If you’ve picked up this book and are reading it, we can assume one or two things about you. First, you’re a human being – not a dolphin, not a parrot, not a chimpanzee. No matter how intelligent such creatures may appear to be at communicating in their different ways, they simply do not have the innate capacity for language that makes humans unique in the animal world.

Then, we can assume that you speak English. You are either a native speaker, which means that you speak English as your mother tongue; or you’re a non-native speaker using English as your second language; or a learner of English as a foreign language. Whichever applies to you, we can also assume, since you are reading this, that you are literate and are aware of the conventions of the written language – like spelling and punctuation. So far, so good. Now, what can a book on English phonetics and phonology do for you?

In fact, the study of both phonetics (the science of speech sound) and phonology (how sounds pattern and function in a given language) are going to help you to learn more about language in general and English in particular. If you’re an English native speaker, you’ll be likely to discover much about your mother tongue of which you were previously unaware. If you’re a non-native learner, it will also assist in improving your pronunciation and listening abilities. In either case, you will end up better able to teach English pronunciation to others and possibly find it easier to learn how to speak other languages better yourself. You’ll also discover some things about the pronunciation of English in the past, and about the great diversity of accents and dialects that go to make up the English that’s spoken at present. Let’s take this last aspect as a starting point as we survey briefly some of the many types of English pronunciation that we can hear around us in the modern world.

You may well already have some idea of what the terms ‘accent’ and ‘dialect’ mean, but we shall now try to define these concepts more precisely. All languages typically exist in a number of different forms. For example, there may be several ways in which the language can be pronounced; these are termed accents. To cover variation in grammar and vocabulary we use the term dialect. If you want to take in all these aspects of language variation – pronunciation together with grammar and vocabulary – then you can simply use the term variety.

We can make two further distinctions in language variation, namely between regional variation, which involves differences between one place and another; and social variation, which reflects differences between one social group and another (this can cover such matters as gender, ethnicity, religion, age and, very significantly, social class). Regional variation is accepted by everyone without question. It is common knowledge that people from London do not speak English in the same way as those from Bristol, Edinburgh or Cardiff; nor, on a global scale, in the same way as the citizens of New York, Sydney, Johannesburg or Auckland. What is more controversial is the question of social variation in language, especially where the link with social class is concerned. Some people may take offence when it is pointed out that accent and dialect are closely connected with class differences, but it would be very difficult to deny this fact.

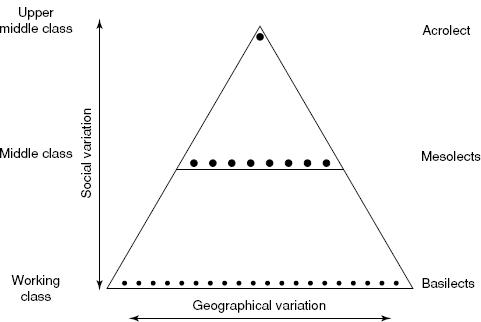

In considering variation we can take account of a range of possibilities. The broadest local accents are termed basilects (adjective: basilectal). These are associated with working-class occupations and persons less privileged in terms of education and other social factors. The most prestigious forms of speech are termed acrolects (adjective: acrolectal). These, by contrast, are generally found in persons with more advantages in terms of wealth, education and other social factors. In addition, we find a range of mesolects (adjective: mesolectal) – a term used to cover varieties intermediate between the two extremes, the whole forming an accent continuum. This situation has often been represented in the form of a triangle, sometimes referred to as the sociolinguistic pyramid (Figure A1.1). In England, for example, there is great variation regionally amongst the basilectal varieties. On the other hand, the prestigious acrolectal accent exhibits very few differences from one area to another. Mesolects once again fall in between, with more variation than in the acrolect but less than in the basilects. Note that the concept of the sociolinguistic pyramid (or ‘triangle’) is discussed in more detail by Peter Trudgill in Section D (pp. 286–93).

In the British Isles it is fair to say that one variety of English pronunciation has traditionally been connected with the more privileged section of the population. As a result, it became what is termed a prestige accent, namely, a variety regarded highly even by those who do not speak it, and associated with status, education and wealth. This type of English is variously referred to as ‘Oxford English’, ‘BBC English’ and even ‘the Queen’s English’, but none of these names can be considered at all accurate. For a long time, phoneticians have called it RP – short for Received Pronunciation; in the Victorian era, one meaning of ‘received’ was ‘socially acceptable’. Recently the term ‘Received Pronunciation’ (in the full form rather than the abbreviation favoured by phoneticians) seems to have caught on with the media, and has begun to have wider currency with the general public.

Figure A1.1The sociolinguistic pyramid

Traditional RP could be regarded as the classic example of a prestige accent, since although it was spoken only by a small percentage of the population it had high status everywhere in Britain and, to an extent, the world. RP was not a regional but a social accent; it was to be heard all over England (though only from a minority of speakers). Although to some extent associated with the London area, this probably only reflected the greater wealth of the south-east of England as compared with the rest of the country. RP continues to be much used in the theatre and at one time was virtually the only speech employed by national BBC radio and television announcers – hence the term ‘BBC English’. Nowadays, the BBC has a declared policy of employing a number of announcers with (modified) regional accents on its national TV and radio networks. On the BBC World Service and BBC World TV there are in addition announcers and presenters who use other global varieties. Traditional RP also happens to be the kind of pronunciation still heard from older members of the British Royal Family; hence the term ‘the Queen’s English’.

Within RP itself, it was possible to distinguish a number of different types (see Wells 1982: 279–95 for a detailed discussion). The original narrow definition included mainly persons who had been educated at one of what in Britain are called ‘public schools’ (actually very expensive boarding schools) like Eton, Harrow and Winchester. It was always true, however, that – for whatever reason – many English people from less exclusive social backgrounds either lost, or considerably modified, their distinctive regional speech and ended up speaking RP or something very similar to it. In this book, because of the dated – and to some people objectionable – social connotations, we shall not normally use the label RP (except consciously to refer to the upper-class speech of the twentieth century). Rather than dealing with what is now regarded by many of the younger generation as a quaint minority accent, we shall instead endeavour to describe a more encompassing neutral type of modern British English but one which nevertheless lacks obvious local accent features. To refer to this variety we shall employ the term non-regional pronunciation (abbreviated to NRP). We shall thus be able to allow for the present-day range of variation to be heard from educated middle and younger generation speakers in England who have a pronunciation which cannot be pinned down to a specific area. Note, however, that phoneticians these days commonly use the term ‘Standard Southern British English’, or SSBE for short.

Track 1

Track 1Jeremy: yes what put me off Eton was the importance attached to games because I wasn’t sporty – I was very bad at games – I was of a rather sort of cowardly disposition – and the idea to have to run around in the mud and get kicked in the face – by a lot of larger boys three times a week – I found terribly terribly depressing – fortunately this only really happened one time a year – at the most two – because in the summer one could go rowing – and then one was just alone with one’s enormous blisters – in the stream –

Interviewer: which games did you play though – or did you have to play –

Jeremy: well you had to play – I mean I liked – I was – the only thing I was any good at was fencing and I liked rather solitary things like fencing or squash or things like that – but you had to play – Eton had its own ghastly combination of rugger and soccer which was called the ‘field game’ – and that was for the so-called Oppidans [fee-paying pupils who form the overwhelming majority at Eton] like myself – and then there was the Wall Game – which was even worse – and that was for the college – in other words the non-paying students known as ‘tugs’ –

Interviewer: known as –

Jeremy: tugs –

Interviewer: ah right –

Jeremy: they were called tugs –

Interviewer: there was a lot of slang I suppose

Jeremy: there was a lot of slang – I wonder how much it’s still understood – and I don’t know if it still exists at Eton – whether it’s changed

Jeremy, a university professor, was born in the early 1940s. His speech is a very conservative variety, by which we mean that he retains many old-fashioned forms in his pronunciation. Jeremy, in fact, preserves many of the features of traditional Received Pronunciation (as described in numerous books on phonetics written in the twentieth century) which have since been abandoned by most younger speakers.

Track 2

Track 2Daniel: last time I went to France I got bitten – thirty-seven times by mosquitoes – it was really cool – I had them all up my leg – and I got one on the sole of my foot – that was the worst place ever – it’s really actually quite interesting – it’s really big – and we didn’t have like any – any mosquito bite stuff – so I just itched all week

Interviewer: what are you going to do this summer – except for going to France

Daniel: go to France – and then come back here for about – ten days – I’m supposed to get a job to pay my Dad back all the money that I owe him – except no one wants to give me a job – so – I’m going to have to be a prostitute or something – I don’t know – well – I’m here for ten days after I come back from France anyway – and then we go to Orlando on the 1st of August – for two weeks – come back and then I get my results – and if they’re good then – I’m happy – and if they’re not good – then – I spend – the next six weeks working – to do resits – and then end of September – go to university

You’ll notice straightaway that this speaker, Daniel, whose non-regionally defined speech is not atypical of the younger generation of educated British speakers, sounds different from Jeremy in many ways. Daniel grew up in the 1980s (the recording dates from 1996) indicating that well before the end of the twentieth century non-regional pronunciation (NRP) was effectively largely replacing traditional RP.

Of late, there’s been talk of a ‘new’ variety of British accent which has been dubbed Estuary English – a term originally coined by David Rosewarne (1984) and later enthusiastically embraced by the media. The estuary in question is that of the Thames, and the name has been given to the speech of those whose accents are a compromise between traditional RP and popular London speech (or Cockney, see Section C2). Listen to this speaker, Matthew, a university lecturer, who was born and grew up in London, and whose speech is what many would consider typical of Estuary English. Matthew’s accent is clearly influenced by his London upbringing, but has none of the low-status basilectal features of Cockney as described on pp. 169–70.

Track 3

Track 3Matthew: but generally speaking – I thought Sheffield was a lovely place – I enjoyed my time there immensely – some of the things that people said to you – took a little bit of getting used to – I did I think look askance the first time – I got on a bus – and I was called ‘love’ by the bus driver – but I wasn’t really used to this kind of thing at the time – I do remember one thing – it was delightfully quiet in Sheffield because – I grew up – in west London near the flight path of Heathrow – the first night I slept in Sheffield – I couldn’t sleep – and – this was despite some kind of – hideous sherry party which had been thrown to – loosen up the students in some kind of way – and eventually I worked out why I couldn’t sleep – and that was because it was so bloody quiet – I was used to the dim roar of Heathrow – and the traffic of the M4 and the A4 – vague hiss in the background – and to be confronted with a room to sleep in – where there was no noise whatsoever – was quite frightening really – and I think that was one of the reasons – that I developed the habit of wanting to go to sleep with music on – to protect me from this terrifying silence – now I must stress that Sheffield is not known for its silence generally – but the university part of the city – is in a very green area – well away from all of Sheffield’s industrial past as it were – and was actually a very quiet place – unless there was somebody running down your student corridor shrieking

Claims have been made that Estuary English will in the future become the new prestige British accent – but perhaps it’s too early to make predictions. What does seem certain, however, is that change is in progress, and that one can no longer delimit a prestige accent of British English as easily as one could in the early twentieth century. The speech of young educated speakers in the south of England indeed appears to show a considerable degree of London influence (Fabricius 2000) and we shall take account of these changes in our description of NRP. For an opposing viewpoint, you can find a discussion of the concept of Estuary English, regarding it as a ‘myth’, in the piece by Peter Trudgill in Section D10 (pp. 290–2). So perhaps it’s indeed too soon to tell. For further detail see Section C5, pp. 212–14.

A British model of English is what is most commonly taught to students learning English as a second language in Europe, Africa, India and much of Asia. In this book, NRP is the accent we assume non-native speakers will choose. Our main reason for selecting NRP is that English of this kind is easily understood not only all over Britain but also elsewhere in the world.

In Scotland, Ireland and Wales, notwithstanding the fact that there never were very many speakers of RP in those countries, the accent was formerly held in high regard (certainly this is less so nowadays). This was also true of more distant English-speaking countries such as Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Today scarcely any Australians, New Zealanders or South Africans consciously imitate traditional RP as was once the case, even though the speech of radio and television announcers in these countries clearly shows close relationships with British English. In the USA, surprisingly, there was also many years ago a tradition of using a special artificial type of English, based on RP, for the stage – especially for Shakespeare and other classic drama. Even today, the ‘British accent’ (by which Americans essentially mean traditional RP) retains a degree of prestige in the United States; this is especially so in the acting profession – although increasingly in the modern cinema it seems to be the villains rather than the heroes who speak in this manner! (Think of Anthony Hopkins and his portrayal of Hannibal Lecter.)

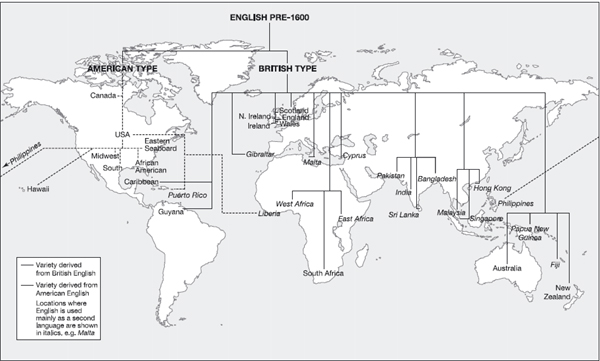

But in the twenty-first century any kind of British English is in reality a minority form. Most English is spoken outside the British Isles – notably in the USA, where it is the first language of more than 220 million people. It is also used in several other countries as a first language, e.g. Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the countries of the Caribbean. English is used widely as a second language for official purposes, again by millions of speakers, in Southern Asia, e.g. India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and in many countries across Africa. In addition, there are large second-language English-speaking populations in, for example, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Singapore. In total, there are probably as many as 330 million native speakers of English, and it is thought that in addition an even greater number speak English as a second language – numbers are difficult to estimate (Crystal 2003a: 59–71). Figure A1.2 (p. 8) provides a map showing the two family trees of British and American varieties of English. Locations populated largely by second-language English users are indicated in italics. See Crystal (2003a: 62–5) for a table giving estimates of first- and second-language English speakers in over 70 countries.

Let’s now look a little more closely at two regions of the world where English is used as a first language – North America (USA and Canada) and Australasia (Australia and New Zealand). In the United States, over the course of the last century, an accent of English developed which today goes under the name of General American (often abbreviated to GA). This variety is an amalgam of the educated speech of the northern USA, having otherwise no recognisably local features. It is said to be in origin the educated English of the Midwest of America; it certainly lacks the characteristic accent forms of East Coast cities such as New York and Boston. Canadian English bears a strong family resemblance to GA – although it has one or two features which set it firmly apart. On the other hand, the accents of the southern states of America are clearly quite different from GA in very many respects.

GA is to be heard very widely from announcers and presenters on television and radio networks all over the USA, and for this reason it is popularly known by another name, ‘Network American’. General American is also used as a model by millions of students learning English as a second language – notably in Latin America and Japan, but nowadays increasingly elsewhere. We shall return to this variety in Section C1.

Other varieties of English which are now of global significance are those spoken in Australia and New Zealand. Once again there is an obvious relationship between these two varieties, although they also have clear differences from each other. New Zealand English has distinct ‘South Island’ types of pronunciation – but there is surprisingly little regional variation across the huge continent of Australia. On the other hand, there is considerable social variation between what are traditionally termed ‘Broad Australian’, ‘General Australian’ and ‘Cultivated Australian English’. The first is the kind which most vigorously exhibits distinctive Australian features and is the everyday speech of perhaps a third of the population. The last is the term used for the most prestigious variety (in all respects much closer to British NRP); this minority accent is not only to be heard from television and radio presenters but is also, in Australia itself, taught as a model to foreign learners. General Australian, used by the majority of Australians, falls between these two extremes.

Finally, we have to remember that while there are so many different world varieties of English, they are essentially (at least in their standard forms) very similar. In fact, although the differences are interesting, it’s the degree of similarity characterising these widely dispersed varieties of English which is really far more striking. English as used by educated speakers is readily understood all over the world. In fact, it is unquestionably the most widespread form of international communication that has ever existed.