Northern English lacks the contrast /λ − Ʊ/ in STRUT/FOOT; such varieties have no phoneme /λ/ as found in other types of English.

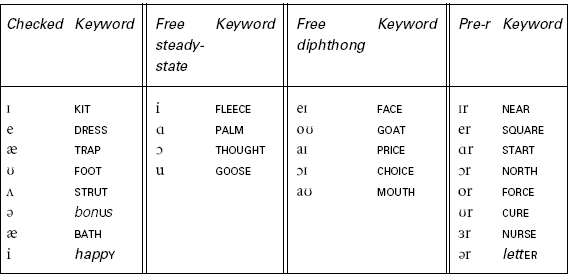

Northern English lacks the contrast /λ − Ʊ/ in STRUT/FOOT; such varieties have no phoneme /λ/ as found in other types of English.The basic set of NRP reference vowels (p. 16) is not adequate to deal with all the features encountered in other English varieties. For this purpose, we’ve used five additional keywords: BATH, JUICE, FORCE, NORTH, happy. Our full list of keywords is printed in Table C1.1.

It has become common practice to classify pronunciation variation between accents along the following lines (cf. Wells 1982: 72–80).

Systemic variation: where one accent possesses more or fewer phonemes than another accent in a particular part of the sound system.

Northern English lacks the contrast /λ − Ʊ/ in STRUT/FOOT; such varieties have no phoneme /λ/ as found in other types of English.

Northern English lacks the contrast /λ − Ʊ/ in STRUT/FOOT; such varieties have no phoneme /λ/ as found in other types of English.

South Wales English has an additional contrast in GOOSE/JUICE with an extra phoneme /Iu/ not found in other accents.

South Wales English has an additional contrast in GOOSE/JUICE with an extra phoneme /Iu/ not found in other accents.

Scottish, Irish and some General American have an extra /M − W/ contrast: e.g. which – witch.

Scottish, Irish and some General American have an extra /M − W/ contrast: e.g. which – witch.

Distributional variation accounts for cases where two accents may have the same system but where environments in which a particular phoneme may occur differ. Note that distributional variation is not restricted to a particular set of words but operates ‘across the board’ as an integral part of the phonological system of the accents concerned. There are (in principle) no exceptions to the rule.

Examples of distributional variation are:

In rhotic accents (see Section B2), r is pronounced wherever it occurs in the spelling. In non-rhotic accents, it is pronounced only before a vowel.

In rhotic accents (see Section B2), r is pronounced wherever it occurs in the spelling. In non-rhotic accents, it is pronounced only before a vowel.

In the happy words, e.g. happy, pretty, Julie, committee, etc., Scots, Northern Ireland, Yorkshire, Lancashire (except Merseyside) and traditional RP select KIT; most other accents (e.g. London, Birmingham, General American, Australian and most NRP) select FLEECE.

In the happy words, e.g. happy, pretty, Julie, committee, etc., Scots, Northern Ireland, Yorkshire, Lancashire (except Merseyside) and traditional RP select KIT; most other accents (e.g. London, Birmingham, General American, Australian and most NRP) select FLEECE.

Table C1.1Keywords for reference vowels

KIT |

FLEECE |

FACE |

DRESS |

SQUARE |

GOAT |

TRAP |

PALM |

PRICE |

LOT |

THOUGHT |

MOUTH |

STRUT |

NURSE |

CHOICE |

FOOT |

GOOSE |

NEAR |

BATH |

JUICE |

CURE |

bonUs |

NORTH |

|

happY |

FORCE |

|

Source: Table adapted from Wells (1982: 120); the keyword JUICE is additional to Wells’s categorisation.

Lexical variation: where the phoneme chosen for a word or a specific set of words is different in one accent as compared with another. This can affect either a very large group of words (such as our first two examples below), or a very small group (as in our third example).

In the BATH words, e.g. bath, pass, dance, etc. (see Section B3), northern England and Midland accents generally select the TRAP vowel; so do most other varieties worldwide, e.g. American. Cockney and NRP, however, select the PALM vowel. Australians vary.

In the BATH words, e.g. bath, pass, dance, etc. (see Section B3), northern England and Midland accents generally select the TRAP vowel; so do most other varieties worldwide, e.g. American. Cockney and NRP, however, select the PALM vowel. Australians vary.

In words spelt or, most varieties of English select the THOUGHT vowel. However, some accents retain what was formerly a widespread distinction between two groups known as the FORCE and NORTH words. The FORCE category contains words like force, store, sport and also hoarse, course spelt with an extra letter. The NORTH words include north, cork, absorb, horse. The manner in which these groups are differentiated varies, but in Scottish English, for example, FORCE words have the GOAT vowel while NORTH words have the same vowel as in THOUGHT, giving /fors/ and /nɔrθ/.

In words spelt or, most varieties of English select the THOUGHT vowel. However, some accents retain what was formerly a widespread distinction between two groups known as the FORCE and NORTH words. The FORCE category contains words like force, store, sport and also hoarse, course spelt with an extra letter. The NORTH words include north, cork, absorb, horse. The manner in which these groups are differentiated varies, but in Scottish English, for example, FORCE words have the GOAT vowel while NORTH words have the same vowel as in THOUGHT, giving /fors/ and /nɔrθ/.

In parts of Lancashire, words spelt -ook such as book, took, look have the GOOSE vowel. In other English varieties, GOOSE only occurs in a few examples of this type (e.g. snooker, spook). Otherwise FOOT is found.

In parts of Lancashire, words spelt -ook such as book, took, look have the GOOSE vowel. In other English varieties, GOOSE only occurs in a few examples of this type (e.g. snooker, spook). Otherwise FOOT is found.

There is no easy way of predicting which words will be susceptible to lexical variation. Furthermore, speech habits may vary within one accent. For example, NRP speakers vary in their choice of vowel for orthographic o in words such as constable, accomplish. Most people use the STRUT vowel, but some choose LOT. Note that the distinction between lexical and distributional variation is not always clear-cut. A good example of this is the case of yod-dropping in American varieties (see p. 158). Even though we have classed this as an example of distributional variation, as it is in principle possible to state a clear rule for the occurrence of this feature, there is in fact much variation on an individual speaker level.

Realisational variation: all variation which is not covered by any of the categories above will relate to the realisation of phonemes:

FACE and GOAT are narrow diphthongs or steady-state vowels in Scots, Irish, Welsh and northern English accents, but wide diphthongs in Cockney, Birmingham, Australian, New Zealand and most of the accents of the southern USA.

FACE and GOAT are narrow diphthongs or steady-state vowels in Scots, Irish, Welsh and northern English accents, but wide diphthongs in Cockney, Birmingham, Australian, New Zealand and most of the accents of the southern USA.

Initial /p t k / are aspirated in most accents (including NRP and General American) but are unaspirated in Lancashire, South African and most Indian English.

Initial /p t k / are aspirated in most accents (including NRP and General American) but are unaspirated in Lancashire, South African and most Indian English.

Once again, some realisational variation will occur even within a specific accent. Notoriously, even within NRP, glottalisation varies tremendously, as do realisations of vowels such as GOAT and GOOSE.

Patterns of realisational variation often affect more than one phoneme in similar ways, as is the case with both examples above. Such variation frequently shows interesting patterning, for instance in the symmetry of the vowel system, or modifications to articulations determined by specific phonetic contexts which affect a whole range of consonant or vowel phonemes.

In our brief overview of General American (as compared with NRP) below, we mention all four types of variation.1 Systemic, distributional and lexical variation are structurally the most significant types, since in their different ways they involve phonemic change. Realisational variation (the commonest type, but less significant since it involves no phonemic change) is regarded as the default.

In this and the following sections we are going to discuss some of the important varieties of English spoken worldwide. We shall begin with a comparison of the two major models of English – British NRP and General American. Although we shall be concentrating here on the differences between these two varieties, in fact they are most notable for their great similarity. It may be worth emphasising again (see Section A1) that educated British and American speakers communicate with ease, and rarely experience any problems in understanding each other’s pronunciation.

The consonant system of General American is in essentials the same as that of British accents and can be represented with the same phonemic symbols. Note, however, the following differences.

]. Normally /t/ is realised in intervocalic position as a brief voiced tap when /t/ follows a stressed vowel, both word-medially and also across word boundaries, e.g. heating, I hate it /'hi

]. Normally /t/ is realised in intervocalic position as a brief voiced tap when /t/ follows a stressed vowel, both word-medially and also across word boundaries, e.g. heating, I hate it /'hi Iŋ, aI 'heI

Iŋ, aI 'heI It/. This is also true if /r/ intervenes, e.g. party /'par

It/. This is also true if /r/ intervenes, e.g. party /'par i/, and before syllabic /

i/, and before syllabic /

/, e.g. metal /'me

/, e.g. metal /'me

/, traitor /'treIː

/, traitor /'treIː

/. Note that in GA (and in American English generally), t-voicing typically leads to neutralisation of the contrast /t – d/, so that heating – heeding and hit it – hid it sound the same. Although we are dealing here with an allophone of /t/ and not a phoneme, nevertheless, because of its high frequency in American English, it is normal to show it in slant brackets (distributional variation). Medial /nt/ is regularly reduced to /n/, e.g. winter /'wIn

/. Note that in GA (and in American English generally), t-voicing typically leads to neutralisation of the contrast /t – d/, so that heating – heeding and hit it – hid it sound the same. Although we are dealing here with an allophone of /t/ and not a phoneme, nevertheless, because of its high frequency in American English, it is normal to show it in slant brackets (distributional variation). Medial /nt/ is regularly reduced to /n/, e.g. winter /'wIn /. Word-final /t/ often lacks any audible release.

/. Word-final /t/ often lacks any audible release.GA (normal form) |

NRP (normal form) |

enthusiastic /InθuzI'æstIk/ |

/inθjuːzI'æstIk/ |

assume /ə'sum/ |

/ə'sjuːm/ |

presume /prə'zum/ |

/prə'zjuːm/ |

Table C1.2The vowels of General American

Notes

NORTH and FORCE are usually both NORTH (see p. 157 and p. 160, no. 10) PALM and THOUGHT may both be PALM

]. To British ears the initial [ɫ] can sometimes sound similar to /w/, so that life sounds rather like wife (realisational variation).

]. To British ears the initial [ɫ] can sometimes sound similar to /w/, so that life sounds rather like wife (realisational variation).Compared with the consonants, there is less similarity between the vowel systems of GA and NRP. Nevertheless, for the most part we can employ the same symbols. For GA varieties, the ‘length mark’ for free vowels has been omitted since American varieties do not show the close correlation of length with free vowels found in British NRP. Other important differences are listed below.

This type of patterning is particularly common in the New York conurbation and other eastern areas, but is also found to a degree elsewhere especially in high-frequency items such as dog, wrong, cost, off, etc.

/ in GA compared with /aIl/ in NRP, e.g. fertile /'fзr

/ in GA compared with /aIl/ in NRP, e.g. fertile /'fзr

/, missile /'mIs

/, missile /'mIs /. For certain words, alternative pronunciations with /aIl/ also exist (lexical variation).

/. For certain words, alternative pronunciations with /aIl/ also exist (lexical variation).

112

Say this sentence: Hairy Harry married merry Mary. Unless you’re American, you’ll probably have three vowels (in NRP they come in this sequence /εː æ æ e εː/). See if you can find some Americans willing to say the same sentence. Note how many vowels they have in their various idiolects.

There are some significant differences between British and American in (1) the allocation of stress, (2) the pronunciation of syllables such as -ary, -ery and -ory.

(1) Words borrowed from French are generally stressed on the first syllable in British English but they often have final-syllable stress in American.

GA |

NRP |

|

ballet |

/bæ'leI/ |

/'bæleI/ |

Bernard (first name) |

/br'nard/ |

/'bзːnəd/ |

Blasé |

/bla'zeI/ |

/'blaːzeI/ |

brochure |

/broƱ'∫Ʊr/ |

/'brəƱ∫ə/ |

Buffet |

/be'feI/ |

/'bƱfeI/ |

Baton |

/be'tan/ |

/'bæt |

Cliché |

/kli'∫eI/ |

/'kliː∫eI/ |

garage |

/gə'raƷ/ |

/'gæraːƷ/ |

perfume |

/p |

/'pзːfjuːm/ |

Tribune (newspaper) |

/trI'bjun/ |

/'trIbjuːn/ |

(2) Longer words ending in -ary, -ery and -ory take a secondary stress on those endings, and the vowel is neither reduced to /ə/ nor elided.

GA |

NRP |

|

military |

/'mIlə, teri/ |

/'mIlItəri/ or /'mIlItri/ |

cemetery |

/'semə, teri/ |

/'semətəri/ or /'semətri/ |

mandatory |

/'mændə, tɔri/ |

/'mændətəri/ or /'mændətri/ |

The following is a short list of individual words showing lexical variation not covered above. The pronunciations cited are those which appear to be found most commonly either side of the Atlantic. Note that in some cases a minority of American speakers may use forms which are more typical of British speakers and vice versa. Words of this type are indicated by arrows (→ and ← respectively).

Stress shift |

GA |

NRP |

address (n.) |

/'ædres/ → |

/ə'dres/ |

Chimpanzee |

/t∫Im'pænzi/ → |

/t∫Impæn'ziː/ |

Cigarette |

/'sIgəret/ → |

← /sIgə'ret/ |

detail |

/dI'teIl/ → |

/'diːteIl/ |

inquiry |

/'Iŋkwəri/ → |

/Iŋ'kwaIəri/ |

laboratory |

/'læbrətɔri/ |

← /lə'bDrətri/ |

moustache |

/'mλstæ∫/ |

/mə'staː∫/ |

Consonant variance

erase |

/I'reIs/ |

/I'reIz/ |

figure |

/'fIgjər/ |

/'fIgə/ |

herb |

/зrb/ |

/hзːb/ |

Parisian |

/pə'rIƷ |

/pə'rIziən/ |

puma |

/'pumə/ |

/'pjuːmə/ |

schedule |

/'skeʤul/ |

← /'∫eʤuːl/ |

suggest |

/səg'ʤest/ |

/se'ʤest/ |

Vowel variance

anti- |

/'æntaI/ → |

/'ænti/ |

ate |

/eIt/ |

← /et/ |

borough |

/'bзroƱ/ |

/'bλrə/ |

thorough |

/'θзroƱ/ |

/'θλrə/ |

clerk |

/'klзrk/ |

/klaːk/ |

depot |

/'dipoƱ/ |

/'depəƱ/ |

dynasty |

/'daInəsti / |

/'dInəsti/ |

docile |

/'das |

/'dəƱsaIl/ |

either |

/'iðər/ → |

← /'aIðə/ |

epoch |

/'epək/ |

/'iːpDk/ |

multi- |

/'mλltaI/ → |

/'mλlti/ |

neither |

/'niðər/ → |

← /'naIðə/ |

leisure |

/'liƷər/ |

/'leƷə/ |

lever |

/'levər/ → |

/'liːvə/ |

process (n.) |

/'prases/ |

/'prəƱses/ |

progress (n.) |

/'pragrəs/ |

/'prəƱgres/ |

record (n.) |

/'rekərd/ |

/'rekɔːd/ |

semi- |

/'semaI/ → |

/'semi/ |

shone |

/'∫oƱn/ |

/'∫Dn/ |

simultaneous |

/saIməl'teIniəs/ |

/sIməl'teIniəs/ |

tomato |

/tə'meI |

/tə'maːtəƱ/ |

vase |

/veIz, veIs/ → |

/vaːz/ |

vitamin |

/'vaI |

← /'vItəmIn/ |

what |

/wλt/ or /wat/ |

/wDt/ |

z (in alphabet) |

/zi/ |

/zed/ |

The pronunciation of similarly spelt names frequently varies between Britain and the USA, with a tendency for American versions to reflect spelling more closely. Some of the more familiar examples are the following:

GA |

NRP |

|

Berkeley |

/'bзrkli/ |

/'baːkli/ |

Birmingham |

/'bзrmIŋhæm/ |

/'bзːmIŋəm/ |

Burberry |

/'bзrberi/ |

/'bзːbri/ |

Derby |

/'dзrbi/ |

/'daːbi/ |

Warwick |

/'wɔrwIk/ |

/'wDrIk/ |

One of the most noticeable differences between GA and NRP setting is that American vowels are influenced by r-colouring, affecting adjacent consonants as well as vowels. For example, in partner, not only the vowels are affected but also the /t/ and the /n/. The body of the tongue is bunched up to a pre-velar position and the root of the tongue is drawn back in the pharynx. As compared with NRP, American English also appears more coloured by semi-continuous nasalisation running throughout speech. Many Americans, particularly of educated varieties, have noticeable creaky voice (see Section A4).

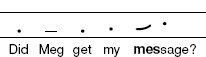

Much of what has been said about British intonation applies to GA intonation with this important difference: American intonation tends to have fewer of the rapid pitch changes characteristic of NRP, and rises and falls are more spread out over the whole tune. A very typical pattern, for instance, is this sort of rising tune for questions:

Perhaps because of these differences, American English is sometimes claimed to strike a British ear as ‘monotonous’. On the other hand, British English intonation is said to sound ‘exaggerated’ or ‘affected’ to Americans.

A second difference concerns rhythm. American English, because of a tendency to lengthen stressed checked vowels (e.g. TRAP) and an apparently slower rate of delivery, is stereotyped by the British as ‘drawled’. British English, because of the general tendency to eliminate weakly stressed vowels, together with an apparently more rapid rate of delivery, seems to strike many Americans as ‘clipped’.

Track 42

Track 42well – being a – semi-geek – in high school – I – was also in the marching band – and – basically – we had to – perform at football games – at the 4th of July Parade of course – and we had to wear these horrible uniforms – that were – in our school colours of course – red white and blue – made of 120 per cent polyester – and – we had to march in formation out on the football field – before the games and during half time – and one time we were marching – doing our little – kind of – sequence of movements on – the field – right before a game and the football players were – warming up – and I played the flute – and – at one point some guy from the opposing team – kicked the ball – out of control – and – the ball came flying towards me and hit me in – the mouth – which – hit my flute as well – luckily I didn’t have any broken teeth but I had a broken flute – and – a bloody lip – anyway – there was mass panic – the whole formation kind of fell apart – and – all these – you know – panicking women were running out onto the field to see what was wrong – and I was holding my – hand to my mouth – and – some women from the – I don’t know – what do you call it – the – what is it called – it’s kind of sports – this group of people who raise money for sports and kind of you know distribute the money and stuff for school activities – came over and started yelling at me to not get blood on my white gloves – that those white gloves cost ten dollars a pair or something – here I am – blood streaming from my mouth – my thousand-dollar flute in pieces – on the ground – and lucky to be alive – and she’s screaming at me about getting blood on my – gloves – anyway I quit marching band after that

geek = socially inept person

Our informant, Kathy, is a translator from the American Midwest. General American displays a degree of variation, so many, but not all, of the features described above can be identified in this small sample of Kathy’s speech. Her pronunciation is rhotic ( marching, warming, started) with noticeable r-colouring. She has consistent t-voicing (

marching, warming, started) with noticeable r-colouring. She has consistent t-voicing ( little, started, getting). There is no h-dropping (

little, started, getting). There is no h-dropping ( high, holding). In words like

high, holding). In words like  during, Kathy has yod-dropping. She uses TRAP in BATH words (

during, Kathy has yod-dropping. She uses TRAP in BATH words ( half). Her THOUGHT vowel is open, rather like NRP PALM (

half). Her THOUGHT vowel is open, rather like NRP PALM ( also, ball, called). Kathy doesn’t exhibit all the American features we have mentioned; for instance, initial /l/ isn’t noticeably dark, and her TRAP vowel is more open than average GA. Kathy (not being an easterner) doesn’t split NRP LOT words up into THOUGHT and PALM sets (see above) (

also, ball, called). Kathy doesn’t exhibit all the American features we have mentioned; for instance, initial /l/ isn’t noticeably dark, and her TRAP vowel is more open than average GA. Kathy (not being an easterner) doesn’t split NRP LOT words up into THOUGHT and PALM sets (see above) ( the vowels in dollar and wrong are the same), nor does she have any evidence of a FORCE–NORTH split. Like most younger GA speakers, she doesn’t contrast words spelt with w and wh (

the vowels in dollar and wrong are the same), nor does she have any evidence of a FORCE–NORTH split. Like most younger GA speakers, she doesn’t contrast words spelt with w and wh ( white, what, which are all said as /w/).

white, what, which are all said as /w/).

1 A more detailed comparison of American and British pronunciation can be found online at http://www.yek.me.uk/gavgb.html.