One of the most useful day-to-day applications of phonetics courses is learning the pronunciation of a foreign language. In this section we deal with (1) teaching English to non-native learners; (2) the problems native speakers of English have in learning a foreign language. We shall use the abbreviation L1 (i.e. first language) to refer to the learner’s mother tongue (also termed ‘source language’) and L2 (i.e. second language) to refer to the language which is being learned (also termed the ‘target language’).

In learning a language it is necessary to have realistic goals. Unless you begin in your infancy, it is very unlikely that you will ever achieve a perfect command of a language. Nowhere is this more true than of pronunciation. Even if you start in your teens, and go to live in the country concerned, it is likely that you will have some traces of a foreign accent all your adult life. If perfect pronunciation is your target then you must accept that you will inevitably fall short of it. A realistic aim is therefore to speak in a way which is clearly intelligible to your listeners and which does not distract, irritate or confuse them.

So a major consideration when dealing with pronunciation is to discover which errors are the most significant. Not all deviations from native-speaker pronunciation are of equal importance (see Jenkins 2000). Some pass unnoticed whereas others may be enough to cause total lack of comprehension on the part of the listener. In trying to establish a hierarchy of error we must take into account the reactions of native speakers. In general terms we can rank errors in the following way.

Obviously, the first category of error listed above is crucial and requires the most attention from teacher and student. The second group can also be of significance and are often those features which draw attention to the foreignness of an accent. The third category is of far less importance. In fact, it is unusual for an isolated error even of a category 1 type above to lead to a breakdown of intelligibility. But an important factor–which is often underestimated or ignored in contrastive analysis–is that pronunciation errors do not typically occur in isolation. Especially with beginners or less proficient speakers, the L2 speech of the learner is likely to be peppered with numerous errors in every sentence. Consequently a build-up effect results and causes problems of intelligibility. For example, there may be confusion of fortis/lenis consonants, together with loss of significant vowel contrasts like KIT–FLEECE and TRAP–DRESS. On top of that, there may be problems with stress and rhythm. If one then adds the likelihood of other linguistic errors (for instance, grammatical, or choice of vocabulary) then it’s not surprising that the English of non-natives can sometimes be difficult, or even impossible, to understand.

Below, examples will be given of each of the three types of error with an indication of speakers’ L1. Note that ‘widespread’ implies an error that is likely to be made by people from a large number of language backgrounds.

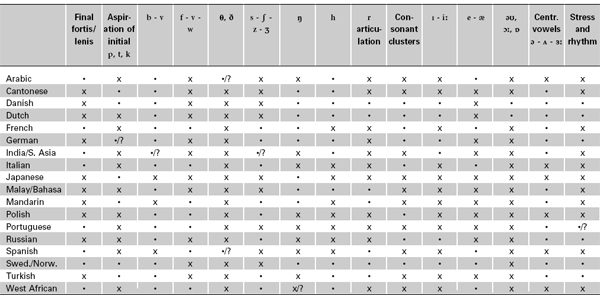

For an overview, see Table C6.1, p. 217.

Errors made by language learners frequently reflect the sound systems of their L1. If we compare the L1 sound system with that of the L2, we can often predict the nature of errors which they will make. Let’s take as an example the case of a speaker of European Spanish (or Castellano, see below) learning English.

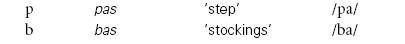

Spanish lacks a phoneme contrast similar to English /b–v/, the Spanish /b/ having a range of allophones similar to the two English consonants. There will be regular deletion of /h/ or replacement by the velar fricative [x]. On the other hand, unlike many languages, European Spanish has a voiceless dental fricative /θ/, and [ð] exists as an allophone of /d/, even though in the latter case English words containing /d/ and /ð/ will be regularly confused.

The syllable structure of Spanish is less complex than that of English. For example, there are no onset clusters with initial /s/, and the possibilities in coda position are far fewer (only final /n l r s d θ/ occur with any frequency). Final consonants and consonant clusters in general are a major problem area for Spanish speakers. This means that spam will be produced by learners as */espan/ (better not let a Spanish speaker loose on old Monty Python songs!).

European Spanish has a five-vowel system with a number of additional diphthongs. There is no equivalent to the checked/free vowel distribution in English, nor are there any central vowels similar to /ə зː Λ /. From this one would predict that a Spanish learner would have considerable problems with the English vowel system, and that the checked/free vowel contrasts and the central vowels would be especially problematical. For example, vowel contrasts such as /I–iː, Ʊ–uː, æ–aː/ might pose difficulties.

Spanish has syllable-timed rhythm–very different from the stress-timed rhythm of English (see Section B6). A characteristic of Spanish English is the absence of vowel reduction in unstressed syllables. The range of intonation is less extended than in the English of native speakers. Spanish learners will not possess the elaborate systems of weak and contracted forms which characterise native-speaker English.

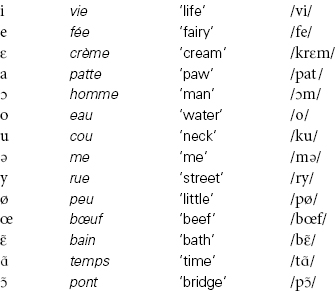

Table C6.1Survey of English pronunciation errors in a selection of languages and language groupings

x Highly significant problem areas

• Although some difficulties may arise, these errors are (in general) less significant problem areas

? Variation between one language/language variety and another

This table is intended only as a very simplified overview. More detailed analyses for a range of European and Asian languages can be found in Swan and Smith (2001) and Walker (2010); Deterding and Poedjosoedarmo (1998) provides much useful information on the pronunciation of the languages of South East Asia.

Let’s now examine the situation of learners who speak Japanese–a language with far more discrepancies from English.1 Again, many of the problems can be traced back to the differences between the phonemic inventories of the two languages. A well-known problem area is the English contrast /l–r/ as in rate–late or fright–flight. This results from the Japanese /r/ phoneme having a range of allophones which to English ears sound similar to either English /l/ or /r/. As in Spanish, Japanese [b] and [v] are allophones of a single phoneme /b/; consequently learners confuse English words like banish–vanish and TB–TV. Japanese /h/ has an allophonic range comprising [φ h ç]. In some contexts, Japanese /h/ transfers successfully into English, but there is also negative transfer. Before the close back vowels goose and foot, learners replace English /h/ by what English speakers perceive as a type of /f/ sound (actually, it’s a bilabial fricative [φ]), so that a Japanese attempt at who’d is heard as food. Preceding close front vowels FLEECE and KIT, the /h/ replacement is palatal fricative [ç]; to an English ear the Japanese pronunciation of he sounds a little like she. Phonetic training is helpful in all of these cases to assist the learners in knowing which allophone is appropriate for which phonetic context.

Like many languages, Japanese lacks dental fricatives. Learners replace English /θ/ by /s/, and /ð/ by /z/, making theme sound like seem, and breathe like breeze. In Japanese, alveolar consonants /s z t d n/ are palatalised (see pp. 58–60) before /i/. This feature is transferred to English so that before close front FLEECE and KIT, /s/ sounds like English palato-alveolar /∫/, blurring the contrast /s–∫/ and making seat sound like sheet; the contrast /z–Ʒ/ is also affected.

Like Spanish, Japanese has an economical basic vowel system of just five vowels. English checked/free vowel contrasts such as FLEECE–KIT, GOOSE–FOOT (e.g. beat–bit and pull–pool) indeed prove problematical. Nevertheless, since Japanese has many vowel sequences which have some similarities to English long vowels and diphthongs (see pp. 238–9), it is possible with phonetic training and practice for learners to approximate to a wider range of English vowel sounds. Japanese speakers will still find it difficult to master the differences in vowel length resulting from pre-fortis clipping (see p. 58), but, once again, raising phonetic awareness can be of great help. As in Spanish, a crucial gap is the complete lack of any central vowels. Problems arise with English /ə/ (the bonUs vowel), both in weak forms (see pp. 21–5) and with vowel reduction in unstressed syllables. As a first step, learners should be made aware that any letter can represent /ə/. Japanese learners regularly replace the central NURSE vowel by PALM, so that stir sounds like star. English TRAP, STRUT and PALM may all be perceived by learners as Japanese /a/, and this will transfer to pronunciation so that hut and hat, and possibly heart, all sound alike.

Japanese has simpler syllable structure than English (see p. 239). Since in Japanese only one consonant–the velar/uvular nasal [N]–can occur as a coda, learners will have problems with English closed syllables. The lack of Japanese final nasal contrasts transfers to English so that syllable-final nasals /m n ŋ/, as in the words ram, ran and rang, all sound the same. A serious Japanese error is to add an epenthetic vowel to a word-final consonant, e.g. ‘petto’ pet, ‘dokku’ dog. Except before /j/, no consonant clusters exist in Japanese, and learners also often add epenthetic vowels to English with most unfortunate results, e.g. club as [kurabu] and dream as [dorːimu]. These superfluous vowels are perhaps the most significant errors for beginners, regularly leading to intelligibility breakdown.

Japanese intonation has a narrower pitch range than English and learners find it difficult to distinguish a nucleus. Nevertheless, on the whole, intonation is not a major problem. Far more significant are the complications of mora-based rhythm (see pp. 239–40), which mean that Japanese rhythm is much closer to syllable-timing than it is to the stress-timing of English. This, together with the lack of vowel reduction (see above), and absence of weak forms, explains why learners find it difficult to reduce the length of English unstressed syllables.

A useful simplified summary of Japanese learners’ errors in English is provided by Shimizu (2010).

The problems of learners from other language backgrounds also reflect transferred features of their L1s. For example, speakers of Polish and Italian–languages which have simple vowel systems with no central vowels–will have difficulties with the complexities of the richer English vowel system. In particular, the English central vowels, such as bonus, NURSE and STRUT, prove major problems. Even if you speak a language with a complex vowel system like French, errors may arise from gaps in the L1. In fact, French learners of English stumble over checked vs. free vowel contrasts (confusing the KIT–FLEECE vowels), and the diphthongs vs. steady-state vowels (confusing GOAT and THOUGHT).

An overall lack of word-final lenis consonants affects English learners from many language backgrounds including German and Polish. This implies that pairs such as bet–bed, safe–save will be confused. Apart from Spanish, none of the languages we have dealt with have dental fricatives similar to /θ ð/, so that learners from all the other language backgrounds we discuss here usually replace these sounds with /t d/ or /s z/, e.g. these things as /diːz 'tIŋz/ or /ziːz 'sIŋz/. We have already mentioned that English /h/ poses problems for Spanish and Japanese learners of English, and this also applies to learners with French, Italian or Polish as L1. The articulation of English postalveolar /r/ is frequently an obstacle (especially for beginners) for French and Germans, whose /r/ is uvular. Unlike Japanese and Spanish learners, speakers of Polish, German or French will have fewer problems with English consonant clusters, since their own languages contain many complex consonant sequences.

Although languages show considerable intonational variation, and exact mimicry of intonation patterns is extremely difficult for most learners, deficiencies in this area hardly ever cause any breakdown in intelligibility, so its importance should not be overestimated. Much more significant is rhythm, and the impact of English stresstiming (see pp. 135–8), where speakers from many language backgrounds, including French, Spanish, Italian, Polish and Japanese, will encounter difficulties. French speakers, whose language lacks word stress and has invariable nucleus location, have particular problems here. On the other hand, speakers of German, Dutch or Scandinavian languages, whose L1s also have stress timing similar to English, are at a considerable advantage.

It will be seen that the main areas of difficulty for learners can indeed be largely predicted from contrastive analysis. Interestingly, not all learners’ difficulties can be predicted in this way, while some expected problems may fail to materialise. It is, however, no exaggeration to say that a great many second-language pronunciation problems can indeed be traced back to the sound system of the learners’ L1.

Other errors may arise through difficulties derived from confusing spelling systems–particularly in the case of target languages like English (or French or Danish), which have archaic orthography incorporating many perplexing sound–spelling relationships. In other cases, we may be faced with teaching traditions which are inaccurate or out of date–this may be the reason for the German reluctance to distinguish trap and dress when two reasonably adequate vowels for the contrast exist in their L1 (namely /a/ as in acht ‘eight’ and /ε/ as in Bett ‘bed’).

For an overview of the chief learners’ pronunciation errors from a variety of languages, see Table C6.1, p. 217. For a general survey and discussion of the many factors involved in teaching the pronunciation of a language to non-native learners, see the extract from Avery and Ehrlich (1992), reprinted in Section D4 (pp. 258–61).

It is essential to decide on a model for your students–this will normally be either British NRP or General American, for the reasons outlined in Section A1. Your own speech does not have to conform to the model but you should be aware of where you deviate markedly from it.

You should also make yourself aware of the problems your students have by giving them brief diagnostic tests. If you’re based in a non-English-speaking country, and your students all have the same L1, you can assume that they will probably have a large number of pronunciation problems in common. If, as is generally the case when teaching in an English-speaking country, you’re faced with students from many different language backgrounds, you have to approach the problems of each nationality separately.

In all cases, your task will be helped if you gain some phonetic knowledge of the L1s of the students in your classes. There are a number of practical ways in which this can be done. If, for example, you are teaching a class of Italian students, you can:

use books and audio material designed to teach Italian;

use books and audio material designed to teach Italian;

read courses on English, aimed at Italians, where pronunciation problems are discussed;

read courses on English, aimed at Italians, where pronunciation problems are discussed;

talk about the pronunciation of Italian with the students themselves;

talk about the pronunciation of Italian with the students themselves;

try to learn at least a smattering of Italian (see p. 221 on learning a foreign language);

try to learn at least a smattering of Italian (see p. 221 on learning a foreign language);

go to websites for information (Wikipedia has useful descriptions of many languages).

go to websites for information (Wikipedia has useful descriptions of many languages).

How can phonetics help you if you’re an English native speaker learning a foreign language? If you have acquired the language in school, perhaps the first thing to recognise is that you may need to do a lot of repair work. Many language teachers feel they do not have sufficient time to give their students prolonged pronunciation training. Some, indeed, devote no time to it whatsoever. All too often, language labs, where they exist, are locked up gathering dust whilst the students who should be allowed to use them plod away on written exercises.

Nevertheless, it’s amazing how quickly great improvements can be achieved in your pronunciation by applying a few basic phonetic principles.

consonant and vowel systems;

consonant and vowel systems;

sound and spelling relationships;

sound and spelling relationships;

stress, rhythm and other features of connected speech.

stress, rhythm and other features of connected speech.

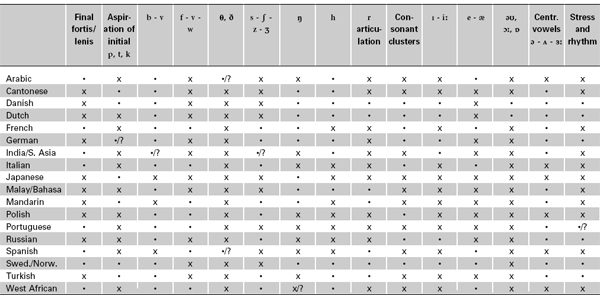

Here are four concise overviews which will help you use your phonetic expertise to gain a better understanding of the pronunciation of Spanish, French, German and Italian–all very popular languages for non-natives to learn. We go on to discuss two major languages, Japanese and Polish, which are less commonly studied outside their national borders, but which have many interesting phonetic/phonological features. Note that these summaries are all very brief and deliberately simplified.

Audio on Website

Audio on WebsiteThere may be as many as 350 million native speakers of Spanish worldwide. This implies that Spanish has overtaken English as the second most widely spoken language in the world (after Mandarin Chinese) in terms of native speakers, although not in terms of total language usage.

Over 40 million native speakers, plus 5 million fluent bilinguals, live in Spain itself. It is worth noting that Spain not only has a number of regional varieties but also has several other languages spoken within its borders, e.g. Catalan, Galician and the non-Indo-European language Basque. Castellano /kaste'jano/ is the term used in the Spanish-speaking world for the educated variety spoken in northern Spain, including the capital Madrid and the provinces of Castile. This is the model of Spanish usually chosen by European learners, but an alternative is a Latin American variety, such as Argentine Spanish. European and Latin American Spanish are at variance in many respects, but the most significant pronunciation difference is the existence in Castellano of a phoneme /θ/ used for orthographic z (e.g. zapata ‘shoe’) and for c preceding front vowels (cinco ‘five’). In all of Latin America, and also in Andalusia in the south of Spain, /s/ is employed in this context. As is always the case in language learning and teaching, it is best to be consistent–choose one model and stick to it. We shall assume in what follows that you are a British NRP speaker aiming at Castellano.

Some speakers have an additional phoneme /λ/ in words containing orthographic ll, as in llave /'λabe/. The voiced plosives /b d g/ have fricative allophones [β ð  ] when occurring between vowels, as indicated in the list above.

] when occurring between vowels, as indicated in the list above.

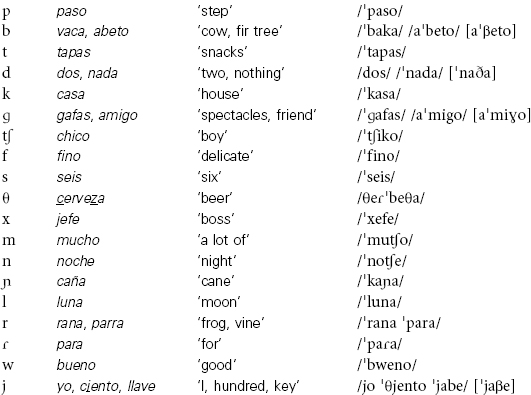

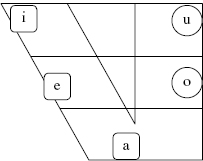

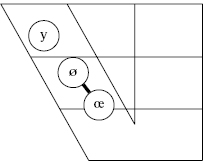

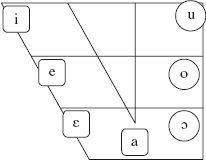

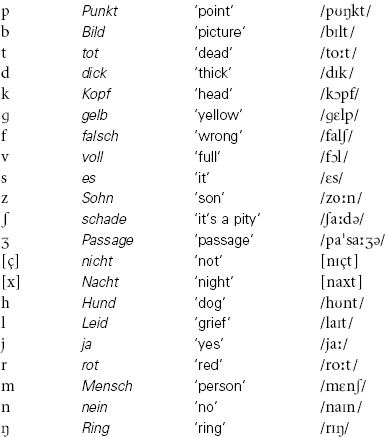

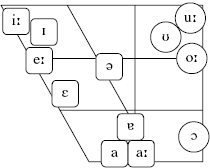

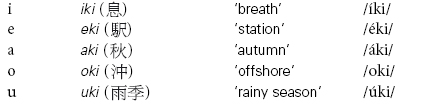

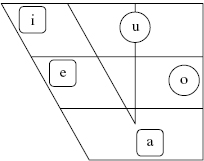

Figure C6.1Basic Spanish vowels

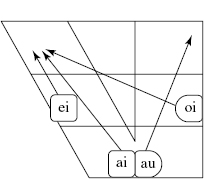

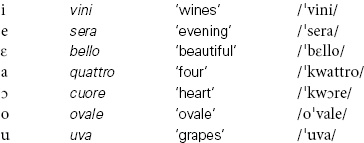

Figure C6.2Frequent Spanish diphthongs

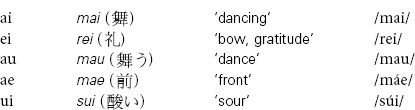

All vowels can combine to form diphthongs, but only /ei ai au oi/ commonly occur. Vowel sequences having initial /i/ and /u/ are regarded as semi-vowels /j/ and /w/. See below.

A new sound which must be mastered by the English learner of Spanish is the velar fricative /x/–spelt j or g (before i and e), as in jefe ‘boss’, general ‘general’. Double ll, as in paella, was traditionally a palatal lateral [λ] (a rough approximation is to pronounce it as in English /lj/), but is nowadays overwhelmingly said as [j] (far easier for an English learner to copy).

Unlike non-rhotic English, Spanish /r/ is pronounced in all contexts; deleting /r/ is a common British learner’s error. The Spanish sounds are also articulated very differently from English /r/, being typically a tongue-tip trill /r/ or tap / /. A major problem occurs in word-medial position where single r (alveolar tap) and double rr (alveolar trill) produce minimal pairs, contrasting, for example, para ‘for’ and parra ‘grapevine’.

/. A major problem occurs in word-medial position where single r (alveolar tap) and double rr (alveolar trill) produce minimal pairs, contrasting, for example, para ‘for’ and parra ‘grapevine’.

The tilde ˜ accent placed over ñ indicates a palatal nasal / / as in mañana ‘tomorrow’. Replacement by /nj/ similar to English onion is only an approximation, but it doesn’t seriously affect intelligibility.

/ as in mañana ‘tomorrow’. Replacement by /nj/ similar to English onion is only an approximation, but it doesn’t seriously affect intelligibility.

The voiced plosive consonants /b d g/ have weaker voiced fricative allophones [β ð  ]. The plosive allophones occur word-initially and following nasals; the fricatives are used elsewhere.

]. The plosive allophones occur word-initially and following nasals; the fricatives are used elsewhere.

It is recommended, if you’re imitating Castellano, that c (before front vowels) and z are pronounced as /θ/ rather than /s/. In Spain, using /s/ in this context is associated with particular regional varieties and may attract social comment.

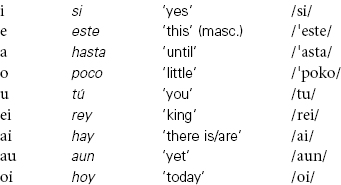

Standard Spanish has an attractively simple five-vowel /i e a o u/ system plus a number of diphthongs, the most significant of these being /ei ai oi au/. The two main problems are:

to avoid diphthongisation of /o/ and /e/ (which will cause confusion with diphthongs /ei/ and /ou/);

to avoid diphthongisation of /o/ and /e/ (which will cause confusion with diphthongs /ei/ and /ou/);

to avoid reducing unstressed vowels to [ə]. (Note that there is no central vowel of any kind in Spanish.)

to avoid reducing unstressed vowels to [ə]. (Note that there is no central vowel of any kind in Spanish.)

In general, Spanish orthography is highly reliable and efficient. Nevertheless, there are potential pitfalls. Note that h is invariably a ‘silent letter’ and either the letter b or v could be regarded as superfluous as they are exact equivalents, both representing /b/. The letter combination qu represents [k] queso ‘cheese’; c represents [θ] before front vowels i and e, e.g. cine ‘cinema’, cero ‘zero’ but [k] elsewhere: calle ‘street’.

Vowel spellings in Spanish are very straightforward with effectively no complications.

Word stress in Spanish operates on a basic rule system whereby stress falls regularly on the penultimate syllable if the word ends in a vowel, n or s, e.g. ven'tana, ‘window’, 'manos ‘hands’, 'cantan ‘they sing’. Words ending in a consonant (other than n or s) are stressed on the final syllable, e.g. ani'mal ‘animal’, co'ñac ‘brandy’, ha'blar ‘to speak’, etc. All of the fairly large number of words which are exceptions to these rules have stress indicated by an accent placed over the stressed syllable, e.g. volcán ‘volcano’, cámara ‘room’, compás ‘compass’, difícil ‘difficult’. Note that word stress is significant in Spanish and can change the meaning of words: término (noun) ‘end’, termíno ‘I finish’, terminó ‘he finished’.

There is no reduction of unstressed syllables to a fully central vowel. Rhythm is essentially syllable-timed, each syllable giving the impression of having roughly equal duration. English speakers accustomed to the stress-timing of their own language have to try to give every syllable in Spanish full value.

In Spanish, there is no clear separation of syllables across word boundaries. ‘All the words seem to run into each other’ is one of the commonest complaints of students attempting to acquire the language–and this feature is indeed one of the major listening comprehension problem areas for the non-native learner.

Mott (2011) contains much contrastive information on Spanish and English pronunciation.

Audio on Website

Audio on WebsiteEurope has perhaps as many as 70 million native speakers of French (over 60 million in France, well over 4 million in Belgium, and 2 million in Switzerland). In addition, there are approximately 7 million Canadian native speakers. There are also large numbers of second language speakers, most especially in vast areas of West and Central Africa, where French is the official language.

Although France has many regional accents, only one variety of the language is normally chosen as a model for foreign learners. This is the educated standard variety of Paris and the north, which has no commonly used special name, but has been termed français neutre (Lerond 1980).

1 /ɳ/ is a marginal phoneme (see Section B1) found only in loanwords ending in -ing.

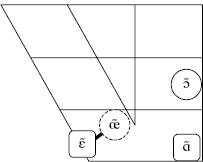

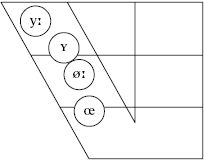

Figure C6.4French front rounded vowels. The line indicates a close phonological relationship

Figure C6.5French nasal vowels. The line indicates a close phonological relationship

The bands in the vowel diagram indicate vowels where there is a close relationship of some kind. The vowels /ε/ and /ɔ/ occur in closed syllables, whereas /e/ and /o/ are found mostly in open syllables. Some speakers, mainly of the older generation, have an additional nasal vowel / /, as in un, brun /

/, as in un, brun / br

br /. Others (especially older Parisians) make a distinction between two open vowels /a/ and /a/ as in patte ‘paw’ and pâte ‘paste’. Neither of these extra contrasts is nowadays heard in the French of younger speakers of the standard language.

/. Others (especially older Parisians) make a distinction between two open vowels /a/ and /a/ as in patte ‘paw’ and pâte ‘paste’. Neither of these extra contrasts is nowadays heard in the French of younger speakers of the standard language.

While there is much overall similarity in the consonant systems of French and English, there are also some notable differences. Unlike English /p t k /, French voiceless plosives are unaspirated and never glottalised. Getting rid of aspiration and glottalisation (see Section B2) is one of the most important problems the English-speaking learner has to face. Unlike NRP, French /r/ is typically sounded in all contexts; it is a totally different articulation from its English counterpart, being realised as a back tongue uvular approximant [ ]. English post-alveolar /r/ is completely unacceptable if transferred to French. If you want to sound even remotely authentic in French, uvular [

]. English post-alveolar /r/ is completely unacceptable if transferred to French. If you want to sound even remotely authentic in French, uvular [ ] is the one essential consonant to master.

] is the one essential consonant to master.

French /l/ is invariably clear – there is no dark l as in NRP and most types of English (modern English vocalised dark l may sound like a back vowel to French ears). Note that final m and n are not true consonants, but normally merely indicate that the preceding vowel is nasal (see below). The palatal nasal / / in cygne ‘swan’, in agneau ‘lamb’ can nowadays safely be replaced by /nj/.

/ in cygne ‘swan’, in agneau ‘lamb’ can nowadays safely be replaced by /nj/.

All French vowels can vary in duration, for instance being longer in open syllables, but this vowel length is phonemically insignificant. Vowels are all steady-state, not diphthongs, and it is important not to diphthongise vowels such as /o/ in beau ‘beautiful’ and /e/ in fée ‘fairy’. Two crucial features of the French sound system which you have to master are (1) front rounded vowels and (2) nasal vowels.

(1) Front rounded vowels are made with the front of the tongue raised but with rounded lips (see Section A6). They include /y/ as in tu ‘you’ (similar to a lip-rounded [i] vowel), and /ø/ in peu ‘little’ (similar to a lip-rounded [e]); a third vowel /œ/ (similar to a lip-rounded [ε]) occurs in closed syllables, e.g. neuf ‘nine’ /nœf/.

The vowel /y/, always spelt u, must be kept distinct from /u/, always spelt ou as in tout ‘all’. There are many pairs where the meaning is dependent on this contrast. Make sure that French /u/ is a true back vowel (lots of young NRP speakers produce a fronted vowel for English /uː/). Many English speakers hear the vowels in peu and neuf in terms of the vowel in nurse. However, the French vowels are strongly lip-rounded and this rounding must be imitated. Check by looking in a mirror.

(2) There are three nasal vowels in French, namely / /, as in vin ‘wine’ (similar to a nasalised English /æ/), /ã/, as in banc ‘bench’ (similar to an unrounded nasalised English /D/), and /

/, as in vin ‘wine’ (similar to a nasalised English /æ/), /ã/, as in banc ‘bench’ (similar to an unrounded nasalised English /D/), and / / as in bon ‘good’ (similar to a fully rounded nasalised English /ɔː/). Note that it is essential to distinguish the vowels /ã/ and /

/ as in bon ‘good’ (similar to a fully rounded nasalised English /ɔː/). Note that it is essential to distinguish the vowels /ã/ and / / (most English people don’t!). On the other hand, the old /

/ (most English people don’t!). On the other hand, the old / / – /aet/ contrast, still taught in most British schools, is superfluous. As mentioned above, the vowel /aet/ is extinct in most standard modern French, having effectively been replaced by /

/ – /aet/ contrast, still taught in most British schools, is superfluous. As mentioned above, the vowel /aet/ is extinct in most standard modern French, having effectively been replaced by / /, e.g. /br

/, e.g. /br / brun, ‘brown’, /l

/ brun, ‘brown’, /l di/ lundi ‘Monday’. Note that many younger speakers use an open central vowel in between the two.

di/ lundi ‘Monday’. Note that many younger speakers use an open central vowel in between the two.

Nasal vowels are indicated in the spelling by syllable-final n or m. These orthographic consonants are not themselves sounded, which means, for example, that conte ‘tale’ and compte ‘account, charge’ sound exactly the same: /k t/.

t/.

The French spelling system is archaic and full of confusing complexities, but it is essential to take note of spelling–sound relationships. ‘Silent consonants’ abound; to give just a few examples: heure ‘hour’, nez ‘nose’, tabac ‘tobacco’, banc ‘bench’, sirop ‘syrup’, sot ‘stupid’, respect ‘respect’, frais ‘cold’, tard ‘late’. A number of words show variation: août ‘August’ may be pronounced /ut/ or /u/; tous ‘all’ can be /tu/ or /tus/.

Silent consonants, especially in the commonest words, often return in connected speech as liaison forms. Compare:

vous /vu/ ‘you’vous avez /vuz ave/ ‘you have’

vingt /v / ‘twenty’vingt-et-un /v

/ ‘twenty’vingt-et-un /v t e

t e  / ‘twenty-one’

/ ‘twenty-one’

Orthographic e (without any accent) is silent when word-final (e.g. huile ‘oil’ /ɥil/), and often when word-medial; see below.

There are frequently numerous ways of indicating the same sound. For instance, the words tan ‘tan’, taon ‘horsefly’, tant ‘so much’, tend ‘stretch’, temps ‘time, weather’ are homophones, all pronounced identically as /tã/, despite the different spellings.

Note that two of the orthographic accents of French are in phonetic terms largely superfluous. The circumflex (^) no longer serves its original purpose of indicating vowel length, and in reality there is no longer any consistent difference between è (accent grave) and é (accent aigu or ‘acute’). However, the presence of an accent on e still has a very important function: é indicates that the vowel is fully sounded and not reduced to [ə] or elided, cf. ménage /mεnaƷ/ ‘household’ and menace /m(ə)nas/ ‘threat’.

Note that on other vowels a grave accent serves only to distinguish words which would otherwise be spelt identically (e.g. ou ‘or’ vs. où ‘where’), and has no phonetic function.

Audio on Website

Audio on WebsiteLike Spanish, French has no clear separation of syllables across word boundaries. Learners usually find the effect of ‘words running into each other’ to be the most difficult aspect of listening comprehension, while liaison processes (see above) add further complications.

Stress is not essential to the phonological structure of the word in French. This makes French very different from English (or indeed most European languages) where the correct placement of stress is crucial for the recognition of polysyllabic words. See also Section B6.

In French, stress is predictable, falling on the final syllable of any word or phrase if pronounced in isolation, or on the final syllable of each intonation group in connected speech. (English-speaking learners of French are usually totally unaware of this important basic principle.) For example:  Audio on website

Audio on website

é 'tat \ ‘state’

les Etats-U 'nis \ ‘the United States’

Je voudrais par 'tir \ pour les Etats-U 'nis \ de'main. \ ‘I’d like to go to the United States tomorrow.’

Furthermore, French is syllable-timed, which implies that one needs to pronounce all syllables with roughly equal force and length. An important extra complication – especially in terms of listening comprehension – is that syllables spelt with unaccented e (1) reduce to /ə/ and (2) are almost invariably elided, so producing sequences of two consonants, e.g. demi ‘half’ /dəmi/ → /dmi/, petit ‘small’ /peti/ → /pti/, boulevard /bulevar/ → /bulvar/.  Audio on website

Audio on website

Note, however, that spoken French avoids sequences of three consonants, and where these could potentially exist, orthographic e is sounded as /ə/, e.g. carte bancaire ‘bank card’ /kartə bãkεr/. If no e occurs in the spelling, an epenthetic /ə/ may be inserted, e.g. un film fantastique ‘a fantasy film’ / filmə fãtastik/.

filmə fãtastik/.

A useful brief summary is Fougeron and Smith (1999). More detail is to be found in Tranel (1987). A reliable French pronunciation dictionary is the Larousse Dictionnaire de la prononciation (Lerond 1980).

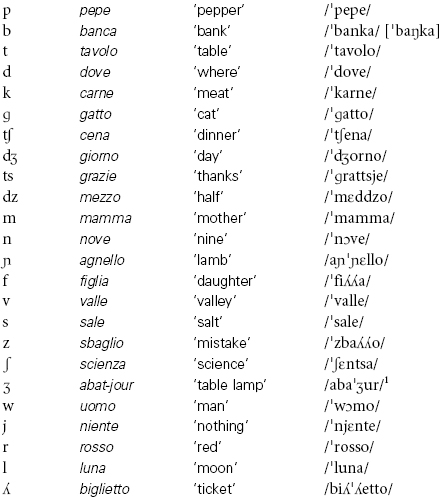

Italian is spoken throughout Italy and is one of Switzerland’s official languages.2 Although there are many local accents and dialects, what is coming to be regarded as the standard language – and a model for non-native learners – is based on a geographically central variety (including the city of Rome) but lacking marked regional features. This accent is increasingly heard on the media and is sometimes referred to as ‘RAI’ /rai/ pronunciation (after the Italian national broadcasting service Radiotelevisione Italiana).

1 /Ʒ/ is a marginal phoneme (see p. 77) found mainly in French loanwords.

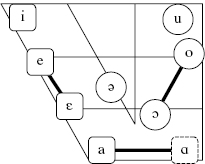

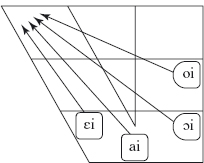

Figure C6.6Basic Italian vowels

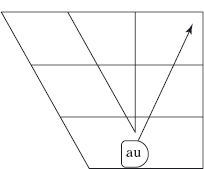

Vowels combine to produce a number of diphthongs, the most significant of these being /ai/ and /εi/: giocherai /ʤoke'rai/ ‘you will play’; giocherei /ʤoke'rεi/ ‘I would play’. Other diphthongs include /au/ as in cauto /'kauto/ ‘cautious’, /oi/ as in voi /voi/ ‘you’ (pl.), and /ɔi/ as in poi /pɔi/ ‘then’.

Figure C6.7Frequent Italian diphthongs

Most of the Italian consonants have counterparts in English, although often with considerable phonetic differences. See below for the significance of consonant doubling and spelling conventions.

All consonants, except /z Ʒ j w/, can be ‘doubled’ – an effect which in Italian is termed raddoppiamento. Doubling a consonant not only lengthens the consonant itself but also shortens the preceding vowel. These effects can at first be difficult for the beginner to hear and might therefore be thought unimportant – but nothing could be further from the truth! To Italians it is one of the most significant features of the language, and it can often change or blur the meaning in a pair of words, e.g. nono ‘ninth’ /'nɔno/ vs. nonno ‘grandfather’ /'nɔnno/. Other examples (with a different mid-vowel) are: sete ‘thirst’ /'sete/ vs. sette ‘seven’ /'sεtte/ and velo ‘veil’ /'velo/ vs. vello ‘fleece’ /'vεllo/. Note that raddoppiamento is not only indicated by a double letter but also by the spellings sc, z, gl and gn (see below).

Start imitating Italian doubling by taking account of a similar effect in English which normally occurs across word boundaries. If you say phrases like hard disk, rough figures, nice sauce, one nation, and full length, you’ll notice that you’re not in fact articulating two separate consonants, [d d, f f, s s, n n, l l], but just a single prolonged consonant sound: [dː, fː, sː, nː, lː]. This effect is somewhat similar to Italian raddoppiamento. In addition to the doubling indicated in the spelling, Italian also has word-initial doubling, usually termed raddoppiamento (fono)sintattico, triggered by contact with certain ‘doubling’ words, as in a te /at'te/ ‘to you’. This phenomenon shows much regional variation and is in fact absent from most northern accents. If you’re aiming merely at intelligibility, it’s of little significance.

New sounds which the learner needs to master are: (1) the palatal lateral /λ/, as in aglio ‘garlic’ and (2) the palatal nasal / / as in bagno ‘bath(room)’. These sounds can be approached by modifying English /lj/ and /nj/, as in million and onion. Even without modification there should be little problem with intelligibility.

/ as in bagno ‘bath(room)’. These sounds can be approached by modifying English /lj/ and /nj/, as in million and onion. Even without modification there should be little problem with intelligibility.

Italian is rhotic (unlike NRP English) and /r/ is sounded wherever indicated by spelling. Italian /r/ is typically realised as a tap although it is sometimes pronounced as a tongue-tip trill in emphatic speech: raro ['ɾaɾo] ‘rare, infrequent’. Doubling gives rise to pairs like caro ['kaɾo] ‘dear’ and carro ['karo] ‘cart’.

Italian /l/ is invariably clear. You may find that Italians perceive your English dark l as an [u] type back vowel.

Although [ ] isn’t a phoneme in Italian, it functions as an allophone of /n/ in pre-velar contexts, e.g. banca ‘bank’ /banka/ ['ba

] isn’t a phoneme in Italian, it functions as an allophone of /n/ in pre-velar contexts, e.g. banca ‘bank’ /banka/ ['ba ka].

ka].

Unlike English, the Italian voiceless plosives /p t k/ are unaspirated and never glottalised; the voiced plosives /b d g/ have stronger voicing. Italian /t d/ are dental rather than alveolar. When stops are affected by doubling, only the hold stage is lengthened (see p. 90 for a similar effect in English). Italian has four phoneme affricates: /ts dz t∫ ʤ/. Intial z is today usually pronounced as /dz/, although /ts/ is sometimes also to be heard: zucca /'dzukka/ or /'tsukka/ ‘pumpkin’. Medial z can be either /ts/ or /dz/, e.g. razza /'rattsa/ ‘race’ and /'raddza/ ‘ray (sea fish)’. There are no reliable guidelines for such variation. Both /s/ and /z/ occur as phonemes, not dissimilar from their English counterparts; confusingly, both sounds are spelt with the letter s (see below).

Like Spanish, Italian has a simple basic vowel system together with a number of diphthongs. There are seven steady-state vowels in standard Italian /i, e, ε, a, ɔ, o, u/; except for /a/, all the vowels have close to cardinal values. Many regional accents have only five vowels, not distinguishing the mid-vowel pairs: /e/ vs. /ε/ and /o/ vs. /ɔ/. Standard Italian also fluctuates between /e, ε/ and /o, ɔ/, even in the same word: collega, for instance, is in traditional pronunciation /kol'lεga/ when it means ‘colleague’ and /kol'lega/ when it means ‘it connects’, but in fact many Italians today can regularly be heard to say /kol'lεga/ for both. In consequence, the distinction between /e, ε/ and /o, ɔ/ may not be of great importance for the non-native if you are aiming merely at intelligibility.

Unlike English diphthongs, which have a weaker second element, Italian diphthongs show little such effect. English learners should therefore pronounce fully the final element in words such as mai /mai/ ‘never, ever’, poi /pɔi/ ‘then’, voi /voi/ ‘you’ (pl.), dei /dεi/ ‘gods’, dei /dei/ ‘some’, auto /'auto/ ‘car’. Furthermore, the first elements in diphthongs beginning with [i] or [u] are generally said as /j/ and /w/: dieci

/'djεt∫i/ ‘ten’, uomo /'wɔmo/ ‘man’, although in less rapid – or more emphatic – speech, /di'εt∫i/ and /u'cmo/ are also sometimes to be heard.

Unlike NRP English, Italian vowel length is not phonemic and is largely predictable. As a general rule, a vowel is phonetically long when followed by a single consonant which is initial in a following syllable, e.g. mano ['maːno] ‘hand’. In other cases vowels are normally short. Remember the vowel shortening effect of consonant doubling (see above).

The most important errors to tackle are: (1) avoiding diphthongal glides similar to the English vowels FACE /eI/ and GOAT /əƱ/, where Italian has the steady-state vowels /e ε/ and /o ɔ/; and (2) avoiding vowel reduction to [ə] or [I] in unstressed syllables (standard Italian has no central vowels of this type).

Italian spelling is more complex than that of Spanish but nevertheless presents far fewer problems than the orthographic horrors of English or French.

Word-initial letter s may indicate either /s/ as in solo ‘only, alone’ or, if combined with a voiced consonant, /z/, as in sbaglio /'zbaλλo/ ‘mistake’, sguardo /'zgwardo/ ‘look’ (n.), smalto /'zmalto/ ‘enamel’. In other contexts, s may represent either /s/ or /z/: casa /'kaza, -sa/ ‘house, home’. There are no clear guidelines but incorrect usage is unlikely to cause misunderstanding. The letter combination sc is pronounced as /∫/ before e and i, e.g. scendere ‘descend’, and as /sk/ before a, o and u, e.g. scarpa ‘shoe’, scusa ‘excuse’, and when letter h intervenes, e.g. pesche ‘peaches’. Letter z may be either /ts/, as in silenzio /si'lεntsjo/ ‘silence’, or /dz/, as in zero /'dzεro/ ‘zero’. Once again, there are no clear guidelines. Both pronunciations are usually found word-initially as alternatives, e.g. zia /dzia, tsia/ ‘aunt’.

Letter h occurs rarely (mostly in foreign loanwords) and is not pronounced, e.g. hotel /o'tεl/ ‘hotel’. See below for ch and gh.

Before front vowels (e and i), c is pronounced as /t∫/ (similar to English /t∫/), e.g. centrale /t∫en'trale/ ‘central’, circa /'t∫irka/ ‘approximately’. Before open and back vowels (a, o and u), letter c represents /k/, e.g. correre ‘to run’. The letter combination ch represents /k/, e.g. chiuso ‘closed’, while qu is used for /kw/, e.g. quattro ‘four’. Similarly, letter g, when preceding e or i, is pronounced /ʤ/, e.g. gelato ‘ice cream’, but as /g/ before a, o, u, e.g. gamba ‘leg’ and when h intervenes, e.g. spaghetti.

The spelling of Italian vowels is extremely reliable apart from letter e representing both /e/ and /ε/, and letter o both /o/ and /ɔ/. In the case of final stressed vowels, an acute accent is usually employed to indicate /e/, and a grave accent for /ε/, e.g. finché ‘until’, caffè ‘coffee’. However, elsewhere there are no clear guidelines on these mid vowels.

Similarly to Spanish, standard Italian has no clear separation of syllables across word boundaries. Except in emphatic speech, Italian makes frequent use of elision, dropping one of two adjacent identical vowels in phrases such as cinquanta anni [t∫i ,kwan'tanni] ‘fifty years’. This kind of simplification process is also to be found when non-identical vowels are involved, as in otto e trenta [,ɔttet'trεnta] ‘half past eight’.

,kwan'tanni] ‘fifty years’. This kind of simplification process is also to be found when non-identical vowels are involved, as in otto e trenta [,ɔttet'trεnta] ‘half past eight’.

Italian is similar to English in having clearly defined word stress and sentence stress. Words are mostly stressed on the penultimate syllable, but nevertheless a significant number (including many high frequency items) are stressed elsewhere. Final stress is marked with an accent (see above) but unfortunately this is not usually used for earlier stressing.

Stress in longer Italian words is somewhat tricky. Words like salubre ‘healthy’, for instance, tend to fluctuate between stress on the penultimate /sa'lubre/ as opposed to the antepenultimate /'salubre/. Despite being extremely widespread, the antepenultimate pattern is often regarded as ‘incorrect’ by Italian native speakers, including elocutionists and certain linguists.

Unlike English, Italian connected speech has syllable-timed rhythm (see pp. 137– 8), with most syllables having roughly equal duration. In the standard language (as stated above) there is neither reduction of vowels in unstressed syllables to [ə] or [I], nor are there any weak forms (see pp. 21–5). The use of such incorrect English-type vowel reductions in unstressed syllables is a frequent source of error for English-speaking learners of Italian.

However, Italian intonation does show some features similar to English. Notably, there is regularly one obviously prominent lengthened syllable in the intonation group, corresponding to the nucleus. Furthermore, certain Italian intonation tunes bear some similarity to those of English, and may have similar implications.

See Rogers and d’Arcangeli (2004) for more detailed information. Chapallaz (1979) is a very full treatment but somewhat dated.

Audio on Website

Audio on WebsiteGerman has about 90 million native speakers in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Estimates of second-language usage vary widely.

The model usually chosen for non-native learners is educated northern German, as heard on TV and radio. Regional and national varieties of German differ widely, especially in Bavaria, Austria and Switzerland. Swiss German, in its spoken form, is effectively a different language.

Figure C6.8Basic German vowels

Figure C6.9German front rounded vowels

Figure C6.10 German diphthongs

1Some varieties, especially south German, have an additional vowel /εː/ represented by ä, e.g. Käse; compare Beeren – Bären (‘berries’ – ‘bears’), which constitute a minimal pair in these varieties.

2The more open / ə / is the allophone before final /r/. Since most speakers of standard German only sound /r/ before vowels, it is only this more open allophone that provides a contrast in pairs such as: Fische – Fischer ‘fishes’ – ‘fisherman’. It may be represented phonetically as [ ].

].

Like its French counterpart, German /r/ is a back (uvular) approximant. However, unlike French, syllable-final r is normally unsounded. This means that German is effectively non-rhotic, but note that the orthographic final r does have an effect on the length or quality of the preceding vowel. German /l/ is clear in all contexts, and as a result many varieties of English dark l might sound vowel-like to German ears.

Apart from clear l, the velar fricative [x], as in acht ‘eight’, Buch ‘book’, rauchen ‘to smoke’, and the palatal fricative [ç], as in nicht ‘not’, schlecht ‘bad’, durch ‘through’, are the most difficult consonants. Both are spelt ch; they are largely in an allophonic relationship, [ç] occurring after front vowels and also consonants, and [x] elsewhere. Many linguists in fact consider them to be allophones of the same phoneme. Note that non-final orthographic s is pronounced /z/, as in Seite /'zaІtə / ‘page’; orthographic z is an affricate /ts/, e.g. Zeit /'tsaxt/ ‘time’.

Vowel length is important in German, which has a checked/free contrast similar to English. The greatest problems for most students are the front rounded vowels, two long and two short: /yː .Yøː œ/, all indicated in the spelling by an umlaut, e.g. grün ‘green’ /gryːn/, hübsch ‘pretty’ /hYp∫/, schön ‘beautiful’ /∫øːn/, zwölf ‘twelve’ /tsvœlf/. Vowels /eː oː/, e.g. zehn ‘ten’, so ‘so’ are steady-state. The close vowels /iː uː/ (e.g. tief ‘deep’ /tiːf/ and Schuh /∫uː/ ‘shoe’) are peripheral and not diphthongised.

Although not as efficient as that of Spanish, German orthography is much more reliable than that of English or French, with a good correspondence between sound and spelling. It is important to absorb the rules for vowel length; the most significant are perhaps that long vowels are shown with double vowel letters or h, e.g. Saal /zaːl/ ‘hall’, Wahl /vaːl/ ‘choice’, and short vowels are often followed by double consonant letters, e.g. dann /dan/ ‘then’. Even so, there are exceptions.

Unlike Spanish and French, Standard German has clear word separation, and stressed initial vowels are typically preceded by a glottal stop, e.g. einundachtzig ‘eighty-one’ [('?aIn Ʊnt '?axtsIç]. This is totally different from English, where the final consonants tend to be linked to the following word, e.g. an apple [ə næpl]. English students have to avoid using linking and intrusive r, e.g. in aber ich ‘but I’ or meine Absicht ‘my intention’.

This has similarities to English, with each word having an obvious stressed syllable. There is considerable vowel reduction in unstressed syllables to /ə/, generally affecting hographic e, e.g. Bekannte ‘acquaintance’. Rhythm, as in English, is stress-timed, i.e. it is essentially based on intervals between stresses.

Kohler (1999) provides an excellent brief description. More detailed information is to be found in Hall (2003). A reliable German pronunciation dictionary is Duden Aussprachewörterbuch (Mangold 2005).

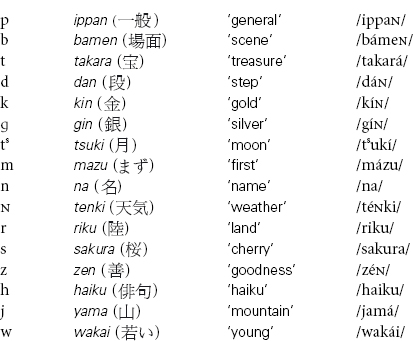

Japanese is spoken by about 120 million native speakers in Japan and by minorities in Hawaii and parts of South America.3 An appropriate model for foreigners is the educated Tokyo accent.

The examples of vowels and consonants below are shown both in the Japanese Hepburn romanisation system and also in kanji characters (see below).

Figure C6.11Basic Japanese vowels

Certain Japanese consonants have counterparts in English, although often with considerable phonetic differences. Other English consonants, namely /f v ө ð r l/, have no such direct counterparts in Japanese.

Before /i/, Japanese /s z/ are realised as [

], e.g. shiika (

], e.g. shiika ( ‘poetry’) /síika/ [

‘poetry’) /síika/ [ iika], aji (

iika], aji ( ; ‘taste’) /azi/ [a

; ‘taste’) /azi/ [a i]. The Japanese /h/ is palatalised before /i/, being realised as a voiceless palatal fricative [ç] as in hikari (

i]. The Japanese /h/ is palatalised before /i/, being realised as a voiceless palatal fricative [ç] as in hikari ( ‘light’) /hikari/ [çikarí]. Before /u/, it is realised as a bilabial fricative [ф], and before the remaining vowels as glottal fricative [h]. However, in the past fifty years or so, it’s become possible to use [ф] before /i a e o/ in addition to /u/. Consequently, for many younger speakers, it’s possible to consider this consonant as an extra independent phoneme /f/.

‘light’) /hikari/ [çikarí]. Before /u/, it is realised as a bilabial fricative [ф], and before the remaining vowels as glottal fricative [h]. However, in the past fifty years or so, it’s become possible to use [ф] before /i a e o/ in addition to /u/. Consequently, for many younger speakers, it’s possible to consider this consonant as an extra independent phoneme /f/.

The realisation of coda /N/ is determined by the place of articulation of the following consonant, i.e. [m] before bilabials, [n] before alveolars and [ ] before velars, e.g. kenmei (

] before velars, e.g. kenmei ( ‘wise’) /kenmei/ [kemmei], tennen (

‘wise’) /kenmei/ [kemmei], tennen ( ‘nature’) /tenneN/ [tenneN], ténki (

‘nature’) /tenneN/ [tenneN], ténki ( ‘weather’) /téNki/ [té

‘weather’) /téNki/ [té ki]). In an open syllable the realisation is as a nasal vowel, e.g. án (

ki]). In an open syllable the realisation is as a nasal vowel, e.g. án ( ‘idea’) /áN/ [áã], ín (

‘idea’) /áN/ [áã], ín ( ‘seal’) /íN/ [

‘seal’) /íN/ [ ], ún (

], ún ( ‘fortune’) /ún/ [úũ].

‘fortune’) /ún/ [úũ].

Japanese has five short vowels: /i e a o u/, as illustrated in the diagram. Japanese /u/ is a close back vowel which can be realised as either unrounded or slightly rounded, and is generally accompanied by lip compression. An unusual feature of Japanese is that the close vowels, /i/ and /u/, are devoiced and often elided when they occur between voiceless consonants, or in unaccented syllable-final position following a voiceless consonant, e.g. kishi ( ‘shore’) /kisí/ [c

‘shore’) /kisí/ [c

i, c

i, c i], kushi (

i], kushi ( ‘comb’) /kusí/ [k

‘comb’) /kusí/ [k

i, k

i, k i].

i].

Japanese has no true diphthongs or long vowels. Native-speaker intuition deter- mines that what may sound like diphthongs and long vowels to English (or non-Japanese) ears are treated phonologically as vowel sequences. A vowel sequence consisting of different vowels will sound somewhat like a diphthong; a double identical vowel sequence sounds like a long vowel.

All vowels can enter into vowel sequences in Japanese. With sequences of different vowels, those with a rising tongue movement similar to a closing diphthong, e.g. saiwai ( ‘happiness’) /saiwai/ [saiwai], are much more frequent than those with a lowering tongue movement similar to opening diphthongs, e.g. shiawase (

‘happiness’) /saiwai/ [saiwai], are much more frequent than those with a lowering tongue movement similar to opening diphthongs, e.g. shiawase ( ‘happiness’) /siawase/ [

‘happiness’) /siawase/ [ iawase]. The double identical vowel sequences are all about equally common, e.g. haaku (

iawase]. The double identical vowel sequences are all about equally common, e.g. haaku ( ‘grasp’) /haaku/ [haaku], ii (

‘grasp’) /haaku/ [haaku], ii ( ‘good’) /íi/ [ii], yuu (

‘good’) /íi/ [ii], yuu ( ‘tie’) /júu, juu/ [júu, juu], keeki (

‘tie’) /júu, juu/ [júu, juu], keeki ( ‘cake’) /kéeki/ [kéeci], Ōsaka (

‘cake’) /kéeki/ [kéeci], Ōsaka ( Osaka (place name)) /oosaka/ [oosaka].

Osaka (place name)) /oosaka/ [oosaka].

Japanese has a simple basic syllable structure of (CC)V(C), i.e. an obligatory vowel with the possibility of up to two consonants in the onset and one consonant in the coda. The second onset consonant is invariably /j/. The coda consonant is either (1) the velar/uvular mora (see below) nasal /N/, or (2) a mora obstruent shown phonologically as /Q/. The mora obstruent is realised by consonant doubling, e.g. ippai ( ) ‘one cup’ /íQpai/ [íppai]/, sakka (

) ‘one cup’ /íQpai/ [íppai]/, sakka ( ) ‘writer’ /saQka, sáQka/ [sakka, sákka].

) ‘writer’ /saQka, sáQka/ [sakka, sákka].

Japanese is notorious for the complicated nature of its writing systems – there are no fewer than four in total! They comprise kanji ( ) (derived from Chinese characters), hiragana (

) (derived from Chinese characters), hiragana ( ), katakana (

), katakana ( ) and romanisation. In the Japanese kanji system, each character can have more than one pronunciation, often with different meanings, which has led to the invention of hiragana and katakana. In both hiragana and katakana each symbol has a fixed pronunciation representing a complete mora (so these systems are syllabic and not alphabetic). Hiragana is used mainly for native Japanese words, whilst katakana is employed for foreign words and loan words.

) and romanisation. In the Japanese kanji system, each character can have more than one pronunciation, often with different meanings, which has led to the invention of hiragana and katakana. In both hiragana and katakana each symbol has a fixed pronunciation representing a complete mora (so these systems are syllabic and not alphabetic). Hiragana is used mainly for native Japanese words, whilst katakana is employed for foreign words and loan words.

Several romanisation alphabets have been devised for Japanese, but nowadays the Hepburn system – which we’ve employed here for the Japanese examples – is the most popular. It uses the familiar letters of the Roman alphabet, representing the mora nasal by a letter n, and the mora obstruent by consonant doubling, e.g. sakka ‘writer’. A long (i.e. doubled) vowel is shown with a macron accent, e.g. Ōsaka ‘Osaka’ (place name).

An important aspect of Japanese phonology is the mora, which relates to the length of a syllable. In brief, the typical Japanese CV syllable (e.g. na) is regarded as a single mora. Syllables containing lengthening elements such as vowel sequences, long vowels, doubled consonants, or coda final /N/ (e.g. mai, yuu, sakka, dan), contain two moras.

Japanese native speakers feel that Japanese rhythm is mora-timed, rather than syllable-timed or stress-timed, so that each mora has approximately the same duration. It becomes apparent when they recite haikus and other verse containing mora nasals, mora obstruents and long vowels. A haiku normally consists of a five-mora st line, a seven-mora second line and a five-mora third line, giving in total 17 moras. Kaki kueba kanega narunari Hōryūji ( ) ‘As I eat a persimmon, I hear the bell tolling from Horyuji temple’ is a haiku by the renowned poet Shiki Masaoka. Hōryūji consists of three syllables but five moras, each long vowel containing two moras. The song that begins with Yūyake koyakeno akatonbo (‘red dragonflies in the red sunset’) is sung ‘yu-u-ya-ke-ko-ya-ke-no-a-ka-to-n-bo’ (

) ‘As I eat a persimmon, I hear the bell tolling from Horyuji temple’ is a haiku by the renowned poet Shiki Masaoka. Hōryūji consists of three syllables but five moras, each long vowel containing two moras. The song that begins with Yūyake koyakeno akatonbo (‘red dragonflies in the red sunset’) is sung ‘yu-u-ya-ke-ko-ya-ke-no-a-ka-to-n-bo’ ( ) (hyphens indicate mora boundaries).

) (hyphens indicate mora boundaries).

Japanese is a pitch-accent language as opposed to the stress accent found in English. Two pitch levels are used in Japanese: high (H) and low (L). Pitch drops sharply from H to L immediately following an accented mora if there is one. In the examples above, an accented mora is shown with an acute accent. Rising or falling intonation can be added at the end of a sentence. For instance, atsui /atsúi/ (‘hot’) can take either a rising intonation /atsúi(↗/ ‘Is it hot?’ or a falling intonation /atsúi↘/ ‘It’s hot’. The pitch contour for the first will be LHLH, and that for the second, LHL. For the first, the final mora will be lengthened to allow an additional H.

A good brief treatment of the Japanese sound system is Okada (1999). For fuller detail, see Vance (2008).

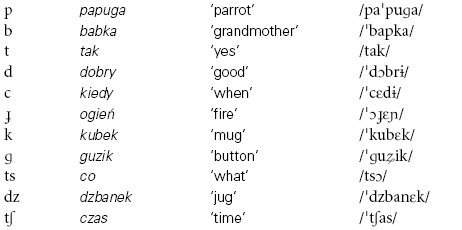

Polish is spoken by almost 40 million Poles in Poland and by perhaps as many as 5 million people of Polish descent elsewhere.4 The standard variety, as described here, is the norm in the media and education.

In pre-velar contexts, [ŋ] functions as an allophone of /n/, e.g. tango ‘tango’ ['taŋgɔ], kaszanka ‘black pudding’ [ka'∫aŋka]). Note that [ŋ] also occurs in words containing the letter ę or ą, e.g. potęga ‘power’ [pɔ'tεŋga], mąka ‘flour’ ['mɔŋka].

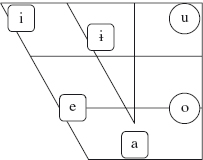

Figure C6.12Basic Polish vowels

The oral vowels can be followed by glides towards [i] or [u]. The final element is normally represented phonemically by /j/ or /w/ respectively, e.g. kij ‘stick’ /kij/, pił ‘he drank’ /piw/, mój ‘my’ /muj/, daj ‘give!’ /daj/, das ‘he gave’ /daw/.

Let’s start with the most complex sounds. Learners from virtually all language backgrounds experience difficulty distinguishing the Polish palato-alveolars /∫Ʒ t∫ ʤ/ and alveolo-palatals /

t

t d

d /. English speakers initially perceive both sets as sounding like the English palato-alveolars /∫ Ʒ t∫ ʤ/. Therefore it’s crucial to realise that in Polish the palato-alveolars and the alveolo-palatals are distinct phonemes. There are countless minimal pairs, e.g. wiesz ‘you know’ /vjε∫/ vs. wieś ‘village’ /vjε

/. English speakers initially perceive both sets as sounding like the English palato-alveolars /∫ Ʒ t∫ ʤ/. Therefore it’s crucial to realise that in Polish the palato-alveolars and the alveolo-palatals are distinct phonemes. There are countless minimal pairs, e.g. wiesz ‘you know’ /vjε∫/ vs. wieś ‘village’ /vjε /, miecz ‘sword’ /mjεt∫/ vs. mieć ‘to have’ /mjεt

/, miecz ‘sword’ /mjεt∫/ vs. mieć ‘to have’ /mjεt /.

/.

For the palato-alveolars /∫Ʒ t∫ ʤ/, start from English [∫Ʒ], maintaining the rounded protruding lip shape (see p. 40). Keep the blade of the tongue close to the alveolar ridge, and the front of the tongue away from the hard palate. The alveolo-palatals /

t

t d

d / can also be formed from the English [∫Ʒ]. Modify the articulation by: (1) unrounding and spreading the lips, and (2) raising the body of the tongue close to the hard palate. Note that the friction of the palato-alveolars is graver than the relatively sharp friction of the alveolo-palatals.

/ can also be formed from the English [∫Ʒ]. Modify the articulation by: (1) unrounding and spreading the lips, and (2) raising the body of the tongue close to the hard palate. Note that the friction of the palato-alveolars is graver than the relatively sharp friction of the alveolo-palatals.

For the palatal plosives /c  /, start from the English sequences /kj/ and /gj/ (as in cute /kjuːt/ and argue /aːgjuː/).The same place of articulation is used for /

/, start from the English sequences /kj/ and /gj/ (as in cute /kjuːt/ and argue /aːgjuː/).The same place of articulation is used for / /. Start from the /nj/ in onion. When articulating any of these palatal sounds, remember to hold the tip of the tongue down behind the lower front teeth. In the flow of speech, Polish /r/ is usually realised as a single tap [r] rather than a trill (see pp. 49–50). Polish /l/ is invariably clear; unlike English, there is no dark l (see p. 74).

/. Start from the /nj/ in onion. When articulating any of these palatal sounds, remember to hold the tip of the tongue down behind the lower front teeth. In the flow of speech, Polish /r/ is usually realised as a single tap [r] rather than a trill (see pp. 49–50). Polish /l/ is invariably clear; unlike English, there is no dark l (see p. 74).

The remaining consonants should cause relatively few problems but remember that, unlike English (see pp. 87–9), the Polish voiceless plosives are unaspirated and never glottalised. Voiced obstruents are fully voiced.

As in German, word-finally all Polish obstruents /b d  g v z Ʒ

g v z Ʒ  dz ʤ d

dz ʤ d / are replaced by their voiceless counterparts /p t c k f s ∫

/ are replaced by their voiceless counterparts /p t c k f s ∫  ts t∫ t

ts t∫ t /. As a result of leading voice assimilation, medial voiced obstruents are devoiced preceding an adjacent voiceless obstruent, e.g. ryba ‘fish’ /'r

/. As a result of leading voice assimilation, medial voiced obstruents are devoiced preceding an adjacent voiceless obstruent, e.g. ryba ‘fish’ /'r ba/ becomes rybka ‘fish (diminutive)’ /'r

ba/ becomes rybka ‘fish (diminutive)’ /'r pka/.

pka/.

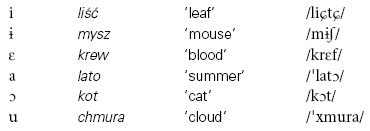

Like Spanish and Italian, Polish has an economical basic vowel system. It consists of six short steady-state vowels (note there are no long vowels). Polish lacks [ə], and English speakers must avoid vowel reduction to [ə] in unstressed syllables. Four Polish vowels /i ε ɔ u/ are very similar to cardinal vowels (see pp. 64–7). English NRP speakers need to use a fully back vowel for /u/, and avoid making /i/ and /u/ either long or diphthongal. A shortened square vowel will serve for Polish /ε/, while Polish /ɔ/ is similar to a short thought vowel. The open central Polish /a/ is about halfway between TRAP and PALM. Polish / / is somewhat more difficult to acquire, being about halfway between [ə] and kit. It is similar to the English allophone of KIT before dark l, as in ill.

/ is somewhat more difficult to acquire, being about halfway between [ə] and kit. It is similar to the English allophone of KIT before dark l, as in ill.

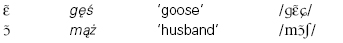

The nasal vowels occur only before fricatives, e.g. rzęsa ‘eyelash’ /'Ʒ sa/, wąż ‘snake’ /v

sa/, wąż ‘snake’ /v ∫/ and, in the case of /

∫/ and, in the case of / /, in word-final position, e.g. są ‘they are’ /s

/, in word-final position, e.g. są ‘they are’ /s /. These vowels have both steady-state [

/. These vowels have both steady-state [ ,

, ] and diphthongal [

] and diphthongal [ ũ,

ũ,  ũ] allophones. The diphthongs are used for the names of the letters ę and ą, and for /

ũ] allophones. The diphthongs are used for the names of the letters ę and ą, and for / / when final; in other contexts usage varies.

/ when final; in other contexts usage varies.

Whilst it may seem somewhat forbidding at first, Polish orthography is actually very consistent. A phoneme can sometimes be represented by different letters (or letter combinations), but any particular letter (or letter combination) can represent only one sound. So there’s no difficulty in working out the pronunciation of an unknown word from its spelling – but it’s not possible to deduce the spelling from a word’s pronunciation. Consequently, quite a few Poles make spelling errors – even with familiar words. (Since non-natives usually begin learning through the written medium, they have no such difficulties.)

The following phonemes are spelt very much as might be expected.

i e a o = vowels /i ε a ɔ/. Note that y represents /

i e a o = vowels /i ε a ɔ/. Note that y represents / /.

/.

p b t d k g = plosives /p b t d k g/

p b t d k g = plosives /p b t d k g/

f s z = fricatives /f s z/

f s z = fricatives /f s z/

m n l r = nasals, lateral and tap r /m n l r/

m n l r = nasals, lateral and tap r /m n l r/

More unexpectedly: w = /v/ whilst ł = /w/; orthographic ki gi c dz cz dż represent the phonemes /c  ts dz t∫ ʤ/. Three phonemes /x Ʒ u/ can be represented by two different spellings:

ts dz t∫ ʤ/. Three phonemes /x Ʒ u/ can be represented by two different spellings:

h or ch = /x/ (e.g. herbata ‘tea’ /xεr'bata/, chata ‘cottage’ /'xata/)

h or ch = /x/ (e.g. herbata ‘tea’ /xεr'bata/, chata ‘cottage’ /'xata/)

ż or rz = /Ʒ/ (e.g. może ‘maybe’ /'mɔƷε/, morze /'mɔƷε / ‘sea’)

ż or rz = /Ʒ/ (e.g. może ‘maybe’ /'mɔƷε/, morze /'mɔƷε / ‘sea’)

u or ó = /u/ (e.g. but ‘shoe’ /but/, ból ‘pain’ /bul/)

u or ó = /u/ (e.g. but ‘shoe’ /but/, ból ‘pain’ /bul/)

Palatal approximant /j/ is generally spelt j, e.g. jak ‘how’ /jak/, klej ‘glue’ /klεj/. But note that it is represented by i after p b f w if preceding a vowel, e.g. pięta ‘heel’ /'pjεnta/, kwiat ‘flower’ /kfjat/. The phonemes /

t

t d

d

/ are written si zi ci dzi ni before a vowel but as ś ź ć dź ń both before a consonant and at the end of a word. The nasal vowels only occur before fricatives; in other contexts, the letters ę and ą represent /ε/ and /ɔ/ plus the nasal consonant that is homorganic with the following stop (e.g. dąb ‘oak’ /dɔmp/, ręce ‘hands’ /'rεntsε/, piękny ‘beautiful’ /'pjε

/ are written si zi ci dzi ni before a vowel but as ś ź ć dź ń both before a consonant and at the end of a word. The nasal vowels only occur before fricatives; in other contexts, the letters ę and ą represent /ε/ and /ɔ/ plus the nasal consonant that is homorganic with the following stop (e.g. dąb ‘oak’ /dɔmp/, ręce ‘hands’ /'rεntsε/, piękny ‘beautiful’ /'pjε kn

kn /). Word-finally, ę represents non-nasal /ε/. Note that the letters q v x are not used in native Polish words.

/). Word-finally, ę represents non-nasal /ε/. Note that the letters q v x are not used in native Polish words.

Polish syllables can have initial and final clusters of up to four consonants, e.g. mnie ‘me’ /m ε/, ssak ‘mammal’ /ssak/, ćma ‘moth’ /t

ε/, ssak ‘mammal’ /ssak/, ćma ‘moth’ /t ma/, krtań ‘larynx’ /krta

ma/, krtań ‘larynx’ /krta /, mgła ‘fog’ /mgwa/, źdźbło ‘blade of grass’ /

/, mgła ‘fog’ /mgwa/, źdźbło ‘blade of grass’ / d

d bwɔ/, pstrąg ‘trout’ /pstrɔ

bwɔ/, pstrąg ‘trout’ /pstrɔ k/, warstw ‘layers (gen.)’ /varstf/. Many of these clusters are unfamiliar to English speakers and difficult to combine.

k/, warstw ‘layers (gen.)’ /varstf/. Many of these clusters are unfamiliar to English speakers and difficult to combine.

In contrast with English, where an epenthetic plosive may be inserted in nasal-fricative consonant sequences (see p. 124), in Polish the nasal consonant is elided and the preceding vowel is nasalised e.g. kunszt ‘craftmanship’ [kũ∫t], szansa ‘chance’ ['∫ãsa].

Polish word stress (with few exceptions), falls on the penultimate syllable, as can be seen from the examples already cited. The Polish preference for penultimate stress is also evident from the pronunciation of certain constructions where stress falls on the first of two monosyllabic words. This occurs:

when the word nie ‘not’ /

when the word nie ‘not’ / ε/ is used with a verb of one syllable (e.g. nie wiem ‘I do not know’ /

ε/ is used with a verb of one syllable (e.g. nie wiem ‘I do not know’ / ε vjεm/, nie masz ‘you do not have’ /

ε vjεm/, nie masz ‘you do not have’ / ε ma∫/);

ε ma∫/);

when a monosyllabic preposition is used with a monosyllabic pronoun (e.g. do niej ‘to her’ /'dɔ

when a monosyllabic preposition is used with a monosyllabic pronoun (e.g. do niej ‘to her’ /'dɔ  εj/, o tym ‘about it’ /'c t

εj/, o tym ‘about it’ /'c t m/, o czym? ‘about what?’ /'ɔt∫

m/, o czym? ‘about what?’ /'ɔt∫ m/);

m/);

in certain frequently used phrases (e.g. na czczo ‘on an empty stomach’ /'na t∫t∫ɔ/, na wsi ‘in the country’ /'na f

in certain frequently used phrases (e.g. na czczo ‘on an empty stomach’ /'na t∫t∫ɔ/, na wsi ‘in the country’ /'na f i/, na dół ‘downstairs’ /'na duw/).

i/, na dół ‘downstairs’ /'na duw/).

Although there is some controversy over whether Polish can truly be considered a syllable-timed language, its rhythm is clearly very different from the obvious stress-timing of English. Unlike English (see p. 129), Polish vowels in unstressed syllables have little variation in length (they’re always short), little obvious centralisation, and no reduction to [ə].

Jassem (2003) provides an authoritative brief description of the Polish sound system.

1 Thanks to Masaki Taniguchi for much help with this section.

2 This section on Italian has been co-written with Alessandro Rotatori of the Università degli Studi della Tuscia, Viterbo, Italy. Our thanks go to him for sharing with us the benefit of his phonetic expertise and native-speaker knowledge of Italian.

3 This section on Japanese and that on Japanese learners’ errors on pp. 218–19 have been co-written with Professor Masaki Taniguchi of Kochi University, Japan. Our thanks go to him for sharing with us the benefit of his phonetic expertise and his native-speaker knowledge of Japanese.

4 This section on Polish has been co-written with Paul Carley. We wish to express our thanks to him for allowing us to benefit from his phonetic expertise and extensive knowledge of Polish.