ] is rarely heard from NRP speakers although it is found in many regional accents. Curiously, it is still taught by elocutionists as ‘correct speech’. Another recent development is that some young speakers (especially in the south-east of England) use a labio-dental approximant, symbolised as [υ]. People often use the pejorative term ‘defective r’ for this pronunciation, and it’s sometimes imitated for comic effect. Consequently, even though it’s increasingly heard from young speakers, it’s not recommended for imitation by non-natives.

] is rarely heard from NRP speakers although it is found in many regional accents. Curiously, it is still taught by elocutionists as ‘correct speech’. Another recent development is that some young speakers (especially in the south-east of England) use a labio-dental approximant, symbolised as [υ]. People often use the pejorative term ‘defective r’ for this pronunciation, and it’s sometimes imitated for comic effect. Consequently, even though it’s increasingly heard from young speakers, it’s not recommended for imitation by non-natives.

A very significant feature of English is the split of accents into two groups according to /r/ distribution. In rhotic varieties, /r/ is pronounced in all contexts. Rhotic speech comprises most American varieties – including General American and Canadian – Scottish, Irish, much Caribbean, and the regional accents of the West Country of England. In non-rhotic varieties, /r/ is pronounced only before a vowel. Non-rhotic speech includes most of England and Wales, much American English spoken in the southern and eastern states, some Caribbean, all Australian, all South African, and most New Zealand varieties of English. Note that English as spoken by most African Americans from all areas of the USA is typically non-rhotic.

In non-rhotic varieties, /r/ is generally pronounced across word boundaries, e.g.

This type of liaison is termed linking r. See Section B5 for further discussion of this and other types of r-liaison.

78

Go round your class and discover who has a rhotic form of English. If they’re native speakers, which part of the English-speaking world do they come from? If they’re non-natives, which type of English are they imitating?

The palatal approximant /j/ is a brief [i]-vowel-like glide (Figure B2.18). In NRP, the sequences /tj dj/ are typically replaced by palato-alveolar affricates /t∫ dƷ/ not only within the word (e.g. module /'mDdƷuːl/) but also across word boundaries, particularly involving you, your, e.g. can’t you /'kɑːnt∫u/, did you /'dIdƷu/, mind your own business /'maIndƷɔː r әƱn ‘bIznәs/. It is also nowadays the most frequent pronunciation initially in stressed syllables, e.g. Tuesday /'t∫uːzdeI/, induce /In'dƷuːs/. Such forms, which were formerly not accepted in traditional RP, are still stigmatised by some members of the older generation as ‘lazy speech’. A notable difference between British and American accents is the frequent loss of /j/ after the alveolar consonants /t d n/ in most American English. This effect is termed yod-dropping. See also p. 158.

79

In your English idiolect, are the beginnings of these words the same or different?

chews – Tuesday; choose – tune; Jew – due; June – dune; jukebox – duke; jewel – dual.

So do you say, for example, tune /tjuːn/, /t∫uːn/ or /tuːn/? And is duke /djuːk/, /dƷuːk/ or /duːk/? Ask round the class and compare results for all the words.

For /w/ there are two strictures of open approximation: (1) labial and (2) velar. Like /j/, /w/ is like a brief vowel glide. The [u]-like glide has strong lip-rounding.

A few speakers will strive to produce an additional phoneme contrast, with a voiceless labial-velar fricative, symbolised as /w/, used in all words beginning wh, e.g. where – wear /wεː – wεː/. Those who produce this sound have often undergone speech training of some kind. Over-correct forms are not infrequently encountered. These two examples were actually heard from BBC announcers:

Isle of Wight |

*/aIl әv 'waIt/ |

the ways of the world |

*/ðә ‘weIz әv ðә ‘wзːld/ |

It is probable that the phoneme /w/ was extinct in the everyday language of England by the eighteenth century. But it is somewhat more often heard in American English, and is still a living feature of all Scottish varieties and also much Irish English.

80

Do you have any English-speaking friends or relatives who say /w/ for wh? If so, is it natural to them or were they taught to say it in school, or by a speech trainer in elocution classes?

All nasals are typically voiced throughout and there is none of the devoicing characteristic of the fricatives and stops. Only when following /s/ in initial clusters are /m n/ partially devoiced [

], e.g. smoke [s

], e.g. smoke [s әƱk], snow [s

әƱk], snow [s әƱ].

әƱ].

Similarly, /l/ is also typically voiced, not showing initial and final devoicing. It is, however, devoiced and fricative [ ] in initial clusters following the voiceless plosives /p k/ in stressed syllables, e.g. plain, claim [p

] in initial clusters following the voiceless plosives /p k/ in stressed syllables, e.g. plain, claim [p eIn k

eIn k eIm]. (The cluster /tl/ does not occur in initial position.) The same holds true for /w j/, e.g. queen, cute /k

eIm]. (The cluster /tl/ does not occur in initial position.) The same holds true for /w j/, e.g. queen, cute /k Iːn k

Iːn k uːt/. This effect corresponds to the aspiration of the fortis plosives found in other contexts.

uːt/. This effect corresponds to the aspiration of the fortis plosives found in other contexts.

In stressed syllable-initial clusters, a completely devoiced post-alveolar fricative [ ] is realised following fortis plosives /p k/, e.g. price, crease. In the sequence /pr/, bilabial friction may be heard. The sequences /tr dr/, e.g. troop, droop, are realised as post-alveolar affricates, [t

] is realised following fortis plosives /p k/, e.g. price, crease. In the sequence /pr/, bilabial friction may be heard. The sequences /tr dr/, e.g. troop, droop, are realised as post-alveolar affricates, [t d

d ] (see p. 95).

] (see p. 95).

Preceding /j/, plosives are palatalised [pj bj tj dj kj gj], e.g. pure, beauty, tune, dune, cure, angular. As stated above, the sequences /tj dj/ are frequently reduced in NRP to /t∫ dƷ/, so giving no contrast between words like juice and deuce, chewed and the first syllable of Tudor. After fortis consonants, /j/ is devoiced and fricative [ ], e.g. pure, tuna, cue; it may be realised as a voiceless palatal fricative [ç] (similar to the sound known in German as the ich-Laut, in words like ich ‘I’, Bücher ‘books’). The sequence /hj/ in huge, human is also frequently realised in this way [ç], e.g. humid /hjuːmId/ [çuːmId].

], e.g. pure, tuna, cue; it may be realised as a voiceless palatal fricative [ç] (similar to the sound known in German as the ich-Laut, in words like ich ‘I’, Bücher ‘books’). The sequence /hj/ in huge, human is also frequently realised in this way [ç], e.g. humid /hjuːmId/ [çuːmId].

Other fricatives preceding /j/ are also palatalised, e.g. fuse, views, assume, presume. Following word-initial /s/, NRP deletes traditional /j/, e.g. suit, suicide (at one time /sjuːt ‘sjuːIsaId/, nowadays typically /suːt ‘suːIsaId/). These well-established forms nevertheless occasionally suffer criticism from some older-generation speakers.

Before /j/ and /Iә/, the nasals /m n/ are strongly palatalised, e.g. mute [mjjuːt], near [njIә].

Consonants preceding /w/ are strongly labialised, e.g. switch [swwIt∫], language [‘læŋgwwIdƷ]. Following the fortis alveolar and velar plosives /t k/, as in entwine, quick, /w/ is in addition devoiced, [Intw aIn], [kw

aIn], [kw Ik]; the remaining voiceless plosive /p/ is not found in this context. Note that the friction for [

Ik]; the remaining voiceless plosive /p/ is not found in this context. Note that the friction for [ ] in this case is bilabial and not velar.

] in this case is bilabial and not velar.

Consonants may be advanced or retracted, dependent on the phonetic context. Alveolar consonants are particularly prone to place variation. The plosives /t d/ are advanced to dental when adjacent to dental fricatives (shown by means of the diacritic [ ] below the symbol), i.e. articulated with the tongue-tip behind the teeth: [

] below the symbol), i.e. articulated with the tongue-tip behind the teeth: [

] in eighth, hid them. The same goes for /n l/ [

] in eighth, hid them. The same goes for /n l/ [

], e.g. anthem, both numbers, healthy, faithless.

], e.g. anthem, both numbers, healthy, faithless.

For /k g/, the velar closure is advanced before front vowels and /j/ – an effect shown in phonetic transcription by the diacritic [+], e.g. key, cue [k+iː k+juː]. The closure is retracted before back vowels (shown by [-]), cf. corn, cob [k-ɔːn k-Db]. If you insert a finger into your mouth, you can feel the difference between the two /k/ allophones quite easily.

Before labio-dental /f v/, both /m/ and /n/ may be realised as labio-dental nasal [ɱ], e.g. in front; thus, despite the spelling, the consonant clusters in emphasis and infant are normally pronounced identically.

81

Transcribe phonemically, showing intonation groups and sentence stress, and using weak and contracted forms wherever possible.

Transcription Passage 8

‘No, I’ll look first,’ she said, ‘and see whether it’s marked “poison” or not’, because she had read several nice little stories about children who had got burnt, and eaten up by wild beasts, and other unpleasant things, all because they would not remember the simple rules their friends had taught them. For instance, a red-hot poker will burn you if you hold it too long. If you cut your finger very deeply with a knife, it usually bleeds. Alice had never forgotten that if you drink much from a bottle marked ‘poison’, it is almost certain to disagree with you, sooner or later.